Learning Objectives

- Discuss some of the social norms that guide conversational interaction.

- Identify some of the ways in which language varies based on cultural context.

- Explain the role that accommodation and code-switching play in communication.

- Discuss cultural bias in relation to specific cultural identities.

Society and culture influence the words that we speak, and the words that we speak influence society and culture. Such a cyclical relationship can be difficult to understand, but many of the examples throughout this chapter and examples from our own lives help illustrate this point. One of the best ways to learn about society, culture, and language is to seek out opportunities to go beyond our typical comfort zones. Studying abroad, for example, brings many challenges that can turn into valuable lessons.

Social Context

We arrive at meaning through conversational interaction, which follows many social norms and rules. Rules are explicitly stated conventions (“Look at me when I’m talking to you.”), and norms are implicit (saying you’ve got to leave before you actually do to politely initiate the end of a conversation). To help conversations function meaningfully, we have learned social norms and internalized them to such an extent that we do not often consciously enact them. Instead, we rely on routines and roles (as determined by social forces) to help us proceed with verbal interaction, which also helps determine how a conversation will unfold. Our various social roles influence meaning and how we speak. For example, a person may say, “As a longtime member of this community…” or “As a first-generation college student….” Such statements cue others into the personal and social context from which we are speaking, which helps them better interpret our meaning.

One social norm that structures our communication is turn-taking. People need to feel like they are contributing something to an interaction, so turn-taking is a central part of how conversations play out (Crystal, 2005). Although we sometimes talk at the same time as others or interrupt them, there are numerous verbal and nonverbal cues, almost like a dance, that are exchanged between speakers that let people know when their turn will begin or end. Conversations do not always neatly progress from beginning to end, with shared understanding along the way. There is a back and forth that is often verbally managed through rephrasing (“Let me try that again,”) and clarification (“Does that make sense?”) (Crystal, 2005).

We also have certain units of speech that facilitate turn-taking. Adjacency pairs are related communication structures that come one after the other (adjacent to each other) in an interaction (Crystal, 2005). For example, questions are followed by answers, greetings are followed by responses, compliments are followed by a thank you, and informative comments are followed by an acknowledgment. These are the skeletal components that make up our verbal interactions, and they are largely social in that they facilitate our interactions. When these sequences don’t work out, confusion, miscommunication, or frustration may result.

Some conversational elements are highly scripted or ritualized, especially the beginning and end of an exchange and topic changes (Crystal, 2005). Conversations often begin with a standard greeting and then proceed to “safe” exchanges about things in the immediate field of experience of the communicators (a comment on the weather or noting something going on in the scene). Once the ice is broken, people can move on to other more content-specific exchanges. Once conversing, before we can initiate a topic change, it is a social norm to let the current topic being discussed play itself out or continue until the person who introduced the topic seems satisfied. We then usually try to find a relevant tie-in or segue that acknowledges the previous topic, in turn acknowledging the speaker, before actually moving on. Changing the topic without following such social conventions might indicate to the other person that you were not listening or are simply rude.

Social norms influence how conversations start and end and how speakers take turns to keep the conversation going.

Felipe Cabrera – conversation – CC BY 2.0.

Ending a conversation is similarly complex. I’m sure we’ve all been in a situation where we are “trapped” in a conversation we want to get out of. Just walking away or ending a conversation without engaging in socially acceptable “leave-taking behaviors” would be considered a breach of social norms. Topic changes are often places where people can leave a conversation, but it is still routine for us to give a special reason for leaving, often in an apologetic tone (whether we mean it or not). Generally though, conversations come to an end through the cooperation of both people, as they offer and recognize typical signals that a topic area has been satisfactorily covered or that one or both people need to leave. It is customary in the United States for people to say they have to leave before they actually do and for that statement to be dismissed or ignored by the other person until additional leave-taking behaviors are enacted. When such cooperation is lacking, an awkward silence or abrupt ending can result, and as we’ve already learned, US Americans are not big fans of silence. Silence is not viewed the same way in other cultures, which leads us to our discussion of cultural context.

In the typical language learning environment, it is not possible to expose learners to all the varieties of language use they might encounter. However, it certainly is possible to increase learners’ awareness of socio-cultural issues. One of those is the existence of language registers, the idea that we adjust the language we use – in terms of formality, tone, and even vocabulary – in response to the context in which we find ourselves. Learners need to be aware of how language use could be adjusted in formal face-to-face settings, such as in a work environment, to highly informal, online settings, such as social media postings. This involves looking beyond grammatical correctness to language in use. Pragmatics, another field of interest in sociolinguistics, deals with the nature of language as it occurs in actual social use. The meaning of what is said in conversation may be quite different from the literal meaning of the words used. A statement made in an ironic, sarcastic, or humorous tone may have a meaning diametrically opposed to its surface meaning. Answering “oh, sure” in American English to a statement or question can be a positive affirmation or be intended to ridicule what the interlocutor has said. Such nuances are important for being able to function in the target culture. This kind of sociocultural competence is not easy to acquire, as pragmatics does not involve learning a fixed set of rules. Rather, inference and intuition play a major role, as can emotions. Awareness of the dynamics of language use in conversation can help one be a better informed and literate speaker of any language. Pragmatic competence is particularly important in online exchanges, in which the non-verbal cues signaling intent and attitude are not available

Cultural Context

Culture isn’t solely determined by a person’s native language or nationality. It’s true that languages vary by country and region and that our language influences our realities, but even people who speak the same language experience cultural differences because of their various intersecting cultural identities and personal experiences.

The actual language we speak plays an important role in shaping our reality. Comparing languages, we can see differences in how we can talk about the world. In English, we have the words grandfather and grandmother, but no single word distinguishes between a maternal grandfather and a paternal grandfather. But in Swedish, there’s a specific word for each grandparent: morfar is mother’s father, farfar is father’s father, farmor is father’s mother, and mormor is mother’s mother (Crystal, 2005). In this example, we can see that the words available to us, based on the language we speak, influence how we talk about the world due to differences in and limitations of vocabulary.

The notion that language shapes our view of reality and our cultural patterns is best represented by the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. The link between language and culture was famously described in the work of Benjamin Whorf and Edward Sapir. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis postulates that your native language has a profound influence on how you see the world, and that you perceive reality in the context of the language you have available to describe it. According to Sapir (1929), “The ‘real world’ is to a large extent unconsciously built up on the language habits of the group. The worlds in which different societies live are distinct, not merely the same world with different labels attached” (p. 162). From this perspective, all language use – from the words we use to describe objects to the way sentences are structured – is tied closely to the culture in which it is spoken.

Whorf studied Native American languages such as Hopi and was struck by differences to English which pointed to different ways of viewing the world, for example, in how time is expressed. Taken to its extreme, this kind of linguistic determinism would prevent native speakers of different languages from having the same thoughts or sharing a worldview. They would be, in a sense, captives of their native language, unable to gain different perspectives on reality.

More widely accepted today is the concept of linguistic relativity, meaning that language shapes our views of the world but is not an absolute determiner of how or what we think. Linguistic relativity suggests that language influences thought in worldviews, and therefore differences among languages cause differences in the thoughts of their speakers. Linguist Steven Pinker’s (2007) research has shown that, in fact, language is not the only existing means of thought. It is possible for us to picture reality through mental images or shapes. In recent years, there have been a number of studies on the perception of colors related to available color words. Languages differ in this area. Some, for example, do not have separate words for blue and green. In the Tarahumara indigenous language of Mexico, one single word, siyoname, is used for both colors (Kay & Kempton, 1984). Such studies, as well as similar examinations of concepts such as numbers, shapes, generally have shown that “language has some effect on perception, but it does not define perception.” (Hua, 2014, p. 178). Experiments have shown that in some cases, where specific terms for colors do not exist, that does not prevent color recognition: “although the Dani, a New Guinea tribe, use only two color terms . . . it was found that they could recognize and distinguish between subtle shades of colors that their language had no names for (e.g. pale blue vs. turquoise)” (Holmes, 2001, p. 324). This is in line with current linguistic thought that there is a more complex, reciprocal relationship between language and culture.

The following video explores this concept providing examples of different cultures.

Culturally influenced differences in language and meaning can lead to some interesting encounters, ranging from awkward to informative to disastrous. In terms of awkwardness, you have likely heard stories of companies that failed to exhibit communication competence in their naming and/or advertising of products in another language. For example, in Taiwan, Pepsi used the slogan “Come Alive with Pepsi” only to later find out that when translated it meant, “Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the dead” (Kwintessential Limited, 2012). Similarly, American Motors introduced a new car called the Matador to the Puerto Rico market only to learn that Matador means “killer,” which wasn’t very comforting to potential buyers (Kwintessential, 2012). At a more informative level, the words we use to give positive reinforcement are culturally relative. In the United States and England, parents may positively and negatively reinforce their child’s behavior by saying, “Good kid.” There isn’t an equivalent for such a phrase in other European languages, so the usage in only these two countries has been traced back to the puritan influence on beliefs about good and bad behavior (Wierzbicka, 2004). In terms of disastrous consequences, one of the most publicized and deadliest cross-cultural business mistakes occurred in India in 1984. Union Carbide, an American company, controlled a plant used to make pesticides. The company underestimated the amount of cross-cultural training that would be needed to allow the local workers, many of whom were not familiar with the technology or language/jargon used in the instructions for plant operations to do their jobs. This lack of competent communication led to a gas leak that immediately killed more than two thousand people and over time led to more than five hundred thousand injuries (Varma, 2012).

In recent years there has been a growing recognition that culture and language cannot be separated and that culture permeates all aspects of language. (Godwin-Jones, 2016). If, for example, a language has different personal pronouns for direct address, such as the informal tu in French and the formal vous, both meaning ‘you’, that distinction is a reflection of one aspect of the culture. It indicates that there is a built-in awareness and significance to social differentiation and that a more formal level of language use is available. Native speakers of English may have difficulty in learning how to use the different forms of address in French, or as they exist in other languages such as German or Spanish. Speakers of American English, in particular, are inclined towards informal modes of address, moving to a first-name basis as soon as possible. Using informal addresses inappropriately can cause considerable social friction. It takes a good deal of language socialization to acquire this kind of pragmatic ability, that is to say, sufficient exposure to the forms being used correctly. In cultures where these distinctions exist, they provide a valuable device for maintaining social distance when desired, for clearly distinguishing friends from acquaintances, and for preserving social harmony in institutional settings.

Accents and Dialects

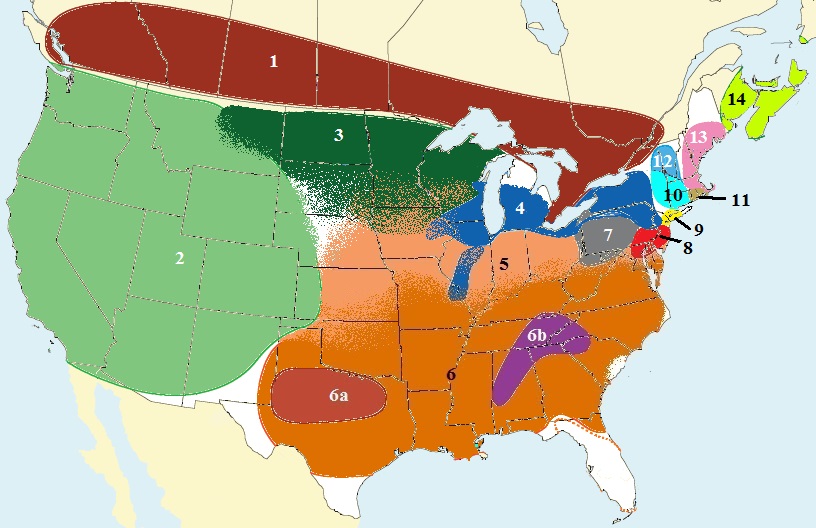

The documentary American Tongues, although dated at this point, is still a fascinating look at the rich tapestry of accents and dialects that makes up American English. Dialects are versions of languages that have distinct words, grammar, and pronunciation. Accents are distinct styles of pronunciation (Lustig & Koester, 2006). There can be multiple accents within one dialect. For example, people in the Appalachian Mountains of the eastern United States speak a dialect of American English that is characterized by remnants of the linguistic styles of Europeans who settled the area a couple of hundred years earlier. Even though they speak a similar dialect, a person in Kentucky could still have an accent that is distinguishable from a person in western North Carolina.

Dialects and accents can vary by region, class, or ancestry, and they influence the impressions that we make of others. Research shows that people tend to think more positively about others who speak with a dialect similar to their own and think more negatively about people who speak differently. Of course, many people think they speak normally and perceive others to have an accent or dialect. Although dialects include the use of different words and phrases, it’s the tone of voice that often creates the strongest impression. For example, a person who speaks with a Southern accent may perceive a New Englander’s accent to be grating, harsh, or rude because the pitch is more nasal and the rate faster. Conversely, a New Englander may perceive a Southerner’s accent to be syrupy and slow, leading to an impression that the person speaking is uneducated.

Customs and Norms

Social norms are culturally relative. The words used in politeness rituals in one culture can mean something completely different in another. For example, thank you in American English acknowledges receiving something (a gift, a favor, a compliment), in British English it can mean “yes” similar to American English’s yes, please, and in French merci can mean “no” as in “no, thank you” (Crystal, 2005). Additionally, what is considered a powerful language style varies from culture to culture. Confrontational language, such as swearing, can be seen as powerful in Western cultures, even though it violates some language taboos, but it would be seen as immature and weak in Japan (Wetzel, 1988).

Communication style refers to both verbal and nonverbal communication along with language. Problems sometimes arise when people from different cultures try to communicate using their own cultural customs and norms while ignoring other cultures’ customs and norms. An understanding of communication style differences helps listeners understand how to interpret verbal messages.

Below are a few examples of differing communication styles:

- High Context cultures, such as China, Japan, and South Korea, are those in which people assume that others within their culture will share their viewpoints and thus understand situations in much the same way. Consequently, people in such cultures often talk indirectly, using hints or suggestions to convey meaning with the thought that others will know what is being expressed. In high-context cultures, what is not said is just as important, if not more important, than what is said. High context cultures are very often collectivistic as well.

- Low context cultures on the other hand, are those in which people do NOT presume that others share their beliefs, values, and behaviors. They tend to be more verbally informative and direct in their communication (Hall & Hall, 1987). Many low context cultures are individualist, so people openly express their views and tend to make important information obvious to others.

- Direct styles are those in which verbal messages reveal the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires. The focus is on accomplishing a task. The message is clear, and to the point without hidden intentions or implied meanings. The communication tends to be impersonal. Conflict is discussed openly and people say what they think. In the United States, business correspondence is expected to be short and to the point. “What can I do for you?” is a common question when a business person receives a call from a stranger; it is an accepted way of asking the caller to state his or her business.

- Indirect styles are those in which communication is often designed to hide or minimize the speaker’s true intentions, needs, wants, and desires. Communication tends to be personal and focuses on the relationship between the speakers. The language may be subtle, and the speaker may be looking for a “softer” way to communicate there is a problem by providing many contextual cues. A hidden meaning may be embedded into the message because harmony and “saving face” is more important than truth and confrontation. In indirect cultures, such as those in Latin America, business conversations may start with discussions of the weather, or family, or topics other than business as the partners gain a sense of each other, long before the topic of business is raised.

- Elaborate styles of communication refer to the use of rich and expressive language in everyday conversation. The French, Latin Americans, Africans, and Arabs tend to use exaggerated communication because in their cultures, simple statements may be interpreted to mean the exact opposite.

- Understated communication styles value simple understatement, simple assertions, and silence. People who speak sparingly tend to be trusted more than people who speak a lot. Prudent word choice allows an individual to be socially discreet, gain social acceptance, and avoid social penalty. In Japan, the pleasure of a conversation lies “not in discussion (a logical game), but in emotional exchange” (Nakane, 1970) with the purpose of social harmony (Barnlund, 1975).

Communication Accommodation and Code-Switching

Communication accommodation theory is a theory that explores why and how people modify their communication to fit situational, social, cultural, and relational contexts (Giles, Taylor, & Bourhis, 1973). Within communication accommodation, conversational partners may use convergence, meaning a person makes their communication more like another person. People who are accommodating in their communication style are seen as more competent, which illustrates the benefits of communicative flexibility. In order to be flexible, of course, people have to be aware of and monitor their own and others’ communication patterns. Conversely, conversational partners may use divergence, meaning a person uses communication to emphasize the differences between his or her conversational partner and his or herself.

Convergence and divergence can take place within the same conversation and may be used by one or both conversational partners. Convergence functions to make others feel at ease, increase understanding, and enhance social bonds. Divergence may be used to intentionally make another person feel unwelcome or perhaps to highlight a person, group, or cultural identity.

While communication accommodation might involve anything from adjusting how fast or slow you talk to how long you speak during each turn, code-switching refers to changes in accent, dialect, or language (Martin & Nakayama, 2010). There are many reasons that people might code-switch. Regarding accents, some people hire vocal coaches or speech-language pathologists to help them alter their accents. If a Southern person thinks their accent is leading others to form unfavorable impressions, they can consciously change their accent with much practice and effort. Once their ability to speak without their Southern accent is honed, they may be able to switch very quickly between their native accent when speaking with friends and family and their modified accent when speaking in professional settings.

“Getting Critical”

Hate Speech

Hate is a term that has many different meanings and can be used to communicate teasing, mild annoyance, or anger. The term hate, as it relates to hate speech, has a much more complex and serious meaning. Hate refers to extreme negative beliefs and feelings toward a group or member of a group because of their race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or ability (Waltman & Haas, 2011). We can get a better understanding of the intensity of hate by distinguishing it from anger, which is an emotion that we experience much more regularly. First, anger is directed toward an individual, while hate is directed toward a social or cultural group. Second, anger doesn’t prevent a person from having sympathy for the target of his or her anger, but hate erases sympathy for the target. Third, anger is usually the result of personal insult or injury, but hate can exist and grow even with no direct interaction with the target. Fourth, anger isn’t an emotion that people typically find pleasure in, while hatred can create feelings of self-righteousness and superiority that lead to pleasure. Last, anger is an emotion that usually dissipates as time passes, eventually going away, while hate can endure for much longer (Waltman & Haas, 2011). Hate speech is a verbal manifestation of this intense emotional and mental state.

Hate speech is usually used by people who have a polarized view of their own group (the in-group) and another group (the out-group). Hate speech is then used to intimidate people in the out-group and to motivate and influence members of the in-group. Hate speech often promotes hate-based violence and is also used to solidify in-group identification and attract new members (Waltman & Haas, 2011). Perpetrators of hate speech often engage in totalizing, which means they define a person or a group based on one quality or characteristic, ignoring all others. A Lebanese American may be the target of hate speech because the perpetrators reduce him to a Muslim—whether he actually is Muslim or not would be irrelevant. Grouping all Middle Eastern- or Arab-looking people together is a dehumanizing activity that is typical to hate speech.

Incidents of hate speech and hate crimes have increased over the past fifteen years. Hate crimes, in particular, have gotten more attention due to the passage of more laws against hate crimes and the increased amount of tracking by various levels of law enforcement. The Internet has also made it easier for hate groups to organize and spread their hateful messages. As these changes have taken place over the past fifteen years, there has been much discussion about hate speech and its legal and constitutional implications. While hate crimes resulting in damage to a person or property are regularly prosecuted, it is sometimes argued that hate speech that doesn’t result in such damage is protected under the US Constitution’s First Amendment, which guarantees free speech. Just recently, in 2011, the Supreme Court found in the Snyder v. Phelps case that speech and actions of the members of the Westboro Baptist Church, who regularly protest the funerals of American soldiers with signs reading things like “Thank God for Dead Soldiers” and “Fag Sin = 9/11,” were protected and not criminal. Chief Justice Roberts wrote in the decision, “We cannot react to [the Snyder family’s] pain by punishing the speaker. As a nation we have chosen a different course—to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate” (Exploring Constitutional Conflicts, 2012).

Key Takeaways

- Getting integrated: Social context influences the ways in which we use language, and we have been socialized to follow implicit social rules like those that guide the flow of conversations, including how we start and end our interactions and how we change topics. The way we use language changes as we shift among academic, professional, personal, and civic contexts.

- The language that we speak influences our cultural identities and our social realities. We internalize norms and rules that help us function in our own culture but that can lead to misunderstanding when used in other cultural contexts.

- We can adapt to different cultural contexts by purposely changing our communication. Communication accommodation theory explains that people may adapt their communication to be more similar to or different from others based on various contexts.

- We should become aware of how our verbal communication reveals biases toward various cultural identities based on race, gender, age, sexual orientation, and ability.

References

American Psychological Association, “Supplemental Material: Writing Clearly and Concisely,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.apastyle.org/manual/supplement/redirects/pubman-ch03.13.aspx.

Crystal, D., How Language Works: How Babies Babble, Words Change Meaning, and Languages Live or Die (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2005), 155.

Dindia, K., “The Effect of Sex of Subject and Sex of Partner on Interruptions,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 3 (1987): 345–71.

Dindia, K. and Mike Allen, “Sex Differences in Self-Disclosure: A Meta Analysis,” Psychological Bulletin 112, no. 1 (1992): 106–24.

Exploring Constitutional Conflicts, “Regulation of Fighting Words and Hate Speech,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/hatespeech.htm.

Gentleman, A., “Indiana Call Staff Quit over Abuse on the Line,” The Guardian, May 28, 2005, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2005/may/29/india.ameliagentleman.

Giles, H., Donald M. Taylor, and Richard Bourhis, “Toward a Theory of Interpersonal Accommodation through Language: Some Canadian Data,” Language and Society 2, no. 2 (1973): 177–92.

Kwintessential Limited, “Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/cultural-services/articles/Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness.html.

Lustig, M. W. and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures, 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2006), 199–200.

Martin, J. N. and Thomas K. Nakayama, Intercultural Communication in Contexts, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 222–24.

McCornack, S., Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication (Boston, MA: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2007), 224–25.

Nadeem, S., “Accent Neutralisation and a Crisis of Identity in India’s Call Centres,” The Guardian, February 9, 2011, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/feb/09/india-call-centres-accent-neutralisation.

Pal, A., “Indian by Day, American by Night,” The Progressive, August 2004, accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.progressive.org/mag_pal0804.

Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2010), 71–76.

Southern Poverty Law Center, “Hate Map,” accessed June 7, 2012, http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/hate-map.

Varma, S., “Arbitrary? 92% of All Injuries Termed Minor,” The Times of India, June 20, 2010, accessed June 7, 2012, http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-06-20/india/28309628_1_injuries-gases-cases.

Waltman, M. and John Haas, The Communication of Hate (New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, 2011), 33.

Wetzel, P. J., “Are ‘Powerless’ Communication Strategies the Japanese Norm?” Language in Society 17, no. 4 (1988): 555–64.

Wierzbicka, A., “The English Expressions Good Boy and Good Girl and Cultural Models of Child Rearing,” Culture and Psychology 10, no. 3 (2004): 251–78.