4.4 Monitoring Volcanoes

Charlene Estrada

Predicting Volcanic Eruptions

[Video Description: Images of molten lava at active volcanic craters. “Volcanoes are SO HOT right now. SO HOT that globally around 40 volcanoes erupt each month. Clip of hydrothermal vent. “Along with hundreds more erupting on the seafloor.” Video of lava. “EACH MONTH. And every eruption is an opportunity to learn about what’s happening deep, deep within the Earth.” Video of white volcanic gases. “In addition to lava and ash, these portals to the deep emit gases. Water, carbon and sulfur from within Earth provide valuable clues about how our planet works. Collecting these gases might look cool, but it’s the HOTTEST job in science.” Video of Jeep driving down the road. “By 2019, the Deep Carbon Observatory will TRIPLE the number of continuous volcanic gas monitoring stations worldwide, collecting real-time data in some of the most remote places on Earth.” World map of earthquakes, eruptions, and gas emissions. “When pieced together, this information helps reveal the story of deep carbon. Measuring these gases may even help us forecast future volcanic eruptions, and that’s not just a bunch of HOT AIR.” Video of erupting stratovolcano by a town.]

Scorching temperatures, toxic gases, and let’s not forget the volcanic bombs! Monitoring volcanoes is an extremely dangerous job, and it comes as no surprise that volcanology routinely appears among the top ten deadliest professions in the world! Nevertheless, there are scientists, as you have seen in the video above, who take the risk to monitor volcanoes because it may reduce the chance of a potential eruption taking a populated region by surprise.

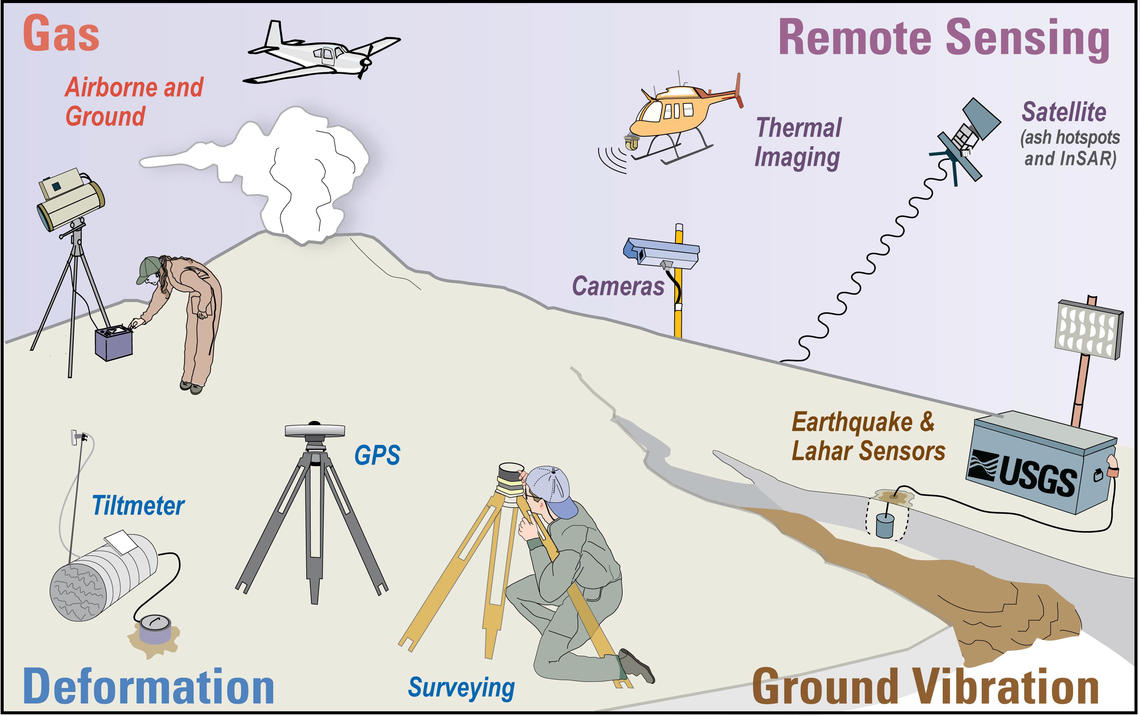

It is difficult to accurately predict whether or when a volcano will erupt, but scientists closely monitor a volcano over time to look for changes that could indicate geologic activity. Scientists will measure characteristics such as seismic activity surrounding the volcano, the deformation of the cone, gas emissions, and past history of volcanic eruptions [1,6]. These measurements will lead scientists to advise officials to take decisive action that can lead to evacuations, and hopefully, the prevention of a catastrophe.

History of Volcanic Activity

How active is a volcano? Scientists try to compile historical records from cities, towns, and villages surrounding a volcano to learn when, over the course of written history, it last erupted. Geologists can also examine the cooled lava fields along the slopes of a volcano, and even date some of the recently deposited ash and rock, to determine when it was last ejected from the vent.

Volcanoes are broadly placed into four categories: erupting, dormant, active, and extinct. An erupting volcano, as the name suggests, is currently having an ongoing eruption. A volcano that is not erupting, but still has a source of magma that enables it to eventually erupt one day is called dormant. If a volcano has erupted just once in the past 10,000 years, scientists consider it to be active, even if it is in a period of dormancy or currently erupting. The only “safe” volcano is classified as extinct, which means that it is not expected to erupt in the future. Nonetheless, even extinct volcanoes may surprise scientists and they still are prone to mass wasting events.

Scientists usually focus their monitoring efforts on active volcanoes, especially those that might affect populated areas. By documenting the eruption history of active volcanoes, scientists may even be able to construct a broad timeframe in which an eruption is expected.

Earthquakes

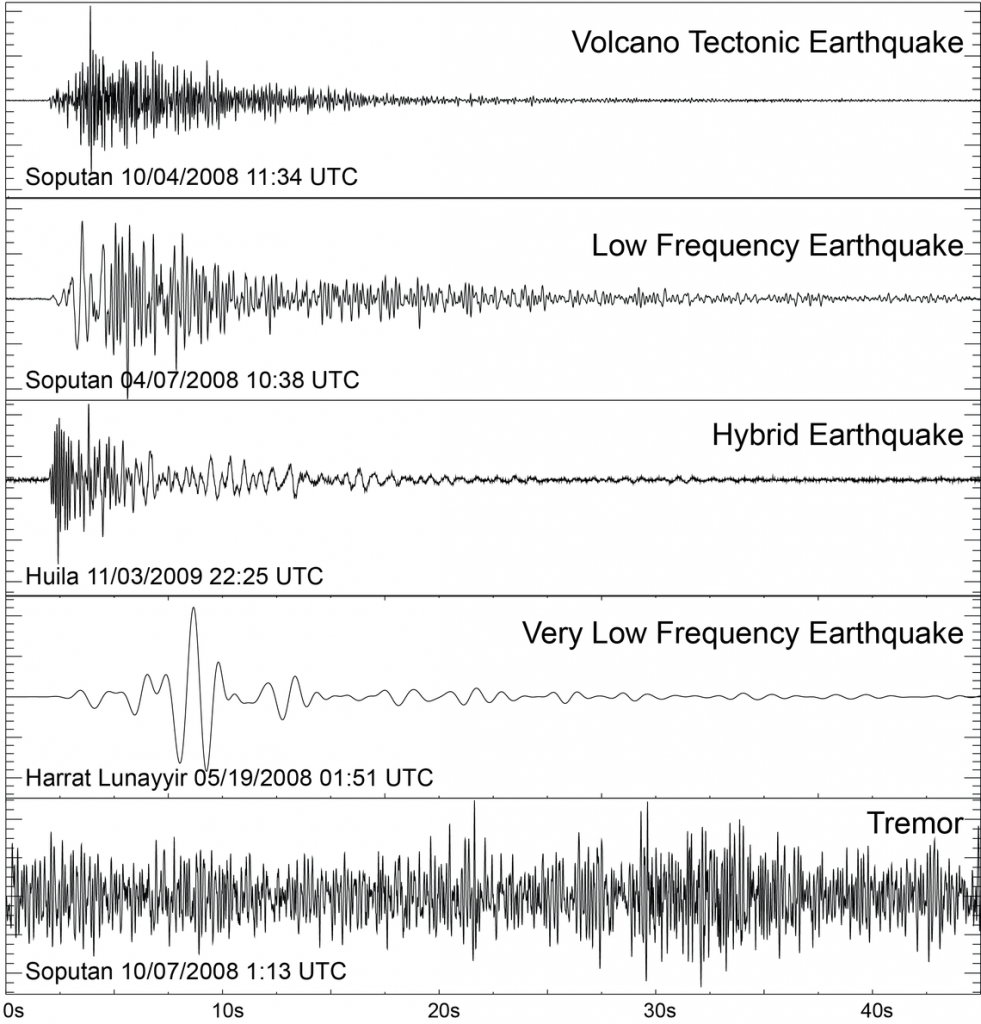

When magma stirs beneath an active volcano, it can shake the ground nearby. The sudden shaking of ground beneath a volcano produces energy in the form of seismic waves, or earthquakes.

A good indicator of a volcano that is just about to erupt is a series or “swarm” of earthquakes. Scientists measure these with instruments called seismographs, which capture the seismic waves released by the movement of the volcanic slope [7].

Ground Deformation

In addition to producing earthquakes, the movement of magma under a volcano can also push and move the flanks of the mountainside. The deformation of the ground along the volcanic slope is not very apparent to the naked eye. Scientists use instruments called tiltmeters, which precisely measure the angle of a volcano’s slope. When that slope starts to deform under pressure from the underlying melted rock and gas, it will change the slope angle of the volcano [8]. This process will even cause mass wasting events.

Some scientists now use the modern technique of remote sensing to detect subtle changes in the volcano’s shape and slope. Modern drones and satellites can be implemented to track small changes in elevation, temperature in areas that are inaccessible to scientists. Some of these technologies include Light Detection and Ranging (Lidar), Global Positioning System stations (GPS), and Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR).

Gas Emissions

Some active volcanoes that are about to erupt release gases ahead of magma. These gases include sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O), and hydrochloric acid (HCl). Scientists will detect these gases near the vent of the volcano or sample them and analyze them later with sophisticated instruments that can measure gas concentration called spectrometers. If certain gases increase in concentration, it may indicate that an eruption is imminent [9].

A hazardous molten rock ejected by volcanic eruptions that is at least more than 2.5 inches in diameter.

an area on the Earth's surface where lava, ash, and/or volatile gases erupt and eventually solidify into rock.

The study and monitoring of volcanoes.

Vibrations and energetic waves produced by the movement within Earth's crust and interior.

A volcano that is not currently erupting but still has the possibility of becoming active.

A volcano that has erupted at least once over the past 10,000 years and has the possibility of erupting in the future.

A volcano that is not currently erupting and is not expected to erupt in the future.

The process in which rock, soil, or sediment moves down a slope under the force of gravity. Mass wasting is an umbrella term that includes hazards such as landslides, debris flows, rock falls, and mudslides.

molten rock that can be found beneath the Earth's surface.

An instrument that measures and records seismic waves caused by geologic activity in the Earth's interior. The graphical product of a seismograph recording is called a seismogram.

An instrument that detects very small changes in movement in the angle of the ground over time.

The technique of mapping, scanning and monitoring physical planetary characteristics using emitted and reflected radiation. This is done using drones, satellites, vessels, or aircraft from a distance.