4 The Literary Landscape

“Form” and “Genre”

In the study of literature, the terms “form” and “genre” are sometimes used interchangeably, but they can be distinct. According to The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory:

“When we speak of the form of a literary work we refer to its shape and structure and to the manner in which it is made – as opposed to its substance or what it is about. […] A secondary meaning of form is the kind of work – the genre to which it belongs. Thus: sonnet, short story, essay.”

So, one definition of “form” specifically refers to how it’s structured, the nature of the writing’s organization. On the other hand, “form” in the sense of “genre” has to do with the subject of the writing. Either of these terms may be used to categorize literature into the four areas covered below, but keep in mind that “genre” is possibly more helpful if reserved for categorizing works based on what they’re about (e.g. “romance,” “mystery,” etc.). For example, if a poem is about a struggling colony on a moon of Jupiter, then one might argue its form is “poetry” and its genre is “science fiction.”

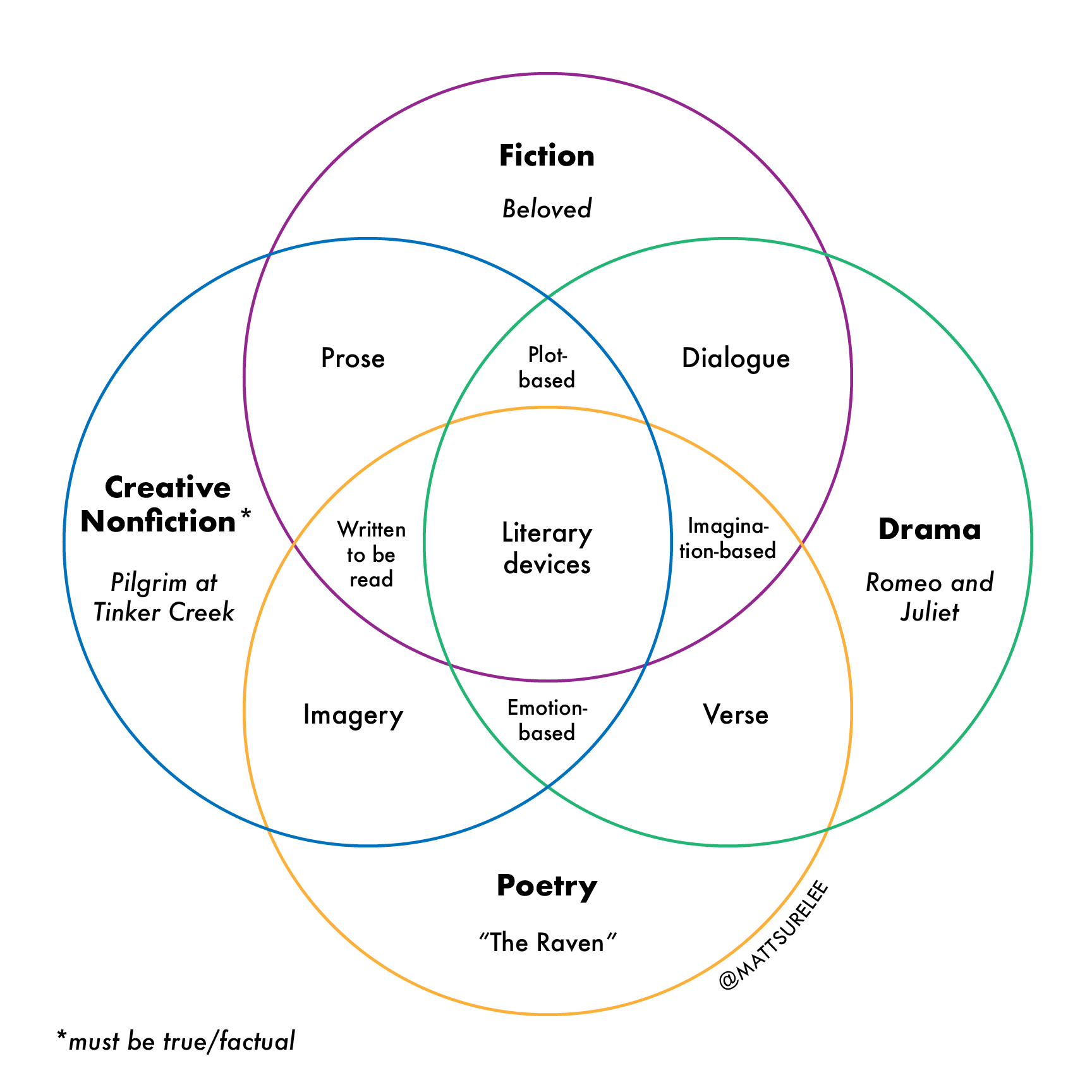

In the landscape of literature, there are four major forms: poetry, drama, fiction, and creative nonfiction. While there are certain key recognizable features of each form, these are not so much rules as they are tools, or conventions, the author uses. If we think of literature as its own world, it may help to think of forms more as regions with open borders, where there are no walls and that authors can freely move through if they desire. But, like any traveler, it helps you understand your place in the world if you know where you are located (or at least the “lay of the land”). It can also be interesting to analyze how certain texts break formal conventions. These major forms are briefly outlined below, and in later sections we will address the characteristics of each form in greater detail.

“Literary Genres Venn Diagram” by Matt Shirley (2021) licensed CC-BY-SA. This image shows some of the differences and overlap between different forms.

Poetry/Verse

Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, prosaic ostensible meaning (ordinary intended meaning). Poetry has traditionally been distinguished from prose by its being set in verse;[4] prose is cast in sentences, poetry in lines; the syntax of prose is dictated by meaning, whereas that of poetry is held across metre or the visual aspects of the poem.[5]

Prior to the nineteenth century, poetry was commonly understood to be something set in metrical lines; accordingly, in 1658 a definition of poetry is “any kind of subject consisting of Rythm or Verses”.[6] Possibly as a result of Aristotle’s influence (his Poetics), “poetry” before the nineteenth century was usually less a technical designation for verse than a normative category of fictive or rhetorical art.[7] As a form it may pre-date literacy, with the earliest works being composed within and sustained by an oral tradition;[8] hence it constitutes the earliest example of literature.

Core attributes of poetry/verse:

- Emphasis on image or feeling

- More emphasis on rhythm and meter than other genres (older drama, like Shakespeare, often uses rhythm and meter)

- Sometimes rhymes, but not always

- Organized through stanzas and lines

- Does not require a plot or characters, although it may include them (such as in narrative poetry). Often focuses on single moment or feeling or image

- Meant to be heard as well as read, so there is an emphasis on sound

Example

“I wandered lonely as a cloud” by William Wordsworth (1807)

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees, 5

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay: 10

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company: 15

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude; 20

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

In-Text Citation: Wordsworth personified the daffodils as “dancing” (6). The 6 corresponds to the line number.

Works Cited Entry: Wordsworth, William. “I wandered lonely as a cloud.” Poems in Two Volumes. London: Longman, 1807.

Drama

Drama is literature intended for performance.[13]

Core attributes of drama:

- Meant to be performed to an audience

- Character List (often); Character names indicate who is speaking (almost always)

- Heavy inclusion of dialogue. Usually not much scene description (compared to other genres)

- Organized by Acts and Scenes (and sometimes Line Numbers)

- May include stage directions, but may not

- Plot based (it tells a story, usually involving a conflict of some kind)

- May be written in verse

- Types: Comedy, Tragedy, History, and Romance, among others

Example

The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde (excerpt)

THE PERSONS IN THE PLAY

John Worthing, J.P.

Algernon Moncrieff

Rev. Canon Chasuble, D.D.

Merriman, Butler

Lane, Manservant

Lady Bracknell

Hon. Gwendolen Fairfax

Cecily Cardew

Miss Prism, Governess

ACT 1 SCENE 1

1 Morning-room in Algernon’s flat in Half-Moon Street. The room is luxuriously and artistically furnished. The sound of a piano is heard in the adjoining room.

2 [Lane is arranging afternoon tea on the table, and after the music has ceased, Algernon enters.]

3 Algernon. Did you hear what I was playing, Lane?

4 Lane. I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir.

5 Algernon. I’m sorry for that, for your sake. I don’t play accurately—any one can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life.

6 Lane. Yes, sir.

7 Algernon. And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

8 Lane. Yes, sir. [Hands them on a salver.]

9 Algernon. [Inspects them, takes two, and sits down on the sofa.] Oh! . . . by the way, Lane, I see from your book that on Thursday night, when Lord 10 Shoreman and Mr. Worthing were dining with me, eight bottles of champagne are entered as having been consumed.

Fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with history, fact, or plausibility. In a traditional narrow sense, “fiction” refers to written narratives in prose.

Prose is a form of language that possesses ordinary syntax and natural speech rather than rhythmic structure; in which regard, along with its measurement in sentences rather than lines, it differs from poetry.[9]

- Novel: a long fictional prose narrative.

- Novella:The novella exists between the novel and short story; the publisher Melville House classifies it as “too short to be a novel, too long to be a short story.”[10]

- Short story: a dilemma in defining the “short story” as a literary form is how to, or whether one should, distinguish it from any short narrative. Apart from its distinct size, various theorists have suggested that the short story has a characteristic subject matter or structure;[11] these discussions often position the form in some relation to the novel.[12]

Core attributes of fiction:

- Prose

- Created from the imagination. May be inspired by real events or people, but not chained by the constraints of reality.

- Plot-based

- Character-based

- Usually includes dialogue and physical descriptions

- Organized through paragraphs and sentences

- Types: Short Story, Novella, Novel

Example

Virginia Woolf, “Kew Gardens” (excerpt)

From the oval-shaped flower-bed there rose perhaps a hundred stalks spreading into heart-shaped or tongue-shaped leaves half way up and unfurling at the tip red or blue or yellow petals marked with spots of colour raised upon the surface; and from the red, blue or yellow gloom of the throat emerged a straight bar, rough with gold dust and slightly clubbed at the end. The petals were voluminous enough to be stirred by the summer breeze, and when they moved, the red, blue and yellow lights passed one over the other, staining an inch of the brown earth beneath with a spot of the most intricate colour. The light fell either upon the smooth, grey back of a pebble, or, the shell of a snail with its brown, circular veins, or falling into a raindrop, it expanded with such intensity of red, blue and yellow the thin walls of water that one expected them to burst and disappear. Instead, the drop was left in a second silver grey once more, and the light now settled upon the flesh of a leaf, revealing the branching thread of fibre beneath the surface, and again it moved on and spread its illumination in the vast green spaces beneath the dome of the heart-shaped and tongue-shaped leaves. Then the breeze stirred rather more briskly overhead and the colour was flashed into the air above, into the eyes of the men and women who walk in Kew Gardens in July.

Creative Nonfiction

While this course doesn’t cover this major literary form, it’s nonetheless helpful to note its characteristics to help you distinguish it from fiction.

- Prose

- True (not fabricated, not from the imagination). This is a *very important* distinction from the other genres.

- Plot-based

- Character-based

- Usually includes dialogue and scene descriptions

- Organized through paragraphs and sentences

- Types: Narrative, Memoir, and Literary Journalism, among others

Example

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (excerpt)

I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Knowledge Check!

Works Cited

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. Boston Anti-Slavery Office, Boston, 1845.

“Form.” Cuddon, J. A., and Rafey Habib. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. Edited by Matthew Birchwood et al., Fifth edition, Penguin Books, 2013.

Wilde, Oscar. The Importance of Being Earnest. London: St. James’ Theatre, 1895.

Woolf, Virginia. “Kew Gardens.” Monday or Tuesday. New York: Harcourt, 1921.

Wordsworth, William. “I wandered lonely as a cloud.” Poems in Two Volumes. London: Longman, 1807.

Footnotes

- Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 28

- Ross, “The Emergence of “Literature”: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century,” 406 & Eagleton, Literary theory: an introduction, 16

- Leitch et al., The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 28

- “poetry, n.”. Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Retrieved 13 February 2014. (subscription required)

- Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 938–9

- “poetry, n.”. Oxford English Dictionary. OUP. Retrieved 13 February 2014. (subscription required)

- Ross, “The Emergence of “Literature”: Making and Reading the English Canon in the Eighteenth Century”, 398

- Finnegan, Ruth H. (1977). Oral poetry: its nature, significance, and social context. Indiana University Press. p. 66. & Magoun, Jr., Francis P. (1953). “Oral-Formulaic Character of Anglo-Saxon Narrative Poetry”. Speculum 28 (3): 446–67. doi:10.2307/2847021

- Preminger, The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 938–9 &Alison Booth; Kelly J. Mays. “Glossary: P”.LitWeb, the Norton Introduction to Literature Studyspace. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- Antrim, Taylor (2010). “In Praise of Short”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- Rohrberger, Mary; Dan E. Burns (1982). “Short Fiction and the Numinous Realm: Another Attempt at Definition”. Modern Fiction Studies. XXVIII (6). & May, Charles (1995). The Short Story. The Reality of Artifice. New York: Twain.

- Marie Louise Pratt (1994). Charles May, ed. The Short Story: The Long and the Short of It. Athens: Ohio UP.

- Elam, Kier (1980). The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. London and New York: Methuen. p. 98.ISBN 0-416-72060-9.

Page content remixes adaptations from “Literature” from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literature#cite_note-44 ) under CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike via Lumen Learning and 1.8: The Literary Landscape- Four Major Genres is shared under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap Links to an external site. (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative ) .

“Fiction” adapted from Wikipedia, under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License 4.0 .