Death and Grief

This text was last updated as of January 16, 2023 and is no longer being maintained by the author. The current version Psychology Through the Lifespan is available for use.

Why learn about experiences and emotions related to death and dying?

A dying process that allows an individual to make choices about treatment, to say goodbyes, and to take care of final arrangements is what many people hope for. Such a death might be considered a “good death.” But of course, many deaths do not occur in this way. Not all deaths include such a dialogue with family members or being able to die in familiar surroundings; people may die suddenly and alone or leave home and never return. Children sometimes precede parents in death; wives precede husbands, and the homeless are bereaved by strangers.

In this module, we will look at death and dying, grief and bereavement, palliative care, and hospice to understand these last stages of life better.

While death has always been a universal component in the human experience, its prevalence and circumstances have changed over the years. Today, we associate death with the elderly, but looking back even one hundred years ago, death was more common among children and in various age ranges. At that time, it was not uncommon for American families to lose a child during childbirth or infancy. Today less than 10% of all deaths worldwide occur to children under the age of 5, but as recently as 1990, that number was nearly 25%.

The graph above shows data from 2016, which reveals that nearly half of the 55 million global deaths occurred to those aged 70 years or older. There is still a great amount of disparity in death statistics based on location and access to medical care. In the United States, for example, deaths in that same age group of 70 years old or older accounted for 65% of total deaths. In this section, we’ll look more closely at the leading causes of death in the United States and throughout the globe.

Learning outcomes

- Examine the leading causes of death in the United States and worldwide

- Explain physiological death

- Describe social and psychological death

Most Common Causes of Death

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, based on the year of birth, current age, and other demographic factors including gender. The most commonly used measure of life expectancy is at birth (LEB). There are great variations in life expectancy in different parts of the world, mostly due to differences in public health, medical care, and diet, but also affected by education, economic circumstances, violence, mental health, and sex.

Life Expectancy in the United States

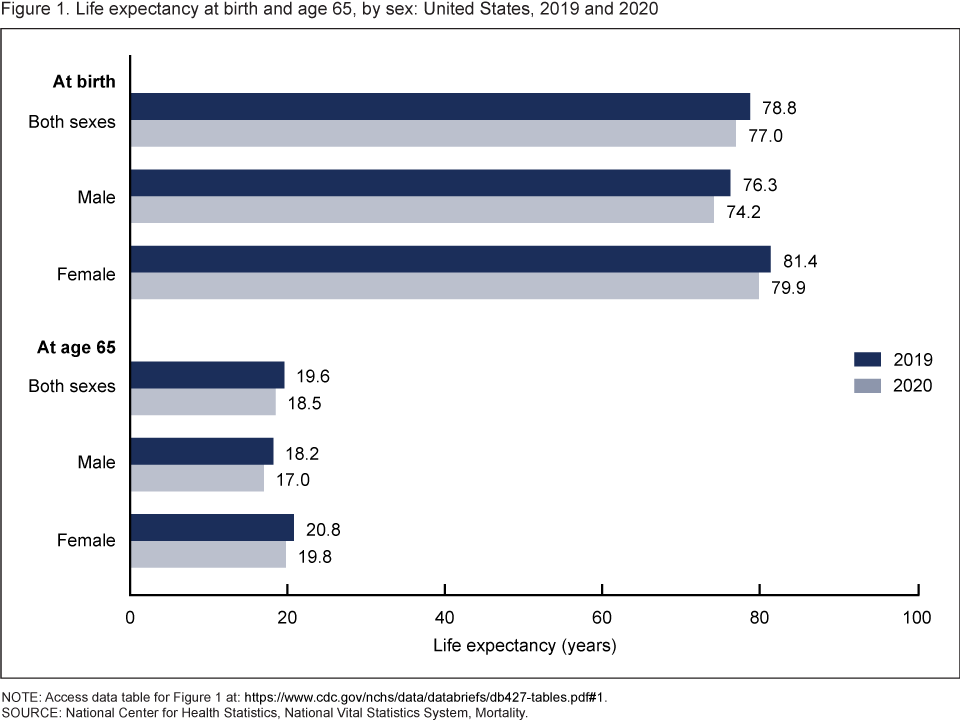

According to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), in 2020, life expectancy at birth was 77.0 years for the total U.S. population—a decrease of 1.8 years from 78.8 years in 2019. For males, life expectancy decreased 2.1 years from 76.3 in 2019 to 74.2 in 2020. For females, life expectancy decreased 1.5 years from 81.4 in 2019 to 79.9 in 2020. In 2020, the difference in life expectancy between females and males was 5.7 years, an increase of 0.6 year from 2019.

In 2020, life expectancy at age 65 for the total population was 18.5 years, a decrease of 1.1 years from 2019. For males, life expectancy at age 65 decreased 1.2 years from 18.2 in 2019 to 17.0 in 2020. For females, life expectancy at age 65 decreased 1.0 year from 20.8 in 2019 to 19.8 in 2020. The difference in life expectancy at age 65 between females and males increased 0.2 year, from 2.6 years in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020.

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010–an increase of 5400%!

Statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau reveal that the 85-and over age group is the fastest-growing age group in America. According to the Census Bureau and AgingStats.gov, the over-65 population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 40 million in 2010, an increase of more than 1200%. But during this same time, the over-85 population grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.5 million in 2010–an increase of 5400%!

When calculating life expectancy, we consider all of the elements of heredity, health history, current health habits, and current life experiences which contribute to a longer life or subtract from a person’s life expectancy. Recent studies concluded that cutting calorie intake by 15 percent over two years can slow aging and protect against diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s (Redman et al., 2018).

Some life factors are beyond a person’s control, and some are controllable. The rising cost of health care is a source of financial vulnerability to older adults. Vaccines are especially important for older adults. As you get older you’re more likely to get diseases like the flu, pneumonia, and shingles, and to have complications that can lead to long-term illness, hospitalization, and even death.

Things that contribute to longer life expectancies include eating a healthy diet that is rich in plants and nuts. Staying physically active, not smoking, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol, tea, or coffee are also reported to be beneficial to leading a long life. Other recommendations include being conscientious, prioritizing your happiness, avoiding stress and anxiety, and having a strong social support network. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and maintaining between 7-8 hours of sleep per night is also beneficial (Petre, 2019).

A person will statistically live longer once they reach an older age because they have made it this far without anything killing them. Also, there appear to be several factors that may explain changes in life expectancy in the United States and around the world—health conditions are better, many diseases have been eliminated or better controlled through medicine, working conditions are better and better lifestyle choices are being made. Such factors significantly contribute to longer life expectancies.

Understanding Life Expectancy

Life expectancy is also used in describing the physical quality of life. Quality of life is the general well-being of individuals and societies, outlining negative and positive features of life. Quality of life considers life satisfaction, including everything from physical health, family, education, employment, wealth, safety, security, freedom, religious beliefs, and the environment.

Increased life expectancy brings concern over the health and independence of those living longer. Greater attention is now being given to the number of years a person can expect to live without disability, which is called active life expectancy. When this distinction is made, we see that although women live longer than men, they are more at risk of living with a disability (Weitz, 2007).

What factors contribute to poor health in women? Marriage has been linked to longevity, but spending years in a stressful marriage can increase the risk of illness. This negative effect is experienced more by women than men and seems to accumulate over the years. The impact of a stressful marriage on health may not occur until a woman reaches 70 or older (Umberson et al., 2006). Sexism can also create chronic stress. The stress experienced by women as they work outside the home and care for family members can ultimately negatively impact health (He et al., 2005).

The shorter life expectancy for men in general, is attributed to greater stress, poorer attention to health, more involvement in dangerous occupations, and higher rates of death due to accidents, homicide, and suicide. Social support can increase longevity. For men, life expectancy and health seems to improve with marriage. Spouses are less likely to engage in risky health practices and wives are more likely to monitor their husband’s diet and health regimes. But men who live in stressful marriages can also experience poorer health as a result.

The United States

In 1900, the most common causes of death were infectious diseases, which brought death quickly. Due to advances in healthcare and medicine over the years, this has changed, alongside an increase in average life expectancy. In modern times, chronic diseases, or those in which a slow and steady decline causes health deterioration, are more common. How might this impact the way we think of death, the way we grieve, and the amount of control a person has over his or her own dying process, in comparison to the infectious diseases that were prevalent in 1900?

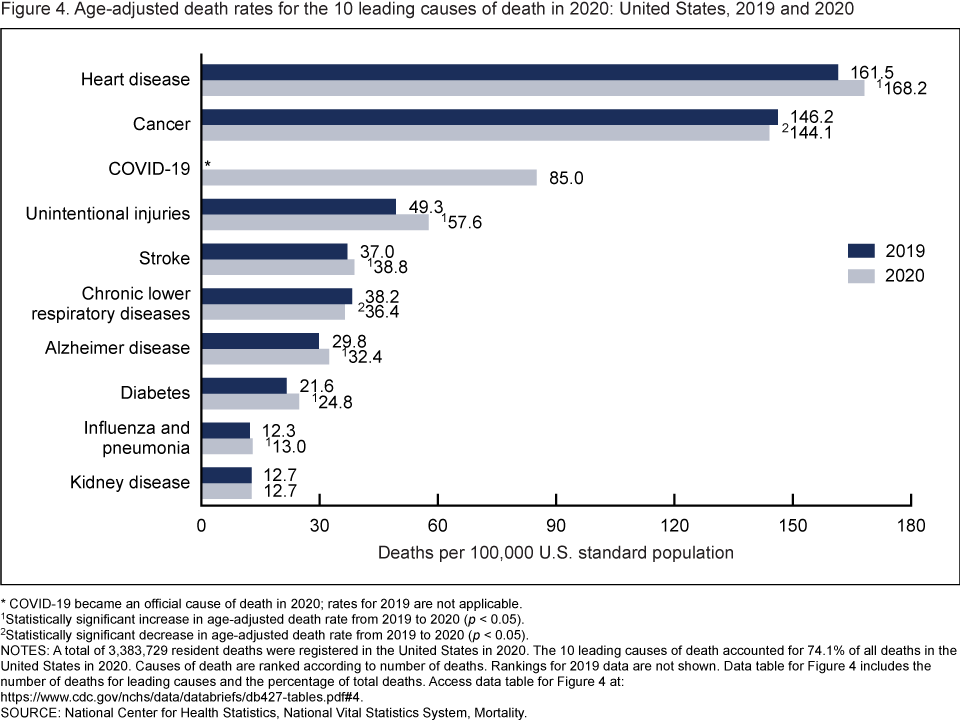

In 2020, 9 of the 10 leading causes of death remained the same as in 2019. The top leading cause was heart disease, followed by cancer. COVID-19, newly added as a cause of death in 2020, became the 3rd leading cause of death. Of the remaining leading causes in 2020 (unintentional injuries, stroke, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer disease, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia, and kidney disease), 5 causes changed ranks from 2019. Unintentional injuries, the 3rd leading cause in 2019, became the 4th leading cause in 2020. Chronic lower respiratory diseases, the 4th leading cause in 2019, became the 6th. Alzheimer disease, the 6th leading cause in 2019, became the 7th. Diabetes, the 7th leading cause in 2019, became the 8th. Kidney disease, the 8th leading cause in 2019, became the 10th leading cause in 2020. Stroke, and influenza and pneumonia, remained the 5th and 9th leading causes, respectively (1). Suicide dropped from the list of 10 leading causes in 2020. Causes of death are ranked according to number of deaths (1). The 10 leading causes accounted for 74.1% of all deaths in the United States in 2020.

From 2019 to 2020, age-adjusted death rates increased for 6 of 10 leading causes of death and decreased for 2. The rate increased 4.1% for heart disease (from 161.5 in 2019 to 168.2 in 2020), 16.8% for unintentional injuries (49.3 to 57.6), 4.9% for stroke (37.0 to 38.8), 8.7% for Alzheimer disease (29.8 to 32.4), 14.8% for diabetes (21.6 to 24.8), and 5.7% for influenza and pneumonia (12.3 to 13.0). Rates decreased 1.4% for cancer (146.2 to 144.1) and 4.7% for chronic lower respiratory diseases (38.2 to 36.4). The rate for kidney disease remained unchanged.

Data comparisons from 2019 to 2020 for COVID-19 are not applicable because COVID-19 was a new cause in 2020.

Deadliest Diseases Worldwide

In 2019, the top 10 causes of death accounted for 55% of the 55.4 million deaths worldwide (WHO, 2020). The top global causes of death, in order of the total number of lives lost, are associated with three broad topics: cardiovascular (ischaemic heart disease, stroke), respiratory (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lower respiratory infections), and neonatal conditions – which include birth asphyxia and birth trauma, neonatal sepsis and infections, and preterm birth complications.

Causes of death can be grouped into three categories: communicable (infectious and parasitic diseases and maternal, perinatal, and nutritional conditions), noncommunicable (chronic), and injuries. Notice there are several similarities between these and the top 10 causes of death in the United States described above.

Why do we need to know the reasons people die?

It is important to know why people die to improve how people live (WHO, 2020). Measuring how many people die each year helps to assess the effectiveness of our health systems and direct resources to where they are needed most. For example, mortality data can help focus activities and resource allocation among sectors such as transportation, food and agriculture, and the environment as well as health.

COVID-19 has highlighted the importance for countries to invest in civil registration and vital statistics systems to allow daily counting of deaths, and direct prevention and treatment efforts. It has also revealed inherent fragmentation in data collection systems in most low-income countries, where policy-makers still do not know with confidence how many people die and of what causes.

A Comparison of Death by Age in the United States

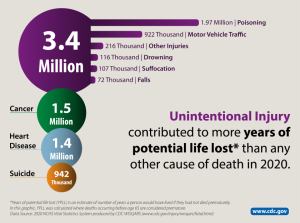

The major causes of death vary significantly among age groups. As you can see in Figure 1, congenital diseases and accidents are major causes of death among children, then accidents and suicides are the leading causes of death between ages 10 and 24. This changes again and late adulthood, as heart disease and cancer combined cause over 50% of deaths for those aged between 45 and 65. into middle and late adulthood, as heart disease and cancer combined cause over 50% of deaths for those aged between 45 and 65. Notice that unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for the widest variety of ages. Review the Top 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group in 2020

Death and The Media

Interestingly, the things that actually result in death are not often the things we hear about on the news. Because of the availability heuristic—a cognitive shortcut in which people rely heavily on information that is most readily available in their mind, people may erroneously be more afraid of sensational deaths than death by more normal causes, such as heart disease.

The Process of Dying

Aspects of Death

One way to understand death and dying is to look more closely at physiological, social, and psychological death. These deaths do not occur simultaneously, nor do they always occur in a set order. Rather, a person’s physiological, social, and psychological deaths can occur at different times (Butow, 2017).

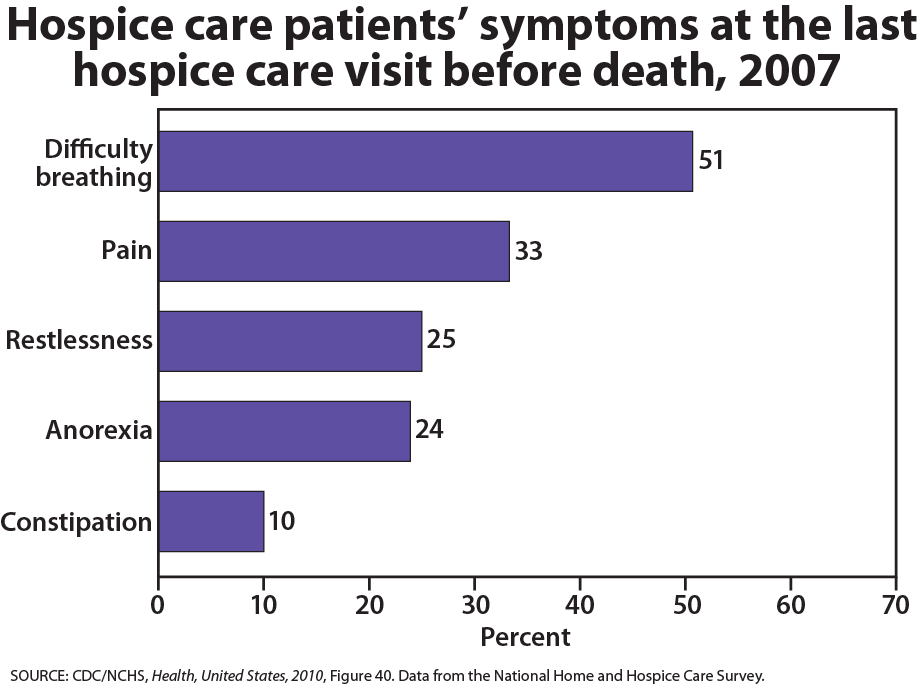

Physiological death occurs when the vital organs no longer function. The digestive and respiratory systems begin to shut down during the gradual process of dying. A dying person no longer wants to eat as digestion slows, the digestive track loses moisture, and chewing, swallowing, and elimination become painful processes. Circulation slows and mottling, or the pooling of blood, may be noticeable on the underside of the body, appearing much like bruising. Breathing becomes more sporadic and shallow and may make a rattling sound as air travels through mucus-filled passageways. Agonal breathing refers to gasping, labored breaths caused by an abnormal pattern of brainstem reflex. The person often sleeps more and more and may talk less, although they may continue to hear. The kinds of symptoms noted prior to death in patients under hospice care (care focused on helping patients die as comfortably as possible) are noted below.

When a person is brain dead or no longer has brain activity, they are clinically dead. Physiological death may take 72 or fewer hours. This is different from a vegetative state, which occurs when the cerebral cortex no longer registers electrical activity but the brain stems continue to be active. Individuals who are kept alive through life support may be classified this way.

Social death begins much earlier than physiological death. Social death occurs when others begin to withdraw from someone who is terminally ill or has been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Those diagnosed with conditions such as AIDS or cancer may find that friends, family members, and even health care professionals begin to say less and visit less frequently. Meaningful discussions may be replaced with comments about the weather or other topics of light conversation. Doctors may spend less time with patients after their prognosis becomes poor. Why do others begin to withdraw? Friends and family members may feel that they do not know what to say or that they can offer no solutions to relieve suffering. They withdraw to protect themselves against feeling inadequate or from having to face the reality of death. Health professionals, trained to heal, may also feel inadequate and uncomfortable facing decline and death. A patient who is dying may be referred to as “circling the drain,” meaning that they are approaching death. People in nursing homes may live as socially dead for years with no one visiting or calling. Social support is important for quality of life and those who experience social death are deprived of the benefits that come from loving interaction with others.

Psychological death occurs when the dying person begins to accept death and to withdraw from others and regress into the self. This can take place long before physiological death (or even social death if others are still supporting and visiting the dying person) and can even bring physiological death closer. People have some control over the timing of their death and can hold on until after important occasions or die quickly after having lost someone important to them. In some cases, individuals can give up their will to live. This is often at least partially attributable to a lost sense of identity. The individual feels consumed by the reality of making final decisions, planning for loved ones—especially children, and coping with the process of his or her own physical death.

Interventions based on the idea of self-empowerment enable patients and families to identify and ultimately achieve their own goals of care, thus producing a sense of empowerment. Self-empowerment for terminally ill individuals has been associated with a perceived ability to manage and control things such as medical actions, changing life roles, and the psychological impacts of the illness (Butow, 2017).

Treatment plans that are able to incorporate a sense of control and autonomy into the dying individual’s daily life have been found to be particularly effective in regards to general attitude as well as depression level. For example, it has been found that when dying individuals are encouraged to recall situations from their lives in which they were active decision-makers, explored various options, and took action, they tend to have better mental health than those who focus on themselves as victims. Similarly, there are several theories of coping that suggest active coping (seeking information, working to solve problems) produces more positive outcomes than passive coping (characterized by avoidance and distraction). Although each situation is unique and depends at least partially on the individual’s developmental stage, the general consensus is that it is important for caregivers to foster a supportive environment and partnership with the dying individual, which promotes a sense of independence, control, and self-respect.

What you’ll learn to do: examine care and practices related to death

In this section, we’ll turn our attention from the process of dying to the actual death of the individual. We’ll examine various ways in which deliberate death can occur, along with the supportive practices that are available for those who are dying. We will also take a closer look at cultural and legal implications of end-of-life practices.

Learning outcomes

- Explain the philosophy and practice of palliative care

- Describe hospice care

- Summarize Dame Cicely Saunders’ writings about total pain of the dying

- Differentiate attitudes toward hospice care based on race and ethnicity

- Describe and contrast types of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide

Palliative Care and Hospice

Palliative Care

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary approach to specialized medical and nursing care for people with life-limiting illnesses. It focuses on providing relief from the symptoms, pain, physical stress, and mental stress at any stage of illness, with a goal of improving the quality of life for both the person and their family. Doctors who specialize in palliative care have had training tailored to helping patients and their family members cope with the reality of the impending death and make plans for what will happen after (National Institute on Aging, 2019).

Palliative care is provided by a team of physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and other health professionals who work together with the primary care physician and referred specialists or other hospital or hospice staff to provide additional support to the patient. It is appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided as the main goal of care or along with curative treatment. Although it is an important part of end-of-life care, it is not limited to that stage. Palliative care can be provided across multiple settings including in hospitals, at home, as part of community palliative care programs, and in skilled nursing facilities. Interdisciplinary palliative care teams work with people and their families to clarify goals of care and provide symptom management, psychosocial, and spiritual support.

Hospice

In many other countries, no distinction is made between palliative care and hospice, but in the United States, the terms have different meanings and usages. They both share similar goals of providing symptom relief and pain management, but hospice care is a type of care involving palliation without curative intent. Usually, it is used for people with no further options for curing their disease or for people who have decided not to pursue further options that are arduous, likely to cause more symptoms, and not likely to succeed. The biggest difference between hospice and palliative care is the type of illness people have, where they are in their illness especially related to prognosis, and their goals/wishes regarding curative treatment. Hospice care under the Medicare Hospice Benefit requires that two physicians certify that a person has less than six months to live if the disease follows its usual course. This does not mean, though, that if a person is still living after six months in hospice he or she will be discharged from the service.

Hospice care involves caring for dying patients by helping them be as free from pain as possible, providing them with assistance to complete wills and other arrangements for their survivors, giving them social support through the psychological stages of loss, and helping family members cope with the dying process, grief, and bereavement. It focuses on five topics: communication, collaboration, compassionate caring, comfort, and cultural (spiritual) care. Most hospice care does not include medical treatment of disease or resuscitation although some programs administer curative care as well. The patient is allowed to go through the dying process without invasive treatments. Family members who have agreed to put their loved one on hospice may become anxious when the patient begins to experience death. They may believe that feeding or breathing tubes will sustain life and want to change their decision. Hospice workers try to inform the family of what to expect and reassure them that much of what they see is a normal part of the dying process.

The History of Hospice

Dame Cicely Saunders was a British registered nurse whose chronic health problems had forced her to pursue a career in medical social work. The relationship she developed with a dying Polish refugee helped solidify her ideas that terminally ill patients needed compassionate care to help address their fears and concerns as well as palliative comfort for physical symptoms. After the refugee’s death, Saunders began volunteering at St Luke’s Home for the Dying Poor, where a physician told her that she could best influence the treatment of the terminally ill as a physician. Saunders entered medical school while continuing her volunteer work at St. Joseph’s. When she achieved her degree in 1957, she took a position there.

Saunders emphasized focusing on the patient rather than the disease and introduced the notion of ‘total pain’, which included psychological, spiritual, emotional, intellectual, and interpersonal aspects of pain, the physical aspects, and even financial and bureaucratic aspects. This focus on the broad effects of death on dying individuals and their families has provided the foundation for modern-day practices related to hospice care services (Richmond, 2005). Saunders experimented with a wide range of opioids for controlling physical pain but also considered the needs of the patient’s family.

Saunders disseminated her philosophy internationally in a series of tours of the United States that began in 1963. In 1967, Saunders opened St. Christopher’s Hospice. Florence Wald, the Dean of Yale School of Nursing who had heard Saunders speak in America, spent a month working with Saunders there in 1969 before bringing the principles of modern hospice care back to the United States, establishing Hospice, Inc. in 1971. Another early hospice program in the United States, Alive Hospice, was founded in Nashville, Tennessee in 1975. By 1977 the National Hospice Organization had been formed.

Hospice Care in Practice

The early established hospices were independently operated and dedicated to giving patients as much control over their own death process as possible. Today, it is estimated that over 40 million individuals require palliative care, with over 78% of them being of low-income status or living in low-income countries (World Health Organization, 2019). It is also estimated, however, that less than 14% of these individuals receive it. This gap is created by restrictive regulatory laws regarding controlled substance medications for pain management, as well as a general lack of adequate training in regards to palliative care within the health professional community. Although hospice care has become more widespread, these new programs are subjected to more rigorous insurance guidelines that dictate the types and amounts of medications used, length of stay, and types of patients who are eligible to receive hospice care. Thus, more patients are being served, but providers have less control over the services they provide, and lengths of stay are more limited. Patients receive palliative care in hospitals and in their homes.

The majority of patients on hospice are cancer patients and they typically do not enter hospice until the last few weeks prior to death. The average length of stay is less than 30 days and many patients are on hospice for less than a week (World Health Organization, 2019). Medications are rubbed into the skin or given in drop form under the tongue to relieve the discomfort of swallowing pills or receiving injections. A hospice care team includes a chaplain as well as nurses and grief counselors to assist spiritual needs in addition to physical ones. When hospice is administered at home, family members may also be part, and sometimes the biggest part, of the care team. Certainly, being in familiar surroundings is preferable to dying in an unfamiliar place. But about 60 to 70 percent of people die in hospitals and another 16 percent die in institutions such as nursing homes. Most hospice programs serve people over 65; few programs are available for terminally ill children.

Hospice care focuses on alleviating physical pain and providing spiritual guidance. Those suffering from Alzheimer’s also experience intellectual pain and frustration as they lose their ability to remember and recognize others. Depression, anger, and frustration are elements of emotional pain, and family members can have tensions that a social worker or clergy member may be able to help resolve. Many patients are concerned with the financial burden their care will create for family members. And bureaucratic pain is also suffered while trying to submit bills and get information about health care benefits or to complete requirements for other legal matters. All of these concerns can be addressed by hospice care teams.

The Hospice Foundation of America notes that not all racial and ethnic groups feel the same way about hospice care. Certain groups may believe that medical treatment should be pursued on behalf of an ill relative as long as possible and that only God can decide when a person dies. Others may feel very uncomfortable discussing issues of death or being near the deceased family member’s body. The view that hospice care should always be used is not held by everyone and health care providers need to be sensitive to the wishes and beliefs of those they serve. Similarly, the population of individuals using hospice services is not divided evenly by race. Approximately 81% of hospice patients are White, while 8.7% are African American, 8.7% are multiracial, 1.9% are Pacific Islander, and only 0.2% are Native American (Campbell et al., 2014).

Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide

Euthanasia, or helping a person fulfill their wish to die, can happen in two ways: voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Voluntary euthanasia refers to helping someone fulfill their wish to die by acting in such a way to help that person’s life end. This can be passive euthanasia such as no longer feeding someone or giving them food. Or it can be active euthanasia such as administering a lethal dose of medication to someone who wishes to die. In some cases, a dying individual who is in pain or constant discomfort will ask this of a friend or family member, as a way to speed up what he or she has already accepted as being inevitable. This can have lasting effects on the individual or individuals asked to help, including but not limited to prolonged (Meier et al., 2009).

Physician-Assisted Suicide: Physician-assisted suicide occurs when a physician prescribes the means by which a person can end his or her own life. This differs from euthanasia, in that it is mandated by a set of laws and is backed by legal authority. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in the District of Columbia and several states, including Oregon, Hawaii, Vermont, and Washington. It is also legal in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium.

What Do You Think?

What would you do if your spouse or loved one was declared brain dead but his or her body was being kept alive by medical equipment? Whose decision should it be to remove a feeding tube? Should medical care costs be a factor?

On February 25, 1990, a Florida woman named Terri Schiavo went into cardiac arrest, apparently triggered by a bulimic episode. She was eventually revived, but her brain had been deprived of oxygen for a long time. Brain scans indicated that there was no activity in her cerebral cortex, and she suffered from severe and permanent cerebral atrophy. Basically, Schiavo was in a vegetative state. Medical professionals determined that she would never again be able to move, talk, or respond in any way. She required a feeding tube to remain alive, and there was no chance that her situation would ever improve.

On occasion, Schiavo’s eyes would move, and sometimes she would groan. Despite the doctors’ insistence to the contrary, her parents believed that these were signs that she was trying to communicate with them.

After 12 years, Schiavo’s husband argued that his wife would not have wanted to be kept alive with no feelings, sensations, or brain activity. Her parents, however, were very much against removing her feeding tube. Eventually, the case made its way to the courts, both in the state of Florida and at the federal level. By 2005, the courts found in favor of Schiavo’s husband, and the feeding tube was removed on March 18, 2005. Schiavo died 13 days later.

Why did Schiavo’s eyes sometimes move, and why did she groan? Although the parts of her brain that control thought, voluntary movement, and feeling were completely damaged, her brainstem was still intact. Her medulla and pons maintained her breathing and caused involuntary movements of her eyes and the occasional groans. Over the 15-year period that she was on a feeding tube, Schiavo’s medical costs may have topped $7 million (Arnst, 2003).

These questions were brought to popular conscience decades ago in the case of Terri Schiavo, and they have persisted. In 2013, a 13-year-old girl who suffered complications after tonsil surgery was declared brain dead. There was a battle between her family, who wanted her to remain on life support, and the hospital’s policies regarding persons declared brain dead. In another complicated 2013–14 case in Texas, a pregnant EMT professional declared brain dead was kept alive for weeks, despite her spouse’s directives, which were based on her wishes should this situation arise. In this case, state laws designed to protect an unborn fetus came into consideration until doctors determined the fetus unviable.

Decisions surrounding the medical response to patients declared brain dead are complex. What do you think about these issues?

The specific laws that govern the practice of physician-assisted suicide vary between states. Oregon, Vermont, and Washington, for example, require the prescription to come from either a Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) or a Doctor of Osteopathy (D.O.) (Theil-Reiter et al., 2018). These state laws also include a clause about the designated medical practitioner being willing to participate in this act. In Colorado, terminally ill individuals have the option to request and self-administer life-ending medication if their medical prognosis gives them six months or less to live. In the District of Columbia and Hawaii, the individual must make two requests within predefined periods of time and complete a waiting period, and in some cases undergo additional evaluations before the medication can be provided.

A growing number of the population support physician-assisted suicide. In 2000, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling upheld states’ right to determine their laws on physician-assisted suicide despite efforts to limit physicians’ ability to prescribe barbiturates and opiates for their patients requesting the means to end their lives. The position of the Supreme Court is that the debate concerning the morals and ethics surrounding the right to die is one that should be continued. As an increasing number of the population enters late adulthood, the emphasis on giving patients an active voice in determining certain aspects of their own death is likely.

Physician-Assisted Suicide

In a recent example of physician-assisted death, David Goodall, a 104-year-old professor, ended his life by choice in a Swiss clinic in May 2018. Having spent his life in Australia, Goodall traveled to Switzerland to do this, as the laws in his country do not allow for it. Swiss legislation does not openly permit physician-assisted suicide, but it does not forbid an individual with “commendable motives” from assisting another person in taking his or her own life. Watch this video of a news conference with Goodall “104-year-old Australian Promotes Right to Assisted Suicide” that took place the day before he ended his life with physician-assisted suicide.

Another public advocate for physician-assisted suicide and death with dignity was 29-year old Brittany Maynard, who after being diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, decided to move to Oregon so that she could end her life with physician-assisted suicide. You can watch this video “The Brittany Maynard Story” to learn more about Brittany’s story.

Death is something we all must face at some point. It occurs on physiological, psychological, and social levels, each of which has unique implications for the dying individuals and those close to them. Physiological death occurs as the body ceases to function, eventually rendering the individual unable to engage in necessary basic processes, such as breathing and eating. Psychological death occurs when the individual begins to face his or her impending death and consequently regresses into the self. Societal death occurs when others withdraw from the individual, perhaps unable to cope with the impending loss and its implications effectively.

In some cases, palliative care or hospice services assist the dying individual and their family throughout the dying process. These services include care for the dying individual, as well as support for the family. In addition, several states allow terminally ill or dying individuals to utilize physician-assisted suicide, in which a medical practitioner prescribes and/or administers life-ending medication at the individual’s request. The utilization of palliative or hospice care services, as well as physician-assisted suicide, vary between individuals, cultures, and racial groups, ultimately reflecting the legal, ethical, and moral complexity of both types of practices.

The way in which we view death, talk about it, prepare for it, and what we do when it happens vary both within and between cultures. Coping with the grief associated with death and loss is a complex but necessary process, with several strategies for working through the situation in a healthy and positive way. Several theories have been created to explain how grieving happens, some including stages of grief that the individual experiences, others including tasks that the individual must complete. These stages and tasks on their own are neutral, with the potential to facilitate positive coping, but can also become maladaptive if the individual does not healthily work through them. Death is ultimately the end of lifespan development, which occurs for everyone at some time. It is the culmination of the other stages of development, many of which play a role in shaping how the individual handles death when the time comes, both for the self and for loved ones.

What you’ll learn to do: examine emotions related to death and dying

While death is inevitable, our emotional responses and reactions to it vary dramatically. In this section, we’ll take a closer look at the emotions that are involved in death, both for the individual who is dying as well as their family and friends. We’ll also learn more about the stages of grief and how to cope with death.

Learning outcomes

- Explain common perceptions and attitudes toward death

- Explain bereavement and types of grief

- Explain Kübler-Ross’ stages of loss

- List and describe the stages of grief based on various models

Attitudes about Death

Bereavement refers to outward expressions of grief. Mourning and funeral rites are expressions of loss that reflect personal and cultural beliefs about the meaning of death and the afterlife. When asked what type of funeral they would like to have, students responded in various ways, expressing their personal beliefs and values and those of their culture.

I would like the service to be at a Baptist church, preferably my Uncle Ike’s small church. The service should be a celebration of life . . .I would like there to be hymns sung by my family members, including my favorite one, “It is Well With my Soul”. . .At the end, I would like the message of salvation to be given to the attendees and an alter call for anyone who would like to give their life to Christ. . .

I want a very inexpensive funeral-the bare minimum, only one vase of flowers, no viewing of the remains and no long period of mourning from my remaining family . . . funeral expenses are extremely overpriced and out of hand. . .

When I die, I would want my family members, friends, and other relatives to dress my body as it is usually done in my country, Ghana. Lay my dressed body in an open space in my house at the night prior to the funeral ceremony for my loved ones to walk around my body and mourn for me. . .

I would like to be buried right away after I die because I don’t want my family and friends to see my dead body and to be scared.

In my family, we have always had the traditional ceremony-coffin, grave, tombstone, etc. But I have considered cremation and still ponder which method is more favorable. Unlike cremation, when you are ‘buried’ somewhere and family members have to make a special trip to visit, cremation is a little more personal because you can still be in the home with your loved ones . . .

I would like to have some of my favorite songs played . . .I will have a list made ahead of time. I want a peaceful and joyful ceremony and I want my family and close friends to gather to support one another. At the end of the celebration, I want everyone to go to the Thirsty Whale for a beer and Spang’s for pizza!

When I die, I want to be cremated . . . I want it the way we do it in our culture. I want to have a three-day funeral and on the 4th day, it would be my burial/cremation day . . .I want everyone to wear white instead of black, which means they already let go of me. I also want to have a mass on my cremation day.

When I die, I would like to have a befitting burial ceremony as it is done in my Igbo customs. I chose this kind of funeral ceremony because that is what every average person wishes to have.

I want to be cremated . . . I want all attendees wearing their favorite color and I would like the song “Riders on the Storm” to be played . . .I truly hope all the attendees will appreciate the bass. At the end of this simple, short service, attendees will be given multi-colored helium-filled balloons . . . released to signify my release from this earth. . .They will be invited back to the house for ice cream cones, cheese popcorn, and a wide variety of other treats and much, much, much rock music . . .

I want to be cremated when I die. To me, it’s not just my culture to do so but it’s more peaceful to put my remains or ashes to the world. Let it free and not stuck in a casket.

These statements reflect a wide variety of conceptions and attitudes toward death. Culture plays a key role in the development of these conceptions and attitudes, and it also provides a framework within which they are expressed. However, it is important to note that culture does not provide set rules for how death is viewed and experienced, and there tends to be as much variation within cultures as well as between.

Think About It

What happens after death? This question has plagued humans since the beginning, and countless numbers of philosophies and religions attempt to explain the next life (if there is one). Some, like Buddhism, Jainism, Hinduism, and Sikhism, support the idea of reincarnation, or the idea that a living being starts a new life in a different physical body or form after each biological death. Some belief systems, such as those in the Abrahamic tradition (Christians, Jews, and Muslims), hold that the dead go to a specific plane of existence after death, as determined by God, or other divine judgment, based on their actions or beliefs during life.

Another important consideration related to conceptions and attitudes toward death involves social attitudes. Death, in many cases, can be the “elephant in the room,” a concept that remains ever-present but continues to be taboo for most individuals. Talking openly about death tends to be viewed negatively, or even as socially inappropriate. Specific social norms and standards regarding death vary between groups, but on a larger societal level, death is usually a topic reserved only for when it becomes absolutely necessary to bring it up.

Regardless of variations in conceptions and attitudes toward death, ceremonies provide survivors a sense of closure after a loss. These rites and ceremonies send the message that the death is real and allow friends and loved ones to express their love and duty to those who die. Under circumstances in which a person has been lost and presumed dead or when family members were unable to attend a funeral, there can continue to be a lack of closure that makes it difficult to grieve and to learn to live with loss. And although many people are still in shock when they attend funerals, the ceremony still provides a marker of the beginning of a new period of one’s life as a survivor.

The Body After Death

In most cultures, after the last offices have been performed and before the onset of significant decay, relations or friends arrange for ritual disposition of the body, either by destruction, or by preservation, or in a secondary use. In the U.S., this frequently means either cremation or interment in a tomb.

There are various methods of destroying human remains, depending on religious or spiritual beliefs, and upon practical necessity. Cremation is a very old and quite common custom. For some people, the act of cremation exemplifies the belief of the Christian concept of “ashes to ashes”. On the other hand, in India, cremation, and disposal of the bones in the sacred river, Ganges is common. Another method is sky burial, which involves placing the body of the deceased on high ground (a mountain) and leaving it for birds of prey to dispose of, as in Tibet. In some religious views, birds of prey are carriers of the soul to the heavens. Such practice may also have originated from pragmatic environmental issues, such as conditions in which the terrain (as in Tibet) is too stony or hard to dig, or in which there are few trees around to burn. As the local religion of Buddhism, in the case of Tibet, believes that the body after death is only an empty shell, there are more practical ways than the burial of disposing of a body, such as leaving it for animals to consume. In some fishing or marine communities, mourners may put the body into the water, in what is known as burial at sea. Several mountain villages have a tradition of hanging the coffin in the woods.

Since ancient times, in some cultures efforts have been made to slow, or largely stop the body’s decay processes before burial, as in mummification or embalming. This process may be done before, during, or after a funeral ceremony. The Toraja people of Indonesia are known to mummify their deceased loved ones and keep them in their homes for weeks, months, and sometimes even years, before holding a funeral service.

Developmental Perspectives on Death

Another key factor in individuals’ attitudes towards death and dying is where they are in their own lifespan development. First of all, individuals’ attitudes are linked to their cognitive ability to understand death and dying. Infants and toddlers cannot understand death. They function in the present and are aware of loss, separation, and disruptions in their routines. They are also attuned to the emotions and behaviors of significant adults in their lives, so a death of a loved one may cause a young child to become anxious and irritable, cry, or change their sleeping and eating habits.

A preschooler may approach death by asking when a deceased person is coming back and might search for them, thinking that death is temporary and reversible. They may experience brief but intense reactions, such as tantrums, or other behaviors like frightening dreams and disrupted sleep, bedwetting, clinging, and thumbsucking. Similarly, those in early childhood (age 4-7), might also ask where the deceased person is and search for them, as well as regress to younger behaviors. They might also think that the person’s death is their own fault, as per their belief in the power of their own thoughts and “magical thinking.” Their grief might be expressed through play, rather than verbally (Amsler, 2015).

Those in middle childhood (ages 7-10) begin to see death as final, not reversible, and universal. Developing Piaget’s concrete operational thinking, they may engage in personification, seeing death as a human figure who carried their loved one away. They may not really believe that death could happen to them or their family, maybe only to the very old or sick—they may also view death as a punishment. They might act out in school or they might try to keep a bond with the deceased by taking on that person’s role or behaviors.

Preadolescents (ages 10-12) try to understand both biological and emotional processes of death. But they try to hide their feelings and not seem different from their peers; they may seem indifferent or have outbursts. As Amsler (2015) noted, children’s and teens’ experiences with death and what adults tell them about death will also influence their comprehension. As teens develop formal operational thinking (ages 12-18), they can apply logic to abstractions; they spend more time pondering the meaning of life and death and what comes after death. Their understanding of death becomes more complex as they move from a binary logical concept (alive or dead) to a fuzzy logical concept with potential life after death, for instance. Adolescents are also tasked with integrating these beliefs into their own identity development.

What about attitudes toward death in adulthood? We’ve learned about adults becoming more concerned with their own mortality during middle adulthood, particularly as they experience the deaths of their own parents. Recently, Sinoff’s (2017) research on thanatophobia, or death anxiety, found differences in death anxiety between elderly patients and their adult children. Death anxiety may entail two parts—being anxious about death and the process of dying. The elderly were only anxious about the process of dying (i.e., suffering), but their adult children were very anxious about death itself, and mistakenly believed that their parents were also anxious about death itself. This is an important distinction and can significantly affect how medical information and end-of-life decisions are communicated within families (Sinoff, 2017). Consistent with this, if elders positively resolve Erikson’s final psychosocial crisis, ego integrity versus despair, they may not fear death but gain wisdom. If they are not feeling desperate (“despair” with time running out), then they may not be anxious or fearful about death.

Bereavement and Grief

Grief is the psychological, physical, and emotional experience and reaction to loss. People may experience grief in various ways, but several theories, such as Kübler-Ross’ stages of loss theory, attempt to explain and understand the way people deal with grief. Kübler-Ross’ famous theory, which we’ll examine in more detail soon, describes five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Grief reactions vary depending on whether a loss was anticipated or unexpected, (parents do not expect to lose their children, for example), and whether or not it occurred suddenly or after a long illness, and whether or not the survivor feels responsible for the death. Struggling with the question of responsibility is particularly felt by those who lose a loved one to suicide (Gibbons et al., 2018). These survivors may torment themselves with endless “what ifs” in order to make sense of the loss and reduce feelings of guilt. And family members may also hold one another responsible for the loss. The same may be true for any sudden or unexpected death, making conflict an added dimension to grief. Much of this laying of responsibility is an effort to think that we have some control over these losses; the assumption being that if we do not repeat the same mistakes, we can control what happens in our life. While grief describes the response to loss, bereavement describes the state of being following the death of someone.

As we’ve already learned in terms of attitudes toward death, individuals’ own lifespan developmental stage and cognitive level can influence their emotional and behavioral reactions to the death of someone they know. But what about the impact of the type of death or age of the deceased or relationship to the deceased upon bereavement?

Death of a child

Death of a child can take the form of a loss in infancy such as miscarriage or stillbirth or neonatal death, SIDS, or the death of an older child. In most cases, parents find the grief almost unbearably devastating, and it tends to hold greater risk factors than any other loss. This loss also bears a lifelong process: one does not get ‘over’ the death but instead must assimilate and live with it. Intervention and comforting support can make all the difference to the survival of a parent in this type of grief but the risk factors are great and may include family breakup or suicide. Feelings of guilt, whether legitimate or not, are pervasive, and the dependent nature of the relationship disposes parents to a variety of problems as they seek to cope with this great loss. Parents who suffer miscarriage or a regretful or coerced abortion may experience resentment towards others who experience successful pregnancies.

Suicide

Suicide rates are growing worldwide and over the last thirty years there has been international research trying to curb this phenomenon and gather knowledge about who is “at-risk”. When a parent loses their child through suicide it is traumatic, sudden, and affects all loved ones impacted by this child. Suicide leaves many unanswered questions and leaves most parents feeling hurt, angry, and deeply saddened by such a loss. Parents may feel they can’t openly discuss their grief and feel their emotions because of how their child died and how the people around them may perceive the situation. Parents, family members, and service providers have all confirmed the unique nature of suicide-related bereavement following the loss of a child. They report a wall of silence that goes up around them and how people interact with them. One of the best ways to grieve and move on from this type of loss is to find ways to keep that child as an active part of their lives. It might be privately at first but as parents move away from the silence they can move into a more proactive healing time.

Death of a spouse

The death of a spouse is usually a particularly powerful loss. A spouse often becomes part of the other in a unique way: many widows and widowers describe losing ‘half’ of themselves. The days, months, and years after the loss of a spouse will never be the same, and learning to live without them may be harder than one would expect. The grief experience is unique to each person. Sharing and building a life with another human being, then learning to live singularly, can be an adjustment that is more complex than a person could ever expect. Depression and loneliness are very common. Feeling bitter and resentful are normal feelings for the spouse who is “left behind”. Oftentimes, the widow/widower may feel it necessary to seek professional help in dealing with their new life.

After a long marriage, at older ages, the elderly may find it very difficult assimilation to begin anew; but at younger ages as well, a marriage relationship was often a profound one for the survivor.

Furthermore, most couples have a division of ‘tasks’ or ‘labor’, e.g., the husband mows the yard, the wife pays the bills, etc. which, in addition to dealing with great grief and life changes, means added responsibilities for the bereaved. Immediately after the death of a spouse, there are tasks that must be completed. Planning and financing a funeral can be very difficult if pre-planning was not completed. Changes in insurance, bank accounts, claiming life insurance, securing childcare are just some of the issues that can be intimidating to someone who is grieving. Social isolation may also become imminent, as many groups composed of couples find it difficult to adjust to the new identity of the bereaved, and the bereaved themselves have great challenges in reconnecting with others. Widows of many cultures, for instance, wear black for the rest of their lives to signify the loss of their spouse and their grief. Only in more recent decades has this tradition been reduced to shorter periods of time.

With increasing age, women were less likely to be married or divorced but more likely to be widowed, reflecting a longer life expectancy relative to men. About 2 out of 10 women aged 65 to 74 were widowed compared with 4 out of 10 women aged 75 to 84 and 7 out of 10 women 85 and older. More than twice as many women 85 and older were widowed (72 percent) compared to men of the same age (35 percent). The death of a spouse is one of life’s most disruptive experiences. It is especially hard for men who lose their wives. Often widowers do not have a network of friends or family members to fall back on and may have difficulty expressing their emotions to facilitate grief. Also, they may have been very dependent on their mates for routine tasks such as cooking, cleaning, etc.

Widows may have less difficulty because they do have a social network and can take care of their own daily needs. They may have more difficulty financially if their husbands have handled all the finances in the past. They are much less likely to remarry because many do not wish to and because there are fewer men available. At 65, there are 73 men to every 100 women. The sex ratio becomes even further imbalanced at 85 with 48 men to every 100 women (U. S. Census Bureau, 2011).

Death of a parent

For a child, the death of a parent, without support to manage the effects of the grief, may result in long-term psychological harm. This is more likely if the adult carers are struggling with their own grief and are psychologically unavailable to the child. There is a critical role of the surviving parent or caregiver in helping the children adapt to a parent’s death. Studies have shown that losing a parent at a young age did not just lead to negative outcomes; there are some positive effects. Some children had increased maturity, better coping skills, and improved communication. Adolescents valued other people more than those who have not experienced such a close loss (Ellis & Lloyd-Williams, 2008).

When an adult child loses a parent in later adulthood, it is considered to be “timely” and to be a normative life course event. This allows adult children to feel a permitted level of grief. However, research shows that the death of a parent in an adult’s midlife is not a normative event by any measure, but is a major life transition causing an evaluation of one’s own life or mortality. Others may shut out friends and family in processing the loss of someone with whom they have had the longest relationship (Marshall, 2004).

Death of a sibling

The loss of a sibling can be a devastating life event. Despite this, sibling grief is often the most disenfranchised or overlooked of the four main forms of grief, especially with regard to adult siblings. Grieving siblings are often referred to as the ‘forgotten mourners’ who are made to feel as if their grief is not as severe as their parents’ grief. However, the sibling relationship tends to be the longest significant relationship of the lifespan, and siblings who have been part of each other’s lives since birth, such as twins, help form and sustain each other’s identities; with the death of one sibling comes the loss of that part of the survivor’s identity because “your identity is based on having them there.”

The sibling relationship is a unique one, as they share a special bond and a common history from birth, have a certain role and place in the family, often complement each other, and share genetic traits. Siblings who enjoy a close relationship participate in each other’s daily lives and special events, confide in each other, share joys, spend leisure time together (whether they are children or adults), and have a relationship that not only exists in the present but often looks toward a future together (even into retirement). Surviving siblings lose this “companionship and a future” with their deceased siblings.

Loss during childhood

When a parent or caregiver dies or leaves, children may have symptoms of psychopathology, but they are less severe than in children with major depression. The loss of a parent, grandparent, or sibling can be very troubling in childhood, but even in childhood, there are age differences in relation to the loss. A very young child, under one or two, may be found to have no reaction if a carer dies, but other children may be affected by the loss.

At a time when trust and dependency are formed, a break of even of no more than separation can cause problems in well-being; this is especially true if the loss is around critical periods such as 8–12 months when attachment and separation are at their height information, and even a brief separation from a parent or other person who cares for the child can cause distress.

Even as a child grows older, death is still difficult to fathom and this affects how a child responds. For example, younger children see death more as a separation and may believe death is curable or temporary. Reactions can manifest themselves in “acting out” behaviors: a return to earlier behaviors such as sucking thumbs, clinging to a toy, or angry behavior; though they do not have the maturity to mourn as an adult, they feel the same intensity. As children enter pre-teen and teen years, there is a more mature understanding.

Children can experience grief as a result of losses due to causes other than death. For example, children who have been physically, psychologically, or sexually abused often grieve over the damage to or the loss of their ability to trust. Since such children usually have no support or acknowledgment from any source outside the family unit, this is likely to be experienced as disenfranchised grief.

Relocations can also cause children significant grief particularly if they are combined with other difficult circumstances such as neglectful or abusive parental behaviors, other significant losses, etc.

Loss of a friend or classmate

Children may experience the death of a friend or a classmate through illness, accidents, suicide, or violence. Initial support involves reassuring children that their emotional and physical feelings are normal. Schools are advised to plan for these possibilities in advance.

Survivor guilt (or survivor’s guilt; also called survivor syndrome or survivor’s syndrome) is a mental condition that occurs when a person perceives themselves to have done wrong by surviving a traumatic event when others did not. It may be found among survivors of combat, natural disasters, epidemics, among the friends and family of those who have died by suicide, and in non-mortal situations such as among those whose colleagues are laid off.

Anticipatory grief occurs when a death is expected and survivors have time to prepare to some extent before the loss. Anticipatory grief can include the same denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance experienced in loss one might experience after a death; this can make the adjustment after a loss somewhat easier, although a person may then go through the stages of loss again after the death. A death after a long-term, painful illness may bring family members a sense of relief that the suffering is over or the exhausting process of caring for someone who is ill is over.

Complicated grief involves a distinct set of maladaptive or self-defeating thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that occur as a negative response to a loss. From a cognitive and emotional perspective, these individuals tend to experience extreme bitterness over the loss, intense preoccupation with the deceased, and a need to feel connected to the deceased. These feelings often lead the grieving individual to engage in problematic behaviors that further prevent positive coping and delay the return to normalcy. He or she may spend excessive amounts of time visiting the deceased person’s grave, talking to the deceased person, or trying to connect with the deceased person on a spiritual level, often forgoing other responsibilities or tasks to do so. The extreme nature of these thoughts, emotions, and behaviors separate this type of grief from the normal grieving process.

Disenfranchised grief may be experienced by those who have to hide the circumstances of their loss or whose grief goes unrecognized by others. Loss of an ex-spouse, lover, or pet may be examples of disenfranchised grief.

It has been said that intense grief lasts about two years or less, but grief is felt throughout life. One loss triggers the feelings that surround another. People grieve with varied intensity throughout the remainder of their lives. It does not end. But it eventually becomes something that a person has learned to live with. As long as we experience loss, we experience grief.

There are layers of grief. Initial denial, marked by shock and disbelief in the weeks following a loss may become an expectation that the loved one will walk in the door. And anger directed toward those who could not save our loved one’s life may become angry that life did not turn out as we expected. There is no right way to grieve. A bereavement counselor expressed it well by saying that grief touches us on the shoulder from time to time throughout life.

Grief and mixed emotions go hand in hand. A sense of relief is accompanied by regrets and periods of reminiscing about our loved ones are interspersed with feeling haunted by them in death. Our outward expressions of loss are also sometimes contradictory. We want to move on but at the same time are saddened by going through a loved one’s possessions and giving them away. We may no longer feel sexual arousal or we may want sex to feel connected and alive. We need others to befriend us but may get angry at their attempts to console us. These contradictions are normal and we need to allow ourselves and others to grieve in their own time and in their own ways.

The “death-denying, grief-dismissing world” is often the approach to grief in our modern world. We are asked to grieve privately, quickly, and to medicate our suffering. Employers grant us 3 to 5 days for bereavement if our loss is that of an immediate family member. And such leaves are sometimes limited to no more than once per year. Yet grief takes much longer and the bereaved are seldom ready to perform well on the job. It becomes a clash between life having to continue, and the individual being ready for it to do so. One coping mechanism that can help smooth out this conflict is called the fading affect bias. Based on a collection of similar findings, the fading affect bias suggests that negative events, such as the death of a loved one, tend to lose their emotional intensity at a faster rate than pleasant events. This is believed to help enhance pleasant experiences and avoid the negative emotions associated with unpleasant ones, thus helping the individual return to his or her normal daily routines following a loss.

Stages of Loss

The complex construct of death is associated with a variety of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, that vary between individuals and groups. To some, death is the final end, when the body ceases to function, with nothing occurring next. To others, death is the start of a new journey and is its own beginning. These varying viewpoints are shaped by numerous factors related to culture, religion, social norms, personal experiences, and more. It is no surprise then that multiple theories have been created to understand the occurrence of death on cognitive, emotional, and behavioral levels; each offering different explanations for what individuals go through during death.

Kübler-Ross’ Stages of Loss

Kübler-Ross (1965) described five stages of loss experienced by someone who faces the news of their impending death (based on her work and interviews with terminally ill patients). These “stages” are not really stages that a person goes through in order or only once; nor are they stages that occur with the same intensity. Indeed, the process of death is influenced by a person’s life experiences, the timing of their death in relation to life events, the predictability of their death based on health or illness, their belief system, and their assessment of the quality of their own life. Nevertheless, these stages provide a framework to help us to understand and recognize some of what a dying person experiences psychologically. And by understanding, we are more equipped to support that person as they die.

Denial is often the first reaction to overwhelming, unimaginable news. Denial, or disbelief or shock, protects us by allowing such news to enter slowly and to give us time to come to grips with what is taking place. The person who receives positive test results for life-threatening conditions may question the results, seek second opinions, or may simply feel a sense of disbelief psychologically even though they know that the results are true.

Anger also provides us with protection in that being angry energizes us to fight against something and gives structure to a situation that may be thrusting us into the unknown. It is much easier to be angry than to be sad or in pain or depressed. It helps us to temporarily believe that we have a sense of control over our future and to feel that we have at least expressed our rage about how unfair life can be. Anger can be focused on a person, a health care provider, at God, or at the world in general. And it can be expressed over issues that have nothing to do with our death; consequently, being in this stage of loss is not always obvious.

Bargaining involves trying to think of what could be done to turn the situation around. Living better, devoting self to a cause, being a better friend, parent, or spouse, are all agreements one might willingly commit to if doing so would lengthen life. Asking to just live long enough to witness a family event or finish a task are examples of bargaining.

Depression is sadness and sadness is appropriate for such an event. Feeling the full weight of loss, crying, and losing interest in the outside world is an important part of the process of dying. This depression makes others feel very uncomfortable and family members may try to console their loved one. Sometimes hospice care may include the use of antidepressants to reduce depression during this stage.

Acceptance involves learning how to carry on and to incorporate this aspect of the life span into daily existence. Reaching acceptance does not in any way imply that people who are dying are happy about it or content with it. It means that they are facing it and continuing to make arrangements and to say what they wish to say to others. Some terminally ill people find that they live life more fully than ever before after they come to this stage.

In some ways, these five stages serve as cognitive defense mechanisms, allowing the individual to make sense of the situation while coming to terms with what is happening. They are, in other words, the mind’s way of gradually recognizing the implications of one’s impending death and giving him or her the chance to process it. These stages provide a type of framework in which dying is experienced, although it is not exactly the same for every individual in every case.

Since Kübler-Ross presented these stages of loss, several other models have been developed. These subsequent models, in many ways, build on that of Kübler-Ross, offering expanded views of how individuals process loss and grief. While Kübler-Ross’ model was restricted to dying individuals, subsequent theories tended to focus on loss as a more general construct. This ultimately suggests that facing one’s own death is just one example of the grief and loss that human beings can experience, and that other loss or grief-related situations tend to be processed in a similar way.

Other Models on Grief

One such model was presented by Worden (1991), which explained the process of grief through a set of four different tasks that the individual must complete in order to resolve the grief. These tasks include: (a) accepting that the loss has occurred, (b) working through and experiencing the pain associated with grief, (c) adjusting the changes that the loss created in the environment, and (d) moving past the loss on an emotional level.

Another model is that of Parkes (1998), which broke down grief into four stages, including: (a) shock, (b) yearning, (c) despair, and (d) recovery. Although comprised of somewhat different stages than those of Kübler-Ross’ model, Parkes’ stages still reflected an ongoing process that the individual goes through, each of which was characterized by different thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Throughout this process, the individual gradually moves closer to accepting the situation and being able to continue with his or her daily life to the greatest extent possible.

A different approach was proposed by Strobe and Shut (1999), which suggested that individuals cope with grief through an ongoing set of processes related to both loss and restoration. The loss-oriented processes included: (a) grief work, (b) intrusion on grief, (c) denying or avoiding changes toward restoration, and (d) the breaking of bonds or ties. The restoration-oriented processes included: (a) attending to life changes, (b) distracting oneself from grief, (c) doing new things, and (d) establishing new roles, identities, and relationships. Since each individual experiences grief and loss differently, in light of personal, cultural, and environmental factors, these processes often occur simultaneously, and not in a set order.

We no longer think that there is a “right way” to experience grief and loss. People move through a variety of stages with different frequencies and in different ways. The theories that have been developed to help explain and understand this complex process have shifted over time to encompass a wider variety of situations, as well as to present implications for helping and supporting the individual(s) who are going through it. The following strategies have been identified as effective in the support of healthy grieving (American Psychological Association, 2019).

- Talk about the death. This will help the surviving individuals understand what happened and remember the deceased in a positive way. When coping with death, it can be easy to get wrapped up in denial, which can lead to isolation and lack of a solid support system.

- Accept the multitude of feelings. The death of a loved one can, and almost always does, trigger numerous emotions. It is normal for sadness, frustration, and in some cases exhaustion to be experienced.

- Take care of yourself and your family. Remembering to keep one’s own health and the health of their family a priority can help with moving through each day effectively. Making a conscious effort to eat well, exercise regularly, and obtain adequate rest is important.

- Reach out and help others dealing with the loss. It has long been recognized that helping others can enhance one’s own mood and general mental state. Helping others as they cope with the loss can have this effect, as can sharing stories of the deceased.

- Remember and celebrate the lives of your loved ones. This can be a great way to honor the relationship that was once had with the deceased. Possibilities can include donating to a charity that the deceased supported, framing photos of fun experiences with the deceased, planting a tree or garden in memory of the deceased, or anything else that feels right for the particular situation.

Additional Supplemental Resources

Websites

- National Alliance for Grieving Children

- The NAGC is a nationwide network comprised of professionals, institutions, and volunteers who promote best practices, educational programming, and critical resources to facilitate the mental, emotional and physical health of grieving children and their families.

Videos

-

-

Brené Brown on Empathy

- What is the best way to ease someone’s pain and suffering? In this beautifully animated RSA Short, Dr. Brené Brown reminds us that we can only create a genuine empathic connection if we are brave enough to really get in touch with our own fragilities.

-

-

We don’t “move on” from grief. We move forward with it | Nora McInerny

- In a talk that’s by turns heartbreaking and hilarious, writer and podcaster Nora McInerny shares her hard-earned wisdom about life and death. Her candid approach to something that will, let’s face it, affect us all, is as liberating as it is gut-wrenching. Most powerfully, she encourages us to shift how we approach grief. “A grieving person is going to laugh again and smile again,” she says. “They’re going to move forward. But that doesn’t mean that they’ve moved on.

- The Brittany Maynard Story

- In October 2014, 29-year-old Brittany Maynard told the world she planned to die gently with dignity before brain cancer completely destroyed her body and mind.

-

The Science of Aging

- Why do we age, from a biological perspective?

-

Being Mortal (full film) | FRONTLINE

- How do you talk about death with a dying loved one? Dr. Atul Gawande explores death, dying, and why even doctors struggle to discuss being mortal with patients, in this Emmy-nominated documentary.