Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. It is the most common cause of dementia. In most people with Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. One in ten Americans aged 65 and older has Alzheimer’s disease.[1]

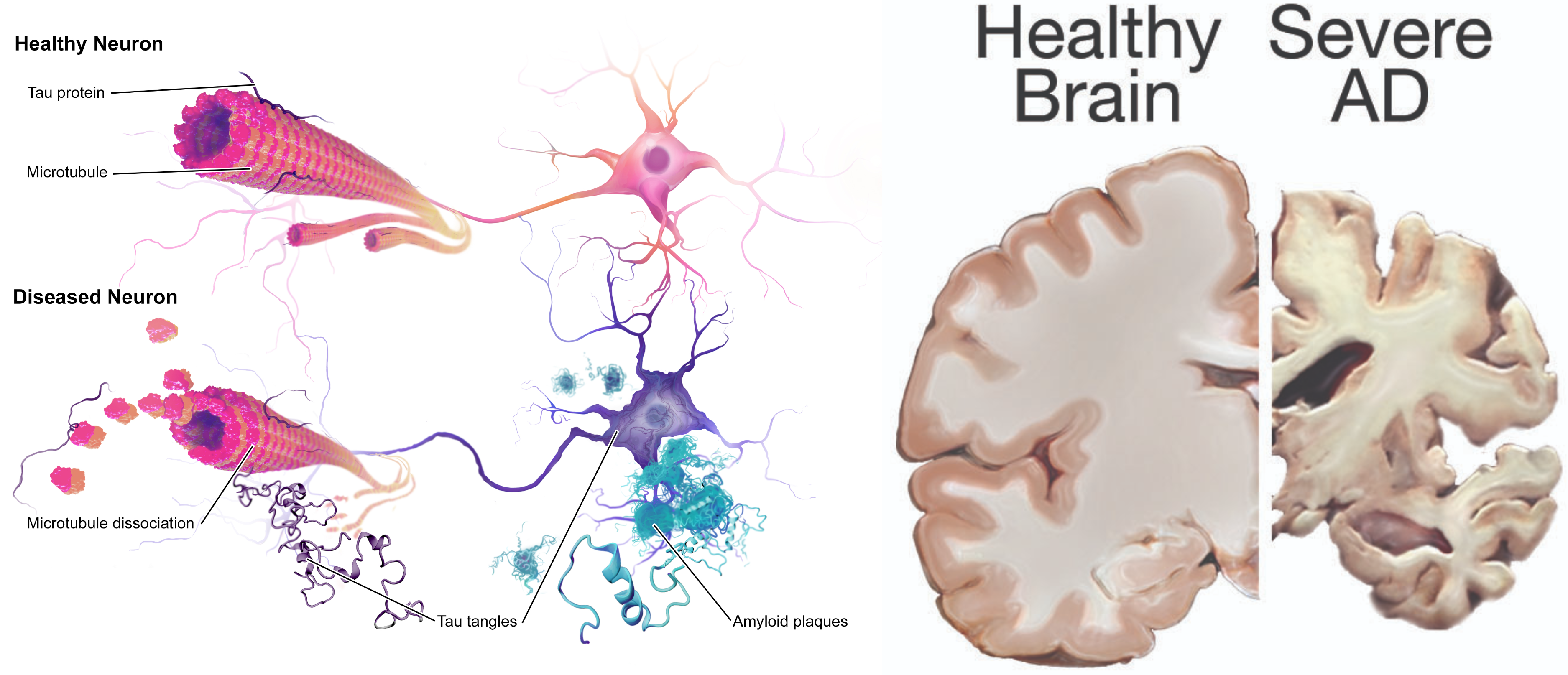

Scientists continue to unravel the complex brain changes involved in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. It is thought that changes in the brain may begin a decade or more before memory and other cognitive problems appear. Abnormal deposits of proteins form amyloid plaques and tau tangles throughout the brain. Previously healthy neurons stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. The damage initially appears to take place in the hippocampus and cortex, the parts of the brain essential in forming memories. As more neurons die, additional parts of the brain are affected and begin to shrink. By the final stage of Alzheimer’s, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.[2] See Figure 6.6[3] for an image of the changes occurring in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease.

View a video of the changes that occur in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease:[4]

Symptoms of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

There are ten symptoms of early Alzheimer’s disease:

- Forgetting recently learned information that disrupts daily life. This includes forgetting important dates or events, asking the same questions over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (e.g., reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own. This is different than a typical age-related change of sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. This includes changes in an individual’s ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. For example, they may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before. This is different from a typical age-related change of making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks. This includes trouble driving to a familiar location, organizing a grocery list, or remembering the rules of a favorite game. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of occasionally needing help to use microwave settings or to record a TV show.

- Confusion with time or place. This includes losing track of dates, seasons, and the passage of time. Individuals may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of forgetting the date or day of the week but figuring it out later.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Vision problems that include difficulty judging distance, determining color or contrast, or causing issues with balance or driving can be symptoms of Alzeheimer’s. This is different from a typical age-related change of blurred vision related to presbyopia or cataracts. (See the “Sensory Impairments” chapter for more information on common vision problems.)

- New problems with words in speaking or writing. Individuals with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble naming a familiar object, or use the wrong name (e.g., calling a “watch” a “hand-clock”). This is different from a typical age-related change of having trouble finding the right word.

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. A person with Alzheimer’s disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. They may accuse others of stealing, especially as the disease progresses. This is different from a typical age-related change of misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them.

- Decreased or poor judgment. Individuals with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money or pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean. This is different from a typical age-related change of making a bad decision or mistake once in a while, like neglecting to change the oil in the car.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. A person living with Alzheimer’s disease may experience changes in the ability to hold or follow a conversation. As a result, they may withdraw from hobbies, social activities, or other engagements. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite team or activity. This is different from a typical age-related change of sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations.

- Changes in mood and personality. Individuals living with Alzheimer’s may experience mood and personality changes. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, with friends, or when out of their comfort zone. This is different from a typical age-related change of developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.[5]

Three Stages of Dementia

There are three stages of dementia: early, moderate, and advanced. Early stages of dementia include the ten symptoms previously discussed. Clients with moderate dementia require additional assistance with reminders to eat, wash, and use the restroom. They may not recognize family and friends. Behavioral symptoms such as wandering, getting lost, hallucinations, delusions, and repetitive behavior may occur. Clients living at home may engage in risky behavior, such as leaving the house in clothing inappropriate for weather conditions or leaving on the stove burners. Clients with advanced dementia require full assistance in washing, dressing, eating, and toileting. They often have urinary and bowel incontinence. Their gait becomes shuffled or unsteady. There may be increased aggressive behavior, disinhibition, or inappropriate laughing. Eventually they have difficulty eating, swallowing, and speaking, and seizures may develop.[6] See Figure 6.7[7] of a client with dementia requiring assistance with dressing.

There is no single diagnostic test that can determine if a person has Alzheimer’s disease. Health care providers use a client’s medical history, mental status tests, physical and neurological exams, and diagnostic tests to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia. During the neurological exam, reflexes, coordination, muscle tone and strength, eye movement, speech, and sensation are tested.

Mental status testing evaluates memory, thinking, and simple problem-solving abilities. Some tests are brief, whereas others can be more time-intensive and complex. These tests give an overall sense of whether a person is aware of their symptoms; knows the date, time, and place where they are; can remember a short list of words; and if they can follow instructions and do simple calculations. The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and Mini-Cog test are two commonly used assessments.

During the MMSE, a health professional asks a client a series of questions designed to test a range of everyday mental skills. The maximum MMSE score is 30 points. A score of 20 to 24 suggests mild dementia, 13 to 20 suggests moderate dementia, and less than 12 indicates severe dementia. On average, the MMSE score of a person with Alzheimer’s declines about two to four points each year.

During the Mini-Cog, a person is asked to complete two tasks: remember and then later repeat the names of three common objects and draw a face of a clock showing all 12 numbers in the right places with the time indicated as specified by the examiner. The results of this brief test determine if further evaluation is needed. In addition to assessing mental status, the health care provider evaluates a person’s sense of well-being to detect depression or other mood disorders that can cause memory problems, loss of interest in life, and other symptoms that can overlap with dementia.

Diagnostic testing for Alzheimer’s disease may include structural imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). These tests are primarily used to rule out other conditions that can cause symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s but require different treatment. For example, structural imaging can reveal brain tumors, evidence of strokes, damage from head trauma, or a buildup of fluid in the brain.[8]

Treatments

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, there are medications to help lessen symptoms of memory loss and confusion and interventions to manage common symptomatic behaviors.

Medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two types of medications, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, to treat the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (memory loss, confusion, and problems with thinking and reasoning). As Alzheimer’s progresses, brain cells die and connections among cells are lost, causing cognitive symptoms to worsen. While current medications cannot stop the damage Alzheimer’s causes to brain cells, they may help lessen or stabilize symptoms for a limited time by affecting certain chemicals involved in carrying messages among the brain’s nerve cells. Sometimes both types of medications are prescribed together.

Cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed to treat early to moderate symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease related to memory, thinking, language, judgment, and other thought processes. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that is vital for learning and memory. It supports communication among nerve cells by keeping acetylcholine high and delays or slows the worsening of symptoms. Effectiveness varies from person to person, and the medications are generally well-tolerated. If side effects occur, they commonly include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and increased frequency of bowel movements. These three cholinesterase inhibitors are commonly prescribed:

- Donepezil (Aricept), approved to treat all stages of Alzheimer’s disease

- Galantamine (Razadyne), approved for mild-to-moderate stages

- Rivastigmine (Exelon), approved for mild-to-moderate stages

Memantine (Namenda) and a combination of memantine and donepezil (Namzaric) are approved by the FDA for treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s. Memantine is prescribed to improve memory, attention, reasoning, language, and the ability to perform simple tasks. Memantine regulates the activity of glutamate, a chemical involved in information processing, storage, and retrieval. It improves mental function and the ability to perform daily activities for some people, but it can cause side effects, including headache, constipation, confusion, and dizziness.

Other medications may be prescribed to treat specific symptoms of depression, anxiety, or psychosis. However, the decision to use an antipsychotic drug must be considered with extreme caution. Research has shown that these drugs are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia. The FDA has ordered manufacturers to label such drugs with a “Boxed” warning about their risks and a reminder that they are not approved to treat dementia symptoms. Individuals with dementia should use antipsychotic medications only under one of the following conditions:

- Behavioral symptoms are due to mania or psychosis.

- The symptoms present a danger to the person or others.

- The person is experiencing inconsolable or persistent distress, a significant decline in function, or substantial difficulty receiving needed care.

Antipsychotic medications should not be used to sedate or restrain persons with dementia. The minimum dosage should be used for the minimum amount of time possible, and nurses should carefully monitor for adverse side effects and report them to the health care provider.[9]

Interventions for Symptomatic Behavior

Many people find the behavioral changes caused by Alzheimer’s disease to be the most challenging and distressing effect of the disease. The chief cause of behavioral symptoms is the progressive deterioration of brain cells. However, medication, environmental influences, and some medical conditions can also cause symptoms or make them worse.

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, people may experience behavior and personality changes, such as irritability, anxiety, and depression. In later stages, other symptoms may occur, including the following:

- Aggression and anger

- Anxiety and agitation

- General emotional distress

- Physical or verbal outbursts

- Restlessness, pacing, or shredding paper or tissues

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that are not really there)

- Delusions (firmly held beliefs in things that are not true)

- Sleep issues and sundowning

Sundowning is restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that typically begins or worsens as daylight begins to fade and can continue into the night, making it hard for clients with Alzheimer’s to sleep. Being too tired can increase late-afternoon and early-evening restlessness. Tips to manage sundowning are as follows[10]:

- Take the person outside or expose them to bright light in the morning to reset their circadian rhythm.

- Do not plan too many activities during the day. A full schedule can be overtiring.

- Make early evening a quiet time of day. Play soothing music or ask a family member or friend to call during this time.

- Close the curtains or blinds at dusk to minimize shadows and the confusion they may cause.

- Reduce noise, clutter, or the number of people in the room.

- Do not serve coffee, cola, or other drinks with caffeine late in the day.

Aggressive Behaviors

Aggressive behaviors may be verbal or physical. They can occur suddenly, with no apparent reason, or result from a frustrating situation. While aggression can be hard to cope with, understanding this is a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and the person with Alzheimer’s or dementia is not acting this way on purpose can help. See Figure 6.8[11] for an image of a resident with dementia demonstrating aggressive verbal behavior.

Aggression can be caused by many factors including physical discomfort, environmental factors, and poor communication. If the person with Alzheimer’s is aggressive, consider what might be contributing to the change in behavior.

Physical Discomfort

- Is the person able to let you know they are experiencing physical pain? It is not uncommon for persons with Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia to have chronic pain, urinary tract infections, or other conditions causing acute pain. Due to their loss of cognitive function, they are unable to articulate or identify the cause of physical discomfort and, therefore, may express it through physical aggression.

- Is the person tired because of inadequate rest or sleep?

- Is the person hungry or thirsty?

- Are medications causing side effects? Side effects are especially likely to occur when individuals are taking multiple medications for several health conditions.

Environmental Factors

- Is the person overstimulated by loud noises, an overactive environment, or physical clutter? Large crowds or being surrounded by unfamiliar people — even within one’s own home — can be overstimulating for a person with dementia.

- Does the person feel lost?

- What time of day is the person most alert? Most people function better during a certain time of day; typically, mornings are best. Consider the time of day when making appointments or scheduling activities. Choose a time when you know the person is most alert and best able to process new information or surroundings.

Poor Communication

- Are your instructions simple and easy to understand?

- Are you asking too many questions or making too many statements at once?

- Is the person picking up on your own stress or irritability?

Techniques for Response

There are many therapeutic methods for a nurse or caregiver to respond to aggressive behaviors displayed by a person with dementia. The following are some methods that can be used with aggressive behavior:

- Begin by trying to identify the immediate cause of the behavior. Think about what happened right before the reaction that may have triggered the behavior. Rule out pain as the cause of the behavior. Pain can trigger aggressive behavior for a person with dementia.

- Focus on the person’s feelings, not the facts. Look for the feelings behind the specific words or actions.

- Don’t get upset. Be positive and reassuring and speak slowly in a soft tone.

- Limit distractions. Examine the person’s surroundings, and adapt them to avoid future triggers.

- Implement a relaxing activity. Try music, massage, or exercise to help soothe the person.

- Shift the focus to another activity. The immediate situation or activity may have unintentionally caused the aggressive response, so try a different approach.

- Take a break if needed. If the person is in a safe environment and you are able, walk away and take a moment for emotions to cool.

- Ensure safety! Make sure you and the person are safe. Be aware of the location of the person’s hands and feet in the event they become combative and try to strike out, kick, or bite you. If these interventions do not successfully calm down the person, seek assistance from others. If it is an emergency situation, call 911 and be sure to tell the responders the person has dementia that causes them to act aggressively.

When educating caregivers about responding to aggressive behaviors, encourage them to share their experience with others, such as face-to-face support groups, where they can share response strategies they have tried and also get more ideas from other caregivers.

Anxiety and Agitation

A person with Alzheimer’s may feel anxious or agitated. They may become restless, causing a need to move around or pace or become upset in certain places or when focused on specific details. See Figure 6.9[12] for an illustration of an older adult feeling the need to move around. Anxiety and agitation can be caused by several medical conditions, medication interactions, or by any circumstances that worsen the person’s ability to think. Ultimately, the person with dementia is biologically experiencing a profound loss of their ability to negotiate new information and stimuli. It is a direct result of the disease. Situations that may lead to agitation can include moving to a new residence or nursing home; changes in environment, such as travel, hospitalization, or the presence of houseguests; changes in caregiver arrangements; misperceived threats; or fear and fatigue resulting from trying to make sense out of a confusing world.

Interventions to prevent and treat agitation include the following:

- Create a calm environment and remove stressors. This may involve moving the person to a safer or quieter place or offering a security object, rest, or privacy. Providing soothing rituals and limiting caffeine use are also helpful.

- Avoid environmental triggers. Noise, glare, and background distraction (such as having the television on) can act as triggers.

- Monitor personal comfort. Check for pain, hunger, thirst, constipation, full bladder, fatigue, infections, and skin irritation. Make sure the room is at a comfortable temperature. Be sensitive to the person’s fears, misperceived threats, and frustration with expressing what is wanted.

- Simplify tasks and routines.

- Find outlets for the person’s energy. The person may be looking for something to do. Provide an opportunity for exercise such as going for a walk or putting on music and dancing.

Techniques for Response

If a client with dementia becomes anxious or agitated, consider these potential interventions:

- Back off and ask permission before performing care tasks. Use calm, positive statements, slow down, add lighting, and provide reassurance. Offer guided choices between two options when possible. Focus on pleasant events and try to limit stimulation.

- Use effective language. When speaking, try phrases such as, “May I help you? Do you have time to help me? You’re safe here. Everything is under control. I apologize. I’m sorry that you are upset. I know it’s hard. I will stay with you until you feel better.”

- Listen to the person’s frustration. Find out what may be causing the agitation and try to understand.

- Check yourself. Do not raise your voice; show alarm or offense; or corner, crowd, restrain, criticize, ignore, or argue with the person. Take care not to make sudden movements out of the person’s view. Be aware of the client’s hands and feet in the event they strike out or kick at you.

If the person’s anxiety or agitation does not improve using these techniques, notify the provider to rule out physiological causes or medication-related side effects.

Hallucinations

When a person with dementia experiences hallucinations, they may see, hear, smell, taste, or feel something that isn’t there. Some hallucinations may be frightening, while others may involve ordinary visions of people, situations, or objects from the past. Alzheimer’s and other dementias are not the only cause of hallucinations. Other causes of hallucinations include schizophrenia; physical problems, such as kidney or bladder infections, dehydration, or intense pain; alcohol or drug abuse; eyesight or hearing problems; and medications. See Figure 6.10[13] for an illustration of hallucinations experienced by a person with dementia.

If a person with dementia begins hallucinating, notify the health care provider to rule out other possible causes and to determine if medication is needed. It may also help to have the person’s eyesight or hearing checked. If these strategies fail and symptoms are severe, medication may be prescribed. While antipsychotic medications can be effective in some situations, they are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia and must be used carefully.

Techniques for Response

When responding to a client with dementia experiencing hallucinations, be cautious. First, assess the situation and determine whether the hallucination is a problem for the person or for you. Is the hallucination upsetting? Is it leading the person to do something dangerous? Is the sight of an unfamiliar face causing the person to become frightened? If so, react calmly and quickly with reassuring words and a comforting touch. Do not argue with the person about what they see or hear. If the behavior is not dangerous, there may not be a need to intervene.

- Offer reassurance. Respond in a calm, supportive manner. You may want to respond with, “Don’t worry. I’m here. I’ll protect you. I’ll take care of you.” Gentle patting may turn the person’s attention toward you and reduce the hallucination.

- Acknowledge the feelings behind the hallucination and try to find out what the hallucination means to the individual. You might want to say, “It sounds as if you’re worried” or “This must be frightening for you.”

- Use distractions. Suggest a walk or move to another room. Frightening hallucinations often subside in well-lit areas where other people are present. Try to turn the person’s attention to music, conversation, or activities they enjoy.

- Respond honestly. If the person asks you about a hallucination or delusion, be honest. For example, if they ask, “Do you see the spider on the wall?,” you can respond, “I know you see something, but I don’t see it.” This way you’re not denying what the person sees or hears and avoiding escalating their agitation.

- Modify the environment. Check for sounds that might be misinterpreted, such as noise from a television or an air conditioner. Look for lighting that casts shadows, reflections, or distortions on the surfaces of floors, walls, and furniture. Turn on lights to reduce shadows. Cover mirrors with a cloth or remove them if the person thinks that he or she is looking at a stranger.

Sundowning

Sundowning is increased confusion, anxiety, agitation, pacing, and disorientation in clients with dementia that typically begins at dusk and continues throughout the night. Although the exact cause of sundowning and sleep disorders in people with Alzheimer’s disease is unknown, these changes result from the disease’s impact on the brain. There are several factors that may contribute to sleep disturbances and sundowning:

- Mental and physical exhaustion from a full day trying to keep up with an unfamiliar or confusing environment.

- An upset in the “internal body clock,” causing a biological mix-up between day and night.

- Reduced lighting causing shadows and misinterpretation is seen, causing agitation.

- Nonverbal behaviors of others, especially if stress or frustration is present.

- Disorientation due to the inability to separate dreams from reality when sleeping.

- Decreased need for sleep, a common condition among older adults.[14]

There are several interventions that nurses and caregivers can implement to help manage sleep issues and sundowning:

- Promote plenty of rest.

- Encourage a regular routine of waking up, eating meals, and going to bed.

- When possible and appropriate, include walks or time outside in the sunlight.

- Make notes about what happens before sundowning events and try to identify triggers.

- Reduce stimulation during the evening hours (e.g., TV, doing chores, loud music, etc.). These distractions may add to the person’s confusion.

- Offer a larger meal at lunch and keep the evening meal lighter.

- Keep the home environment well-lit in the evening. Adequate lighting may reduce the person’s confusion.

- Do not physically restrain the person; it can make agitation worse.

- Try to identify activities that are soothing to the person, such as listening to calming music, looking at photographs, or watching a favorite movie.

- Take a walk with the person to help reduce their restlessness.

- Consider the best times of day for administering medication; consult with the prescribing provider or pharmacist as needed.

- Limit daytime naps if the person has trouble sleeping at night.

- Reduce or avoid alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine that can affect the ability to sleep.

- Discuss the situation with the provider when behavioral interventions and environmental changes do not work. Additional medications may be prescribed.

Caregiver Role Strain

Eighty-three percent of the help provided to people living with dementia in their homes in the United States comes from family members, friends, or other unpaid caregivers. Approximately one quarter of dementia caregivers are also “sandwich generation” caregivers — meaning that they care not only for an aging parent, but also for children under age 18. Dementia can take a devastating toll on caregivers. Compared with caregivers of people without dementia, twice as many caregivers of people with dementia indicate substantial emotional, financial, and physical difficulties.[15] See Figure 6.11[16] of an image of a caregiver daughter caring for her mother with dementia.

The caregivers of clients with dementia frequently report experiencing high levels of stress that often eventually impact their health and well-being. Nurses should monitor caregivers for these symptoms of stress:

- Denial about the disease and its effect on the person who has been diagnosed. For example, the caregiver might say, “I know Mom is going to get better.”

- Anger at the person with Alzheimer’s or frustration that they can’t do the things they used to be able to do. For example, the caregiver might say, “He knows how to get dressed — he’s just being stubborn.”

- Social withdrawal from friends and activities. For example, the caregiver may say, “I don’t care about visiting with my friends anymore.”

- Anxiety about the future and facing another day. For example, the caregiver might say, “What happens when he needs more care than I can provide?”

- Depression or decreased ability to cope. For example, the caregiver might say, “I just don’t care anymore.”

- Exhaustion that makes it difficult to complete necessary daily tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I’m too tired to prepare meals.”

- Sleeplessness caused by concerns. For example, the caregiver might say, “What if she wanders out of the house or falls and hurts herself?”

- Irritability, moodiness, or negative responses.

- Lack of concentration that makes it difficult to perform familiar tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I was so busy; I forgot my appointment.”

- Health problems that begin to take a mental and physical toll. For example, the caregiver might say, “I can’t remember the last time I felt good.”

Nurses should monitor for these signs of caregiver stress and provide information about community resources. (See additional information about community resources below.) Caregivers should be encouraged to take good care of themselves by visiting their health care provider, eating well, exercising, and getting plenty of rest. It is helpful to remind caregivers that “taking care of yourself and being healthy can help you be a better caregiver.” Teach them relaxation techniques, such as relaxation breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, visualization, and meditation.

Caregivers should also be educated about additional care options, such as adult day care, respite care, residential facilities, or hospice care. Adult day care centers offer people with dementia and other chronic illnesses the opportunity to be social and to participate in activities in a safe environment, while also giving their caregivers the opportunity to work, run errands, or take a break. Respite care can be provided at home (by a volunteer or paid service) or in a care setting, such as adult day care or residential facility, to provide the caregiver a much-needed break. If the person with Alzheimer’s or other dementia prefers a communal living environment or requires more care than can be safely provided at home, a residential facility may be the best option for providing care. Different types of facilities provide different levels of care, depending on the person’s needs. Hospice care is a type of care selected by clients who are terminally ill and whose health care provider has determined they are expected to live six months or less. It focuses on providing comfort and dignity at the end of life with supportive services that can be of great benefit to people in the final stages of dementia and their families.

Read about alternative care options and caregiver support at the Alzheimer Association web page.

Community Resources

Local Alzheimer’s Association chapters can connect families and caregivers with the resources they need to cope with the challenges of caring for individuals with Alzheimer’s. View examples of resources provided by the Alzheimer’s Association in the following box.

Find an Alzheimer’s Association chapter in your community by visiting the Find Your Local Chapter web page.

The Alzheimer’s Association 24/7 Helpline (800.272.3900) is available around the clock, 365 days a year. Through this free service, specialists and master’s-level clinicians offer confidential support and information to people living with dementia, caregivers, families, and the public.

The Alzheimer’s Association has a free virtual library web page devoted to resources that increase knowledge about Alzheimer’s and other dementias.[17]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2019, May 22). Alzheimer’s disease fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet ↵

- “Alzheimers_Disease.jpg” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and “24239522109_6b061a9d69_o.jpg” by NIH Image Gallery is licensed under CC0 ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2017, August 23). How Alzheimer’s changes the brain [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/0GXv3mHs9AU ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- “civilian-service-63616_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). Tips for coping with sundowning. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/tips-coping-sundowning ↵

- “5012292106_507e008c7a_o.jpg” by borosjuli is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “old-63622_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- lewy-body-dementia-2965713_960_720.jpg” by Jetiveri is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- “My_mum_ill_with_dementia_with_me.png” by MariaMagdalens is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

A review process to determine if an agency meets the defined standards of quality determined by the accrediting body.

Now that we have discussed basic concepts and the nursing process related to the grieving process, let’s discuss more details regarding providing palliative care. Nurses provide palliative care whenever caring for clients with chronic disease. As the disease progresses and becomes end-stage, the palliative care they provide becomes even more important. As previously discussed in the "Basic Concepts" section, palliative care is client and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care occurs throughout the continuum of care and involves the interdisciplinary team collaboratively addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and facilitating client autonomy, access to information, and choice.”[1]

Providing care at the end of life is similar for clients with a broad variety of medical diagnoses. It addresses multiple dimensions of care, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects:

- Physical: Functional ability, strength/fatigue, sleep/rest, nausea, appetite, constipation, and pain

- Psychological: Anxiety, depression, enjoyment/leisure, pain, distress, happiness, fear, and cognition/attention

- Social: Financial burden, caregiver burden, roles/relationships, affection, and appearance

- Spiritual: Hope, suffering, the meaning of pain, religiosity, and transcendence[2]

The interdisciplinary team manages pain and other symptoms, assists with difficult medical decisions, and provides additional support to clients, family members, and caregivers. Nurses have the opportunity to maintain hope for clients and family members by providing excellent physical, psychosocial, and spiritual palliative care. Nursing interventions begin immediately after the initial medical diagnosis and continue throughout the continuum of care until the end of life. As a client approaches end-of-life care, nursing interventions include the following:

- Eliciting the client’s goals for care

- Listening to the client and their family members

- Communicating with members of the interdisciplinary team and advocating for the client’s wishes

- Managing end-of-life symptoms

- Encouraging reminiscing

- Facilitating participating in religious rituals and spiritual practices

- Making referrals to chaplains, clergy, and other spiritual support[3]

While providing palliative care, it is important to remain aware that some things cannot be “fixed”:

- We cannot change the inevitability of death.

- We cannot change the anguish felt when a loved one dies.

- We must all face the fact that we, too, will die.

- The perfect words or interventions rarely exist, so providing presence is vital.[4]

The Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin contains excellent resources for nurses providing care for seriously ill clients.

View the "Fast Facts" page for extensive information about palliative care and end-of-life topics.

Management of Common Symptoms

Many clients with serious, life-limiting illnesses have common symptoms that the nurse can assess, prevent, and manage to optimize their quality of life. These symptoms include pain, dyspnea, cough, anorexia and cachexia, constipation, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, depression, anxiety, cognitive changes, fatigue, pressure injuries, seizures, and sleep disturbances. Good symptom management improves quality of life and functioning at all states of chronic illness. Nurses play a critical role in recognizing these symptoms and communicating them to the interdisciplinary team for optimal management. The plan of care should always be based on the client’s goals and their definition of quality of life.[5] These common symptoms are discussed in the following subsections.

Pain

Pain is frequently defined as “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever they say it does.”[6] When a client is unable to verbally report their pain, it is important to assess nonverbal and behavioral indicators of pain. The goal is to balance the client’s desire for pain relief, along with their desire to manage side effects and oversedation. There are many options available for analgesics. Reassure a client that reaching their goal of satisfactory pain relief is achievable. Read more about pain management in the “Comfort” chapter. See Figure 17.18[7] for an image illustrating a client experiencing pain.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a subjective experience of breathing discomfort and is the most reported symptom by clients with life-limiting illness. Dyspnea can be extremely frightening. Assessing dyspnea can be challenging because the client’s respiratory rate and oxygenation status do not always correlate with the symptom of breathlessness.[8] See Figure 17.19[9] for an image of a client depicting chest pain and dyspnea.

When assessing dyspnea, include the following components[10]:

- Ask the client to rate the severity of their breathlessness on a scale of 0-10

- Assess their ability to speak in sentences, phrases, or words

- Assess the client’s anxiety

- Observe respiratory rate and effort

- Measure oxygenation status (i.e., pulse oximetry or ABG)

- Auscultate lung sounds

- Assess for the presence of chest pain or other pain

- Assess factors that improve or worsen breathlessness

- Evaluate the impact of dyspnea on functional status and quality of life

If you suspect that new dyspnea is caused by an acute condition, report assessment findings immediately to a health care provider. Remember that acute illnesses are still addressed and treated for clients receiving palliative care. However, in end-stage disease, dyspnea can be a chronic condition that is treated with pharmacological and nonpharmacological management. Relatively small doses of opioids can be used to improve dyspnea while having little impact on respiratory status or a client’s life expectancy. Opioids help dilate pulmonary blood vessels, allowing more blood to flow to the lungs and lessening the work of breathing. The dosage should be titrated to the client’s desired goals for relief of dyspnea without over sedation.

Nonpharmacological interventions for dyspnea include pursed-lip breathing, energy conservation techniques, fans and open windows to circulate air, elevation of the client bed, placing the client in a tripod position, and relaxation techniques such as music and a calm, cool environment. Health teaching can also reduce anxiety.[11] Read more about nonpharmacological interventions for dyspnea in the “Oxygenation” chapter.

Cough

A cough can be frustrating and debilitating for a client, causing pain, fatigue, vomiting, and insomnia. See Figure 17.20[12] for an image of a person depicting a chronic cough. Coughing is frequently present in advanced diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF), cancer, and AIDS. Medications that can be used to control a cough are opioids, dextromethorphan, and benzonatate. Guaifenesin can be used to thin thick secretions, and anticholinergics (such as scopolamine) can be used for high-volume secretions.

Anorexia and Cachexia

Anorexia (loss of appetite or loss of desire to eat) and cachexia (wasting of muscle and adipose tissue due to lack of nutrition) are commonly found in advanced disease. See Figure 17.21[13] for an image of a client with cachexia. Weight loss is present in both conditions and is associated with decreased survival. Unfortunately, aggressive nutritional treatment does not improve survival or quality of life and can actually create more discomfort for the client as body systems begin to shut down as death approaches.[14]

Assessment of anorexia and cachexia focuses on understanding the client’s experience and concerns, as well as determining potentially reversible causes. Referral to a dietician may be needed. Read more about nutritional assessment in the “Nutrition” chapter.

Interventions for anorexia and cachexia should be individualized for each client with the goal being eating for pleasure for those at the end of life. Clients should be encouraged to eat their favorite foods, as well as select foods that are high in calories and easy to chew. Small, frequent meals with pleasing food presentation are important. Family members should be aware that odors associated with cooking can inhibit eating. The client may need to be moved away from the kitchen or cooking times separated from eating times.[15]

Medication may be prescribed to increase intake, such as mirtazapine or olanzapine. Prokinetics such as metoclopramide may be helpful in increasing gastric emptying. Medical marijuana or dronabinol may also be useful to stimulate appetite and reduce nausea. In some cases, enteral nutrition is helpful for clients who continue to have an appetite but cannot swallow.[16]

Health teaching for clients and family members about anorexia at the end of life is important. Nurses should be aware that many family members perceive eating as a way to “get better” and are distressed to see their loved one not eat. After listening respectfully to their concerns, explain that the client may feel more discomfort when forcing themselves to eat.

Constipation

Constipation is a frequent symptom in many clients at the end of life for many factors, such as low intake of food and fluids, use of opioids, chemotherapy, and impaired mobility. Constipation is defined as having less than three bowel movements per week. The client may experience associated symptoms such as rectal pressure, abdominal cramps, bloating, distension, and straining. See Figure 17.22[17] for an image of a client depicting symptoms of constipation.

The goal is to establish what is considered normal for each client and to have a bowel movement at least every 72 hours regardless of intake. Treatment includes a bowel regimen such as oral stool softeners (i.e., docusate) and a stimulant (i.e., sennosides). Rectal suppositories (i.e., bisacodyl) or enemas should be considered when oral medications are not effective, or the client can no longer tolerate oral medications.[18]

Read more about managing constipation in the “Elimination” chapter.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined as having more than three unformed stools in 24 hours. Diarrhea can be especially problematic for clients receiving chemotherapy, pelvic radiation, or treatment for AIDS because diarrhea is a common side effect of these treatments. It can cause dehydration, skin breakdown, and electrolyte imbalances and dramatically affect a person’s quality of life. It can also be a burden for caregivers due to frequent bathroom use or incontinence episodes.[19]

Early treatment of diarrhea includes promoting hydration with water or fluids that improve electrolyte status (i.e., sports drinks). Intravenous fluids may be required based on the client’s disease stage and goals for care. Medications such as loperamide, psyllium, and anticholinergic agents may also be prescribed to decrease the incidence of diarrhea.

Read more about managing diarrhea in the “Elimination” chapter.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea is common in advanced disease and is a dreaded side effect of many treatments for cancer. Assessment of nausea and vomiting should include the client’s history, effectiveness of previous treatment, medication history, frequency and intensity of episodes of nausea and vomiting, and activities that precipitate or alleviate nausea and vomiting.[20]

Nonpharmacological interventions for nausea include eating meals and fluids at room temperature, avoiding strong odors, avoiding high-bulk meals, using relaxation techniques, and listening to music therapy.[21] Aromatherapy using essential oils such as peppermint oil has been shown to significantly decrease the incidence of nausea and vomiting in hospitalized clients and those receiving chemotherapy.[22] Antiemetic medications, such as prochlorperazine and ondansetron, may be prescribed.

Read more information about managing nausea in the “Antiemetics” section of the Gastrointestinal chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Depression

Clients who have a serious life-threatening illness will normally experience sadness, grief, and loss, but there is usually some capacity for pleasure. Persistent feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation are not considered a normal part of the grief process and should be treated. Undertreated depression can cause a decreased immune response, decreased quality of life, and decreased survival time. Evaluation of depression requires interdisciplinary assessment and referrals to social work and psychiatry may be needed.[23]

Antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or citalopram, are generally prescribed as first-line treatment of depression. Other medication may be prescribed if these medications are not effective.

Nonpharmacological interventions for depression may include the following:

- Promoting and facilitating as much autonomy and control as possible.

- Encouraging client and family participation in care, thus promoting a sense of control and reducing feelings of helplessness.

- Reminiscing and life review to focus on life accomplishments and to promote closure and resolution of life events. See Figure 17.23[24] for an image of reminiscing with pictures.

- Grief counseling to assist clients and families in dealing with loss.

- Maximizing symptom management.

- Referring to counseling for those experiencing inability to cope.

- Assisting the client to draw on previous sources of strength, such as faith, religious rituals, and spirituality.

- Referring for cognitive behavioral techniques to assist with reframing negative thoughts into positive thoughts.

- Teaching relaxation techniques.

- Providing ongoing emotional support and “being present.”

- Reducing isolation.

- Facilitating spiritual support.[25]

A suicide assessment is critical for a client with depression. It is important for nurses to ask questions, such as these:

- Do you have interest or pleasure in doing things?

- Have you had thoughts of harming yourself?

- If yes, do you have a plan for doing so?

To destigmatize the questions, it is helpful to phrase them in the following way, “It wouldn’t be unusual for someone in your circumstances to have thoughts of harming themselves. Have you had thoughts like that?" Clients with immediate, precise suicide plans and resources to carry out this plan should be immediately evaluated by psychiatric professionals.[26]

Anxiety

Anxiety is a subjective feeling of apprehension, tension, insecurity, and uneasiness, usually without a known specific cause. It may be anticipatory. It is assessed along a continuum as mild, moderate, or severe. Clients with life-limiting illness will experience various degrees of anxiety due to various issues such as their prognosis, mortality, financial concerns, uncontrolled pain and other symptoms, and feelings of loss of control.[27]

Physical symptoms of anxiety include sweating, tachycardia, restlessness, agitation, trembling, chest pain, hyperventilation, tension, and insomnia. Cognitive symptoms include recurrent and persistent thoughts and difficulty concentrating. See Figure 17.24[28] for an illustration of anxiety.

Benzodiazepines (i.e., lorazepam) may be prescribed to treat anxiety. However, the nurse should assess for adverse effects such as oversedation, falls, and delirium, especially in the frail elderly.

Nonpharmacological interventions are crucial and include the following[29]:

- Maximizing symptom management to decrease stressors

- Promoting the use of relaxation and guided imagery techniques, such as breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and the use of audiotapes

- Referring for psychiatric counseling for those unable to cope with the experience of their illness

- Facilitating spiritual support by contacting chaplains and clergy

- Acknowledging client fears and using open-ended questions and active listening with therapeutic communication

- Identifying effective coping strategies the client has used in the past, as well as teaching new coping skills such as relaxation and guided imagery techniques

- Providing concrete information to eliminate fear of the unknown

- Encouraging the use of a stress diary that helps the client understand the relationship between situations, thoughts, and feelings

Cognitive Changes

Delirium is a common cognitive disorder in hospitals and palliative care settings. Delirium is an acute change in cognition and requires urgent management in inpatient care. Up to 90% of clients at the end of life will develop delirium in their final days and hours of life. Early detection of delirium can cause resolution if the cause is reversible.[30]

Symptoms of delirium include agitation, confusion, hallucinations, or inappropriate behavior. It is important to obtain information from the caregiver to establish a mental status baseline. The most common cause of delirium at end of life is medication, followed by metabolic insufficiency due to organ failure.[31]

Medications such as neuroleptics (i.e., haloperidol and chlorpromazine) or benzodiazepines may be prescribed to manage delirium symptoms, but it is important to remember that delirium can be caused by opioid toxicity. It may be helpful to request the presence of family to reorient the patient, as well as provide nonpharmacological interventions such as massage, distraction, and relaxation techniques.[32]

Read more about delirium in the “Cognitive Impairments” chapter.

Fatigue

Fatigue has been cited as the most disabling condition for clients receiving a variety of treatments in palliative care. Fatigue is defined as a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion that is not proportional to activity and interferes with usual functioning.[33] See Figure 17.25[34] for an image of an older client depicting fatigue.

The primary cause of fatigue is metabolic alteration related to chronic disease, but it can also be caused by anemia, infection, poor sleep quality, chronic pain, and medication side effects. Nonpharmacological interventions include energy conservation techniques.

Pressure Injuries

Clients at end of life are at risk for quickly developing pressure injuries for a variety of reasons, including decreased nutrition and altered mobility. Prevention is key and requires interventions such as promoting mobility, frequent repositioning, reducing moisture, and encouraging nutrition as appropriate.

The Kennedy Terminal Ulcer is a type of pressure injury that some clients develop shortly before death resulting from multiorgan failure. It usually starts on the sacrum and is shaped like a pear, butterfly, or horseshoe. It is red, yellow, black, or purple in color with irregular borders and progresses quickly. For example, the injury may be identified by a nurse at the end of a shift who says, “That injury was not present when I assessed the client this morning.”[35]

Read more about assessing, preventing, and treating pressure injuries in the “Integumentary” chapter.

Seizures

Seizures are sudden, abnormal, excessive electrical impulses in the brain that alter neurological functions such as motor, autonomic, behavioral, and cognitive function. A seizure can be caused by infection, trauma, brain injury, brain tumors, side effects of medications, metabolic imbalances, drug toxicities, and withdrawal from medications.[36]

Seizures can have gradual or acute onset and include symptoms such as mental status changes, motor movement changes, and sensory changes. Treatment is focused on prevention and limiting trauma that may occur during the seizure. Medications such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, benzodiazepines, or levetiracetam may be prescribed to prevent or manage seizure activity.[37]

Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances affect quality of life and can cause much suffering. It can be caused by poor pain and symptom management, as well as environmental disturbances. Nurses can promote improved sleep for inpatients by creating a quiet, calm environment, promoting sleep routines, and advocating for periods of uninterrupted rest without disruptions by the health care team.

Read more about promoting good sleep in the “Sleep and Rest” chapter.

Guidelines specific to organizations accredited by The Joint Commission that focus on problems in health care safety and ways to solve them.

An investigation by insurance agencies and other health care funders on services performed by doctors, nurses, and other health care team members to ensure money is not wasted covering things that are unnecessary for proper treatment or are inefficient.

Assessment

Subjective Assessment

During a subjective assessment of a client’s integumentary system, begin by asking about current symptoms such as itching, rashes, or wounds. If a client has a wound, it is important to determine if a client has pain associated with the wound so that pain management can be implemented. For clients with chronic wounds, it is also important to identify factors that delay wound healing, such as nutrition, decreased oxygenation, infection, stress, diabetes, obesity, medications, alcohol use, and smoking.[38] See Table 10.6a for a list of suggested interview questions to use when assessing a client with a wound.

If a client has a chronic wound or is experiencing delayed wound healing, it is important for the nurse to assess the impact of the wound on their quality of life. Reasons for this may include the frequency and regularity of dressing changes, which affect daily routine; a feeling of continued fatigue due to lack of sleep; restricted mobility; pain; odor; and the side effects of multiple medications. The loss of independence associated with functional decline can also lead to changes in overall health and well-being. These changes include altered eating habits, depression, social isolation, and a gradual reduction in activity levels.

Table 10.6a Interview Questions Related to Integumentary Disorders

| Symptoms | Questions | Follow-up Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Current Symptoms | Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole? | Please describe. |

| Wounds | Do you have any current wounds such as a surgical incision, skin tear, arterial ulcer, venous ulcer, diabetic or neuropathic ulcer, or a pressure injury?

If a wound is present:

|

Please describe.

Use the PQRSTU method to comprehensively assess pain. Read more about the PQRSTU method in the "Pain Assessment Methods" section of the "Comfort" chapter. |

| Medical History | Have you ever been diagnosed with a wound related to diabetes, heart disease, or peripheral vascular disease? | Please describe. |

| If chronic wounds or wounds with delayed healing are present: | ||

| Medications | Are you taking any medications that can affect wound healing, such as oral steroids to treat inflammation or help you breathe? | Please describe. |

| Treatments | What have you used to try to treat this wound? | What was successful? Unsuccessful? |

| Symptoms of Infection (pain, purulent drainage, etc.) | Are you experiencing any symptoms of infection related to this wound such as increased pain or yellow/green drainage? | Please describe. |

| Stress | Have you experienced any recent stressors such as surgery, hospitalization, or a change in life circumstances? | How do you cope with stress in your life? |

| Smoking | Do you smoke? | How many cigarettes do you smoke a day? How long have you smoked? Have you considered quitting smoking? |

| Quality of Life | Has this wound impacted your quality of life? | Have you had any changes in eating habits, feelings of depression or social isolation, or a reduction in your usual activity levels? |

Objective Assessment

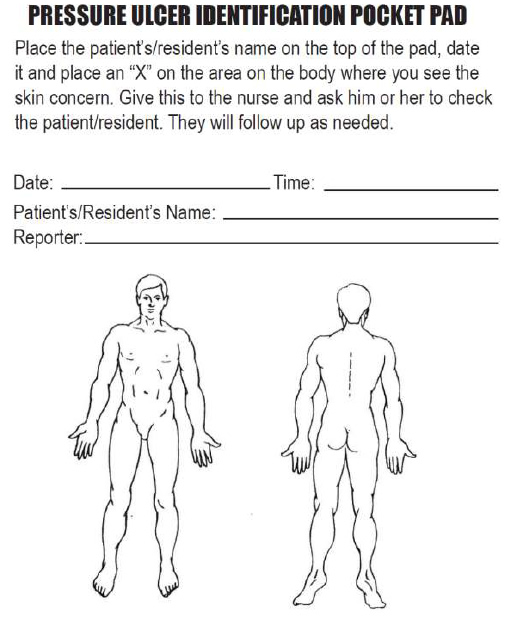

When performing an objective integumentary assessment on a client receiving inpatient care, it is important to perform a thorough exam on admission to check for existing wounds, as well as to evaluate their risk of skin breakdown using the Braden Scale. Agencies are not reimbursed for care of pressure injuries received during a client’s stay, so existing wounds on admission must be well-documented. Routine skin assessment should continue throughout a client’s stay, usually on a daily or shift-by-shift basis based on the client’s condition. If a wound is present, it is assessed during every dressing change for signs of healing. See Table 10.6b for components to include in a wound assessment. See Figure 10.22[39] for an image of a common tool used to document the location of a skin concern found during assessment.

Read more information about performing an overall integumentary assessment in the “Integumentary Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

For additional discussion regarding assessing wounds, go to the “Assessing Wounds” section of the “Wound Care” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

There are many common skin disorders that a nurse may find during assessment. Read more about common skin disorders in the “Common Integumentary Conditions” section of the “Integumentary Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Table 10.6b Wound Assessment

| Wound Assessment | |

|---|---|

| Type | Types of wounds may include abrasions, lacerations, burns, surgical incisions, pressure injuries, skin tears, arterial ulcers, or venous ulcers. It is important to understand the type of wound present to select appropriate interventions. |

| Location | The location of the wound should be documented precisely. A body diagram template is helpful to demonstrate exactly where the wound is located. |

| Size | Wound size should be measured regularly to determine if the wound is increasing or decreasing in size. Length is measured using the head-to-toe axis, and width is measured laterally. If tunneling or undermining is present, their depth should be assessed using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator and documented using the clock method. |

| Degree of Tissue Injury | Wounds are classified as partial-thickness (meaning the epidermis and dermis are affected) or full-thickness (meaning the subcutaneous and deeper layers are affected). See Figure 10.1 in the “Basic Concepts” section for an image of the layers of skin.

For pressure injuries, it is important to assess the stage of the injury (see information on staging in the “Pressure Injuries” section). |

| Color of Wound Base | Assess the base of the wound for the presence of healthy, pink/red granulation tissue. Note the unhealthy appearance of dark red granulation tissue, white or yellow slough, or brown or black necrotic tissue. |

| Drainage | The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Drainage from wounds is often described as scant, small/minimal, moderate, and large/copious amounts. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms:[40]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent:

|

| Tubes or Drains | Check for patency and if they are attached correctly. |

| Signs and Symptoms of Infection | Assess for signs and symptoms of infection, which include the following:

|

| Wound Edges and Periwound | Assess the surrounding skin for maceration or signs of infection. |

| Pain | Assess for pain in the wound or during dressing changes. If pain is present, use the PQRSTU or OLDCARTES method to obtain a comprehensive pain assessment. |

See Table 10.6c for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings on integumentary assessment.

Table 10.6c Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | Color: appropriate for ethnicity

Temperature: warm to touch Texture: smooth, soft, and supple Turgor: resilient Integrity: no wounds or lesions noted Sensory: no pain or itching noted |

Color: pale, white, red, yellow, purple, black and blue

Temperature: cool or hot to touch Texture: rough, scaly or thick; thin and easily torn; dry and cracked Turgor: tenting noted Integrity: rashes, lesions, abrasions, burns, lacerations, surgical wounds, pressure injuries noted Pain or pruritus (itching) present |

| Hair | Full distribution of hair on the head, axilla, and genitalia | Alopecia (hair loss), hirsutism (excessive hair growth over body), lice and/or nits, or lesions under hair |

| Nails | Smooth, well-shaped, and firm but flexible | Cracked, chipped, or splitting nail; excessively thick; presence of clubbing; ingrown nails |

| Skin Integrity | Skin intact with no wounds or pressure injuries. Braden Scale is 23 | A wound or pressure injury is present, or there is risk of developing a pressure injury with a Braden scale score of less than 23 |

Diagnostic and Lab Work

When a chronic wound is not healing as expected, laboratory test results can provide additional clues for the delayed healing. See Table 10.6d for a summary of lab results that offer clues to systemic issues causing delayed wound healing.

Table 10.6d Lab Values Associated with Delayed Wound Healing[46]

| Abnormal Lab Value | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low hemoglobin | Low hemoglobin indicates less oxygen is transported to the wound site. |

| Elevated white blood cells (WBC) | Increased WBC indicates infection is occurring. |

| Low platelets | Platelets have an important role in the creation of granulation tissue. |

| Low albumin | Low albumin indicates decreased protein levels. Protein is required for effective wound healing. |

| Elevated blood glucose or hemoglobin A1C | Elevated blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C levels indicate poor management of diabetes mellitus, a disease that negatively impacts wound healing. |

| Elevated serum BUN and creatinine | BUN and creatinine levels are indicators of kidney function, with elevated levels indicating worsening kidney function. Elevated BUN (blood urea nitrogen) levels impact wound healing because it can indicate increased breakdown of the body's protein stores due to deficient protein in the diet. |

| Positive wound culture | Positive wound cultures indicate an infection is present and provide additional information including the type and number of bacteria present, as well as identifying antibiotics the bacteria is susceptible to. The nurse reviews this information when administering antibiotics to ensure the prescribed therapy is effective for the type of bacteria present. |

Life Span and Cultural Considerations

Newborns and Infants

Newborn skin is thin and sensitive. It tends to be easy to scratch and bruise and is susceptible to rashes and irritation. Common rashes seen in newborns and infants include diaper rash (contact dermatitis), cradle cap (seborrheic dermatitis), newborn acne, and prickly heat.

Toddlers and Preschoolers

Because of high levels of activity and increasing mobility, this age group is more prone to accidents. Issues like lacerations, abrasions, burns, and sunburns can occur frequently. It is important to be highly aware of the potential for accidents and implement safety precautions as needed.

School-Aged Children and Adolescents

Skin rashes tend to affect skin within this age group. Impetigo, scabies, and head lice are commonly seen and may keep children home from school. Acne vulgaris typically begins during adolescence and can alter physical appearance, which can be very upsetting to this age group. Another change during adolescence is the appearance of axillary, pubic, and other body hair. Also, as these children spend more time out of doors, sunburns are more common, and care should be given to encourage sunscreen and discourage the use of tanning beds.

Adults and Older Adults

As skin ages, many changes take place. Because aging increases the loss of subcutaneous fat and collagen breakdown, skin becomes thinner and wrinkles deepen. Decreased sweat gland activity leads to drier skin and pruritus (itching). Wound healing is slowed because of reduced circulation and the inability of proteins and proper nutrients to arrive at injury sites. Hair loses pigmentation and turns gray or white. Nails become thicker and are more difficult to cut. Age or liver spots become darker and more noticeable. The number of skin growths increases and includes skin tags and keratoses.

Diagnoses

There are several NANDA-I nursing diagnoses related to clients experiencing skin alterations or those at risk of developing a skin injury. See Table 10.6e for common NANDA-I nursing diagnoses and their definitions.[47]

Table 10.6e Common NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses Related to Integumentary Disorders[48]

| Risk for Pressure Injury: “Susceptible to localized injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear.” |

| Impaired Skin Integrity: “Altered epidermis and/or dermis.” |

| Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity: “Susceptible to alteration in epidermis and/or dermis, which may compromise health.” |

| Impaired Tissue Integrity: “Damage to the mucous membrane, cornea, integumentary system, muscular fascia, muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage, joint capsule, and/or ligament.” |

| Risk for Impaired Tissue Integrity: “Susceptible to damage to the mucous membrane, cornea, integumentary system, muscular fascia, muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage, joint capsule, and/or ligament, which may compromise health.” |

A commonly used NANDA-I nursing diagnosis for clients experiencing alterations in the integumentary system is Impaired Tissue Integrity, defined as, “Damage to the mucous membrane, cornea, integumentary system, muscular fascia, muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage, joint capsule, and/or ligament.”

To verify accuracy of this diagnosis for a client, the nurse compares assessment findings with defining characteristics of that diagnosis. Defining characteristics for Impaired Tissue Integrity include the following:

- Acute pain

- Bleeding

- Destroyed tissue

- Hematoma

- Localized area hot to touch

- Redness

- Tissue damage

A sample NANDA-I diagnosis in current PES format would be: “Impaired Tissue Integrity related to insufficient knowledge about protecting tissue integrity as evidenced by redness and tissue damage.”

Outcome Identification

An example of a broad goal for a client experiencing alterations in tissue integrity is:

- The client will experience tissue healing.

A sample SMART expected outcome for a client with a wound is:

- The client’s wound will decrease in size and have increased granulation tissue within two weeks.

Planning Interventions

In addition to the interventions outlined under the “Braden Scale” section to prevent and treat pressure injury, see the following box for a list of interventions to prevent and treat impaired skin integrity. As always, consult a current, evidence-based nurse care planning resource for additional interventions when planning client care.

Selected Interventions to Prevent and Treat Impaired Skin Integrity [49],[50],[51]

- Assess and document the client’s skin status routinely. (Frequency is determined based on the client’s status.)

- Use the Braden Scale to identify clients at risk for skin breakdown. Customize interventions to prevent and treat skin breakdown according to client needs.

- If a wound is present, evaluate the healing process at every dressing change. Note and document characteristics of the wound, including size, appearance, staging (if applicable), and drainage. Notify the provider of new signs of infection or lack of progress in healing.

- Provide wound care treatments, as prescribed by the provider or wound care specialist, and monitor the client's response toward expected outcomes.

- Cleanse the wound per facility protocol or as ordered.

- Maintain non-touch or aseptic technique when performing wound dressing changes, as indicated. (Read more details about using aseptic technique and the non-touch method in the "Aseptic Technique" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Skills,2e textbook.)

- Change wound dressings as needed to keep them clean and dry and prevent bacterial reservoir.

- Monitor for signs of infection in an existing wound (as indicated by redness, warmth, edema, increased pain, reddened appearance of surrounding skin, fever, increased white blood cell count, changes in wound drainage, or sudden change in client’s level of consciousness).

- Apply lotion to dry areas to prevent cracking.

- Apply lubricant to moisten lips and oral mucosa, as needed.

- Keep skin free of excess moisture. Use moisture barrier ointments (protective skin barriers) or incontinence products in skin areas subject to increased moisture and risk of skin breakdown.

- Educate the client and/or family caregivers on caring for the wound and request return demonstrations, as appropriate.

- Administer medications, as prescribed, and monitor for expected effects.

- Consult with a wound specialist, as needed.

- Obtain specimens of wound drainage for wound culture, as indicated, and monitor results.

- Advocate for pressure-relieving devices in clients at risk for pressure injuries, such as elbow protectors, heel protectors, chair cushions, and specialized mattresses and monitor the client's response.

- Promote adequate nutrition and hydration intake, unless contraindicated.

- Use a minimum of two-person assistance and a draw sheet to pull a client up in bed to minimize shear and friction.

- Reposition the client frequently to prevent skin breakdown and to promote healing. Turn the immobilized client at least every two hours, according to a specific schedule.

- Maintain a client’s position at 30 degrees or less, as appropriate, to prevent shear.

- Keep bed linens clean, dry, and wrinkle free.

Implementation

Before implementing interventions, it is important to assess the current status of the skin and risk factors present for skin breakdown and modify interventions based on the client’s current status. For example, if a client's rash has resolved, some interventions may no longer be appropriate (such as applying topical creams). However, if a wound is showing signs of worsening or delayed healing, additional interventions may be required. As always, if the client demonstrates new signs of localized or systemic infection, the provider should be notified.

Evaluation

It is important to evaluate for healing when performing wound care. Use the following expected outcomes when evaluating wound healing:

- Resolution of periwound redness in 1 week

- 50% reduction in wound dimensions in 2 weeks

- Reduction in volume of exudate

- 25% reduction in amount of necrotic tissue/eschar in 1 week

- Decreased pain intensity during dressing changes[52]

If a client is experiencing delayed wound healing or has a chronic wound, it is helpful to advocate for a referral to a wound care nurse specialist.

Read a sample nursing care plan for a client with impaired skin integrity.