Emerging Adulthood

Why learn about development changes during emerging adulthood?

Emerging adulthood has been proposed as a new life stage between adolescence and young adulthood, lasting roughly from ages 18 to 25. Five features make emerging adulthood distinctive: identity explorations, instability, self-focus, feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood, and a sense of broad possibilities for the future. Emerging adulthood is found mainly in industrialized countries, where most young people obtain tertiary education and median ages of entering marriage and parenthood are around 30. There are variations in emerging adulthood within industrialized countries. It lasts longest in Europe, and in Asian industrialized countries, the self-focused freedom of emerging adulthood is balanced by obligations to parents and by conservative views of sexuality. In non-industrialized countries, although today emerging adulthood exists only among the middle-class elite, it can be expected to grow in the 21st century as these countries become more affluent.

Learning Objectives

- Explain where, when, and why a new life stage of emerging adulthood appeared over the past half-century.

- Identify the five features that distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages.

- Describe the variations in emerging adulthood in countries around the world.

What you’ll learn to do: explain developmental tasks during emerging adulthood

Think for a moment about the lives of your grandparents and great-grandparents when they were in their twenties. How do their lives at that age compare to your life? If they were like most other people of their time, their lives were quite different than yours. What happened to change the twenties so much between their time and our own? And how should we understand the 18–25 age period today?

The theory of emerging adulthood proposes that a new life stage has arisen between adolescence and young adulthood over the past half-century in industrialized countries. Fifty years ago, most young people in these countries had entered stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. Relatively few people pursued education or training beyond secondary school, and, consequently, most young men were full-time workers by the end of their teens. Relatively few women worked in occupations outside the home, and the median marriage age for women in the United States and in most other industrialized countries in 1960 was around 20 (Arnett & Taber, 1994; Douglass, 2005). The median marriage age for men was around 22, and married couples usually had their first child about one year after their wedding day. All told, for most young people half a century ago, their teenage adolescence led quickly and directly to stable adult roles in love and work by their late teens or early twenties. These roles would form the structure of their adult lives for decades to come.

Now, all that has changed. A higher proportion of young people than ever before—about 70% in the United States—pursue education and training beyond secondary school (National Center for Education Statistics, 2012). The early twenties are not a time of entering stable adult work but a time of immense job instability: In the United States, the average number of job changes from ages 20 to 29 is seven. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is now 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). Consequently, a new stage of the life span, emerging adulthood, has been created, lasting from the late teens through the mid-twenties, roughly ages 18 to 25.

The Five Features of Emerging Adulthood

Five characteristics distinguish emerging adulthood from other life stages (Arnett, 2004). Emerging adulthood is:

- the age of identity explorations;

- the age of instability;

- the self-focused age;

- the age of feeling in-between; and

- the age of possibilities.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of emerging adulthood is that it is the age of identity explorations. That is, it is an age when people explore various possibilities in love and work as they move toward making enduring choices. Through trying out these different possibilities, they develop a more definite identity, including an understanding of who they are, what their capabilities and limitations are, what their beliefs and values are, and how they fit into the society around them. Erik Erikson (1950), who was the first to develop the idea of identity, proposed that it is mainly an issue in adolescence; but that was more than 50 years ago, and today it is mainly in emerging adulthood that identity explorations take place (Côté, 2006).

The explorations of emerging adulthood also make it the age of instability. As emerging adults explore different possibilities in love and work, their lives are often unstable. A good illustration of this instability is their frequent moves from one residence to another. Rates of residential change in American society are much higher at ages 18 to 29 than at any other period of life (Arnett, 2004). This reflects the explorations going on in emerging adults’ lives. Some move out of their parents’ household for the first time in their late teens to attend a residential college, whereas others move out simply to be independent (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). They may move again when they drop out of college or when they graduate. They may move to cohabit with a romantic partner and then move out when the relationship ends. Some move to another part of the country or the world to study or work. For nearly half of American emerging adults, residential change includes moving back in with their parents at least once (Goldscheider & Goldscheider, 1999). In some countries, such as in southern Europe, emerging adults remain in their parents’ home rather than move out; nevertheless, they may still experience instability in education, work, and love relationships (Douglass, 2005, 2007).

Emerging adulthood is also a self-focused age. Most American emerging adults move out of their parents’ home at age 18 or 19 and do not marry or have their first child until at least their late twenties (Arnett, 2004). Even in countries where emerging adults remain in their parents’ home through their early twenties, as in southern Europe and in Asian countries such as Japan, they establish a more independent lifestyle than they had as adolescents (Rosenberger, 2007). Emerging adulthood is a time between adolescents’ reliance on parents and adults’ long-term commitments in love and work, and during these years, emerging adults focus on themselves as they develop the knowledge, skills, and self-understanding they will need for adult life. In the course of emerging adulthood, they learn to make independent decisions about everything from what to have for dinner to whether or not to get married.

Another distinctive feature of emerging adulthood is that it is an age of feeling in-between, not adolescent but not fully adult, either. When asked, “Do you feel that you have reached adulthood?” the majority of emerging adults respond neither yes nor no but with the ambiguous “in some ways yes, in some ways no” (Arnett, 2003, 2012). It is only when people reach their late twenties and early thirties that a clear majority feels adult. Most emerging adults have the subjective feeling of being in a transitional period of life, on the way to adulthood but not there yet. This “in-between” feeling in emerging adulthood has been found in a wide range of countries, including Argentina (Facio & Micocci, 2003), Austria (Sirsch, Dreher, Mayr, & Willinger, 2009), Israel (Mayseless & Scharf, 2003), the Czech Republic (Macek, Bejček, & Vaníčková, 2007), and China (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

Finally, emerging adulthood is the age of possibilities, when many different futures remain possible, and when little about a person’s direction in life has been decided for certain. It tends to be an age of high hopes and great expectations, in part because few of their dreams have been tested in the fires of real life. In one national survey of 18- to 24-year-olds in the United States, nearly all—89%—agreed with the statement, “I am confident that one day I will get to where I want to be in life” (Arnett & Schwab, 2012). This optimism in emerging adulthood has been found in other countries as well (Nelson & Chen, 2007).

International Variations

The five features proposed in the theory of emerging adulthood originally were based on research involving about 300 Americans between ages 18 and 29 from various ethnic groups, social classes, and geographical regions (Arnett, 2004). To what extent does the theory of emerging adulthood apply internationally?

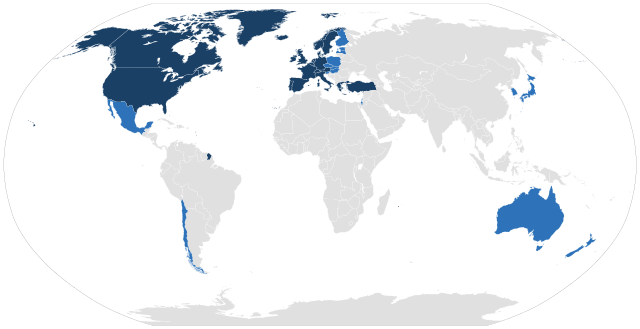

The answer to this question depends greatly on what part of the world is considered. Demographers make a useful distinction between the non-industrialized countries that comprise the majority of the world’s population and the industrialized countries that are part of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), including the United States, Canada, western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The current population of OECD countries (also called industrialized countries) is 1.2 billion, about 18% of the total world population (UNDP, 2011). The rest of the human population resides in non-industrialized countries, which have much lower median incomes; much lower median educational attainment; and much higher incidence of illness, disease, and early death. Let us consider emerging adulthood in OECD countries first, then in non-industrialized countries.

EA in OECD Countries: The Advantages of Affluence

The same demographic changes as described above for the United States have taken place in other OECD countries as well. This is true of participation in postsecondary education as well as median ages for entering marriage and parenthood (UN data, 2010). However, there is also substantial variability in how emerging adulthood is experienced across OECD countries. Europe is the region where emerging adulthood is the longest and most leisurely. The median ages for entering marriage and parenthood are near 30 in most European countries (Douglass, 2007). Europe today is the location of the most affluent, generous, and egalitarian societies in the world—in fact, in human history (Arnett, 2007). Governments pay for tertiary education, assist young people in finding jobs, and provide generous unemployment benefits for those who cannot find work. In northern Europe, many governments also provide housing support. Emerging adults in European societies make the most of these advantages, gradually making their way to adulthood during their twenties while enjoying travel and leisure with friends.

The lives of Asian emerging adults in industrialized countries such as Japan and South Korea are in some ways similar to the lives of emerging adults in Europe and in some ways strikingly different. Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults tend to enter marriage and parenthood around age 30 (Arnett, 2011). Like European emerging adults, Asian emerging adults in Japan and South Korea enjoy the benefits of living in affluent societies with generous social welfare systems that provide support for them in making the transition to adulthood—for example, free university education and substantial unemployment benefits.

However, in other ways, the experience of emerging adulthood in Asian OECD countries is markedly different than in Europe. Europe has a long history of individualism, and today’s emerging adults carry that legacy with them in their focus on self-development and leisure during emerging adulthood. In contrast, Asian cultures have a shared cultural history emphasizing collectivism and family obligations. Although Asian cultures have become more individualistic in recent decades as a consequence of globalization, the legacy of collectivism persists in the lives of emerging adults. They pursue identity explorations and self-development during emerging adulthood, like their American and European counterparts, but within narrower boundaries set by their sense of obligations to others, especially their parents (Phinney & Baldelomar, 2011). For example, in their views of the most important criteria for becoming an adult, emerging adults in the United States and Europe consistently rank financial independence among the most important markers of adulthood. In contrast, emerging adults with an Asian cultural background especially emphasize becoming capable of supporting parents financially as among the most important criteria (Arnett, 2003; Nelson, Badger, & Wu, 2004). This sense of family obligation may curtail their identity explorations in emerging adulthood to some extent, as they pay more heed to their parents’ wishes about what they should study, what job they should take, and where they should live than emerging adults do in the West (Rosenberger, 2007).

Another notable contrast between Western and Asian emerging adults is in their sexuality. In the West, premarital sex is normative by the late teens, more than a decade before most people enter marriage. In the United States and Canada, and in northern and eastern Europe, cohabitation is also normative; most people have at least one cohabiting partnership before marriage. In southern Europe, cohabiting is still taboo, but premarital sex is tolerated in emerging adulthood. In contrast, both premarital sex and cohabitation remain rare and forbidden throughout Asia. Even dating is discouraged until the late twenties when it would be a prelude to a serious relationship leading to marriage. In cross-cultural comparisons, about three-fourths of emerging adults in the United States and Europe report having had premarital sexual relations by age 20, versus less than one fifth in Japan and South Korea (Hatfield & Rapson, 2006).

EA in Non-Industrialized Countries: Low But Rising

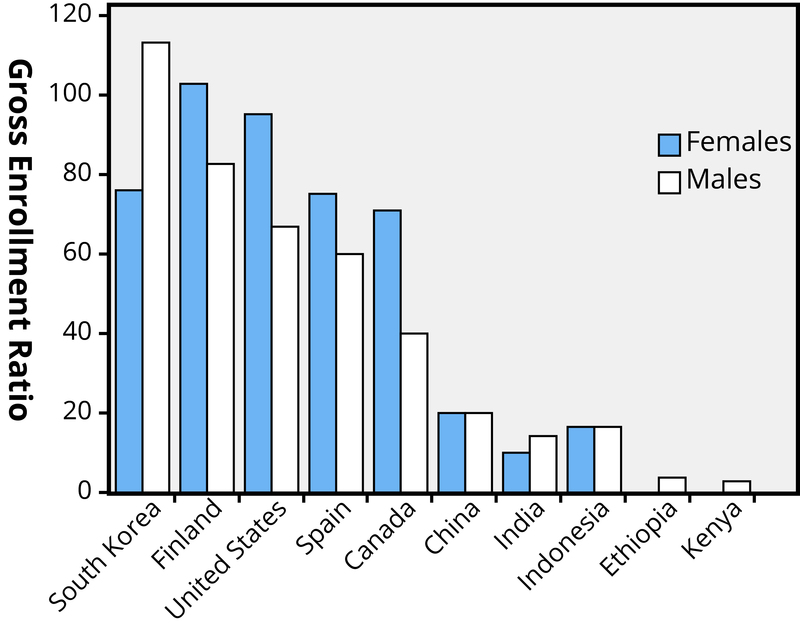

Emerging adulthood is well established as a normative life stage in the industrialized countries described thus far, but it is still growing in non-industrialized countries. Demographically, in non-industrialized countries as in OECD countries, the median ages for entering marriage and parenthood have been rising in recent decades, and an increasing proportion of young people have obtained post-secondary education. Nevertheless, currently, it is only a minority of young people in non-industrialized countries who experience anything resembling emerging adulthood. The majority of the population still marries around age 20 and has long finished education by the late teens. As you can see in Figure 1, rates of enrollment in tertiary education are much lower in non-industrialized countries (represented by the five countries on the right) than in OECD countries (represented by the five countries on the left).

For young people in non-industrialized countries, emerging adulthood exists only for the wealthier segment of society, mainly the urban middle class, whereas the rural and urban poor—the majority of the population—have no emerging adulthood and may even have no adolescence because they enter adult-like work at an early age and also begin marriage and parenthood relatively early. What Saraswathi and Larson (2002) observed about adolescence applies to emerging adulthood as well: “In many ways, the lives of middle-class youth in India, South East Asia, and Europe have more in common with each other than they do with those of poor youth in their own countries.” However, as globalization proceeds, and economic development along with it, the proportion of young people who experience emerging adulthood will increase as the middle class expands. By the end of the 21st century, emerging adulthood is likely to be normative worldwide.

Education and Work

Education in Early Adulthood

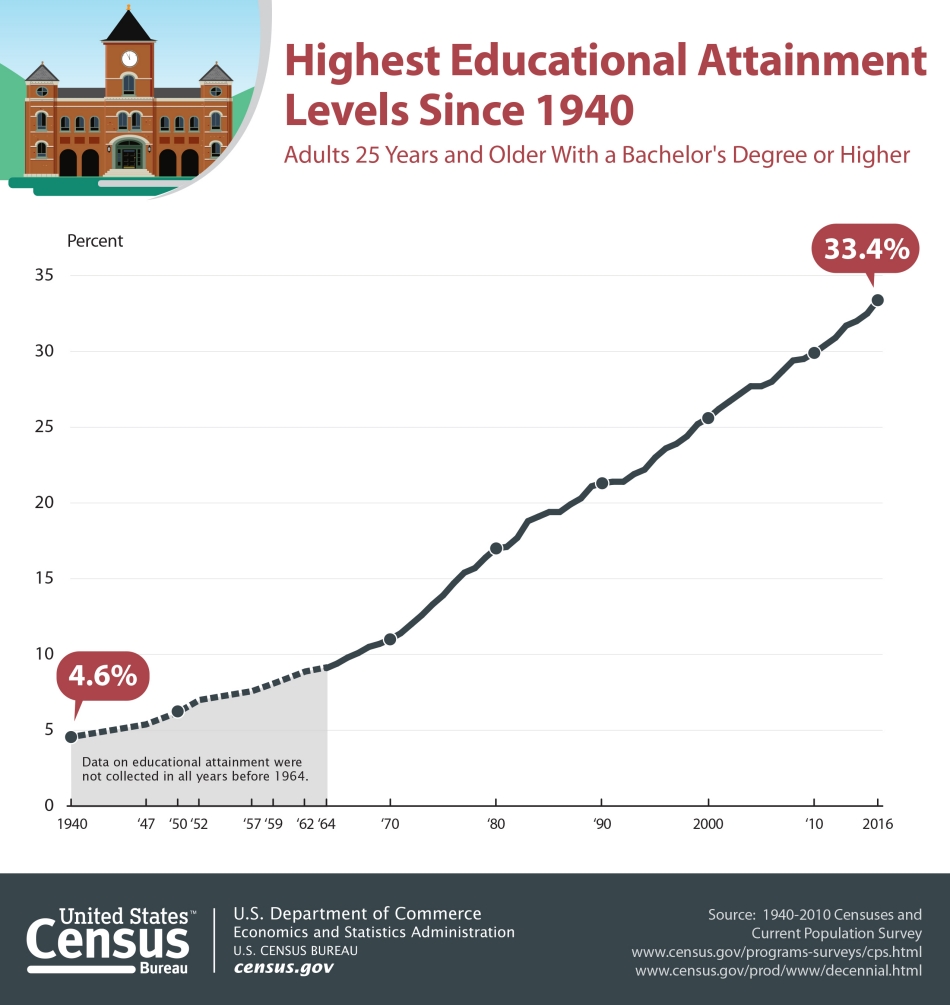

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2017), 90 percent of the American population 25 and older have completed high school or higher level of education—compare this to just 24 percent in 1940! Each generation tends to earn (and perhaps need) increased levels of formal education. As we can see in the graph, approximately one-third of the American adult population has a bachelor’s degree or higher, as compared with less than 5 percent in 1940. Educational attainment rates vary by gender and race. In all races combined, women are slightly more likely to have graduated from college than men; that gap widens with graduate and professional degrees. However, wide racial disparities still exist. For example, 23 percent of African-Americans have a college degree and only 16.4 percent of Hispanic Americans have a college degree, compared to 37 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans. The college graduation rates of African-Americans and Hispanic Americans have been growing in recent years, however (the rate has doubled since 1991 for African-Americans and it has increased 60 percent in the last two decades for Hispanic-Americans).

Education and the Workplace

With the rising costs of higher education, various news headlines have asked if a college education is worth the cost. One way to address this question is in terms of the earning potential associated with various levels of educational achievement. In 2016, the average earnings for Americans 25 and older with only a high school education was $35,615, compared with $65,482 for those with a bachelor’s degree, compared with $92,525 for those with more advanced degrees. Average earnings vary by gender, race, and geographical location in the United States.

Of concern in recent years is the relationship between higher education and the workplace. In 2005, American educator and then Harvard University President, Derek Bok, called for a closer alignment between the goals of educators and the demands of the economy. Companies outsource much of their work, not only to save costs but to find workers with the skills they need. What is required to do well in today’s economy? Colleges and universities, he argued, need to promote global awareness, critical thinking skills, the ability to communicate, moral reasoning, and responsibility in their students. Regional accrediting agencies and state organizations provide similar guidelines for educators. Workers need skills in listening, reading, writing, speaking, global awareness, critical thinking, civility, and computer literacy—all skills that enhance success in the workplace.

More than a decade later, the question remains: does formal education prepare young adults for the workplace? It depends on whom you ask. In an article referring to information from the National Association of Colleges and Employers’ 2018 Job Outlook Survey, Bauer-Wolf (2018) explains that employers perceive gaps in students’ competencies but many graduating college seniors are overly confident. The biggest difference was in perceived professionalism and work ethic (only 43 percent of employers thought that students are competent in this area compared to 90 percent of the students). Similar differences were also found in terms of oral communication, written communication, and critical thinking skills. Only in terms of digital technology skills were more employers confident about students’ competencies than were the students (66 percent compared to 60 percent).

It appears that students need to learn what some call “soft skills,” as well as the particular knowledge and skills within their college major. As education researcher Loni Bordoloi Pazich (2018) noted, most American college students today are enrolling in business or other pre-professional programs and to be effective and successful workers and leaders, they would benefit from the communication, teamwork, and critical thinking skills, as well as the content knowledge, gained from liberal arts education. In fact, two-thirds of children starting primary school now will be employed in jobs in the future that currently do not exist. Therefore, students cannot learn every single skill or fact that they may need to know, but they can learn how to learn, think, research, and communicate well so that they are prepared to continually learn new things and adapt effectively in their careers and lives since the economy, technology, and global markets will continue to evolve.

An important consideration in managing employees is age. Workers’ expectations and attitudes are developed in part by experience in particular cultural time periods. Generational constructs are somewhat arbitrary, yet they may be helpful in setting broad directions to organizational management as one generation leaves the workforce and another enters it. The baby boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964) is in the process of leaving the workforce and will continue to depart it for a decade or more. Generation X (born between the early 1960s and the 1980s) are now in the middle of their careers. Millennials (born from 1979 to early 1994) began to come of age at the turn of the century, and are early in their careers.

Today, as these three different generations work side by side in the workplace, employers and managers need to be able to identify their unique characteristics. Each generation has distinctive expectations, habits, attitudes, and motivations (Elmore, 2010). One of the major differences among these generations is knowledge of the use of technology in the workplace. Millennials are technologically sophisticated and believe their use of technology sets them apart from other generations. They have also been characterized as self-centered and overly self-confident. Their attitudinal differences have raised concerns for managers about maintaining their motivation as employees and their ability to integrate into organizational culture created by baby boomers (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010). For example, millennials may expect to hear that they need to pay their dues in their jobs from baby boomers who believe they paid their dues in their time. Yet millennials may resist doing so because they value life outside of work to a greater degree (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010). Meister & Willyerd (2010) suggest alternative approaches to training and mentoring that will engage millennials and adapt to their need for feedback from supervisors: reverse mentoring, in which a younger employee educates a senior employee in social media or other digital resources. The senior employee then has the opportunity to provide useful guidance within a less demanding role.

Recruiting and retaining millennials and Generation X employees poses challenges that did not exist in previous generations. The concept of building a career with the company is not relatable to most Generation X employees, who do not expect to stay with one employer for their career. This expectation arises from a reduced sense of loyalty because they do not expect their employer to be loyal to them (Gibson, Greenwood, & Murphy, 2009). Retaining Generation X workers thus relies on motivating them by making their work meaningful (Gibson, Greenwood, & Murphy, 2009). Since millennials lack an inherent loyalty to the company, retaining them also requires effort in the form of nurturing through frequent rewards, praise, and feedback.

Millennials are also interested in having many choices, including options in work scheduling, choice of job duties, and so on. They also expect more training and education from their employers. Companies that offer the best benefits package and brand attract millennials (Myers & Sadaghiani, 2010).

Career Choices in Early Adulthood

Hopefully, we are each becoming lifelong learners, particularly since we are living longer and will most likely change jobs multiple times during our lives. However, for many, our job changes will be within the same general occupational field, so our initial career choice is still significant. We’ve seen with Erikson that identity largely involves occupation and, as we will learn in the next section, Levinson found that young adults typically form a dream about work (though females may have to choose to focus relatively more on work or family initially with “split” dreams). The American School Counselor Association recommends that school counselors aid students in their career development beginning as early as kindergarten and continue this development throughout their education.

One of the most well-known theories about career choice is from John Holland (1985), who proposed that there are six personality types (realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional), as well as varying types of work environments. The better matched one’s personality is to the workplace characteristics, the more satisfied and successful one is predicted to be with that career or vocational choice. Research support has been mixed and we should note that there is more to satisfaction and success in a career than one’s personality traits or likes and dislikes. For instance, education, training, and abilities need to match the expectations and demands of the job, plus the state of the economy, availability of positions, and salary rates may play practical roles in choices about work.

Link to Learning: What’s Your Right Career?

To complete a free online career questionnaire and identify potential careers based on your preferences, go to Career One Stop Questionnaire

Did you find out anything interesting? Think of this activity as a starting point to your career exploration. Other great ways for young adults to research careers include informational interviewing, job shadowing, volunteering, practicums, and internships. Once you have a few careers in mind that you want to find out more about, go to the Occupational Outlook Handbook from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to learn about job tasks, required education, average pay, and projected outlook for the future.

The O*Net database describes the skills, knowledge, and education required for occupations, as well as what personality types and work styles are best suited to the role. See what it has to say about being a food server in a restaurant or an elementary school teacher or an industrial-organizational psychologist to learn more about these career paths.

EVERYDAY CONNECTION: Preparing for the Job Interview

You might be wondering if psychology research can tell you how to succeed in a job interview. As you can imagine, most research is concerned with the employer’s interest in choosing the most appropriate candidate for the job, a goal that makes sense for the candidate too. But suppose you are not the only qualified candidate for the job; is there a way to increase your chances of being hired? A limited amount of research has addressed this question.

As you might expect, nonverbal cues are important in an interview. Liden, Martin, & Parsons (1993) found that lack of eye contact and smiling on the part of the applicant led to lower applicant ratings. Studies of impression management on the part of an applicant have shown that self-promotion behaviors generally have a positive impact on interviewers (Gilmore & Ferris, 1989). Different personality types use different forms of impression management, for example, extroverts use verbal self-promotion, and applicants high in agreeableness use non-verbal methods such as smiling and eye contact. Self-promotion was most consistently related with a positive outcome for the interview, particularly if it was related to the candidate’s person-job fit. However, it is possible to overdo self-promotion with experienced interviewers (Howard & Ferris, 1996). Barrick, Swider & Stewart (2010) examined the effect of first impressions during the rapport-building that typically occurs before an interview begins. They found that initial judgments by interviewers during this period were related to job offers and that the judgments were about the candidate’s competence and not just likability. Levine and Feldman (2002) looked at the influence of several nonverbal behaviors in mock interviews on candidates’ likability and projections of competence. Likability was affected positively by greater smiling behavior. Interestingly, other behaviors affected likability differently depending on the gender of the applicant. Men who displayed higher eye contact were less likable; women were more likable when they made greater eye contact. However, for this study male applicants were interviewed by men and female applicants were interviewed by women. In a study carried out in a real setting, DeGroot & Gooty (2009) found that nonverbal cues affected interviewers’ assessments about candidates. They looked at visual cues, which can often be modified by the candidate, and vocal (nonverbal) cues, which are more difficult to modify. They found that interviewer judgment was positively affected by visual and vocal cues of conscientiousness, visual and vocal cues of openness to experience, and vocal cues of extroversion.

What is the take-home message from the limited research that has been done? Learn to be aware of your behavior during an interview. You can do this by practicing and soliciting feedback from mock interviews. Pay attention to any nonverbal cues you are projecting and work at presenting nonverbal cures that project confidence and positive personality traits. And finally, pay attention to the first impression you are making as it may also have an impact on the interview.

What you’ll learn to do: explain theories and perspectives on psychosocial development in emerging adulthood

From a lifespan developmental perspective, growth and development do not stop in childhood or adolescence; they continue throughout adulthood. In this section, we will build on Erikson’s psychosocial stages, then be introduced to theories about transitions that occur during adulthood. According to Levinson, we alternate between periods of change and periods of stability. More recently, Arnett notes that transitions to adulthood happen at later ages than in the past and he proposes that there is a new stage between adolescence and early adulthood called, “emerging adulthood.” Let’s see what you think.

learning outcomes

- Describe Erikson’s stage of intimacy vs. isolation

- Describe personality in emerging adulthood

Theories of Early Adult Psychosocial Development

Erikson’s Theory

| Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Age (years) | Developmental Task | Description |

| 1 | 0–1 | Trust vs. mistrust | Trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met |

| 2 | 1–3 | Autonomy vs. shame/doubt | Develop a sense of independence in many tasks |

| 3 | 3–6 | Initiative vs. guilt | Take initiative on some activities—may develop guilt when unsuccessful or boundaries overstepped |

| 4 | 7–11 | Industry vs. inferiority | Develop self-confidence in abilities when competent or sense of inferiority when not |

| 5 | 12–18 | Identity vs. confusion | Experiment with and develop identity and roles |

| 6 | 19–29 | Intimacy vs. isolation | Establish intimacy and relationships with others |

| 7 | 30–64 | Generativity vs. stagnation | Contribute to society and be part of a family |

| 8 | 65– | Integrity vs. despair | Assess and make sense of life and meaning of contributions |

Intimacy vs. Isolation (Love)

Erikson (1950) believed that the main task of early adulthood is to establish intimate relationships and not feel isolated from others. Intimacy does not necessarily involve romance; it involves caring about another and sharing one’s self without losing one’s self. This developmental crisis of “intimacy versus isolation” is affected by how the adolescent crisis of “identity versus role confusion” was resolved (in addition to how the earlier developmental crises in infancy and childhood were resolved). The young adult might be afraid to get too close to someone else and lose her or his sense of self, or the young adult might define her or himself in terms of another person. Intimate relationships are more difficult if one is still struggling with identity. Achieving a sense of identity is a life-long process, but there are periods of identity crisis and stability. And, according to Erikson, having some sense of identity is essential for intimate relationships. Although, consider what that would mean for previous generations of women who may have defined themselves through their husbands and marriages, or for Eastern cultures today that value interdependence rather than independence.

People in early adulthood (the 20s through 40) are concerned with intimacy vs. isolation. After we have developed a sense of self in adolescence, we are ready to share our life with others. However, if other stages have not been successfully resolved, young adults may have trouble developing and maintaining successful relationships with others. Erikson said that we must have a strong sense of self before we can develop successful intimate relationships. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.

Friendships as a source of intimacy

In our twenties, intimacy needs may be met in friendships rather than with partners. This is especially true in the United States today as many young adults postpone making long-term commitments to partners either in marriage or in cohabitation. The kinds of friendships shared by women tend to differ from those shared by men (Tannen, 1990). Friendships between men are more likely to involve sharing information, providing solutions, or focusing on activities rather than discussing problems or emotions. Men tend to discuss opinions or factual information or spend time together in an activity of mutual interest. Friendships between women are more likely to focus on sharing weaknesses, emotions, or problems. Women talk about difficulties they are having in other relationships and express their sadness, frustrations, and joys. These differences in approaches could lead to problems when men and women come together. She may want to vent about a problem she is having; he may want to provide a solution and move on to some activity. But when he offers a solution, she thinks he does not care! Effective communication is the key to good relationships.

Many argue that other-sex friendships become more difficult for heterosexual men and women because of the unspoken question about whether the friendships will lead to a romantic involvement. Although common during adolescence and early adulthood, these friendships may be considered threatening once a person is in a long-term relationship or marriage. Consequently, friendships may diminish once a person has a partner or single friends may be replaced with couple friends.

Personality

Beyond providing insights into the general outline of adult personality development, Roberts et al. (2006) found that young adulthood (the period between the ages of 18 and the late 20s) was the most active time in the lifespan for observing average changes, although average differences in personality attributes were observed across the lifespan. Such a result might be surprising in light of the intuition that adolescence is a time of personality change and maturation. However, young adulthood is typically a time in the lifespan that includes a number of life changes in terms of finishing school, starting a career, committing to romantic partnerships, and parenthood (Donnellan, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Rindfuss, 1991). Finding that young adulthood is an active time for personality development provides circumstantial evidence that adult roles might generate pressures for certain patterns of personality development. Indeed, this is one potential explanation for the maturity principle of personality development.

It should be emphasized again that average trends are summaries that do not necessarily apply to all individuals. Some people do not conform to the maturity principle. The possibility of exceptions to general trends is the reason it is necessary to study individual patterns of personality development. The methods for this kind of research are becoming increasingly popular (e.g., Vaidya, Gray, Haig, Mroczek, & Watson, 2008) and existing studies suggest that personality changes differ across people (Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). These new research methods work best when researchers collect more than two waves of longitudinal data covering longer spans of time. This kind of research design is still somewhat uncommon in psychological studies but it will likely characterize the future of research on personality stability.

What you’ll learn to do: examine relationships in early adulthood

We have learned from Erikson that the psychosocial developmental task of early adulthood is “intimacy versus isolation” and if resolved relatively positively, it can lead to the virtue of “love.” In this section, we will look more closely at relationships in early adulthood, particularly in terms of love, dating, cohabitation, marriage, and parenting.

Learning outcomes

- Describe some of the factors related to attraction in relationships

- Apply Sternberg’s theory of love to relationships

- Summarize attachment theory in adulthood

- Describe trends and norms in dating, cohabitation, and marriage in the United States

Attraction and Love

Attraction

Why do some people hit it off immediately? Or decide that the friend of a friend was not likable? Using scientific methods, psychologists have investigated factors influencing attraction and have identified a number of variables, such as similarity, proximity (physical or functional), familiarity, and reciprocity, that influence with whom we develop relationships.

Proximity

Often we “stumble upon” friends or romantic partners; this happens partly due to how close in proximity we are to those people. Specifically, proximity or physical nearness has been found to be a significant factor in the development of relationships. For example, when college students go away to a new school, they will make friends consisting of classmates, roommates, and teammates (i.e., people close in proximity). Proximity allows people the opportunity to get to know one other and discover their similarities—all of which can result in a friendship or intimate relationship. Proximity is not just about geographic distance, but rather functional distance, or the frequency with which we cross paths with others. For example, college students are more likely to become closer and develop relationships with people on their dorm-room floors because they see them (i.e., cross paths) more often than they see people on a different floor. How does the notion of proximity apply in terms of online relationships? Deb Levine (2000) argues that in terms of developing online relationships and attraction, functional distance refers to being at the same place at the same time in a virtual world (i.e., a chat room or Internet forum)—crossing virtual paths.

Familiarity

One of the reasons why proximity matters to attraction is that it breeds familiarity; people are more attracted to that which is familiar. Just being around someone or being repeatedly exposed to them increases the likelihood that we will be attracted to them. We also tend to feel safe with familiar people, as it is likely we know what to expect from them. Dr. Robert Zajonc (1968) labeled this phenomenon the mere-exposure effect. More specifically, he argued that the more often we are exposed to a stimulus (e.g., sound, person) the more likely we are to view that stimulus positively. Moreland and Beach (1992) demonstrated this by exposing a college class to four women (similar in appearance and age) who attended different numbers of classes, revealing that the more classes a woman attended, the more familiar, similar, and attractive she was considered by the other students.

There is a certain comfort in knowing what to expect from others; consequently, research suggests that we like what is familiar. While this is often on a subconscious level, research has found this to be one of the most basic principles of attraction (Zajonc, 1980). For example, a young man growing up with an overbearing mother may be attracted to other overbearing women not because he likes being dominated but rather because it is what he considers normal (i.e., familiar).

Similarity

When you hear about celebrity couples such as Kim Kardashian and Kanye West, do you shake your head thinking “this won’t last”? It is probably because they seem so different. While many make the argument that opposites attract, research has found that is generally not true; similarity is key. Sure, there are times when couples can appear fairly different, but overall we like others who are like us. Ingram and Morris (2007) examined this phenomenon by inviting business executives to a cocktail mixer, 95% of whom reported that they wanted to meet new people. Using electronic name tag tracking, researchers revealed that the executives did not mingle or meet new people; instead, they only spoke with those they already knew well (i.e., people who were similar).

When it comes to marriage, research has found that couples tend to be very similar, particularly when it comes to age, social class, race, education, physical attractiveness, values, and attitudes (McCann Hamilton, 2007; Taylor, Fiore, Mendelsohn, & Cheshire, 2011). This phenomenon is known as the matching hypothesis (Feingold, 1988; Mckillip & Redel, 1983). We like others who validate our points of view and who are similar in thoughts, desires, and attitudes.

Reciprocity

Another key component in attraction is reciprocity; this principle is based on the notion that we are more likely to like someone if they feel the same way toward us. In other words, it is hard to be friends with someone who is not friendly in return. Another way to think of it is that relationships are built on give and take; if one side is not reciprocating, then the relationship is doomed. Basically, we feel obliged to give what we get and to maintain equity in relationships. Researchers have found that this is true across cultures (Gouldner, 1960).

Love

Is all love the same? Are there different types of love? Examining these questions more closely, Robert Sternberg’s (2004; 2007) work has focused on the notion that all types of love are comprised of three distinct areas: intimacy, passion, and commitment. Intimacy includes caring, closeness, and emotional support. The passion component of love is comprised of physiological and emotional arousal; these can include physical attraction, emotional responses that promote physiological changes, and sexual arousal. Lastly, commitment refers to the cognitive process and decision to commit to love another person and the willingness to work to keep that love over the course of your life. The elements involved in intimacy (caring, closeness, and emotional support) are generally found in all types of close relationships—for example, a mother’s love for a child or the love that friends share. Interestingly, this is not true for passion. Passion is unique to romantic love, differentiating friends from lovers. In sum, depending on the type of love and the stage of the relationship (i.e., newly in love), different combinations of these elements are present. Taking this theory a step further, anthropologist Helen Fisher explained that she scanned the brains (using fMRI) of people who had just fallen in love and observed that their brain chemistry was “going crazy,” similar to the brain of an addict on a drug high (Cohen, 2007). Specifically, serotonin production increased by as much as 40% in newly-in-love individuals. Further, those newly in love tended to show obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Conversely, when a person experiences a breakup, the brain processes it in a similar way to quitting a heroin habit (Fisher, Brown, Aron, Strong, & Mashek, 2009). Thus, those who believe that breakups are physically painful are correct! Another interesting point is that long-term love and sexual desire activate different areas of the brain. More specifically, sexual needs activate the part of the brain that is particularly sensitive to innately pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs (i.e., the striatum—a rather simplistic reward system), whereas love requires conditioning—it is more like a habit. When sexual needs are rewarded consistently, then love can develop. In other words, love grows out of positive rewards, expectancies, and habit (Cacioppo, Bianchi-Demicheli, Hatfield & Rapson, 2012).

Attachment Theory in Adulthood

The need for intimacy, or close relationships with others, is universal and persistent across the lifespan. What our adult intimate relationships look like actually stems from infancy and our relationship with our primary caregiver (historically our mother)—a process of development described by attachment theory, which you learned about in the module on infancy. Recall that according to attachment theory, different styles of caregiving result in different relationship “attachments.”

For example, responsive mothers—mothers who soothe their crying infants—produce infants who have secure attachments (Ainsworth, 1973; Bowlby, 1969). About 60% of all children are securely attached. As adults, secure individuals rely on their working models—concepts of how relationships operate—that were created in infancy, as a result of their interactions with their primary caregiver (mother), to foster happy and healthy adult intimate relationships. Securely attached adults feel comfortable being depended on and depending on others.

As you might imagine, inconsistent or dismissive parents also impact the attachment style of their infants (Ainsworth, 1973), but in a different direction. In early studies on attachment style, infants were observed interacting with their caregivers, followed by being separated from them, then finally reunited. About 20% of the observed children were “resistant,” meaning they were anxious even before, and especially during, the separation; and 20% were “avoidant,” meaning they actively avoided their caregiver after separation (i.e., ignoring the mother when they were reunited). These early attachment patterns can affect the way people relate to one another in adulthood. Anxious-resistant adults worry that others don’t love them, and they often become frustrated or angry when their needs go unmet. Anxious-avoidant adults will appear not to care much about their intimate relationships and are uncomfortable being depended on or depending on others themselves.

| Table 1. Types of Early Attachment and Adult Intimacy | |

| Secure | “I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don’t often worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me,” |

| Anxious-avoidant | “I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, love partners want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.” |

| Anxious-resistant | “I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me or won’t want to stay with me. I want to merge completely with another person, and this desire sometimes scares people away.” |

The good news is that our attachment can be changed. It isn’t easy, but it is possible for anyone to “recover” a secure attachment. The process often requires the help of a supportive and dependable other, and for the insecure person to achieve coherence—the realization that his or her upbringing is not a permanent reflection of character or a reflection of the world at large, nor does it bar him or her from being worthy of love or others of being trustworthy (Treboux, Crowell, & Waters, 2004).

You can watch this video “What is Your Attachment Style?” from The School of Life to learn more.

Applications of Sternberg’s Theory

Do these types of love mean anything? Is love necessary or helpful for reproduction in humans?

One study tested this hypothesis using Sternberg’s Triangular Love scale as their operational definition of love. The three components of passion, commitment, and intimacy were measured in a traditional hunter-gatherer tribe in Tanzania, and researchers gathered data about which type of relationship was most correlated with successful reproduction.

Try to predict the results of the study.

You were probably were able to discern that this study examines the correlation between types of relationships and reproductive success, or the number of children a woman has. In psychology, we learn that correlation does NOT equal causation, so just because a person is in a committed relationship, this does not mean they will have children.

So what does correlation really mean? It means there is a relationship between the variables. Remember, that with positive correlation, as one variable increases, so does the other. In a negative correlation, as one variable increases the other decreases.

Trends in Dating, Cohabitation, and Marriage

Dating

In general, traditional dating among teens and those in their early twenties has been replaced with more varied and flexible ways of getting together (and technology with social media, no doubt, plays a key role). The Friday night date with dinner and a movie that may still be enjoyed by those in their 30s gives way to less formal, more spontaneous meetings that may include several couples or a group of friends. Two people may get to know each other and go somewhere alone. How would you describe a “typical” date? Who calls, texts, or face times? Who pays? Who decides where to go? What is the purpose of the date? In general, greater planning is required for people who have additional family and work responsibilities.

Dating and the Internet

The ways people are finding love has changed with the advent of the Internet. In a poll, 49% of all American adults reported that either they or someone they knew had dated a person they met online (Madden & Lenhart, 2006). As Finkel and colleagues (2007) found, social networking sites, and the Internet generally, perform three important tasks. Specifically, sites provide individuals with access to a database of other individuals who are interested in meeting someone. Dating sites generally reduce issues of proximity, as individuals do not have to be close in proximity to meet. Also, they provide a medium in which individuals can communicate with others. Finally, some Internet dating websites advertise special matching strategies, based on factors such as personality, hobbies, and interests, to identify the “perfect match” for people looking for love online. In general, scientific questions about the effectiveness of Internet matching or online dating compared to face-to-face dating remain to be answered.

It is important to note that social networking sites have opened the doors for many to meet people that they might not have ever had the opportunity to meet; unfortunately, it now appears that the social networking sites can be forums for unsuspecting people to be duped. In 2010 a documentary, Catfish, focused on the personal experience of a man who met a woman online and carried on an emotional relationship with this person for months. As he later came to discover, though, the person he thought he was talking and writing with did not exist. As Dr. Aaron Ben-Zeév stated, online relationships leave room for deception; thus, people have to be cautious.

Cohabitation

Cohabitation is an arrangement where two people who are not married live together. They often involve a romantic or sexually intimate relationship on a long-term or permanent basis. Such arrangements have become increasingly common in Western countries during the past few decades, being led by changing social views, especially regarding marriage, gender roles, and religion. Today, cohabitation is a common pattern among people in the Western world. In Europe, the Scandinavian countries have been the first to start this leading trend, although many countries have since followed. Mediterranean Europe has traditionally been very conservative, with religion playing a strong role. Until the mid-1990s, cohabitation levels remained low in this region, but have since increased. Cohabitation is common in many countries, with the Scandinavian nations of Iceland, Sweden, and Norway reporting the highest percentages, and more traditional countries like India, China, and Japan reporting low percentages (DeRose, 2011).

In countries where cohabitation is increasingly common, there has been speculation as to whether or not cohabitation is now part of the natural developmental progression of romantic relationships: dating and courtship, then cohabitation, engagement, and finally marriage. Though, while many cohabitating arrangements ultimately lead to marriage, many do not.

How prevalent is cohabitation today in the United States? According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2018), cohabitation has been increasing, while marriage has been decreasing in young adulthood. As seen in the graph below, over the past 50 years, the percentage of 18 to 24-year-olds in the U.S. living with an unmarried partner has gone from 0.1 percent to 9.4 percent, while living with a spouse has gone from 39.2 percent to 7 percent. More 18 to 24-year-olds live with an unmarried partner now than with a married partner.

While the percent living with a spouse is still higher than the percent living with an unmarried partner among 25 to 34-year-olds today, the next graph clearly shows a similar pattern of decline in marriage and increase in cohabitation over the last five decades. The percent living with a spouse in this age group today is only half of what it was in 1968 (40.3 percent vs. 81.5 percent), while the percent living with an unmarried partner rose from 0.2 percent to 14.8 percent in this age group. Another way to look at some of the data is that only 30% of today’s 18 to 34-year-olds in the U.S. are married, compared with almost double that, 59 percent forty years ago (1978). The marriage rates for less-educated young adults (who tend to have lower income) have fallen at faster rates than those of better educated young adults since the 1970s. Past and present economic climate are key factors; perhaps more couples are waiting until they can afford to get married, financially. Gurrentz (2018) does caution that there are limitations of the measures of cohabitation, particularly in the past.

How long do cohabiting relationships last?

Cohabitation tends to last longer in European countries than in the United States. Half of cohabiting relationships in the U. S. end within a year; only 10 percent last more than 5 years. These short-term cohabiting relationships are more characteristics of people in their early 20s. Many of these couples eventually marry. Those who cohabit for more than five years tend to be older and more committed to the relationship. Cohabitation may be preferable to marriage for a number of reasons. For partners over 65, cohabitation is preferable to marriage for practical reasons. For many of them, marriage would result in a loss of Social Security benefits and consequently is not an option. Others may believe that their relationship is more satisfying because they are not bound by marriage.

Think About it

Do you think that you will cohabitate before marriage? Or did you cohabitate? Why or why not? Does your culture play a role in your decision? Does what you learned in this module change your thoughts on this practice?

Same-Sex Couples

As of 2019, same-sex marriage is legal in 28 countries and counting. Many other countries either recognize same-sex couples for the purpose of immigration, grant rights for domestic partnerships, or grant common law marriage status to same-sex couples.

Same-sex couples struggle with concerns such as the division of household tasks, finances, sex, and friendships as do heterosexual couples. One difference between same-sex and heterosexual couples, however, is that same-sex couples have to live with the added stress that comes from social disapproval and discrimination. And continued contact with an ex-partner may be more likely among homosexuals and bisexuals because of the closeness of the circle of friends and acquaintances.

The number of adults who remain single has increased dramatically in the last 30 years. We have more people who never marry, more widows, and more divorcees driving up the number of singles. Singles represent about 25 percent of American households. Singlehood has become a more acceptable lifestyle than it was in the past and many singles are very happy with their status. Whether or not a single person is happy depends on the circumstances of their remaining single.

Stein’s Typology of Singles

Many of the research findings of singles reveal that they are not all alike. Happiness with one’s status depends on whether the person is single by choice and whether the situation is permanent. Let’s look at Stein’s (1981) four categories of singles for a better understanding of this.

- Voluntary temporary singles: These are younger people who have never been married and divorced people who are postponing marriage and remarriage. They may be more involved in careers or getting an education or just wanting to have fun without making a commitment to any one person. They are not quite ready for that kind of relationship. These people tend to report being very happy with their single status.

- Voluntary permanent singles: These individuals do not want to marry and aren’t intending to marry. This might include cohabiting couples who don’t want to marry, priests, nuns, or others who are not considering marriage. Again, this group is typically single by choice and understandably more contented with this decision.

- Involuntary temporary: These are people who are actively seeking mates. They hope to marry or remarry and may be involved in going on blind dates, seeking a partner on the internet, or placing “getting personal” aids in search of a mate. They tend to be more anxious about being single.

- Involuntary permanent: These are older divorced, widowed, or never-married people who wanted to marry but have not found a mate and are coming to accept singlehood as a probable permanent situation. Some are bitter about not having married while others are more accepting of how their life has developed.

Engagement and Marriage

Most people will marry in their lifetime. In the majority of countries, 80% of men and women have been married by the age of 49 (United Nations, 2013). Despite how common marriage remains, it has undergone some interesting shifts in recent times. Around the world, people are tending to get married later in life or, increasingly, not at all. People in more developed countries (e.g., Nordic and Western Europe), for instance, marry later in life—at an average age of 30 years. This is very different than, for example, the economically developing country of Afghanistan, which has one of the lowest average-age statistics for marriage—at 20.2 years (United Nations, 2013). Another shift seen around the world is a gender gap in terms of age when people get married. In every country, men marry later than women. Since the 1970s, the average age of marriage has increased for both women and men.

As illustrated, the courtship process can vary greatly around the world. So too can an engagement—a formal agreement to get married. Some of these differences are small, such as on which hand an engagement ring is worn. In many countries, it is worn on the left, but in Russia, Germany, Norway, and India, women wear their ring on their right. There are also more overt differences, such as who makes the proposal. In India and Pakistan, it is not uncommon for the family of the groom to propose to the family of the bride, with little to no involvement from the bride and groom themselves. In most Western industrialized countries, it is traditional for the male to propose to the female. What types of engagement traditions, practices, and rituals are common where you are from? How are they changing?

Contemporary young adults in the United States are waiting longer than before to marry. The median age of entering marriage in the United States is 27 for women and 29 for men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011). This trend in delays of young adults taking on adult roles and responsibilities is discussed in our earlier section about “emerging adulthood” or the transition from adolescence to adulthood identified by Arnett (2000).

A fair exchange

Social exchange theory suggests that people try to maximize rewards and minimize costs in social relationships. Each person entering the marriage market comes equipped with assets and liabilities or a certain amount of social currency with which to attract a prospective mate. For men, assets might include earning potential and status while for women, assets might include physical attractiveness and youth.

Customers in the “marriage market” do not look for a “good deal,” however. Rather, most look for a relationship that is mutually beneficial or equitable. One of the reasons for this is because most a relationship in which one partner has far more assets than the other will result in power disparities and a difference in the level of commitment from each partner. According to Waller’s principle of least interest, the partner who has the most to lose without the relationship (or is the most dependent on the relationship) will have the least amount of power and is in danger of being exploited. A greater balance of power, then, may add stability to the relationship.

Societies specify through both formal and informal rules who is an appropriate mate. Consequently, mate selection is not completely left to the individual. Rules of endogamy indicate within which groups we should marry. For example, many cultures specify that people marry within their own race, social class, age group, or religion. These rules encourage homogamy or marriage between people who share social characteristics (the opposite is known as heterogamy). The majority of marriages in the U.S. are homogamous with respect to race, social class, age, and to a lesser extent, religion.

In a comparison of educational homogamy in 55 countries, Smits (2003) found strong support for higher-educated people marrying other highly educated people. As such, education appears to be a strong filter people use to help them select a mate. The most common filters we use—or, put another way, the characteristics we focus on most in potential mates—are age, race, social status, and religion (Regan, 2008). Other filters we use include compatibility, physical attractiveness (we tend to pick people who are as attractive as we are), and proximity (for practical reasons, we often pick people close to us) (Klenke-Hamel & Janda, 1980).

According to the filter theory of mate selection, the pool of eligible partners becomes narrower as it passes through filters used to eliminate members of the pool (Kerckhoff & Davis, 1962). One such filter is propinquity or geographic proximity. Mate selection in the United States typically involves meeting eligible partners face to face. Those with whom one does not come into contact are simply not contenders (though this has been changing with the Internet). Race and ethnicity is another filter used to eliminate partners. Although interracial dating has increased in recent years and interracial marriage rates are higher than before, interracial marriage still represents only 5.4 percent of all marriages in the United States. Physical appearance is another feature considered when selecting a mate. Age, social class, and religion are also criteria used to narrow the field of eligibles. Thus, the field of eligibles becomes significantly smaller before those things we are most conscious of such as preferences, values, goals, and interests, are even considered.

Arranged Marriages

In some cultures, however, it is not uncommon for the families of young people to do the work of finding a mate for them. For example, the Shanghai Marriage Market refers to the People’s Park in Shanghai, China—a place where parents of unmarried adults meet on weekends to trade information about their children in an attempt to find suitable spouses for them (Bolsover, 2011). In India, the marriage market refers to the use of marriage brokers or marriage bureaus to pair eligible singles together (Trivedi, 2013). To many Westerners, the idea of arranged marriage can seem puzzling. It can appear to take the romance out of the equation and violate values about personal freedom. On the other hand, some people in favor of arranged marriage argue that parents are able to make more mature decisions than young people.

While such intrusions may seem inappropriate based on your upbringing, for many people of the world such help is expected, even appreciated. In India for example, “parental arranged marriages are largely preferred to other forms of marital choices” (Ramsheena & Gundemeda, 2015, p. 138). Of course, one’s religious and social caste plays a role in determining how involved family may be.

The new life stage of emerging adulthood has spread rapidly in the past half-century and is continuing to spread. Now that the transition to adulthood is later than in the past, is this change positive or negative for emerging adults and their societies? Certainly, there are some negatives. It means that young people are dependent on their parents for longer than in the past, and they take longer to become fully contributing members of their societies. A substantial proportion of them have trouble sorting through the opportunities available to them and struggle with anxiety and depression, even though most are optimistic. However, there are advantages to having this new life stage as well. By waiting until at least their late twenties to take on the full range of adult responsibilities, emerging adults are able to focus on obtaining enough education and training to prepare themselves for the demands of today’s information- and technology-based economy. Also, it seems likely that if young people make crucial decisions about love and work in their late twenties or early thirties rather than their late teens and early twenties, their judgment will be more mature and they will have a better chance of making choices that will work out well for them in the long run.

What can societies do to enhance the likelihood that emerging adults will make a successful transition to adulthood? One important step would be to expand the opportunities for obtaining tertiary education. The tertiary education systems of OECD countries were constructed at a time when the economy was much different, and they have not expanded at the rate needed to serve all the emerging adults who need such education. Furthermore, in some countries, such as the United States, the cost of tertiary education has risen steeply and is often unaffordable to many young people. In non-industrialized countries, tertiary education systems are even smaller and less able to accommodate their emerging adults. Across the world, societies would be wise to strive to make it possible for every emerging adult to receive tertiary education, free of charge. There could be no better investment for preparing young people for the economy of the future.

Additional Supplemental Resources

Websites

- Society for the Study of Emerging Adulthood

- SSEA is a multidisciplinary, international organization with a focus on theory and research related to emerging adulthood, which includes the age range of approximately 18 through 29 years. The website includes information on topics, events, and publications pertaining to emerging adults from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and countries.

- On the Cusp of Adulthood: What we know about Gen Z so far

- Aside from the unique set of circumstances in which Gen Z is approaching adulthood, what do we know about this new generation? Pew Research Center

- Article: The People Who Prioritize a Friendship Over Romance – The Atlantic

- What is friendship, and not marriage, was at the center of life?

Videos

-

Why does it take so long to grow up today? | Jeffrey Jensen Arnett | TEDxPSU

- It takes so long to “grow up” today—finish education, find a stable job, get married—that it makes sense to think of it as a new life stage, emerging adulthood, in between adolescence and young adulthood. But why? Arnett coined the phrase emerging adulthood, the phase of life between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood.

- Why 30 is Not the New 20 TED talk

- Clinical psychologist Meg Jay has a bold message for twentysomethings: Contrary to popular belief, your 20s are not a throwaway decade. In this provocative talk, Jay says that just because marriage, work, and kids are happening later in life, doesn’t mean you can’t start planning now.

- The Love Competition

- The World’s First Annual Love Competition. Because “Love is a feeling you have for someone you have feelings about.”

Journal Articles

- Grahe, J. E., Corker, K. S., Schmolesky, M., Cramblet Alvarez, L. D., McFall, J. P., Lazzara, J., & Kemp, A. (2018, May 17). Do Institutional Characteristics Predict Markers of Adulthood? A Close Replication of Fosse and Toyokawa (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696818810268

- Faas, Caitlin & Mcfall, Joseph & Peer, Justin & Schmolesky, Matthew & Chalk, Holly & Hermann, Anthony & Chopik, William & Leighton, Dana & Lazzara, Julie & Kemp, Andrew & DiLillio, Vicki & Grahe, Jon. (2018). Emerging Adulthood MoA/IDEA-8 Scale Characteristics From Multiple Institutions. Emerging Adulthood. 216769681881119. 10.1177/2167696818811192.