Part 3: Research

3 Rhetoric

What is Rhetoric?

Rhetoric is the study of effective speaking and writing. And the art of persuasion. And many other things.

The modes of persuasion you are about to learn about on the following pages go back thousands of years to Aristotle, a Greek rhetorician. In his teachings, we learn about three basic modes of persuasion—or ways to persuade people. These modes appeal to human nature and continue to be used today in writing of all kinds, politics, and advertisements.

These modes are particularly important to argumentative writing because you’ll be constantly looking for the right angle to take in order to be persuasive with your audience. These modes work together to create a well-rounded, well-developed argument that your audience will find credible.

By thinking about the basic ways in which human beings can be persuaded and practicing your skills, you can learn to build strong arguments and develop flexible argumentative strategies. Developing flexibility as a writer is very important and a critical part of making good arguments. Every argument should be different because every audience is different and every situation is different. As you write, you’ll want to make decisions about how you appeal to your particular audience using the modes of persuasion.

The video below provides you with an excellent example of how these modes work together, and the pages that follow will explain each mode in detail, focusing on strategies you can use as a student writer to develop each one. If you need the transcript, just click on the CC button at the bottom right of the video.

TED-Ed. (2013, January 14). Conner Neill: What Aristotle and Joshua Bell can teach us about persuasion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O2dEuMFR8kw

Content/Form

Rhetoric requires understanding a fundamental division between what is communicated through language and how this is communicated.

Aristotle phrased this as the difference between logos (the logical content of a speech) and lexis (the style and delivery of a speech).

Five Essential Elements of Greek Rhetoric

Invention-planning a discourse by deciding which arguments should be used and how supporting evidence should be deployed.

Arrangement-deciding on the most effective way to organize the arguments and supporting evidence.

Style -choosing effective language that fit the speaker’s character. the content of the speech and the occasion.

Memory-preparing for the speech through study and practice

Delivery-using the voice and body gestures in presenting the speech.

In written discourse, only the first three steps are involved.

Persuasive Appeals

Modes of Persuasion

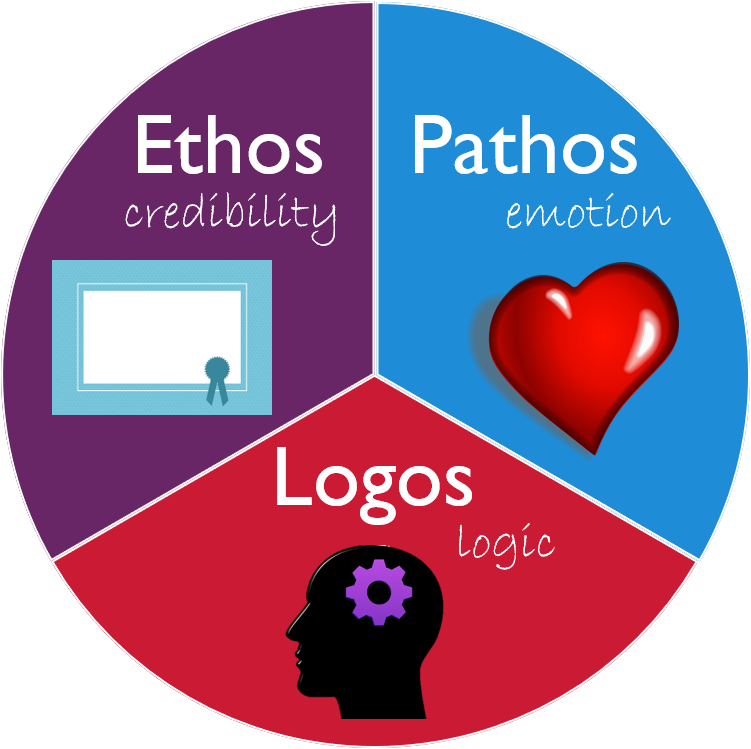

Persuasion, according to Aristotle and the many authorities that would echo him, is brought about through three kinds of proof or persuasive appeal:

logos: The appeal to reason. Using a coherent, consistent in manner. Compelling and convincing. Using the effective rules of logic. Inductive and deductive reasoning. Evidence.

pathos: The appeal to emotion. Appeals that relate to human emotions, especially the feelings and fractions of the audience. Appeal to the heart.

ethos: The persuasive appeal of one’s character. Personality, trustworthiness.

Although they can be analyzed separately, these three appeals work together in combination toward persuasive ends.

Logos

Logos is about appealing to your audience’s logical side. You have to think about what makes sense to your audience and use that as you build your argument. As writers, we appeal to logos by presenting a line of reasoning in our arguments that is logical and clear. We use evidence, such as statistics and factual information, when we appeal to logos.

Logos is about appealing to your audience’s logical side. You have to think about what makes sense to your audience and use that as you build your argument. As writers, we appeal to logos by presenting a line of reasoning in our arguments that is logical and clear. We use evidence, such as statistics and factual information, when we appeal to logos.

In order to develop strong appeals to logos, we have to avoid faulty logic. Faulty logic can be anything from assuming one event caused another to making blanket statements based on little evidence. Logical fallacies should always be avoided. We will explore logical fallacies in another section.

Appeals to logos are an important part of academic writing, but you will see them in commercials as well. Although they more commonly use pathos and ethos, advertisers will sometimes use logos to sell products. For example, commercials based on saving consumers money, such as car commercials that focus on miles-per-gallon, are appealing to the consumers’ sense of logos.

As you work to build logos in your arguments, here are some strategies to keep in mind.

- Both experience and source material can provide you with evidence to appeal to logos. While outside sources will provide you with excellent evidence in an argumentative essay, in some situations, you can share personal experiences and observations. Just make sure they are appropriate to the situation and you present them in a clear and logical manner.

- Remember to think about your audience as you appeal to logos. Just because something makes sense in your mind, doesn’t mean it will make the same kind of sense to your audience. You need to try to see things from your audience’s perspective. Having others read your writing, especially those who might disagree with your position, is helpful.

- Be sure to maintain clear lines of reasoning throughout your argument. One error in logic can negatively impact your entire position. When you present faulty logic, you lose credibility.

- When presenting an argument based on logos, it is important to avoid emotional overtones and maintain an even tone of voice. Remember, it’s not just a matter of the type of evidence you are presenting; how you present this evidence is important as well.

Pathos

Appealing to pathos is about appealing to your audience’s emotions. Because people can be easily moved by their emotions, pathos is a powerful mode of persuasion. When you think about appealing to pathos, you should consider all of the potential emotions people experience. While we often see or hear arguments that appeal to sympathy or anger, appealing to pathos is not limited to these specific emotions. You can also use emotions such as humor, joy, or even frustration, to note a few, in order to convince your audience.

Appealing to pathos is about appealing to your audience’s emotions. Because people can be easily moved by their emotions, pathos is a powerful mode of persuasion. When you think about appealing to pathos, you should consider all of the potential emotions people experience. While we often see or hear arguments that appeal to sympathy or anger, appealing to pathos is not limited to these specific emotions. You can also use emotions such as humor, joy, or even frustration, to note a few, in order to convince your audience.

It’s important, however, to be careful when appealing to pathos, as arguments with an overly-strong focus on emotion are not considered as credible in an academic setting. This means you could, and should, use pathos, but you have to do so carefully. An overly-emotional argument can cause you to lose your credibility as a writer.

You have probably seen many arguments based on an appeal to pathos. In fact, a large number of the commercials you see on television or the internet actually focus primarily on pathos. For example, many car commercials tap into our desire to feel special or important. They suggest that, if you drive a nice car, you will automatically be respected.

With the power of pathos in mind, here are some strategies you can use to carefully build pathos in your arguments.

- Think about the emotions most related to your topic in order to use those emotions effectively. For example, if you’re calling for a change in animal abuse laws, you would want to appeal to your audience’s sense of sympathy, possibly by providing examples of animal cruelty. If your argument is focused on environmental issues related to water conservation, you might provide examples of how water shortages affect metropolitan areas in order to appeal to your audience’s fear of a similar occurrence.

- In an effort to appeal to pathos, use examples to illustrate your position. Just be sure the examples you share are credible and can be verified.

- In academic arguments, be sure to balance appeals to pathos with appeals to logos (which will be explored on the next page) in order to maintain your ethos or credibility as a writer.

- When presenting evidence based on emotion, maintain an even tone of voice. If you sound too emotional, you might lose your audience’s respect.

Ethos

Appealing to ethos is all about using credibility, either your own as a writer or of your sources, in order to be persuasive. Essentially, ethos is about believability. Will your audience find you believable? What can you do to ensure that they do?

Appealing to ethos is all about using credibility, either your own as a writer or of your sources, in order to be persuasive. Essentially, ethos is about believability. Will your audience find you believable? What can you do to ensure that they do?

You can establish ethos—or credibility—in two basic ways: you can use or build your own credibility on a topic, or you can use credible sources, which, in turn, builds your credibility as a writer.

Credibility is extremely important in building an argument, so, even if you don’t have a lot of built-in credibility or experience with a topic, it’s important for you to work on your credibility by integrating the credibility of others into your argument.

Aristotle argued that ethos was the most powerful of the modes of persuasion, and while you may disagree, you can’t discount its power. After all, think about the way advertisers use ethos to get us to purchase products. Taylor Swift sells us perfume, and Peyton Manning sells us pizza. But, it’s really their fame and name they are selling.

With the power of ethos in mind, here are some strategies you can use to help build your ethos in your arguments.

- If you have specific experience or education related to your issues, mention it in some way.

- If you don’t have specific experience or education related to your issue, make sure you find sources from authors who do. When you integrate that source information, it’s best if you can address the credibility of your sources. When you have credible sources, you want to let your audience know about them.

- Use a tone of voice that is appropriate to your writing situation and will make you sound reasonable and credible as a writer. Controversial issues can often bring out some extreme emotions in us when we write, but we have to be careful to avoid sounding extreme in our writing, especially in academic arguments. You may not convince everyone to agree with you, but you at least need your audience to listen to what you have to say.

- Provide a good balance when it comes to pathos and logos, which will be explored in the following pages.

- Avoid flaws in logic—or logical fallacies—which are explored in another chapter of the book.

Modes of Persuasion Activity

After completing this activity, you may download or print a completion report that summarizes your results.

See It in Practice

Now that you have learned about the different modes of persuasion and their uses and seen some ethos, pathos, and logos analysis in action, it’s time to see how our student is doing with her argumentative essay process. Let’s look at how she plans to appeal to ethos, pathos, and logos in her essay.

Watch as our student explores her choices and what strategies she thinks will be most convincing.

Time to Write

It’s time to think about how you will appeal to ethos, pathos, and logos and, depending upon where you are in your process, maybe even draft a few rough paragraphs using your source material as support.

It’s time to think about how you will appeal to ethos, pathos, and logos and, depending upon where you are in your process, maybe even draft a few rough paragraphs using your source material as support.

Wherever you are in your process, it’s a good time to start thinking of the appeals and asking yourself questions about your own credibility, the credibility of your sources, how much emotion you want to convey, and what you can do to appeal to the logical thinking of your audience.

Write down your plans in a journal or in notes and share them with your professor and/or classmate for some additional feedback.

The key is to get started with your writing in each step and think, at least for right now, how you can appeal to ethos, pathos, and logos to make the most convincing argument possible?

Assignment Analysis

Analyzing Your Assignment and Thinking Rhetorically

Rhetoric can be defined as the ability to determine how to best communicate in a given situation. Although a thorough understanding of effective oral, written, and visual communication can take years of study, the foundation of effective communication begins with rhetoric. With this foundation, even if you are just starting out, you can become a more powerful, more flexible writer. Rhetoric is key to being able to write effectively in a variety of situations.

Every time you write or speak, you’re faced with a different rhetorical situation. Each rhetorical situation requires some thoughtful consideration on your part if you want to be as effective as possible.

Many times, when students are given a writing assignment, they have an urge to skim the assignment instructions and then just start writing as soon as the ideas pop into their minds. But writing rhetorically and with intention requires that you thoroughly investigate your writing assignment (or rhetorical situation) before you begin to write the actual paper.

Thinking about concepts like purpose, audience, and voice will help you make good decisions as you begin your research and writing process. These concepts will be explained in more detail below.

Purpose

Rhetorically speaking, the purpose is about making decisions as a writer about why you’re writing and what you want your audience to take from your work.

Rhetorically speaking, the purpose is about making decisions as a writer about why you’re writing and what you want your audience to take from your work.

There are three objectives you may have when writing a research paper.

- To inform – When you write a research paper to inform, you’re not making an argument, but you do want to stress the importance of your topic. You might think about your purpose as educating your audience on a particular topic.

- To persuade – When you write a research paper to persuade, your purpose should be to take a stance on your topic. You’ll want to develop a thesis statement that makes a clear assertion about some aspect of your topic.

- To analyze – Although all research papers require some analysis, some research papers make analysis a primary purpose. So, your focus wouldn’t be to inform or persuade, but to analyze your topic. You’ll want to synthesize your research and, ideally, reach new, thoughtful conclusions based on your research.

TIPS! Here are a few tips when it comes to thinking about purpose.

Audience Awareness

Who are you writing for? You want to ask yourself that question every time you begin a writing project. And you want to keep your audience in mind as you go through the writing process because it will help you make decisions while you write. Such decisions should include what voice you use, what words you choose, and the kind of syntax you use. Thinking of who your audience is and what their expectations are will also help you decide what kind of introduction and conclusion to write.

Who are you writing for? You want to ask yourself that question every time you begin a writing project. And you want to keep your audience in mind as you go through the writing process because it will help you make decisions while you write. Such decisions should include what voice you use, what words you choose, and the kind of syntax you use. Thinking of who your audience is and what their expectations are will also help you decide what kind of introduction and conclusion to write.

Your instructor, of course, is your audience, but you must be careful not to assume that he or she knows more than you on the subject of your paper. While your instructor may be well-informed on the topic, your purpose is to demonstrate your knowledge and fully explain what you’re writing about, so the reader can see that you have a good grasp on the topic yourself. Think of your instructor as intelligent but not fully informed about your topic. Think of your instructor as representing people from a particular field (historians, chemists, psychologists).

Another approach is to think of your audience as the people who make up the class for which you are writing the assignment. This is a diverse group, so it can be tough to imagine the needs of so many people. However, if you try to think about your writing the way others from a diverse group might think about your writing, it can help make your writing stronger.

Writing for Your Audience

Sometimes, it’s difficult to decide how much to explain or how much detail to go into in a paper when considering your audience. Remember that you need to explain the major concepts in your paper and provide clear, accurate information. Your reader should be able to make the necessary connections from one thought or sentence to the next. When you don’t, the reader can become confused or frustrated. Make sure you connect the dots and explain how information you present is relevant and how it connects with other ideas you have put forth in your paper.

As you write your essay, try to imagine what information your audience will need on your topic. You should also think about how your writing will sound to your audience, but that will be discussed more in the next section on Voice.

When it’s time to revise, read your drafts as a reader would, looking for what is not well explained, clearly written, or linked to other ideas. It might be useful to read your paper to someone who has no background in the topic you’re writing about to see if your listener can follow your argument. As always, your job as the writer is to communicate your thinking in a clear, thoughtful, and complete way.

Analyzing Your Audience

Because keeping your audience in mind as you engage in the writing process is important, it may be helpful to have a list of questions in mind as you think about your audience. The interactive worksheet below can be saved and printed if you want to keep it near your computer as you write.

See It in Practice

Now that you have read more about the importance of writing with your audience in mind, take a look at how this student considers her audience for the sample assignment she is working on.

Time to Write

In addition to completing the Analyzing Your Audience activity, it’s a good idea to write about your audience and share your thinking with your peers and your professor. Because you’re not writing just for your professor and have to anticipate the needs and knowledge of a fairly broad audience, it’s important to spend some time really thinking about how you will write appropriately for your academic audience.

Share your results from your Analyzing Your Audience activity as well as your notes or writing journal with your classmates. What similarities do you see between your own analysis and your classmates’? If you notice big differences, it would be wise to check with your professor.

Audience

Before you begin to write your research paper, you should think about your audience. Your audience should have an impact on your writing. You should think about the audience because, if you want to be effective, you must consider the audience’s needs and expectations. It’s important to remember the audience affects both what and how you write.

Before you begin to write your research paper, you should think about your audience. Your audience should have an impact on your writing. You should think about the audience because, if you want to be effective, you must consider the audience’s needs and expectations. It’s important to remember the audience affects both what and how you write.

Most research paper assignments will be written with an academic audience in mind. Writing for an academic audience (your professors and peers) is one of the most difficult writing tasks because college students and faculty make up a very diverse group. It can be difficult for student writers to see outside their own experiences and to think about how other people might react to their messages.

But this kind of rhetorical thinking is necessary for effective writing. Good writers try to see their writing through the eyes of their audience. This, of course, requires a lot of flexibility as a writer, but the rewards for such thinking are great when you have a diverse group of readers interested in and, perhaps, persuaded by your writing.

Intended Audience

Classmates and professors

For an academic audience of classmates and teachers, you have the task of considering a diverse group. You’ll want to think about how much background information your audience will need on your topic, as well as what terms will need to be defined. You’ll want to be sure to use a formal tone, as research papers for an academic audience generally require a tone that is quite formal.

Colleagues or potential colleagues

For an audience within your field, you’ll want to consider how much background information you’ll need to provide and what terms you need to define. You may not need to provide as much background information as you would for a diverse academic or general audience, and you wouldn’t want to define terms that would be considered common knowledge in your field. Your tone should be formal, as colleagues or potential colleagues in your field of study will expect a formal voice.

The general public

Although many research papers in college-level classes are intended for an academic audience, you may encounter assignments where instructors ask you to write for a general public type of audience. When you write for the general public, you may need to provide helpful background information, define important terms, and use a tone that is semi-formal.

Targetted Audience

Sometimes, an instructor will ask you to write for a specific public audience. When you write for a specific targetted audience, you are thinking about a specific group of readers the essay is intended to reach. When it comes to determining the most appropriate audience for the essay, it is necessary to think back to the purpose. The easiest way to do that is to put into your mind the action you would like to see taken after your essay has been read. Then, you can consider who would be able to take that action.

Example

Susan is writing an essay to promote the banning of single-use plastic straws in restaurants. She has decided to focus on encouraging the use of metal straws. There are three possible audiences that Susan is thinking of writing towards as she writes her essay

- First: Restaurant Owners

- Second: Restaurant Customers

- Third: City Lawmakers

Each audience would give Susan a different approach and different arguments to target. If she chooses restaurant owners, she can focus on the cost savings of the use of reusable metal straws. If she chooses customers, she thinks she would focus more on the ways customers could do their part and about some of the convenience of personal metal straws. Finally, Susan believes that focusing on lawmakers would mean she would need to talk about cities that have already banned straws and the arguments for the laws that have already been passed.

Each audience has different pros and cons. Susan carefully considers the type of paper she wants to write and the research she has done so far. In the end, Susan decides that customers are going to be the easiest for her to talk to in her essay.

Changing Audiences

Most people have a fairly strong sense of audience awareness. You were a natural rhetorician from the time you were a child when you worked to convince your parents to get you a certain toy. You probably honed your rhetorical skills with your parents during your teenage years. Most of us do.

Most people have a fairly strong sense of audience awareness. You were a natural rhetorician from the time you were a child when you worked to convince your parents to get you a certain toy. You probably honed your rhetorical skills with your parents during your teenage years. Most of us do.

But audience awareness can get a little more complicated when you have to write for a diverse audience or an audience you don’t know very well. Still, we can use what we do know about being effective for an audience and apply that to academic situations.

The important thing is to do your best to think about what might appeal to a particular group of people. In the samples below, you’ll see paragraphs written on the same topic to three different audiences. Which one would be most appropriate for a formal research paper required in an academic setting? Which one would be most effective within a group of friends or family, perhaps something you might see as a Facebook post for a class? Which one might work well as a journal entry, intended for just you and your teacher, for an education class? As you read through each paragraph, think about who the intended audience might be and how both content and style change in different situations, even though the topics are the same. Notice how the tone becomes more formal as you progress.

Samples

- Do you remember those awful standardized tests from high school? I mean, what good were they? I remember sitting in class while our English teacher told us for like the hundredth time that these tests were important, and then, she would show us the formula we were supposed to use to pass the written portion of the test. I got really good at that formula and passed the standardized test to graduate high school with flying colors. Then, I went to college and was lost. I got bad grades on my essays and didn’t know why.

- When I was in high school, states were just beginning to pass laws about standardized testing. I went to public school in a state that was one of the first states to have standardized testing requirements before a student could graduate. I know firsthand some of the problems associated with placing too much emphasis on standardized testing. My high school English teacher spent a lot of time teaching us the “formula” for the standardized test we had to take, but the only essays I wrote were for that exam. Then, when I went to college, I found I was quite unprepared. I was an “A” student in high school, but I was earning “Cs” on my essays in college. I remember the shame I felt about getting “bad” grades. Fortunately, I was able to get extra help from the university writing center, and I was able to turn things around for myself. But we should not have students entering college with so little and such limited writing experience. I have read so much research indicating that my experiences are not unique. Too many students are coming to college without very much experience in writing, and standardized tests are a part of the problem.

- Today, standardized tests are a part of everyday life at most public high schools in the United States. Thanks to legislation from the No Child Left Behind Act, students must now pass standardized tests before they can graduate from high school. While the legislation behind the No Child Left Behind Act may have been well-intentioned, there have been serious negative consequences to this act, one being a heavy focus on “teaching to the test” in many classrooms across the country. This focus on testing can lead to a loss in instructional time for things like critical thinking and writing. Research now indicates that, indeed, writing instruction has suffered due to an emphasis on standardized testing. Researchers Applebee and Langer studied writing assignments and writing instruction time in middle and high school classrooms throughout the United States. Applebee and Langer (2011) found “[T]he actual writing that goes on in typical classrooms across the United States remains dominated by tasks in which the teacher does all the composing…replicating highly formulaic essay structures keyed to the high-stakes tests they will be taking.” (p. 26). This emphasis on teaching writing “to the test” can have serious consequences for students entering college and the workforce. Because writing is such an important part of college classes and most professions, the U.S. needs to examine the consequences of high-stakes standardized testing, like those connected to the No Child Left Behind Act, on writing instruction in the public schools.

Offending an Audience

You have learned now that your writing isn’t just for you and that part of your role as a writer is to keep the audience in mind when you write. Some students struggle with this because it may feel like they just can’t say what they want to say when they have to write with their audience in mind. You may feel the same and feel like you want to share your ideas the way you want to share your ideas, no matter what an audience thinks.

However, you have to remember that, unless you’re keeping a personal journal, your writing is always for someone else as well. In fact, most of the time, you’re going to need to be highly aware of your audience’s needs when you are writing for college—and for work. Moreover, when you’re writing argumentative essays on controversial topics, if you want to be persuasive, you have to think about what is going to work well to be persuasive for your given audience. Will your audience listen to you if you offend them? Probably not.

With that in mind, you’ll want to make good rhetorical decisions when you write. This means you have to consider what language will work for your audience, what kind of evidence will be persuasive, and how you can present that evidence in the most convincing manner possible.

If you offend your audience, your audience members won’t listen to what you have to say. While you may not be able to always convince your audience to see your side of an issue, you should at least be able to get them to listen to you and consider your points.

In the video below, you’ll see what happens when audience members are offended and what their reactions are, and why. Seeing what happens for yourself may help you remember that, when you’re writing an argument, you are writing for someone else.

Voice

Once you have considered your audience and established your purpose, it’s time to think about voice. Your voice in your writing is essentially how you sound to your audience. Voice is an important part of writing a research paper, but many students never stop to think about voice in their writing. It’s important to remember voice is relative to audience and purpose. The voice you decide to use will have a great impact on your audience.

- Formal – When using a formal, academic or professional voice, you’ll want to be sure to avoid slang and clichés, like “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” You’ll want to avoid conversational tone and even contractions. So, instead of “can’t,” you would want to use “cannot.” You’ll want to think about your academic or professional audience and think about what kind of impression you want your voice to make on that audience.

- Semi-formal – A semi-formal tone is not quite as formal as a formal, academic, or professional tone. Although you would certainly want to avoid slang and clichés, you might use contractions, and you might consider a tone that is a little more conversational.

Students sometimes make errors in voice, which can have a negative impact on an essay. For example, when writing researched essays for the first time, many students lose their voices entirely to research, and the essay reads more like a list of what other people have said on a particular topic than a real essay. In a research essay, you want to balance your voice with the voices from your sources.

It’s also easy to use a voice that is too informal for college writing, especially when you are just becoming familiar with academia and college expectations.

Ultimately, thinking about your writing rhetorically will help you establish a strong, appropriate voice for your writing.

See It in Practice

In the video cast below, you’ll see our student writer discuss the rhetorical analysis she has written for her research paper assignment.

Time to Write

Now that you have had a chance to see how you can analyze your assignment rhetorically, it’s time to try it out. Using your own research essay assignment as your guide, take some time to write about your purpose, audience, and voice. Keeping a writing journal is a great way to give yourself an opportunity to keep track of your notes that you can refer back to later.

Does your assignment specify anything in particular? In your journal or in some notes, make a short list and, in a few sentences, describe what you think your purpose for writing might be, who might be in your target audience, and what voice or tone you plan to take in order to make a good impression on your audience. Then, share your notes or journal with your professor and classmates for feedback.

This is a good opportunity to think about your requirements and ask questions of your professor to make sure you’re understanding requirements related to your purpose, target audience, and what voice or tone would be appropriate.

ATTRIBUTIONS

- Content Adapted from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL). (2020). Excelsior College. Retrieved from https://owl.excelsior.edu/ licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License.