3.5 Igneous Rocks

Charlene Estrada

Magma forms under the Earth’s surface at about 800 to 1300°C in the crust or mantle and erupts on Earth’s surface as lava. When magma or lava cools, it solidifies by crystallization in which minerals grow within the magma or lava. The rock that results from this is an igneous rock from the Latin word ignis, meaning “fire.” [2] Igneous rocks are traditionally defined as the solid products from the cooling and hardening of molten magma in many different environments. Composition and texture identify these rocks.

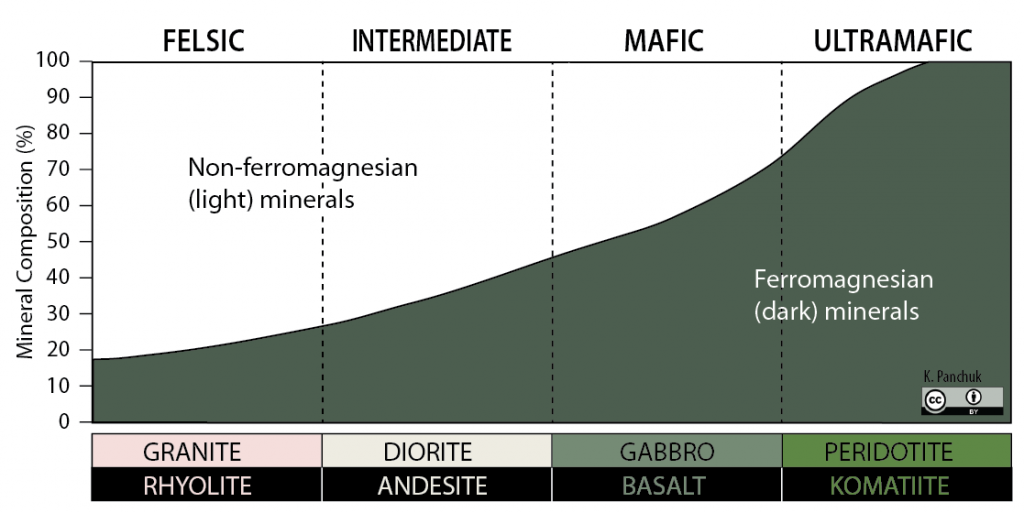

Igneous Rock Composition

Composition refers to a rock’s chemical and mineralogical make-up. For an igneous rock, composition is generally divided into four groups: ultramafic, mafic, intermediate, and felsic. These groups refer to differing amounts of silica (SiO2), iron (Fe), and magnesium (Mg) found in the minerals that make up the rocks.

Ultramafic refers to rocks composed of mostly olivine and some pyroxene. These rocks have even more magnesium and iron and even less silica than ‘ordinary’ mafic rocks. Ultramafic rocks are rare on the surface, but they make up the primary composition of the upper mantle. Ultramafic rocks are very poor in silica, in the 40% or less range (this means that the rock would be less than 40 weight percent silica).

Mafic refers to igneous rocks with an abundance of ferromagnesian minerals (those with the elements Mg and Fe in their chemical formulae) plus plagioclase feldspar. Such minerals are dark-colored and include pyroxene and olivine. Mafic rocks are low in silica (in the 45-50% range), but they make up the majority of the oceanic crust and lithosphere.

Intermediate describes the igneous rock composition between mafic and felsic. It contains roughly equal amounts of light and dark minerals, including light grains of plagioclase feldspar and dark grains of amphibole. It is intermediate in silica (in the 55-60% range).

Felsic refers to a predominance of light-colored minerals, including Feldspar and silica (quartz). These minerals have more silica as a proportion of their overall chemical formulae. Minor amounts of dark-colored minerals, such as biotite mica, may sometimes be present. Felsic igneous rocks are rich in silica (in the 65-75% range), and they tend to represent the composition of the continental crust or lithosphere.

Igneous Rock Texture

If magma cools slowly, deep within the crust, the resulting rock is called intrusive. The slow-cooling process beneath the surface allows crystals to grow large, giving the rock a coarse-grained or “phaneritic” texture. The individual crystals in a coarse-grained texture are visible to the unaided eye.

When lava is erupted onto the surface or rises into shallow in a mountain and cools, the rock that will cool from it is called an extrusive igneous rock. Extrusive igneous rocks have a fine-grained or “aphanitic” texture, in which the grains are too small to see with the unaided eye. This fine-grained texture tells us that the quickly-cooling lava did not have time to grow large crystals.

Some igneous rocks have a mixture of large crystals within a fine-grained matrix. Such a texture is called porphyritic. A porphyritic texture tells us that the magma underwent multiple stages of cooling; it first cooled slowly when it was deep under the surface, and then it rose to a shallow depth where it cooled quickly.

All magmas contain dissolved gases called volatiles. When magma quickly rises to the surface as lava, these volatiles sometimes become trapped in the cooling molten rock and form a bubbling texture that appears sponge-like. Such a texture is called vesicular because the holes in the rock are called vesicles by scientists.

Lava will sometimes cool so quickly that not even microscopic crystals will form in it. As a result, volcanic glass will form with a shiny, smooth appearance that reflects light. This texture is called glassy. Just like the mineral quartz, a glassy rock will have conchoidal fracture with distinctive, rounded fracture edges. This is because, like quartz, most glassy rocks are made of the compound SiO2 in the form of the mineraloid amorphous silica.

The final volcanic texture is a result of explosive, violent eruptions. These eruptions produce not only lava, but clouds of ash, rock, gases, and glass. The solid material of the eruption, which is called tephra, eventually falls back onto the Earth and consolidates into a solid mass. The rock that will form from this process has a pyroclastic texture. This texture consists of volcanic ash, glass shards, and small rock fragments.

Igneous Rock Field Guide

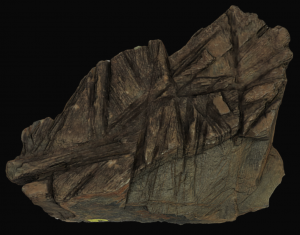

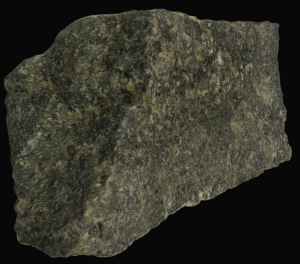

Komatiite

“KO-MAT-EE-ITE”

Most commonly confused with: Basalt

An ultramafic, fine-grained (extrusive) igneous rock. This rock will form from rapidly cooling lava, but it is very rare. Molten ultramafic rock was more prevalent on early Earth, and it can be found in the mantle. Komatiite is composed primarily of olivine and pyroxene minerals, which causes the rock to take on a dark, greenish color.

Chances are that if you are holding a fine-grained, dark igneous rock, it will be basalt since komatiites are not very common but look twice if it has a strong green tint. Olivine and pyroxene are more susceptible to weathering than minerals found in felsic rocks; therefore, this igneous rock may erode easier than a felsic counterpart.

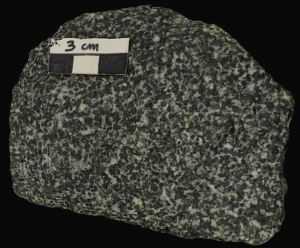

Peridotite

“PUR-ID-DO-TITE”

Most commonly confused with: Olivine (mineral), Gabbro

An ultramafic, coarse-grained (intrusive) igneous rock. Peridotite will form under the Earth’s surface from slowly-cooling magma. It is less rare than Komatiite, but still not very common. Ultramafic magma composes the Earth’s upper and lower mantle; therefore, when a plume of magma rises to the lithosphere and cools as a “Xenolith“, peridotite will form.

Peridotite is composed of visible, and sometimes large, crystals of olivine and pyroxene. It is often dark and with distinctively green crystals. When distinguishing this rock from gabbro, consider the percentage of olivine in the rock; peridotite has at least more than 25%. As with komatiite, peridotite will also erode more easily than other igneous rocks because it contains minerals that are more susceptible to weathering.

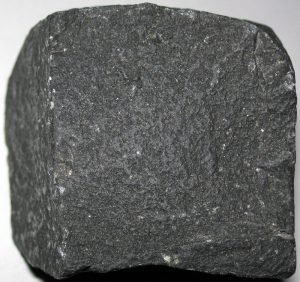

Basalt

“BAH-SALT”

Most commonly confused with: Komatiite, Shale (sedimentary), Limestone (sedimentary)

A mafic, fine-grained (extrusive) igneous rock. About 90% of all volcanic rocks that form are on the Earth’s surface are basalt as this rock represents a common magma composition of the upper mantle mixed with the crust. When this magma erupts as lava and cools, basalt is the final product.

Basalts are characterized by low (~50%) silica content and minerals with iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg). Such minerals typically include amphibole and pyroxene, and sometimes small amounts of olivine. Additionally, basalts include a significant amount of calcium-plagioclase feldspar in their matrix. Basalt often is dark gray, and unlike komatiite, does not have a green tint. When distinguishing this rock from shale and limestone, use a hand lens to identify the notable minerals in its matrix. Additionally, basalt is more resistant to scratching than shale and limestone; try scratching it with a penny!

The elevated iron content in basalt makes this rock easier to rust and erode under Earth’s atmosphere. As a mafic rock, it is more susceptible to weathering than felsic igneous rocks.

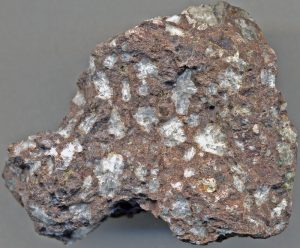

Gabbro

“GAB-BRO”

Most commonly confused with: Peridotite

A mafic, coarse-grained (intrusive) igneous rock. Gabbro makes up the majority of oceanic lithosphere, and it often forms at divergent boundaries when magma with a composition similar to the upper mantle rises and slowly cools beneath the surface. This rock has the same general composition as basalt, but its minerals are easily visible to the naked eye due to its slow cooling history.

Gabbro is dark gray or black, sometimes with noticeable flecks of white calcium plagioclase or green olivine. Gabbro can be distinguished from peridotite by its limited olivine content. If the number of olivine crystals in an unknown, coarse-grained rock is small or nonexistent, then you are looking at gabbro.

Like basalt, gabbro will erode at Earth’s surface at a faster rate than other felsic, intrusive rocks. The effects of weathering by the atmosphere may be more noticeable on gabbro because it contains larger crystals of iron-rich minerals.

Andesite

“AN-DEH-SITE”

Most commonly confused with: Rhyolite

An intermediate, extrusive igneous rock. Andesite cools from lavas that are between mafic and felsic in composition. As such, andesite typically has a silica content of 55-60%. Andesite can often be found near volcanoes along the Pacific Ring of Fire or at stratovolcanoes, which are sometimes called Andesite volcanoes. Andesitic lavas are typical of subduction zones, such Andes Mountains subduction zone for which it received its name.

Andesite is commonly light gray. Unlike other extrusive igneous rocks that cool from lava, andesite is also porphyritic, which means that medium and small dark crystals can be seen in its fine-grained matrix by the naked eye. These crystals are usually amphibole and pyroxene minerals, whereas the light matrix is mostly composed of calcium plagioclase feldspar. The porphyritic texture of andesite clearly distinguishes it from rhyolite, which is sometimes a light beige-grey color.

Andesite is primarily composed of the silica-rich mineral Ca-plagioclase, which is resistant to weathering at the Earth’s surface; however, its pyroxene and amphibole minerals are just as vulnerable to chemical erosion by the atmosphere as those in basalt. This rock is more resistant to weathering than mafic rocks, but felsic rocks will last longer.

Diorite

“DYE-O-RITE”

Most commonly confused with: Granite

An intermediate, coarse-grained (intrusive) igneous rock. Diorite cools slowly from molten rock that forms beneath the Earth’s surface along subduction zones, such as the Andes Mountains and other convergent margins at the Ring of Fire.

Diorite has a “cookies and cream” or “Dalmation”-like appearance, which is caused by black amphibole and white plagioclase crystals that are easily identifiable by the naked eye. Although this rock is much lighter in color than gabbro, it should be easily distinguished from granite due to the abundance of dark crystals in its matrix.

Like andesite, the calcium-rich plagioclase mineral in diorite will be resistant to weathering; however, the dark amphibole minerals are more likely to be oxidized (rusted) by Earth’s atmosphere over long periods of time.

Rhyolite

“RYE-O-LITE”

Most commonly confused with: Andesite, Tuff

A felsic, fine-grained (extrusive) igneous rock. Rhyolite rapidly cools from a high-silica (65-75%) lava. Rhyolite is not as common as its coarse-grained counterpart, granite, because felsic lavas cannot move very far once they erupt.

Rhyolite is typically light tan to pinkish tan in color, and individual crystals are usual difficult to see with the naked eye. Therefore, this rock can be distinguished from andesite, which often has medium and small crystals within its matrix. There are also no pyroclastic debris within rhyolite, which can be confirmed by examining the rock under light; unlike tuff, rhyolite does not have visible flecks of volcanic glass in its matrix.

Rhyolite can be found at explosive volcanoes, such as at Yellowstone National Park. It is primarily made of quartz, which is very resistant against physical and chemical weathering. As a result, rhyolite formations are very stable on the Earth’s surface.

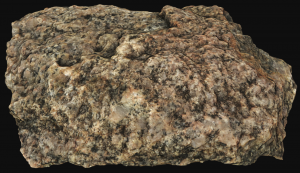

Granite

“GRAN-IT”

Most commonly confused with: Diorite

A felsic, coarse-grained (intrusive) igneous rock. Granite is often used to approximate the composition of the continental crust in both composition and density. This estimation is typical because granite usually forms within the cores of mountains and thick lithosphere when magma with high silica content slowly cools and crystallizes.

Granite can be identified by its light to pinkish color, and the presence of abundant quartz. Granite commonly has large amounts of salmon-pink potassium feldspar and white, sodium-feldspar (plagioclase), which can even have visible cleavage planes on the crystals. Some varieties of granite have black flecks in the matrix, which are typically biotite mica. To distinguish granite from the intermediate coarse-grained rock, diorite, examine the minerals in its matrix carefully. Granite, unlike diorite, has few dark minerals, and a tendency to have more pink K-Feldspar.

Granite is among the most resistant igneous rocks to both mechanical and chemical weathering. It has been used in society in construction and manufacturing trades, and it has more popularly been used in interior decorating for the last several decades.

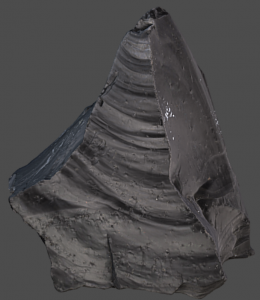

Obsidian

“OB-CID-DEE-AN”

Most commonly confused with: Chert (sedimentary)

A felsic, glassy (extrusive) igneous rock. Obsidian is commonly found along cooled lava fields with rhyolite. Obsidian forms when lava cools so quickly it does not have time to even develop microscopic crystals. When cooled, obsidian is very smooth, brittle, and shiny. Although obsidian is felsic and has a high silica content, is often black, brown, or red.

Obsidian is usually identifiable by its glassy texture alone. Like the mineral quartz, it displays conchoidal fracture, which can appear as curved or rounded fracture edges. The sedimentary rock chert, which is mostly composed of silica, also has conchoidal fracture; however, this rock is often much duller in both luster and color.

Because obsidian is both brittle and hard, it has been traditionally used as tools and weapons by indigenous people for thousands of years. Many of these weapons hold an edge after centuries, which demonstrate this rock’s resistance to weathering.

BACKYARD GEOLOGY: APACHE TEARS

Volcanic deposits are common throughout Southwestern United States, and these rocks have played an important role Native American culture and history. Obsidian can be reshaped and carved to form surgical instruments or weapons such as knives. There are also naturally occurring varieties of rounded obsidian that are said to absorb grief and depression. Today these stones are called “Apache Tears”. There are variations in the folklore behind this stone, each story is united by the tragic theme of loss.

The most popular legend behind the Apache Tears focuses upon a Pinal Apache Tribe that was vastly outnumbered by the U.S. military during the nation’s westward expansion in the 1800s. The majority of the the warriors were killed in a surprise raid near Picacho Peak. The remaining Native Americans threw themselves over the cliff rather than be taken prisoner or executed.

The family of the warriors gathered not far from the peaks, where the remains of the brave warriors could be found at the base. The women grieved deeply, day and night, for their lost men. The Great Father placed their tears in the obsidian. Should a person find one of these stones, they would not need to grieve since the women of the Pinal Apache Tribe have already given their tears inside the stone [3].

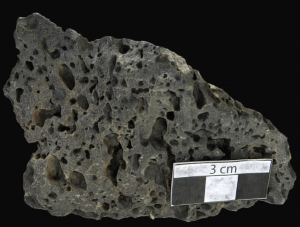

Scoria

“SCOR-EE-AH”

Most commonly confused with: Pumice

A mafic, vesicular (extrusive) igneous rock. Scoria forms when lava containing volatile gases erupts. The gases trapped within the lava form large cavities, or vesicles, as it rapidly cools at the surface. Scoria cools from mafic lava, and contains microscopic crystals of silica-poor, ferromagnesian minerals such as amphibole, pyroxene, and calcium plagioclase.

Scoria is usually dark gray in color and is easily distinguished from other mafic rocks by its vesicular texture. Although pumice is also vesicular, scoria is much darker and denser. Despite having large cavities, scoria will never float above water.

Some varieties of scoria are rust-red in color, which reflects the tendency of the minerals within the mafic rock to oxidize under Earth’s atmosphere. Furthermore, the abundant vesicles make a greater surface area available for weathering, which cause this rock to weather at a faster rate in comparison to other mafic rocks.

Pumice

“PUHM-IS”

Most commonly confused with: Tuff, Scoria

A felsic, vesicular (extrusive) igneous rock. Pumice forms when felsic lava, which can contain a significantly higher amounts of volatile gases, very rapidly cools. As with scoria, the cooling rock traps many vesicles of gas, and it takes on a “frothy” appearance as it solidifies. Pumice often cools too quickly to form minerals, and it is sometimes referred to as a volcanic glass. This rock can be found along the slopes of explosive volcanoes with pyroclastic deposits.

Pumice is usually light tan, pink, or gray. It is very low density, and most varieties contain enough vesicles that when placed in a bowl or cup of water, the rock will float. This unique characteristic will often distinguish pumice from similar-looking rocks such as tuff or scoria.

[Video Description: The pumice depicted in the video is beige and filled with small holes. It is very low density, and when placed in a bowl of water, it floats.]

Pumice does not typically contain minerals, but it is silica-rich, and therefore more resistant to erosion than scoria. It has been more popularly used in society as a cleaning and beauty tool. Nonetheless, like scoria, this rock has more exposed surface area than granite and rhyolite, and it will be more susceptible to weathering over geologic time.

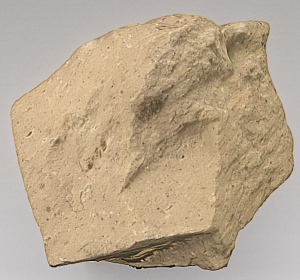

Tuff

“TOUGH”

Most commonly confused with: Pumice, Rhyolite

A felsic to intermediate, pyroclastic igneous rock. Tuff forms from the solid debris or tephra of an explosive volcanic eruption. When ash, volcanic glass, and rock fragments are ejected by the volcano or related pyroclastic flow eventually accumulate together, they form tuff. This type of rock usually indicates a violent eruption, and it is commonly found along the Ring of Fire and stratovolcanoes.

Tuff often does not have any single distinguishing mineralogical composition, although it often contains angular rock fragments and shiny flecks of glass within a fine-grained matrix of ash. Tuff is typically pale tan or gray in color. Its pyroclastic texture sometimes makes it less dense than other volcanic rocks; however, unlike pumice, it does not flow in water.

This activity is just for practice. It does not count toward your score!

molten rock that can be found beneath the Earth's surface.

The thin, outermost layer of Earth composed of rigid rock, which is home to all known life on the planet.

A hot interior layer of solid rock between the crust and core that is capable of plastic flow. The mantle is the largest layer of Earth.

molten rock that has erupted at the Earth's surface due to volcanic processes.

The process in which another substance, usually a fluid, becomes a solid and grows minerals.

a solid, inorganic, and crystalline substance that has a predictable chemical composition and form by natural processes.

Rocks that crystallize from molten materials beneath the Earth surface or from volcanic processes.

A magnesium and iron rich rock that contains very little silica.

(Mg,Fe)SiO4

A class of silicate mineral that forms at high temperatures and can have a magnesium (Mg) or iron (Fe) rich composition.

(Mg,Ca,Fe)SiO3

A class of dark-colored silicate minerals that form under high temperatures and/or pressures. These form in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The outermost layer of the Earth's mantle, which contains both the lower lithosphere and upper asthenosphere. This layer is susceptible to convection currents and plastic flow.

Originating from an iron and magnesium-rich magma/lava composition.

A class of light-colored feldspar that forms at higher temperatures and can be either sodium (Na) or calcium (Ca) rich.

A type of rigid, thin crust made of iron and magnesium rich minerals that is found beneath the planet's oceans.

A composition of igneous rocks, magma, and lava that is between felsic and mafic.

a class of silicate minerals that are usually dark and form long crystals (as prisms or needles). Amphiboles are often magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) rich in composition.

originating from a feldspar and silica-rich magma/lava composition.

A group of silicate minerals which represents the most abundant mineral class of the continental crust.

A very common rock-forming silicate mineral with formula SiO2.

Thick crustal material mostly made of feldspar and silica rich minerals which forms the world's large landmasses.

coarse-grained igneous rock texture with visible crystals within the matrix.

Describing an igneous rock texture in which individual mineral grains are visible to the unaided eye. Also known as coarse-grained.

Fine-grained, or microcrystalline, igneous rock texture.

Describing an igneous rock texture in which mineral grains are not clearly visible to the unaided eye. Also known as fine-grained.

an igneous rock texture that includes large visible crystals within a fine-grained matrix.

compounds that can easily take on a gaseous form

an igneous rock texture that is porous or contains many holes formed by escaping gases.

Rounded holes or cavities in solid rock that are formed by escaping gases.

an igneous rock texture that is smooth, shiny, and often forms by rapidly cooling lava on Earth's surface.

The breakage of a rock or mineral that forms smooth, curved surfaces.

solid substances, typically in rocks, that fall short of the definition of "mineral".

ejected rock and particle fragments from volcanic eruptions.

consisting of the debris from a volcanic explosion such as ash, glass, and rock fragments. Refers to igneous rock texture or unconsolidated materials.

an igneous rock that is mafic and fine-grained. Basalt is dark and makes up the majority of the oceanic crust.

an ultramafic, fine-grained igneous rock that is primarily composed of olivine and pyroxene.

A mafic, coarse-grained igneous rock that is often dark-colored. Gabbro makes the majority of the Earth's oceanic crust beneath the surface.

an ultramafic, coarse-grained igneous rock that forms from magma and is primarily composed of olivine and pyroxene.

The deeper of the two mantle layers in Earth's interior, also called the mesophere. The lower mantle is hotter and more rigid than the upper mantle.

a piece of rock in volcanic deposits that is not from the source magma, but that was created from another process.

the process in which a material is worn away by a stream of liquid (water) or air, often due to the presence of abrasive particles in the stream

The process of physically or chemically breaking down, transforming, or dissolving existing rock with contact by water, the atmosphere, or biosphere.

A clastic sedimentary rock made of very fine-grained sediments such as muds, clays, and silts.

An organic or chemical sedimentary rock that is primarily composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Limestone is a subgroup of rocks that includes chalk, coquina, and fossiliferous limestone.

A region along Earth's lithosphere where at least two tectonic plates move apart from one another.

A felsic, extrusive igneous rock that is light-colored. Rhyolite forms by volcanic lava flows and it is light-colored.

An intermediate, extrusive igneous rock. Andesite has a porphyritic texture.

A region extending along the islands and coastlines bordering the Pacific ocean that is affected by convergent and transform plate boundaries. These boundaries cause a higher incidence of earthquakes and volcanoes.

A tall and steep conically-shaped volcano built upon past layers of hardened ash and lava flows. Also known as a composite volcano.

The process in which the older, denser tectonic plate at a convergent boundary will buckle and sink into the lithosphere. This plate will always be composed of oceanic lithosphere.

A felsic, intrusive rock with coarse-grained texture. Granite composes mountain cores and can be found on and within the continental crust.

An intermediate, extrusive igneous rock that is coarse-grained. The presence of large black and white crystals on the rock have a "dalmation"-like appearance.

A region along Earth's lithosphere where at least two tectonic plates collide with one another.

A chemical weathering process in which the oxygen in the atmosphere causes the atoms or molecules within a substance to lose electrons. As a result, the substance takes on new properties (i.e., iron rusting).

An igneous rock composed of the accumulated products of a volcanic eruption, such as ash, glass, lava, and debris. Tuff has a pyroclastic texture.

A type of weathering that involves the abrasion and breakdown of existing rocks and minerals by water, the atmosphere, and biosphere. Also known as mechanical weathering.

The dissolution, disintegration, and alteration of preexisting rock by reactions that take place at the molecular scale.

The measure of how tightly packed atoms are in an object or material in a given volume. It is determined by figuring out its mass, divided by its volume.

The outer, relatively rigid layer of the Earth that is composed of crust and upper mantle.

A type of potassium feldspar that is orange-pink in color. It is more abundant of the K-Feldspars and often found in granite.

the breakage of minerals along smooth, planar surfaces that are parallel to atomic planes in its structure.

A type of mica that is black or dark-colored and is typically found in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

A chemical, or sometimes biological, sedimentary rock made of microcrystalline silica that has precipitated from water.

rocks that cement together from weathering products, either from sediments or chemical ions in water.

A felsic, extremely smooth, fine-grained igneous rock that is glassy in texture. Obsidian is primarily composed of amorphous silica and displays conchoidal fracture.

A vesicular, extrusive igneous rock that is felsic. Pumice is light-colored and low density, and it often floats atop water.

A mafic, vesicular igneous rock. Scoria is dark-colored, extrusive, and contains many cavities. However, it cannot float on water.

Gases dissolved within magma or lava.

A mixture of super-heated gas, ash, volcanic glass, and rock fragments that rapidly moves downslope from 60 to over 400 mph.