28 Chapter 28: Memory

Phyllis Nissila and Dave Dillon

“If I had eight hours to chop down a tree, I’d spend six hours sharpening my ax.”

– Abraham Lincoln

An Information Processing Model

Once information has been encoded, we have to retain it. Our brains take the encoded information and place it in storage. Storage is the creation of a permanent record of information.

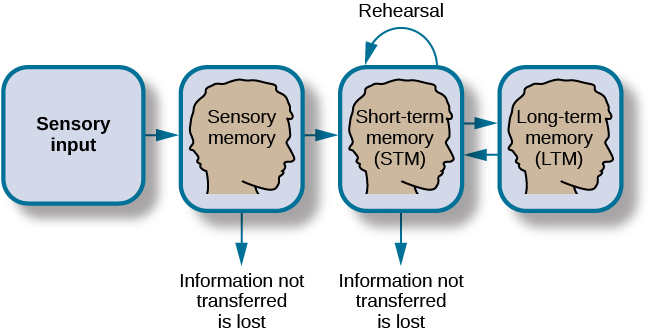

In order for a memory to go into storage (i.e., long-term memory), it has to pass through three distinct stages: Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and finally Long-Term Memory. These stages were first proposed by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968). Their model of human memory is based on the belief that we process memories in the same way that a computer processes information.

Learning, Remembering, and Retrieving Information Is Important for Academic Success

The first thing our brains do is to take in information from our senses (what we see, hear, taste, touch and smell). In many classroom and homework settings, we primarily use hearing for lectures and seeing for reading textbooks. Information we perceive from our senses is stored in what we call the short-term memory.

It is useful to then be able to do multiple things with information in the short-term memory. We want to: 1) decide if that information is important; 2) for the information that is important, be able to save the information in our brain on a longer-term basis—this storage is called the long-term memory; 3) retrieve that information when we need to. Exams often measure how effectively the student can retrieve “important information.”

In some classes and with some textbooks it is easy to determine information important to memorize. In other courses with other textbooks, that process may be more difficult. Your instructor can be a valuable resource to assist with determining the information that needs to be memorized. Once the important information is identified, it is helpful to organize it in a way that will help you best understand.

Author’s Story

I do not have a great memory. I write a lot of things down to help me remember. And I have always had to work hard to memorize and study for exams.

In my high school and college years I spent a lot of time cramming the night before the exam. In retrospect, I believe this was partly due to procrastination, partly due to lack of interest in the material, and partly—subconsciously—wanting to perform well on the exam without putting a lot of time into preparation (an attempt to get the maximum of the minimum). Cramming allowed me to store a lot of information in my short-term memory. I would regurgitate information on the exam and then forget nearly all of it shortly thereafter. It is not how learning and education were intended.

My performance on the exams were satisfactory, but I could’ve done much better had I adequately prepared and been disciplined enough to review more frequently. Doing so would have allowed much of that information to enter my long-term memory, which would have had many benefits. Students often believe the information they are learning in classes that are required for general education have little to do with what is needed for them in their future career. However, skills like critical thinking, communication (both oral and written), and literacy are often developed from these courses and are extremely beneficial for the student. Sometimes these skills are acquired without the student realizing it! This makes for a better student, better person and better member of society.

In addition, I would love to be able to recall information from some classes I took in high school and college, but cannot because the information never entered my long-term memory. I did some of it the wrong way and hope that you do not make the same mistake. Students who take in information by gradually reviewing and memorizing over a longer period of time and can store more information in their long-term memory will be able to access it long after the course they are taking is over.

Moving Information from the Short-term Memory To the Long-term Memory

This is something that takes a lot of time: there is no shortcut for it. Students who skip putting in the time and work often end up cramming at the end.

Preview the information you are trying to memorize. The more familiar you are with what you are learning, the better. Create acronyms like SCUBA for memorizing “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus.” Organizing information in this way can be helpful because it is not as difficult to memorize the acronym, and with practice and repetition, the acronym can trigger the brain to recall the entire piece of information.

Flash cards are a valuable tool for memorization because they allow students to be able to test themselves. They are convenient to bring with you anywhere, and can be used effectively whether a student has one minute or an hour.

Once information is memorized, regardless of when the exam is, the last step is to apply the information. Ask yourself: In what real world scenarios could you apply this information? And for mastery, try to teach the information to someone else.

Licenses and Attributions:

CC licensed content, previously shared:

Nissila, Phyllis. How to Learn Like a Pro! Open Oregon Educational Resources, 2016. Located at: https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/collegereading/chapter/lesson-5-1-memory-model-and-principles/ CC-BY: Attribution.

Adaptions: Changed formatting, removed image, removed pre-test link, removed exercises.

“How memory functions” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Content previously copyrighted, published in Blueprint for Success in College: Indispensable Study Skills and Time Management Strategies (by Dave Dillon), now licensed as CC BY Attribution.