1 1.4 Understanding Cultural Differences

Learning Objectives

Type your learning objectives here.

- Explain Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

- Differentiate Hall’s cultural variations.

Communication is not universal. In this section, we will look at cultural differences through the lenses of German psychologist Geert Hofstede; American anthropologist Edward Hall, and Scottish Business Professor Charles Tidwell. By gaining a basic understanding of cultural differences, we can better understand how to interact with citizens of our diverse, multicultural society.

Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture

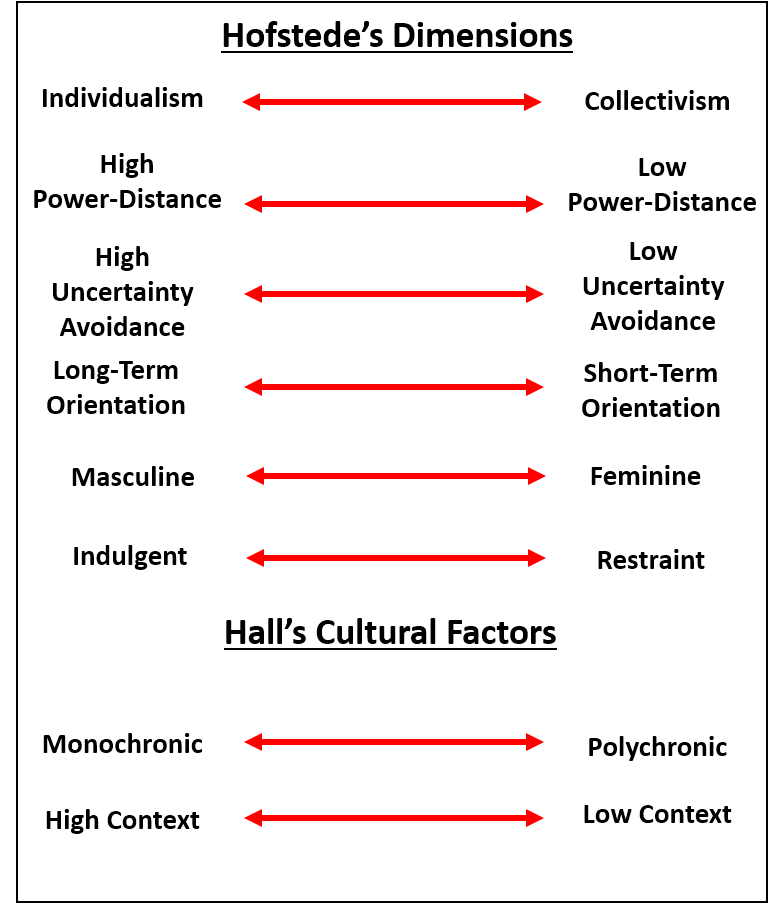

Psychologist Geert Hofstede published his cultural dimensions model at the end of the 1970s. Since then, it’s become an internationally recognized standard for understanding cultural differences. Hofstede studied people in more than 50 countries and identified six dimensions that could distinguish one culture from another. Hofstede has fine-tuned his theory of culture, and the most recent update to his theory occurred in 2010.

These six dimensions are individualism vs. collectivism, discussed in the previous section; high power distance vs. low power distance; high certainty avoidance vs. low certainly avoidance; long-term vs. short-term orientation; masculine vs. feminine; and indulgence vs. restraint. They represent preferences people have for things to be a certain way. While we all have our individual preferences, patterns emerge within cultures that help us to understand important differences in the way we interact.

Individualism and Collectivism

In an individualistic culture, there is a belief that you can do what you want and follow your passions. In an individualistic culture, if someone asked what you do for a living, they would answer by saying their profession or occupation. However, in collectivistic cultures, a person would answer in terms of the group, organization, and/or corporation they serve. Moreover, in a collectivistic culture, there is a belief that you should do what benefits the group. In other words, collectivistic cultures focus on how the group can grow and be productive.

Put simply, you can think of an individualistic culture as a culture where members make choices based on personal preference. They can pursue their own wants and needs without concerns about meeting social expectations. The United States is a highly individualistic culture. While we value the role of certain aspects of collectivism, such as government and social organizations, at our core, we strongly believe it is up to each person to find and follow his or her path in life.

In a highly collectivistic culture, just the opposite is true. It is the role of individuals to fulfill their place in the overall social order. Personal wants and needs are secondary to the needs of society at large. There is immense pressure to adhere to social norms, and those who fail to conform risk social isolation, disconnection from family, and perhaps some form of banishment. China is typically considered a highly collectivistic culture. In China, multigenerational homes are common, and tradition calls for the oldest son to care for his parents as they age.

High Power-Distance and Low Power-Distance

Power is a normal feature of any society. How power is perceived, however, varies among cultures. In high power-distance cultures, the members accept some having more power and some having less power and accept that this power distribution is natural and normal. Those with power are assumed to deserve it, and likewise, those without power are assumed to be in their proper place. In such a culture, there will be a rigid adherence to the use of titles, “Sir,” “Ma’am,” “Officer,” “Reverend,” and so on. Typically, the directives of those with higher power are to be obeyed with little question. In low power-distance cultures, power distribution is considered far more arbitrary and viewed as a result of luck, money, heritage, or other external variables. Those in power are far more likely to be challenged in a low power-distance culture.

Indicators of power distance within a culture may be income, education, who gets health care and what type, and what types of occupations those with power have versus those who do not have power. According to Hofstede’s most recent data, the five countries with the highest power distances are Malaysia, Slovakia, Guatemala, Panama, and the Philippines (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010). The five countries with the lowest power distances are Austria, Israel, Denmark, New Zealand, and Switzerland (German-speaking part).

Notice that the U.S. does not make it into the top five or the bottom five. According to Hofstede’s data, the U.S. is 16th from the bottom of power distance, so we are in the bottom third with regards to power distance. When it comes down to it, despite the issues we have in our country, the power disparity is not nearly as significant as it is in many other parts of our world. Elected officials, like United States Senators, will be seen as powerful since they had to win their office by receiving majority support. However, individuals who attempt to assert power are often faced with those who stand up to them, question them, ignore them, or otherwise refuse to acknowledge their power. While some titles may be used, they will be used far less than in high power-distance cultures. For example, in colleges and universities in the U.S., it is far more common for students to address their instructors on a first-name basis and engage in casual conversation on personal topics. In contrast, in a high power-distance culture like Japan, the students rise and bow as the teacher enters the room, address them formally at all times, and rarely engage in any personal conversation.

High Uncertainty Avoidance and Low Uncertainty Avoidance

This index shows the degree to which people accept or avoid something strange, unexpected, or different from the status quo. Life is full of uncertainty. We cannot escape it; however, some people are more prone to becoming fearful in situations that are ambiguous or unknown. Uncertainty avoidance then involves the extent to which cultures as a whole are fearful of ambiguous and unknown situations.

Societies with high uncertainty avoidance choose strict rules, guidelines, and behavior codes. They usually depend on absolute truths or the idea that only one truth decides all proper conduct. High uncertainty avoidance cultures limit change and place a very high value on history, doing things as they have been done in the past, and honoring stable cultural norms.

Low uncertainty avoidance cultures see change is seen as inevitable and normal. These cultures are more accepting of contrasting opinions or beliefs. Society is less strict, and a lack of certainty is more acceptable. In a low uncertainty avoidance culture, innovation in all areas is valued. Businesses in the U.S. that can change rapidly, innovate quickly, and respond immediately to market and social pressures are far more successful. Even though the U.S. is generally low in uncertainty avoidance, we can see some evidence of a degree of higher uncertainty avoidance related to certain social issues. As society changes, there are many who will decry the changes as they are “forgetting the past,” “dishonoring our forebears,” or “abandoning sacred traditions.” In the controversy over same-sex marriage, the phrase “traditional marriage” is used to refer to a two person, heterosexual marriage, suggesting same-sex marriage is a violation of tradition. Changing social norms creates uncertainty, and for many, changes are very unsettling.

Long-Term Orientation and Short-Term Orientation

People and cultures view time in different ways. For some, the “here and now” is paramount, and for others, “saving for a rainy day” is the dominant view.

Long-term orientation focuses on the future and not the present or the past. As such, there is a focus on both persistence and thrift. The emphasis on endurance is vital because being persistent today will help you in the future. The goal is to work hard now, so you can have the payoff later. The same is true of thrift. We want to conserve our resources and under-spend to build that financial cushion for the future. Significant emphasis is placed on planning for the future. For example, the savings rates in France and Germany are 2-4 times greater than in the U.S., suggesting cultures with more of a “plan ahead” mentality (Pasquali & Aridas, 2012). These long-term cultures see change and social evolution are normal, integral parts of the human condition.

In a short-term culture, emphasis is placed far more on the “here and now.” Immediate needs and desires are paramount, with longer-term issues left for another day. In these cultures, there tends to be high respect for the past and the various traditions that have made that culture great. Additionally, there is a strong emphasis on “saving face,” which we will discuss later in the book, fulfilling one’s obligations today, and enjoying one’s leisure time. The U.S. falls more into this type. Legislation tends to be passed to handle immediate problems, and it can be challenging for lawmakers to convince voters of the need to look at issues from a long-term perspective. With fairly easy access to credit, consumers are encouraged to buy now versus waiting.

What is Face?

The concept of face is not the easiest to define nor completely understand. Originally, the concept of face is not Western even though the idea of “saving face” is pretty common in everyday talk today. According to Hsien Chin Hu, the concept of face stems from two distinct Chinese words, lien and mien-tzu (Hu, 1994). Lien “represents society’s confidence in the integrity of ego’s moral character, the loss of which makes it impossible for him to function properly within the community. Lien is both a social sanction for enforcing moral standards and an internalized sanction” (Hu, 1994). On the other hand, mien-tzu “stands for the kind of prestige that is emphasized in this country [America]: a reputation achieved through getting on in life, through success and ostentation” (Hu, 1994). However, David Yau-fai Ho argues that face is more complicated than just lien and mien-tzu, so he provided the following definition:

Face is the respectability and/or deference which a person can claim for himself from others, by virtue of the relative position he occupies in his social network and the degree to which he is judged to have functioned adequately in that position as well as acceptably in his general conduct; the face extended to a person by others is a function of the degree of congruence between judgments of his total condition in life, including his actions as well as those of people closely associated with him, and the social expectations that others have placed upon him. In terms of two interacting parties, face is the reciprocated compliance, respect, and/or deference that each party expects from, and extends to, the other party.48

More simplistically, face is essentially “a person’s reputation and feelings of prestige within multiple spheres, including the workplace, the family, personal friends, and society at large” (Upton-McLaughlin, 2013). For our purposes, we can break face down into general categories: face gaining and face losing. Face gaining refers to the strategies a person might use to build their reputation and feelings of prestige (e.g., talking about accomplishments, active social media presence). In contrast, face losing refers to those behaviors someone engages in that can harm their reputation or feelings of prestige (e.g., getting caught in a lie, failing).

Masculine and Feminine

Expectations for gender roles are a core component of any culture. All cultures have a sense of what it means to be a “man” or a “woman.” The notion of masculinity and femininity are often misconstrued to be tied to their biological sex counterparts, female and male. For understanding culture, Hofstede acknowledges that this distinction ultimately has much to do with work goals (Hofstede & Hofstede 2005).

On the masculine end of the spectrum, individuals tend to be focused on items like earnings, recognition, advancement, and challenge. Hofstede also refers to these tendencies as being more assertive. Femininity, on the other hand, involves characteristics like having a good working relationship with one’s manager and coworkers, cooperating with people at work, and security (both job and familial). Hofstede refers to this as being more relationally oriented. Admittedly, in Hofstede’s research, there does tend to be a difference between females and males in these characteristics (females tend to be more relationally oriented and males more assertive), which is why Hofstede went with the terms masculinity and femininity in the first place. Ultimately, we can define these types of cultures in the following way:

A society is called masculine when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life.

A society is called feminine when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life [emphasis in original] (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

In a masculine culture, such as the U.S., winning is highly valued. We respect and honor those who demonstrate power and high degrees of competence. Consider the role of competitive sports such as football, basketball, or baseball and how the rituals of identifying the best are significant events. The 2017 Super Bowl had 111 million viewers, (Huddleston, 2017) and the World Series regularly receives high ratings, with the final game in 2016 ending at the highest rating in ten years (Perez, 2016).

More feminine societies, such as those in the Scandinavian countries, will certainly have their sporting moments. However, the culture is far more structured to provide aid and support to citizens, focusing its energies on providing a reasonable quality of life for all (Hofstede, 2012b).

Indulgence and Restraint

A more recent addition to Hofstede’s dimensions of culture, the indulgence/restraint continuum addresses the degree of rigidity of social norms of behavior. He states:

Indulgence stands for a society that allows relatively free gratification of basic and natural human drives related to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint stands for a society that suppresses gratification of needs and regulates it by means of strict social norms (Hofstede, 2012a).

Indulgent cultures are comfortable with individuals acting on their more basic human drives. Sexual mores are less restrictive, and one can act more spontaneously than in cultures of restraint. Those in indulgent cultures will tend to communicate fewer messages of judgment and evaluation. Every spring, thousands of U.S. college students flock to places like Cancun, Mexico, to engage in a week of fairly indulgent behavior. Feeling free from the social expectations of home, many will engage in some intense partying, sexual activity, and fairly limitless behaviors.

Cultures of restraint, like many Islamic countries, have rigid social expectations of behavior that can be quite narrow. Guidelines on dress, food, drink, and behaviors are rigid and may even be formalized in law. In the U.S., a generally indulgent culture, some sub-cultures are more restraint-focused. The Amish are highly restrained by social norms, but so too can be inner-city gangs. Areas of the country, like Utah with its large Mormon culture, or the Deep South with its large evangelical Christian culture, are more restrained than areas such as San Francisco or New York City. Rural areas often have more rigid social norms than do urban areas. Those in more restraint-oriented cultures will identify those not adhering to these norms, placing pressure on them, either openly or subtly, to conform to social expectations.

Hall’s Cultural Variations

In addition to these six dimensions from Hofstede, anthropologist Edward T. Hall identified two more significant cultural variations (Raimo, 2008).

Monochronic and Polychronic

Another aspect of variations in time orientation is the difference between monochronic and polychronic cultures. This refers to how people perceive and value time.

In a monochronic culture, like the U.S., time is viewed as linear, as a sequential set of finite time units. These units are a commodity, much like money, to be managed and used wisely; once the time is gone, it is gone and cannot be retrieved. Consider the language used to refer to time: spending time; saving time; budgeting time; making time. These are the same terms and concepts we apply to money; time is a resource to be managed thoughtfully. Since we value time so highly, that means:

- Punctuality is valued. Since “time is money,” if a person runs late, they are wasting the resource.

- Scheduling is valued. Since time is finite, only so much is available, we need to plan how to allocate the resource. Monochronic cultures tend to let the schedule drive activity, much like money dictates what we can and cannot afford to do,

- Handling one task at a time is valued. Since time is finite and seen as a resource, monochronic cultures value fulfilling the time budget by doing what was scheduled. Compare this to a financial budget: funds are allocated for different needs, and we assume those funds should be spent on the item budgeted. In a monochronic culture, since time and money are virtually equivalent, adhering to the “time budget” is valued.

- Being busy is valued. Since time is a resource, we tend to view those who are busy as “making the most of their time;” they are seen as using their resources wisely.

In a polychronic culture like Spain, time is far, far more fluid. Schedules are more like rough outlines to be followed, altered, or ignored as events warrant. Relationship development is more important, and schedules do not drive activity. Multi-tasking is far more acceptable, as one can move between various tasks as demands change. In polychronic cultures, people make appointments, but there is more latitude for when they are expected to arrive. David’s appointment may be at 10:15, but as long as he arrives sometime within the 10 o’clock hour, he is on time.

Consider a monochronic person attempting to do business in a polychronic culture. The monochronic person may expect meetings to start promptly on time, stay focused, and for work to be completed in a regimented manner to meet an established deadline. Yet those in a polychronic culture will not bring those same expectations to the encounter, sowing the seeds for some significant intercultural conflict.

High Context and Low Context

The last variation in culture to consider is whether the culture is high context or low context. To establish a little background, consider how we communicate. When we communicate, we use a communication package consisting of all of our verbal and nonverbal communication. As you will learn, our verbal communication refers to our use of language, and our nonverbal communication refers to all other communication variables: body language, vocal traits, and dress.

In low-context cultures, verbal communication is given primary attention. The assumption is that people will say what they mean relatively directly and clearly. Little will be left for the receiver to interpret or imply. In the U.S. if someone does not want something, we expect them to say, “No.” While we certainly use nonverbal communication variables to get a richer sense of the meaning of the person’s message, we consider what they say to be the core, primary message. Those in a high-context culture find the directness of low-context cultures quite disconcerting, to the point of rudeness.

In high-context cultures, nonverbal communication is as important, if not more important, than verbal communication. How something is said is a significant variable in interpreting what is meant. Messages are often implied and delivered quite subtly. Japan is well known for the reluctance of people to use blunt messages, so they have far more subtle ways to indicate disagreement than a low-context culture. Those in low context cultures find these subtle, implied messages frustrating.

In summary, Hofstede’s Dimensions and Hall’s Cultural Variations give us some tools to use to identify, categorize, and discuss diversity in communication. As we learn to see these differences, we are better equipped to manage intercultural encounters, communicate more provisionally, and adapt to cultural variations.

While intended to show only broad cultural differences, these eight variables also can be useful tools to identify variations among individuals within a given culture. We can use them to identify sources of conflict or tension within a given relationship, such as a marriage. For example, Keith tends to be a short-term oriented, indulgent, monochronic person, while his wife tends to be long-term oriented, restrained, and more polychronic. Needless to say, they frequently experience their own personal “culture clashes.”

Exercise

Think about your cultural orientations. Where do you fall on each of the indexes?

Although Hofstede’s and Hall’s Cultural Dimensions are useful in the study of cultures and co-cultures, we must be careful not to oversimplify. The following video illustrates this importance.

Key Takeaways

- Hofstede’s cultural dimensions give us a framework for understanding cultural differences. These differences can help us to understand and thus communicate better with different cultures.

- Hall’s variations add two more important cultural differences to consider when communicating intercultural.

- Within a culture, individuals may have similar or differing preferences for each of the dimensions and variations.

References

This page https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/89683/overview-old is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated.

Hofstede, , & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). Mc- Graw-Hill; pg. 120.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Hu, (1944). The Chinese concepts of “face.” American Anthropologist, 46(1), 45-64. www.jstor.org/sta- ble/662926

Upton-McLaughlin, (2013). Gaining and losing face in China. The China Culture Corner. Retrieved from https://chinaculturecorner.com/2013/10/10/face-in-chinese-business/; para. 2.