Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between personal and social relationships.

- Describe stages of relational interaction.

- Discuss reasons for developing, maintaining, and terminating relationships

Interpersonal Relationships

In this chapter, we will examine several of our interpersonal relationships: Friendships, family, and romantic relationships. Interpersonal relationships are defined as ongoing interactions between people that involve the mutual fulfillment of needs. You may recall from chapter one that we communicate to fulfill specific needs. In this chapter, we will explore the key characteristics of our interpersonal relationships, including how different relationships fulfill differing needs.

Relationship Characteristics

Personal and Social Relationships

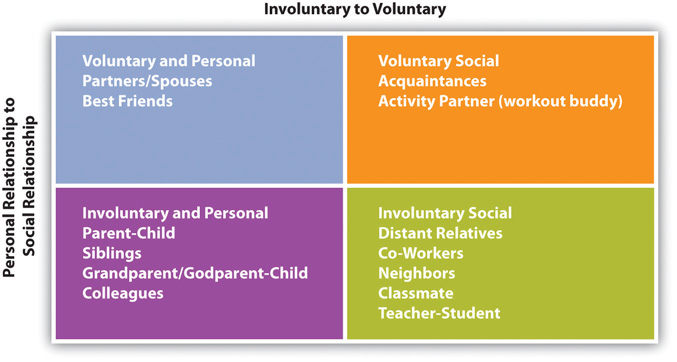

We can begin to classify key relationships we have by distinguishing between our personal and our social relationships (VanLear, Koerner, & Allen, 2006). Personal relationships meet emotional, relational, and instrumental needs, as they are intimate, close, and interdependent relationships such as those we have with best friends, partners, or immediate family. Social relationships are relationships that occasionally meet our needs and may lack the closeness and interdependence of personal relationships. Examples of social relationships include coworkers, distant relatives, and acquaintances. Another distinction useful for categorizing relationships is whether or not they are voluntary. For example, some personal relationships are voluntary, like those with romantic partners, and some are involuntary, like those with close siblings. Likewise, some social relationships are voluntary, like those with acquaintances, and some are involuntary, like those with co-workers, neighbors, or distant relatives. You can see how various relationships fall into each of these dimensions in the figure below “Types of Relationships”.

Types of Relationships

Now that we have a better understanding of how we define relationships, we’ll examine the stages that most of our relationships go through as they move from formation to termination.

Stages of Relational Development

Communication is at the heart of forming our interpersonal relationships. We reach the achievement of relating through the everyday conversations and otherwise trivial interactions that form the fabric of our relationships. It is through our communication that we adapt to the dynamic nature of our relational worlds, given that relational partners do not enter each encounter or relationship with compatible expectations. Communication allows us to test and be tested by our potential and current relational partners. It is also through communication that we respond when someone violates or fails to meet those expectations (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009).

There are ten established stages of relationship development that can help us understand how relationships come together and come apart (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). We will discuss each stage in more detail, but in the table below “Relationship Stages,” you will find a list of the communication stages. We should keep the following things in mind about this model of relationship development: relational partners do not always go through the stages sequentially, some relationships do not experience all the stages, we do not always consciously move between stages, and coming together and coming apart are not inherently good or bad. As we have already discussed, relationships are always changing—they are dynamic. Although this model has been applied most often to romantic relationships in research, most other relationships follow a similar pattern that may be adapted to a particular context. As you read the stages, think about your friendships, romantic partners, or even some family members.

Relationship Stags

| Process | Stage | Representative Communication |

|---|---|---|

| Coming Together | Initiating | “My name’s Rich. It’s nice to meet you.” |

| Experimenting | “I like to cook and refinish furniture in my spare time. What about you?” | |

| Intensifying | “I feel like we’ve gotten a lot closer over the past couple of months.” | |

| Integrating | (To friend) “We just opened a joint bank account.” | |

| Bonding | “I can’t wait to tell my parents that we decided to get married!” | |

| Coming Apart | Differentiating | “I’d really like to be able to hang out with my friends sometimes.” |

| Circumscribing | “Don’t worry about problems I’m having at work. I can deal with it.” | |

| Stagnating | (To self) “I don’t know why I even asked him to go out to dinner. He never wants to go out and have a good time.” | |

| Avoiding | “I have a lot going on right now, so I probably won’t be home as much.” | |

| Terminating | “It’s important for us both to have some time apart. I know you’ll be fine.” |

Source: Adapted from Mark L. Knapp and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 34.

Initiating

In the initiating stage, people size each other up and try to present themselves favorably. Whether you run into someone in the hallway at school or in the produce section at the grocery store, you scan the person and consider any previous knowledge you have of them, expectations for the situation, and so on. Initiating is influenced by several factors.

If you encounter a stranger, you may say, “Hi, my name’s Rich.” If you encounter a person you already know, you’ve already gone through this before, so you may just say, “What’s up?” Time constraints also affect initiation. A quick passing calls for a quick hello, while a scheduled meeting may entail a more formal start. If you already know the person, the length of time that’s passed since your last encounter will affect your initiation. For example, if you see a friend from high school while home for winter break, you may set aside a long block of time to catch up; however, if you see someone at work that you just spoke to ten minutes earlier, you may skip initiating communication. The setting also affects how we initiate conversations, as we communicate differently at a crowded bar than we do on an airplane. Even with all this variation, people typically follow typical social scripts for interaction at this stage.

Experimenting

The scholars who developed these relational stages have likened the experimenting stage, where people exchange information and often move from strangers to acquaintances, to the “sniffing ritual” of animals (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). A basic exchange of information is typical as the experimenting stage begins. For example, on the first day of class, you may chat with the person sitting beside you and take turns sharing your year in school, hometown, residence hall, and major. Then you may branch out and see if there are any common interests that emerge. Finding out you’re both St. Louis Cardinals fans could then lead to more conversation about baseball and other hobbies or interests; however, sometimes the experiment may fail. If your attempts at information exchange with another person during the experimenting stage are met with silence or hesitation, you may interpret their lack of communication as a sign that you shouldn’t pursue future interaction.

Experimenting continues in established relationships. Small talk, a hallmark of the experimenting stage, is common among young adults catching up with their parents when they return home for a visit or committed couples when they recount their day while preparing dinner. Small talk can be annoying sometimes, especially if you feel like you have to do it out of politeness. However, small talk serves important functions, such as creating a communicative entry point that can lead people to uncover topics of conversation that go beyond the surface level, helping us audition someone to see if we’d like to talk to them further, and generally creating a sense of ease and community with others. And even though small talk isn’t viewed as very substantive, the authors of this model of relationships indicate that most of our relationships do not progress far beyond this point (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009).

Intensifying

As we enter the intensifying stage, we indicate that we would like or are open to more intimacy, and then we wait for a signal of acceptance before we attempt more intimacy. This incremental intensification of intimacy can occur over a period of days, weeks, months, or years and may involve inviting a new friend to join you at a party, then to your place for dinner, then to go on vacation with you. It may be seen as odd, even if the experimenting stage went well, to invite a person who you’re still getting to know on vacation with you without engaging in some less intimate interaction beforehand. In order to save face and avoid making ourselves overly vulnerable, steady progression is typically key in this stage. Aside from sharing more intense personal time, requests for and granting favors may also play into intensification of a relationship. For example, one friend helping the other prepare for a big party on their birthday can increase closeness. However, if one person asks for too many favors or fails to reciprocate favors granted, then the relationship can become unbalanced, which could result in a transition to another stage, such as differentiating.

Other signs of the intensifying stage include the creation of nicknames, inside jokes, and personal idioms; increased use of we and our; increased communication about each other’s identities (e.g., “My friends all think you are really laid back and easy to get along with”); and a loosening of typical restrictions on possessions and personal space (e.g., you have a key to your best friend’s apartment and can hang out there if your roommate is getting on your nerves). Navigating the changing boundaries between individuals in this stage can be tricky, which can lead to conflict or uncertainty about the relationship’s future as new expectations for relationships develop. Successfully managing this increasing closeness can lead to relational integration.

Integrating

In the integrating stage, two people’s identities and personalities merge, and a sense of interdependence develops. Even though this stage is most evident in romantic relationships, there are elements that appear in other relationship forms. Some verbal and nonverbal signals of the integrating stage are when the social networks of two people merge; those outside the relationship begin to refer to or treat the relational partners as if they were one person (e.g., always referring to them together—“Let’s invite Olaf and Bettina”); or the relational partners present themselves as one unit (e.g., both signing and sending one holiday card or opening a joint bank account). Even as two people integrate, they likely maintain some sense of self by spending time with friends and family separately, which helps balance their needs for independence and connection.

Bonding

The bonding stage includes making a public announcement to the world about their formal commitment. Bonding rituals can include weddings, commitment ceremonies, and civil unions. Obviously, this stage is applicable to romantic couples. However, friends may decide to move in together as a formal commitment to their relationship. In some ways, the bonding ritual is arbitrary, in that it can occur at any stage in a relationship. In fact, bonding rituals are often later annulled or reversed because a relationship doesn’t work out, perhaps because there wasn’t sufficient time spent in the experimenting or integrating phases. However, bonding warrants its own stage because the symbolic act of bonding can have very real effects on how two people communicate about and perceive their relationship. For example, the formality of the bond may lead the couple and those in their social network to more diligently maintain the relationship if conflict or stress threatens it.

Differentiating

Individual differences can present a challenge at any given stage in the relational interaction model; however, in the differentiating stage, communicating these differences becomes a primary focus. Differentiating is the reverse of integrating, as we and our reverts back to I and my. People may try to reboundary some of their life prior to the integration of the current relationship, including other relationships or possessions. For example, Carrie may reclaim friends who became “shared” as she got closer to her roommate Julie and their social networks merged by saying, “I’m having my friends over to the apartment and would like to have privacy for the evening.” Differentiating may onset in a relationship that bonded before the individuals knew each other in enough depth and breadth. Even in relationships where the bonding stage is less likely to be experienced unpleasant discoveries about the other person’s past, personality, or values during the integrating or experimenting stage could lead a person to begin differentiating. Many relationships experience differentiating throughout the duration of the relationship. It is not necessarily a bad thing.

Circumscribing

To circumscribe means to draw a line around something or put a boundary around it (Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2011). So in the circumscribing stage, communication decreases and certain areas or subjects become restricted as individuals verbally close themselves off from each other. They may say things like “I don’t want to talk about that anymore” or “You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.” If one person was more interested in differentiating in the previous stage, or the desire to end the relationship is one-sided, verbal expressions of commitment may go unechoed—for example, when one person’s statement, “I know we’ve had some problems lately, but I still like being with you,” is met with silence. Passive-aggressive behavior and withdrawal may occur more frequently in this stage. Once the increase in boundaries and decrease in communication becomes a pattern, the relationship further deteriorates toward stagnation.

Stagnating

During the stagnating stage, the relationship may come to a standstill, as individuals basically wait for the relationship to end. Outward communication may be avoided, but internal communication may be frequent. The relational conflict flaw of mindreading takes place as a person’s internal thoughts lead them to avoid communication. For example, a person may think, “There’s no need to bring this up again because I know exactly how they’ll react!” This stage can be prolonged in some relationships. Parents and children who are estranged, couples who are separated and awaiting a divorce, or friends who want to end a relationship but don’t know how to do it may have extended periods of stagnation. Short periods of stagnation may occur right after a failed exchange in the experimental stage, where you may be in a situation that’s not easy to get out of, but the person is still there. Although most people don’t like to linger in this unpleasant stage, some may do so to avoid potential pain from termination, some may still hope to rekindle the spark that started the relationship, or some may enjoy leading their relational partner on.

Avoiding

Moving to the avoiding stage may be a way to end the awkwardness that comes with stagnation, as people signal that they want to close down the lines of communication. Communication in the avoiding stage can be very direct—“I don’t want to talk to you anymore”—or more indirect—“I have to meet someone in a little while, so I can’t talk long.” While physical avoidance such as leaving a room or requesting a schedule change at work may help clearly communicate the desire to terminate the relationship, we don’t always have that option. In a parent-child relationship, where the child is still dependent on the parent, or in a roommate situation, where a lease agreement prevents leaving, people may engage in cognitive dissociation, which means they mentally shut down and ignore the other person even though they are still physically copresent.

Terminating

The terminating stage of a relationship can occur shortly after initiation or after a ten- or twenty-year relational history has been established. Termination can result from outside circumstances such as geographic separation or internal factors such as changing values or personalities that lead to a weakening of the bond. Termination exchanges involve some typical communicative elements and may begin with a summary message that recaps the relationship and provides a reason for the termination (e.g., “We’ve had some ups and downs over our three years together, but I’m getting ready to go to college, and I either want to be with someone who is willing to support me, or I want to be free to explore who I am.”). The summary message may be followed by a distance message that further communicates the relational drift that has occurred (e.g., “We’ve really grown apart over the past year”), which may be followed by a disassociation message that prepares people to be apart by projecting what happens after the relationship ends (e.g., “I know you’ll do fine without me. You can use this time to explore your options and figure out if you want to go to college too or not.”). Finally, there is often a message regarding the possibility for future communication in the relationship (e.g., “I think it would be best if we don’t see each other for the first few months, but text me if you want to.”) (Knapp & Vangelisti, 2009). These ten stages of relational development provide insight into the complicated processes that affect relational formation and deterioration. We also make decisions about our relationships by weighing costs and rewards.

Relationship Repair

Relationships in the differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, and avoiding stages do not always end in termination. Once a relationship begins to deteriorate, the relational partners may decide to engage in relationship repair. Repair happens both intrapersonally and interpersonally.

Intrapersonal repair happens individually and includes:

- recognizing the relationship needs repair

- engaging in productive communication

- proposing possible solutions

- self-affirmation

- acknowledging risks – take a chance and make the first move

- integrating solutions into your everyday behaviors even though the other partner may not do so (at least initially).

Interpersonal repair happens as a dyad and includes:

- recognize the problem(s)

- participate in productive conflict resolution

- propose possible solutions

- affirm each other during the process

- integrate solutions into their everyday behavior

- acknowledge the risks involved.

Reasons for Relationship Initiation, Maintenance, and Termination

Attraction

Have you ever wondered why people pick certain relationships over others? We can’t pick our family members, although I know some people wish they could. We can, however, select who our friends and significant others are in our lives. Throughout our lives, we pick and select people that we build a connection to and have an attraction towards. We tend to avoid certain people who we don’t find attractive.

Similarities and Differences

Disclosure

Social Exchange

Social exchange theory essentially entails a weighing of the costs and rewards in a given relationship (Harvey & Wenzel, 2006). Rewards are outcomes that we get from a relationship that benefit us in some way, while costs can range from granting favors to providing emotional support. Rewards could be tangible (e.g., food, money, clothes) or intangible (support, admiration, status). Costs may be undesirable things that we don’t want to expend a lot of energy to do. For instance, we don’t want to have to constantly nag the other person to call us or spend a lot of time arguing about past items. Often, when people decide to stay or leave a relationship, they will consider the costs and rewards in the relationship. When we do not receive the outcomes or rewards that we think we deserve, then we may negatively evaluate the relationship, or at least a given exchange or moment in the relationship, and view ourselves as being under benefited. In an equitable relationship, costs and rewards are balanced, which usually leads to a positive evaluation of the relationship and satisfaction.

Commitment and interdependence are important interpersonal and psychological dimensions of a relationship that relate to social exchange theory. Interdependence refers to the relationship between a person’s well-being and involvement in a particular relationship. A person will feel interdependence in a relationship when (1) satisfaction is high or the relationship meets important needs; (2) the alternatives are not good, meaning the person’s needs couldn’t be met without the relationship; or (3) investment in the relationship is high, meaning that resources might decrease or be lost without the relationship (Harvey & Wenzel, 2006).

We can be cautioned, though, to not view social exchange theory as a tit-for-tat accounting of costs and rewards (Noller, 2006). First, not everyone will perceive costs and rewards the same. What may be a cost to one person may not be perceived as a cost to another. Second, we wouldn’t be very good relational partners if we carried around a little notepad, notating each favor or good deed we completed so we can expect its repayment. We may become aware of the balance of costs and rewards at some point in our relationships, but that awareness isn’t persistent because relationships are dynamic. We also have communal relationships, in which members engage in a relationship for mutual benefit and do not expect returns on investments such as favors or good deeds (Harvey & Wenzel, 2006). As the dynamics in a relationship change, we may engage communally without even being aware of it, just by simply enjoying the relationship. It has been suggested that we become more aware of the costs and rewards balance when a relationship is going through conflict (Noller, 2006). Overall, relationships are more likely to succeed when there is satisfaction and commitment, meaning that we are pleased in a relationship intrinsically or by the rewards we receive.

Equity

Equity theory (Adams, 1965) was developed to understand workplace relationships. Adams (1965) asserted that we develop and maintain relationships when the ratio of the rewards and costs is equal to that of our partners. This is similar to the Social Exchange theory because it is an economic model. However, it differs in that it acknowledges that cultural values and ideologies influence the decisions we make. The keywords here are equal relationships. In relationships, we want to perceive ourselves to be equally satisfied.

For example, a couple might share workloads equally or split the household expenses equally because doing so satisfies them at the same level. Or, one person may contribute more to housework while the other contributes more to financial support. Either way, if the perception is that costs and rewards are equal, the couple is usually satisfied. However, if the balance tips in favor of one over the other, problems may arise. Adams’ theory relies on the notion that people value fair treatment and are motivated by it. It is a perceptual theory in that it is the “perceived” equality that makes the difference. If one partner in the previous example perceives that one person is not paying their fair share of the expenses, the relationship can deteriorate.

Key Takeaways

-

Relationships can be easily distinguished into personal or social and voluntary or involuntary.

- There are stages of relational interaction in which relationships come together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, and bonding) and come apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, and terminating).

- There are many reasons we initiate, develop, maintain, and terminate relationships.

References

Harvey, J. H. and Amy Wenzel, “Theoretical Perspectives in the Study of Close Relationships,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 38–39.

Knapp, M. L. and Anita L. Vangelisti, Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships (Boston, MA: Pearson, 2009), 32–51.

Noller, P., “Bringing It All Together: A Theoretical Approach,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 770.

Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed September 13, 2011, http://www.oed.com.

Perman, C., “Bad Economy? A Good Time for a Steamy Affair,” USA Today, September 8, 2011, accessed September 13, 2011, http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/story/2011-09-10/economy-affairs-divorce-marriage/50340948/1.

VanLear, C. A., Ascan Koerner, and Donna M. Allen, “Relationship Typologies,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, eds. Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 95.