Introduction to Native American Accounts by Jennifer Kurtz and Wendy Kurant

Native American Accounts

Wendy Kurant and Jenifer Kurtz

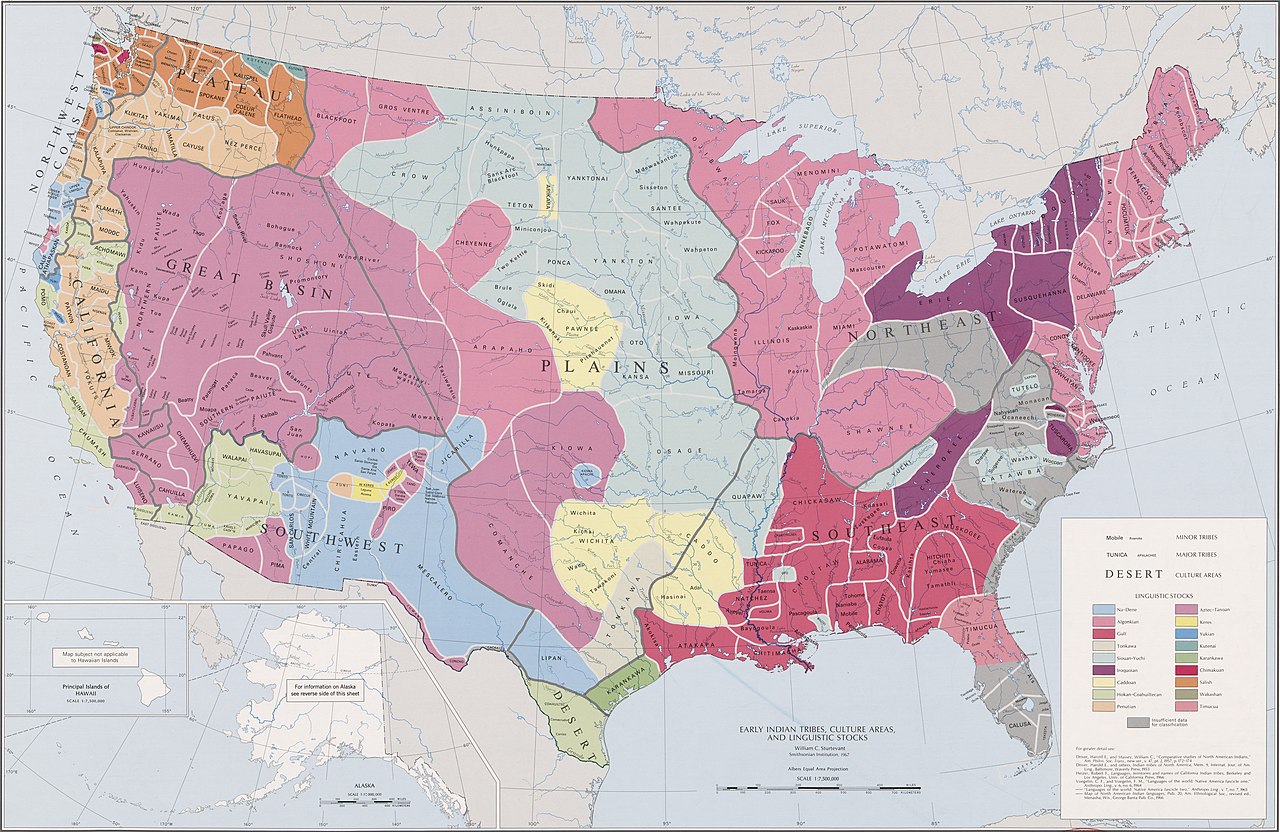

It is well to bear in mind that the selections here should not be understood as representative of Native American culture as a whole. There are thousands of different Native American tribes, all with distinct practices. It would not be possible in the space of a typical anthology to represent just the tribes with whom the colonists had the most contact during the early years of European settlement, or even to say with any precision exactly how many tribes the colonists did interact with since European colonists were often unable to distinguish among different tribes. Additionally, we must realize that these works come to us with omissions and mediations. Many Native American tales are performative as well as oral—the meanings of the words supplemented by expressions, movements, and shared cultural assumptions—and so the words alone do not represent their full significance. That being said, the examples of Native American accounts that follow give us some starting points to consider the different ways in which cultures explain themselves to themselves.

First among a culture’s stories are the tales of how the earth was created and how its geographical features and peoples came to be. The Native American creation stories collected here demonstrate two significant tropes within Native American creation stories: the Earth Diver story and the Emergence story. Earth Diver stories often begin with a pregnant female falling from a sky world into a watery world, such as the ones here from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people of the eastern United States and from the Cherokee people from the southern United States. Various animals then work together to create dry land so that the woman may give birth there, starting the process of creating the familiar world and its population. With Emergence stories, here represented by the Zuni creation story, animals and people emerge from within the earth, a distinction from the Earth Diver story that is likely connected to the topography familiar to this tribe from the southwestern United States. Creation stories feature a “culture hero,” an extraordinary being who is instrumental in shaping the world in its current form. Other examples in addition to the works here are the Wampanoag culture hero Moshup or Maushop, a giant who shared his meals of whale with the tribe and created the island of Nantucket out of tobacco ash, and Masaw, the Hopi skeleton man and Lord of the Dead who helped the tribe by teaching them agriculture in life and caring for them in death. Some creation tales show similarities to Judeo‑Christian theology and suggest parallel development or European influence, quite possible since many of these stories were not put into writing until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Some Native American creation tales show motifs of movement from chaos to duality to order and beings of creation and destruction paired together, themes also found in European accounts of creation. However, these tales feature significant differences to the European way of understanding the world. These tales often show the birth of the land and of the people as either contemporaneous events, as with the Earth Diver stories, or as the former figuratively birthing the latter, as with the Emergence stories. This suggests the context for some tribes’ beliefs in the essentialness of land to tribal and personal identity. As Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna Pueblo) asserts in The Sacred Hoop (1986), “The land is not really the place (separate from ourselves) where we act out the drama of our isolate destinies . . . It is rather a part of our being, dynamic, significant, real.” In addition, Native American creation tales often depict the relationship between man and animals in ways sharply different from European assumptions. In the Haudenosaunee tale and many other Earth Diver tales like it, animals and cultural heroes create the earth and its distinctive features collaboratively.

Like creation stories, Native American trickster stories fulfill an explanatory function about the world; they also explain why social codes exist and why they are needed. The trickster character—often represented as an animal such as a coyote, a raven, or a hare—is a figure of scatological humor, frequently focused on fulfilling and over‑fulfilling physical needs to the detriment of those around him. However, above all things the trickster represents fluid boundaries. The trickster can shift between sexes, interacts with both humans and animals, rarely settles down for any period of time, and is crafty and foolish at the same time. Furthermore, the Trickster transgresses what is socially acceptable and often what is physically possible. In one of the best known trickster cycle, that of the Winnebago tribe originating in the Wisconsin region, the trickster Wakdjunkaga has a detachable penis that can act autonomously and sometimes resides in a box. These tales entertain but also function as guides to acceptable social behavior. Through the mishaps the trickster causes and the mishaps s/he suffers, the trickster tends to reinforce social boundaries as much as s/he challenges them and also can function as a culture hero. Much like the culture heroes described previously, the Winnebago trickster Wakdjunkaga also benefits the tribe. In the last tale of the cycle, s/he makes the Mississippi River Valley safe for occupation by killing malevolent spirits and moving a waterfall.

As is apparent in both the creation stories and the Trickster stories, Native American cultures did not differentiate between animal behavior and human behavior to the extent that Europeans did. While the European concept of the Great Chain of Being established animals as inferior to humans and the Bible was understood to grant man dominion over the animals, the Native American stories to follow suggest a sense of equality with the animals and the rest of nature. Animals contributed to the creation of the world upon which humans live, were able to communicate with humans until they chose not to, and followed (or refused to follow) the same social codes as humans, such as meeting in councils to discuss problems as a group and agreeing together on a course of action. Nonetheless, like with the laxative bulb story, there is tension between the helpful and harmful aspects of nature, and these works teach the lesson that nature must be given due respect lest one lose its benefits and suffer its anger.

“In fourteen hundred ninety‑two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue”: the European perspective on the first contact between Native peoples and European explorers has been taught to Americans from pre‑school onward, but the Native American perspective on these events is less familiar. Just like their counterparts, Native American depictions of first contact with European explorers situated them within their accustomed natural, spiritual, and social contexts. The explorers’ large ships were interpreted as whales, houses, or islands; their paler complexions were a sign of illness or divinity. The gifts or drinks offered by the strangers are accepted out of politeness and social custom, not naiveté or superstition. As these tales were recorded with hindsight, they often ruefully trace how these explorers and colonists disingenuously relied on the natives’ help while appropriating more and more land to themselves and their introduction of alcohol and European commodities into native culture.

Source Text:

Becoming America, Wendy Kurant, ed., CC-BY-SA

Image Credit:

Early Indian Languages USA, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44753