14 Poetic Forms

Classical Poetic Categories

The three classical categorical distinctions held until the 18th-century were Lyric, Narrative, and Dramatic poetry. They derive from Aristotle (who used the word “epic” rather than “narrative”). From the 19th-century on, they have lost categorical force. However, we can still find value in understanding their characteristics as genres.

Lyric: Lyric poetry is a genre that, unlike epic and dramatic poetry, does not attempt to tell a story but instead is of a more personal nature. Poems in this genre tend to be shorter, melodic, and contemplative. Rather than depicting characters and actions, it portrays the poet’s own feelings, states of mind, and perceptions. Originally these were poems intended to be recited or sung to the accompaniment of a lyre.

Narrative/Epic: This genre is often defined as lengthy poems concerning events of a heroic or important nature to the culture of the time. It recounts, in a continuous narrative, the life and works of a heroic or mythological person or group of persons. What had been the stuff of narrative poetry has become the purview of novels and prose fiction more often now.

Dramatic: Dramatic poetry is drama written in verse to be spoken or sung, and appears in varying, sometimes related forms in many cultures.

This categorization of types held from the time of Aristotle (4th C. BCE) until the 18th century. Most poetry of the last two centuries, however, is written in the lyric mode. “Dramatic” and “Narrative” modes have been taken over by prose fiction and film/television.

Two Ways of Thinking about Form

Closed form poetry did not just dominate poetry from its origin up to the end of the 19th century, it was synonymous with poetry. For thousands of years all poems were written in closed form. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that poets like Walt Whitman in America and a group of French poets (who came up with the term vers libre – “free verse“) gave up on meter and begin to write poems without any prescribed forms. Indeed the first, easiest test of whether a poem is in open or closed form is simply to know when it was written: before 1850, closed; after 1850—better check and see.

While the categories below might seem to indicate that the distinction between open and closed form is always clear, it really isn’t. Poems exist on a continuum between fixed/closed and free verse, and even the most formal applications of closed form poetry will often diverge from the “rules” of the form in some way (and when a good poet does that, they do it for a specific reason). Also keep in mind that fixed forms tend to start as individual poems—nonce forms—whose forms other poets find so intriguing that they wish to repeat them. Hence there are innumerable other forms, many more obscure than these presented here. And new forms can always be created while old forms fall into disuse until some clever, historically minded poet recovers them. At the same time poets travel the world, or read the world’s books, in order to find and adapt various forms, the best example of which is perhaps the use of Japanese Haiku in English, a surprisingly successful transformation given how unlike the two languages are in even their basic understanding of the boundaries of a word.

Closed Form Poetry

What is called closed form poetry is an organization of language that adds more than common rigidity to language and then tries to create the maximum possible freedom—or openness—within that space. Closed form is an obstacle course for the poet to run language through as gracefully as possible. Watching language run gracefully through these often formidable obstacles is one of the greatest pleasures of reading poetry.

While there is more than one way for a poem to be considered closed, the vast majority of poems are called “closed” because of their steady beat (meter). Closed form poems also often rhyme, and when they rhyme they do so in consistent and sometimes complex patterns. They also often repeat the same stanza structure. But, in some cases, it is the meter not the rhyme or the stanza that defines the type.

Although meter has been the most prominent element in closed form poetry since the middle ages, there are other things besides meter that determine whether or not a poem is in closed form. But let’s be clear: if a poem is written in meter, it’s closed. As for rhyme, while most poems that rhyme are closed and most open form poems do not rhyme, rhyme alone is not a good indication of whether a poem is in open or closed form. Why? Open form poems sometimes use rhyme (in a limited way), but more importantly many closed form poems do not rhyme.

The pleasure of all fixed form poetry is partly mathematical. This is never truer than in the sonnet. In the Renaissance one expression for writing poetry was “doing numbers.” If you said, “it is written in numbers,” you meant, “it is a poem.” And just rattling off numbers could tell the listener what type of poem it was. The form of a sonnet is mathematically rigid in respect to meter and stanza. The trick is to find freedom and flexibility within this rigidity. The pleasure of a sonnet is the pleasure of maximum freedom within maximum restraint: emotion tied to math. Units of meaning—usually the grammatical sentences—coincide rigidly with the stanza in the earlier sonnets, how the lines tend to stop sharply, and how these aspects of the sonnet loosen up as the centuries pass.

So what besides meter can close a poem?

Alliteration can. Old English poetry (like Beowulf) was written in something called “alliterative verse.” Alliterative poetry is closed by the number of repeated sounds in the line. The line of an alliterative poem has, usually, three instances of the same sound (note the “f” sounds this line: “The folk-kings’ former fame we have heard of”). Alliterative verse does not necessarily count stresses or syllables, only alliterative sounds.

Accent Count Sometime Old English alliterative verse does count accents. When it does, or when any verse does, we call that “accentual verse.” In this type, you can have as many unstressed syllables as you want, but the accented syllables remain constant or follow a pattern.

Syllable count Syllabic verse (such as haiku) counts only syllables. It is not written in meter or rhyme. In fact any poem that maintains the same number of syllables in each line or in corresponding lines in each stanza is closed by syllable count alone.

Accentual-syllabic As you may have guessed from the name, if you count both the syllables and the accents, you have accentual-syllabic verse. The sonnet is an accentual-syllabic form. But so is most English-language poetry.

Pre-established form. Named forms, such as villanelle and sestina, are determined by word or line pattern. Villanelles rhyme, but they don’t have to be in meter. Sestinas don’t rhyme and are rarely in meter.

If none of these criteria apply (meter, alliteration, syllable count or form name), then you can be pretty sure your poem is in open form/free verse.

Varieties of Closed/”Fixed” Forms

The poetic forms included here are by no means representative of all the forms that exist; these are just some of the more common ones you’re likely to come across.

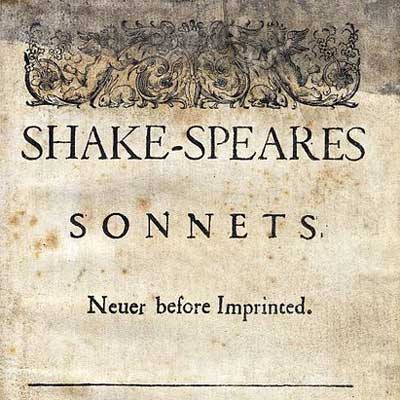

The Sonnet

Credit for the invention of the form is given to the Italian poet Giacomo de Lentino in the 14th century. It is not, however, Lentino but Francesco Petrarca, known as Petrarch, who is most closely associated with the early form of the sonnet. Petrarch established the themes and dominated the practice of the Italian sonnet. Although it’s very likely the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer encountered the form in the late 1300s, it took approximately 200 years for the sonnet form to make its way from Italy to England. In the mid-1500s Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (usually referred to simply as “Surrey”) and Thomas Campion translated Petrarch into English for the first time. Surrey is credited with creating the now Standard English form of the sonnet, although that form is more closely associated with William Shakespeare, who perfected it.

General Form

Typically, a sonnet is a poem consisting of fourteen lines of iambic pentameter. Not much more can be said by way of set-in-stone definition. In fact, even these absolutes of the sonnet have been challenged. Shakespeare wrote one 15-line sonnet. Others have written 16-line poems they have called sonnets. Some, like Philip Sidney, have written iambic hexameter or other lines in what otherwise are called and seem to be sonnets.

In addition to usually being comprised of fourteen lines of iambic pentameter, sonnets generally have a volta, or “turn,” as well. The volta is where, logically, the sonnet switches direction (as sonnets tend to do). The poet will seem to be saying one thing and then suddenly start saying another.

The volta may bring about the answer, at or near the end of a sonnet, to the question being asked up to that point. Or it may occur where a false claim is replaced by a true claim, as in Michael Drayton’s Sonnet 61 in which he tells us in the first part of the poem, “I’m so glad we broke up,” and in the second, “But can we get back together.”

The most common subject of the sonnet is love, particularly in the Italian/Petrarchan form. The story of love most commonly told is the story of unrequited love from the perspective of a man. In this story, the man falls hopelessly in love with a woman who is his moral and social superior. A sonnet is not defined primarily by its subject matter, however. In fact, a sonnet can be about anything at all. The word refers only to the form: the line, the stanza and the rhyme scheme.

Petrarchan (Italian) Sonnet

The following sonnet was written in the sixteenth century by Sir Thomas Wyatt and is one of the earliest sonnets in English. We’ve updated the spellings and changed a few words to make it easier to understand, emphasized the meter of the first line in bold, noted the rhyme scheme, and added a space at a natural breaking point:

Who so wish to hunt, I know where is an hind a

But as for me, alas, I may no more; b

Although the poem seems to be about a man who is hunting a deer, this scene is in fact a metaphor for a man who is trying to seduce a woman who will have no part of him. We should note that the poem, as presented, does not necessarily reveal this to be so.

To see this it helps to know a little about the author and the circumstances in which the poem was written. The “deer” in the poem is probably Anne Boleyn, then the lover of Henry VIII. The “Caesar” in the poem is therefore Henry VIII, who would have had Sir Thomas Wyatt, the author, killed for seducing Anne. It’s a pretty tricky situation. Wyatt obviously could not write about it directly. (He was, in fact, eventually hanged for treason—but not for this). In this early English sonnet, Wyatt has translated an Italian sonnet and applied it to his own situation.

Metric Line: You may notice the extra accented syllable on the first word of the first line. This is a normal kind of variation that a poet employs to keep the reader’s interest or to surprise the reader. It’s one of the ways the poet opens the closed form. Still, the poem is overwhelmingly written, as virtually all sonnets are, in iambic pentameter.

The Rhyme Scheme: abbaabba cddcee. This is one of two most common options for the Italian sonnet. The other has the same first eight lines (the octave) but cdedce for the next six (or sestet). Other variations for the sestet also exist.

The Stanza: Whichever rhyme scheme is chosen, the Italian sonnet breaks into two stanzas as noted above (although the natural division is not usually noted with a space): an eight-line octave and a six-line sestet.

This is the primary difference between the Italian and English forms of the sonnet. The volta generally appears at the point where the octave divides from the sestet. You will notice here that lines one and nine begin with the same word, as though the poet is starting over. The octave of a Petrarchan sonnet will likely present a problem, and the sestet will provide the solution or resolution to that problem.

Shakespearean (English) Sonnet

English, unlike Italian, is a rhyme-poor language. It’s a struggle for an English poet to find enough “a’s” and “b’s” for a sonnet. The most common sonnet form in English is therefore not the Petrarchan but the English or Shakespearean, which allows for a greater number of rhyming words.

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) followed it in all his sonnets—which are the most famous in English. It’s also called the Elizabethan sonnet. Being a sonnet, it has fourteen lines of rhymed iambic pentameter. But the form is different, and it’s less likely to be about the unrequited love of a man for a woman. Here’s an example.

Sonnet 73

So that the meaning doesn’t interfere with the understanding of the form, here’s a paraphrase:

When you look at me you could think about the very end of autumn, when maybe a few last yellow leaves or maybe none at all hang on the boughs of the trees that are shaken by the cold wind.

Or when you look at me you think of the end of the day, after the sunset fades in the west, just before night comes to seal up life in a death-like sleep.

Or when you look at me you see an almost burnt up fire, a fire that has consumed its fuel, and the very substance that nourished it, the way that people consume themselves by burning up their youth.

You see these things when you look at me, and they make your love for me stronger, because you know I will not be around much longer.

Here’s the poem again:

We haven’t scanned the line. But if you do, you will see the regular iambic pentameter throughout. You will notice that the rhyme scheme and stanza form differ from the Petrarchan. Here we have three quatrains and a couplet. And the rhyme scheme is abab cdcd efef gg. These things do not change in a Shakespearean sonnet.

We also notice that the volta comes after line twelve. The first three stanzas elaborate the same idea, which the couplet resolves. Not all Shakespearean sonnets follow this pattern. The stanza forms and rhyme scheme do not change, but the volta can still come after line eight. You have to look for it.

Spenserian Sonnet

While the Petrarchan and Shakespearean forms are the most common in English, there are others. The Spenserian sonnet, named for the chief practitioner, Edmund Spencer, is a variation on the Shakespearean form.

Like the Shakespearean it is written in three quatrains and a couplet. But, unlike the Shakespearean, the quatrains are tied together by the rhyme. Here is an example (from Spenser’s series of Sonnets called Amoretti). If you read through this sonnet for a little while, you will be able to understand the meaning. But all that matters for the moment is that you take in the form:

Sonnet 29

See how the stubborne damzell doth deprave a

my simple meaning with disdaynfull scorne: b

and by the bay which I unto her gave, a

accoumpts my selfe her captive quite forlorne. b

The bay (quoth she) is of the victours borne, b

yielded them by the vanquisht as theyr meeds, c

and they therewith doe poetes heads adorne, b

to sing the glory of their famous deedes c

But sith she will the conquest challenge needs c

let her accept me as her faithfull thrall, d

that her great triumph which my skill exceeds, c

I may in trump of fame blaze over all. d

Then would I decke her head with glorious bayes, e

and fill the world with her victorious prayse. e

We’ve added spaces to make the stanzas clearer. You’ll notice that the end rhyme of the last line of each quatrain is repeated in the first line of the next quatrain, making the division into quatrains suspect. The repeated lines give the poem a couplet every time the stanza changes, and carrying one of the rhymes from stanza to stanza weaves the sounds tightly. However the sense or meaning may change from stanza to stanza, the sounds bind them to each other. A good sonneteer would use this form to play the logic of the form against the logic of the words.

Terza Rima

Terza rima is a special kind of tercet that was used by the Italian poet, Dante in his famous Divine Comedy. It has also been used now and then to great effect in the sonnet.

Terza Rima stanza sequence is similar to the sequence used in the Spenserian sonnet, but one line shorter: a terza rima sequence runs aba bcb cdc, etc.

Percy Bysshe Shelley and Robert Frost have done a particularly good job in this form. Here’s an example, the first of five sonnet stanzas in Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”. In this case the spaces between the stanzas are Shelley’s.

You’ll notice that this sonnet also ends with a couplet.

Nonce Sonnet

There exist other named forms of the sonnet. But they are too rare to mention here.

At the same time, there are many sonnets for which the form is generated once and not repeated. These are called nonce sonnets. They’re still written in fourteen lines of iambic pentameter, but the rhyme scheme and stanza form vary from any established sonnet pattern. The unrivaled greatest of these—and of perhaps all sonnets—is, in our opinion, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” When you read this sonnet, note the rhyme scheme, the internal surprising rhyme, and the complex form accompanying the complex ironies of the content.

“Ozymandias”

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desart. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

[1819]

“Ozymandias” read by Breaking Bad‘s Bryan Cranston:

Ode

The ode comes in a number of flavors—Pindaric, Horatian, English, Irregular. We’re not going to cover them individually. Some are very strict in form, some very loose.

Its origins are in the Latin poetry of the Roman Empire, and there its form is very strict. Some English poets imitated Latin form. But most practitioners of the Ode in English have taken only some of the particulars of the Ancient ode to heart as they reproduce the form. The ode is a longer poem, serious or meditative in nature, commonly about events of a public nature, written in formal language and usually having a strict stanzaic structure.

It’s hard to come up with a better definition than that because the actual poems that call themselves odes vary a lot. Pope’s “Ode on Solitude” is a short poem—unusual for an ode—while Keats’ “great odes” are about very private matters. In fact, from the late 18th century on, odes commemorating public events rarely survive the event of their publication. The odes we read today do not seem so public. Let’s look briefly at two odes, one with a regular stanza, the other irregular.

Regular odes, such as those of Keats, are often composed in very elaborate stanzas. Students often find these difficult to read because of the form and because of the elaborate language.

Here’s the first stanza of “Ode to a Nightingale.” It’s intimidating even to look at:

This is exactly the kind of thing that makes students say they hate poetry. It can make you feel stupid. That’s a false impression however. You can scan the poem and note the rhyme scheme if you like. We’re going to be concerned with the language—which is the most significant feature that separates the ode from other forms.

What should you notice about it? You may or may not have found the Shakespearean sonnet difficult. If you did, it was not because the language was difficult; it was because the language is old. If you’d lived in 1595, you would not have had trouble reading Shakespeare. By contrast, Keats’ ode has always been difficult. It uses words that were unusual or specialized even in its own day. It also has the most formal syntax possible, and allusions only educated people could get. (Did the average coal miner of the early 19th century know of the river “Lethe,” the classical river of forgetfulness through which the dead soul passed in order to forget its early life as it crossed into the underworld? It was one of five rivers in Hades.)

Here’s a paraphrase: Listening to you, little nightingale, makes my heart ache and I feel a drowsy numbness pain my senses as though I’d drunk the deadly poison Hemlock or as though I’d drunk some other dulling drug to the bottom of the glass. If I’d listened to your song one more minute, I think I would have sunk down into the river of forgetfulness. It’s not because I envy your happy life that I feel this way; it’s because you are too happy in your happiness. It’s because you—light-winged spirit of the trees—sing your strong, beautiful song about summer (in a musical place full of green trees and lots of shadows) so easily, so naturally. [Whereas I, the poor human poet, have to work so damn hard to make my poems—and I don’t end up with anything so beautiful as your song.]

The meaning isn’t hard. Only the language.

As far as the stanza goes I want you to notice that although it is as formal as a sonnet, the stanza was freely chosen. If Keats had written the ode in some other stanza, it would still be an ode. The length of the stanza and of the poem is up to the poet as well. He’s not restricted to a certain number of lines.

Beyond the structure (it needs to have some structure), and the language (formal) and the subject matter (serious), any restrictions the poet puts on him or herself are freely chosen.

The irregular ode is even more free. Here’s a sample stanza from “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” by William Wordsworth:

You’ll notice that words like “celestial” (heavenly) and “yore” are very formal. The tone of the poem is serious, but the line length varies quite a lot—more even than it seems to from looking at it. The long lines are not all the same length nor are the short lines. (If you scan this yourself you will see this. The rhyme scheme is also unpredictable.)

Both the sonnet and the ode are formal poems, but for the most part the ode is a more open form in English than the sonnet. The poet is freer to choose the length and the stanza and the rhyme scheme. (But the poet may have less room for choice in the subject matter or tone.)

Ballad

The ballad gets us back to the very roots of poetry. One of the oldest reasons that poems have rhyme and meter is that these elements made the poems easier to memorize. We have kept rhyme and meter so long because they are pleasurable in themselves. But preliterate people used them also for their mnemonic value. The ballad is among the oldest forms in English verse. Not only can it be easily remembered, it can easily be set to music and sung. Virtually all ballads have in common the stanzaic form (but not every poem using this form is a ballad). The ballad stanza or ballad quatrain is a four-line stanza that rhymes abcb (or sometimes abab). It consists of either four lines in iambic tetrameter, or alternating iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. The first is called “eights and eights” because there are eight syllables in each line. The second option is called “eights and sixes.”

Eights and eights:

O, she is young and she is fair

With evil eye that longs to roam.

But she is mine, and so beware

If e’er into her eye you come.

Eights and sixes:

When as King Henry rulde this land,

The second of that name,

Besides the queene, he dearly lovde

A faire and comely dame.

Early folk ballads were meant to be sung in the evening or on holidays to entertain weary hardworking people. They differ from literary ballads in that they have no individual author. They came into being before copyright, and, having no owners, and being easily remembered, were told and retold, written and rewritten over and over. Just about the only language today that circulates like a ballad did in the fourteenth century is a joke. People improved ballads in retelling or just replaced forgotten stanzas with their own. Once they were finally written (and many of course were never written down and have been lost) they very likely were written down in several versions.

Aside from their stanza form (they can be any length of course) the one thing they have in common with literary ballads is that they tell a story. Usually it’s a sad story, often a sad love story. Ballads also often have refrains: repeated lines or stanzas.

An example of a literary ballad is Keats’ “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.” This ballad can properly exist in only one form—Keats’ final version. Although its story is quasi-medieval (it seems to tell the kind of story an ancient folk ballad would have told), it’s much more regular in its meter than the folk ballad is. It seems to have been written (as it was) by a self-conscious poet who was very carefully composing a poem, not by a wandering minstrel who is trading entertaining stories for bread. He will not be able to compensate for the imperfections in his meter with his voice.

Elegy

As with so many words in the study of poetry, this one has a complex history and may designate different things at different times. An elegy is a mournful, melancholy or plaintive poem, especially a lament for the dead or a funeral song. The term “elegy,” which originally denoted a type of poetic meter (elegiac meter), commonly describes a poem of mourning. An elegy may also reflect something that seems to the author to be strange or mysterious. The elegy, as a reflection on a death, on a sorrow more generally, or on something mysterious, may be classified as a form of lyric poetry.

Dramatic Monologue

If epic provides the best example of narrative poetry, dramatic monologue provides at least the most identifiable example of dramatic poetry. Narrative poetry tells a story; dramatic poetry presents a situation. This type of poem was particularly popular in the 19th century, and the master practitioner is Robert Browning. Browning will allow an imaginary character to speak. And as there was no narrator to help orient the reader into the action, and there is never more than a single speaker whose words are available to us, the reader is compelled to reconstruct what is going on in the scene through the words of this single speaker. Complicating the situation still further is the fact that the tone of the speech is often at odds with the subject. The readers’ reaction is first stalled and then intensified by, for example, a murderer explaining in such a matter-of-fact way how and why he has killed his beloved. The dramatic monologue is often described as a speech from an unwritten play.

Villanelle

Like so many French forms, the villanelle is complex and difficult to write. Unlike the dramatic monologue, it is defined by form rather than content. In this it resembles the sonnet. It is a great form for showing off. It consists of 19 lines:

- five tercets that rhyme aba, and

- an ending quatrain that rhymes abaa

The real distinctive feature of the form, however, is the repetition of the first and third lines of the first stanza in specific places throughout the poem. The first line of the first stanza will be repeated as the last line of the second and fourth stanzas and the third line of the final stanza. The last line of the first stanza will recur as the last line of the third, fifth and final stanzas. In the best examples of the type, the meaning of the lines varies slightly with every iteration though the words do not change at all.

Probably the most famous poem of this form is Dylan Thomas’s “Do not go gentle into that good night”:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Sestina

Yet more complex is the sestina. Like the villanelle, the sestina has no set line length. In fact in the shortest possible version of the form, Lloyd Shwartz has published a sestina containing only six different words, one word per line. Most sestinas are much longer. What matters here is not meter or rhyme but the word that ends each line. The form consists of

- six six-line stanzas and

- one three-line final stanza (called an envoy).

The last word of each of the six lines of the first stanza must be repeated as the last word of each of the six lines of every other stanza before the envoy, in the following invariable order:

1-2-3-4-5-6 (in stanza one)

6-1-5-2-4-3 (in stanza two),

3-6-4-1-2-5 (in stanza three),

5-3-2-6-1-4 (in stanza four),

4-5-1-3-6-2 (in stanza five), and

2-4-6-5-3-1 (in stanza six).

5-3-2 (in the envoy)

You will notice that numbers are used to designate these words rather than letters; this is because there is no requirement that the words rhyme, and overwhelmingly they do not. In addition to the ending words, the envoy incorporates the other three words in the middle of each line in the order 1-4-6. Here is an example by Sakadichi Hartmann (1867-1944):

“Sweet Are The Dreams on The Breeze-Blown Strand”

When autumn cloudlets fleck the sky

Straying southward like birds o’er the sea,

When the flickering sunlight on the dunes

Is pale, as seagrasses kissed by the spray,

Seagrasses that knew the summer of yesterday–

Sweet are the dreams on the breeze-blown strand!

Sweet are the dreams on the breeze-blown strand!

When cloud skiffs skim athwart the sky

And like a phantom of yesterday

The light house shimmers out to sea

Pale as the sand and the sea-worn spray

And the straggling sunlight on the dunes.

Like straggling sunlight on the dunes,

Like opal surges that wash the strand

With briny fragrance, adoom with the spray,

Like wander-birds that career the sky

To flowerlit isles of some Southern sea-

Such are the dreams of yesterday!

Alas, our dreams of yesterday,

Frail as the fragrance of the dunes,

Vain as dark jewels of the sea

Cast up on some glimmering strand,

They vanish like cloud sails on the sky,

Pale as seagrasses frowsed by the spray.

Pale as seagrasses kissed by the spray,

Is all this life of yesterday,

All our longings for clear blue skies

For the low cool plash on autumn dunes,

All our musings on tide-left strands

While birds wing southward o’er the sea.

Like birds winging southward o’er the sea

Scattered in air-like wasteful spray,

Sea-fancies fading on lonesome strands

Weary of storm drifts of yesterday,

Thus our thoughts on the sea-scooped dunes

When autumn cloudlets fleck the sky.

Oh, autumn-sea under a cloud-flecked sky

As caressed are thy dunes with opal spray

So shimmer in dreams on the breeze-blown strand

Sweet long-lost summers of yesterday.

Haiku

Haiku is a popular form of unrhymed Japanese poetry. In Japanese, it is generally written in a single vertical line containing three sections, totaling 17 syllables* structured in a 5–7–5 pattern. In English haiku, the 5-7-5 structure is separated into lines. Traditionally, haiku contain a kireji, or cutting word, usually placed at the end of one of the poem’s three sections, and a kigo, or season-word. The most famous exponent of the haiku was Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694). An example of his writing:

- 富士の風や扇にのせて江戸土産

- (fuji no kaze ya oogi ni nosete Edo miyage)

English translation:

- the wind of Mt. Fuji

- I’ve brought on my fan!

- a gift from Edo

Limerick

A limerick is a poem that consists of five lines and is often humorous (if not bawdy). Rhythm is very important in limericks for the first, second and fifth lines must have seven to ten syllables. However, the third and fourth lines only need five to seven. Lines 1, 2 and 5 rhyme with each other, and lines 3 and 4 rhyme with each other. Here is an example of unknown origin:

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.

Ghazal

The ghazal (also ghazel, gazel, gazal, or gozol) is a form of poetry common in Arabic, Bengali, Persian, and Urdu. In classic form, the ghazal has from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share a refrain at the end of the second line. This refrain may be of one or several syllables and is preceded by a rhyme. Each line has an identical meter and is of the same length. The ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity. Here is an example by Agha Shahid Ali (1949-2001):

Where are you now? Who lies beneath your spell tonight?

Whom else from rapture’s road will you expel tonight?

Those “Fabrics of Cashmere—” “to make Me beautiful—”

“Trinket”— to gem– “Me to adorn– How– tell”— tonight?

I beg for haven: Prisons, let open your gates–

A refugee from Belief seeks a cell tonight.

God’s vintage loneliness has turned to vinegar–

All the archangels– their wings frozen– fell tonight.

Lord, cried out the idols, Don’t let us be broken

Only we can convert the infidel tonight.

Mughal ceilings, let your mirrored convexities

multiply me at once under your spell tonight.

He’s freed some fire from ice in pity for Heaven.

He’s left open– for God– the doors of Hell tonight.

In the heart’s veined temple, all statues have been smashed

No priest in saffron’s left to toll its knell tonight.

God, limit these punishments, there’s still Judgment Day–

I’m a mere sinner, I’m no infidel tonight.

Executioners near the woman at the window.

Damn you, Elijah, I’ll bless Jezebel tonight.

The hunt is over, and I hear the Call to Prayer

fade into that of the wounded gazelle tonight.

My rivals for your love– you’ve invited them all?

This is mere insult, this is no farewell tonight.

And I, Shahid, only am escaped to tell thee–

God sobs in my arms. Call me Ishmael tonight.

Cinquain

Cinquain (/ˈsɪŋkeɪn/ SING-kayn) is a class of poetic forms that employ a 5-line pattern. Earlier used to describe any five-line form, it now refers to one of several forms that are defined by specific rules and guidelines. The modern form, known as American cinquain is inspired by Japanese haiku and tanka and is akin in spirit to that of the Imagists.

In her 1915 collection titled Verse, published a year after her death, Adelaide Crapsey included 28 cinquains. Crapsey’s American Cinquain form developed in two stages. The first, fundamental form is a stanza of five lines of accentual verse, in which the lines comprise, in order, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 1 stresses. Then Crapsey decided to make the criterion a stanza of five lines of accentual-syllabic verse, in which the lines comprise, in order, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 1 stresses and 2, 4, 6, 8, and 2 syllables. Iambic feet were meant to be the standard for the cinquain, which made the dual criteria match perfectly. Some resource materials define classic cinquains as solely iambic, but that is not necessarily so. In contrast to the Eastern forms upon which she based them, Crapsey always titled her cinquains, effectively utilizing the title as a sixth line. Crapsey’s cinquain depends on strict structure and intense physical imagery to communicate a mood or feeling.

The form is illustrated by Crapsey’s “November Night”:

Listen…

With faint dry sound,

Like steps of passing ghosts,

The leaves, frost-crisp’d, break from the trees

And fall.

Numerous variations on this form have also popped up over the years.

Free Verse (Open Form Poetry)

Open form poetry is significantly less rigid than closed form, and it is only by contrast with closed form that it can be called open. It is usually less rigid in regard to line, stanza, meter, and subject matter—in short everything formal that has traditionally made a poem a poem. It seems to be in some ways closer to prose than to closed form poetry but, at the same time, it is still not so “open” as prose generally is.

The pleasure we get from closed form is to see how the language can play—can create room—within rigid form. That’s why knowing the forms helps us appreciate and enjoy that poetry more. To say it another way, we look for what freedom the language can attain within the artificial restraint of form.

That advantage is lost in degree as the form becomes less restricted. If other pleasures do not compensate, the movement from closed form to open is wasted. The pleasure offered by open form poems certainly runs the risk of not being the pleasure of poetry.

Before talking more about this sort of poem—which became so dominant in the twentieth century that for many years other forms of poetry were rarely published—let’s look at a few examples.

Here’s a particularly notorious example by William Carlos Williams (you certainly can’t say it’s hard to read):

“The Red Wheelbarrow”

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

We could talk about the meaning of this poem in detail. But for now, I want to ask the question: in what sense is this verse free? Well, it doesn’t rhyme. It does not have a consistent meter. But it does have a consistent line and stanza: each stanza consists of one three-word line followed by one one-word line. Williams has even broken up the single word “wheelbarrow” into two words to fit his form. It is as rigorous as a haiku in its way. It just doesn’t follow rules previously put down by a poetic tradition. Because the history of poetry does not consider word count (as distinct from syllable count) an element of closed form, the poem is considered to be open form. It would show up near the middle of our continuum circle.

Here’s another, by H. D. (Hilda Doolittle, 1886-1961)

“Sea Rose”

Rose, harsh rose,

marred and with stint of petals,

meager flower, thin,

sparse of leaf

more precious

than a wet rose

single on a stem—

you are caught in the drift

Stunted, with small leaf

you are slung on the sand

you are lifted

in the crisp sand

that drives in the wind.

Can the spice-rose

Drip such acrid fragrance

Hardened in a leaf?

Again, in what way is this poem free? Well, in addition to the ways that Williams’ poem is free, this one lacks a consistent meter, line and stanza. It seems to have a consistent four-line stanza through the first two. But then the next one is five lines and the final one three. (Look how easily the poet could have turned these sixteen lines into four-line stanzas if she had wanted to.)

Free verse is generally easy to recognize. What is harder to recognize is the principle of order that free verse poems employ. But there usually is one: it may be the number of words or syllables in a line, it may be the grammatical clause; it may be the principle of the breath (the line pauses when the poet expects the reader to breathe), or it might be that the line seeks the most dramatic moment at which to break. It may be that the first word of the next line changes the meaning of the last word of the previous one, as the word “not” did in the recent language fad when it was stuck at the end of a sentence. For the sake of analysis we want to discover what makes a free verse poem a poem, and not just broken up prose. But if it is a matter of identifying the form of the poem, this is much simpler: anything that’s not closed form, is open.

One of the things you discover in reading open form poems is that each must be taken in itself, with as few preconceptions as possible.

How did poems become open anyway?

Before ending this chapter, it might be useful to pursue, briefly, one other question: How did closed form poetry so suddenly become open form poetry?

That question has been answered in diverse ways, but we will mention only two.

Formally, the problem faced by early twentieth-century – when the popularity of open form began to overtake that of closed form – English language poets felt a sense that the closed forms were used up. It was believed by many that closed form had been exhausted, that nothing new could be done with it, and that nothing new could be said in it. It’s certainly true that there are a limited number of things that can be done in meter, and that after 900 years or so, meter and rhyme were becoming a little old.

Ideologically, the problem was that closed form didn’t seem to fit the times. The way we say things says a lot about how we think. Closed form expresses a more rigid view of the world, one more sympathetic to monarchy than to democracy. (Walt Whitman in the middle of the nineteenth century had already rejected traditional closed form for his democratic poem.) Open form simply fits better with the open twentieth-century view of the difference and the significance of the individual.

Page content is remixed from Introduction to Poetry Copyright © 2019 by Alan Lindsay and Candace Bergstrom licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, and Wikipedia under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 License