5 Urinary System

Learning Objectives

- Apply the rules of medical language to build, analyze, spell, pronounce, abbreviate, and define terms as they relate to the urinary system

- Identify meanings of key word components of the urinary system

- Use terms related to the urinary system

Urinary System Word Parts

Click on prefixes, combining forms, and suffixes to reveal a list of word parts to memorize for the urinary system. Then use the flashcards below to practice.

Introduction to the Urinary System

The urinary system has roles you may be well aware of. Cleansing the blood and ridding the body of wastes probably come to mind. However, there are additional, equally important functions, played by the system. Take, for example, regulation of pH, a function shared with the lungs and the buffers in the blood. Additionally, the regulation of blood pressure is a role shared with the heart and blood vessels. What about regulating the concentration of solutes in the blood? Did you know that the kidney is important in determining the concentration of red blood cells? Eighty-five percent of the erythropoietin (EPO) produced to stimulate red blood cell production is produced in the kidneys. The kidneys also help control blood pressure by producing the enzyme renin . Additionally, the kidneys perform the final synthesis step of vitamin D production, converting calcidiol to calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D. If the kidneys fail, these functions are compromised or lost altogether, with devastating effects on homeostasis.

Urinary System Medical Terms

Anatomy (Structures) of the Urinary System

Kidney(s)

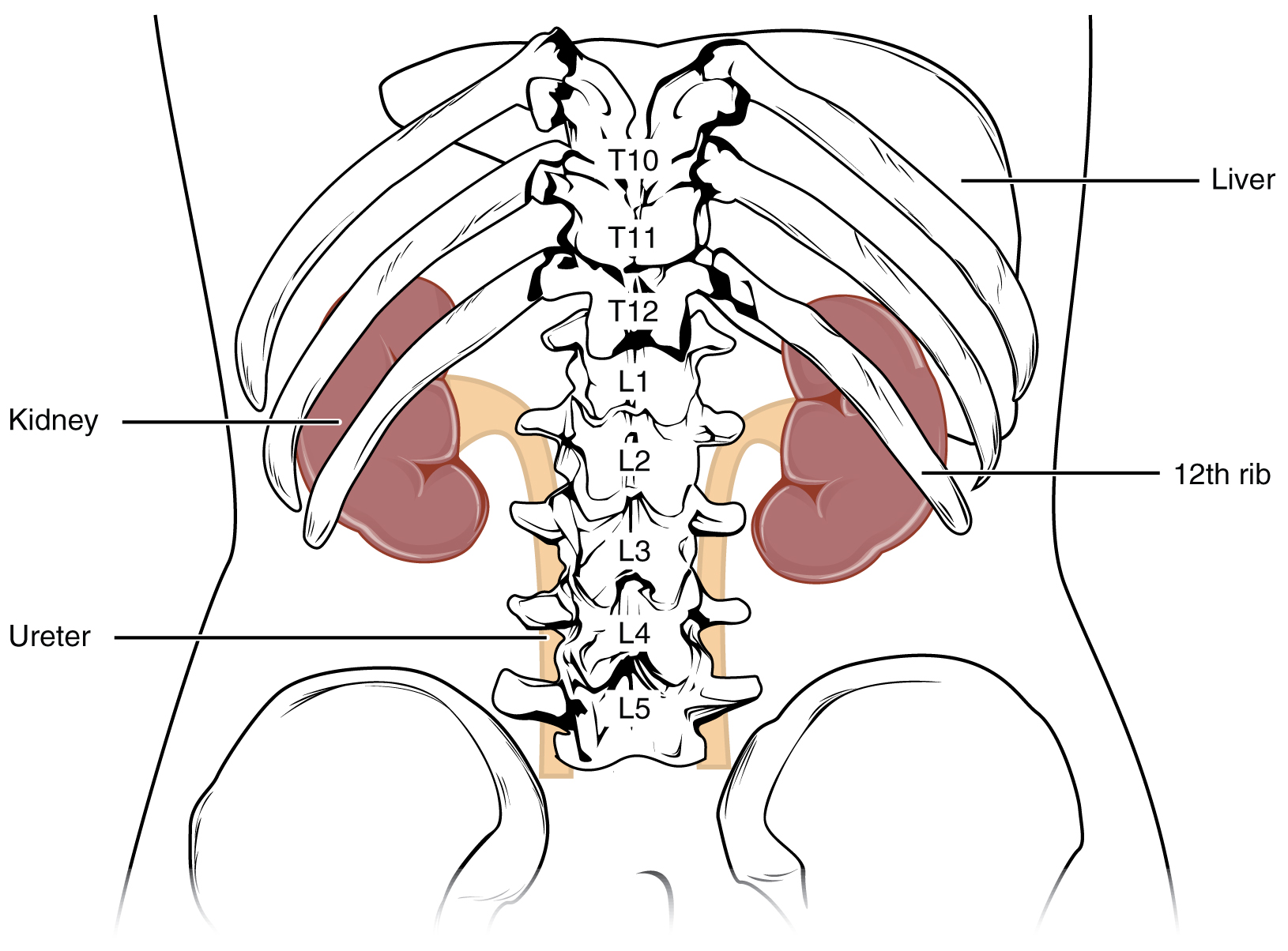

The kidneys lie on either side of the spine in the retroperitoneal space between the parietal peritoneum and the posterior abdominal wall, well protected by muscle, fat, and ribs. They are roughly the size of your fist. The male kidney is typically a bit larger than the female kidney. The kidneys are well vascularized, receiving about twenty-five percent of the cardiac output at rest. Figure 5.1 displays the location of the kidneys.

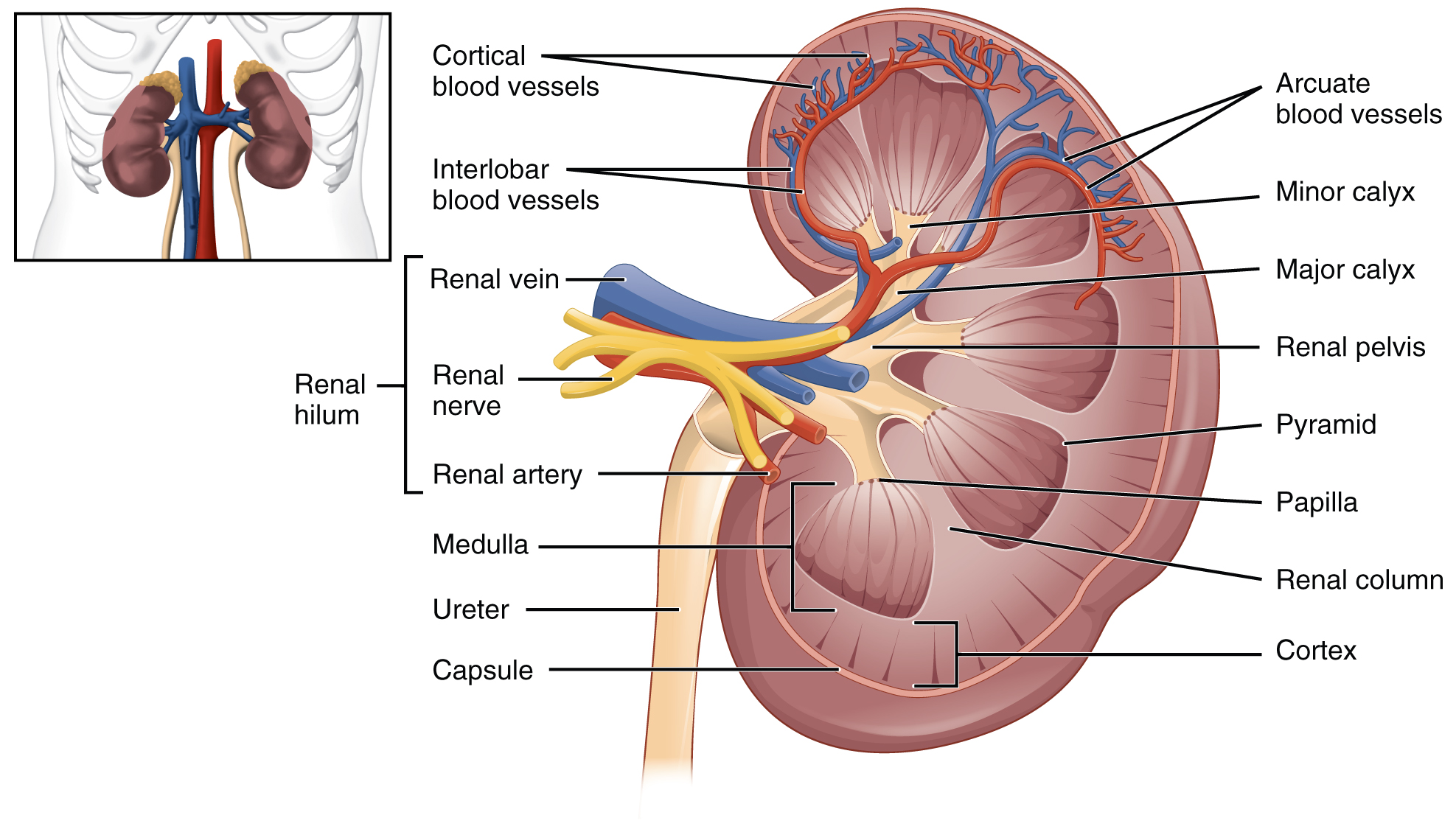

Kidneys’ Internal Structure

A frontal section through the kidney reveals an outer region called the renal cortex and an inner region called the medulla (see Figure 5.2). The renal columns are connective tissue extensions that radiate downward from the cortex through the medulla to separate the most characteristic features of the medulla, the renal pyramids and renal papillae. The papillae are bundles of collecting ducts that transport urine made by nephrons to the calyces of the kidney for excretion. The renal columns also serve to divide the kidney into 6–8 lobes and provide a supportive framework for vessels that enter and exit the cortex. The pyramids and renal columns taken together constitute the kidney lobes.

Renal Hilum

The renal hilum is the entry and exit site for structures servicing the kidneys: vessels, nerves, lymphatics, and ureters. The medial-facing hila are tucked into the sweeping convex outline of the cortex. Emerging from the hilum is the renal pelvis, which is formed from the major and minor calyxes in the kidney. The smooth muscle in the renal pelvis funnels urine via peristalsis into the ureter. The renal arteries form directly from the descending aorta, whereas the renal veins return cleansed blood directly to the inferior vena cava. The artery, vein, and renal pelvis are arranged in an anterior-to-posterior order.

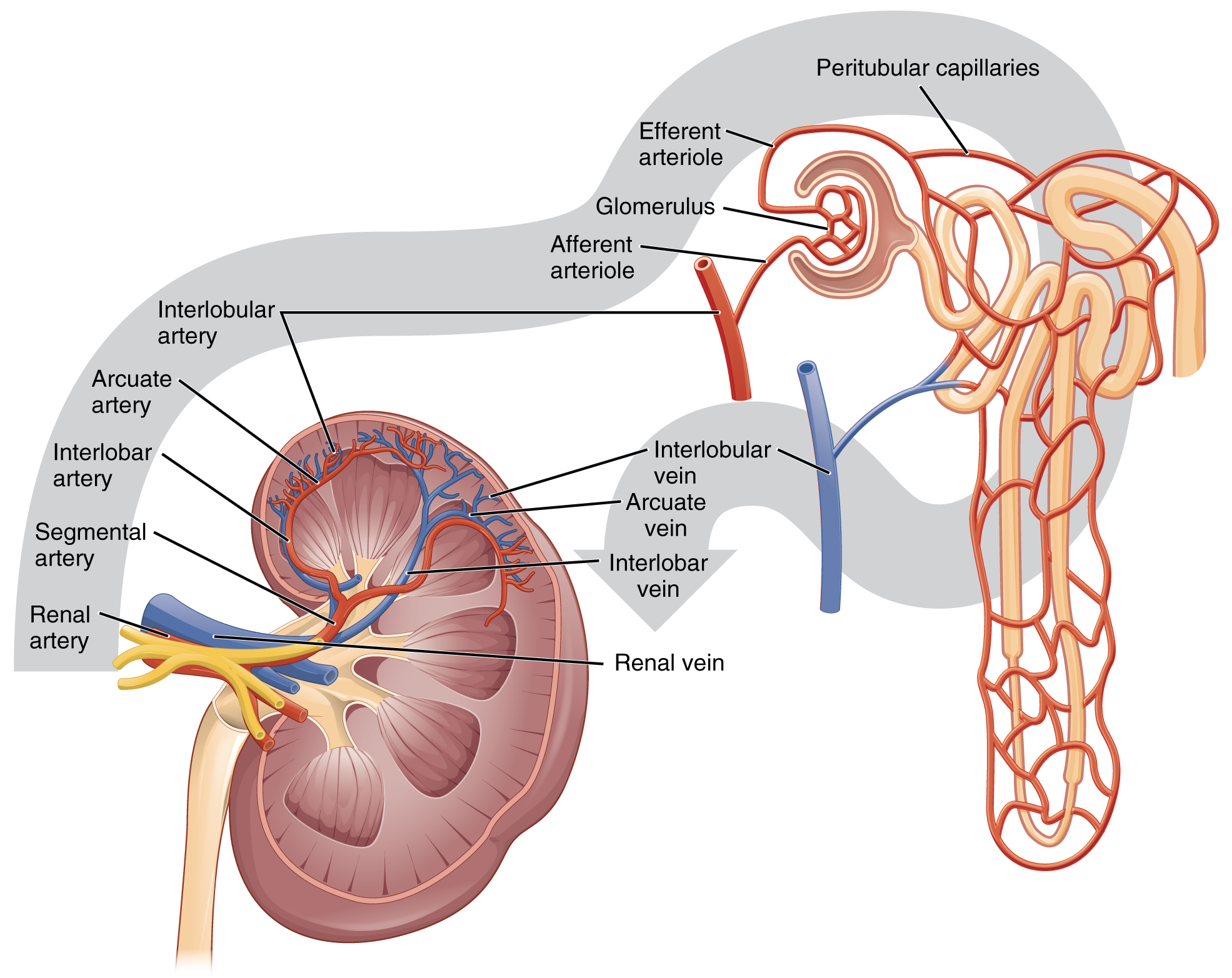

Nephrons and Vessels

The renal artery first divides into segmental arteries, followed by further branching to form interlobar arteries that pass through the renal columns to reach the cortex (see Figure 5.3). The interlobar arteries, in turn, branch into arcuate arteries, cortical radiate arteries, and then into afferent arterioles. The afferent arterioles service about 1.3 million nephrons in each kidney.

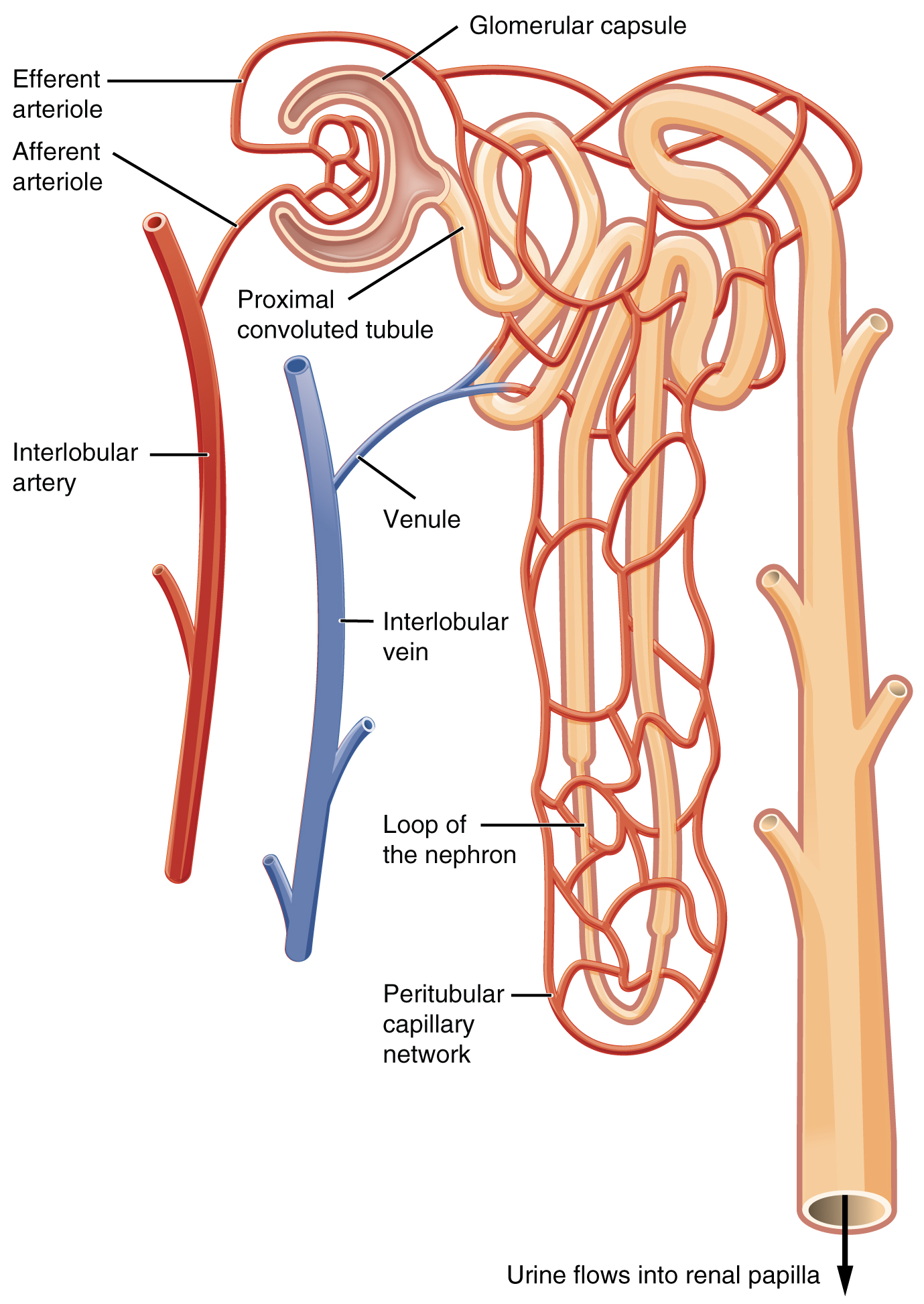

Nephrons are the “functional units” of the kidney; they cleanse the blood and balance the constituents of the circulation. The afferent arterioles form a tuft of high-pressure capillaries about 200 µm in diameter, the glomerulus. The rest of the nephron consists of a continuous sophisticated tubule whose proximal end surrounds the glomerulus in an intimate embrace—this is Bowman’s capsule. The glomerulus and Bowman’s capsule together form the renal corpuscle. As mentioned earlier, these glomerular capillaries filter the blood based on particle size. After passing through the renal corpuscle, the capillaries form a second arteriole, the efferent arteriole (see Figure 5.4). As the glomerular filtrate progresses through the nephron, these capillary networks recover most of the solutes and water, and return them to the circulation. Since a capillary bed (the glomerulus) drains into a vessel that in turn forms a second capillary bed, the definition of a portal system is met. This is the only portal system in which an arteriole is found between the first and second capillary beds. (Portal systems also link the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary, and the blood vessels of the digestive viscera to the liver.

Ureter(s)

The kidneys and ureters are completely retroperitoneal, and the bladder has a peritoneal covering only over the dome. As urine is formed, it drains into the calyces of the kidney, which merge to form the funnel-shaped renal pelvis in the hilum of each kidney. The hilum narrows to become the ureter of each kidney. As urine passes through the ureter, it does not passively drain into the bladder but rather is propelled by waves of peristalsis. The ureters are approximately 30 cm long. The muscular layer of the ureter creates the peristaltic contractions to move the urine into the bladder without the aid of gravity.

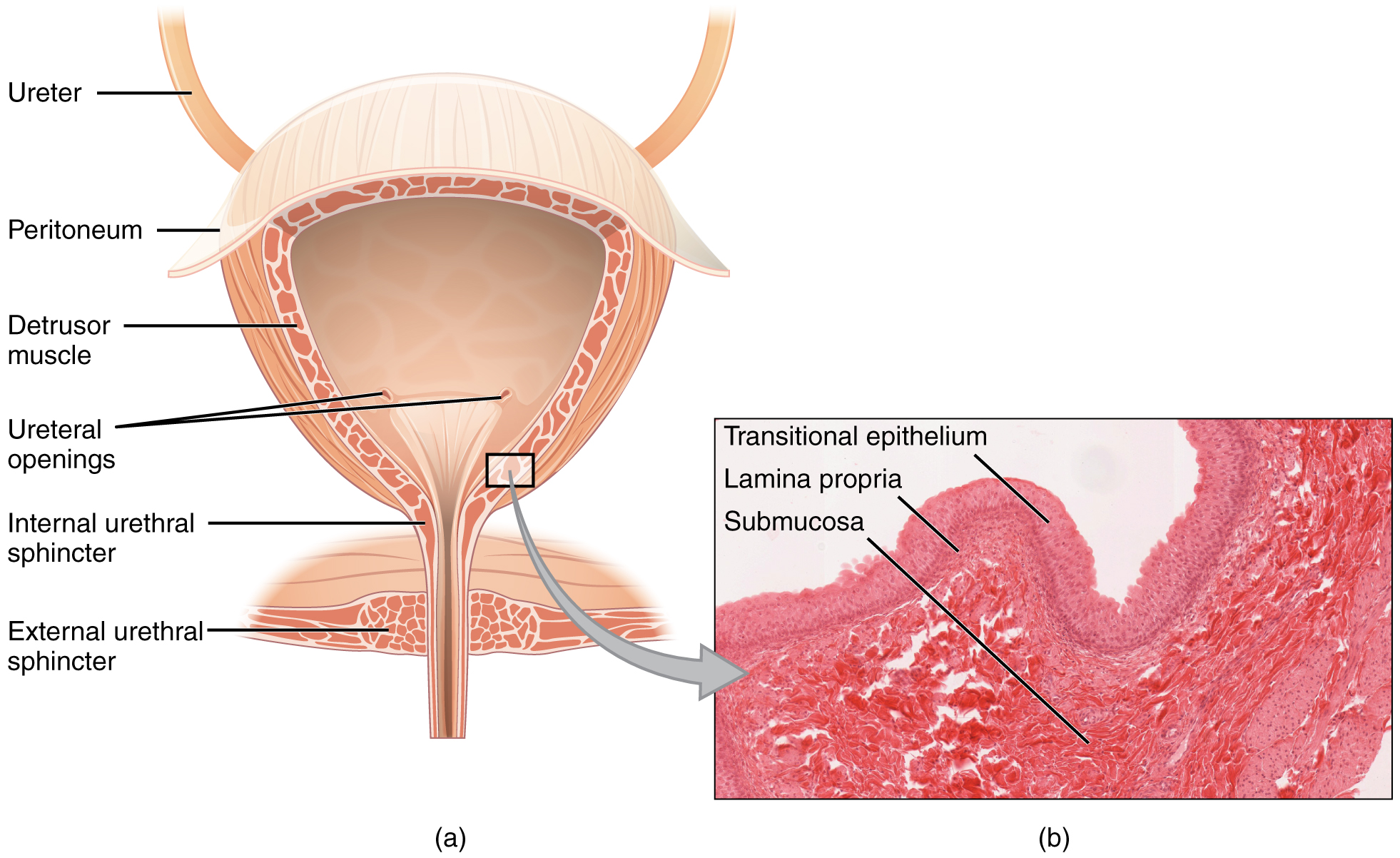

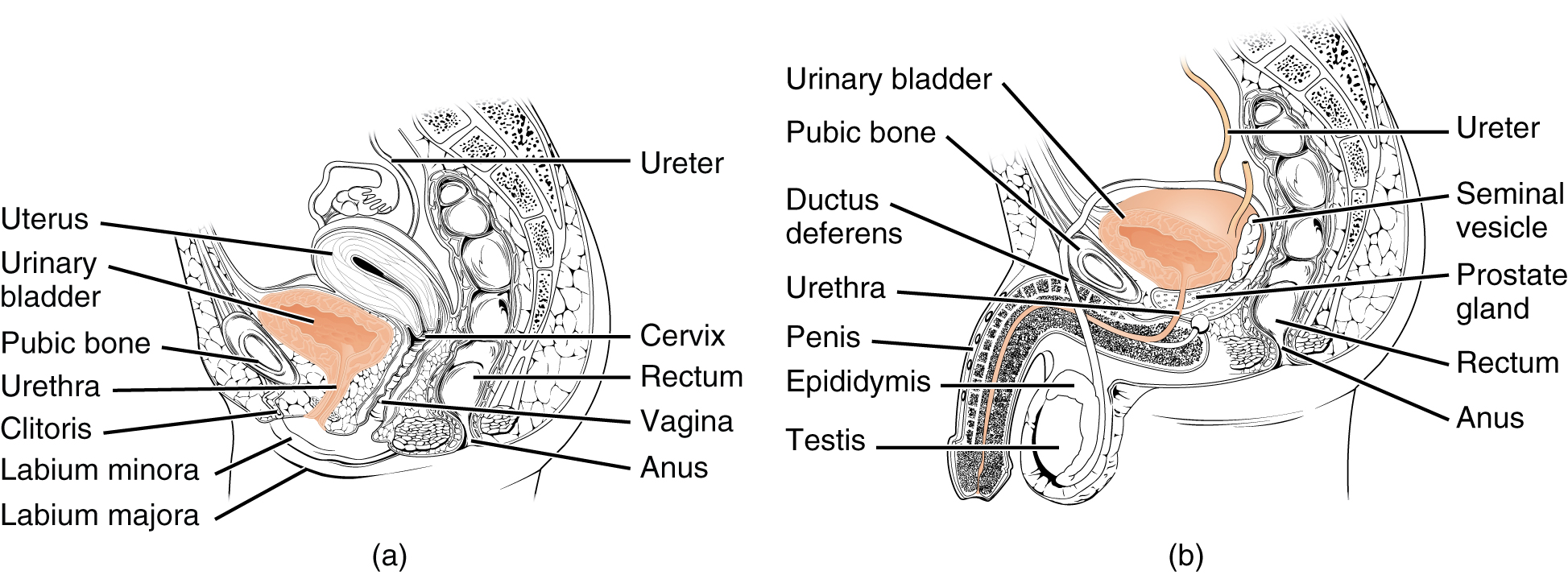

Bladder

The urinary bladder collects urine from both ureters (see Figure 5.5). The bladder lies anterior to the uterus in females, posterior to the pubic bone and anterior to the rectum. During late pregnancy, its capacity is reduced due to compression by the enlarging uterus, resulting in increased frequency of urination. In males, the anatomy is similar, minus the uterus, and with the addition of the prostate inferior to the bladder. The bladder is partially retroperitoneal (outside the peritoneal cavity) with its peritoneal-covered “dome” projecting into the abdomen when the bladder is distended with urine.

Urethra

The urethra transports urine from the bladder to the outside of the body for disposal. The urethra is the only urologic organ that shows any significant anatomic difference between males and females; all other urine transport structures are identical (see Figure 5.6).

Voiding is regulated by an involuntary autonomic nervous system-controlled internal urinary sphincter, consisting of smooth muscle and voluntary skeletal muscle that forms the external urinary sphincter below it.

Micturition Reflex

Micturition is a less-often used, but proper term for urination or voiding. It results from an interplay of involuntary and voluntary actions by the internal and external urethral sphincters. When bladder volume reaches about 150 ml (5 ounces), an urge to void is sensed but is easily overridden. Voluntary control of urination relies on consciously preventing relaxation of the external urethral sphincter to maintain urinary continence. As the bladder fills, subsequent urges become harder to ignore. Ultimately, voluntary constraint fails with resulting incontinence, which will occur as bladder volume approaches 300 to 400 ml (10 to 13 oz).

- Normal micturition is a result of stretch receptors in the bladder wall that transmit nerve impulses to the sacral region of the spinal cord to generate a spinal reflex. The resulting parasympathetic neural outflow causes contraction of the detrusor muscle and relaxation of the involuntary internal urethral sphincter.

- At the same time, the spinal cord inhibits somatic motor neurons, resulting in the relaxation of the skeletal muscle of the external urethral sphincter.

- The micturition reflex is active in infants but with maturity, children learn to override the reflex by asserting external sphincter control, thereby delaying voiding (potty training). This reflex may be preserved even in the face of spinal cord injury that results in paraplegia or quadriplegia. However, relaxation of the external sphincter may not be possible in all cases, and therefore, periodic catheterization may be necessary for bladder emptying.

Concept Check

- Describe two organs or structures essential to the urinary system.

- Identify the structure within the kidneys which filters blood.

- Name a commonly used term for the micturition reflex.

Anatomy Labeling Activity

Physiology (Function) of the Urinary System

- Remove waste products and medicines from the body

- Balance the body’s fluids

- Balance a variety of electrolytes

- Release hormones to control blood pressure

- Release a hormone to control red blood cell production

- Help with bone health by controlling calcium and phosphorus

Having reviewed the anatomy of the urinary system now is the time to focus on physiology. You will discover that different parts of the nephron utilize specific processes to produce urine: filtration, reabsorption, and secretion. You will learn how each of these processes works and where they occur along the nephron and collecting ducts. The physiologic goal is to modify the composition of the plasma and, in doing so, produce the waste product urine.

Nephrons: The Functional Unit

Nephrons take a simple filtrate of the blood and modify it into urine. Many changes take place in the different parts of the nephron before urine is created for disposal. The term “forming urine” will be used hereafter to describe the filtrate as it is modified into true urine. The principal task of the nephron population is to balance the plasma to homeostatic set points and excrete potential toxins in the urine. They do this by accomplishing three principle functions—filtration, reabsorption, and secretion. They also have additional secondary functions that exert control in three areas: blood pressure (via the production of renin), red blood cell production (via the hormone EPO), and calcium absorption (via the conversion of calcidiol into calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D).

Collecting Ducts

The collecting ducts are continuous with the nephron but are not technically part of it. In fact, each duct collects filtrate from several nephrons for final modification. Collecting ducts merge as they descend deeper in the medulla to form about 30 terminal ducts, which empty at a papilla.

Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR)

The volume of filtrate formed by both kidneys per minute is termed the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The heart pumps about 5 L (169 fluid ounces) of blood per min under resting conditions. Approximately 20 percent or one liter enters the kidneys to be filtered. On average, this liter results in the production of about 125 mL/min filtrate produced in men (range of 90 to 140 mL/min) and 105 mL/min filtrate produced in women (range of 80 to 125 mL/min). This amount equates to a volume of about 180 L/day in men and 150 L/day in women. Ninety-nine percent of this filtrate is returned to the circulation by reabsorption so that only about 1–2 liters of urine are produced per day.

GFR is influenced by the hydrostatic pressure and colloid osmotic pressure on either side of the capillary membrane of the glomerulus. Recall that filtration occurs as pressure forces fluid and solutes through a semipermeable barrier with the solute movement constrained by particle size. Hydrostatic pressure is the pressure produced by a fluid against a surface. If you have fluid on both sides of a barrier, both fluids exert pressure in opposing directions. The net fluid movement will be in the direction of the lower pressure. Osmosis is the movement of solvent (water) across a membrane that is impermeable to a solute in the solution. This creates osmotic pressure which will exist until the solute concentration is the same on both sides of a semipermeable membrane. As long as the concentration differs, water will move. Glomerular filtration occurs when glomerular hydrostatic pressure exceeds the luminal hydrostatic pressure of Bowman’s capsule. There is also an opposing force, the osmotic pressure, which is typically higher in the glomerular capillary.

A proper concentration of solutes in the blood is important in maintaining osmotic pressure both in the glomerulus and systemically. There are disorders in which too much protein passes through the filtration slits into the kidney filtrate. This excess protein in the filtrate leads to a deficiency of circulating plasma proteins. In turn, the presence of protein in the urine allows it to hold more water in the filtrate and results in an increase in urine volume. Because there is less circulating protein, principally albumin, the osmotic pressure of the blood falls. Less osmotic pressure pulling water into the capillaries tips the balance towards hydrostatic pressure, which tends to push it out of the capillaries. The net effect is that water is lost from the circulation to interstitial tissues and cells. This “plumps up” the tissues and cells, a condition termed systemic edema.

Reabsorption and Secretion

The renal corpuscle filters the blood to create a filtrate that differs from blood mainly in the absence of cells and large proteins. From this point to the ends of the collecting ducts, the filtrate or forming urine is undergoing modification through secretion and reabsorption before true urine is produced. Here, some substances are reabsorbed, whereas others are secreted. Note the use of the term “reabsorbed.” All of these substances were “absorbed” in the digestive tract—99 percent of the water and most of the solutes filtered by the nephron must be reabsorbed. Water and substances that are reabsorbed are returned to the circulation by the peritubular and vasa recta capillaries.

Urinalysis

Urinalysis (urine analysis) often provides clues to renal disease. Normally, only traces of protein are found in urine, and when higher amounts are found, damage to the glomeruli is the likely basis. Unusually large quantities of urine may point to diseases like diabetes mellitus or hypothalamic tumors that cause diabetes insipidus. The color of urine is determined mostly by the breakdown products of red blood cell destruction (see Figure 5.7). The “heme” of hemoglobin is converted by the liver into water-soluble forms that can be excreted into the bile and indirectly into the urine. This yellow pigment is urochrome. Urine color may also be affected by certain foods like beets, berries, and fava beans. A kidney stone or a cancer of the urinary system may produce sufficient bleeding to manifest as pink or even bright red urine. Diseases of the liver or obstructions of bile drainage from the liver impart a dark “tea” or “cola” hue to the urine. Dehydration produces darker, concentrated urine that may also possess the slight odor of ammonia. Most of the ammonia produced from protein breakdown is converted into urea by the liver, so ammonia is rarely detected in fresh urine. The strong ammonia odor you may detect in bathrooms or alleys is due to the breakdown of urea into ammonia by bacteria in the environment. About one in five people detect a distinctive odor in their urine after consuming asparagus; other foods such as onions, garlic, and fish can impart their own aromas. These food-caused odors are harmless.

Urine volume varies considerably. The normal range is one to two liters per day. The kidneys must produce a minimum urine volume of about 500 mL/day to rid the body of wastes. Output below this level may be caused by severe dehydration or renal disease and is termed oliguria. The virtual absence of urine production is termed anuria. Excessive urine production is polyuria, which may be due to diabetes mellitus or diabetes insipidus. In diabetes mellitus, blood glucose levels exceed the number of available sodium-glucose transporters in the kidney, and glucose appears in the urine. The osmotic nature of glucose attracts water, leading to its loss in the urine. In the case of diabetes insipidus, insufficient pituitary antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release or insufficient numbers of ADH receptors in the collecting ducts means that too few water channels are inserted into the cell membranes that line the collecting ducts of the kidney. Insufficient numbers of water channels (aquaporins) reduce water absorption, resulting in high volumes of very dilute urine.

Concept Check

- Contrast the following terms: oliguria, anuria and polyuria. What are the differences between these terms as they describe urinary output?

- Explain how urine color varies based on food consumed and/or hydration levels.

Endocrine Urinary Function

Several hormones have specific, important roles in regulating kidney function. They act to stimulate or inhibit blood flow. Some of these are endocrine, acting from a distance, whereas others are paracrine, acting locally.

Diuretics and Fluid Volume

A diuretic is a compound that increases urine volume. Three familiar drinks contain diuretic compounds: coffee, tea, and alcohol. The caffeine in coffee and tea works by promoting vasodilation in the nephron, which increases GFR. Alcohol increases GFR by inhibiting ADH release from the posterior pituitary, resulting in less water recovery by the collecting duct. In cases of high blood pressure, diuretics may be prescribed to reduce blood volume and, thereby, reduce blood pressure. The most frequently prescribed anti-hypertensive diuretic is hydrochlorothiazide.

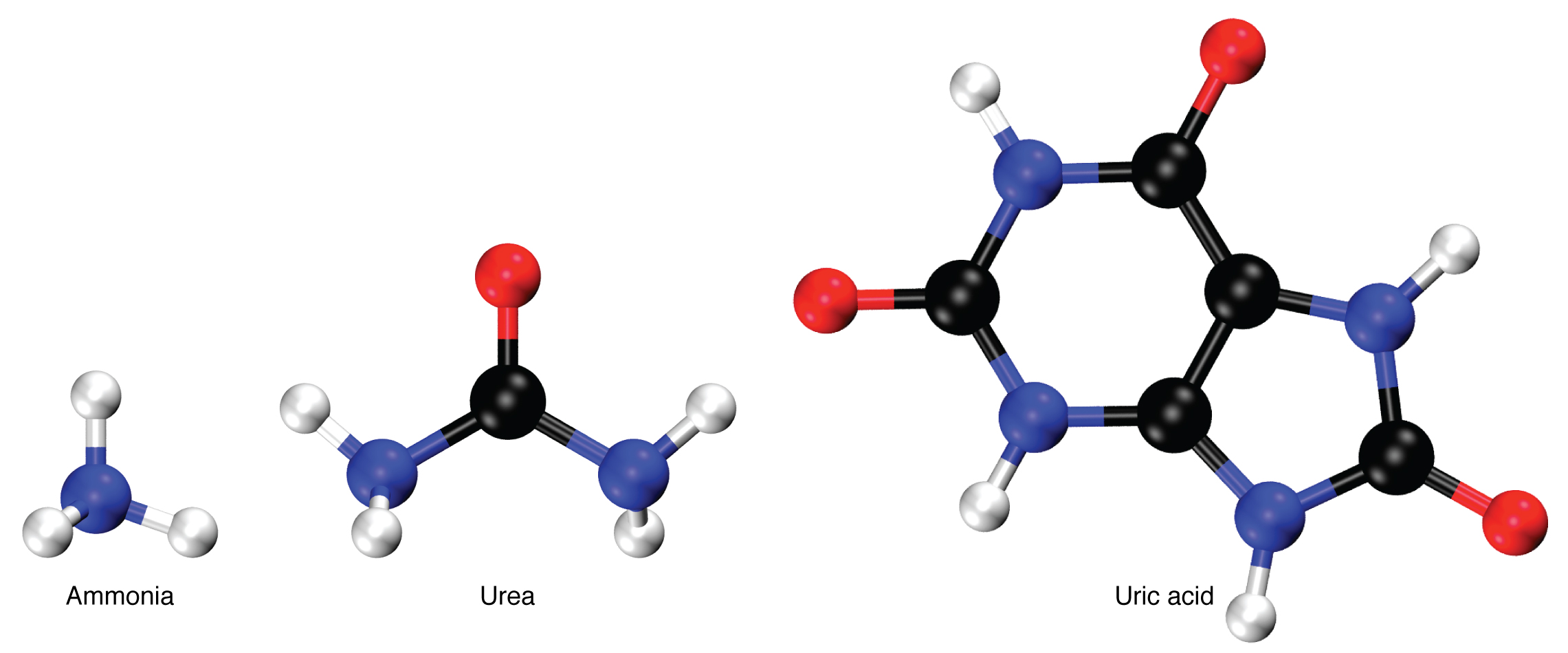

Regulation of Nitrogen Wastes

Nitrogen wastes are produced by the breakdown of proteins during normal metabolism. Proteins are broken down into amino acids, which in turn are deaminated by having their nitrogen groups removed. Deamination converts the amino (NH2) groups into ammonia (NH3), ammonium ion (NH4+), urea, or uric acid (Figure 5.8). Ammonia is extremely toxic, so most of it is very rapidly converted into urea in the liver. Human urinary wastes typically contain primarily urea with small amounts of ammonium and very little uric acid.

Watch the video: The Urinary System (7 minutes)

Urinary System Medical Terms not Easily Broken into Word Parts

Urinary System Abbreviations

Many terms and phrases related to the urinary system are abbreviated.

Learn these common abbreviations by expanding the list below.

Medical Specialties

Urologist

A urologist is a medical specialist involved in the diagnosis and treatment of urinary and male genitourinary system conditions, disorders, and diseases such as prostate disease, renal and bladder dysfunctions, and others (Watson, 2021).

Test Yourself

Use these practice activities to review the concepts in this chapter. If you prefer, there is a printable version of these activities.

Identify meanings of key word components of the urinary system.

Label each word part by using the following abbreviations.

Apply the rules of medical language to pronounce, break into word parts, and define the following terms.

Practice pronouncing and defining these medical terms that are not easily broken into word parts.

Practice pronouncing and defining these commonly abbreviated terms.

Label the following urinary system bladder anatomy.

Test your knowledge by answering the questions below.

References

American Urological Association. (2021, November 17). Why Urology?. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/2019-01/urology-e.pdf

Cleveland Clinic. (2019, May 22). Hydronephrosis. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15417-hydronephrosis

Mayo Clinic. (2020). Urology Overview. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/urology/sections/overview/ovc-20336015

Watson, Stephanie. (Updated 2018, September 29). What is a Urologist? https://www.healthline.com/health/what-is-a-urologist

Chapter Attributions

This chapter was adapted by Jerry Casteel from “Urinary System” by Stacey Grimm; Coleen Allee; Elaine Strachota; Laurie Zielinski; Traci Gotz; Micheal Randolph; and Heidi Belitz. Licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

Urinary System, Part 1: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #38 by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube license.

The Urinary System by Bozeman Science is licensed under the Standard YouTube license.

pH is a measure of how acidic or alkaline a substance is, as determined by the number of free hydrogen ions in the substance.

the minor component in a solution

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hormone produced by the kidney that promotes the formation of red blood cells by the bone marrow.

An enzyme secreted by the kidney that is part of a physiological system that regulates blood pressure.

biological process that results in stable equilibrium

Waste is eliminated from an organism. In vertebrates this is primarily carried out by the lungs, kidneys and skin.

instrument used to measure temperature

Excrete (waste matter)

unconsciously regulates

A muscle which forms a layer of the wall of the bladder

Relating to the equilibrium of liquids and the pressure exerted by liquid at rest.

A process by which molecules of a solvent tend to pass through a membrane from a less concentrated solution into a more concentrated one.

swelling

a region of the forebrain below the thalamus

The removal of an amino group from a molecule.