Crash Course in OER

Is This Ideal?

Imagine the following scenario:

A student thinks that some textbook purchases might be superfluous. This second-semester student at a community college is taking a full load of courses and plans to transfer to a university to pursue engineering. Grades have been generally good despite the thirty-plus hours a week working at a restaurant to support the family, but, now that a new semester is about to begin, another round of required textbooks are going to need to be purchased. The total lands somewhere around $500 in the process; the learning materials themselves cost almost as much as enrolling in another course.

As the semester progresses, it becomes painfully clear that pretty much the only section of the manual that the course consistently uses is that covering MLA style. She looks at the schedule in the syllabus and sees that only seven of the fifteen chapters of the reader are assigned. The investment that she’s made in these texts doesn’t seem sound at all, causing some serious consternation.

Now move to the instructor’s office, where the grading of a stack of mid-semester essays is happening. Noting that many students still need to work on composing an effective thesis statement, this faculty member flips through the manual to the appropriate section. The description provided by the text suddenly seems not satisfying at all, as if it’s missing something vital. The instructor then spends several hours, some over the weekend, putting together a presentation, complete with activities and an accompanying handout, which covers in satisfactory detail the concept of a thesis along with some ways to nail down an introduction to an academic essay. The students already bought the manual and reader, but the faculty member has decided that this new material is going to work better in the context of this specific group of students and makes it available through the course’s learning management system (LMS). Next week, students all agree that the presentation was very helpful, whereas only a few find the manual’s explanation worth their time. The instructor then discusses the weekend’s work with a colleague, who just so happened to spend a similar amount of time creating a similar teaching unit.

The inefficiency of this situation causes learners extra stress and teachers extra time. While definitely not ideal, chances are that, as students or as instructors, we have encountered a scenario like this. There are any number of ways to avoid this kind of unhelpful practice, such as selecting a more appropriate textbook or asking around for materials. However, the problem can be avoided completely with a small amount of work ahead of time, saving the student money, the instructor time, and enhancing the learning experience all the while. Sometimes all you have to do is find yourself some good OER to use or adapt.

How Much Do You Already Know about OER?

Crash Course Overview

No matter which role-playing experience you begin with in these materials, you’re going to want to have a basic understanding of what open educational resources and practices are all about. This “crash course” (we know, an unfortunate metaphor) is designed to establish the working knowledge you’ll need to fully immerse yourself in any one of the parts to come. Also note that we will be introducing some concepts and practices in this crash course that will be more thoroughly addressed in various contexts later in the material.

By the end of this crash course, you will be able to:

- A.1.1. Define ‘OER’ in your own words.

- A.1.2. Identify the “5R” permissions that characterize an open educational resource.

- A.1.3. Describe the differences between “open” and “free” in the context of open education.

Recommended Reading

- The Cape Town Open Education Declaration (2008)

- UNESCO Recommendation on OER (2019)

- Wikipedia: “Open Educational Resources” (Yeah, that’s right: Wikipedia)

Defining Open Educational Resources

There may be many definitions of “open educational resources” out there, but, for the most part, they differ little in outlining the characteristics that content must have in order to be considered open.

For a while, a commonly cited definition was provided by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation: “OER are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge.” More recently, the foundation has begun to use even more concise language to sum up OER: “freely licensed, remixable learning resources.”

UNESCO‘s 2019 recommendation on OER provides the following definition (I.1): “Open Educational Resources (OER) are learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright that have been released under an open license, that permit no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.”

It is also worth noting that a 2007 report published by UNESCO’s Virtual University (the original link has expired, so we have to use the Wayback Machine) provides a synthesis of characteristics of ideal OER as described by participants in a 2005 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) forum on OER:

- “The license under which an OER is released should mention precisely what is authorized in terms of adaptation and re-use.

- “OER should be published in a format that everyone can open, copy and paste from, and edit content in, without needing to install proprietary software.

- “To be re-usable easily, OER should be released in small chunks, or be easily separable into smaller chunks.

- “OER should be easy to search for and find. This means that resources should be described using standards-compliant metadata, to enable federated searching across a variety of search tools.

- “OER should be efficient (i.e. well designed and of high quality) for teaching and learning.”

Perhaps the most controversial of these characteristics is the requirement that digital materials be distributed in an open file format such as plain text or html, rather than a closed format such as Microsoft Word. Educators seeking to develop OER should keep in mind that shared materials can’t be successfully adopted if they can’t be opened. Because many people who have access to the internet can use “free” proprietary tools to open a variety of proprietary file types, many educators continue to generate and share resources using some of the more common file types rather than vying for open file formats. However, this runs the risk of excluding those around the world who, for a variety of reasons, might not have access to these tools. Ultimately, it is up to the author of the resource to consider the extent to which they want to maximize the openness of their materials by way of open source file formats.

Wikipedia, of course, provides an illuminating overview of the OER concept as well, touching on some of the changing definitions mentioned above as well as highlighting tensions surrounding the restrictiveness of definition:

The idea of open educational resources (OER) has numerous working definitions.[3] The term was first coined at UNESCO’s 2002 Forum on Open Courseware[4] and designates “teaching, learning and research materials in any medium, digital or otherwise, that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions. Open licensing is built within the existing framework of intellectual property rights as defined by relevant international conventions and respects the authorship of the work”.[5]

Often cited is the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation term which used to define OER as:

OER are teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others. Open educational resources include full courses, course materials, modules, textbooks, streaming videos, tests, software, and any other tools, materials, or techniques used to support access to knowledge.[6]

The Hewlett Foundation updated its definition to:

“Open Educational Resources are teaching, learning and research materials in any medium – digital or otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions[7]“. The new definition explicitly states that OER can include both digital and non-digital resources. Also, it lists several types of use that OER permit, inspired by 5R activities of OER.[8][9]

5R activities/permissions were proposed by David Wiley, which include:[10]

- Retain – the right to make, own, and control copies of the content (e.g., download, duplicate, store, and manage)

- Reuse – the right to use the content in a wide range of ways (e.g., in a class, in a study group, on a website, in a video)

- Revise – the right to adapt, adjust, modify, or alter the content itself (e.g., translate the content into another language)

- Remix – the right to combine the original or revised content with other material to create something new (e.g., incorporate the content into a mashup)

- Redistribute – the right to share copies of the original content, your revisions, or your remixes with others (e.g., give a copy of the content to a friend)[11]

Users of OER are allowed to engage in any of these 5R activities, permitted by the use of an open license.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines OER as: “digitised materials offered freely and openly for educators, students, and self-learners to use and reuse for teaching, learning, and research. OER includes learning content, software tools to develop, use, and distribute content, and implementation resources such as open licences”.[12] (This is the definition cited by Wikipedia’s sister project, Wikiversity.) By way of comparison, the Commonwealth of Learning “has adopted the widest definition of Open Educational Resources (OER) as ‘materials offered freely and openly to use and adapt for teaching, learning, development and research'”.[13] The WikiEducator project suggests that OER refers “to educational resources (lesson plans, quizzes, syllabi, instructional modules, simulations, etc.) that are freely available for use, reuse, adaptation, and sharing’.[14][15]

The above definitions expose some of the tensions that exist with OER:

- Nature of the resource: Several of the definitions above limit the definition of OER to digital resources, while others consider that any educational resource can be included in the definition.

- Source of the resource: While some of the definitions require a resource to be produced with an explicit educational aim in mind, others broaden this to include any resource which may potentially be used for learning.

- Level of openness: Most definitions require that a resource be placed in the public domain or under a fully open license. Others require only that free use to be granted for educational purposes, possibly excluding commercial uses.

These definitions also have common elements, namely they all:

- cover use and reuse, repurposing, and modification of the resources;

- include free use for educational purposes by teachers and learners

- encompass all types of digital media.[16]

Given the diversity of users, creators and sponsors of open educational resources, it is not surprising to find a variety of use cases and requirements. For this reason, it may be as helpful to consider the differences between descriptions of open educational resources as it is to consider the descriptions themselves. One of several tensions in reaching a consensus description of OER (as found in the above definitions) is whether there should be explicit emphasis placed on specific technologies. For example, a video can be openly licensed and freely used without being a streaming video. A book can be openly licensed and freely used without being an electronic document. This technologically driven tension is deeply bound up with the discourse of open-source licensing. For more, see Licensing and Types of OER later in this article.

There is also a tension between entities which find value in quantifying usage of OER and those which see such metrics as themselves being irrelevant to free and open resources. Those requiring metrics associated with OER are often those with economic investment in the technologies needed to access or provide electronic OER, those with economic interests potentially threatened by OER,[17] or those requiring justification for the costs of implementing and maintaining the infrastructure or access to the freely available OER. While a semantic distinction can be made delineating the technologies used to access and host learning content from the content itself, these technologies are generally accepted as part of the collective of open educational resources.[18]

Since OER are intended to be available for a variety of educational purposes, most organizations using OER neither award degrees nor provide academic or administrative support to students seeking college credits towards a diploma from a degree granting accredited institution.[19][20] In open education, there is an emerging effort by some accredited institutions to offer free certifications, or achievement badges, to document and acknowledge the accomplishments of participants.

In order for educational resources to be OER, they must have an open license. Many educational resources made available on the Internet are geared to allowing online access to digitised educational content, but the materials themselves are restrictively licensed. Thus, they are not OER. Often, this is not intentional. Most educators are not familiar with copyright law in their own jurisdictions, never mind internationally. International law and national laws of nearly all nations, and certainly of those who have signed onto the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), restrict all content under strict copyright (unless the copyright owner specifically releases it under an open license). The Creative Commons license is the most widely used licensing framework internationally used for OER.[21]

And, as you can probably guess, you’ll find lots and lots of additional discussion just by conducting a basic web search using the term.

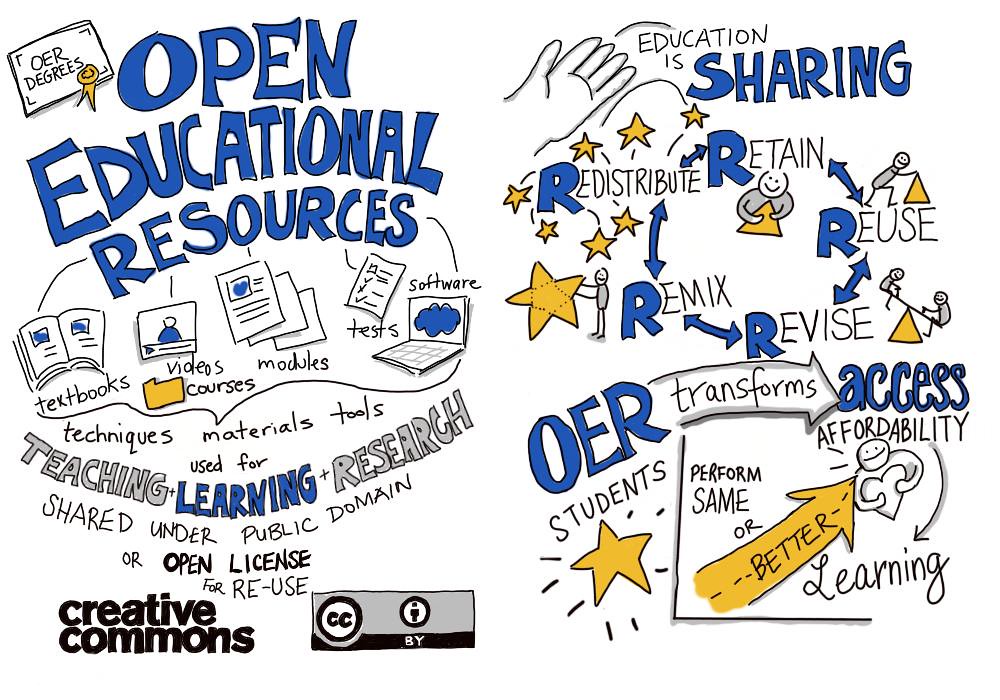

For a helpful visual definition of OER (and a representation of some of its promise), behold the following diagram:

Byte

“Open Educational Resources” is an evolving term that may be defined in different ways, but the core characteristics tend to be that they consist of materials used for learning that are available in the public domain or under an open license that permits the “5R’s”: Retain, Reuse, Redistribute, Revise, and Remix.

Engage

Consider how you would define “open educational resources,” based both on what you’ve read here and other experiences that you’ve had. Are there any key characteristics that you think are lacking in these common definitions?

Here are a few attempts to capture the essence of OER in just a few seconds:

(clip(s) from video(s))

Quiz Moment

Licenses and Attributions

“Open Educational Resources.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_educational_resources. CC BY-SA.