21 Literary Analysis

Literature

When is the last time you read a book for fun? If you were to classify that book, would you call it fiction or literature? This is an interesting separation, with many possible reasons for it. One is that “fiction” and “literature” are regarded as quite different things. “Fiction,” for example, is what people read for enjoyment. “Literature” is what they read for school. Or “fiction” is what living people write and is about the present. “Literature” was written by people (often white males) who have since died and is about times and places that have nothing to do with us. Or “fiction” offers everyday pleasures, but “literature” is to be honored and respected, even though it is boring. Of course, when we put anything on a pedestal, we remove it from everyday life, so the corollary is that literature is to be honored and respected, but it is not to be read, certainly not by any normal person with normal interests.

Sadly, it is the guardians of literature, that is, of the classics, who have done so much to take the life out of literature, to put it on a pedestal and thereby to make it an irrelevant aspect of life. People study literature because they love literature. But what happens too often, especially in colleges, is that teachers forget what it was that first interested them in the study of literature. They forget the joy that they first felt (and perhaps still feel) as they read a new novel or a poem or as they reread a work and saw something new in it. Instead, they erect formidable walls around these literary works, giving the impression that the only access to a work is through deep learning and years of study. Such study is clearly important for scholars, but this kind of scholarship is not the only way, or even necessarily the best way, for most people to approach literature. Instead, it makes the literature seem inaccessible. It makes the literature seem like the province of scholars. “Oh, you have to be smart to read that,” as though Shakespeare or Dickens or Woolf wrote only for English teachers, not for general readers.

What is Literature?

Some Misconceptions about Literature

Why Reading Literature is Important

How to Read Literature

1. Read with a pen in hand! Jot down questions, highlight things you find significant, mark confusing passages, look up unfamiliar words/references, and record first impressions.2. Think critically to form a response.

- The more you know about a story, the more pleasure your reading will provide as you uncover the hidden elements that create the theme of the piece.

- Address your own biases and compare your own experiences with those expressed in the piece.

- Test your positions and thoughts about the piece with what others think by doing research.

While you will have your own individual connection to a piece based on your life experiences, interpreting literature is not a willy nilly process. Each piece has an author who had a purpose in writing the piece–you want to uncover that purpose. As the speaker in the video you watched about how to read literature notes, you, as a reader, also have a role to play. Sometimes you may see something in the text that speaks to you–whether or not the author intended that piece to be there, it still matters to you. However, when writing about literature, it’s important that our observations can be supported by the text itself. Make sure you aren’t reading into the text something that isn’t there. Value the author for who he/she is and appreciate his/her experiences while attempting to create a connection with yourself and your experiences.

Analyzing

To analyze means to break something down into its parts and examine them. Analyzing is a vital skill for successful readers. Analyzing a text involves breaking down its ideas and structure to understand it better, think critically about it, and draw conclusions. In order to most efficiently analyze a fictional text, you can make use of a story map.

Literary Elements

When you read a literary piece of work, one of the best ways to begin an analysis is to review the literary elements that are contained within that story. Several of these elements were mentioned in the previous section on writing a story map. Let’s look a little deeper.

A common approach to analyzing short fiction is to focus on five basic elements: plot , character , setting ,conflict , and theme . The plot of a work of fiction is the series of events and character actions that relate to the central conflict. A character is a person, or perhaps an animal, who participates in the action of the story. The setting of a piece of fiction is the time and place in which the events happen, including the landscape, scenery, buildings, seasons, or weather. The conflict is a struggle between two people or things in a short story. The main character is usually on one side of the central conflict. The theme is the central idea or issue conveyed by the story. These five basic elements combine to form what might be called the overall narrative of the story. In the next section, we will discuss the narrative arc of fiction in more detail. Below are the formal elements of fiction and questions that will help you to read texts actively.

Questions for Active Reading:

Plot

- How does the text present the passing of time?

- Does it present time in a chronological way?

- Or does it present the event in a non-chronological way?

- What verb tenses are used? (i.e. past, present, future)

Character

- How are the characters described?

- Do the characters talk in unique or peculiar ways?

- Are the names of the characters important or meaningful?

- What kind of conflicts emerge between the characters?

Setting

- When and where does the story seem to take place?

- Is there anything important or meaningful in regards to the time of day or time of year the story seems to take place?

- Is there any significance to the atmospheric, environmental, or weather events that take place?

Conflict

- What problem or issue serves as the story’s focus?

- Is the conflict an explicit one between the story’s characters?

- Or is there a larger question or concern that is implied through the story’s narration?

Theme

- What is the relationship between the title of the story and the text?

- What main issue or idea does the story address? (1)

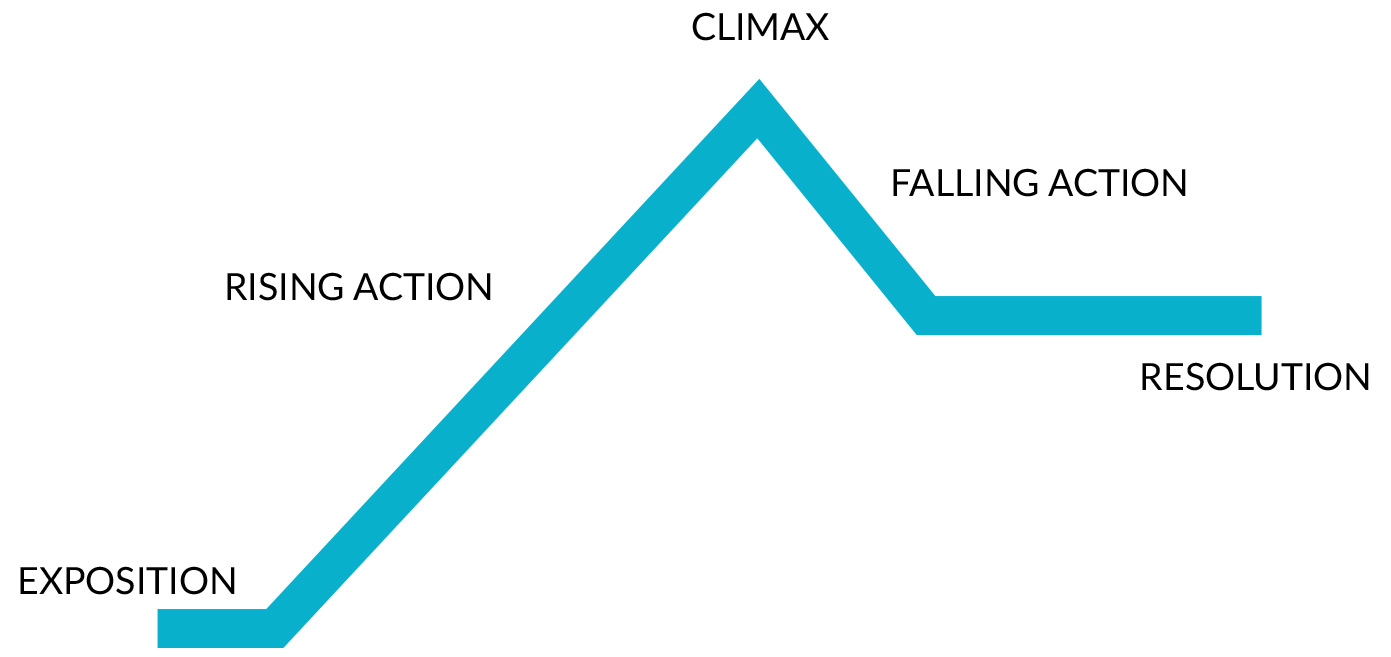

Narrative Arc

The narrative arc — or dramatic structure — of a story may be divided into several phases of development. One traditional method of the analysis of fiction involves identifying five major stages of the development of the plot. The five major stages are known as the exposition (or introduction), the rising action (sometimes referred to as complicating action), the climax (or turning point), the falling action , and the denouement (or resolution).

The exposition of a story introduces characters’ backstory and key information about the setting. With this foundation laid, the dramatic tension then builds, thus creating the rising action of the story through a series of related events that complicate and exacerbate the major conflicts of the story. The turning point of the story occurs at the climax that typically changes the main character’s fate or reveals how the conflict will move toward resolution, either favorably or perhaps tragically. The falling action works to unravel the tension at the core of the major conflict or conflicts in the story and between the characters, although it may include one last twist that impacts the resolution of events. Denouement is derived from the Old French word desnouer (“to untie”); the term suggests that the knot of conflict generating the tension in the story at last is loosened. Of course, not every aspect of the conflict may be resolved or may be resolved to the satisfaction of the reader. Indeed, in some stories, the author may intend that the reader should be left to weigh the validity or even the morality of further outcomes. While these five stages of dramatic structure are very helpful in analyzing fiction, they can be applied too strictly making a story seem like one linear series of events in straight chronological order. Some of the most engaging and well-crafted works of fiction break or interrupt the linear structure of events, perhaps through the manipulation of time (as in the use of flashback or flash-forward ) or through the inclusion of an extended interior monologue (a digression into the interior thoughts, memories, and/or feelings of a particular character). Therefore, readers should be careful not to simplify the plot of a story into an ordered, numerical list of events. The terms protagonist (main character, or hero/heroine) and antagonist (anti-hero/ine) can be helpful in highlighting the roles of the major characters in a story. The story also may unfold through a particular point-of-view , or even through alternating points-of-view. The two most utilized narrative perspectives to consider are first-person point-of-view where the protagonist narrates the story from the voice of “I,” and third-person point-of-view , or omniscient point-of-view, where the narrative refers to each character as “he,” “she,” or “it” thus offering a more distanced perspective on events. Readers may be persuaded, or not, of a narrative’s credibility through point-of-view(s) and/or the presentation of the persona of the narrator (if there is one). A persona is a role that one assumes or displays in public; in literature, it is the presented face or speaking voice of a character. Credibility is the quality of being believed, convincing, or trustworthy. When the credibility of a text is called into question, perhaps as a result of conflicting accounts of events, or detected bias in a point-of-view, the text is said to have an unreliable narrator . Sometimes authors choose to intentionally create an unreliable narrator either to raise suspense, obscure their own position on a subject, or as a means of critiquing a particular cultural or social perspective. Additionally, to analyze a short story more closely, as in poetry, students may also pay attention to the use of figurative language . Figurative language, such as the use of imagery and symbol can be especially significant in fiction. What brings value to one’s analysis is the critical thought that prioritizes which of these many formal elements is most significant to communicating the meaning of the story and connects how these formal elements work together to form the unique whole of a given fictional work.

Common Types of Figurative Language:

Apostrophe — A direct address to a person or object not literally listening; ex: “Oh, Great Mother Nature how you test our spirit…”Allusion — Reference to a well-known object, character, or event, sometimes from another literary work.Hyperbole — Exaggeration used for emphasis.Imagery — Words and phrases that appeal to the senses, particularly sight.Metaphor — A direct comparison of two seemingly dissimilar items (does not use the words like or as ).Onomatopoeia — A word that imitates the sound of the object the word represents.Personification — The attribution of human characteristics to nonhuman places or things.Simile — A comparison of two seemingly dissimilar items using like or as.While it is important to ground our analysis of literature in a close reading based on a detailed understanding of formal elements and structure, we should not become so carried away that we neglect the roles history and cultural circumstances can play in shaping a piece. Likewise, as Edward Hirsch suggests, it is also important to recognize the contribution that you make as a reader to the construction of a text’s meaning. Consider the poem “Dulce et Decorum est” by Wilfred Owen. The content of the text is moving enough, yet the added emotional weight of understanding the poem’s context — the mass casualties in Europe during World War I — lends a potent specificity to the imagery in Owen’s poem. The poem’s effect is made all the more palpable by the knowledge that he was killed in action one week before the Armistice that ended the fighting in Western Europe. With this historical context in mind, it might be possible then to consider what your own experience or views on war might be. The context of a text can play a major role in what gives it a lasting literary value. However, when a powerful historical context meets masterful formal execution, it can be tempting to assume everything in the piece is a direct line to the author’s heart and mind. But when analyzing a poem or story, the speaker, the narrator, the “I” voice, should not be conflated with the author of the poem. In the written analysis, we refer to “the author” when speaking of his or her craftsmanship and authorial choices, as in “the author repeats the symbol of the bird at the beginning and the end of the poem.” We use “the speaker” when discussing the point-of-view of the narrator of the story, or the “I” speaking in the poem, as in “the speaker longs to be free” or “the speaker bemoans the impending loss of her child.” In our analysis we can suggest that “the poet” is closely aligned with “the speaker,” but we should not assume they are one and the same.

Preparing for Research — Knowing Your Thesis

If we truly are engaged in writing and research as a process, then finding the thesis or purpose statement that will ground and drive your analysis essay will not be instant. Drafting different versions of what will be your thesis is advisable. Consider the preparation that would occur for other things you would place before an audience, like a business proposal or an invitation to a party; some refinement would be required.

For example, if your goal was to write an analysis of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn, it is likely that several ideas for a thesis statement would come to mind.

The friendship between Huck and Jim reveals Twain’s commentary on the moral dilemma of slavery.

This is a fair enough focus. It is analytical; it does more than summarize. It places a proposition before the reader and upon consideration of that proposition would lead to a richer understanding of the novel. However, slight alterations in this thesis statement may offer improvements or interesting variations. For instance, an emphasis on the form could add to the analysis of the content of the novel.

The friendship of Huck and Jim reveals Twain’s commentary on the moral dilemma of slavery as revealed through the use of dialogue and interior monologue.

A further refinement might manage to incorporate form, content, AND context. Notice that a fully developed thesis may well require more than one long, run-on sentence.

Mark Twain encourages the reading audience of his day to question the moral dilemma of slavery through his portrayal of the friendship between Huck and Jim. By revealing differing social perspectives and moral positions through the dialogue between the characters and the interior monologues of Huck, Twain allows his readers to have multiple opinions while nudging their sympathies toward a critique of slavery.

The advantage of establishing your thesis before embarking upon outside research is that you are more likely to be focused on the kinds of sources that will be most useful and less likely to be overwhelmed or sidetracked by tangential information. You may want to look up general information, such as confirming historical dates or clarifying the use of certain vocabulary, but entering the process of looking for quality sources without a clear sense of the thesis you intend to place at the center of your analysis may muddle your thinking. Certainly, as you continue your research and draft and revise your essay, your thesis, and/or your supporting ideas may shift somewhat. That is a natural part of the writing process, but that kind of adjustment in thinking deepens or refines your analysis.

Suggested Assignment: Time to Write

Purpose: This assignment will demonstrate the understanding of how to respond to a piece of literature you have read by evaluating it and making a claim or observation about the way it relates to a larger issue or idea.

Task: This assignment frames a single short story in which the student analyzes the significance of the elements in the text.

Write a Literary Analysis. Concentrating on the literary elements of the text, write a short essay in which you analyze the significance of specific literary elements with evidence from the text itself and from outside sources.

Key Features of a Literary Analysis:

-

Introduce an interpretation of the literary work

-

Present specific questions or ideas that need a response

-

Present a clear argument in your thesis

-

Use quotes from the literary text

-

Explain how the quotes support your thesis

-

If it is a long text, you may need to focus on a particular section such as a chapter

Key Grading Considerations

-

Content

-

A clear focus on literary elements

-

Supporting points are credible, clear, and explained

-

3 solid, supporting points minimum

-

3 sources, used in an appropriate manner

-

All information is clear, appropriate, and correct.

-

-

Key Features of Analysis are included

-

Organization

-

Transitions

-

Argumentative Thesis Statement

-

Topic Sentences

-

Clear introduction, body, and conclusion

-

-

Comprehension of the literary text

-

Language Use, Mechanics & Organization

-

Correct, appropriate, and varied integration of textual examples, including in-text citations

-

Limited errors in spelling, grammar, word order, word usage, sentence structure, and punctuation

-

Good use of academic English

-

Demonstrates cohesion and flow

-

-

Fully in MLA Format

-

Paper Format

-

In-text Citations

-

Citation Format

-

Attributions:

-

“Introduction to Literature” by Dr. Karen Palmer adapted from Literature, the Humanities, and Humanity by Theodore L. Steinberg and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

-

“Approaches to Literary Analysis” by FSCJ found in Literature for the Humanities by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC-BY 4.0

-

Original Content “Time to Write” by Christine Jones is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication