7.3 Approaching Interpersonal Conflict

Learning Objectives

- Define interpersonal conflict.

- Compare and contrast the five styles of interpersonal conflict management.

- Explain how perception and culture influence interpersonal conflict.

- List strategies for effectively managing conflict.

Conflict and Interpersonal Communication

Who do you have the most conflict with right now? Your answer to this question probably depends on the various contexts in your life. If you still live at home with a parent or parents, you may have daily conflicts with your family as you try to balance your autonomy, or desire for independence, with the practicalities of living under your family’s roof. If you’ve recently moved away to go to college, you may be negotiating roommate conflicts as you adjust to living with someone you may not know at all. You probably also have experiences managing conflict in romantic relationships and in the workplace. So think back and ask yourself, “How well do I handle conflict?” As with all areas of communication, we can improve if we have the background knowledge to identify relevant communication phenomena and the motivation to reflect on and enhance our communication skills.

Interpersonal conflict occurs in interactions where there are real or perceived incompatible goals, scarce resources, or opposing viewpoints. Interpersonal conflict may be expressed verbally or nonverbally along a continuum ranging from a nearly imperceptible cold shoulder to a very obvious blowout.

Conflict is an inevitable part of close relationships and can take a negative emotional toll. It takes effort to ignore someone or be passive-aggressive, and the anger or guilt we may feel after blowing up at someone are valid negative feelings. However, conflict isn’t always negative or unproductive. In fact, numerous research studies have shown that the quantity of conflict in a relationship is not as important as how the conflict is handled (Markman et al., 1993). Additionally, when conflict is well managed, it has the potential to lead to more rewarding and satisfactory relationships (Canary & Messman, 2000).

Improving your competence in dealing with conflict can yield positive effects in the real world. Since conflict is present in our personal and professional lives, the ability to manage conflict and negotiate desirable outcomes can help us be more successful at both. Whether you and your partner are trying to decide what brand of flat-screen television to buy or discussing the upcoming political election with your mother, the potential for conflict is present. In professional settings, the ability to engage in conflict management, sometimes called conflict resolution, is a necessary and valued skill. However, many professionals do not receive training in conflict management even though they are expected to do it as part of their job (Gates, 2006).

A lack of training and a lack of competence could be a recipe for disaster, which is illustrated in an episode of The Office titled “Conflict Resolution.” In the episode, Toby, the human resources officer, encourages office employees to submit anonymous complaints about their coworkers. Although Toby doesn’t attempt to resolve the conflicts, the employees feel like they are being heard. When Michael, the manager, finds out there is unresolved conflict, he makes the anonymous complaints public in an attempt to encourage resolution, which backfires, creating more conflict within the office. As usual, Michael doesn’t demonstrate communication competence; however, there are career paths for people who do have an interest in or talent for conflict management. In fact, being a mediator was named one of the best careers for 2011 by U.S. News and World Report. Many colleges and universities now offer undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees, or certificates in conflict resolution, such as this one at the University of North Carolina Greensboro: http://conflictstudies.uncg.edu/site. Being able to manage conflict situations can make life more pleasant rather than letting a situation stagnate or escalate. The negative effects of poorly handled conflict could range from an awkward last few weeks of the semester with a college roommate to violence or divorce. However, there is no absolute right or wrong way to handle a conflict. Remember that being a competent communicator doesn’t mean that you follow a set of absolute rules. Rather, a competent communicator assesses multiple contexts and applies or adapts communication tools and skills to fit the dynamic situation.

Conflict Management Styles

Would you describe yourself as someone who prefers to avoid conflict? Do you like to get your way? Are you good at working with someone to reach a solution that is mutually beneficial? Odds are that you have been in situations where you could answer yes to each of these questions, which underscores the important role context plays in conflict and conflict management styles in particular. The way we view and deal with conflict is learned and contextual. Is the way you handle conflicts similar to the way your parents handle conflict? If you’re of a certain age, you are likely predisposed to answer this question with a certain “No!” It wasn’t until my late twenties and early thirties that I began to see how similar I am to my parents, even though I, like many, spent years trying to distinguish myself from them. Research does show that there is intergenerational transmission of traits related to conflict management. As children, we test out different conflict resolution styles we observe in our families with our parents and siblings. Later, as we enter adolescence and begin developing platonic and romantic relationships outside the family, we begin testing what we’ve learned from our parents in other settings. If a child has observed and used negative conflict management styles with siblings or parents, he or she is likely to exhibit those behaviors with non–family members (Reese-Weber & Bartle-Haring, 1998).

There has been much research done on different types of conflict management styles, which are communication strategies that attempt to avoid, address, or resolve a conflict. Keep in mind that we don’t always consciously choose a style. We may instead be caught up in emotion and become reactionary. The strategies for more effectively managing conflict that will be discussed later may allow you to slow down the reaction process, become more aware of it, and intervene in the process to improve your communication.

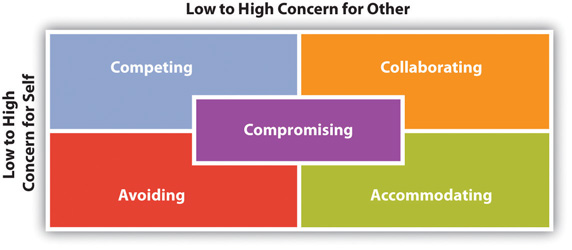

A powerful tool to mitigate conflict is information exchange. Asking for more information before you react to a conflict-triggering event is a good way to add a buffer between the trigger and your reaction. Another key element is whether or not a communicator is oriented toward self-centered or other-centered goals. For example, if your goal is to “win” or make the other person “lose,” you show a high concern for self and a low concern for other. If your goal is to facilitate a “win/win” resolution or outcome, you show a high concern for self and other. In general, strategies that facilitate information exchange and include concern for mutual goals will be more successful at managing conflict (Sillars, 1980). The five strategies for managing conflict we will discuss are competing, avoiding, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. Each of these conflict styles accounts for the concern we place on self versus other.

In order to better understand the elements of the five styles of conflict management, we will apply each to the following scenario. Rosa and D’Shaun have been partners for seventeen years. Rosa is growing frustrated because D’Shaun continues to give money to their teenage daughter, Casey, even though they decided to keep the teen on a fixed allowance to try to teach her more responsibility. While conflicts regarding money and child-rearing are very common, we will see the numerous ways that Rosa and D’Shaun could address this problem.

Competing

The competing style indicates a high concern for self and a low concern for other. When we compete, we are striving to “win” the conflict, potentially at the expense or “loss” of the other person. One way we may gauge our win is by being granted or taking concessions from the other person. For example, if D’Shaun gives Casey extra money behind Rosa’s back, he is taking an indirect competitive route resulting in a “win” for him because he got his way. The competing style also involves the use of power, which can be noncoercive or coercive (Sillars, 1980). Noncoercive strategies include requesting and persuading. When requesting, we suggest the conflict partner change a behavior. Requesting doesn’t require a high level of information exchange. When we persuade, however, we give our conflict partner reasons to support our request or suggestion, meaning there is more information exchange, which may make persuading more effective than requesting. Rosa could try to persuade D’Shaun to stop giving Casey extra allowance money by bringing up their fixed budget or reminding him that they are saving for a summer vacation. Coercive strategies violate standard guidelines for ethical communication and may include aggressive communication directed at rousing your partner’s emotions through insults, profanity, and yelling, or through threats of punishment if you do not get your way. If Rosa is the primary income earner in the family, she could use that power to threaten to take D’Shaun’s ATM card away if he continues giving Casey money. In all these scenarios, the “win” that could result is only short-term and can lead to conflict escalation. Interpersonal conflict is rarely isolated, meaning there can be ripple effects that connect the current conflict to previous and future conflicts. D’Shaun’s behind-the-scenes money giving or Rosa’s confiscation of the ATM card could lead to built-up negative emotions that could further test their relationship.

Competing has been linked to aggression, although the two are not always paired. If assertiveness does not work, there is a chance it could escalate to hostility. There is a pattern of verbal escalation: requests, demands, complaints, angry statements, threats, harassment, and verbal abuse (Johnson & Roloff, 2000). Aggressive communication can become patterned, which can create a volatile and hostile environment. The reality television show The Bad Girls Club is a prime example of a chronically hostile and aggressive environment. If you do a Google video search for clips from the show, you will see yelling, screaming, verbal threats, and some examples of physical violence. The producers of the show choose houseguests who have histories of aggression, and when the “bad girls” are placed in a house together, they fall into typical patterns, which creates dramatic television moments. Obviously, living in this type of volatile environment would create stressors in any relationship, so it’s important to monitor the use of competing as a conflict resolution strategy to ensure that it does not lapse into aggression.

The competing style of conflict management is not the same thing as having a competitive personality. Competition in relationships isn’t always negative, and people who enjoy engaging in competition may not always do so at the expense of another person’s goals. In fact, research has shown that some couples engage in competitive shared activities like sports or games to maintain and enrich their relationship (Dindia & Baxter, 1987). And although we may think that competitiveness is gendered, research has often shown that women are just as competitive as men (Messman & Mikesell, 2000).

Avoiding

The avoiding style of conflict management often indicates a low concern for self and a low concern for other, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. However, as we will discuss later, in some cultures that emphasize group harmony over individual interests, and even in some situations in the United States, avoiding a conflict can indicate a high level of concern for the other. In general, avoiding doesn’t mean that there is no communication about the conflict. Remember, you cannot not communicate. Even when we try to avoid conflict, we may intentionally or unintentionally give our feelings away through our verbal and nonverbal communication. Rosa’s sarcastic tone as she tells D’Shaun that he’s “Soooo good with money!” and his subsequent eye-roll both bring the conflict to the surface without specifically addressing it. The avoiding style is either passive or indirect, meaning there is little information exchange, which may make this strategy less effective than others. We may decide to avoid conflict for many different reasons, some of which are better than others. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive a conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it and hope that it will solve itself. If you are not emotionally invested in the conflict, you may be able to reframe your perspective and see the situation in a different way, therefore resolving the issue. In all these cases, avoiding doesn’t really require an investment of time, emotion, or communication skill, so there is not much at stake to lose.

Avoidance is not always an easy conflict management choice, because sometimes the person we have a conflict with isn’t a temp in our office or a weekend houseguest. While it may be easy to tolerate a problem when you’re not personally invested in it or view it as temporary, when faced with a situation like Rosa and D’Shaun’s, avoidance would just make the problem worse. For example, avoidance could first manifest as changing the subject, then progress from avoiding the issue to avoiding the person altogether, to even ending the relationship.

Indirect strategies of hinting and joking also fall under the avoiding style. While these indirect avoidance strategies may lead to a buildup of frustration or even anger, they allow us to vent a little of our built-up steam and may make a conflict situation more bearable. When we hint, we drop clues that we hope our partner will find and piece together to see the problem and hopefully change, thereby solving the problem without any direct communication. In almost all the cases of hinting that I have experienced or heard about, the person dropping the hints overestimates their partner’s detective abilities. For example, when Rosa leaves the bank statement on the kitchen table in hopes that D’Shaun will realize how much extra money he is giving Casey, D’Shaun may simply ignore it or even get irritated with Rosa for not putting the statement with all the other mail. We also overestimate our partner’s ability to decode the jokes we make about a conflict situation. It is more likely that the receiver of the jokes will think you’re genuinely trying to be funny or feel provoked or insulted than realize the conflict situation that you are referencing. So more frustration may develop when the hints and jokes are not decoded, which often leads to a more extreme form of hinting/joking: passive-aggressive behavior.

Passive-aggressive behavior is a way of dealing with conflict in which one person indirectly communicates their negative thoughts or feelings through nonverbal behaviors, such as not completing a task. For example, Rosa may wait a few days to deposit money into the bank so D’Shaun can’t withdraw it to give to Casey, or D’Shaun may cancel plans for a romantic dinner because he feels like Rosa is questioning his responsibility with money. Although passive-aggressive behavior can feel rewarding in the moment, it is one of the most unproductive ways to deal with conflict. These behaviors may create additional conflicts and may lead to a cycle of passive-aggressiveness in which the other partner begins to exhibit these behaviors as well, while never actually addressing the conflict that originated the behavior. In most avoidance situations, both parties lose. However, as noted above, avoidance can be the most appropriate strategy in some situations—for example, when the conflict is temporary when the stakes are low or there is little personal investment, or when there is the potential for violence or retaliation.

Accommodating

The accommodating conflict management style indicates a low concern for self and a high concern for other and is often viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. Generally, we accommodate because we are being generous, we are obeying, or we are yielding (Bobot, 2010). If we are being generous, we accommodate because we genuinely want to; if we are obeying, we don’t have a choice but to accommodate (perhaps due to the potential for negative consequences or punishment); and if we yield, we may have our own views or goals but give up on them due to fatigue, time constraints, or because a better solution has been offered. Accommodating can be appropriate when there is little chance that our own goals can be achieved when we don’t have much to lose by accommodating when we feel we are wrong, or when advocating for our own needs could negatively affect the relationship (Isenhart & Spangle, 2000). The occasional accommodation can be useful in maintaining a relationship—remember earlier we discussed putting another’s needs before your own as a way to achieve relational goals. For example, Rosa may say, “It’s OK that you gave Casey some extra money; she did have to spend more on gas this week since the prices went up.” However, being a team player can slip into being a pushover, which people generally do not appreciate. If Rosa keeps telling D’Shaun, “It’s OK this time,” they may find themselves short on spending money at the end of the month. At that point, Rosa and D’Shaun’s conflict may escalate as they question each other’s motives, or the conflict may spread if they direct their frustration at Casey and blame it on her irresponsibility.

Research has shown that the accommodating style is more likely to occur when there are time restraints and less likely to occur when someone does not want to appear weak (Cai & Fink, 2002). If you’re standing outside the movie theatre and two movies are starting, you may say, “Let’s just have it your way,” so you don’t miss the beginning. If you’re a new manager at an electronics store and an employee wants to take Sunday off to watch a football game, you may say no to set an example for the other employees. As with avoiding, there are certain cultural influences we will discuss later that make accommodating a more effective strategy.

Compromising

The compromising style shows a moderate concern for self and other and may indicate that there is a low investment in the conflict and/or the relationship. Even though we often hear that the best way to handle a conflict is to compromise, the compromising style isn’t a win/win solution; it is a partial win/lose. In essence, when we compromise, we give up some or most of what we want. It’s true that the conflict gets resolved temporarily, but lingering thoughts of what you gave up could lead to a future conflict. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked (Macintosh & Stevens, 2008).

Compromise is sometimes viewed as meeting in the middle. Compromise - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

A negative of compromising is that it may be used as an easy way out of a conflict. The compromising style is most effective when both parties find the solution agreeable. Rosa and D’Shaun could decide that Casey’s allowance does need to be increased and could each give ten more dollars a week by committing to taking their lunch to work twice a week instead of eating out. They are both giving up something, and if neither of them have a problem with taking their lunch to work, then the compromise was equitable. If the couple agrees that the twenty extra dollars a week should come out of D’Shaun’s golf budget, the compromise isn’t as equitable, and D’Shaun, although he agreed to the compromise, may end up with feelings of resentment. Wouldn’t it be better to both win?

Collaborating

The collaborating style involves a high degree of concern for self and other and usually indicates investment in the conflict situation and the relationship. Although the collaborating style takes the most work in terms of communication competence, it ultimately leads to a win/win situation in which neither party has to make concessions because a mutually beneficial solution is discovered or created. The obvious advantage is that both parties are satisfied, which could lead to positive problem-solving in the future and strengthen the overall relationship. For example, Rosa and D’Shaun may agree that Casey’s allowance needs to be increased and may decide to give her twenty more dollars a week in exchange for her babysitting her little brother one night a week. In this case, they didn’t make the conflict personal but focused on the situation and came up with a solution that may end up saving them money. The disadvantage is that this style is often time-consuming, and only one person may be willing to use this approach while the other person is eager to compete to meet their goals or willing to accommodate.

Here are some tips for collaborating and achieving a win/win outcome (Hargie, 2011):

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Remain flexible and realize there are solutions yet to be discovered.

- Distinguish the people from the problem (don’t make it personal).

- Determine what the underlying needs are that are driving the other person’s demands (needs can still be met through different demands).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions to allow them to clarify and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

“Getting Competent”

Handling Roommate Conflicts

Whether you have a roommate by choice, by necessity, or through the random selection process of your school’s housing office, it’s important to be able to get along with the person who shares your living space. While having a roommate offers many benefits such as making a new friend, having someone to experience a new situation like college life with, and having someone to split the cost on your own with, there are also challenges. Some common roommate conflicts involve neatness, noise, having guests, sharing possessions, value conflicts, money conflicts, and personality conflicts (Ball State University, 2001). Read the following scenarios and answer the following questions for each one:

- Which conflict management style, from the five discussed, would you use in this situation?

- What are the potential strengths of using this style?

- What are the potential weaknesses of using this style?

Scenario 1: Neatness. Your college dorm has bunk beds, and your roommate takes a lot of time making his bed (the bottom bunk) each morning. He has told you that he doesn’t want anyone sitting on or sleeping in his bed when he is not in the room. While he is away for the weekend, your friend comes to visit and sits on the bottom bunk bed. You tell him what your roommate said, and you try to fix the bed back before he returns to the dorm. When he returns, he notices that his bed has been disturbed and he confronts you about it.

Scenario 2: Noise and having guests. Your roommate has a job waiting tables and gets home around midnight on Thursday nights. She often brings a couple friends from work home with her. They watch television, listen to music, or play video games and talk and laugh. You have an 8 a.m. class on Friday mornings and are usually asleep when she returns. Last Friday, you talked to her and asked her to keep it down in the future. Tonight, their noise has woken you up and you can’t get back to sleep.

Scenario 3: Sharing possessions. When you go out to eat, you often bring back leftovers to have for lunch the next day during your short break between classes. You didn’t have time to eat breakfast, and you’re really excited about having your leftover pizza for lunch until you get home and see your roommate sitting on the couch eating the last slice.

Scenario 4: Money conflicts. Your roommate got mono and missed two weeks of work last month. Since he has a steady job and you have some savings, you cover his portion of the rent and agree that he will pay your portion next month. The next month comes around and he informs you that he only has enough to pay his half.

Scenario 5: Value and personality conflicts. You like to go out to clubs and parties and have friends over, but your roommate is much more of an introvert. You’ve tried to get her to come out with you or join the party at your place, but she’d rather study. One day she tells you that she wants to break the lease so she can move out early to live with one of her friends. You both signed the lease, so you have to agree or she can’t do it. If you break the lease, you automatically lose your portion of the security deposit.

Common Conflict Behaviors

Apologies/concessions

Most common of the remedial strategies, an apology is the most straightforward means by which to admit responsibility, express regret, and seek forgiveness. Noted earlier, apologies are most effective if provided in a timely manner and involve a self-disclosure. Apologies occurring after the discovery of a transgression by a third party are much less effective. Though apologies can range from a simple, “I’m sorry” to more elaborate forms, offenders are most successful when offering more complex apologies to match the seriousness of the transgression.

Excuses/justifications

Rather than accepting responsibility for a transgression through the form of an apology, a transgressor who explains why they engaged in behavior is engaging in excuses or justifications. While excuses and justifications aim to minimize blame on the transgressor, the two address blame minimization from completely opposite perspectives. Excuses attempt to minimize blame by focusing on a transgressor’s inability to control their actions (e.g., “How would I have known my ex-girlfriend was going to be at the party.”) or displace blame on a third party (e.g., “I went to lunch with my ex-girlfriend because I did not want to hurt her feelings.”). Conversely, a justification minimizes blame by suggesting that actions surrounding the transgression were justified or that the transgression was not severe. For example, a transgressor may justify having lunch with a past romantic interest, suggesting to their current partner that the lunch meeting was of no major consequence (e.g., “We are just friends.”).

Refusals

Refusals are where a transgressor claims no blame for the perceived transgression. This is a departure from apologies and excuses/justifications which involve varying degrees of blame acceptance. In the case of a refusal, the transgressor believes that they have not done anything wrong. Such a situation points out the complexity of relational transgressions. The perceptions of both partners must be taken into account when recognizing and addressing transgressions. For example, Bob and Sally have just started to date, but have not addressed whether they are mutually exclusive. When Bob finds out that Sally has been on a date with someone else, he confronts Sally. Sally may engage in refusal of blame because Bob and Sally had not explicitly noted whether they were mutually exclusive. The problem with these situations is that the transgressor shows no sensitivity to the offended. As such, the offended is less apt to exhibit empathy which is key towards forgiveness. As such, research has shown that refusals tend to aggravate situations, rather than serve as a meaningful repair strategy.

Appeasement/positivity

Appeasement is used to offset hurtful behavior through the transgressor ingratiating themselves in ways such as promising never to commit the hurtful act or being overly kind to their partner. Appeasement may elicit greater empathy from the offended, through soothing strategies exhibited by the transgressor (e.g., complimenting, being more attentive, spending greater time together). However, the danger of appeasement is the risk that the actions of transgressors will be viewed as being artificial. For example, sending your partner flowers every day resulting from an infidelity you have committed, may be viewed as downplaying the severity of the transgression if the sending of flowers is not coupled with other soothing strategies that cause greater immediacy.

Avoidance/evasion

Avoidance involves the transgressor making conscious efforts to ignore the transgression (also referred to as “silence”). Avoidance can be effective after an apology is sought and forgiveness is granted (i.e., minimizing discussion around unpleasant subjects once closure has been obtained). However, total avoidance of a transgression where the hurt of the offended is not recognized and forgiveness is not granted can result in further problems in the future. As relational transgressions tend to develop the nature of the relationship through drawing of new rules/boundaries, avoidance of a transgression does not allow for this development. Not surprisingly, avoidance is ineffective as a repair strategy, particularly for instances in which infidelity has occurred.

Relationship talk

Relationship talk is a remediation strategy that focuses on discussing transgression in the context of the relationship. Aune et al. (1998) identified two types of relationship talk, relationship invocation and metatalk. Relationship invocation involves using the relationship as a backdrop for a discussion of the transgression. For example, “We are too committed to this relationship to let it fail.”, or “Our relationship is so much better than any of my previous relationships.” Metatalk involves discussing the effect of the transgression on the relationship. For example, infidelity may cause partners to redefine rules of the relationship and reexamine the expectations of commitment each partner expects from the other.

Gunnysacking

George Bach and Peter Wyden discuss gunnysacking (or backpacking) as the imaginary bag we all carry into which we place unresolved conflicts or grievances over time. Holding onto the way things used to be can be like a stone in your gunnysack, and influence how you interpret your current context. Gunnysacking may be expressed by bringing up previous behaviors the other has engaged in or previous arguments you felt were unresolved.

Bottling up your frustrations only hurts you and can cause your current relationships to suffer. By addressing, or unpacking, the stones you carry, you can better assess the current situation with the current patterns and variables. We learn from experience but can distinguish between old wounds and current challenges, and try to focus our energies where they will make the most positive impact.

Culture and Conflict

Culture is an important context to consider when studying conflict, and recent research has called into question some of the assumptions of the five conflict management styles discussed so far, which were formulated with a Western bias (Oetzel, Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008). For example, while the avoiding style of conflict has been cast as negative, with a low concern for self and other or as a lose/lose outcome, this research found that participants in the United States, Germany, China, and Japan all viewed avoiding strategies as demonstrating a concern for the other. While there are some generalizations we can make about culture and conflict, it is better to look at more specific patterns of how interpersonal communication and conflict management are related. We can better understand some of the cultural differences in conflict management by further examining the concept of face.

What does it mean to “save face?” This saying generally refers to preventing embarrassment or preserving our reputation or image, which is similar to the concept of face in interpersonal and intercultural communication. You may remember that our face is a reflection of the self that we desire to put into the world, and facework refers to the communicative strategies we employ to project, maintain, or repair our face or maintain, repair, or challenge another’s face. Face negotiation theory argues that people in all cultures negotiate face through communication encounters and that cultural factors influence how we engage in facework, especially in conflict situations (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). These cultural factors influence whether we are more concerned with self-face or other-face and what types of conflict management strategies we may use. One key cultural influence on face negotiation is the distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures.

The distinction between individualistic and collectivistic cultures is an important dimension across which all cultures vary. Individualistic cultures like the United States and most of Europe emphasize individual identity over group identity and encourage competition and self-reliance. Collectivistic cultures like Taiwan, Colombia, China, Japan, Vietnam, and Peru value in-group identity over individual identity and value conformity to social norms of the in-group (Dsilva & Whyte, 1998). However, within the larger cultures, individuals will vary in the degree to which they view themselves as part of a group or as a separate individual, which is called self-construal. Independent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as an individual with unique feelings, thoughts, and motivations. Interdependent self-construal indicates a perception of the self as interrelated with others (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). Not surprisingly, people from individualistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of independent self-construal, and people from collectivistic cultures are more likely to have higher levels of interdependent self-construal. Self-construal and individualistic or collectivistic cultural orientations affect how people engage in facework and the conflict management styles they employ.

Self-construal alone does not have a direct effect on conflict style, but it does affect face concerns, with independent self-construal favoring self-face concerns and interdependent self-construal favoring other-face concerns. There are specific facework strategies for different conflict management styles, and these strategies correspond to self-face concerns or other-face concerns.

- Accommodating. Giving in (self-face concern).

- Avoiding. Pretending conflict does not exist (other-face concern).

- Competing. Defending your position, persuading (self-face concern).

- Collaborating. Apologizing, having a private discussion, and remaining calm (other-face concern) (Oetzel, Garcia, & Ting-Toomey, 2008).

Research done on college students in Germany, Japan, China, and the United States found that those with independent self-construal were more likely to engage in competing, and those with interdependent self-construal were more likely to engage in avoiding or collaborating (Oetzel & Ting-Toomey, 2003). And in general, this research found that members of collectivistic cultures were more likely to use the avoiding style of conflict management and less likely to use the integrating or competing styles of conflict management than were members of individualistic cultures. The following examples bring together facework strategies, cultural orientations, and conflict management style: Someone from an individualistic culture may be more likely to engage in competing as a conflict management strategy if they are directly confronted, which may be an attempt to defend their reputation (self-face concern). Someone in a collectivistic culture may be more likely to engage in avoiding or accommodating in order not to embarrass or anger the person confronting them (other-face concern) or out of concern that their reaction could reflect negatively on their family or cultural group (other-face concern). While these distinctions are useful for categorizing large-scale cultural patterns, it is important not to essentialize or arbitrarily group countries together, because there are measurable differences within cultures. For example, expressing one’s emotions was seen as demonstrating a low concern for other-face in Japan, but this was not so in China, which shows there is variety between similarly collectivistic cultures. Culture always adds layers of complexity to any communication phenomenon, but experiencing and learning from other cultures also enriches our lives and makes us more competent communicators.

Handling Conflict Better

Conflict is inevitable and it is not inherently negative. A key part of developing interpersonal communication competence involves being able to effectively manage the conflict you will encounter in all your relationships. One key part of handling conflict better is to notice patterns of conflict in specific relationships and to generally have an idea of what causes you to react negatively and what your reactions usually are.

Identifying Conflict Patterns

Much of the research on conflict patterns has been done on couples in romantic relationships, but the concepts and findings are applicable to other relationships. Four common triggers for conflict are criticism, demand, cumulative annoyance, and rejection (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000). We all know from experience that criticism, or comments that evaluate another person’s personality, behavior, appearance, or life choices, may lead to conflict. Comments do not have to be meant as criticism to be perceived as such. If Gary comes home from college for the weekend and his mom says, “Looks like you put on a few pounds,” she may view this as a statement of fact based on observation. Gary, however, may take the comment personally and respond negatively back to his mom, starting a conflict that will last for the rest of his visit. A simple but useful strategy to manage the trigger of criticism is to follow the old adage “Think before you speak.” In many cases, there are alternative ways to phrase things that may be taken less personally, or we may determine that our comment doesn’t need to be spoken at all. I’ve learned that a majority of the thoughts that we have about another person’s physical appearance, whether positive or negative, do not need to be verbalized. Ask yourself, “What is my motivation for making this comment?” and “Do I have anything to lose by not making this comment?” If your underlying reasons for asking are valid, perhaps there is another way to phrase your observation. If Gary’s mom is worried about his eating habits and health, she could wait until they’re eating dinner and ask him how he likes the food choices at school and what he usually eats.

Demands also frequently trigger conflict, especially if the demand is viewed as unfair or irrelevant. It’s important to note that demands rephrased as questions may still be or be perceived as demands. Tone of voice and context are important factors here. When you were younger, you may have asked a parent, teacher, or elder for something and heard back “Ask nicely.” As with criticism, thinking before you speak and before you respond can help manage demands and minimize conflict episodes. As we discussed earlier, demands are sometimes met with withdrawal rather than a verbal response. If you are doing the demanding, remember a higher level of information exchange may make your demand clearer or more reasonable to the other person. If you are being demanded of, responding calmly and expressing your thoughts and feelings are likely more effective than withdrawing, which may escalate the conflict.

Cumulative annoyance is a building of frustration or anger that occurs over time, eventually resulting in a conflict interaction. For example, your friend shows up late to drive you to class three times in a row. You didn’t say anything the previous times, but on the third time you say, “You’re late again! If you can’t get here on time, I’ll find another way to get to class.” Cumulative annoyance can build up like a pressure cooker, and as it builds up, the intensity of the conflict also builds. Criticism and demands can also play into cumulative annoyance. We have all probably let critical or demanding comments slide, but if they continue, it becomes difficult to hold back, and most of us have a breaking point. The problem here is that all the other incidents come back to your mind as you confront the other person, which usually intensifies the conflict. You’ve likely been surprised when someone has blown up at you due to cumulative annoyance or surprised when someone you have blown up at didn’t know there was a problem building. A good strategy for managing cumulative annoyance is to monitor your level of annoyance and occasionally let some steam out of the pressure cooker by processing through your frustration with a third party or directly addressing what is bothering you with the source.

No one likes the feeling of rejection. Rejection can lead to conflict when one person’s comments or behaviors are perceived as ignoring or invalidating the other person. Vulnerability is a component of any close relationship. When we care about someone, we verbally or nonverbally communicate. We may tell our best friend that we miss them, or plan a home-cooked meal for our partner who is working late. The vulnerability that underlies these actions comes from the possibility that our relational partner will not notice or appreciate them. When someone feels exposed or rejected, they often respond with anger to mask their hurt, which ignites a conflict. Managing feelings of rejection is difficult because it is so personal, but controlling the impulse to assume that your relational partner is rejecting you, and engaging in communication rather than reflexive reaction, can help put things in perspective. If your partner doesn’t get excited about the meal you planned and cooked, it could be because he or she is physically or mentally tired after a long day. Concepts discussed in chapter 2 can be useful here, as perception checking, taking inventory of your attributions, and engaging in information exchange to help determine how each person is punctuating the conflict are useful ways of managing all four of the triggers discussed.

Interpersonal conflict may take the form of serial arguing, which is a repeated pattern of disagreement over an issue. Serial arguments do not necessarily indicate negative or troubled relationships, but any kind of patterned conflict is worth paying attention to. There are three patterns that occur with serial arguing: repeating, mutual hostility, and arguing with assurances (Johnson & Roloff, 2000). The first pattern is repeating, which means reminding the other person of your complaint (what you want them to start/stop doing). The pattern may continue if the other person repeats their response to your reminder. For example, if Marita reminds Kate that she doesn’t appreciate her sarcastic tone, and Kate responds, “I’m soooo sorry, I forgot how perfect you are,” then the reminder has failed to effect the desired change. A predictable pattern of complaint like this leads participants to view the conflict as irresolvable. The second pattern within serial arguments is mutual hostility, which occurs when the frustration of repeated conflict leads to negative emotions and increases the likelihood of verbal aggression. Again, a predictable pattern of hostility makes the conflict seem irresolvable and may lead to relationship deterioration. Whereas the first two patterns entail an increase in pressure on the participants in the conflict, the third pattern offers some relief. If people in an interpersonal conflict offer verbal assurances of their commitment to the relationship, then the problems associated with the other two patterns of serial arguing may be ameliorated. Even though the conflict may not be solved in the interaction, the verbal assurances of commitment imply that there is a willingness to work on solving the conflict in the future, which provides a sense of stability that can benefit the relationship. Although serial arguing is not inherently bad within a relationship, if the pattern becomes more of a vicious cycle, it can lead to alienation, polarization, and an overall toxic climate, and the problem may seem so irresolvable that people feel trapped and terminate the relationship (Christensen & Jacobson, 2000). There are some negative, but common, conflict reactions we can monitor and try to avoid, which may also help prevent serial arguing.

Two common conflict pitfalls are one-upping and mindreading (Gottman, 1994). is a quick reaction to communication from another person that escalates the conflict. If Sam comes home late from work and Nicki says, “I wish you would call when you’re going to be late” and Sam responds, “I wish you would get off my back,” the reaction has escalated the conflict. Mindreading is communication in which one person attributes something to the other using generalizations. If Sam says, “You don’t care whether I come home at all or not!” she is presuming to know Nicki’s thoughts and feelings. Nicki is likely to respond defensively, perhaps saying, “You don’t know how I’m feeling!” One-upping and mindreading are often reactions that are more reflexive than deliberate. Remember concepts like attribution and punctuation in these moments. Nicki may have received bad news and was eager to get support from Sam when she arrived home. Although Sam perceives Nicki’s comment as criticism and justifies her comments as a reaction to Nicki’s behavior, Nicki’s comment could actually be a sign of their closeness, in that Nicki appreciates Sam’s emotional support. Sam could have said, “I know, I’m sorry, I was on my cell phone for the past hour with a client who had a lot of problems to work out.” Taking a moment to respond mindfully rather than react with a knee-jerk reflex can lead to information exchange, which could deescalate the conflict.

Slipperroom – Mysterion the Mind Reader – CC BY-NC 2.0

Validating the person with whom you are in conflict can be an effective way to deescalate conflict. While avoiding or retreating may seem like the best option at the moment, one of the key negative traits found in research on married couples’ conflicts was withdrawal, which as we learned before may result in a demand-withdrawal pattern of conflict. Often validation can be as simple as demonstrating good listening skills discussed earlier in this book by making eye contact and giving verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues like saying “mmm-hmm” or nodding your head (Gottman, 1994). This doesn’t mean that you have to give up your own side in a conflict or that you agree with what the other person is saying; rather, you are hearing the other person out, which validates them and may also give you some more information about the conflict that could minimize the likelihood of a reaction rather than a response.

As with all the aspects of communication competence we have discussed so far, you cannot expect that everyone you interact with will have the same knowledge of communication that you have after reading this book. But it often only takes one person with conflict management skills to make an interaction more effective. Remember that it’s not the quantity of conflict that determines a relationship’s success; it’s how the conflict is managed, and one person’s competent response can deescalate a conflict. Now we turn to a discussion of negotiation steps and skills as a more structured way to manage conflict.

Negotiating

We negotiate daily. We may negotiate with a professor to make up a missed assignment or with our friends to plan activities for the weekend. Negotiation in interpersonal conflict refers to the process of attempting to change or influence conditions within a relationship. The negotiation skills discussed next can be adapted to all types of relational contexts, from romantic partners to coworkers. The stages of negotiating are prenegotiation, opening, exploration, bargaining, and settlement (Hargie, 2011).

In the prenegotiation stage, you want to prepare for the encounter. If possible, let the other person know you would like to talk to them, and preview the topic, so they will also have the opportunity to prepare. While it may seem awkward to “set a date” to talk about a conflict, if the other person feels like they were blindsided, their reaction could be negative. Make your preview simple and nonthreatening by saying something like “I’ve noticed that we’ve been arguing a lot about who does what chores around the house. Can we sit down and talk tomorrow when we both get home from class?” Obviously, it won’t always be feasible to set a date if the conflict needs to be handled immediately because the consequences are immediate or if you or the other person has limited availability. In that case, you can still prepare, but make sure you allow time for the other person to digest and respond. During this stage, you also want to figure out your goals for the interaction by reviewing your instrumental, relational, and self-presentation goals. Is getting something done, preserving the relationship, or presenting yourself in a certain way the most important? For example, you may highly rank the instrumental goal of having a clean house, or the relational goal of having pleasant interactions with your roommate, or the self-presentation goal of appearing nice and cooperative. Whether your roommate is your best friend from high school or a stranger the school matched you up with could determine the importance of your relational and self-presentation goals. At this point, your goal analysis may lead you away from negotiation—remember, as we discussed earlier, avoiding can be an appropriate and effective conflict management strategy. If you decide to proceed with the negotiation, you will want to determine your ideal outcome and your bottom line, or the point at which you decide to break off the negotiation. It’s very important that you realize there is a range between your ideal and your bottom line and that remaining flexible is key to a successful negotiation—remember, through collaboration a new solution could be found that you didn’t think of.

In the opening stage of the negotiation, you want to set the tone for the interaction because the other person will be likely to reciprocate. Generally, it is good to be cooperative and pleasant, which can help open the door for collaboration. You also want to establish common ground by bringing up overlapping interests and using “we” language. It would not be competent to open the negotiation with “You’re such a slob! Didn’t your mom ever teach you how to take care of yourself?” Instead, you may open the negotiation by making small talk about classes that day and then move into the issue at hand. You could set a good tone and establish common ground by saying, “We both put a lot of work into setting up and decorating our space, but now that classes have started, I’ve noticed that we’re really busy and some chores are not getting done.” With some planning and a simple opening like that, you can move into the next stage of negotiation.

There should be a high level of information exchange in the exploration stage. The overarching goal in this stage is to get a panoramic view of the conflict by sharing your perspective and listening to the other person. In this stage, you will likely learn how the other person is punctuating the conflict. Although you may have been mulling over the mess for a few days, your roommate may just now be aware of the conflict. She may also inform you that she usually cleans on Sundays but didn’t get to last week because she unexpectedly had to visit her parents. The information that you gather here may clarify the situation enough to end the conflict and cease negotiation. If negotiation continues, the information will be key as you move into the bargaining stage.

The bargaining stage is where you make proposals and concessions. The proposal you make should be informed by what you learned in the exploration stage. Flexibility is important here, because you may have to revise your ideal outcome and bottom line based on new information. If your plan was to have a big cleaning day every Thursday, you may now want to propose to have the roommate clean on Sunday while you clean on Wednesday. You want to make sure your opening proposal is reasonable and not presented as an ultimatum. “I don’t ever want to see a dish left in the sink” is different from “When dishes are left in the sink too long, they stink and get gross. Can we agree to not leave any dishes in the sink overnight?” Through the proposals you make, you could end up with a win/win situation. If there are areas of disagreement, however, you may have to make concessions or compromise, which can be a partial win or a partial loss. If you hate doing dishes but don’t mind emptying the trash and recycling, you could propose to assign those chores based on preference. If you both hate doing dishes, you could propose to be responsible for washing your own dishes right after you use them. If you really hate dishes and have some extra money, you could propose to use disposable (and hopefully recyclable) dishes, cups, and utensils.

In the settlement stage, you want to decide on one of the proposals and then summarize the chosen proposal and any related concessions. It is possible that each party can have a different view of the agreed solution. If your roommate thinks you are cleaning the bathroom every other day and you plan to clean it on Wednesdays, then there could be future conflict. You could summarize and ask for confirmation by saying, “So, it looks like I’ll be in charge of the trash and recycling, and you’ll load and unload the dishwasher. Then I’ll do a general cleaning on Wednesdays and you’ll do the same on Sundays. Is that right?” Last, you’ll need to follow up on the solution to make sure it’s working for both parties. If your roommate goes home again next Sunday and doesn’t get around to cleaning, you may need to go back to the exploration or bargaining stage.

Conflict Management Strategies

While many of the below strategies have been previously discussed, they warrant another mention as they are strategies that can help to manage conflict in a positive manner.

Defensiveness versus Supportiveness

Face-Detracting and Face-Saving

Communication is not competition. Communication is the sharing of understanding and meaning, but does everyone always share equally? People struggle for control, limit access to resources and information as part of territorial displays, and otherwise use the process of communication to engage in competition. People also use communication for collaboration. Both competition and collaboration can be observed in communication interactions, but there are two concepts central to both: face-detracting and face-saving strategies.

Face-detracting strategies involve messages or statements that take away from the respect, integrity, or credibility of a person. Face-saving strategies protect credibility and separate message from the messenger. For example, you might say that “sales were down this quarter,” without specifically noting who was responsible. Sales were simply down. If, however, you ask, “How does the sales manager explain the decline in sales?” you have specifically connected an individual with the negative news. While we may want to specifically connect tasks and job responsibilities to individuals and departments, in terms of language each strategy has distinct results.

Face-detracting strategies often produce a defensive communication climate, inhibit listening, and allow for little room for collaboration. To save face is to raise the issue while preserving a supportive climate, allowing room in the conversation for constructive discussions and problem-solving. By using a face-saving strategy to shift the emphasis from the individual to the issue, we avoid power struggles and personalities, providing each other space to save face (Donohue, W. and Klot, R., 1992).

Empathy

Communication involves not only the words we write or speak, but how and when we write or say them. The way we communicate also carries meaning, and empathy for the individual involves attending to this aspect of interaction. Empathetic listening involves listening to both the literal and implied meanings within a message. For example, the implied meaning might involve understanding what has led this person to feel this way. By paying attention to feelings and emotions associated with content and information, we can build relationships and address conflict more constructively. In management, negotiating conflict is a common task and empathy is one strategy to consider when attempting to resolve issues.

Managing your Emotions

Have you ever seen red, or perceived a situation through rage, anger, or frustration? Then you know that you cannot see or think clearly when you are experiencing strong emotions. There will be times in the work environment when emotions run high. Your awareness of them can help you clear your mind and choose to wait until the moment has passed to tackle the challenge.

“Never speak or make a decision in anger” is one common saying that holds true, but not all emotions involve fear, anger, or frustration. A job loss can be a sort of professional death for many, and the sense of loss can be profound. The loss of a colleague to a layoff while retaining your position can bring pain as well as relief, and a sense of survivor’s guilt. Emotions can be contagious in the workplace, and fear of the unknown can influence people to act in irrational ways. The wise business communicator can recognize when emotions are on edge in themselves or others, and choose to wait to communicate, problem-solve, or negotiate until after the moment has passed.

Listen without Interrupting

If you are on the receiving end of an evaluation, start by listening without interruption. Interruptions can be internal and external, and warrant further discussion. If your supervisor starts to discuss a point and you immediately start debating the point in your mind, you are paying attention to yourself and what you think they said or are going to say, and not that which is actually communicated. This gives rise to misunderstandings and will cause you to lose valuable information you need to understand and address the issue at hand.

External interruptions may involve your attempt to get a word in edgewise and may change the course of the conversation. Let them speak while you listen, and if you need to take notes to focus your thoughts, take clear notes of what is said, also noting points to revisit later. External interruptions can also take the form of a telephone ringing, a “text message has arrived” chime, or a coworker dropping by in the middle of the conversation.

As an effective business communicator, you know all too well to consider the context and climate of the communication interaction when approaching the delicate subject of evaluations or criticism. Choose a time and place free from interruption. Choose one outside the common space where there may be many observers. Turn off your cell phone. Choose face-to-face communication instead of an impersonal e-mail. By providing a space free of interruption, you are displaying respect for the individual and the information.

Determine the Speaker’s Intent

We have discussed previews as a normal part of the conversation, and in this context, they play an important role. People want to know what is coming and generally dislike surprises, particularly when the context of an evaluation is present. If you are on the receiving end, you may need to ask a clarifying question if it doesn’t count as an interruption. You may also need to take notes and write down questions that come to mind to address when it is your turn to speak. As a manager, be clear and positive in your opening and lead with praise. You can find one point, even if it is only that the employee consistently shows up to work on time, to highlight before transitioning to a performance issue.

Indicate You Are Listening

In mainstream U.S. culture, eye contact is a signal that you are listening and paying attention to the person speaking. Take notes, nod your head, or lean forward to display interest and listening. Regardless of whether you are the employee receiving the criticism or the supervisor delivering it, displaying listening behavior engenders a positive climate that helps mitigate the challenge of negative news or constructive criticism.

Paraphrase

Restate the main points to paraphrase what has been discussed. This verbal display allows for clarification and acknowledges receipt of the message.

If you are the employee, summarize the main points and consider steps you will take to correct the situation. If none come to mind or you are nervous and are having a hard time thinking clearly, state out loud the main point and ask if you can provide solution steps and strategies at a later date. You can request a follow-up meeting if appropriate, or indicate you will respond in writing via e-mail to provide the additional information.

If you are the employer, restate the main points to ensure that the message was received, as not everyone hears everything that is said or discussed the first time it is presented. Stress can impair listening, and paraphrasing the main points can help address this common response.

Learn from Experience

Every communication interaction provides an opportunity for learning if you choose to see it. Sometimes the lessons are situational and may not apply in future contexts. Other times the lessons learned may well serve you across your professional career. Taking notes for yourself to clarify your thoughts, much like a journal, serve to document and help you see the situation more clearly.

Recognize that some aspects of communication are intentional, and may communicate meaning, even if it is hard to understand. Also, know that some aspects of communication are unintentional, and may not imply meaning or design. People make mistakes. They say things they should not have said. Emotions are revealed that are not always rational, and not always associated with the current context. A challenging morning at home can spill over into the work day and someone’s bad mood may have nothing to do with you.

Try to distinguish between what you can control and what you cannot, and always choose professionalism.

Understanding Cultural Influences

The strongest cultural factor that influences your conflict approach is whether you belong to an individualistic or collectivistic culture (Ting-Toomey, 1997). People raised in collectivistic cultures often view direct communication regarding conflict as personal attacks (Nishiyama, 1971), and consequently are more likely to manage conflict through avoidance or accommodation. From a collectivistic perspective, the underlying goal in a conflict is not the preservation and manifestation of individual rights and attributes, but rather the preservation of relationships. In this approach, individual rights are superseded by group interest.

The predominant perspective of individualism is to have one’s own ideas and act according to the courage of one’s convictions. Any perceived constraint on individual freedom is likely to pose immediate problems and require a response. Typically the most appropriate response in a conflict situation involves a direct or honest expression of one’s ideas. People from individualistic cultures feel comfortable agreeing to disagree and don’t particularly see such clashes as personal affronts (Ting-Toomey, 1985). They are more likely to assert their own position in a conflict, rather than seeking compromise or accommodation.

Gudykunst & Kim (2003) suggest that if you are an individualist in a dispute with a collectivist, you should consider the following:

- Recognize that collectivists may prefer to have a third party mediate the conflict so that those in conflict can manage their disagreement without direct confrontation to preserve relational harmony.

- Use more indirect verbal messages.

- Let go of the situation if the other person does not recognize the conflict exists or does not want to deal with it.

If you are a collectivist and are conflicting with someone from an individualistic culture, the following guidelines may help:

- Recognize that individualists often separate conflicts from people. It’s not personal.

- Use an assertive style, filled with “I” messages, and be direct by candidly stating your opinions and feelings.

- Manage conflicts even if you’d rather avoid them.

Effective conflict resolution serves all parties and preserves harmony. In cross-cultural situations, many scholars advocate the use of face negotiation techniques, as outlined below.

Face negotiation

According to face negotiation theory, people in all cultures share the need to maintain and negotiate face. Some cultures – and individuals – tend to be more concerned with self-face, often associated with individualism. Individualistic cultures prefer a direct way of addressing conflicts, according to the chart presented earlier, a dominating style or, optimally, a collaborating approach. Addressing a conflict directly is something that particular cultures or people may prefer not to do. Conflict resolution, in this case, may become confrontational, leading potentially to a loss of face for the other party. Collectivists – cultures or individuals – tend to be more concerned with other-face and may prefer an indirect approach, using subtle or unspoken means to deal with conflict (avoiding, withdrawing, compromising), so as not to challenge the face of the other.

Conflict Face-Negotiation Theory recommends a four-skills approach to managing conflict across cultures. These skills are:

- Mindful Listening: Pay special attention to the cultural and personal assumptions being expressed in the conflict interaction. Paraphrase verbal and nonverbal content and emotional meaning of the other party’s message to check for accurate interpretation.

- Mindful Reframing: This is another face-honoring skill that requires the creation of alternative contexts to shape our understanding of the conflict behavior.

- Collaborative Dialog: An exchange of dialog that is oriented fully in the present moment and builds on Mindful Listening and Mindful Reframing to practice communicating with different linguistic or contextual resources.

- Culture-based Conflict Resolution Steps is a seven-step conflict resolution model that guides conflicting groups to identify the background of a problem, analyze the cultural assumptions and underlying values of a person in a conflict situation, and promotes ways to achieve harmony and share a common goal. The process entails asking yourself:

- What is my cultural and personal assessment of the problem?

- Why did I form this assessment and what is the source of this assessment?

- What are the underlying assumptions or values that drive my assessment?

- How do I know they are relative or valid in this conflict context?

- What reasons might I have for maintaining or changing my underlying conflict premise?

- How should I change my cultural or personal premises into the direction that promotes deeper

intercultural understanding?

- How should I adapt on both verbal and nonverbal conflict style levels in order to display facework sensitive behaviors and to facilitate a productive common-interest outcome?

(Ting-Toomey, 2012; Fisher-Yoshida, 2005; Mezirow, 2000)

Forgiveness

Individuals tend to experience a wide array of complex emotions following a relational transgression. These emotions are shown to have utility as an initial coping mechanism. For example, fear can result in a protective orientation following a serious transgression; sadness results in contemplation and reflection while disgust causes us to repel from its source. However, beyond the initial situation, these emotions can be detrimental to one’s mental and physical state. Consequently, forgiveness is viewed as a more productive means of dealing with the transgression along with engaging the one who committed the transgression.

Forgiving is not the act of excusing or condoning. Rather, it is the process whereby negative emotions are transformed into positive emotions for the purpose of bringing emotional normalcy to a relationship. In order to achieve this transformation, the offended must forgo retribution and claims for retribution. McCullough, Worthington, and Rachal (1997) defined forgiveness as a, “set of motivational changes whereby one becomes (a) decreasingly motivated to retaliate against an offending relationship partner, (b) decreasingly motivated to maintain estrangement from the offender, and (c) increasingly motivated by conciliation and goodwill for the offender, despite the offender’s hurtful actions”. In essence, relational partners choose constructive behaviors that show an emotional commitment and willingness to sacrifice in order to achieve a state of forgiveness.

Dimensions of forgiveness

The link between reconciliation and forgiveness involves exploring two dimensions of forgiveness: intrapsychic and interpersonal. The intrapsychic dimension relates to the cognitive processes and interpretations associated with a transgression (i.e. internal state), whereas interpersonal forgiveness is the interaction between relational partners. Total forgiveness is defined as including both the intrapsychic and interpersonal components which bring about a return to the conditions prior to the transgression. To only change one’s internal state is silent forgiveness, and only having interpersonal interaction is considered hollow forgiveness.

However, some scholars contend that these two dimensions (intrapsychic and interpersonal) are independent as the complexities associated with forgiveness involve gradations of both dimensions. For example, a partner may not relinquish negative emotions yet choose to remain in the relationship because of other factors (e.g., children, financial concerns, etc.). Conversely, one may grant forgiveness and release all negative emotions directed toward their partner, and still exit the relationship because trust cannot be restored. Given this complexity, research has explored whether the transformation of negative emotions to positive emotions eliminates negative affect associated with a given offense. The conclusions drawn from this research suggest that no correlation exists between forgiveness and unforgiveness. Put simply, while forgiveness may be granted for a given transgression, the negative effect may not be reduced a corresponding amount.

Determinants of forgiveness

McCullough et al. (1998) outlined predictors of forgiveness into four broad categories

- Personality traits of both partners

- Relationship quality

- Nature of the transgression

- Social-cognitive variables

While personality variables and characteristics of the relationship are preexisting to the occurrence of forgiveness, the nature of the offense and social-cognitive determinants become apparent at the time of the transgression.

Personality traits of both partners

Forgivingness is defined as one’s general tendency to forgive transgressions. However, this tendency differs from forgiveness which is a response associated with a specific transgression. Listed below are characteristics of the forgiving personality as described by Emmons (2000).

- Does not seek revenge; effectively regulates negative affect

- Strong desire for a relationship free of conflict

- Shows empathy toward the offender

- Does not personalize hurt associated with transgression

In terms of personality traits, agreeableness and neuroticism (i.e., instability, anxiousness, aggression) show consistency in predicting forgivingness and forgiveness. Since forgiveness requires one to discard any desire for revenge, a vengeful personality tends to not offer forgiveness and may continue to harbor feelings of vengeance long after the transgression occurred.

Research has shown that agreeableness is inversely correlated with motivations for revenge and avoidance, as well as positively correlated with benevolence. As such, one who demonstrates the personality trait of agreeableness is prone to forgiveness as well as has a general disposition of forgivingness. Conversely, neuroticism was positively correlated with avoidance and vengefulness but negatively correlated with benevolence. Consequently, a neurotic personality is less apt to forgive or to have a disposition of forgivingness.

Though the personality traits of the offended have a predictive value of forgiveness, the personality of the offender also has an effect on whether forgiveness is offered. Offenders who show sincerity when seeking forgiveness and are persuasive in downplaying the impact of the transgression will have a positive effect on whether the offended will offer forgiveness.

Narcissistic personalities, for example, may be categorized as persuasive transgressors. This is driven by the narcissist to downplay their transgressions, seeing themselves as perfect and seeking to save face at all costs. Such a dynamic suggests that personality determinants of forgiveness may involve not only the personality of the offended but also that of the offender.

Relationship quality

The quality of a relationship between offended and offending partners can affect whether forgiveness is both sought and given. In essence, the more invested one is in a relationship, the more prone one is to minimize the hurt associated with transgressions and seek reconciliation.

McCullough et al. (1998) provides seven reasons behind why those in relationships will seek to forgive:

- High investment in the relationship (e.g., children, joint finances, etc.)

- Views relationship as long term commitment

- Have a high degree of common interests

- Is selfless in regard to their partner

- Willingness to take the viewpoint of partner (i.e. empathy)

- Assumes motives of partner are in the best interest of relationship (e.g., criticism is taken as constructive feedback)

- Willingness to apologize for transgressions

Relationship maintenance activities are a critical component to maintaining high-quality relationships. While being heavily invested tends to lead to forgiveness, one may be in a skewed relationship where the partner who is heavily invested is actually under benefitted. This leads to an over benefitted partner who is likely to take the relationship for granted and will not be as prone to exhibit relationship repair behaviors. As such, being mindful of the quality of a relationship will best position partners to address transgressions through a stronger willingness to forgive and seek to normalize the relationship.

Another relationship factor that affects forgiveness is the history of past conflict. If past conflicts ended badly (i.e., reconciliation/forgiveness was either not achieved or achieved after much conflict), partners will be less prone to seek out or offer forgiveness. As noted earlier, maintaining a balanced relationship (i.e. no partner over/under benefitted) has a positive effect on relationship quality and tendency to forgive. In that same vein, partners are more likely to offer forgiveness if their partners had recently forgiven them for a transgression. However, if a transgression is repeated resentment begins to build which has an adverse effect on the offended partner’s desire to offer forgiveness.

Nature of the transgression

The most notable feature of a transgression to have an effect on forgiveness is the seriousness of the offense. Some transgressions are perceived as being so serious that they are considered unforgivable. To counter the negative affect associated with a severe transgression, the offender may engage in repair strategies to lessen the perceived hurt of the transgression. The offender’s communication immediately following a transgression has the greatest predictive value on whether forgiveness will be granted.

Consequently, offenders who immediately apologize, take responsibility, and show remorse have the greatest chance of obtaining forgiveness from their partner.Further, self-disclosure of a transgression yields much greater results than if a partner is informed of the transgression through a third party. By taking responsibility for one’s actions and being forthright through self-disclosure of an offense, partners may actually form closer bonds from the reconciliation associated with a serious transgression. As noted in the section on personality, repeated transgressions cause these relationship repair strategies to have a more muted effect as resentment begins to build and trust erodes.

Social-cognitive variables

Attributions of responsibility for a given transgression may have an adverse effect on forgiveness. Specifically, if a transgression is viewed as intentional or malicious, the offended partner is less likely to feel empathy and forgive. Based on the notion that forgiveness is driven primarily by empathy, the offender must accept responsibility and seek forgiveness immediately following the transgression, as apologies have shown to elicit empathy from the offended partner. The resulting feelings of empathy elicited in the offended partner may cause them to better relate to the guilt and loneliness their partner may feel as a result of the transgression. In this state of mind, the offended partner is more likely to seek to normalize the relationship through granting forgiveness and restoring closeness with their partner.

Key Takeaways

- Interpersonal conflict is an inevitable part of relationships that, although not always negative, can take an emotional toll on relational partners unless they develop skills and strategies for managing conflict.