Middle Adulthood

This text was last updated as of January 16, 2023 and is no longer being maintained by the author. The current version Psychology Through the Lifespan is available for use.

Why learn about human development during middle adulthood?

This stage of life is truly as multi-faceted as any other. It is a period of negotiation, and renegotiation, across the three main facets of human existence: physical, psychological, and social. Our concept of self may not be fully ours to shape or control alone. How others see us, and their expectations of us, are age-sensitive as well.

From the developmental perspective, middle adulthood (or midlife) refers to the period of the lifespan between young adulthood and old age. This period lasts from 20 to 40 years depending on how these stages, ages, and tasks are culturally defined. The most common definition by chronological age for middle adulthood is from 40 to 65, but there can be a range of up to 10 years (ages 30-75) on either side of these parameters. Research on this period of life is relatively sparse, and many aspects of midlife are still relatively unexplored; in fact, it may be the least studied period of the lifespan. This is not as surprising as might initially appear. One hundred years ago, life expectancy in the United States was about 54 years. How individuals prepare in middle adulthood for living longer and being part of an older community, will assume even more critical importance. It may also present a formidable challenge in the areas of health and public policy, as the relative numbers of those who are economically active, or economically inactive, shift.

Developmental Tasks

Margie Lachman (2004) provides a comprehensive overview of the challenges facing midlife adults, outlining the roles and responsibilities of those entering the “afternoon of life” (Jung). These include:

- Losing parents and experiencing associated grief.

- Launching children into their own lives.

- Adjusting to home life without children (often referred to as the empty nest).

- Dealing with adult children who return to live at home (known as boomerang children in the United States).

- Becoming grandparents.

- Preparing for late adulthood.

- Acting as caregivers for aging parents or spouses.

Taken singly or together, these can represent a fundamental reorientation of outlook, investment, attitudes, and personal relationships which can present formidable obstacles in terms of social and economic challenges. They may also be affected by circumstances outside our control, at a time that we may have envisaged as planned and under control.

What you’ll learn to do: explain the physiological changes during middle adulthood and their physical and psychological consequences

As we will see, there are simple physiological changes that accompany middle adulthood. These are somewhat inevitable, but the importance of physical activity at this age range would be difficult to overstate looking at the evidence. Exercise does not necessarily mean running marathons, it may simply mean a commitment to using your legs in a brisk fashion for thirty minutes. “Use it or lose it” is a good mantra for this stage of development—the technical term for the loss of muscle tissue and function as we age is sarcopenia. From age 30, the body loses 3-8% of its muscle mass per decade, and this accelerates after the age of 60 (Volpi et al., 2010). Diet and exercise can ameliorate the extent and lifestyle consequences of these processes. In this section, we will examine some of the changes associated with middle adulthood and consider how they impact human life.

Learning Outcomes

- Detail the most important physiological changes occurring in men and women during middle adulthood

- Describe how physiological changes during middle adulthood can impact life experience, health, and sexuality

Physical Mobility in Middle Adulthood

The importance of not succumbing to the temptations of a sedentary lifestyle was as obvious to Hippocrates in 400 BCE as it is now. Piasecki et al. (2018) are of the opinion that sarcopenia (loss of muscle tissue and function as we age) in legs might be the result of leg muscles becoming detached from the nervous system. Further, Piasescki et al. (2018) believe that exercise encourages new nerve growth, slowing sarcopenia’s progression. People aged 75 may have up to 30-60% fewer nerve endings in their leg muscles than in their early 20s.

Sarcopenia has only recently been recognized as an independent disease entity since 2016 (ICD-10). In 2018 the U.S. Center for Disease Control and prevention assigned sarcopenia its own discrete medical code. Disease entities that affect mobility will become an increasingly costly phenomenon and affect millions of people’s quality of life as the population ages. In many ways, it is a natural phenomenon, and many doctors and researchers have been reticent to overly pathologize natural changes associated with age. However, mobility is now becoming a central concern, and some researchers are now identifying some conditions like osteosarcopenia, which describes the decline of both muscle tissue (sarcopenia) and bone tissue (osteoporosis). Diagnoses and pharmaceuticals which deal with the central question of mobility will become ever more important, even more so as the burgeoning costs associated with caring for those with mobility issues become apparent.

Human beings reach peak bone mass around 35-40. Osteoporosis is a “silent disease” which progresses until a fracture occurs. The sheer scale and cost of this illness is radically underestimated. It is often associated with women due to the fact that bone mass can deteriorate in women much more quickly in middle age due to menopause. After menopause women can lose 5-10% bone mass per year, rendering it advisable to monitor intakes of calcium and Vitamin D, and evaluate individual risk factors. Beginning in their 60s, though, men and women lose bone mass at roughly the same rate. The number of American men diagnosed with osteoporosis is currently around the 2 million mark, with a further 12 million reckoned to be at risk. The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) estimates that 50% of women and 25% of men over the age of 50 will suffer a bone fracture due to osteoporosis. Attention at this stage of life may bring pronounced health benefits now and later for both women and men. Fixing the damage takes a considerable amount of the Medicare budget.

The health benefits that walking and other physical activity have on the nervous system are becoming increasingly obvious to those who study aging. Adami et al (2018) found pronounced links between weight-bearing exercise and neuron production. We tend to think of the brain as a central processing unit giving instructions to the body via the conduit of the central nervous system, but contemporary science is now coalescing around the idea that muscles and nerves also communicate with the brain—it is a two-way informational and sustaining process. Many studies suggest that voluntary physical activity (VPA) extends and improves the quality of life. Such studies show that even moderate physical activity can bring large gains.

In addition, there is often an increase in chronic inflammation at this time of life with no discernible discrete cause (as opposed to acute inflammation associated with something like an infection). Inflammation is the body’s natural way of responding to bodily injury or harmful pathogens. The function of inflammation is to eliminate the initial cause of injury and initiate tissue repair, but when this happens consistently and for longer periods of time, the body’s stress response systems become overworked. This can have serious effects on health, such as fatigue, fever, chest or abdominal pain, rashes, or greater susceptibility to diseases such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and heart disease. Untreated acute inflammation, autoimmune disorders, or long-term exposure to irritants contribute to social isolation (Nersessian et al, 2018).

Chronic inflammation has been implicated as part of the cause of the muscle loss that occurs with aging. Chronic inflammatory disorder is now implicated in a whole series of chronic diseases such as dementia, and the biomedical evidence for its centrality is now emerging in the medical research literature.

Normal Physiological Changes in Middle Adulthood

There are a few primary biological physical changes in midlife. There are changes in vision, hearing, more joint pain, and weight gain (Lachman, 2004). Weight gain, sometimes referred to as the middle-aged spread or the accumulation of fat in the abdomen, is a common complaint of midlife adults. Men tend to gain fat on their upper abdomen and back while women tend to gain more fat on their waist and upper arms. Many adults are surprised at this weight gain because their diets have not changed. However, the metabolism slows by about one-third during midlife (Berger, 2005). Consequently, midlife adults have to increase their level of exercise, eat less, and watch their nutrition to maintain their earlier physique.

Many of the changes that occur in midlife can be easily compensated for (by buying glasses, exercising, and watching what one eats, for example.) Most midlife adults generally experience good health. However, the percentage of adults who have a disability increases through midlife; while 7 percent of people in their early 40s have a disability, the rate jumps to 30 percent by the early 60s. This increase is highest among those of lower socioeconomic status (Bumpass & Aquilino, 1995).

What can we conclude from this information? Again, lifestyle strongly impacts the health status of midlife adults. Smoking tobacco, drinking alcohol, poor diet, stress, physical inactivity, and chronic diseases such as diabetes or arthritis reduce overall health. It becomes important for midlife adults to take preventative measures to enhance physical well-being. Those midlife adults with a strong sense of mastery and control over their lives, who engage in challenging physical and mental activity, who engage in weight-bearing exercise, monitor their nutrition, and use social resources are most likely to enjoy a plateau of good health through these years. Not only that, but those who begin an exercise regimen in their 40s may enjoy comparable benefits to those who began in their 20s according to Saint-Maurice et al. (2019), who also found that while it is never too late to begin, continuing to do as much as possible, is just as important.

Exercise is a powerful way to combat the changes we associate with aging. Exercise builds muscle, increases metabolism, helps control blood sugar, increases bone density, and relieves stress. Unfortunately, fewer than half of midlife adults exercise and only about 20 percent exercise frequently and strenuously enough to achieve health benefits. Many stop exercising soon after they begin an exercise program-particularly those who are very overweight. The best exercise programs are those that are engaged in regularly—regardless of the activity, but a well-rounded program that is easy to follow includes walking and weight training. Having a safe, enjoyable place to walk can make a difference in whether or not someone walks regularly. Weight lifting and stretching exercises at home can also be part of an effective program. Exercise is particularly helpful in reducing stress in midlife. Walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming can release the tension caused by stressors, and learning relaxation techniques can have healthful benefits. Exercise can be considered preventative health care; promoting exercise for the 78 million “baby boomers” may be one of the best ways to reduce health care costs and improve quality of life (Shure & Cahan, 1998).

Aging brings about a reduction in the number of calories a person requires. Many Americans respond to weight gain by dieting. However, eating less does not necessarily mean eating right; people often suffer vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Very often, physicians will recommend vitamin supplements to their middle-aged patients. As stated above, chronic inflammation is now identified as one of the so-called “pillars of aging”. The link between diet and inflammation is yet unclear. Still, there is now some information available on the Diet Inflammation Index (Shivappa et al., 2014)., which in popular parlance, supports a diet rich in plant-based foods, healthy fats, nuts, fish in moderation, and sparing use of red meat— often referred to as “the Mediterranean Diet.”

The Climacteric

One biologically based change that occurs during midlife is the climacteric. During midlife, men may experience a reduction in their ability to reproduce. Women, however, lose their ability to reproduce once they reach menopause.

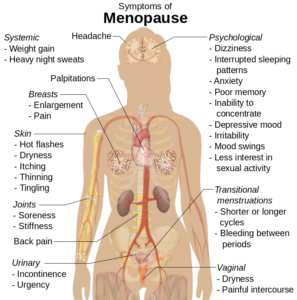

Menopause

Menopause refers to a period of transition in which a woman’s ovaries stop releasing eggs and the level of estrogen and progesterone production decreases. After menopause, a woman’s menstruation ceases (U. S. National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health [NLM/NIH], 2007).

Changes typically occur between the mid-40s and mid-50s. The median age range for a woman to have her last menstrual period is 50-52, but ages vary. A woman may first begin to notice that her periods are more or less frequent than before. These changes in menstruation may last from 1 to 3 years. After a year without menstruation, a woman is considered menopausal and no longer capable of reproduction. (Keep in mind that some women may experience another period even after going for a year without one.) The loss of estrogen also affects vaginal lubrication which diminishes and becomes more watery. The vaginal wall also becomes thinner, and less elastic.

Menopause is not seen as universally distressing (Lachman, 2004). Changes in hormone levels are associated with hot flashes and sweats in some women, but women vary in the extent to which these are experienced. Depression, irritability, and weight gain are not necessarily due to menopause (Avis, 1999; Rossi, 2004). Depression and mood swings are more common during menopause in women with prior histories of these conditions than those who have not. The incidence of depression and mood swings is not greater among menopausal women than non-menopausal women.

Cultural influences seem to also play a role in the way menopause is experienced. For example, once after listing the symptoms of menopause in a psychology course, a woman from Kenya responded, “We do not have this in my country or if we do, it is not a big deal,” to which some U.S. students replied, “I want to go there!” Indeed, there are cultural variations in the experience of menopausal symptoms. Hot flashes are experienced by 75 percent of women in Western cultures, but by less than 20 percent of women in Japan (Obermeyer in Berk, 2007).

Women in the United States respond differently to menopause depending on their expectations for themselves and their lives. White, career-oriented women, African-American, and Mexican-American women overall tend to think of menopause as a liberating experience. Nevertheless, there has been a popular tendency to erroneously attribute frustrations and irritations expressed by women of menopausal age to menopause and thereby not take her concerns seriously. Fortunately, many practitioners in the United States today are normalizing rather than pathologizing menopause.

Concerns about the effects of hormone replacement have changed the frequency with which estrogen replacement and hormone replacement therapies have been prescribed for menopausal women. Estrogen replacement therapy was once commonly used to treat menopausal symptoms. But more recently, hormone replacement therapy has been associated with breast cancer, stroke, and the development of blood clots (NLM/NIH, 2007). Most women do not have symptoms severe enough to warrant estrogen or hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Women who do require HRT can be treated with lower doses of estrogen and monitored with more frequent breast and pelvic exams. There are also some other ways to reduce symptoms. These include avoiding caffeine and alcohol, eating soy, remaining sexually active, practicing relaxation techniques, and using water-based lubricants during intercourse.

Fifty million women in the USA aged 50-55 are post-menopausal. During and after menopause a majority of women will experience weight gain. Changes in estrogen levels lead to a redistribution of body fat from hips and back to stomachs. This is more dangerous to general health and wellbeing because abdominal fat is largely visceral, meaning it is contained within the abdominal cavity and may not look like typical weight gain. That is, it accumulates in the space between the liver, intestines, and other vital organs. This is far more harmful to health than subcutaneous fat, the kind of fat located under the skin. It is possible to be relatively thin and retain a high level of visceral fat, yet this type of fat is deemed especially harmful by medical research.

Andropause

Do males experience a climacteric? Yes. While they do not lose their ability to reproduce as they age, they tend to produce lower testosterone levels and fewer sperm. However, men are capable of reproduction throughout life after puberty. It is natural for sex drive to diminish slightly as men age, but a lack of sex drive may be a result of extremely low levels of testosterone. About 5 million men experience low levels of testosterone that results in symptoms such as a loss of interest in sex, loss of body hair, difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection, loss of muscle mass, and breast enlargement. This decrease in libido and lower testosterone (androgen) levels is known as andropause, although this term is somewhat controversial as this experience is not clearly delineated, as menopause is for women. Low testosterone levels may be due to glandular diseases such as testicular cancer. Testosterone levels can be tested; if they are low, men can be treated with testosterone replacement therapy. This can increase sex drive, muscle mass, and beard growth. However, long term HRT for men can increase the risk of prostate cancer (The Patient Education Institute, 2005).

The debate around declining testosterone levels in men may hide a fundamental fact. The issue is not about individual males experiencing individual hormonal change at all. We have all seen the adverts on the media promoting substances to boost testosterone: “Is it low-T?” The answer is probably in the affirmative, if somewhat relative. That is, in all likelihood, they will have lower testosterone levels than their fathers. However, it is equally likely that the issue does not lie solely in their individual physiological makeup, but is rather a generational transformation (Travison et al, 2007). Why this has occurred in such a dramatic fashion is still unknown. There is evidence that low testosterone may have negative health effects on men. In addition, some studies show evidence of rapidly decreasing sperm count and grip strength. Exactly why these changes are happening is unknown and will likely involve more than one cause.

The Climacteric and Sexuality

Sexuality is an important part of people’s lives at any age. Midlife adults tend to have sex lives that are very similar to that of younger adults. And many women feel freer and less inhibited sexually as they age. However, a woman may notice less vaginal lubrication during arousal and men may experience changes in their erections from time to time. This is particularly true for men after age 65. Men who experience consistent problems are likely to have other medical conditions (such as diabetes or heart disease) that impact sexual functioning (National Institute on Aging, 2005).

Couples continue to enjoy physical intimacy and may engage in more foreplay, oral sex, and other forms of sexual expression rather than focusing as much on sexual intercourse. The risk of pregnancy continues until a woman has been without menstruation for at least 12 months. However, couples should continue to use contraception. People continue to be at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections such as genital herpes, chlamydia, and genital warts. Seventeen percent of new cases of AIDS in the United States are in people 50 and older. Of all people living with HIV, 47% are aged 50 or over. Practicing safe sex is important at any age- safe sex is not just about avoiding an unwanted pregnancy but also about protecting yourself from STDs. Hopefully, when partners understand how aging affects sexual expression, they will be less likely to misinterpret these changes as a lack of sexual interest or displeasure in the partner and be more able to continue to have satisfying and safe sexual relationships.

What you’ll learn to do: describe cognitive and neurological changes during middle adulthood

While we sometimes associate aging with cognitive decline (often due to how it is portrayed in the media), aging does not necessarily mean a decrease in cognitive function. In fact, tacit knowledge, verbal memory, vocabulary, inductive reasoning, and other types of practical thought skills increase with age. We’ll learn about these advances as well as some neurological changes that happen in middle adulthood in the section that follows.

Learning Outcomes

- Outline cognitive gains/deficits typically associated with middle adulthood

- Explain changes in fluid and crystallized intelligence during adulthood

Cognition in Middle Adulthood

One of the most influential perspectives on cognition during middle adulthood was the Seattle Longitudinal Study (SLS) of adult cognition, which began in 1956. Schaie & Willis (2010) summarized the general findings from this series of studies as follows: “We have generally shown that reliably replicable average age decrements in psychometric abilities do not occur before age 60, but that such reliable decrement can be found for all abilities by 74 years of age.” In short, decreases in cognitive abilities begin in the sixth decade and gain increasing significance from that point on. However, Singh-Maoux et al. (2012) argue for small but significant cognitive declines beginning as early as age 45. There is some evidence that adults should be as aggressive in maintaining their cognitive health as they are in their physical health during this time as the two are intimately related.

The second source of longitudinal research data on this part of the lifespan has been The Midlife in the United States Studies (MIDUS), which began in 1994. The MIDUS data supports the view that this period of life is something of a trade-off, with some cognitive and physical decreases of varying degrees. The cognitive mechanics of processing speed often referred to as fluid intelligence, physiological lung capacity, and muscle mass, are in relative decline. However, knowledge, experience, and the increased ability to regulate our emotions can compensate for these losses. Continuing cognitive focus and exercise can also reduce the extent and effects of cognitive decline.

Control Beliefs

Central to all of this are personal control beliefs, which have a long history in psychology. Beginning with the work of Julian Rotter (1954), a fundamental distinction is drawn between those who believe that they are the fundamental agent of what happens in their lives and those who believe that they are largely at the mercy of external circumstances. Those who believe that life outcomes are dependent on what they say and do are said to have a strong internal locus of control. Those who believe that they have little control over their life outcomes are said to have an external locus of control.

Empirical research has shown that those with an internal locus of control enjoy better results in psychological tests across the board; behavioral, motivational, and cognitive. It is reported that this belief in control declines with age, but again, there is a great deal of individual variation. This raises another issue: directional causality. Does my belief in my ability to retain my intellectual skills and abilities at this time of life ensure better performance on a cognitive test compared to those who believe in their inexorable decline? Or, does the fact that I enjoy that intellectual competence or facility instill or reinforce that belief in control and controllable outcomes? It is not clear which factor is influencing the other. The exact nature of the connection between control beliefs and cognitive performance remains unclear.

Brain science is developing exponentially and will unquestionably deliver new insights on a whole range of issues related to cognition in midlife. One of them will surely be on the brain’s capacity to renew, or at least replenish itself, at this time of life. The capacity to renew is called neurogenesis; the capacity to replenish what is there is called neuroplasticity. At this stage, it is impossible to ascertain exactly what effect future pharmacological interventions may have on the possible cognitive decline at this, and later, stages of life.

Cognitive Aging

Researchers have identified areas of loss and gain in cognition in older age. Cognitive ability and intelligence are often measured using standardized tests and validated measures. The psychometric approach has identified two categories of intelligence that show different rates of change across the life span (Schaie & Willis, 1996). Fluid and crystallized intelligence were first identified by Cattell in 1971. Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge. Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts. There is a general acceptance that fluid intelligence decreases continually from the 20s, but that crystallized intelligence continues to accumulate. One might expect to complete the NY Times crossword more quickly at 48 than 22, but the capacity to deal with novel information declines.

With age, systematic declines are observed on cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing, without the aid of supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). Older adults tend to perform poorer than young adults on memory tasks that involve recall of information, where individuals must retrieve the information they learned previously without the help of a list of possible choices. For example, older adults may have more difficulty recalling facts such as names or contextual details about where or when something happened (Craik, 2000). What might explain these deficits as we age?

As we age, working memory, or our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences in many different cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition memory tasks, or when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well if not better than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at the printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts are able to focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults to make better decisions than young adults (Tentori, Osheron, Hasher, & May, 2001).

We began with Schaie and Willis (2010) observing that no discernible general cognitive decline could be observed before 60, but other studies contradict this notion. How do we explain this contradiction? In a thought-provoking article, Ramscar et al. (2014) argued that an emphasis on information processing speed ignored the effect of the process of learning/experience itself; that is, that such tests ignore the fact that more information to process leads to slower processing in both computers and humans. We are more complex cognitive systems at 55 than 25.

Performance in Middle Adulthood

Research on interpersonal problem solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform less well on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive decline.

Empirical studies of cognitive aging are often difficult, and quite technical, given their nature. Similarly, experiments focused on one task may tell you very little about general capacities. Memory and attention as psychological constructs are now divided into very specific subsets which can be confusing and difficult to compare.

However, one study does show with relative clarity the issues involved. In the USA, The Federal Aviation Authority insists that all air traffic controllers retire at 56 and that they cannot begin until age 31 unless they have previous military experience. However, in Canada controllers are allowed to work until aged 65 and are allowed to train at a much earlier age. Nunes and Kramer (2009) studied four groups: a younger group of controllers (20-27), an older group of controllers aged 53 to 64, and two other groups of the same age who were not air traffic controllers. On simple cognitive tasks, not related to their occupational lives as controllers, older controllers were slower than their younger peers. However, when it came to job-related tasks their results were largely identical. This was not true of the older group of non-controllers who had significant deficits in comparison. Specific knowledge or expertise in a domain acquired over time (crystallized intelligence), can offset a decline in fluid intelligence.

Tacit Knowlege

The idea of tacit knowledge was first introduced by Michael Polanyi (1954). He argued that each individual had a huge store of knowledge based on life experience but that it was often difficult to describe, codify, and thus transfer, as stated in his famous formulation, “we always know more than we can tell.” Organizational theorists have spent a great deal of time thinking about the problem of tacit knowledge in this setting. Think of someone you have encountered who is extremely good at their work. They may have no more (or less) education, formal training, and even experience, than others who are supposedly at an equivalent level. What is the “something” that they have? Tacit knowledge is highly prized and older workers often have the greatest amount, even if they are not conscious of that fact.

What you’ll learn to do: analyze emotional and social development in middle adulthood

Traditionally, middle adulthood has been regarded as a period of reflection and change. In the popular imagination (and academic press) there has been a reference to a “mid-life crisis.” There is an emerging view that this may have been an overstatement—certainly, the evidence on which it is based has been seriously questioned. However, there is some support for the view that people undertake an emotional audit, reevaluate their priorities, and emerge with a slightly different orientation to emotional regulation and personal interaction in this period. Why and the mechanisms through which this change is affected are a matter of debate. We will examine the ideas of Erikson, Baltes, and Carstensen, and how they might inform a more nuanced understanding of this vital part of the lifespan.

Learning outcomes

- Describe Erikson’s stage of generativity vs. stagnation

- Evaluate Levinson’s notion of the midlife crisis

- Examine key theories on aging, including socio-emotional selectivity theory (SSC) and selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC)

- Describe personality and work-related issues in midlife

Psychosocial Development in Midlife

What do you think is the happiest stage of life? What about the saddest stages? Perhaps surprisingly, Blanchflower & Oswald (2008) found that reported levels of unhappiness and depressive symptoms peak in the early 50s for men in the U.S., and interestingly, the late 30s for women. In Western Europe, minimum happiness is reported around the mid-40s for both men and women, albeit with some significant national differences. Stone et al. (2017), reported a precipitous drop in perceived stress in men in the U.S. from their early 50s. There is now a view that “older people” (50+) may be “happier” than younger people, despite some cognitive and functional losses. This is often referred to as “the paradox of aging.” Positive attitudes to the continuance of cognitive and behavioral activities, interpersonal engagement, and their vitalizing effect on human neural plasticity may lead to more life and to an extended period of self-satisfaction and continued communal engagement.

Erikson’s Theory

| Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Generativity vs. Stagnation (Care)—When people reach their 40s, they enter the time known as middle adulthood, which extends to the mid-60s. The social task of middle adulthood is generativity vs. stagnation the fundamental conflict of adulthood. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. During this stage, middle-aged adults begin contributing to the next generation, often through caring for others; they also engage in meaningful and productive work that contributes positively to society.

As you know by now, Erikson’s theory is based on an idea called epigenesis, meaning that development is progressive and that each individual must pass through the eight different stages of life—all while being influenced by context and environment. Each stage forms the basis for the following stage, and each transition to the next is marked by a crisis that must be resolved. The sense of self, each “season”, was wrested, from and by, that conflict. The ages of 40-65 are no different. The individual is still driven to engage productively, but the nurturing of children and income generation assume lesser functional importance. From where will the individual derive their sense of self and self-worth?

Generativity is “primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation” (Erikson, 1950, p.267). Generativity is a concern for a generalized other (as well as those close to an individual) and occurs when a person can shift their energy to care for and mentor the next generation. One obvious motive for this generative thinking might be parenthood, but others have suggested intimations of mortality by the self. Kotre (1984) theorized that generativity is a selfish act, stating that its fundamental task was to outlive the self. He viewed generativity as a form of investment. However, a commitment to a “belief in the species” can be taken in numerous directions, and it is probably correct to say that most modern treatments of generativity treat it as a collection of facets or aspects—encompassing creativity, productivity, commitment, interpersonal care, and so on.

On the other side of generativity is stagnation. It is the lethargy, lack of enthusiasm, and involvement in individual and communal affairs. It may also denote an underdeveloped sense of self or some form of overblown narcissism. Erikson sometimes used the word “rejectivity” when referring to severe stagnation. Those who do not master this task may experience stagnation and feel as though they are not leaving a mark on the world in a meaningful way; they may have little connection with others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.

The Stage-Crisis View and the Midlife Crisis

In 1977, Daniel Levinson published an extremely influential article that would be seminal in establishing the idea of a profound crisis that lies at the heart of middle adulthood. The concept of a midlife crisis is so pervasive that over 90% of Americans are familiar with the term, although those who actually report experiencing such a crisis is significantly lower (Wethington, 2000).

Levinson based his findings of a midlife crisis on biographical interviews with a limited sample of 40 men (no women!), and an entirely American sample at that. Despite these severe methodological limitations, his findings proved immensely influential. Levinson (1986) identified five main stages or “seasons” of a man’s life as follows:

- Preadulthood: Ages 0-22 (with 17 – 22 being the Early Adult Transition years)

- Early Adulthood: Ages 17-45 (with 40 – 45 being the Midlife Transition years)

- Middle Adulthood: Ages 40-65 (with 60-65 being the Late Adult Transition years)

- Late Adulthood: Ages 60-85

- Late Late Adulthood: Ages 85+

Levinson’s theory is known as the stage-crisis view. He argued that each stage overlaps, consisting of two distinct phases—a stable phase, and a transitional phase into the following period. The latter phase can involve questioning and change, and Levinson believed that 40-45 was a period of profound change, which could only culminate in a reappraisal, or perhaps reaffirmation, of goals, commitments and previous choices—a time for taking stock and recalibrating what was important in life. Crucially, Levinson would argue that a much wider range of factors, primarily work and family, would affect this taking stock – what he had achieved, what he had not; what he thought important, but had brought only limited satisfaction.

In 1996, two years after his death, the study he was conducting with his co-author and wife Judy Levinson, was published on “the seasons of life” as experienced by women. Again, it was a small scale study, with 45 women who were professionals/businesswomen, academics, and homemakers, in equal proportion. The changing place of women in society was reckoned by Levinson to be a profound moment in the social evolution of the human species. However, it had led to a fundamental polarity in the way that women formed and understood their social identity. Levinson referred to this as the “dream.” For men, the “dream” was formed in the age period of 22-28, and largely centered on the occupational role and professional ambitions. Levinson understood the female “dream” as fundamentally split between this work-centered orientation, and the desire/imperative of marriage/family; a polarity that heralded both new opportunities, and fundamental angst.

Levinson found that the men and women he interviewed sometimes had difficulty reconciling the “dream” they held about the future with the reality they currently experienced. “What do I really get from and give to my wife, children, friends, work, community, and self?” a man might ask (Levinson, 1978, p. 192). Tasks of the midlife transition include:

- ending early adulthood;

- reassessing life in the present and making modifications if needed; and

- reconciling “polarities” or contradictions in one’s sense of self.

Perhaps early adulthood ends when a person no longer seeks adult status but feels like a full adult in the eyes of others. This “permission” may lead to different choices in life—choices that are made for self-fulfillment instead of social acceptance. While people in their 20s may emphasize how old they are (to gain respect, to be viewed as experienced), by the time people reach their 40s, they tend to emphasize how young they are (few 40-year-olds cut each other down for being so young: “You’re only 43? I’m 48!!”).

This new perspective on time brings about a new sense of urgency to life. The person becomes focused more on the present than the future or the past. The person grows impatient at being in the “waiting room of life,” postponing doing the things they have always wanted to do. “If it’s ever going to happen, it better happen now.” A previous focus on the future gives way to an emphasis on the present. Neugarten (1968) notes that in midlife, people no longer think of their lives in terms of how long they have lived. Rather, life is thought of in terms of how many years are left. If an adult is not satisfied at midlife, there is a new sense of urgency to make changes.

Changes may involve ending a relationship or modifying one’s expectations of a partner. These modifications are easier than changing the self (Levinson, 1978). Midlife is a period of transition in which one holds earlier images of the self while forming new ideas about the self of the future. A greater awareness of aging accompanies feelings of youth, and harm that may have been done previously in relationships haunts new dreams of contributing to the well-being of others. These polarities are the quieter struggles that continue after outward signs of “crisis” have gone away.

Levinson characterized midlife as a time of developmental crisis. However, like any body of work, it has been subject to criticism. Firstly, the sample size of the populations on which he based his primary findings is too small. By what right do we generalize findings from interviews with 40 men and 45 women, however thoughtful and well-conducted? Secondly, Chiriboga (1989) could not find any substantial evidence of a midlife crisis, and it might be argued that this and further failed replication attempts indicate a cohort effect. The findings from Levinson’s population indicated a shared historical and cultural situatedness rather than a cross-cultural universal experienced by all or even most individuals. Midlife is a time of revaluation and change, that may escape precise determination in both time and geographical space, but people do emerge from it, and seem to enjoy a period of contentment, reconciliation, and acceptance of self.

Socio-Emotional Selectivity Theory (SST)

It is the inescapable fate of human beings to know that their lives are limited. As people move through life, goals, and values tend to shift. What we consider priorities, goals, and aspirations are subject to renegotiation. Attachments to others, current, and future, are no different. Time is not the unlimited good as perceived by a child under normal social circumstances; it is very much a valuable commodity, requiring careful consideration in terms of the investment of resources. This has become known in academic literature as mortality salience.

Mortality salience posits that reminders about death or finitude (at either a conscious or subconscious level), fills us with dread. We seek to deny its reality, but awareness of the increasing nearness of death can have a potent effect on human judgment and behavior. This has become a very important concept in contemporary social science. It is with this understanding that Laura Carstensen developed the theory of socioemotional selectivity theory or SST. The theory maintains that as time horizons shrink, as they typically do with age, people become increasingly selective, investing greater resources in emotionally meaningful goals and activities. According to the theory, motivational shifts also influence cognitive processing. Aging is associated with a relative preference for positive over negative information. This selective narrowing of social interaction maximizes positive emotional experiences and minimizes emotional risks as individuals become older. They systematically hone their social networks so that available social partners satisfy their emotional needs. The French philosopher Sartre observed that “hell is other people”. An adaptive way of maintaining a positive effect might be to reduce contact with those we know may negatively affect us, and avoid those who might.

SST is a theory that emphasizes a time perspective rather than chronological age. When people perceive their future as open-ended, they tend to focus on future-oriented development or knowledge-related goals. When they feel that time is running out, and the opportunity to reap rewards from future-oriented goals’ realization is dwindling, their focus tends to shift towards present-oriented and emotion or pleasure-related goals. Research on this theory often compares age groups (e.g., young adulthood vs. old adulthood), but the shift in goal priorities is a gradual process that begins in early adulthood. Importantly, the theory contends that the cause of these goal shifts is not age itself, i.e., not the passage of time itself, but rather an age-associated shift in time perspective. The theory also focuses on the types of goals that individuals are motivated to achieve. Knowledge-related goals aim at knowledge acquisition, career planning, the development of new social relationships, and other endeavors that will pay off in the future. Emotion-related goals are aimed at emotion regulation, the pursuit of emotionally gratifying interactions with social partners, and other pursuits whose benefits can be realized in the present.

This shift in emphasis, from long term goals to short term emotional satisfaction, may help explain the previously noted “paradox of aging.” That is, that despite noticeable physiological declines, and some notable self-reports of reduced life-satisfaction around this time, post- 50 there seems to be a significant increase in reported subjective well-being. SST does not champion social isolation, which is harmful to human health, but shows that increased selectivity in human relationships, rather than abstinence, leads to more positive affect. Perhaps “midlife crisis and recovery” may be a more apt description of the 40-65 period of the lifespan.

Personality and Work Satisfaction

Personality in Midlife

Research on adult personality examines normative age-related increases and decreases in the expression of the so-called “Big Five” traits. The Big Five domains include extraversion (attributes such as assertive, confident, independent, outgoing, and sociable), agreeableness (attributes such as cooperative, kind, modest, and trusting), conscientiousness (attributes such as hard-working, dutiful, self-controlled, and goal-oriented), neuroticism (attributes such as anxious, tense, moody, and easily angered), and openness (attributes such as artistic, curious, inventive, and open-minded). The Big Five is one of the most common ways of organizing the vast range of personality attributes that seem to distinguish one person from the next. This organizing framework made it possible for Roberts et al. (2006) to draw broad conclusions from the literature.

These are assumed to be based largely on biological heredity. These five traits are sometimes summarized via the OCEAN acronym. Individuals are assessed by measuring these traits along a continuum (e.g. high extroversion to low extroversion). They now dominate the field of empirical personality research. Does personality change throughout adulthood? Previously the answer was thought to be no. It was William James who stated in his foundational text, The Principles of Psychology (1890), that “[i]n most of us, by the age of thirty, the character is set like plaster, and will never soften again”. Not surprisingly, this became known as the plaster hypothesis.

Contemporary research shows that, although some people’s personalities are relatively stable over time, others’ are not (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood, and individual differences in these patterns over the lifespan may be due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce, illness). In general, average levels of extraversion (especially the attributes linked to self-confidence and independence), agreeableness, and conscientiousness appear to increase with age whereas neuroticism appears to decrease with age (Roberts et al., 2006). Openness also declines with age, especially after mid-life (Roberts et al., 2006). These changes are often viewed as positive trends given that higher levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness and lower levels of neuroticism are associated with seemingly desirable outcomes such as increased relationship stability and quality, greater success at work, better health, a reduced risk of criminality and mental health problems, and even decreased mortality (e.g., Kotov et al., 2010; Miller & Lynam 2001; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts et al., 2007). This pattern of positive average changes in personality attributes is known as the maturity principle of adult personality development (Caspi et al., 2005). The basic idea is that attributes associated with positive adaptation and attributes associated with the successful fulfillment of adult roles tend to increase during adulthood in terms of their average levels.

Carl Jung believed that our personality actually matures as we get older. A healthy personality is balanced. People suffer tension and anxiety when they fail to express all of their inherent qualities. Jung believed that each of us possesses a “shadow side.” For example, those typically introverted also have an extroverted side that rarely finds expression unless we are relaxed and uninhibited. Each of us has both a masculine and feminine side, but in younger years, we feel societal pressure to give expression only to one. As we get older, we may become freer to express all of our traits as the situation arises. We find gender convergence in older adults. Men become more interested in intimacy and family ties. Women may become more assertive. This gender convergence is also affected by changes in society’s expectations for males and females. With each new generation, we find that the roles of men and women are less stereotypical, which also allows for change.

Subjective Aging

One aspect of the self that particularly interests life span and life course psychologists is the individual’s perception and evaluation of their own aging and identification with an age group. Subjective age is a multidimensional construct that indicates how old (or young) a person feels, and into which age group a person categorizes themself. After early adulthood, most people say they feel younger than their chronological age, and the gap between subjective and actual age generally increases. On average, after age 40 people report feeling 20% younger than their actual age (e.g., Rubin & Berntsen, 2006). Asking people how satisfied they are with their own aging assesses an evaluative component of age identity. Whereas some aspects of age identity are positively valued (e.g., acquiring seniority in a profession or becoming a grandparent), others may be less valued, depending on societal context. Perceived physical age (i.e., the age one looks in a mirror) is one aspect that requires considerable self-related adaptation in social and cultural contexts that value young bodies. Feeling younger and being satisfied with one’s own aging are expressions of positive self-perceptions of aging. They reflect the operation of self-related processes that enhance well-being. Levy (2009) found that older individuals who can adapt to and accept changes in their appearance and physical capacity in a positive way report higher well-being, have better health, and live longer.

There is now an increasing acceptance of the view within developmental psychology that an uncritical reliance on chronological age may be inappropriate. People have certain expectations about getting older, their own idiosyncratic views, and internalized societal beliefs. Taken together they constitute a tacit knowledge of the aging process. A negative perception of how we are aging can have real results in terms of life expectancy and poor health. Levy et al. (2002) estimated that those with positive feelings about aging lived 7.5 years longer than those who did not. Subjective aging encompasses a wide range of psychological perspectives and empirical research. However, there is now a growing body of work centered around a construct referred to as Awareness of Age-Related Change (AARC) (Diehl et al., 2015), which examines the effects of our subjective perceptions of age and their consequential, and very real, effects. Neuport & Bellingtier (2017) report that this subjective awareness can change on a daily basis, and that negative events or comments can disproportionately affect those with the most positive outlook on aging.

Work Satisfaction

Middle adulthood is characterized by a time of transition, change, and renewal. Accordingly, attitudes about work and satisfaction from work tend to undergo a transformation or reorientation during this time. Age is positively related to job satisfaction—the older we get the more we derive satisfaction from work (Ng & Feldman, 2010). However, that is far from the entire story and repeats, once more, the paradoxical nature of the research findings from this period of the life course. Dobrow, Gazach & Liu (2018) found that job satisfaction in those aged 43-51 was correlated with advancing age, but that there was increased dissatisfaction the longer one stayed in the same job. Again, as socio-emotional selectivity theory would predict, there is a marked reluctance to tolerate a work situation deemed unsuitable or unsatisfying. Years left, as opposed to years spent, necessitates a sense of purpose in all daily activities and interactions, including work.

Some people love their jobs, some people tolerate their jobs, and some people cannot stand their jobs. Job satisfaction describes the degree to which individuals enjoy their job. It was described by Edwin Locke (1976) as the state of feeling resulting from appraising one’s job experiences. While job satisfaction results from both how we think about our work (our cognition) and how we feel about our work (our affect) (Saari & Judge, 2004), it is described in terms of effect. Job satisfaction is impacted by the work itself, our personality, and the culture we come from and live in (Saari & Judge, 2004).

Job satisfaction is typically measured after a change in an organization, such as a shift in the management model, to assess how the change affects employees. It may also be routinely measured by an organization to assess one of many factors expected to affect the organization’s performance. In addition, polling companies like Gallup regularly measure job satisfaction nationally to gather broad information on the state of the economy and the workforce (Saad, 2012).

Job satisfaction is measured using questionnaires that employees complete. Sometimes a single question might be asked in a very straightforward way to which employees respond using a rating scale, such as a Likert scale, which was discussed in the chapter on personality. A Likert scale (typically) provides five possible answers to a statement or question that allows respondents to indicate their positive-to-negative strength of agreement or strength of feeling regarding the question or statement. Thus the possible responses to a question such as “How satisfied are you with your job today?” might be “Very satisfied,” “Somewhat satisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Somewhat dissatisfied,” and “Very dissatisfied.” More commonly the survey will ask a number of questions about the employee’s satisfaction to determine more precisely why he is satisfied or dissatisfied. Sometimes these surveys are created for specific jobs; at other times, they are designed to apply to any job. Job satisfaction can be measured at a global level, meaning how satisfied in general the employee is with work, or at the level of specific factors intended to measure which aspects of the job lead to satisfaction (Table 13.2).

| Factors Involved in Job Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction | |

|---|---|

| Factor | Description |

| Autonomy | Individual responsibility, control over decisions |

| Work content | Variety, challenge, role clarity |

| Communication | Feedback |

| Financial rewards | Salary and benefits |

| Growth and development | Personal growth, training, education |

| Promotion | Career advancement opportunity |

| Coworkers | Professional relations or adequacy |

| Supervision and feedback | Support, recognition, fairness |

| Workload | Time pressure, tedium |

| Work demands | Extra work requirements, insecurity of position |

Research has suggested that the work-content factor, which includes variety, difficulty level, and role clarity of the job, is the most strongly predictive factor of overall job satisfaction (Saari & Judge, 2004). In contrast, there is only a weak correlation between pay level and job satisfaction (Judge et al., 2010). It is suggested that individuals adjust or adapt to higher pay levels: Higher pay no longer provides the satisfaction the individual may have initially felt when her salary increased.

Why should we care about job satisfaction? Or more specifically, why should an employer care about job satisfaction? Measures of job satisfaction are somewhat correlated with job performance; in particular, they appear to relate to organizational citizenship or discretionary behaviors on the part of an employee that further the goals of the organization (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Job satisfaction is related to general life satisfaction, although there has been limited research on how the two influence each other or whether personality and cultural factors affect both job and general life satisfaction. One carefully controlled study suggested that the relationship is reciprocal: Job satisfaction affects life satisfaction positively, and vice versa (Judge & Watanabe, 1993). Of course, organizations cannot control life satisfaction’s influence on job satisfaction. Job satisfaction, specifically low job satisfaction, is also related to withdrawal behaviors, such as leaving a job or absenteeism (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). The relationship with turnover itself, however, is weak (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Finally, it appears that job satisfaction is related to organizational performance, which suggests that implementing organizational changes to improve employee job satisfaction will improve organizational performance (Judge & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012).

There is an opportunity for more research in the area of job satisfaction. For example, Weiss (2002) suggests that the concept of job satisfaction measurements have combined both emotional and cognitive concepts, and measurements would be more reliable and show better relationships with outcomes like performance if the measurement of job satisfaction separated these two possible elements of job satisfaction.

The workplace today is one in which many people from various walks of life come together. Work schedules are more flexible and varied, and more work independently from home or anywhere there is an internet connection. The midlife worker must be flexible, stay current with technology, and be capable of working within a global community.

Work-Family Balance

Many people juggle the demands of work-life with the demands of their home life, whether it be caring for children or taking care of an elderly parent; this is known as work-family balance. We might commonly think about work interfering with family, but it is also the case that family responsibilities may conflict with work obligations (Carlson, Kacmar, & Williams, 2000). Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) first identified three sources of work-family conflicts:

- time devoted to work makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of family or vice versa,

- strain from participation in work makes it difficult to fulfill requirements of family or vice versa, and

- specific behaviors required by work make it difficult to fulfill the requirements of family or vice versa.

Women often have greater responsibility for family demands, including home care, child care, and caring for aging parents, yet men in the United States are increasingly assuming a greater share of domestic responsibilities. However, research has documented that women report greater levels of stress from work-family conflict (Gyllensten & Palmer, 2005).

There are many ways to decrease work-family conflict and improve people’s job satisfaction (Posig & Kickul, 2004). These include support in the home, which can take various forms: emotional (listening), practical (help with chores). Workplace support can include understanding supervisors, flextime, leave with pay, and telecommuting. Flextime usually requires core hours spent in the workplace around which the employee may schedule his arrival and departure to meet family demands. Telecommuting involves employees working at home and setting their own hours, which allows them to work during different parts of the day, and to spend part of the day with their family; this may also be known as e-commuting, working remotely, flexible workspace, or simply working from home. Recall that Yahoo! had a policy of allowing employees to telecommute and then rescinded the policy. Some organizations have onsite daycare centers, and some companies even have onsite fitness centers and health clinics. In a study of the effectiveness of different coping methods, Lapierre & Allen (2006) found practical support from home more important than emotional support. They also found that immediate-supervisor support for a worker significantly reduced work-family conflict through such mechanisms as allowing an employee the flexibility needed to fulfill family obligations. In contrast, flextime did not help with coping and telecommuting actually made things worse, perhaps reflecting the fact that being at home intensifies the conflict between work and family because, with the employee in the home, the demands of family are more evident.

Posig & Kickul (2004) identify exemplar corporations with policies that reduce work-family conflict. Examples include IBM’s policy of three years of job-guaranteed leave after the birth of a child, Lucent Technologies offer of one year’s childbirth leave at half-pay and SC Johnson’s program of concierge services for daytime errands.

Relationships at Work

Working adults spend a large part of their waking hours in relationships with coworkers and supervisors. Because these relationships are forced upon us by work, researchers focus less on their presence or absence and instead focus on their quality. High quality work relationships can make jobs enjoyable and less stressful. This is because workers experience mutual trust and support in the workplace to overcome work challenges. Liking the people we work with can also translate to more humor and fun on the job. Research has shown that more supportive supervisors have employees who are more likely to thrive at work (Paterson, Luthans, & Jeung, 2014; Monnot & Beehr, 2014; Winkler, Busch, Clasen, & Vowinkel, 2015). On the other hand, poor quality work relationships can make a job feel like a drudgery. Everyone knows that horrible bosses can make the workday unpleasant. Supervisors that are sources of stress negatively impact their employees’ subjective well-being (Monnot & Beehr, 2014). Specifically, research has shown that employees who rate their supervisors high on the so-called “dark triad”—psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism—reported greater psychological distress at work and less job satisfaction (Mathieu et al., 2014).

In addition to the direct benefits or costs of work relationships on our well-being, we should also consider how these relationships can impact our job performance. Research has shown that feeling engaged in our work and having a high job performance predicts better health and greater life satisfaction (Shimazu et al., 2015). Given that so many of our waking hours are spent on the job—about 90,000 hours across a lifetime—it makes sense that we should seek out and invest in positive relationships at work.

One of the most influential researchers in this field, Dorien Kooij (2013) identified four key motivations in older adults continuing to work. First, growth or development motivation- looking for new challenges in the work environment. The second are feelings of recognition and power. Third, feelings of power and security afforded by income and possible health benefits. Interestingly enough, the fourth area of motivation was Erikson’s generativity. The latter has been criticized for a lack of support in terms of empirical research findings, but two studies (Zacher et al., 2012; Ghislieri & Gatti, 2012) found that a primary motivation in continuing to work was the desire to pass on skills and experience, a process they describe as leader generativity. Perhaps a more straightforward term might be mentoring. In any case, the generative leadership concept is firmly established in the business and organizational management literature.

Organizations, public and private, are going to have to deal with an older workforce. The proportion of people in Europe over 60 will increase from 24% to 34% by 2050 (United Nations 2015), the US Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that 1 in 4 of the US workforce will be 55 or over. Workers may have good reason to avoid retirement, although it is often viewed as a time of relaxation and well-earned rest, statistics may indicate that a continued focus on the future may be preferable to stasis, or inactivity. In fact, Fitzpatrick & Moore (2018) report that death rates for American males jump 2% immediately after they turn 62, most likely a result of changes induced by retirement. Interestingly, this small spike in death rates is not seen in women, which may be the result of women having stronger social determinants of health (SDOH), which keep them active and interacting with others out of retirement.

What you’ll learn to do: explain how relationships are maintained and changed during middle adulthood

The importance of establishing and maintaining relationships in middle adulthood is now well established in the academic literature—there are now thousands of published articles purporting to demonstrate that social relationships are integral to any and all aspects of subjective well-being and physiological functioning, and these help to inform actual healthcare practices. Studies show an increased risk of dementia, cognitive decline, susceptibility to vascular disease, and increased mortality in those who feel isolated and alone. However, loneliness is not confined to people living a solitary existence. It can also refer to those who endure a perceived discrepancy in the socio-emotional benefits of interactions with others, either in number or nature. One may have an expansive social network and still feel a dearth of emotional satisfaction in one’s own life.

Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST) predicts a quantitative decrease in the number of social interactions in favor of those bringing greater emotional fulfillment. Over the past thirty years, or more, significant social changes have, in turn, had a large effect on human bonding. These have affected the way we manage our emotional interactions, and the manner in which society views, shapes and supports that emotional regulation. Government policy has also changed and profoundly influenced how families are shaped, reshaped, and operate as social and economic agents.

Learning outcomes

- Describe the link between intimacy and subjective well-being

- Discuss issues related to family life in middle adulthood

- Discuss divorce and recoupling during middle adulthood

Relationships and Family Life in Middle Adulthood

Types of Relationships

Intimate Relationships

It makes sense to consider the various types of relationships in our lives when determining how relationships impact our well-being. For example, would you expect a person to derive the same happiness from an ex-spouse as from a child or coworker? Among the most important relationships for most people is their long-time romantic partner. Most researchers begin their investigation of this topic by focusing on intimate relationships because they are the closest form of a social bond. Intimacy is more than just physical in nature; it also entails psychological closeness. Research findings suggest that having a single confidante—a person with whom you can be authentic and trust not to exploit your secrets and vulnerabilities—is more important to happiness than having a large social network (Taylor, 2010).

Another important aspect of relationships is the distinction between formal and informal. Formal relationships are those that are bound by the rules of politeness. In most cultures, for instance, young people treat older people with formal respect, avoiding profanity and slang when interacting with them. Similarly, workplace relationships tend to be more formal, as do relationships with new acquaintances. Formal connections are generally less relaxed because they require a bit more work, demanding that we exert more self-control. Contrast these connections with informal relationships—friends, lovers, siblings, or others with whom you can relax. We can express our true feelings and opinions in these informal relationships, using the language that comes most naturally to us, and generally, be more authentic. Because of this, it makes sense that more intimate relationships—those that are more comfortable and in which you can be more vulnerable—might be the most likely to translate to happiness.

Marriage and Happiness

One of the most common ways that researchers often begin to investigate intimacy is by looking at marital status. The well-being of married people is compared to that of people who are single or have never been married. In other research, married people are compared to people who are divorced or widowed (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2005). Researchers have found that the transition from singlehood to marriage increases subjective well-being (Haring-Hidor et al., 1985; Lucas, 2005; Williams, 2003). In fact, this finding is one of the strongest in social science research on personal relationships over the past quarter of a century.

As is usually the case, the situation is more complex than might initially appear. As a marriage progresses, there is some evidence for a regression to a hedonic set-point—that is, most individuals have a set happiness point or level, and that both good and bad life events – marriage, bereavement, unemployment, births, and so on – have some effect for a period of time, but over many months, they will return to that set-point. One of the best studies in this area is that of Luhmann et al. (2012), who report a gradual decline in subjective well-being after a few years, especially in the component of affective well-being. Adverse events obviously have an effect on subjective well-being and happiness, and these effects can be stronger than the positive effects of being married in some cases (Lucas, 2005).

Although research frequently points to marriage being associated with higher rates of happiness, this does not guarantee that getting married will make you happy! The quality of one’s marriage matters greatly. It takes an emotional toll when a person remains in a problematic marriage. Indeed, a large body of research shows that people’s overall life satisfaction is affected by their satisfaction with their marriage (Carr, Freedman, Cornman, Schwarz, 2014; Dush, Taylor, & Kroeger, 2008; Karney, 2001; Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid, & Lucas, 2012; Proulx, Helms, & Buehler, 2007). The lower a person’s self-reported level of marital quality, the more likely he or she is to report depression (Bookwala, 2012). In fact, longitudinal studies—those that follow the same people over a period of time—show that as marital quality declines, depressive symptoms increase (Fincham, Beach, Harold, & Osborne, 1997; Karney, 2001). Proulx and colleagues (2007) reached this conclusion after a systematic review of 66 cross-sectional and 27 longitudinal studies.

Marital satisfaction has peaks and valleys during the course of the life cycle. Rates of happiness are highest in the years prior to the birth of the first child. It hits a low point with the coming of children. Relationships typically become more traditional, and living has more financial hardships and stress. Children bring new expectations to the marital relationship. Two people who are comfortable with their roles as partners may find the added parental duties and expectations more challenging to meet. Some couples elect not to have children in order to have more time and resources for the marriage. These child-free couples are happy keeping their time and attention on their partners, careers, and interests.

What is it about bad marriages or bad relationships in general, that takes such a toll on well-being? Research has pointed to the conflict between partners as a major factor leading to lower subjective well-being (Gere & Schimmack, 2011). This makes sense. Negative relationships are linked to ineffective social support (Reblin, Uchino, & Smith, 2010) and are a source of stress (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2007). In more extreme cases, physical and psychological abuse can harm well-being (Follingstad, Rutledge, Berg, Hause, & Polek, 1990). Victims of abuse sometimes feel shame, lose their sense of self, and become less happy and prone to depression and anxiety (Arias & Pape, 1999). However, the unhappiness and dissatisfaction that occur in abusive relationships tend to dissipate once the relationships end. (Arriaga, Capezza, Goodfriend, Rayl & Sands, 2013).

Typology of Marriage

One way marriages vary is with regard to the reason the partners are married. Some marriages have intrinsic value: the partners are together because they enjoy, love, and value one another. Marriage is not considered a means to another end; instead, it is regarded as an end. These partners look for someone they are drawn to, and with whom they feel a close and intense relationship. Other marriages called utilitarian marriages, are unions entered into primarily for practical reasons. For example, the marriage brings financial security, children, social approval, housekeeping, political favor, a good car, a great house, and so on.

There have been a few attempts to establish a typological framework for marriages. The best-known is that of Olson (1993), who referred to five typical kinds of marriage. Using a sample of 6,267 couples, Olson & Fowers (1993) identified eleven relationship domains which covered both areas related to relationship satisfaction and the more functional areas related to marriage. So, five of the eleven included areas such as marital satisfaction, communication, and, things like financial management, parenting, and egalitarian roles. Using these eleven areas they came up with five kinds of marriage. One aspect of this early study is the link between marital satisfaction and income/college education. The link between these factors is now commonplace in the literature. Olson & Fowers (1993) were one of the first studies to point to this link. The less well-off are more prone to divorce than those with less college-level education. Income and college education are linked, and there is increasing concern that marital dissolution and broader social inequality patterns are inextricably linked.

- vitalized: Very high relationship quality. Tend to belong in a higher income bracket. Happy with their spouse across all areas: personality, communication, roles, and expectations.

- harmonious relationships: These marriages have some areas of tension and disagreement but there is still broad agreement on major issues. Lack of agreement on parenting was the primary feature of this group, although the couples still scored highly on relationship quality.

- traditional marriages: Much less emphasis on emotional closeness, but still slightly above average. High levels of compatibility in relation to parenting.

- conflicted: These marriages accomplish functional goals such as parenting but are marked by a great deal of interpersonal disagreement. Communication and conflict resolution scores are extremely low.

- devitalized: low scores across all eleven areas – Little interpersonal closeness and little agreement on family roles.

Marital Communication

Advice on how to improve one’s marriage is centuries old. One of today’s experts on marital communication is John Gottman. Gottman differs from many marriage counselors in his belief that having a good marriage does not depend on compatibility, rather, the way that partners communicate with one another is crucial. At the University of Washington in Seattle, Gottman has measured the physiological responses of thousands of couples as they discuss issues that have led to disagreements. Fidgeting in one’s chair, leaning closer to or further away from the partner while speaking, and increases in respiration and heart rate are all recorded and analyzed, along with videotaped recordings of the partners’ exchanges.