Learning Objectives

- Discuss the influences on attraction and romantic partner selection.

- Discuss the differences between passionate, companionate, and romantic love.

- Explain how social networks affect romantic relationships.

- Explain how sexual orientation and race and ethnicity affect romantic relationships.

Romance has swept humans off their feet for hundreds of years, as is evidenced by countless odes written by love-struck poets, romance novels, and reality television shows like The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. Whether pining for love in the pages of a diary or trying to find a soul mate from a cast of suitors, love and romance can seem to take us over at times. As we have learned, communication is the primary means by which we form, maintain, and end our relationships. In this section, we will explore the communicative aspects of romantic relationships including love, sex, social networks, and cultural influences.

Relationship Formation and Maintenance

Much of the research on romantic relationships distinguishes between premarital and marital couples. However, given the changes in marriage and the diversification of recognized ways to couple, we will use the distinctions: dating, cohabitating, and partnered couples. The category for dating couples encompasses the courtship period, which may range from a first date through several years. If a couple moves in together, they fit into the category of cohabitating couple. Partnered couples take additional steps to verbally, ceremonially, or legally claim their intentions to be together in a long-term committed relationship. The romantic relationships people have before they become partnered provide important foundations for later relationships. But how do we choose our romantic partners, and what communication patterns affect how these relationships come together and apart?

Family background, values, physical attractiveness, and communication styles are just some of the factors that influence our selection of romantic relationships (Segrin & Flora, 2005). Attachment theory relates to the bond that a child feels with their primary caregiver. Research has shown that the attachment style (secure, anxious, or avoidant) formed as a child influences adult romantic relationships. Other research shows that adolescents who feel like they have a reliable relationship with their parents feel more connection and attraction in their adult romantic relationships (Seiffge-Krenke, Shulman, & Kiessinger, 2001). Aside from attachment, which stems more from individual experiences as a child, relationship values, which stem more from societal expectations and norms, also affect romantic attraction.

We can see the important influence that communication has on the way we perceive relationships by examining the ways in which relational values have changed over recent decades. Over the course of the twentieth century, for example, the preference for chastity as a valued part of relationship selection decreased significantly. While people used to indicate that it was very important that the person they partner with not have had any previous sexual partners, today people list several characteristics they view as more important in mate selection (Segrin & Flora, 2005). In addition, characteristics like income and cooking/housekeeping skills were once more highly rated as qualities in a potential mate. More recently, mutual attraction and love are the top mate-selection values.

“Getting Critical”

Arranged Marriages

Although romantic love is considered a precursor to marriage in Western societies, this is not the case in other cultures. As was noted earlier, mutual attraction and love are the most important factors in mate selection in research conducted in the United States. In some other countries, like China, India, and Iran, mate selection is primarily decided by family members and may be based on the evaluation of a potential partner’s health, financial assets, social status, or family connections. In some cases, families make financial arrangements to ensure the marriage takes place. Research on marital satisfaction of people in autonomous (self-chosen) marriages and arranged marriages has been mixed, but a recent study found that there was no significant difference in marital satisfaction between individuals in marriages of choice in the United States and those in arranged marriages in India (Myers, Madathil, & Tingle, 2005). While many people undoubtedly question whether a person can be happy in an arranged marriage, in more collectivistic (group-oriented) societies, accommodating family wishes may be more important than individual preferences. Rather than love leading up to a marriage, love is expected to grow as partners learn more about each other and adjust to their new lives together once married.

- Do you think arranged marriages are ethical? Why or why not?

- Try to step back and view both types of marriages from an outsider’s perspective. The differences between the two types of marriage are fairly clear, but in what ways are marriages of choice and arranged marriages similar?

- List potential benefits and drawbacks of marriages of choice and arranged marriages.

Love and Sexuality in Romantic Relationships

When most of us think of romantic relationships, we think about love. However, love did not need to be a part of a relationship for it to lead to marriage until recently. In fact, marriages in some cultures are still arranged based on pedigree (family history) or potential gain in money or power for the couple’s families. Today, love often doesn’t lead directly to a partnership, given that most people don’t partner with their first love. Love, like all emotions, varies in intensity and is an important part of our interpersonal communication.

To better understand love, we can make a distinction between passionate love and companionate love (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2000). Passionate love entails an emotionally charged engagement between two people that can be both exhilarating and painful. For example, the thrill of falling for someone can be exhilarating, but feelings of vulnerability or anxiety that the love may not be reciprocated can be painful. Companionate love is affection felt between two people whose lives are interdependent. For example, romantic partners may come to find a stable and consistent love in their shared time and activities together. The main idea behind this distinction is that relationships that are based primarily on passionate love will terminate unless the passion cools overtime into a more enduring and stable companionate love. This doesn’t mean that passion must completely die out for a relationship to be successful long term. In fact, a lack of passion could lead to boredom or dissatisfaction. Instead, many people enjoy the thrill of occasional passion in their relationship but may take solace in the security of a love that is more stable. While companionate love can also exist in close relationships with friends and family members, passionate love is often tied to sexuality present in romantic relationships.

There are many ways in which sexuality relates to romantic relationships and many opinions about the role that sexuality should play in relationships, but this discussion focuses on the role of sexuality in attraction and relational satisfaction. Compatibility in terms of sexual history and attitudes toward sexuality are more important predictors of relationship formation. For example, if a person finds out that a romantic interest has had a more extensive sexual history than their own, they may not feel compatible, which could lessen attraction (Sprecher & Regan, 2000). Once together, considerable research suggests that a couple’s sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction are linked such that sexually satisfied individuals report a higher quality relationship, including more love for their partner and more security in the future success of their relationship (Sprecher & Regan, 2000). While sexual activity often strengthens emotional bonds between romantic couples, it is clear that romantic emotional bonds can form in the absence of sexual activity and sexual activity is not the sole predictor of relational satisfaction. In fact, sexual communication may play just as important a role as sexual activity. Sexual communication deals with the initiation or refusal of sexual activity and communication about sexual likes and dislikes (Sprecher & Regan, 2000). For example, a sexual communication could involve a couple discussing a decision to abstain from sexual activity until a certain level of closeness or relational milestone (like marriage) has been reached. Sexual communication could also involve talking about sexual likes and dislikes. Sexual conflict can result when couples disagree over frequency or type of sexual activities. Sexual conflict can also result from jealousy if one person believes their partner is focusing sexual thoughts or activities outside of the relationship. While we will discuss jealousy and cheating more in the section on the dark side of relationships, it is clear that love and sexuality play important roles in our romantic relationships.

Romantic Relationships and Social Networks

Social networks influence all our relationships but have gotten special attention in research on romantic relations. Romantic relationships are not separate from other interpersonal connections to friends and family. Is it better for a couple to share friends, have their own friends, or attempt a balance between the two? Overall, research shows that shared social networks are one of the strongest predictors of whether or not a relationship will continue or terminate.

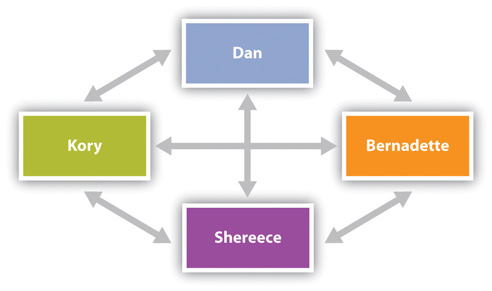

Network overlap refers to the number of shared associations, including friends and family, that a couple has (Milardo & Helms-Erikson, 2000). For example, if Dan and Shereece are both close with Dan’s sister Bernadette, and all three of them are friends with Kory, then those relationships completely overlap.

Social Network Overlap

Network overlap creates some structural and interpersonal elements that affect relational outcomes. Friends and family who are invested in both relational partners may be more likely to support the couple when one or both parties need it. In general, having more points of connection to provide instrumental support through the granting of favors or emotional support in the form of empathetic listening and validation during times of conflict can help a couple manage common stressors of relationships that may otherwise lead a partnership to deteriorate (Milardo & Helms-Erikson, 2000).

In addition to providing a supporting structure, shared associations can also help create and sustain a positive relational culture. For example, mutual friends of a couple may validate the relationship by discussing the partners as a “couple” or “pair” and communicate their approval of the relationship to the couple separately or together, which creates and maintains a connection (Milardo & Helms-Erikson, 2000). Being in the company of mutual friends also creates positive feelings between the couple, as their attention is taken away from the mundane tasks of work and family life. Imagine Dan and Shereece host a board-game night with a few mutual friends in which Dan wows the crowd with charades, and Kory says to Shereece, “Wow, he’s really on tonight. It’s so fun to hang out with you two.” That comment may refocus attention onto the mutually attractive qualities of the pair and validate their continued interdependence.

“Getting Plugged In”

Online Dating

It is becoming more common for people to initiate romantic relationships through the Internet, and online dating sites are big business, bringing in $470 million a year (Madden & Lenhart, 2006). Whether it’s through sites like Match.com or OkCupid.com or through chat rooms or social networking, people are taking advantage of some of the conveniences of online dating. But what are the drawbacks?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of online dating?

- What advice would you give a friend who is considering using online dating to help him or her be a more competent communicator?

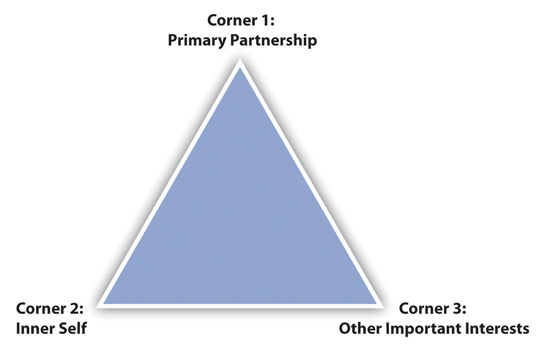

Interdependence and relationship networks can also be illustrated through the theory of triangles (see below) which examines the relationship between three domains of activity: the primary partnership (corner 1), the inner self (corner 2), and important outside interests (corner 3) (Marks, 1986).

Theory of Triangles

All of the corners interact with each other, but it is the third corner that connects the primary partnership to an extended network. For example, the inner self (corner 2) is enriched by the primary partnership (corner 1) but also gains from associations that provide support or a chance for shared activities or recreation (corner 3) that help affirm a person’s self-concept or identity. Additionally, the primary partnership (corner 1) is enriched by the third-corner associations that may fill gaps not met by the partnership. When those gaps are filled, a partner may be less likely to focus on what they’re missing in their primary relationship. However, the third corner can also produce tension in a relationship if, for example, the other person in a primary partnership feels like they are competing with their partner’s third-corner relationships. During times of conflict, one or both partners may increase their involvement in their third corner, which may have positive or negative effects. A strong romantic relationship is good, but research shows that even when couples are happily married they reported loneliness if they were not connected to friends. While the dynamics among the three corners change throughout a relationship, they are all important.

Dating Relationships

We talk of dating as a single construct a lot of the time without really thinking through how dating has changed over time. In the 20th Century alone, we saw dating go from a highly formalized structure involving calling cards and sitting rooms and dinner dates; to more casual structures like movies and coffee; to cyberdating with people we’ve never met. The 21st Century has already changed how people date through social networking sites and geolocation dating apps on smartphones.

.

.

.

.

Dating has changed with the times. Dating – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

So, with all of this change, how does one even begin to know if someone’s on a date in the first place? Thankfully Paul Mongeau, Janet Jacobsen, and Carolyn Donnerstein have attempted to answer this question for us. The researchers found that there are five of what they called “supracategories” that help define the term “date”: communication expectations, date goals, date elements, dyadic, and feelings. First, dating involves specific communication expectations. For example, people expect that there will be a certain level of self-disclosure on a date. Furthermore, people expect that their dating partner will be polite, relaxed, and social. Second, dating involves specific date goals, or people on dates have specific goals (e.g., future romantic relationships, reduce uncertainty, have fun). Third, there are specific date elements. For example, someone has to initiate the date; we get ready for a date, we know when the date has started and stopped, there are activities that constitute the date, etc. Fourth, dates are dyadic, or dating is a couple-based activity. Now, this doesn’t necessarily take into account the idea of “group dates,” but even on a group date traditionally there are dyadic couples that are involved in the date itself. Lastly, dates involve feelings. “These feelings range from affection (nonromantic feelings or behaviors), attraction (physical and/or emotional attraction toward the partner), to romantic (dates have romantic overtones).” 29

Dating Scripts

All of us are going to spend a portion of our lives in some kind of dating relationship. Whether we are initiating dates, dating, or terminating relationships, we spend a great deal of time dating. Match.com publishes an annual study examining singles in the United States (https://www.singlesinamerica.com/). According to data from 2018, here are some of the realities of modern single life:

• 55.8% did not go on any first dates, while only 12.6% went on one first date.

• Of those who went on a first date, 20.3% met the person on an online dating site/app while 15.6% met the person through a friend.

• When it comes to being passionately in love, 19.4% have never been in love, 27.3% have been in love once, and 27.7% have been in love twice.

• 25.1% have a “checklist” when it comes to finding a long-term romantic partner.

• 66.7% believe that loving someone is hard work.

• 75.2% believe that love is a possibility for them.

• 83.5% believe that love is hard to find in today’s world.

• 32.4% of dating partners have disagreed on how to label their relationship, and 23.0% have left a relationship over this disagreement.

• When it comes to first dates, participants preferred either quick and easy (36.0%, e.g., coffee, drinks) or more formal (21%, e.g., dinner, brunch).

• 38.1% had been in a “friends with benefits” relationship.

• 28.3% had a friendship that turned into a significant romantic relationship.

• 41.1% have dated someone they met online.

• 48.9% had created at least one profile on a dating website or app.

Admittedly, this study is probably pretty heterosexist because the data were not broken down by sexual orientation. Furthermore, we don’t have similar data for bisexual, gay, and lesbian couples. Dating is one of those things we will spend a lot of time doing before we ever settle down and get married (assuming you ever do or have a desire to do so). So, one must imagine that with so much dating going on in the world, we’d have a pretty good grasp of how dating works.

Robert Abelson originally proposed the idea of script theory back in the late 1970s. He defined a script as a “coherent sequence of events expected by the individual, involving him as either a participant or an observer” (Abelson, 1970). According to script theory, people tend to pattern their responses and behaviors during different social interactions to take control of that situation. This does require an individual to be able to imagine their past, present, and future behavior to create this script. In 1993, Suzanna Rose and Irene Frieze applied Abelson’s notions of script theory to dating. They had college students keep records of what they did on a date. Ultimately, two different scripts were derived: one for men and one for women. The male script consisted of 15 different behavioral actions (all initiated by the male):

1. Picked up date

2. Met parents/roommates

3. Left

4. Picked up friends

5. Confirmed plans

6. Talked, joked, laughed

7. Went to movies, show, party

8. Ate

9. Drank alcohol

10. Initiated sexual contact

11. Made out

12. Took date home

13. Asked for another date

14. Kissed goodnight

15. Went home

Women’s scripts, on the other hand, contained both behavioral actions for themselves and behavioral

actions they expected of the man during the date:

1. Groomed and dressed

2. Was nervous

3. Picked up date (male)

4. Introduced to parents, etc.

5. Courtly behavior (open doors–male)

6. Left

7. Confirmed plans

8. Got to know & evaluate date

9. Talked, joked, laughed

10. Enjoyed date

11. Went to movies, show, party

12. Ate

13. Drank alcohol

14. Talked to friends

15. Had something go wrong

16. Took date home (male)

17. Asked for another date (male)

18. Told date will call her (male)

19. Kissed date goodnight (male)

Take a second and go through these two lists. Do you think they still apply today? How do you think these scripts differ? Once again, these dating scripts were created only using heterosexual college students. Do you think these scripts change with homosexual or bi-sexual couples? What about with differing cultures? Or if you have people dating in their late 20s or 30s? What about people who date in their 70s, 80s, or 90s?

There has been subsequent research in the area of dating scripts. Table 8.1 demonstrates some of the other dating scripts that researchers have found (this is not an exhaustive list).

| First Date36 | Gay Men37 | Lesbians38 | Deaf College Students39 |

|

|

|

|

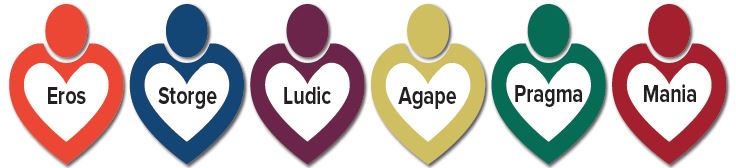

An individual’s love style is considered to be an attitude and describes how love is perceived (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1988). Attitudes toward love and perceptions of love may change throughout an individual’s life. College students may perceive love very differently from their parents or guardians because college students are in a very different stage of life. College students are living among people their age who are more than likely single or unmarried. These two factors mean that there are more prospects for dating, and this may lead the college student to conclude that dating any number of these prospects is necessary or even perceive that “hooking up” with multiple prospects is acceptable. In contrast, individuals with children who are financially tied may view romantic relationships as partnerships in which goal achievement (pay off the house, send kids to college, pay off debt, etc.) is as important as romance. These differences in perceptions of love can be explored through John Lee’s love typology in which he discusses six love styles: eros, storge, ludus, agape, pragma, and mania (Figure 8.3) (Lee, 1977).

Eros

Eros is romance and emphasizes love and physical beauty, immediate attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment. Eros love involves the early initiation of sexual intimacy and consecutive monogamous relationships.

Storge

Storge love develops slowly out of friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued along with commitment, which leads to enduring love. Passion and intense emotions are not valued as they are in the eros love style. One of the author’s uncles was in his 60s and had never been married. However, he employed a woman who cooked and cleaned for him for over 20 years. His family was very surprised to receive an announcement that he was marrying the individual who took care of him for so long. The formation of their love is a great example of love that arises slowly out of friendship.

Ludic

Ludic lovers view love as a game, and playing this game with multiple partners is perceived to be acceptable by individuals with this love style. As such, this type of lover believes that deception and manipulation are acceptable. Individuals with this love style have a low tolerance for commitment, jealousy, and strong emotional attachment.

Agape

In contrast, agape love involves altruism, giving, and other-centered love. This love style approaches relationships in a non-demanding style with gentle caring and tolerance for others.

Pragma

Pragma love is known as practical love involving logic and reason. Arranged marriages were often arranged for functional purposes. Kings and Queens of different countries often married to form alliances. This love style may seek out a romantic partner for financial stability, ability to parent, or simple companionship.

Mania

Mania is the final love style characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval. This type of love is insecure and needs constant reassurance.

These love styles should not be considered to be mutually independent. An individual may approach love from a pragmatic stance and have found love that provides financial stability. However, they still feel insecure (representative of mania) about whether their romantic partner will remain with them, thus ensuring continued financial stability. It is important to remember that individuals engage in each of these love styles, and it is simply a matter of how much of each love style a person possesses.

Key Takeaways

- Romantic relationships include dating, cohabitating, and partnered couples.

- Family background, values, physical attractiveness, and communication styles influence our attraction to and selection of romantic partners.

- Passionate, companionate, and romantic love and sexuality influence relationships.

- Network overlap is an important predictor of relational satisfaction and success.

- Mongeau, Jacobsen, and Donnerstein defined the term “dating” by identifying a series of “supracategories” that help define the term: communication expectations, date goals, date elements, dyadic, and feelings.

- The idea of script theory was originally proposed by Abelson who defined the concept of scripts as sequences of events expected by a participant or an observer. Dating scripts, therefore, are patterns of behavior that are expected during a “date.”

- There are six different love styles. Eros is romance and emphasizes love and physical beauty, immediate attraction, emotional intensity, and strong commitment. Second, storge love develops slowly out of friendship where stability and psychological closeness are valued along with commitment, which leads to enduring love. Third, ludic lovers view love as a game, and playing this game with multiple partners is perceived to be acceptable by individuals with this love style. Fourth, agape love involves altruism, giving, and other-centered love. Fifth, pragma love is known as practical love involving logic and reason. Lastly, mania love is characterized by dependence, uncertainty, jealousy, and emotional upheaval.

Exercises

- In terms of romantic attraction, which adage do you think is more true and why? “Birds of a feather flock together” or “Opposites attract.”

- List some examples of how you see passionate and companionate love play out in television shows or movies. Do you think this is an accurate portrayal of how love is experienced in romantic relationships? Why or why not?

- Social network overlap affects a romantic relationship in many ways. What are some positives and negatives of network overlap?

- Compare a current or past romantic relationship to the definition of romantic

relationships provided in this chapter. What are the similarities and differences in

your romantic relationship? - List the physical features you find attractive. List the personality factors you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with someone who possessed the personality characteristics you find attractive, but not the physical characteristics? Why or why not? Now, consider whether you would have a romantic relationship with someone physically attractive, but who did not possess the personality characteristics you find attractive. Would you have a romantic relationship with this individual? Why or why not?

- List and define each love style. List the love style of each of your parents and grandparents. Explain how your love style developed and whether it was learned from a family member or innate.

References

Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (1988). Lovers wear rose colored glasses. Journal of

Social and Personal Relationships, 5, 161-183. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540758800500203

Hendrick, S. S. and Clyde Hendrick, “Romantic Love,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 204–5.

Lee, J. A. (1977). A typology of styles of loving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616727700300204

Madden, M. and Amanda Lenhart, “Online Dating,” Pew Internet and American Life Project, March 5, 2006, accessed September 13, 2011, http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2006/PIP_Online_Dating.pdf.pdf.

Marks, S. R., Three Corners: Exploring Marriage and the Self (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1986), 5.

Milardo, R. M. and Heather Helms-Erikson, “Network Overlap and Third-Party Influence in Close Relationships,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 33.

Myers, J. E., Jayamala Madathil, and Lynne R. Tingle, “Marriage Satisfaction and Wellness in India and the United States: A Preliminary Comparison of Arranged Marriages and Marriages of Choice,” Journal of Counseling and Development 83 (2005): 183–87.

Segrin, C. and Jeanne Flora, Family Communication (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2005), 106.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., Shmuel Shulman, and Nicolai Kiessinger, “Adolescent Precursors of Romantic Relationships in Young Adulthood,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 18, no. 3 (2001): 327–46.

Sprecher, S. and Pamela C. Regan, “Sexuality in a Relational Context,” in Close Relationships: A Sourcebook, eds. Clyde Hendrick and Susan S. Hendrick (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000), 217–19.

Walster, E., Vera Aronson, Darcy Abrahams, and Leon Rottman, “Importance of Physical Attractiveness in Dating Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 4, no. 5 (1966): 508–16.