As you search for sources on your topic, it’s important to make a plan for that research process. You should develop a research strategy that fits within your assignment expectations and considers your source requirements. Your research strategy should be based on the research requirements your professor provides. Some formal research essays should include peer-reviewed journal articles only; however, there are some research papers that may allow you to use a wider variety of sources, including sources from the World Wide Web.

If your professor has not established research requirements for your assignment, it’s a good idea to ask. Although general internet searching is great for generating ideas, you may not be able to use internet sources for all research projects.

Databases can help you to identify and secure information across a range of subjects. Such information might include a chapter in a book, an article in a journal, a report, or a government document. Databases are a researcher’s best friend, but it can take a little time to get used to searching for sources in your library’s databases. Be prepared to spend some time getting comfortable with the databases you’re working in, and be prepared to ask questions of your professor and librarians if you feel stuck.

Databases can help you to identify and secure information across a range of subjects. Such information might include a chapter in a book, an article in a journal, a report, or a government document. Databases are a researcher’s best friend, but it can take a little time to get used to searching for sources in your library’s databases. Be prepared to spend some time getting comfortable with the databases you’re working in, and be prepared to ask questions of your professor and librarians if you feel stuck.

Becoming adept at searching online databases will give you the confidence and skills you need to gather the best sources for your project.

Your online college library can help you learn how to select search terms and understand which database would be the most appropriate for your project. College libraries will require login information from students in order to access database resources.

Web research can be an important part of your research process. However, be careful that you use only the highest quality sources that are returned on your general web search. Your paper is only as good as the sources you use within it, so if you use sources that are not written by experts in their field, you may be including misinformed or incorrect information in your paper.

As a general rule, one site to avoid is Wikipedia, which is not considered a quality source for academic writing. While this site is fine for looking up information in a casual way and gaining a better understanding of a subject, it is not recommended for academic writing since information can sometimes be incorrect since the content is user-generated, rather than peer-reviewed and written by experts; peer-reviewed and works written by experts can be found in academic journals, news articles, magazines, or published books. It is also considered more of a “general knowledge” source, and academic writing favors sources with more specific information.

Still, when you are researching on the web, search engines are effective tools for locating web pages relevant to your research, and they can save you time and frustration. However, for searches to yield the best results, you need a strategy and some basic knowledge of how search engines work. Without a clear search strategy, using a search engine is like wandering aimlessly in a field of corn looking for the perfect ear.

In the videocast below, you’ll see our student writer discuss her research strategy and share some of the results of her work researching her question.

As you gather sources for your research, you’ll need to know how to assess the validity and reliability of the materials you find.

Keep in mind that the sources you find have all been put out there by groups, organizations, corporations, or individuals who have some motivation for getting this information to you. To be a good researcher, you need to learn how to assess the materials you find and determine their reliability—before deciding if you want to use them and, if so, how you want to use them.

Whether you are examining the material in books, journals, magazines, newspapers, or websites, you want to consider several issues before deciding if and how to use the material you have found.

- Suitability

- Authorship and Authority

- Documentation

- Timeliness

Does the source fit your needs and purpose?

Does the source fit your needs and purpose?

Before you start amassing large amounts of research materials, think about the types of materials you will need to meet the specific requirements of your project.

Overview Materials

Encyclopedias, general interest magazines (Time, Newsweek online), or online general news sites (CNN, MSNBC) are good places to begin your research to get an overview of your topic and the big questions associated with your particular project. But once you get to the paper itself, you may not want to use these for your main sources.

Focused Lay Materials

For a college-level research paper, you need to look for books, journal articles, and websites that are put out by organizations that do in-depth work for the general public on issues related to your topic. For example, an article on the melting of the polar icecaps in Time magazine offers you an overview of the issue. But such articles are generally written by non-scientists for a non-scientific audience that wants a general—not an in-depth—understanding of the issue. Although you’ll want to start with overview materials to give yourself a broad-stroke understanding of your topic, you’ll soon need to move to journals and websites in the field. For example, instead of looking at online stories on the icecaps from CNN, you should look at the materials at the website for the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) or reports found at the website for the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). You also should look at some of the recent reports on the polar icecaps in Scientific American or The Ecologist.

Specialists’ Materials

If you already have a strong background in your topic area, you could venture into specialists’ books, journals, and websites. For example, only someone with a strong background in the field would be able to read and understand the papers published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences or the Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. Sources such as these are suitable for more advanced research paper assignments in upper-level courses, but you may encounter source requirements like these in freshman writing courses.

When you consider the quality of your sources, you should also consider the authorship and authority of your sources. Who wrote the material? Is that person or organization credible? The following information will provide you with more details on authorship and authority to help you make good decisions about your sources.

Publisher-Provided Biographical Information

Often, books and scholarly journals will have a short biography of the author, outlining her or his credentials: education, publications, and experience in the field.

Look the biography over. Does the material there seem to suggest this writer has in-depth knowledge on the topic? What educational credentials does the writer have? If the writer is a trained economist but is writing on scientific matters, you need to keep that in mind as you look at her or his arguments. If the writer is associated with a specific conservative or liberal think tank, be aware that the arguments presented will probably reflect the ideology of that organization.

An ideological agenda does not mean that you have to avoid material. You simply need to read it with an awareness that the writer is writing from a specific point of view.

Minimal qualifications or qualifications that seem unrelated to the topic are a warning sign to you that you might want to reconsider using the material.

Outside Biographical Information

If no biography is attached to the work, an advanced search on Google or another search engine can be very helpful. You might also check hard copy or online sources such as Contemporary Authors, Book Review Index, or Biography index.

Many authors also have their own websites, listing information about their educational background, current and past research, and experience.

If you can find no or little information about a writer, be careful about using her or his material. You may want to consider replacing it altogether with a different source where the credentials of the writer are more readily available.

No Author Listed

While you want to be careful of sources without authors, that doesn’t mean you can’t use them. Often, websites won’t list an author. In that case, you need to evaluate the sponsoring organization. Look for the following information:

- Does the home page offer information about the organization?

- Is there a mission statement?

- Does the site offer any indication that the material on the webpage has been reviewed or checked by experts, often called a “peer-review process”?

- Does the site provide a link with an address, phone, and email?

Yes — If you find only some of the points from the bulleted list, try filling in the blanks with an internet search on the organization. Often, an encyclopedia — online or hard copy — provides background information on an organization. Try to find out a little bit about who funds it, who its audience is, and what its objectives are.

Again, discovering that an organization has specific ideological ties does not mean that you need to discard the material you have found there. You simply need to use it carefully and balance it with material from other sources.

No — If the answer to all of the bulleted questions is “no,” be careful!

A site that provides no information about its sponsors is a site that you should avoid using for your paper.

If no one is willing to put her or his name on the site and accept responsibility for the information, do you think you should trust that information for your research? Definitely not.

Where does the book/article/website get its information?

Look for a bibliography and/or footnotes. In a piece of writing that is making a case using data, historical or scientific references, or appeals to outside sources of any kind, those sources should be thoroughly documented. The writer should give you enough information to go and find those sources yourself and double-check that the materials are used accurately and fairly by the author.

Popular news magazines, such as Time or Newsweek online, will generally not have formal bibliographies or footnotes with their articles. The writers of these articles will usually identify their sources within their texts, referring to studies, officials, or other texts. These types of articles, though not considered academic, may be acceptable for some undergraduate college-level research papers. Check with your instructor to make sure that these types of materials are allowed as sources in your paper.

Examine the sources used by the author. Is the author depending heavily on just one or two sources for his or her entire argument? That’s a red flag for you. Is the author relying heavily on anonymous sources? There’s another red flag. Are the sources outdated? Another red flag.

If references to outside materials are missing or scant, you should treat this piece of writing with skepticism. Consider finding an alternative source with better documentation.

Is the material up-to-date?

The best research draws on the most current work in the field. That said, depending on the discipline, some work has a longer shelf life than others. For example, important articles in literature, art, and music often tend to be considered current for years, or even decades, after publication. Articles in the physical sciences, however, are usually considered outdated within a year or two (or even sooner) after publication.

In choosing your materials, you need to think about the argument you’re making and the field (discipline) within which you’re making it.

For example, if you’re arguing that climate change is indeed anthropogenic (human-caused), do you want to use articles published more than four or five years ago? No. Because science has evolved very rapidly on that question, you need to depend most heavily on research published within the last year or two.

However, suppose you’re arguing that blues music evolved from the field songs of American slaves. In this case, you should not only look at recent writing on the topic (within the last five years), but also look at historical assessments of the relationship between blues and slavery from previous decades.

Timeliness and Websites

Scrutinize websites, in particular, for dates of posting or for the last time the site was updated. Some sites have been left up for months or years without the site’s owner returning to update or monitor the site. If sites appear to have no regular oversight, you should look for alternative materials for your paper.

Friebolin, C. (2012, July 24). Can’t lie on the internet [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/bufTna0WArc

You may have seen the commercial above making a point about how you have to be careful of what you find on the internet. This is true in life and in your efforts to find quality sources for academic papers.

The internet is particularly challenging because anyone can really post anything they want on the internet. At the same time, there are some really quality sources out there, such as online journals.

The important thing is to use skepticism, use the guidelines you have read about in this section of Research, and be sure to ask your professor if general web sources are even allowed. Sometimes, in an effort to have students steer clear of inaccurate information, professors will forbid general web sources for a paper, but this is not always the case. If you are allowed to go to the web to locate sources, just remember to check for suitability, credibility, and timeliness using the guidelines presented here.

Using an Evaluation Checklist will also give you some good guidelines to remember, no matter where you found your source.

Now that you have an understanding of some effective ways to evaluate sources, it’s time to check in with our student writer. In this videocast, you’ll see our student writer evaluate one of her sources for relevance or suitability, credibility, and timeliness.

When writing an argumentative essay, you’ll definitely want to locate quality sources to support your claims, and you have a lot of options for sources. You can look for support for your argument in journal articles, magazine articles, documentaries, and more. You may even be allowed to use personal experience and observations, but this isn’t always the case. No matter what, you’ll want logical, clear, and reasonable evidence that helps you support your claims and convince your audience.

When writing an argumentative essay, you’ll definitely want to locate quality sources to support your claims, and you have a lot of options for sources. You can look for support for your argument in journal articles, magazine articles, documentaries, and more. You may even be allowed to use personal experience and observations, but this isn’t always the case. No matter what, you’ll want logical, clear, and reasonable evidence that helps you support your claims and convince your audience.

It’s important to review the logical fallacies before you develop evidence for your claims. If you’re using personal experience, you have to be careful that you don’t make claims that are too broad-based on limited experiences.

The following pages provide you with information on the types of sources you may be able to include, how to decide if your sources are credible, and how to make good decisions about using your sources.

Chances are, if you have chosen an issue to write about for your argumentative essay, you have chosen a topic that means something to you. With this in mind, you may have had a personal experience related to the issue that you would like to share with your audience.

Chances are, if you have chosen an issue to write about for your argumentative essay, you have chosen a topic that means something to you. With this in mind, you may have had a personal experience related to the issue that you would like to share with your audience.

This isn’t always going to be allowed in an argumentative essay, as some professors will want you to focus more on outside sources. However, many times, you’ll be allowed to present personal experience. Just be sure to check with your professor.

If you do have personal experiences to share, you have to make sure you use those experiences carefully. After all, you want your evidence to build your ethos, not take away from it. If you have witnessed examples that are relevant, you can share those as long as you make sure you don’t make claims that are too big based on those experiences.

A student is writing an argumentative paper on welfare reform, arguing that there are too many abuses of the system. The student gives an example of a cousin who abuses the system and makes a claim that this is evidence that abuse of the system is widespread.

A student is writing an argumentative paper on welfare reform and has statistical evidence to support claims that the system is not working well. Instead of using the personal experience of a cousin who abuses the system as key evidence, the student shares data and then presents the personal experience as an example that some people may witness.

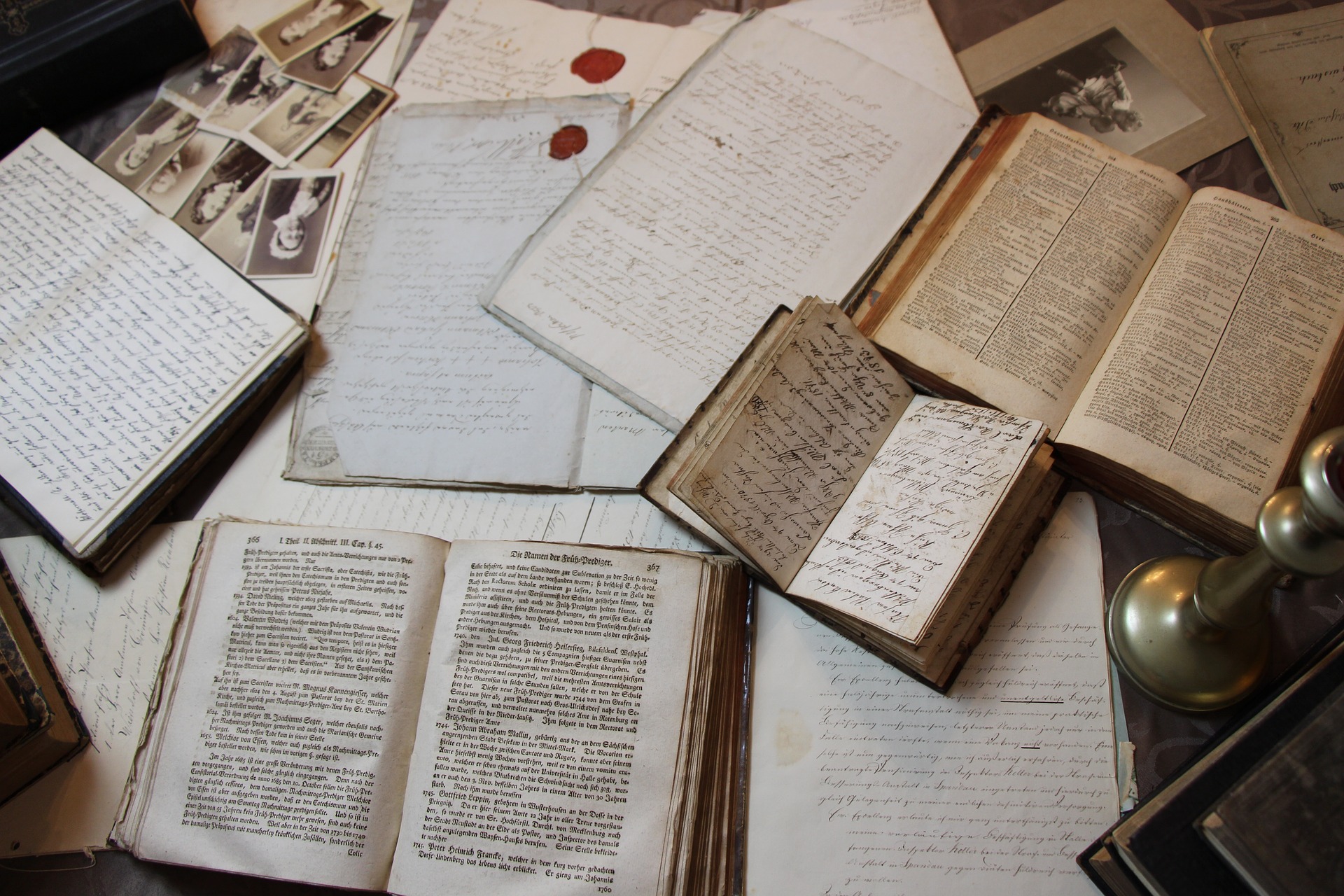

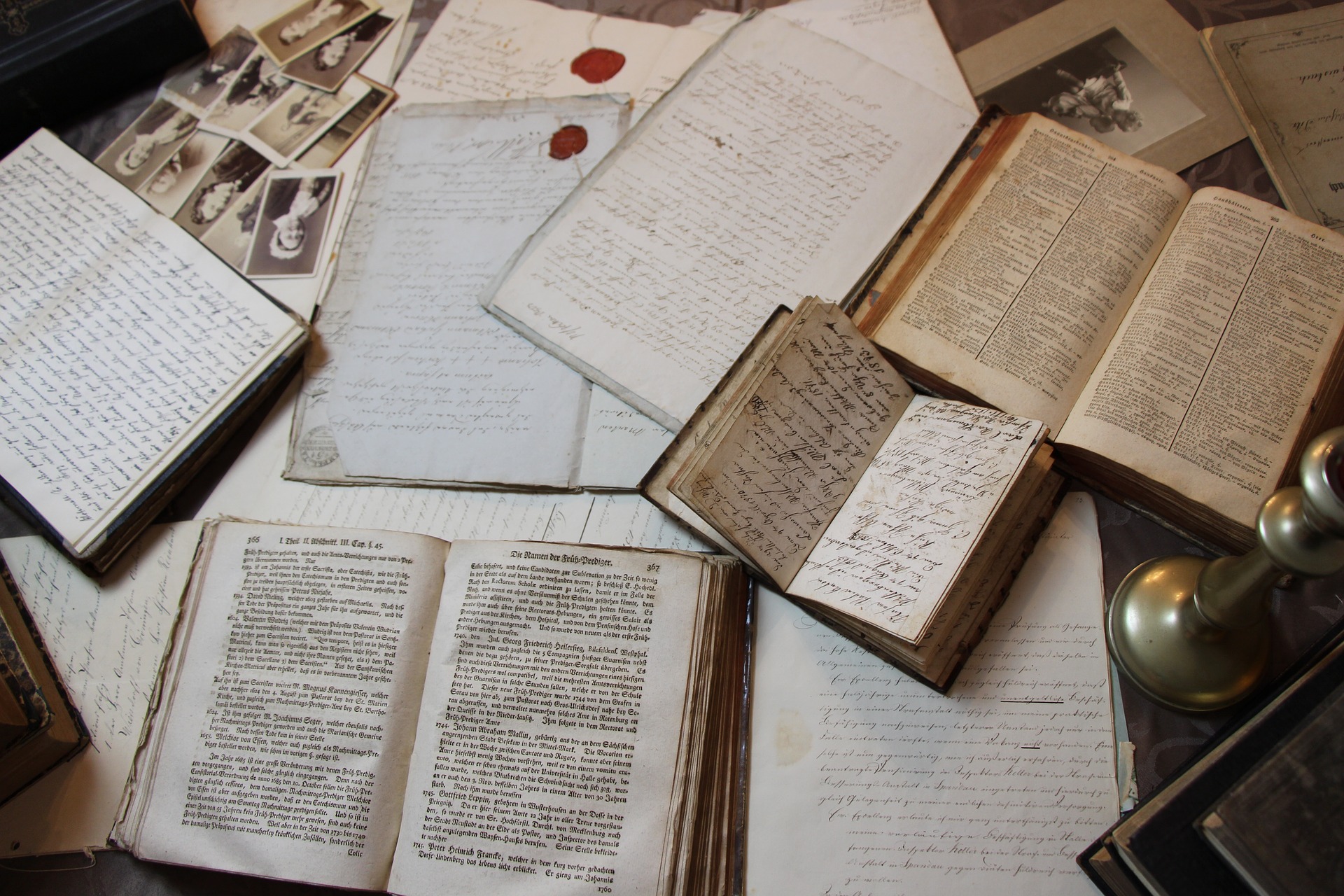

When you use source material outside of your own experience, you’re using either primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are sources that were created or written during the time period in which they reference and can include things like diaries, letters, films, interviews, and even results from research studies. Secondary sources are sources that analyze primary sources in some way and include things like magazine and journal articles that analyze study results, literature, interviews, etc.

When you use source material outside of your own experience, you’re using either primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are sources that were created or written during the time period in which they reference and can include things like diaries, letters, films, interviews, and even results from research studies. Secondary sources are sources that analyze primary sources in some way and include things like magazine and journal articles that analyze study results, literature, interviews, etc.

Sometimes, you’ll be conducting original research as you work to develop your argument, and your professor may encourage you to do things like conduct interviews or locate original documents. Personal interviews can be excellent sources that can help you build your ethos, pathos, and logos in your essay.

When conducting an interview for your research, it’s important to be prepared in order to make the most of your time with the person you are interviewing.

The following tips will help you get the most out of your interview:

- Prepare questions you want to ask in advance.

- Be prepared with some follow-up questions, just in case the questions you have prepared don’t get the interviewee talking as you had hoped.

- Have a recording device handy. It’s a good idea to record your interview if your interviewee is okay with it.

- If you can’t record the interview, come prepared to take good notes.

- Record the date of your interview, as you will need this for documentation.

- Obtain contact information for your interviewee in case you have follow-up questions later.

- Be polite and appreciative to your interviewee, as you will want the experience to be a positive one all the way around.

When you’re searching for secondary source material to support your claims, you want to keep some basic ideas in mind:

- Your source material should be relevant to your content.

- Your source material should be credible, as you want your sources to help you build your ethos.

- Your source material should be current enough to feel relevant to your audience.

Before you make your final decisions about the sources you’ll use in your argumentative essay, it’s important to review the following pages and take advantage of the helpful source credibility checklist.

Just as with any type of essay, when you write an argumentative essay, you want to integrate your sources effectively. This means you want to think about the different ways you integrate your sources (paraphrasing, summarizing, quoting) and how you can make sure your audience knows your source information is credible and relevant. this helpful checklist on source integration can help you remember some of the key best practices when it comes to getting the most out of your source material in your argumentative essay.

These key lessons on source integration in Research are relevant.

- Summarizing

- Paraphrasing

- Quoting

- Signal Phrases

Your authority as a scholar will be enhanced when you demonstrate your ability to use and integrate outside sources in a fair and attentive manner. By doing so, you help to demonstrate that you have carefully read and considered the material on your topic. Your reader sees not only your ideas alone but also your points contextualized by the conversations of others. In this way, you establish yourself as one of the members of the community of scholars engaged with the same idea.

When it’s time to draft your essay and bring your content together for your audience, you will be working to build strong paragraphs. Your paragraphs in a research paper will focus on presenting the information you found in your source material and commenting on or analyzing that information. It’s not enough to simply present the information in your body paragraphs and move on. You want to give that information a purpose and connect it to your main idea or thesis statement.

Your body paragraphs in a research paper will include summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting your source material, but you may be wondering if there is an effective way to organize this information.

Duke University coined a term called the “MEAL Plan” that provides an effective structure for paragraphs in an academic research paper. Select the pluses to learn what each letter stands for.

One way to integrate your source information is through the summary. Summaries are generally used to restate the main ideas of a text in your own words. They are usually substantially shorter than the original text because they don’t include supporting material. Instead, they include overarching ideas of an article, a page, or a paragraph.

Some summaries, such as the ones that accompany annotated bibliographies, are very short, just a sentence or two. Others are much longer, though summaries are always much shorter than the text being summarized in the first place.

Summaries of different lengths are useful in research writing because you often need to provide your readers with an explanation of the text you are discussing. This is especially true when you are going to quote or paraphrase from a source.

Of course, the first step in writing a good summary is to do a thorough reading of the text you are going to summarize in the first place. Beyond that important start, there are a few basic guidelines you should follow when you write summary material:

- Stay “neutral” in your summarizing. Summaries provide “just the facts” and are not the place where you offer your opinions about the text you are summarizing. Save your opinions and evaluation of the evidence you are summarizing for other parts of your writing.

- Don’t quote from what you are summarizing. Summaries will be more useful to you and your colleagues if you write them in your own words.

- Don’t “cut and paste” from database abstracts. Many of the periodical indexes that are available as part of your library’s computer system include abstracts of articles. Do no “cut” this abstract material and then “paste” it into your own annotated bibliography. For one thing, this is plagiarism. Second, “cutting and pasting” from the abstract defeats one of the purposes of writing summaries and creating an annotated bibliography in the first place, which is to help you understand and explain your research.

For example, in the first chapter of his 1854 book, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, Henry David Thoreau wrote the following:

Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them. Their fingers, from excessive toil, are too clumsy and tremble too much for that. Actually, the laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market. He has no time to be anything but a machine. How can he remember well his ignorance—which his growth requires—who has so often to use his knowledge? We should feed and clothe him gratuitously sometimes, and recruit him with our cordials, before we judge of him. The finest qualities of our nature, like the bloom on fruits, can be preserved only by the most delicate handling. Yet we do not treat ourselves nor one another thus tenderly.

What is the main idea in the passage above? The following is one way the passage might be summarized.

In his 1854 text, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, Henry David Thoreau suggests that the human fixation on work and labor desensitizes man to the world around him, to the needs of his own intellectual growth, and to the complexity and frailty of his fellow humans.

NOTE: The summary accomplishes two goals:

- It contextualizes the information (who said it, when, and where).

- It lists the main ideas of the passage without using quotations or citing specific supporting points of the passage.

You should use summaries of your source materials when you need to capture main ideas to support a point you are making.

Test Your Understanding of Summarizing:

This article contains the following quotation:

“In a study of Australians with psychiatric service dogs, the participants reported their dogs “making” them leave the house or get out of bed, “reminding” them about medication, “sensing” their emotions and nudging them to bring them back to the present or blocking contact with a person they feared. For almost half the participants, their dog led them to need less mental health care, because they were hospitalized less often, made fewer suicide attempts, or needed less medication (Ehrenfeld).”

How to Quote and Paraphrase: An Overview

Writers quote and paraphrase from research in order to support their points and to persuade their readers. A quote or a paraphrase from a piece of evidence in support of a point answers the reader’s question, “says who?”

This is especially true in academic writing since scholarly readers are most persuaded by effective research and evidence. For example, readers of an article about a new cancer medication published in a medical journal will be most interested in the scholar’s research and statistics that demonstrate the effectiveness of the treatment. Conversely, they will not be as persuaded by emotional stories from individual patients about how a new cancer medication improved the quality of their lives. While this appeal to emotion can be effective and is common in popular sources, these individual anecdotes do not carry the same sort of “scholarly” or scientific value as well-reasoned research and evidence.

Of course, your instructor is not expecting you to be an expert on the topic of your research paper. While you might conduct some primary research, it’s a good bet that you’ll be relying on secondary sources such as books, articles, and Web sites to inform and persuade your readers. You’ll present this research to your readers in the form of quotes and paraphrases.

A “quote” is a direct restatement of the exact words from the original source. The general rule of thumb is any time you use three or more words as they appeared in the original source, you should treat it as a quote. A “paraphrase” is a restatement of the information or point of the original source in your own words.

While quotes and paraphrases are different and should be used in different ways in your research writing (as the examples in this section suggest), they do have a number of things in common. Both quotes and paraphrases should:

- be “introduced” to the reader, particularly the first time you mention a source;

- include an explanation of the evidence which explains to the reader why you think the evidence is important, especially if it is not apparent from the context of the quote or paraphrase; and

- include a proper citation of the source.

When you want to use specific materials from an argument to support a point you are making in your paper but want to avoid too many quotes, you should paraphrase.

What is a paraphrase?

Paraphrases are generally as long, and sometimes longer than the original text. In a paraphrase, you use your own words to explain the specific points another writer has made. If the original text refers to an idea or term discussed earlier in the text, your paraphrase may also need to explain or define that idea. You may also need to interpret specific terms made by the writer in the original text.

Be careful not to add information or commentary that isn’t part of the original passage in the midst of your paraphrase. You don’t want to add to or take away from the meaning of the passage you are paraphrasing. Save your comments and analysis until after you have finished your paraphrased and cited it appropriately.

What does paraphrasing look like?

Paraphrases should begin by making it clear that the information to come is from your source. If you are using APA format, a year citation should follow your mention of the author.

For example, using the Thoreau passage as an example, you might begin a paraphrase like this:

Even though Thoreau (1854) praised the virtues of intellectual life, he did not consider….

Paraphrases may sometimes include brief quotations, but most of the paraphrase should be in your own words.

What might a paraphrase of this passage from Thoreau look like?

“Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them. Their fingers, from excessive toil, are too clumsy and tremble too much for that. Actually, the laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market.”

In his text, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, Henry David Thoreau (1854) points to the incongruity of free men becoming enslaved and limited by constant labor and worry. Using the metaphor of fruit to represent the pleasures of a thoughtful life, Thoreau suggests that men have become so traumatized by constant labor that their hands—as representative of their minds—have become unable to pick the fruits available to a less burdened life even when that fruit becomes available to them (p. 110).

Note that the passage above is almost exactly the same length as the original. It’s also important to note that the paraphrased passage has a different structure and significant changes in wording. The main ideas are the same, but the student has paraphrased effectively by putting the information into their own words.

What are the benefits of paraphrasing?

The paraphrase accomplishes three goals:

- Like the summary, it contextualizes the information (who said it, when, and where).

- It restates all the supporting points used by Thoreau to develop the idea that man is hurt by focusing too much on labor.

- The writer uses their own words for most of the paraphrase, allowing the writer to maintain a strong voice while sharing important information from the source.

Paraphrasing is likely the most common way you will integrate your source information. Quoting should be minimal in most research papers. Paraphrasing allows you to integrate sources without losing your voice as a writer to those sources. Paraphrasing can be tricky, however. You really have to make changes to the wording. Changing a few words here and there doesn’t count as a paraphrase, and, if you don’t quote those words, can get you into trouble with plagiarism.

As noted, when you paraphrase, you have to do more than change the words from the original passage. You have to also change the sentence structure. Sometimes, students will struggle with paraphrasing because they have an urge to simply use the same basic sentence or sentences and replace the original words with synomyms. This is not a method that works for effective paraphrasing.

Let’s see what that looks like. Here’s an original quote from an article about a new video game based on Thoreau’s famous work, Walden.

“The digital Walden Pond will showcase a first-person point-of-view where you can wander through the lush New England foliage, stop to examine a bush and pick some fruit, cast a fishing rod, return to a spartan cabin modeled after Thoreau’s and just roam around the woods, grappling with life’s unknowable questions.”

According to Hayden (2012), the Walden Pond game will offer a first-person view in which the play can meander within the New England trees and wilderness, pause to study foliage or grab some food, go fishing, return home to a small cabin based on Thoreau’s cabin, and just venture around in the woods, pondering important questions of life (para. 3).

Explanation

Here, you can see that the “paraphrase” follows the exact same structure as the orignal passage. Even though the wording has been changed, this would be considered a form of plagiarism by some because the sentence structure has been copied, taking this beyond just sharing the ideas of the passage. Let’s take a look at a better paraphrase of the passage.

According to Hayden (2012), the upcoming video game Walden Pond is a first-person game that simulates the life and experiences of Thoreau when he lived at Walden Pond. Based upon Thoreau’s famous work, Walden, the game allows players to experience life in the New England woods, providing opportunities for players to fish, gather food, live in a cabin, and contemplate life, all within a digital world (para. 3).

Explanation

In this paraphrase, the student has captured the main idea of the passage but changed the sentence structure and the wording. The student has added some context, which is often helpful in a paraphrase, by providing some background for the game.

You will now have the chance to practice your ability to recognize an effective paraphrase in the Paraphrasing Activity.

Test Your Understanding of Paraphrasing:

This article contains the following quotation:

“Student development of 21st-century skills is greatly needed to promote workforce preparedness and long-term success of the U.S. economy. To add to the discussion on which skills are of the greatest importance for students to develop before entering the workforce, this study investigated skill demand based on direct communication from employers to potential employees via job advertisements. The four most in-demand 21st-century skills found across roughly 142,000 job advertisements were oral and written communication, collaboration, and problem-solving (Rios et al. 80).”

Here is another article to view.

Article: Animal Testing: Is Animal Testing Morally Justified?, Issues & Controversies, 2020

Example: From the article ” Human beings have long used animals as test subjects for a variety of purposes. Every year, tens of millions of animals are used in laboratory settings to gauge the toxicity of newly developed chemicals. If deemed safe, these chemicals find their way into a wide range of consumer goods including cosmetics, household cleaners, pesticides, shampoos, and sunscreens (“Animal Testing”).

Quotations are another way to integrate source information into your paragraphs, but you should use them sparingly.

Quotations are another way to integrate source information into your paragraphs, but you should use them sparingly.

How do you know when you should use quotations in your essay? Essentially, quotations should function to support, comment on, or give an example of a point you are making in your own words. And, of course, you should keep in mind that quotes should be kept to a minimum. A good “rule” to remember is that you only want to use a quote when it’s absolutely necessary, when your source puts something in a way that just needs to be put that way or when you need a quote from an expert to support a point you have already made.

You should also remember that you don’t want to use quotations to make your point for you. Readers should be able to skip the quotations in your paper and still understand all your main points. This means, after each quote, you have to provide an analysis for that quote. This works well if you follow the MEAL Plan. The idea is to help your audience gather the meaning from the quote you want them to gather. It’s your job as a writer to make the quote meaningful for your audience.

Integrating quotations smoothly and effectively is one sign of a truly polished writer. Well-chosen and well-integrated quotations add strength to an argument. But many new writers do not know how to do the choosing and integrating effectively. The following guidelines will help make your quotations operate not as stumbling blocks to a reader, but as smooth and easy stepping-stones through the pathways of your paper.

When to Use Quotes

- When the wording is so specific to the meaning that you cannot change the wording without changing the meaning.

- When the wording is poetic or unique, and you want to maintain that unique quality of wording as part of the point you are making. This guideline may also apply when the wording is highly technically-specific.

- When you are doing a critical/literary analysis of a text.

- When you want to maintain the specific authority of the words of a well-known or highly-reputable author in order to add to the credibility of your own argument.

- In most other cases, you should use your own words, a summary, or a paraphrase of your source, to make your point.

Although you generally want to avoid using too many short quotes when you write, there are times when you need to quote a word or a phrase as a part of your own sentence. Short phrases and single words should work smoothly with the structure of your own sentence. Look, for example, at the way the brief passages from Thoreau’s Walden flow into the surrounding sentence:

The demands of a market economy, in fact, would penalize a man who chose to give precedence to relationships and “true integrity” over labor: an over-emphasis on work leaves a man dehumanized and with “no time to be anything but a machine” (Thoreau 21).

Usually, when you find it necessary to quote, you’ll be using a full sentence or two from a text as a quotation. In addition to making sure the quote is necessary and meaningful, be sure to make the quote works with your own writing. Your quote must work well in terms of the flow of your writing and in terms of the content. You don’t want to simply drop in a quote without connecting it to the surrounding text. Look, for example, at the following:

Thoreau argues that a market economy penalizes a man who chooses to give precedence to parts of his life other than work. “Actually, the laboring man has no leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market” (21).

The quotation, “Actually, the laboring man…” isn’t connected to the previous sentence, and there’s no analysis following the quote to help readers understand its meaning and purpose.

Here are some good content guidelines to follow when using sentences as quotations:

- Be sure to give your quote some set up and context. You will learn more about doing this in the next lesson on signal phrases.

- Don’t forget to provide a proper citation for your quote. Find out if you need to follow MLA, APA, or another documentation style’s guidelines.

- After your quote, you’ll need anywhere from a sentence to several sentences to provide commentary or analysis on the quote. How much you write here will depend upon the situation and the quote, but you always need something following a quote, as you want to control how your reader understands the quote.

And, in addition to those content guidelines, here are some good guidelines when thinking about your sentence structure as you set up your quote:

- When the introductory text is a complete sentence, connect it to the quotation with a colon.

- When the introductory text is an introductory phrase (rather than a complete sentence), connect it to the quotation with a comma.

- When the introductory text works directly with the flow of the sentence that follows, use no punctuation at all.

Long quotations should be kept to a minimum in your essay. Mrs. Jones recommends no more than one long quote per five (5) pages of essay. So, in a ten (10) page paper, you shouldn’t have more than 2 long quotes. Additionally, you should only use those parts of the long quotation that you really need. If a passage has a middle section that doesn’t relate to the point you are making, drop it out and replace it with an ellipsis (…) to indicate that you have left out part of the original text.

Set up long quotations in blocks; these are generally called block quotations. Block quotations are most often used if the passage takes up more than four typed lines in your paper. Indentation and spacing guidelines vary depending on the formatting style you are using (APA, MLA, Chicago, or other). English 101 for Mrs. Jones requires MLA style.

Leave the quotation marks off of a block quotation. The indentation itself is the visual indicator to the reader that the text is a quote. Block quotations usually are introduced with a full sentence that summarizes the main point of the quotation. This introductory sentence should be followed by a colon, as in the example below.

Henry David Thoreau argued in Walden that men who are over-occupied with labor run the risk of becoming dehumanized. They must be granted the time to learn about, and address, their own shortcomings in order to fully mature as humans:

He has not time to be anything but a machine. How can he remember well his ignorance–which his growth requires–who has so often to use his knowledge? We should feed and clothe him gratuitously sometimes, and recruit him with our cordials, before we judge of him. The finest qualities of our nature, like the bloom on fruits, can be preserved only by the most delicate handling. (23)

It’s important to remember that longer quotes should be set up and followed by commentary and analysis, just like shorter quotes. For long quotes, you should follow the same guidelines related to content that you follow for shorter quotes. It’s important to always think rhetorically about your writing, even when you’re quoting. So, if you use a long quote in your essay, be sure to provide some analysis after that quote to let your audience know why the quote is there and why it’s important. Otherwise, long quotes can look and feel like “filler” to your audience.

Block Quotations (4 Lines or More)

When quoting works longer than 4 lines, use a block quote format:

- Indent 1/2 inch from the left margin

- Do not use quotation marks

- Include in-text citation at end of quote

- Introduce block quote with a complete sentence followed by a colon

There are several important questions about bullying that all educational leadership should consider:

Is bullying minimized as a “normal rite of childhood,” or is it recognized as the harmful peer abuse that it is? Do leaders understand that uninterrupted, severe bullying can confer lifelong negative consequences on targets of bullies, bullies, and witnesses? Are school leaders committed to promoting all children’s positive psychological health, or do they over-rely on punishing misbehavior? Can they discern between typical developmental processes that need guidance versus bullying that needs assertive intervention? Are educators empathic to their students, and do they value children’s feelings? (Divecha)

When to Quote, When to Paraphrase

The real “art” to research writing is using quotes and paraphrases from evidence effectively in order to support your point. There are certain “rules,” dictated by the rules of style you are following, such as the ones presented by the MLA. There are certain “guidelines” and suggestions, like the ones I offer in the previous section and the ones you will learn from your teacher and colleagues.

But when all is said and done, the question of when to quote and when to paraphrase depends a great deal on the specific context of the writing and the effect you are trying to achieve. Learning the best times to quote and paraphrase takes practice and experience.

In general, it is best to use a quote when:

- The exact words of your source are important for the point you are trying to make. This is especially true if you are quoting technical language, terms, or very specific word choices. When original writing has striking or memorable author statements, expert opinions.

- You want to highlight your agreement with the author’s words. If you agree with the point the author of the evidence makes and you like their exact words, use them as a quote. When you cannot easily express the same idea in your own words. When using your own words would lessen the impact of the original language.

- You want to highlight your disagreement with the author’s words. In other words, you may sometimes want to use a direct quote to indicate exactly what it is you disagree about. When you plan to argue against a writer’s ideas and want to accurately state them.

In general, it is best to paraphrase when:

- There is no good reason to use a quote to refer to your evidence. If the author’s exact words are not especially important to the point you are trying to make, you are usually better off paraphrasing the evidence.

- You are trying to explain a particular piece of evidence in order to explain or interpret it in more detail. This might be particularly true in writing projects like critiques.

- You need to balance a direct quote in your writing. You need to be careful about directly quoting your research too much because it can sometimes make for awkward and difficult to read prose. So, one of the reasons to use a paraphrase instead of a quote is to create balance within your writing.

Tips for Quoting and Paraphrasing

- Introduce your quotes and paraphrases to your reader, especially on the first reference.

- Explain the significance of the quote or paraphrase it to your reader.

- Cite your quote or paraphrase properly according to the rules of style you are following in your essay.

- Quote when the exact words are important when you want to highlight your agreement or your disagreement.

- Paraphrase when the exact words aren’t important, when you want to explain the point of your evidence, or when you need to balance the direct quotes in your writing.

After completing this activity, you may download or print a completion report that summarizes your results.

In this videocast, you’ll see our student writer examine her rough draft and discuss how she integrated her source material into her paper.

As a part of your argumentative research process, your professor may require an argumentative annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography is a list of potential sources for your paper or project with summaries and evaluations. A traditional annotated bibliography can be found on the Annotated Bibliographies page, but your professor may ask you to take an argumentative angle with your annotated bibliography and focus more attention on evaluating the persuasive elements of the source.

A basic argumentative annotated bibliography will include the following for each entry:

- Reference information following a particular formatting style (APA, MLA, or another)

- A summary of the source’s content

- A thorough evaluation of the argument that includes a focus on rhetorical concepts and terms

- A few sentences on how you will use this source in your paper or project

A sample argumentative annotated bibliography can be found here. In the sample, the different parts of each entry have been noted for you.

After completing this activity, you may download or print a completion report that summarizes your results.

Using Sources Blending Source Material with Your Own Work

When working with sources, many students worry they are simply regurgitating ideas that others formulated. That is why it is important for you to develop your own assertions, organize your findings so that your own ideas are still the thrust of the paper, and take care not to rely too much on any one source, or your paper’s content might be controlled too heavily by that source.

In practical terms, some ways to develop and back up your assertions include:

Blend sources with your assertions. Organize your sources before and as you write so that they blend, even within paragraphs. Your paper—both globally and at the paragraph level—should reveal relationships among your sources, and should also reveal the relationships between your own ideas and those of your sources.

Write an original introduction and conclusion. As much as is practical, make the paper’s introduction and conclusion your own ideas or your own synthesis of the ideas inherent in your research. Use sources minimally in your introduction and conclusion.

Open and close paragraphs with originality. In general, use the openings and closing of your paragraphs to reveal your work—“enclose” your sources among your assertions. At a minimum, create your own topic sentences and wrap-up sentences for paragraphs.

Use transparent rhetorical strategies. When appropriate, outwardly practice such rhetorical strategies as analysis, synthesis, comparison, contrast, summary, description, definition, hierarchical structure, evaluation, hypothesis, generalization, classification, and even narration. Prove to your reader that you are thinking as you write.

Also, you must clarify where your own ideas end and the cited information begins. Part of your job is to help your reader draw the line between these two things, often by the way you create a context for the cited information. A phrase such as “A 1979 study revealed that . . .” is an obvious announcement of citation to come. Another recommended technique is the insertion of the author’s name into the text to announce the beginning of your cited information. You may worry that you are not allowed to give the actual names of sources you have studied in the paper’s text, but just the opposite is true. In fact, the more respectable a source you cite, the more impressed your reader is likely to be with your material while reading. If you note that the source is the NASA Science website or an article by Stephen Jay Gould or a recent edition of The Wall Street Journal right in your text, you offer your readers immediate context without their having to guess or flip to the references page to look up the source.

What follows is an excerpt from a political science paper that clearly and admirably draws the line between writer and cited information:

The above political upheaval illuminates the reasons behind the growing Iranian hatred of foreign interference; as a result of this hatred, three enduring geopolitical patterns have evolved in Iran, as noted by John Limbert. First . . .

Note how the writer begins by redefining her previous paragraph’s topic (political upheaval), then connects this to Iran’s hatred of foreign interference, then suggests a causal relationship and ties her ideas into John Limbert’s analysis—thereby announcing that a synthesis of Limbert’s work is coming. This writer’s work also becomes more credible and meaningful because, right in the text, she announces the name of a person who is a recognized authority in the field. Even in this short excerpt, it is obvious that this writer is using proper citation and backing up her own assertions with confidence and style.

When you use sources to support your claims in your argument, you certainly have a lot of options to consider. Now that you have learned about those options and how you can use those sources to help build a strong argument, it’s time to see source integration in action.

In the following video, a student analyzes another argumentative essay for its use of sources and evidence. Seeing how others use sources to support their arguments can help you when it’s time to develop your own argumentative essay.

I’m too (Insert negative criticism of yourself here). The media says so. is the full essay used in the analysis.

Now that you have learned about the different ways you can use evidence in your argument, it’s a good time to see how our student applies this information to her process.

In this video, our student explores some of the sources she has found, discusses her struggles with contradictions in her research, and explains her plans for using sources in her essay.

Scholarly articles are a little different from other articles and sometimes harder to read. You need to know when you are looking at a journal article.

Click on the plus symbols below to review characteristics of scholarly articles:

It’s your turn now to wrap up your research process and start thinking about how you’ll use sources and which sources you’ll use. Remember, you want to ensure you have quality sources, but those sources can come from your library’s databases, the web, and even interviews if your professor allows for them.

It’s your turn now to wrap up your research process and start thinking about how you’ll use sources and which sources you’ll use. Remember, you want to ensure you have quality sources, but those sources can come from your library’s databases, the web, and even interviews if your professor allows for them.

It’s time to start putting your argument together, and your sources are going to be a key part of that. Before you draft, make some notes about your sources and share them with your professor and classmates for feedback. Do these sources seem credible? Will these sources fit your purpose? How will these sources help your appeals to ethos, pathos, and logos?

You have a lot to think about as you make decisions about your sources, but good planning about your sources will make drafting your essay so much easier.

ATTRIBUTIONS

Databases can help you to identify and secure information across a range of subjects. Such information might include a chapter in a book, an article in a journal, a report, or a government document. Databases are a researcher’s best friend, but it can take a little time to get used to searching for sources in your library’s databases. Be prepared to spend some time getting comfortable with the databases you’re working in, and be prepared to ask questions of your professor and librarians if you feel stuck.

Databases can help you to identify and secure information across a range of subjects. Such information might include a chapter in a book, an article in a journal, a report, or a government document. Databases are a researcher’s best friend, but it can take a little time to get used to searching for sources in your library’s databases. Be prepared to spend some time getting comfortable with the databases you’re working in, and be prepared to ask questions of your professor and librarians if you feel stuck.

Does the source fit your needs and purpose?

Does the source fit your needs and purpose?

When writing an argumentative essay, you’ll definitely want to locate quality sources to support your claims, and you have a lot of options for sources. You can look for support for your argument in journal articles, magazine articles, documentaries, and more. You may even be allowed to use personal experience and observations, but this isn’t always the case. No matter what, you’ll want logical, clear, and reasonable evidence that helps you support your claims and convince your audience.

When writing an argumentative essay, you’ll definitely want to locate quality sources to support your claims, and you have a lot of options for sources. You can look for support for your argument in journal articles, magazine articles, documentaries, and more. You may even be allowed to use personal experience and observations, but this isn’t always the case. No matter what, you’ll want logical, clear, and reasonable evidence that helps you support your claims and convince your audience. Chances are, if you have chosen an issue to write about for your argumentative essay, you have chosen a topic that means something to you. With this in mind, you may have had a personal experience related to the issue that you would like to share with your audience.

Chances are, if you have chosen an issue to write about for your argumentative essay, you have chosen a topic that means something to you. With this in mind, you may have had a personal experience related to the issue that you would like to share with your audience. When you use source material outside of your own experience, you’re using either primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are sources that were created or written during the time period in which they reference and can include things like diaries, letters, films, interviews, and even results from research studies. Secondary sources are sources that analyze primary sources in some way and include things like magazine and journal articles that analyze study results, literature, interviews, etc.

When you use source material outside of your own experience, you’re using either primary or secondary sources. Primary sources are sources that were created or written during the time period in which they reference and can include things like diaries, letters, films, interviews, and even results from research studies. Secondary sources are sources that analyze primary sources in some way and include things like magazine and journal articles that analyze study results, literature, interviews, etc. Quotations are another way to integrate source information into your paragraphs, but you should use them sparingly.

Quotations are another way to integrate source information into your paragraphs, but you should use them sparingly. It’s your turn now to wrap up your research process and start thinking about how you’ll use sources and which sources you’ll use. Remember, you want to ensure you have quality sources, but those sources can come from your library’s databases, the web, and even interviews if your professor allows for them.

It’s your turn now to wrap up your research process and start thinking about how you’ll use sources and which sources you’ll use. Remember, you want to ensure you have quality sources, but those sources can come from your library’s databases, the web, and even interviews if your professor allows for them.