Learning Objectives

- Identify strategies for improving listening competence at each stage of the listening process.

- Summarize the characteristics of active listening.

- Apply critical-listening skills in interpersonal, educational, and mediated contexts.

- Practice empathetic listening skills.

- Discuss ways to improve listening competence in relational, professional, and cultural contexts.

Many people admit that they could stand to improve their listening skills. This section will help us do that. In this section, we will learn strategies for developing and improving competence at each stage of the listening process. We will also define active listening and the behaviors that go along with it. Looking back to the types of listening discussed earlier, we will learn specific strategies for sharpening our critical and empathetic listening skills. In keeping with our focus on integrative learning, we will also apply the skills we have learned in academic, professional, and relational contexts and explore how culture and gender affect listening.

Listening Competence at Each Stage of the Listening Process

We can develop competence within each stage of the listening process, as the following list indicates (Ridge, 1993):

- To improve listening at the receiving stage,

- prepare yourself to listen,

- discern between intentional messages and noise,

- concentrate on stimuli most relevant to your listening purpose(s) or goal(s),

- be mindful of the selection and attention process as much as possible,

- pay attention to turn-taking signals so you can follow the conversational flow, and

- avoid interrupting someone while they are speaking in order to maintain your ability to receive stimuli and listen.

- To improve listening at the interpreting stage,

- identify main points and supporting points;

- use contextual clues from the person or environment to discern additional meaning;

- be aware of how a relational, cultural, or situational context can influence meaning;

- be aware of the different meanings of silence; and

- note differences in tone of voice and other paralinguistic cues that influence meaning.

- To improve listening at the recalling stage,

- use multiple sensory channels to decode messages and make more complete memories;

- repeat, rephrase, and reorganize information to fit your cognitive preferences; and

- use mnemonic devices as a gimmick to help with recall.

- To improve listening at the evaluating stage,

- separate facts, inferences, and judgments;

- be familiar with and able to identify persuasive strategies and fallacies of reasoning;

- assess the credibility of the speaker and the message; and

- be aware of your own biases and how your perceptual filters can create barriers to effective listening.

- To improve listening at the responding stage,

- ask appropriate clarifying and follow-up questions and paraphrase information to check understanding,

- give feedback that is relevant to the speaker’s purpose/motivation for speaking,

- adapt your response to the speaker and the context, and

- do not let the preparation and rehearsal of your response diminish earlier stages of listening.

Active Listening

Active listening refers to the process of pairing outwardly visible positive listening behaviors with positive cognitive listening practices. Active listening can help address many of the environmental, physical, cognitive, and personal barriers to effective listening that we discussed earlier. The behaviors associated with active listening can also enhance informational, critical, and empathetic listening.

Active Listening Can Help Overcome Barriers to Effective Listening

Being an active listener starts before you actually start receiving a message. Active listeners make strategic choices and take action in order to set up ideal listening conditions. Physical and environmental noises can often be managed by moving locations or by manipulating the lighting, temperature, or furniture. When possible, avoid important listening activities during times of distracting psychological or physiological noise. For example, we often know when we’re going to be hungry, full, more awake, less awake, more anxious, or less anxious, and advance planning can alleviate the presence of these barriers. For college students, who often have some flexibility in their class schedules, knowing when you best listen can help you make strategic choices regarding what class to take when. And student options are increasing, as some colleges are offering classes in the overnight hours to accommodate working students and students who are just “night owls” (Toppo, 2011). Of course, we don’t always have control over our schedule, in which case we will need to utilize other effective listening strategies that we will learn more about later in this chapter.

In terms of cognitive barriers to effective listening, we can prime ourselves to listen by analyzing a listening situation before it begins. For example, you could ask yourself the following questions:

- “What are my goals for listening to this message?”

- “How does this message relate to me / affect my life?”

- “What listening type and style are most appropriate for this message?”

As we learned earlier, the difference between speech and thought processing rate means listeners’ level of attention varies while receiving a message. Effective listeners must work to maintain focus as much as possible and refocus when attention shifts or fades (Wolvin & Coakley, 1993). One way to do this is to find the motivation to listen. If you can identify intrinsic and or extrinsic motivations for listening to a particular message, then you will be more likely to remember the information presented. Ask yourself how a message could impact your life, your career, your intellect, or your relationships. This can help overcome our tendency toward selective attention. As senders of messages, we can help listeners by making the relevance of what we’re saying clear and offering well-organized messages that are tailored for our listeners. We will learn much more about establishing relevance, organizing a message, and gaining the attention of an audience in public speaking contexts later in the book.

Given that we can process more words per minute than people can speak, we can engage in internal dialogue, making good use of our intrapersonal communication, to become a better listener. Three possibilities for internal dialogue include covert coaching, self-reinforcement, and covert questioning; explanations and examples of each follow (Hargie, 2011):

- Covert coaching involves sending yourself messages containing advice about better listening, such as “You’re getting distracted by things you have to do after work. Just focus on what your supervisor is saying now.”

- Self-reinforcement involves sending yourself affirmative and positive messages: “You’re being a good active listener. This will help you do well on the next exam.”

- Covert questioning involves asking yourself questions about the content in ways that focus your attention and reinforce the material: “What is the main idea from that PowerPoint slide?” “Why is he talking about his brother in front of our neighbors?”

Internal dialogue is a more structured way to engage in active listening, but we can use more general approaches as well. I suggest that students occupy the “extra” channels in their mind with thoughts that are related to the primary message being received instead of thoughts that are unrelated. We can use those channels to resort, rephrase, and repeat what a speaker says. When we resort, we can help mentally repair disorganized messages. When we rephrase, we can put messages into our own words in ways that better fit our cognitive preferences. When we repeat, we can help messages transfer from short-term to long-term memory.

Other tools can help with concentration and memory. Mental bracketing refers to the process of intentionally separating out intrusive or irrelevant thoughts that may distract you from listening (McCornack, 2007). This requires that we monitor our concentration and attention and be prepared to let thoughts that aren’t related to a speaker’s message pass through our minds without us giving them much attention. Mnemonic devices are techniques that can aid in information recall (Hargie 2011). Starting in ancient Greece and Rome, educators used these devices to help people remember information. They work by imposing order and organization on information. Three main mnemonic devices are acronyms, rhymes, and visualization, and examples of each follow:

- Acronyms. HOMES—to help remember the Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior).

- Rhyme. “Righty tighty, lefty loosey”—to remember which way most light bulbs, screws, and other coupling devices turn to make them go in or out.

- Visualization. Imagine seeing a glass of port wine (which is red) and the red navigation light on a boat to help remember that the red light on a boat is always on the port side, which will also help you remember that the blue light must be on the starboard side.

Active Listening Behaviors

From the suggestions discussed previously, you can see that we can prepare for active listening in advance and engage in certain cognitive strategies to help us listen better. We also engage in active listening behaviors as we receive and process messages.

Eye contact is a key sign of active listening. Speakers usually interpret a listener’s eye contact as a signal of attentiveness. While a lack of eye contact may indicate inattentiveness, it can also signal cognitive processing. When we look away to process new information, we usually do it unconsciously. Be aware, however, that your conversational partner may interpret this as not listening. If you really do need to take a moment to think about something, you could indicate that to the other person by saying, “That’s new information to me. Give me just a second to think through it.” We already learned the role that back-channel cues play in listening. An occasional head nod and “uh-huh” signal that you are paying attention. However, when we give these cues as a form of “autopilot” listening, others can usually tell that we are pseudo-listening, and whether they call us on it or not, that impression could lead to negative judgments.

A more direct way to indicate active listening is to reference previous statements made by the speaker. Norms of politeness usually call on us to reference a past statement or connect to the speaker’s current thought before starting a conversational turn. Being able to summarize what someone said to ensure that the topic has been satisfactorily covered and understood or being able to segue in such a way that validates what the previous speaker said helps regulate conversational flow. Asking probing questions is another way to directly indicate listening and to keep a conversation going, since they encourage and invite a person to speak more. You can also ask questions that seek clarification and not just elaboration. Speakers should present complex information at a slower speaking rate than familiar information, but many will not. Remember that your nonverbal feedback can be useful for a speaker, as it signals that you are listening but also whether or not you understand. If a speaker fails to read your nonverbal feedback, you may need to follow up with verbal communication in the form of paraphrased messages and clarifying questions.

As active listeners, we want to be excited and engaged, but don’t let excitement manifest itself in interruptions. Being an active listener means knowing when to maintain our role as listener and resist the urge to take a conversational turn. Research shows that people with higher social status are more likely to interrupt others, so keep this in mind and be prepared for it if you are speaking to a high-status person, or try to resist it if you are the high-status person in an interaction (Hargie, 2011).

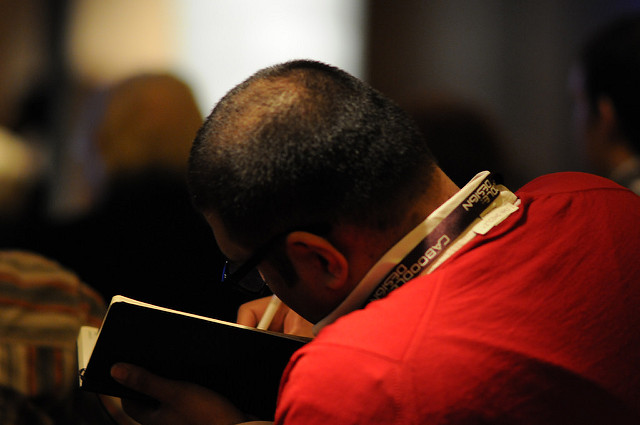

Good note-taking skills allow listeners to stay engaged with a message and aid in recall of information.

Steven Lilley – Note taking – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Note-taking can also indicate active listening. Translating information through writing into our own cognitive structures and schemata allows us to better interpret and assimilate information. Of course, note-taking isn’t always a viable option. It would be fairly awkward to take notes during a first date or a casual exchange between new coworkers. But in some situations where we wouldn’t normally consider taking notes, a little awkwardness might be worth it for the sake of understanding and recalling the information. For example, many people don’t think about taking notes when getting information from their doctor or banker. I actually invite students to take notes during informal meetings because I think they sometimes don’t think about it or don’t think it’s appropriate. But many people would rather someone jot down notes instead of having to respond to follow-up questions on information that was already clearly conveyed. To help facilitate your note-taking, you might say something like “Do you mind if I jot down some notes? This seems important.”

In summary, active listening is exhibited through verbal and nonverbal cues, including steady eye contact with the speaker; smiling; slightly raised eyebrows; upright posture; body position that is leaned in toward the speaker; nonverbal back-channel cues such as head nods; verbal back-channel cues such as “OK,” “mmhum,” or “oh”; and a lack of distracting mannerisms like doodling or fidgeting (Hargie, 2011).

“Getting Competent”

Listening in the Classroom

The following statistic illustrates the importance of listening in academic contexts: four hundred first-year students were given a listening test before they started classes. At the end of that year, 49 percent of the students with low scores were on academic probation, while only 4 percent of those who scored high were (Conaway, 1982). Listening effectively isn’t something that just happens; it takes work on the part of students and teachers. One of the most difficult challenges for teachers is eliciting good listening behaviors from their students, and the method of instruction teachers use affects how a student will listen and learn (Beall et al., 2008). Given that there are different learning styles, we know that to be effective, teachers may have to find some way to appeal to each learning style. Although teachers often make this attempt, it is also not realistic or practical to think that this practice can be used all the time. Therefore, students should also think of ways they can improve their listening competence, because listening is an active process that we can exert some control over. The following tips will help you listen more effectively in the classroom:

- Be prepared to process challenging messages. You can use the internal dialogue strategy we discussed earlier to “mentally repair” messages that you receive to make them more listenable (Rubin, 1993). For example, you might say, “It seems like we’ve moved on to a different main point now. See if you can pull out the subpoints to help stay on track.”

- Act like a good listener. While I’m not advocating that you engage in pseudo-listening, engaging in active listening behaviors can help you listen better when you are having difficulty concentrating or finding motivation to listen. Make eye contact with the instructor and give appropriate nonverbal feedback. Students often take notes only when directed to by the instructor or when there is an explicit reason to do so (e.g., to recall information for an exam or some other purpose). Since you never know what information you may want to recall later, take notes even when it’s not required that you do so. As a caveat, however, do not try to transcribe everything your instructor says or includes on a PowerPoint, because you will likely miss information related to main ideas that is more important than minor details. Instead, listen for main ideas.

- Figure out from where the instructor most frequently speaks and sit close to that area. Being able to make eye contact with an instructor facilitates listening, increases rapport, allows students to benefit more from immediacy behaviors, and minimizes distractions since the instructor is the primary stimulus within the student’s field of vision.

- Figure out your preferred learning style and adopt listening strategies that complement it.

- Let your instructor know when you don’t understand something. Instead of giving a quizzical look that says “What?” or pretending you know what’s going on, let your instructor know when you don’t understand something. Instead of asking the instructor to simply repeat something, ask her or him to rephrase it or provide an example. When you ask questions, ask specific clarifying questions that request a definition, an explanation, or an elaboration.

- What are some listening challenges that you face in the classroom? What can you do to overcome them?

- Take the Learning Styles Inventory survey at the following link to determine what your primary learning style is: http://www.personal.psu.edu/bxb11/LSI/LSI.htm. Do some research to identify specific listening/studying strategies that work well for your learning style.

Becoming a Better Critical Listener

Critical listening involves evaluating the credibility, completeness, and worth of a speaker’s message. Some listening scholars note that critical listening represents the deepest level of listening (Floyd, 1985). Critical listening is also important in a democracy that values free speech. The US Constitution grants US citizens the right to free speech, and many people duly protect that right for you and me. Since people can say just about anything they want, we are surrounded by countless messages that vary tremendously in terms of their value, degree of ethics, accuracy, and quality. Therefore it falls on us to responsibly and critically evaluate the messages we receive. Some messages are produced by people who are intentionally misleading, ill informed, or motivated by the potential for personal gain, but such messages can be received as honest, credible, or altruistic even though they aren’t. Being able to critically evaluate messages helps us have more control over and awareness of the influence such people may have on us. In order to critically evaluate messages, we must enhance our critical-listening skills.

Some critical-listening skills include distinguishing between facts and inferences, evaluating supporting evidence, discovering your own biases, and listening beyond the message. Chapter 3 “Verbal Communication” noted that part of being an ethical communicator is being accountable for what we say by distinguishing between facts and inferences (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). This is an ideal that is not always met in practice, so a critical listener should also make these distinctions, since the speaker may not. Since facts are widely agreed-on conclusions, they can be verified as such through some extra research. Take care in your research to note the context from which the fact emerged, as speakers may take a statistic or quote out of context, distorting its meaning. Inferences are not as easy to evaluate, because they are based on unverifiable thoughts of a speaker or on speculation. Inferences are usually based at least partially on something that is known, so it is possible to evaluate whether an inference was made carefully or not. In this sense, you may evaluate an inference based on several known facts as more credible than an inference based on one fact and more speculation. Asking a question like “What led you to think this?” is a good way to get information needed to evaluate the strength of an inference.

Distinguishing among facts and inferences and evaluating the credibility of supporting material are critical-listening skills that also require good informational-listening skills. In more formal speaking situations, speakers may cite published or publicly available sources to support their messages. When speakers verbally cite their sources, you can use the credibility of the source to help evaluate the credibility of the speaker’s message. For example, a national newspaper would likely be more credible on a major national event than a tabloid magazine or an anonymous blog. In regular interactions, people also have sources for their information but are not as likely to note them within their message. Asking questions like “Where’d you hear that?” or “How do you know that?” can help get information needed to make critical evaluations. You can look to Chapter 11 “Informative and Persuasive Speaking” to learn much more about persuasive strategies and how to evaluate the strength of arguments.

Discovering your own biases can help you recognize when they interfere with your ability to fully process a message. Unfortunately, most people aren’t asked to critically reflect on their identities and their perspectives unless they are in college, and even people who were once critically reflective in college or elsewhere may no longer be so. Biases are also difficult to discover, because we don’t see them as biases; we see them as normal or “the way things are.” Asking yourself “What led you to think this?” and “How do you know that?” can be a good start toward acknowledging your biases. We will also learn more about self-reflection and critical thinking in Chapter 8 “Culture and Communication”.

Last, to be a better critical listener, think beyond the message. A good critical listener asks the following questions: What is being said and what is not being said? In whose interests are these claims being made? Whose voices/ideas are included and excluded? These questions take into account that speakers intentionally and unintentionally slant, edit, or twist messages to make them fit particular perspectives or for personal gain. Also ask yourself questions like “What are the speaker’s goals?” You can also rephrase that question and direct it toward the speaker, asking them, “What is your goal in this interaction?” When you feel yourself nearing an evaluation or conclusion, pause and ask yourself what influenced you. Although we like to think that we are most often persuaded through logical evidence and reasoning, we are susceptible to persuasive shortcuts that rely on the credibility or likability of a speaker or on our emotions rather than the strength of his or her evidence (Petty & Cacioppo, 1984). So keep a check on your emotional involvement to be aware of how it may be influencing your evaluation. Also, be aware that how likable, attractive, or friendly you think a person is may also lead you to more positively evaluate his or her messages.

Other Tips to Help You Become a Better Critical Listener

- Ask questions to help get more information and increase your critical awareness when you get answers like “Because that’s the way things are,” “It’s always been like that,” “I don’t know; I just don’t like it,” “Everyone believes that,” or “It’s just natural/normal.” These are not really answers that are useful in your critical evaluation and may be an indication that speakers don’t really know why they reached the conclusion they did or that they reached it without much critical thinking on their part.

- Be especially critical of speakers who set up “either/or” options, because they artificially limit an issue or situation to two options when there are always more. Also be aware of people who overgeneralize, especially when those generalizations are based on stereotypical or prejudiced views. For example, the world is not just Republican or Democrat, male or female, pro-life or pro-choice, or Christian or atheist.

- Evaluate the speaker’s message instead of his or her appearance, personality, or other characteristics. Unless someone’s appearance, personality, or behavior is relevant to an interaction, direct your criticism to the message.

- Be aware that critical evaluation isn’t always quick or easy. Sometimes you may have to withhold judgment because your evaluation will take more time. Also keep in mind your evaluation may not be final, and you should be open to critical reflection and possible revision later.

- Avoid mind reading, which is assuming you know what the other person is going to say or that you know why they reached the conclusion they did. This leads to jumping to conclusions, which shortcuts the critical evaluation process.

“Getting Critical”

Critical Listening and Political Spin

In just the past twenty years, the rise of political fact checking occurred as a result of the increasingly sophisticated rhetoric of politicians and their representatives (Dobbs, 2012). As political campaigns began to adopt communication strategies employed by advertising agencies and public relations firms, their messages became more ambiguous, unclear, and sometimes outright misleading. While there are numerous political fact-checking sources now to which citizens can turn for an analysis of political messages, it is important that we are able to use our own critical-listening skills to see through some of the political spin that now characterizes politics in the United States.

Since we get most of our political messages through the media rather than directly from a politician, the media is a logical place to turn for guidance on fact checking. Unfortunately, the media is often manipulated by political communication strategies as well (Dobbs, 2012). Sometimes media outlets transmit messages even though a critical evaluation of the message shows that it lacks credibility, completeness, or worth. Journalists who engage in political fact checking have been criticized for putting their subjective viewpoints into what is supposed to be objective news coverage. These journalists have fought back against what they call the norm of “false equivalence.” One view of journalism sees the reporter as an objective conveyer of political messages. This could be described as the “We report; you decide” brand of journalism. Other reporters see themselves as “truth seekers.” In this sense, the journalists engage in some critical listening and evaluation on the part of the citizen, who may not have the time or ability to do so.

Michael Dobbs, who started the political fact-checking program at the Washington Post, says, “Fairness is preserved not by treating all sides of an argument equally, but through an independent, open-minded approach to the evidence” (Dobbs, 2012). He also notes that outright lies are much less common in politics than are exaggeration, spin, and insinuation. This fact puts much of political discourse into an ethical gray area that can be especially difficult for even professional fact checkers to evaluate. Instead of simple “true/false” categories, fact checkers like the Washington Post issue evaluations such as “Half true, mostly true, half-flip, or full-flop” to political statements. Although we all don’t have the time and resources to fact check all the political statements we hear, it may be worth employing some of the strategies used by these professional fact checkers on issues that are very important to us or have major implications for others. Some fact-checking resources include http://www.PolitiFact.com, http://www.factcheck.org, and http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker. The caution here for any critical listener is to be aware of our tendency to gravitate toward messages with which we agree and avoid or automatically reject messages with which we disagree. In short, it’s often easier for us to critically evaluate the messages of politicians with whom we disagree and uncritically accept messages from those with whom we agree. Exploring the fact-check websites above can help expose ourselves to critical evaluation that we might not otherwise encounter.

- One school of thought in journalism says it’s up to the reporters to convey information as it is presented and then up to the viewer/reader to evaluate the message. The other school of thought says that the reporter should investigate and evaluate claims made by those on all sides of an issue equally and share their findings with viewers/readers. Which approach do you think is better and why?

- In the lead-up to the war in Iraq, journalists and news outlets did not critically evaluate claims from the Bush administration that there was clear evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Many now cite this as an instance of failed fact checking that had global repercussions. Visit one of the fact-checking resources mentioned previously to find other examples of fact checking that exposed manipulated messages. To enhance your critical thinking, find one example that critiques a viewpoint, politician, or political party that you typically agree with and one that you disagree with. Discuss what you learned from the examples you found.

Becoming a Better Empathetic Listener

A prominent scholar of empathetic listening describes it this way: “Empathetic listening is to be respectful of the dignity of others. Empathetic listening is a caring, a love of the wisdom to be found in others whoever they may be” (Bruneau, 1993). This quote conveys that empathetic listening is more philosophical than the other types of listening. It requires that we are open to subjectivity and that we engage in it because we genuinely see it as worthwhile.

Combining active and empathetic listening leads to active-empathetic listening. During active-empathetic listening a listener becomes actively and emotionally involved in an interaction in such a way that it is conscious on the part of the listener and perceived by the speaker (Bodie, 2011). To be a better empathetic listener, we need to suspend or at least attempt to suppress our judgment of the other person or their message so we can fully attend to both. Paraphrasing is an important part of empathetic listening, because it helps us put the other person’s words into our frame of experience without making it about us. In addition, speaking the words of someone else in our own way can help evoke within us the feelings that the other person felt while saying them (Bodie, 2011). Active-empathetic listening is more than echoing back verbal messages. We can also engage in mirroring, which refers to a listener’s replication of the nonverbal signals of a speaker (Bruneau, 1993). Therapists, for example, are often taught to adopt a posture and tone similar to their patients in order to build rapport and project empathy.

Empathetic listeners should not steal the spotlight from the speaker. Offer support without offering your own story or advice.

Blondinrikard Froberg – Spotlight – CC BY 2.0.

Paraphrasing and questioning are useful techniques for empathetic listening because they allow us to respond to a speaker without taking “the floor,” or the attention, away for long. Specifically, questions that ask for elaboration act as “verbal door openers,” and inviting someone to speak more and then validating their speech through active listening cues can help a person feel “listened to” (Hargie, 2011). I’ve found that paraphrasing and asking questions are also useful when we feel tempted to share our own stories and experiences rather than maintaining our listening role. These questions aren’t intended to solicit more information, so we can guide or direct the speaker toward a specific course of action. Although it is easier for us to slip into an advisory mode—saying things like “Well if I were you, I would…”—we have to resist the temptation to give unsolicited advice.

Empathetic listening can be worthwhile, but it also brings challenges. In terms of costs, empathetic listening can use up time and effort. Since this type of listening can’t be contained within a proscribed time frame, it may be especially difficult for time-oriented listeners (Bruneau, 1993). Empathetic listening can also be a test of our endurance, as its orientation toward and focus on supporting the other requires the processing and integration of much verbal and nonverbal information. Because of this potential strain, it’s important to know your limits as an empathetic listener. While listening can be therapeutic, it is not appropriate for people without training and preparation to try to serve as a therapist. Some people have chronic issues that necessitate professional listening for the purposes of evaluation, diagnosis, and therapy. Lending an ear is different from diagnosing and treating. If you have a friend who is exhibiting signs of a more serious issue that needs attention, listen to the extent that you feel comfortable and then be prepared to provide referrals to other resources that have training to help. To face these challenges, good empathetic listeners typically have a generally positive self-concept and self-esteem, are nonverbally sensitive and expressive, and are comfortable with embracing another person’s subjectivity and refraining from too much analytic thought.

Becoming a Better Contextual Listener

Active, critical, and empathetic listening skills can be helpful in a variety of contexts. Understanding the role that listening plays in professional, relational, cultural, and gendered contexts can help us more competently apply these skills. Whether we are listening to or evaluating messages from a supervisor, parent, or intercultural conversational partner, we have much to gain or lose based on our ability to apply listening skills and knowledge in various contexts.

Listening in Professional Contexts

Listening and organizational-communication scholars note that listening is one of the most neglected aspects of organizational-communication research (Flynn, Valikoski, & Grau, 2008). Aside from a lack of research, a study also found that business schools lack curriculum that includes instruction and/or training in communication skills like listening in their master of business administration (MBA) programs (Alsop, 2002). This lack of a focus on listening persists, even though we know that more effective listening skills have been shown to enhance sales performance and that managers who exhibit good listening skills help create open communication climates that can lead to increased feelings of supportiveness, motivation, and productivity (Flynn, Valikoski, & Grau, 2008). Specifically, empathetic listening and active listening can play key roles in organizational communication. Managers are wise to enhance their empathetic listening skills, as being able to empathize with employees contributes to a positive communication climate. Active listening among organizational members also promotes involvement and increases motivation, which leads to more cohesion and enhances the communication climate.

Organizational scholars have examined various communication climates specific to listening. Listening environment refers to characteristics and norms of an organization and its members that contribute to expectations for and perceptions about listening (Brownell, 1993). Positive listening environments are perceived to be more employee centered, which can improve job satisfaction and cohesion. But how do we create such environments?

Positive listening environments are facilitated by the breaking down of barriers to concentration, the reduction of noise, the creation of a shared reality (through shared language, such as similar jargon or a shared vision statement), intentional spaces that promote listening, official opportunities that promote listening, training in listening for all employees, and leaders who model good listening practices and praise others who are successful listeners (Brownell, 1993). Policies and practices that support listening must go hand in hand. After all, what does an “open-door” policy mean if it is not coupled with actions that demonstrate the sincerity of the policy?

“Getting Real”

Becoming a “Listening Leader”

Dr. Rick Bommelje has popularized the concept of the “listening leader” (Listen-Coach.com, 2012). As a listening coach, he offers training and resources to help people in various career paths increase their listening competence. For people who are very committed to increasing their listening skills, the International Listening Association has now endorsed a program to become a Certified Listening Professional (CLP), which entails advanced independent study, close work with a listening mentor, and the completion of a written exam.[1] There are also training programs to help with empathetic listening that are offered through the Compassionate Listening Project.[2] These programs evidence the growing focus on the importance of listening in all professional contexts.

Scholarly research has consistently shown that listening ability is a key part of leadership in professional contexts and competence in listening aids in decision making. A survey sent to hundreds of companies in the United States found that poor listening skills create problems at all levels of an organizational hierarchy, ranging from entry-level positions to CEOs (Hargie, 2011). Leaders such as managers, team coaches, department heads, and executives must be versatile in terms of listening type and style in order to adapt to the diverse listening needs of employees, clients/customers, colleagues, and other stakeholders.

Even if we don’t have the time or money to invest in one of these professional-listening training programs, we can draw inspiration from the goal of becoming a listening leader. By reading this book, you are already taking an important step toward improving a variety of communication competencies, including listening, and you can always take it upon yourself to further your study and increase your skills in a particular area to better prepare yourself to create positive communication climates and listening environments. You can also use these skills to make yourself a more desirable employee.

- Make a list of the behaviors that you think a listening leader would exhibit. Which of these do you think you do well? Which do you need to work on?

- What do you think has contributed to the perceived shortage of listening skills in professional contexts?

- Given your personal career goals, what listening skills do you think you will need to possess and employ in order to be successful?

Listening in Relational Contexts

Listening plays a central role in establishing and maintaining our relationships (Nelson-Jones, 2006). Without some listening competence, we wouldn’t be able to engage in the self-disclosure process, which is essential for the establishment of relationships. Newly acquainted people get to know each other through increasingly personal and reciprocal disclosures of personal information. In order to reciprocate a conversational partner’s disclosure, we must process it through listening. Once relationships are formed, listening to others provides a psychological reward, through the simple act of recognition, that helps maintain our relationships. Listening to our relational partners and being listened to in return is part of the give-and-take of any interpersonal relationship. Our thoughts and experiences “back up” inside of us, and getting them out helps us maintain a positive balance (Nelson, Jones, 2006). So something as routine and seemingly pointless as listening to our romantic partner debrief the events of his or her day or our roommate recount his or her weekend back home shows that we are taking an interest in their lives and are willing to put our own needs and concerns aside for a moment to attend to their needs. Listening also closely ties to conflict, as a lack of listening often plays a large role in creating conflict, while effective listening helps us resolve it.

Listening has relational implications throughout our lives, too. Parents who engage in competent listening behaviors with their children from a very young age make their children feel worthwhile and appreciated, which affects their development in terms of personality and character (Nichols, 1995).

Parents who exhibit competent listening behaviors toward their children provide them with a sense of recognition and security that affects their future development.

Madhavi Kuram – Listen to your kids – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

A lack of listening leads to feelings of loneliness, which results in lower self-esteem and higher degrees of anxiety. In fact, by the age of four or five years old, the empathy and recognition shown by the presence or lack of listening has molded children’s personalities in noticeable ways (Nichols, 1995). Children who have been listened to grow up expecting that others will be available and receptive to them. These children are therefore more likely to interact confidently with teachers, parents, and peers in ways that help develop communication competence that will be built on throughout their lives. Children who have not been listened to may come to expect that others will not want to listen to them, which leads to a lack of opportunities to practice, develop, and hone foundational communication skills. Fortunately for the more-listened-to children and unfortunately for the less-listened-to children, these early experiences become predispositions that don’t change much as the children get older and may actually reinforce themselves and become stronger.

Listening and Culture

Some cultures place more importance on listening than other cultures. In general, collectivistic cultures tend to value listening more than individualistic cultures that are more speaker oriented. The value placed on verbal and nonverbal meaning also varies by culture and influences how we communicate and listen. A low-context communication style is one in which much of the meaning generated within an interaction comes from the verbal communication used rather than nonverbal or contextual cues. Conversely, much of the meaning generated by a high-context communication style comes from nonverbal and contextual cues (Lustig & Koester, 2006). For example, US Americans of European descent generally use a low-context communication style, while people in East Asian and Latin American cultures use a high-context communication style.

Contextual communication styles affect listening in many ways. Cultures with a high-context orientation generally use less verbal communication and value silence as a form of communication, which requires listeners to pay close attention to nonverbal signals and consider contextual influences on a message. Cultures with a low-context orientation must use more verbal communication and provide explicit details, since listeners aren’t expected to derive meaning from the context. Note that people from low-context cultures may feel frustrated by the ambiguity of speakers from high-context cultures, while speakers from high-context cultures may feel overwhelmed or even insulted by the level of detail used by low-context communicators. Cultures with a low-context communication style also tend to have a monochronic orientation toward time, while high-context cultures have a polychronic time orientation, which also affects listening.

As Chapter 8 “Culture and Communication” discusses, cultures that favor a structured and commodified orientation toward time are said to be monochronic, while cultures that favor a more flexible orientation are polychronic. Monochronic cultures like the United States value time and action-oriented listening styles, especially in professional contexts, because time is seen as a commodity that is scarce and must be managed (McCorncack, 2007). This is evidenced by leaders in businesses and organizations who often request “executive summaries” that only focus on the most relevant information and who use statements like “Get to the point.” Polychronic cultures value people and content-oriented listening styles, which makes sense when we consider that polychronic cultures also tend to be more collectivistic and use a high-context communication style. In collectivistic cultures, indirect communication is preferred in cases where direct communication would be considered a threat to the other person’s face (desired public image). For example, flatly turning down a business offer would be too direct, so a person might reply with a “maybe” instead of a “no.” The person making the proposal, however, would be able to draw on contextual clues that they implicitly learned through socialization to interpret the “maybe” as a “no.”

Listening and Gender

Research on gender and listening has produced mixed results. As we’ve already learned, much of the research on gender differences and communication has been influenced by gender stereotypes and falsely connected to biological differences. More recent research has found that people communicate in ways that conform to gender stereotypes in some situations and not in others, which shows that our communication is more influenced by societal expectations than by innate or gendered “hard-wiring.” For example, through socialization, men are generally discouraged from expressing emotions in public. A woman sharing an emotional experience with a man may perceive the man’s lack of emotional reaction as a sign of inattentiveness, especially if he typically shows more emotion during private interactions. The man, however, may be listening but withholding nonverbal expressiveness because of social norms. He may not realize that withholding those expressions could be seen as a lack of empathetic or active listening. Researchers also dispelled the belief that men interrupt more than women do, finding that men and women interrupt each other with similar frequency in cross-gender encounters (Dindia, 1987). So men may interrupt each other more in same-gender interactions as a conscious or subconscious attempt to establish dominance because such behaviors are expected, as men are generally socialized to be more competitive than women. However, this type of competitive interrupting isn’t as present in cross-gender interactions because the contexts have shifted.

Key Takeaways

- You can improve listening competence at the receiving stage by preparing yourself to listen and distinguishing between intentional messages and noise; at the interpreting stage by identifying main points and supporting points and taking multiple contexts into consideration; at the recalling stage by creating memories using multiple senses and repeating, rephrasing, and reorganizing messages to fit cognitive preferences; at the evaluating stage by separating facts from inferences and assessing the credibility of the speaker’s message; and at the responding stage by asking appropriate questions, offering paraphrased messages, and adapting your response to the speaker and the situation.

- Active listening is the process of pairing outwardly visible positive listening behaviors with positive cognitive listening practices and is characterized by mentally preparing yourself to listen, working to maintain focus on concentration, using appropriate verbal and nonverbal back-channel cues to signal attentiveness, and engaging in strategies like note taking and mentally reorganizing information to help with recall.

- In order to apply critical-listening skills in multiple contexts, we must be able to distinguish between facts and inferences, evaluate a speaker’s supporting evidence, discover our own biases, and think beyond the message.

- In order to practice empathetic listening skills, we must be able to support others’ subjective experience; temporarily set aside our own needs to focus on the other person; encourage elaboration through active listening and questioning; avoid the temptation to tell our own stories and/or give advice; effectively mirror the nonverbal communication of others; and acknowledge our limits as empathetic listeners.

-

Getting integrated: Different listening strategies may need to be applied in different listening contexts.

- In professional contexts, listening is considered a necessary skill, but most people do not receive explicit instruction in listening. Members of an organization should consciously create a listening environment that promotes and rewards competent listening behaviors.

- In relational contexts, listening plays a central role in initiating relationships, as listening is required for mutual self-disclosure, and in maintaining relationships, as listening to our relational partners provides a psychological reward in the form of recognition. When people aren’t or don’t feel listened to, they may experience feelings of isolation or loneliness that can have negative effects throughout their lives.

- In cultural contexts, high- or low-context communication styles, monochronic or polychronic orientations toward time, and individualistic or collectivistic cultural values affect listening preferences and behaviors.

- Research regarding listening preferences and behaviors of men and women has been contradictory. While some differences in listening exist, many of them are based more on societal expectations for how men and women should listen rather than biological differences.

Exercises

- Keep a “listening log” for part of your day. Note times when you feel like you exhibited competent listening behaviors and note times when listening became challenging. Analyze the log based on what you have learned in this section. Which positive listening skills helped you listen? What strategies could you apply to your listening challenges to improve your listening competence?

- Apply the strategies for effective critical listening to a political message (a search for “political speech” or “partisan speech” on YouTube should provide you with many options). As you analyze the speech, make sure to distinguish between facts and inferences, evaluate a speaker’s supporting evidence, discuss how your own biases may influence your evaluation, and think beyond the message.

- Discuss and analyze the listening environment of a place you have worked or an organization with which you were involved. Overall, was it positive or negative? What were the norms and expectations for effective listening that contributed to the listening environment? Who helped set the tone for the listening environment?

References

Alsop, R., Wall Street Journal-Eastern Edition 240, no. 49 (2002): R4.

Beall, M. L., et al., “State of the Context: Listening in Education,” The International Journal of Listening 22 (2008): 124.

Bodie, G. D., “The Active-Empathetic Listening Scale (AELS): Conceptualization and Evidence of Validity within the Interpersonal Domain,” Communication Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2011): 278.

Brownell, J., “Listening Environment: A Perspective,” in Perspectives on Listening, eds. Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation, 1993), 243.

Bruneau, T., “Empathy and Listening,” in Perspectives on Listening, eds. Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation, 1993), 194.

Conaway, M. S., “Listening: Learning Tool and Retention Agent,” in Improving Reading and Study Skills, eds. Anne S. Algier and Keith W. Algier (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1982).

Dindia, K., “The Effect of Sex of Subject and Sex of Partner on Interruptions,” Human Communication Research 13, no. 3 (1987): 345–71.

Dobbs, M., “The Rise of Political Fact-Checking,” New America Foundation (2012): 1.

Floyd, J. J.,Listening, a Practical Approach (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1985), 39–40.

Flynn, J., Tuula-Riitta Valikoski, and Jennie Grau, “Listening in the Business Context: Reviewing the State of Research,” The International Journal of Listening 22 (2008): 143.

Hargie, O., Skilled Interpersonal Interaction: Research, Theory, and Practice (London: Routledge, 2011), 193.

Hayakawa, S. I. and Alan R. Hayakawa, Language in Thought and Action, 5th ed. (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace, 1990), 22–32.

Listen-Coach.com, Dr. Rick Listen-Coach, accessed July 13, 2012, http://www.listen-coach.com.

Lustig, M. W. and Jolene Koester, Intercultural Competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures, 5th ed. (Boston, MA: Pearson Education, 2006), 110–14.

McCornack, S., Reflect and Relate: An Introduction to Interpersonal Communication (Boston, MA: Bedford/St Martin’s, 2007), 192.

Nelson-Jones, R., Human Relationship Skills, 4th ed. (East Sussex: Routledge, 2006), 37–38.

Nichols, M. P., The Lost Art of Listening (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1995), 25.

Petty, R. E. and John T. Cacioppo, “The Effects of Involvement on Responses to Argument Quantity and Quality: Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46, no. 1 (1984): 69–81.

Ridge, A., “A Perspective of Listening Skills,” in Perspectives on Listening, eds. Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation, 1993), 5–6.

Rubin, D. L., “Listenability = Oral-Based Discourse + Considerateness,” in Perspectives on Listening, eds. Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation, 1993), 277.

Toppo, G., “Colleges Start Offering ‘Midnight Classes’ for Offbeat Needs,” USA Today, October 27, 2011, accessed July 13, 2012, http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/story/2011–10–26/college-midnight-classes/50937996/1.

Wolvin, A. D. and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley, “A Listening Taxonomy,” in Perspectives on Listening, eds. Andrew D. Wolvin and Carolyn Gwynn Coakley (Norwood, NJ: Alex Publishing Corporation, 1993), 19.

- “CLP Training Program,” International Listening Assocation, accessed July 13, 2012, http://www.listen.org/CLPFAQs. ↵

- “Training,” The Compassionate Listening Project, accessed July 13, 2012, http://www.compassionatelistening.org/trainings. ↵