Introduction to Pontiac by Samantha Zivic

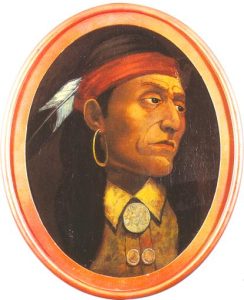

Pontiac (1720-1769)

Pontiac was a leader of the Ottawa (aka Odawa) tribe who lived during the period 1720-1769. He spent his life in the Great Lakes region in the area of what is today the United States and Canada (Michigan and Ontario). Not a great deal is known about Pontiac prior to the event that occurred in 1763 which became the focal point of his life (at least in the context of how history remembers him). In his younger years, Pontiac rose to power as a military leader within the tribe.

The time period in which Pontiac lived was one filled with strife and war involving a diversity of Indian tribes, British American colonies, and New France colonies. The French and Indian War took place during the years 1754-1763 and was, perhaps, the central event of the era. Some tribes sided with the British Americans and some sided with the French. In fact, the war is also referred to as the Seven Years War by some–so it is clear that even the name of a conflict is dependent on what perspective one has on who you believe are the aggressors in war. Contrast this to our own use of the term “Civil War” (a name used by the North) and the “War of Northern Aggression” (often used by those from the South). What is important to grasp is that Pontic lived in a time and place of conflict amongst a diversity of peoples.

Pontiac’s seminal “Speech at Detroit” occurred on May 5th, 1763 and was delivered before a group that included Pontiac’s fellow Ottawa tribesmen as well as members of the Potawatomie and Huron tribes. It was a call-to-arms and certainly a “pep rally” as he made the case for war. In the speech, Pontiac begins:

“It is important for us, my brothers, that we exterminate from our lands this nation which seeks only to destroy us. You see as well as I do that we can no longer supply our needs, as we have

done from our brothers, the French. The English sell us goods twice as dear as the French do, and their goods do not last.”

Clearly, Pontiac was not happy with the way the British treated and behaved towards his people in the same way that the French treated them. On the one hand he refers to the French as “our brothers”, while the British must be “exterminated”. He is also criticizing the quality of British goods when compared to those that the French have traded with the tribes. Certainly, this is an attempt to make a real-world point to the listeners as to which side would make the best partner and ally. His words are meant to inspire those who might join in the conflict by giving concrete examples of past abuses and future benefits.

Pontiac drives home the urgency of their actions with the following remarks:

“All the nations who are our brothers attack them – why should we not strike too? Are we not

men like them? Have I now shown you the wampum belts [beaded belts symbolizing an

agreement or treaty] which I received from our great father, the Frenchman [King Louis XV]?

He tells us to strike them. Why do we not listen to his words? What do we fear? It is time. “

It is here that Pontiac makes his final plea in what, ultimately, was a fairly short speech. Many of our brothers from other tribes are joining in this battle—so why shouldn’t we? Even in those days, human nature was that same as it is today in that it is always easier to join an activity that many others are also involved in (i.e. the old “strength in numbers” adage). Pontiac used this technique to almost imply that they would be crazy not to participate.

He goes on to say very positive things about the leader of France—King Louis the 15th. The wampum belts he refers to signify the treaties and alliances that the Indians already have with France. By using the term “our great father” in reference to the King, he is showing great honor to another leader—a leader who also is sending out the very same message that Pontiac is trying to convey.

Pontiac’s words also seem to give us some background on the mindset of his listeners. Apparently, not everyone was “on board” with the idea of attacking Fort Detroit. He speaks of the fear that many of them felt. No doubt, the reality that death might be a consequence of the attack led many to hesitate. But like any good orator, Pontiac demonstrated that acknowledging the viewpoint of his listeners and letting them know that he understands their perspective is an effective way to motivate others to act.

Pontiac concludes his remarks with a simple yet powerful statement: “It is time.” Indeed, it is!

Two days later on May 7th, 1763, Pontiac and his men (approximately 300) began their attack on Fort Detroit which ultimately failed. Over the next two months, a series of battles in the region that included Fort Detroit as well as several other forts ensued. Pontiac and various other related bands of warriors had a mixture of successes and failures—in the end falling short of their goal of capturing the British occupied Forts they set out to take. Pontiac went on to become an even more influential voice in the region by inspiring others to take up arms against the British Americans.

Pontiac survived all the battles that he led. Nonetheless, he was assassinated in April 1769 by an Indian for what was believed to be a revenge killing.