Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that we have discussed several alterations in elimination, let’s apply the nursing process to clients experiencing these conditions.

Assessment

Urinary Elimination Assessment

Assessment of the urinary system includes asking questions about voiding habits, frequency, and if there is difficult or painful urination. The bladder may be palpated above the symphysis pubis for distention. If the client has incontinence, the perineal area should be inspected for skin breakdown. If urinary retention is suspected, a post-void residual amount may be measured by using a bladder scanner or by straight urinary catheterization. For a summary of common signs and symptoms associated with alterations in urinary elimination, see the “Selected Defining Characteristics” listed in Table 16.9a under the “Diagnosis” subsection.

Bowel Elimination Assessment

Subjective assessment of the bowel system includes asking about the client’s normal bowel pattern, the date of the last bowel movement, characteristics of the stool, and if any changes have occurred recently in stool characteristics or pattern. A normal pattern is typically one bowel movement every one to three days with stools having a soft or formed consistency. Refer to Figure 16.6[1] under the “Constipation” section regarding using the Bristol Stool Chart to evaluate stool consistency.

Based on the client’s answers, additional questions can be included, such as bowel routines/toileting, the amount of fiber and fluid in the daily diet, daily activity, and the use of opioid medications. Keep in mind that clients who have recently undergone diagnostic procedures that include barium contrast can have significant hardening of the stool if the barium is not expelled within a day or two of the procedure. Clients are typically prescribed a stimulant laxative (such as Milk of Magnesia) to promote barium expulsion after these types of procedures. Additionally, clients who have recently had abdominal surgical procedures under general anesthesia are at increased risk of paralytic ileus.

For a summary of common symptoms associated with alterations in urinary elimination, see the “Selected Defining Characteristics” listed in Table 16.9a under the “Diagnosis” subsection.

The abdomen should be inspected for distension, bulging, bruising, or pulsatile masses and then auscultated for bowel sounds, noting if they are present, hyperactive, or hypoactive in all four quadrants. If bowel sounds are absent or there are other signs of possible obstruction or paralytic ileus, the provider should be notified immediately. A light palpitation of the abdomen is performed to determine if there are tender areas, abnormal masses, or a firmness in the left lower quadrant, indicating the presence of stool. If pulsatile masses, distension, rigidity, or other indication of suspected abdominal problems is noted on inspection, the abdomen should not be deeply palpated due to the risk of injury or complications with palpation.[2]

During inpatient care, the client is often requested to call the nurse when a bowel movement has occurred so the stool characteristics can be assessed. Document the amount (small, medium, or large), consistency (soft, formed, or hard) and color (brown or other color). Alterations in these characteristics can be caused by several conditions, such as infection, parasites, inflammatory conditions of the intestines or gallbladder, or liver conditions.

Some clients have surgical diversions for diseases such as diverticulitis or cancer. Ostomies are surgical openings in the abdomen for the expulsion of stool into a bag-like appliance. An ileostomy is an opening created at the juncture of the small and large intestines, so the stool has a liquid consistency. A colostomy is placed farther along the large intestines, where more water has been absorbed, so the stool is more formed.

Read about expected and unexpected findings during an abdominal assessment in the “Abdominal Assessment” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Read about caring for clients with ostomies in the “Facilitation of Elimination” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Urinary Diagnostic Tests

There are several commonly ordered diagnostic tests for urinary conditions, such as a urine dip, urinalysis, urine culture, cystoscopy, and urodynamic flow studies.

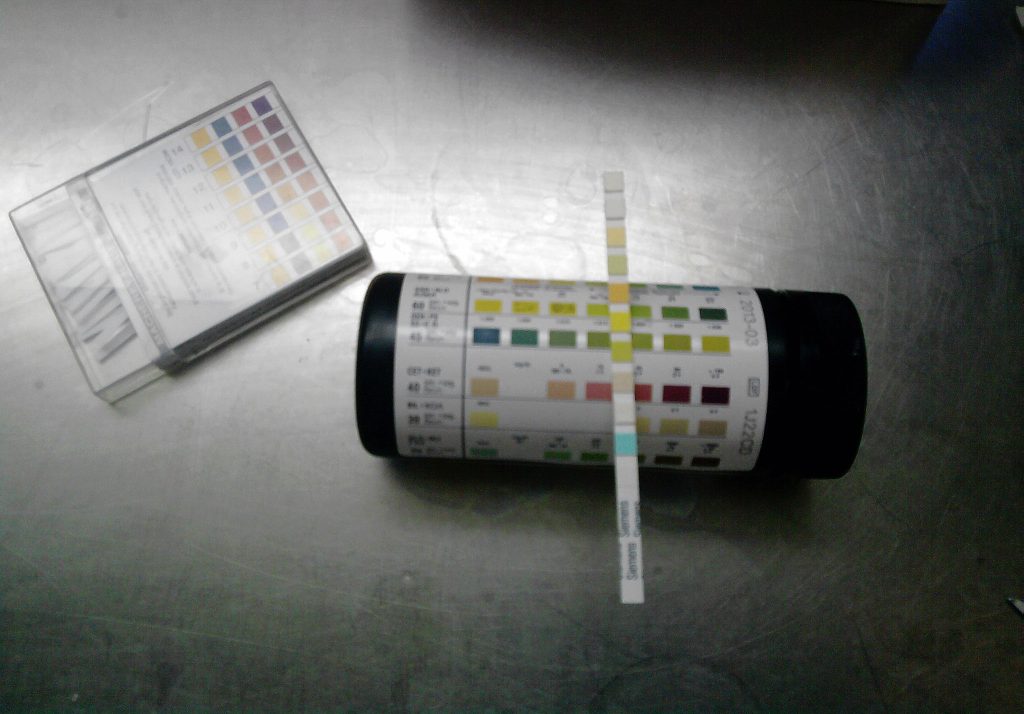

Urine Dip

A urine dip test refers to a treated chemical strip (dipstick) being placed in a urine sample. Patches on the dipstick will change color to indicate the presence of substances such as white blood cells, protein, or glucose. See Figure 16.7[3] for an image of a urine dipstick test. Urine is collected for a urine dip test in a clean container. Using the “clean catch” technique, the skin surrounding the urethra should be cleaned with a special towelette before the urine is collected. Catching the urine “midstream” is the goal, so request the client to start urinating, stop, and then urinate into the container.

Urinalysis

A urinalysis includes a physical, chemical, and microscopic examination of urine by a lab technician. It requires collection of a “clean catch” urine sample in a sterile container that is analyzed by a lab technician under a microscope.[4] See Table 16.9a for a selected urinalysis findings and their clinical significance.

Table 16.9a Selected Urinalysis Findings and Their Clinical Significance[5]

| Component | Normal Findings | Abnormal Findings & Their Clinical Significance |

| Color | Yellow (light/pale to dark) | Amber: Bile pigments

Tea-colored: Bile pigments, medication side effects Dark yellow: Concentrated urine Green/blue: Side effects of medication Orange: Bile pigments or side effects of medications or food Pink/Red: Blood in urine, menstrual contamination, uric acid crystals, side effects of medication or food |

| Appearance | Clear, translucent | Cloudy: Bacteria, precipitation of cells, pus, or contamination |

| Odor | None or typical urine odor | Fruity/sweet: Diabetic ketoacidosis

Fecal smell: Gastrointestinal/bladder fistula or fecal contamination Pungent: Urinary tract infection |

| Urine pH | 4.5-8 | >8: Old specimens, vegetarian diet, vomiting

<4.5: Cranberry juice, dehydration, diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, diarrhea, emphysema, high protein diet, medication side effects |

| Red Blood Cells (RBCs) | 0-5 RBCs per mL | Greater than 5 RBCs/ml (hematuria): Renal stones, pyelonephritis, tumors, trauma, contamination with menstrual blood, contamination post masturbation |

| White Blood Cells (WBCs) | 0-5 WBC s per mL | Greater than 5 WBCs/ml: Urinary tract infection, inflammation |

| Nitrites | Negative | Positive: Urinary tract infection (*However, false-positive and false-negative results can occur.) |

| Leukocyte esterase | Negative | Positive: Inflammation of urinary tract, tuberculosis, bladder tumors, kidney stones, or fever (*However, false-positive and false-negative results can occur.) |

| Protein | <150 mg/day or <10 mg/dL | >150 mg/day or > 10mg/dL: Early renal disease, pyelonephritis, congestive heart failure, physiological conditions such as strenuous exercise, fever, dehydration; false positive/negative results based on urine pH and concentration |

| Glucose | Negative | Positive: Diabetes, Cushing syndrome, pregnancy; false-positive with ketone presence |

| Ketones | Negative | Positive: Diabetic ketoacidosis, pregnancy, keto diet, starvation, fever |

| Bilirubin | Negative | Positive: Liver dysfunction, bile duct obstruction, hepatitis, cirrhosis |

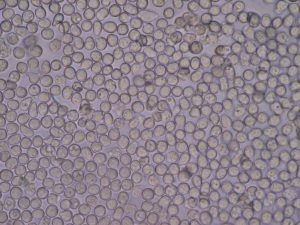

See Figure 16.8[6] for an image of white blood cells, referred to as pyuria, as seen on a urinalysis under a microscope. A urinalysis looks for evidence of infection, including elevated numbers of bacteria and white blood cells. A positive leukocyte esterase test or the presence of nitrite also supports the diagnosis of a UTI.[7]

Urine Culture

A urine culture identifies the specific microbe causing a urinary tract infection. If this is the client’s first, uncomplicated UTI of the lower urinary tract, the provider often assumes it is caused by the most common microbe, E. coli, and treats it with antibiotics without performing a culture. However, cultures are typically performed for clients with recurring UTIs or hospitalized clients at risk for hospital-associated infections.[8]

When interpreting urine culture results, the presence of a single type of bacteria growing at high colony counts is typically considered a positive urine culture. For clean catch samples that have been properly collected, cultures with greater than 100,000 colony forming units (CFU)/milliliter of one type of bacteria usually indicate infection.[9]

If a culture is positive, susceptibility testing is performed to guide treatment. Although a variety of bacteria can cause UTIs, most are due to Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria that are common in the digestive tract and routinely found in stool. Other bacteria that commonly cause UTIs include Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Staphylococcus, and Acinetobacter. Susceptibility testing determines which antibiotics will inhibit the growth of the specific bacteria causing the infection. It is important for nurses to review culture results to verify the antibiotic therapy being administered has been found to be effective against the type of bacteria discovered in the culture. If there is any concern about the susceptibility results and current antibiotic therapy, the health care provider should be notified.

A culture that is reported as “no growth in 24 or 48 hours” usually indicates that there is no infection. If a culture shows growth of several different types of bacteria, then it is likely due to contamination of the urine sample during collection. This is especially true in voided urine samples if the organisms present include Lactobacillus and/or other common nonpathogenic vaginal bacteria in women. The provider may request a repeat culture on a sample that is more carefully collected.[10]

Cystoscopy

A cystoscopy is a procedure completed by a health care provider with a cystoscope, a small, thin tube with a camera on the end that is inserted into the urethra and into the bladder. See Figure 16.9[11] for an illustration of cystoscopy. Fluid is inserted to expand the bladder so the bladder walls can be visualized. Biopsy samples can be taken from abnormal tissue through the tube and then sent to a medical lab for analysis. The client will feel the need to urinate when the bladder is full, but the bladder must stay full until the procedure is completed. A slight pinch may be felt if a biopsy sample is obtained. After the procedure, the client should be encouraged to drink four to six glasses of water per day, as appropriate for their medical status. A small amount of blood may be present in the urine after the procedure, but if the bleeding continues after urinating three times, or if other signs of infection are present, the provider should be notified.[12]

Urodynamic Flow Test

Urodynamic testing is any procedure that looks at how well the bladder, sphincters, and urethra are storing and releasing urine. Most urodynamic tests focus on the bladder’s ability to hold urine and empty steadily and completely. Urodynamic tests can also show whether the bladder is having involuntary contractions that cause urine leakage.[13]

Bowel Diagnostic Tests

There are several common diagnostic tests related to bowel elimination, including stool-based tests, a colonoscopy, a barium enema, and an abdominal CT scan.

Stool-Based Tests

Stool samples can be tested for bacteria, viruses, parasites, cancer, or for occult blood (i.e., hidden blood). Follow specific instructions from the lab for collecting the sample.

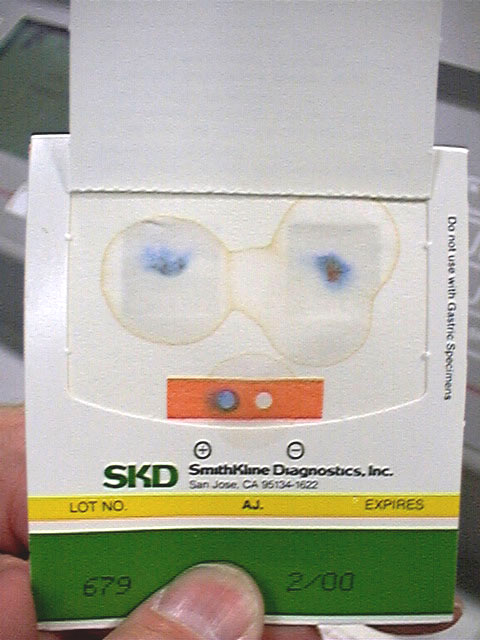

The Guaiac-Based Fecal Occult Blood Test finds hidden blood in the stool. As a screening test for colon cancer, it is performed annually. Before the test, the client should avoid many foods, such as red meat, melons, beets, and grapefruit for three days. They should not take aspirin or NSAIDs for seven days prior to the test. Stool samples from three separate bowel movements are smeared onto small paper cards and then returned to the medical lab for testing. If the test is positive (i.e., hidden blood is found), a follow-up colonoscopy is scheduled.[14] See Figure 16.10[15] for an image of a typical card used to collect the stool smear for the test after a special solution has been applied. The blue color indicates a positive result for occult blood.

The Stool DNA Test (also called Cologuard) looks for certain abnormal sections of DNA from cancer or polyp cells and also checks for occult blood. Specific collection kits, including a sample container, liquid preservative, and specific instructions are provided.[16]

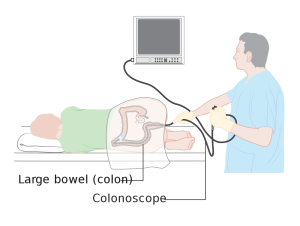

Colonoscopy

During a colonoscopy, an instrument called a colonoscope is used. The colonoscope has a tiny camera attached to a long, thin tube that is inserted into the anus to check the entire colon and rectum. See Figure 16.11[17] for an illustration of a colonoscopy. This procedure is used to screen clients for colon cancer. Screening is recommended to start at age 50 (or 45 for high-risk populations, including African Americans), and thereafter once every ten years or as prescribed by the provider. It is also used to evaluate the colon for inflamed tissue and abnormal growths or lesions. Before the procedure, the client must complete a bowel prep that typically consists of a clear liquid diet and laxatives the day before the procedure to clean out the intestine so that everything can be seen clearly. Each provider typically has their own specific set of bowel prep instructions. Medications such as aspirin or anticoagulants may be ordered to be withheld for several days before the test. Clients are generally NPO after a specific time the night before the test. During the procedure, the client receives sedative medication to stay relaxed. If a polyp is found, it can be removed during the procedure and sent for biopsy. Because air is inserted into the colon during procedure, the client may feel bloated or have abdominal cramps and should be encouraged to freely pass the gas. Because this is typically an outpatient procedure, the client is unable to drive after the test and requires transportation. Potential complications of the procedure are rare but include bleeding and perforation of the colon. The client should receive written instructions for when to contact the health care provider or emergency services if complications occur.[18],[19]

Barium Enema

A barium enema is a special X-ray of the large intestine, including the colon and rectum, that is performed before and after instillation of barium via an enema. This test may also be referred to a “lower GI series.” It is an older diagnostic test that has been mostly replaced by the colonoscopy test. Prior to the procedure, the client completes a bowel preparation regimen to cleanse the colon, which typically includes a clear liquid diet for one to three days, followed by the administration of laxative medication and/or an enema. During the procedure, an X-ray is taken, and then an enema containing barium is administered. Additional X-rays are taken as the client changes position to get different views of the colon. See Figure 16.12[20] for an image of barium enema results. After the procedure, it is normal for the client to have white stools for a few days. The client should be encouraged to drink extra fluids, as appropriate, and a laxative may be prescribed to prevent hard stools that can cause constipation.[21]

Abdominal CT Scan

An abdominal CT scan is an imaging method that uses a series of X-rays to create cross-sectional pictures of the abdomen. Because of the series of X-rays, clients are exposed to more radiation than when receiving a traditional X-ray. They will lie on a narrow table that slides into the CT scanner where the machine’s X-ray beam rotates around them. A computer creates separate images, called slices, that can be viewed on a monitor or printed on film. Three-dimensional models of the area can be made by stacking the slices together.[22] See Figure 16.13[23] for an image of a CT scan.

A special dye, called contrast, is administered to clients before some tests so that certain areas show up better on the X-rays. If contrast is used, the client may be required to be NPO for four to six hours before the test. Contrast can be administered orally, rectally, or intravenously.

Oral contrast has a chalky taste and will pass out of your body through the stools. Clients receiving IV contrast may feel a slight burning sensation, metallic taste in the mouth, or warm flushing of the body that resolves in a few seconds.

Before sending the client for a procedure using contrast, check for previous allergies to iodine or other contrast dyes. Some clients may be prescribed diphenhydramine or corticosteroids before receiving the contrast if they have had a previous allergic reaction. Verify their kidney functioning status by checking BUN, creatinine, and EGFR values because IV contrast can worsen kidney function. If kidney function labs are abnormal, the nurse should notify the provider prior to the administration of IV contrast. If the client is currently taking the antidiabetic medication metformin, there may be restrictions placed on the administration of metformin before or after the procedure. Jewelry should be removed before the procedure.[24]

After the procedure, encourage clients who have received contrast to increase their fluid intake to help eliminate it from their body, as appropriate. If they received barium, their stools will be light in color, and post-procedural laxatives are typically prescribed to prevent the stool from hardening, which can cause an impaction or obstruction.

Diagnosis

There are several nursing diagnoses related to alterations in elimination. Refer to a nursing care planning resource for current NANDA-I nursing diagnoses and evidence-based interventions. See Table 16.9b for common NANDA-I diagnoses related to elimination.

Table 16.9b Common NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses Related to Alterations in Elimination

| NANDA-I Diagnosis | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Constipation | Decrease in normal frequency of defecation accompanied by difficult or incomplete passage of stool and/or passage of excessively hard, dry stool |

|

| Diarrhea | Passage of loose, unformed stools |

|

| Bowel Incontinence | Involuntary passage of stool |

|

| Stress Urinary Incontinence | Sudden leakage of urine with activities that increase intraabdominal pressure |

|

| Urge Urinary Incontinence | Involuntary passage of urine occurring soon after a strong sensation or urgency to void |

|

| Urinary Retention | Inability to empty bladder completely |

|

Sample PES Statements

Sample PES statements for the nursing diagnoses are as follows:

- Constipation related to insufficient fluid and fiber intake as evidenced by decreased stool frequency, hypoactive bowel sounds, and straining with defecation.

- Diarrhea related to gastrointestinal irritation as evidenced by cramping, hyperactive bowel sounds, and greater than three liquid stools in 24 hours.

- Bowel Incontinence related to generalized decline in muscle tone as evidenced by an involuntary passage of stool.

- Stress Incontinence related to weak pelvic muscle floor muscles as evidenced by leakage of a small amount of urine when laughing and jumping.

- Urinary Urge Incontinence related to ineffective toileting habits as evidenced by the inability to reach the toilet in time to avoid urine loss and frequently wet underclothes.

- Urinary Retention related to blockage in the urinary tract as evidenced by dribbling of urine in small amounts with frequent voiding and a reported sensation of bladder fullness.

Outcome Identification

See Table 16.9c for sample goals and outcome criteria associated with nursing diagnoses related to elimination alterations.

Table 16.9c Sample Goals and Outcome Criteria for Alterations in Elimination

| Nursing Diagnosis | Overall Goal | SMART Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Constipation | The client will have a bowel movement every 1-3 days with soft, formed stool and ease of stool passage. | The client will have a bowel movement with soft, formed stool in the next 24 hours. |

| Diarrhea | The client will have a regular bowel elimination pattern with soft, formed stool. | The client will report relief from cramping and fewer episodes of diarrhea in the next eight hours. |

| Stress Incontinence | The client will have urinary continence as evidenced by no urine leakage with intra-abdominal pressure and dry underclothes and bedding. | The client will report fewer episodes of stress incontinence in their bladder log over the next month. |

| Urge Incontinence | The client will have urinary continence as evidenced by adequate time to reach the toilet and dry underclothes and bedding. | The client will report fewer incontinence episodes over the next month. |

| Urinary Retention | The client will experience improved urinary elimination as evidenced by complete emptying of the bladder and absence of urinary leakage. | The client will report a feeling of complete emptying of the bladder by next week. |

Planning Interventions

Plan interventions customized to each client’s alteration, cause of the condition, and related SMART outcomes. See Table 16.9d for a summary of interventions for selected bladder and bowel alterations discussed in this chapter.

16.9d Summary of Interventions For Selected Bladder and Bowel Alterations

| Alteration | Interventions |

| Urinary Tract Infection | Administer antibiotics as prescribed

Encourage increased fluid intake Provide client education regarding UTI prevention, including:

|

| Urinary Incontinence | Engage with client using therapeutic communication

Provide client education regarding bladder control training, including:

|

| Urinary Retention | Monitor post-void residual

Perform bladder scanning to determine presence of urine in bladder Perform urinary catheterization to empty bladder Administer medications as prescribed to relax prostate Monitor for signs of UTI due to retained urine Provide client education regarding bladder control training as appropriate |

| Constipation | Implement bowel regimen as ordered, such as oral stool softeners, mild stimulant laxatives, progressing to stronger laxatives, rectal suppositories, or enemas

Provide client education and encouragement regarding the importance of:

|

| Fecal Impaction | Administer mineral oil enemas

Digitally remove impacted stool using a lubricated, gloved finger |

| Intestinal Obstruction or Paralytic Ileus | Maintain strict NPO status

Monitor for return of bowel sounds or change in bowel sounds and report to provider as appropriate Assess abdomen for distention, rigidity, pain, or worsening of symptoms and report to provider as appropriate Insert and/or maintain nasogastric tube as ordered |

| Diarrhea | Encourage oral fluid intake

Maintain IV hydration as ordered Monitor for electrolyte disturbances Monitor for skin breakdown and apply skin protectants as appropriate Administer medications to slow intestinal motility as ordered and as appropriate Insert and/or maintain rectal tube as ordered |

| Bowel Incontinence | Engage with client using therapeutic communication

Encourage client to maintain a food diary to determine if certain food cause incontinence problems Encourage increased intake of fiber to bulk up stool Assist client to toilet after meals and when client feels urge to defecate Ensure privacy during toileting Encourage the use of incontinence products as appropriate Provide client education regarding bowel retraining, including the following topics:

|

Implementing Interventions

Assess a hospitalized client’s bowel pattern and date of last bowel movement daily. Implement a bowel management plan as needed to achieve the goal of a bowel movement every one to three days to avoid constipation and impaction. Before administering laxatives and stool softeners, always assess the clientt’s recent stool characteristics and withhold medication if loose stools or diarrhea are occurring. In the same manner, when administering medications for a client with diarrhea, assess recent stool consistency and bowel pattern and withhold medication if the diarrhea is resolved or constipation is developing.

For many clients, alterations in elimination require health teaching on how to manage these conditions at home. Keep in mind that health teaching is an independent nursing intervention, so a provider order is not necessary to provide this important information.

Evaluation

Nurses evaluate the effectiveness of interventions based on the SMART outcomes established for each client and their circumstances. They determine if outcome criteria were met or if reassessment and/or revised interventions are required.

- “Bristol_stool_chart.svg” by Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Mehta, M. (2010). Assessing the abdomen. Nursing Critical Care, 5(1), 47-48. https://doig.org/10.1097/01.CCN.0000365703.35731.b7 ↵

- “Chemstrip2.jpg” by J3D3 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Jun 9]. Urinalysis; [reviewed 2016, May 5; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/urinalysis.html ↵

- Queremel, M. & Jialal, I. (2023, Updated May 1) Urinalysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557685/ ↵

- “Pyuria2.JPG” by Bobjgalindo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- LabTestsOnline.org. (2020, March 21). Urinary tract infection. https://labtestsonline.org/conditions/urinary-tract-infection ↵

- LabTestsOnline.org. (2020, August 12). Urine culture. https://labtestsonline.org/tests/urine-culture ↵

- LabTestsOnline.org. (2020, August 12). Urine culture. https://labtestsonline.org/tests/urine-culture ↵

- LabTestsOnline.org. (2020, August 12). Urine culture. https://labtestsonline.org/tests/urine-culture ↵

- “Diagram_showing_a_cystoscopy_for_a_man_and_a_woman_CRUK_064.svg” by Cancer Research UK is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2021. Cystoscopy; [updated 2021, Feb 8; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003903.htm ↵

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2014, February). Urodynamic testing. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diagnostic-tests/urodynamic-testing ↵

- American Cancer Society. (2020, June 29). Colorectal cancer screening tests. https://www.cancer.org/content/cancer/en/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/screening-tests-used.html ↵

- “Guaiac_test.jpg” by unknown author is in the Public Domain ↵

- American Cancer Society. (2020, June 29). Colorectal cancer screening tests. https://www.cancer.org/content/cancer/en/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/screening-tests-used.html ↵

- “Diagram_showing_a_colonoscopy_CRUK_060.svg” by Cancer Research UK is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Feb 3]. Colonoscopy; [reviewed 2018, May 1; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/colonoscopy.html ↵

- American Cancer Society. (2019, January 14). Colonoscopy. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/tests/endoscopy/colonoscopy.html ↵

- “Human_intestinal_tract,_as_imaged_via_double-contrast_barium_enema.jpg” by Glitzy queen00 at English Wikipedia is in the Public Domain ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2021. Barium enima; [updated 2021, Feb 8; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003817.htm ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2021. Abdominal CT scan; [updated 2021, Feb 8; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003789.htm ↵

- “UW_Medical_Center_PET-CT-Scan.jpg” by Clare McLean for UW Medicine is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2021. Abdominal CT scan; [updated 2021, Feb 8; cited 2021, Feb 16]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003789.htm ↵

As with electrolytes, correct balance of acids and bases in the body is essential to proper body functioning. Even a slight variance outside of normal can be life-threatening, so it is important to understand normal acid-base values, as well their causes and how to correct them. The kidneys and lungs work together to correct slight imbalances as they occur. As a result, the kidneys compensate for shortcomings of the lungs, and the lungs compensate for shortcomings of the kidneys.

Arterial Blood Gases

Arterial blood gases (ABG) are measured by collecting blood from an artery, rather than a vein, and are most commonly collected via the radial artery. ABGs measure the pH level of the blood, the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2), the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2), the bicarbonate level (HCO3), and the oxygen saturation level (SaO2).

![]() Prior to collecting blood gases, it is important to ensure the client has appropriate arterial blood flow to the hand. This is done by performing the Allen test. When performing the Allen test, pressure is held on both the radial and ulnar artery below the wrist. Pressure is released from the ulnar artery to check if blood flow is adequate. If arterial blood flow is adequate, warmth and color should return to the hand.

Prior to collecting blood gases, it is important to ensure the client has appropriate arterial blood flow to the hand. This is done by performing the Allen test. When performing the Allen test, pressure is held on both the radial and ulnar artery below the wrist. Pressure is released from the ulnar artery to check if blood flow is adequate. If arterial blood flow is adequate, warmth and color should return to the hand.

pH

pH is a scale from 0-14 used to determine the acidity or alkalinity of a substance. A neutral pH is 7, which is the same pH as water. Normally, the blood has a pH between 7.35 and 7.45. A blood pH of less than 7.35 is considered acidic, and a blood pH of more than 7.45 is considered alkaline.

The pH of blood is a measure of hydrogen ion concentration. A low pH, less than 7.35, occurs in acidosis when the blood has a high hydrogen ion concentration. A high pH, greater than 7.45, occurs in alkalosis when the blood has a low hydrogen ion concentration. Hydrogen ions are by-products of the metabolism of substances such as proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. These by-products create extra hydrogen ions (H+) in the blood that need to be balanced and kept within normal range as described earlier.

The body has several mechanisms for maintaining blood pH. The lungs are essential for maintaining pH, and the kidneys also play a role. For example, when the pH is too low (i.e., during acidosis), the respiratory rate quickly increases to eliminate acid in the form of carbon dioxide (CO2). The kidneys excrete additional hydrogen ions (acid) in the urine and retain bicarbonate (base). Conversely, when the pH is too high (i.e., during alkalosis), the respiratory rate decreases to retain acid in the form of CO2. The kidneys excrete bicarbonate (base) in the urine and retain hydrogen ions (acid).

PaCO2

PaCO2 is the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide in the blood. The normal PaCO2 level is 35-45 mmHg. CO2 forms an acid in the blood that is regulated by the lungs by changing the rate or depth of respirations.

As the respiratory rate increases or becomes deeper, additional CO2 is removed, causing decreased acid (H+) levels in the blood and increased pH (i.e., the blood becomes more alkaline). As the respiratory rate decreases or becomes shallower, less CO2 is removed, causing increased acid (H+) levels in the blood and decreased pH (i.e., the blood becomes more acidic).

Generally, the lungs work quickly to regulate the PaCO2 levels and cause a quick change in the pH. Therefore, an acid-base problem caused by hypoventilation can be quickly corrected by increasing ventilation, and a problem caused by hyperventilation can be quickly corrected by decreasing ventilation. For example, if an anxious client is hyperventilating, they may be asked to breathe into a paper bag to rebreathe some of the CO2 they are blowing off. Conversely, a postoperative client who is experiencing hypoventilation due to the sedative effects of receiving morphine is asked to cough and deep breathe to blow off more CO2.

HCO3

HCO3 is the bicarbonate level of the blood and the normal range is 22-26. HCO3 is a base managed by the kidneys and helps to make the blood more alkaline. The kidneys take longer than the lungs to adjust the acidity or alkalinity of the blood, and the response is not visible upon assessment. As the kidneys sense an alteration in pH, they begin to retain or excrete HCO3, depending on what is needed. If the pH becomes acidic, the kidneys retain HCO3 to increase the amount of bases present in the blood to increase the pH (i.e., the blood becomes alkaline). Conversely, if the pH becomes alkalotic, the kidneys excrete more HCO3, causing the pH to decrease (i.e., the blood becomes more acidic).

PaO2

PaO2 is the partial pressure of arterial oxygen in the blood. It more accurately measures a client’s oxygenation status than SaO2 (the measurement of hemoglobin saturation with oxygen). Therefore, ABG results are also used to manage clients in respiratory distress.

See Table 15.5a for a review of ABG components, normal values, and key critical values. A critical ABG value means there is a greater risk of serious complications and even death if not corrected rapidly. For example, a pH of 7.10, a shift of only 0.25 below normal, is often fatal because this level of acidosis can cause cardiac or respiratory arrest or significant hyperkalemia.[1] As you can see, failure to recognize ABG abnormalities can have serious consequences for your clients.

Table 15.5a ABG Components, Descriptions, Adult Normal Values, and Critical Values[2]

| ABG Component | Description | Adult Normal Value | Critical Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH |

|

7.35-7.45 | Less than 7.25

Greater than 7.60 |

| PaO2 |

|

80-100 mmHg | Less than 60 mmHg |

| PaCO2 |

|

35-45 mmHg | Less than 25 mmHg

Greater than 60 mmHg |

| HCO3 |

|

22-26 mEq/L | Less than 10 mEq/L

Greater than 40 mEq/L |

| SaO2 |

|

95-100% | Less than 88% |

Video Review of Acid-Base Balance[3]

Interpreting Arterial Blood Gases

After the ABG results are received, it is important to understand how to interpret them. A variety of respiratory, metabolic, electrolyte, or circulatory problems can cause acid-base imbalances. Correct interpretation helps the nurse and other health care providers determine the appropriate treatment and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

Arterial blood gasses can be interpreted as one of four conditions: respiratory acidosis, respiratory alkalosis, metabolic acidosis, or metabolic alkalosis. Once this interpretation is made, conditions can further be classified as compensated, partially compensated, or uncompensated. A simple way to remember how to interpret ABGs is by using the ROME method of interpretation, which stands for Respiratory Opposite, Metabolic Equal. This means that the respiratory component (PaCO2) moves in the opposite direction of the pH if the respiratory system is causing the imbalance. If the metabolic system is causing the imbalance, the metabolic component (HCO3) moves in the same direction as the pH. Some nurses find the Tic-Tac-Toe method of interpretation helpful. If you would like to learn more about this method, watch the video below.

Review of Tic-Tac-Toe Method of ABG Interpretation[4]

Respiratory Acidosis

Respiratory acidosis develops when carbon dioxide (CO2) builds up in the body (referred to as hypercapnia), causing the blood to become increasingly acidic. Respiratory acidosis is identified when reviewing ABGs and the pH level is below 7.35 and the PaCO2 level is above 45, indicating the cause of the acidosis is respiratory. Note that in respiratory acidosis, as the PaCO2 level increases, the pH level decreases. Respiratory acidosis is typically caused by a medical condition that decreases the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide at the alveolar level, such as an acute asthma exacerbation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or an acute heart failure exacerbation causing pulmonary edema. It can also be caused by decreased ventilation from anesthesia, alcohol, or administration of medications such as opioids and sedatives.

Chronic respiratory diseases, such as COPD, often cause chronic respiratory acidosis that is fully compensated by the kidneys retaining HCO3. Because the carbon dioxide levels build up over time, the body adapts to elevated PaCO2 levels, so they are better tolerated. However, in acute respiratory acidosis, the body has not had time to adapt to elevated carbon dioxide levels, causing mental status changes associated with hypercapnia. Acute respiratory acidosis is caused by acute respiratory conditions, such as an asthma attack or heart failure exacerbation with pulmonary edema when the lungs suddenly are not able to ventilate adequately. As breathing slows and respirations become shallow, less CO2 is excreted by the lungs and PaCO2 levels quickly rise.

Signs of symptoms of hypercapnia vary depending upon the level and rate of CO2 accumulation in arterial blood:

- Clients with mild to moderate hypercapnia may be anxious and/or complain of mild dyspnea, daytime sluggishness, headaches, or hypersomnolence.

- Clients with higher levels of CO2 or rapidly developing hypercapnia develop delirium, paranoia, depression, confusion, or decreased level of consciousness that can progress to seizures and coma as levels continue to rise.

Individuals with normal lung function typically exhibit a depressed level of consciousness when the PaCO2 is greater than 75 to 80 mmHg, whereas clients with chronic hypercapnia may not develop symptoms until the PaCO2 rises above 90 to 100 mmHg.[5]

When a client demonstrates signs of potential hypercapnia, the nurse should assess airway, breathing, and circulation. It is important to note that SaO2 levels may be normal with hypercapnia, and as such should not be the determining factor in further assessing acid-base issues. Urgent assistance should be sought, especially if the client is in respiratory distress. The provider will order an ABG and prescribe treatments based on assessment findings and potential causes. Treatment for respiratory acidosis typically involves improving ventilation and respiration by removing airway restrictions, reversing oversedation, administering nebulizer treatments, or increasing the rate and depth of respiration by using a BiPAP or CPAP devices. BiPAP and CPAP devices provide noninvasive positive pressure ventilation to increase the depth of respirations, remove carbon dioxide, and oxygenate the client. If these noninvasive interventions are not successful, the client will need to be intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation.[6],[7]

Read more details about oxygenation equipment in “Oxygen Therapy” in Open RN Nursing Skills, 2e.

Respiratory Alkalosis

Respiratory alkalosis develops when the body removes too much carbon dioxide through respiration, resulting in increased pH and an alkalotic state. When reviewing ABGs, respiratory alkalosis is identified when pH levels are above 7.45 and the PaCO2 level is below 35. With respiratory alkalosis, notice that as the PaCO2 level decreases, the pH level increases.

Respiratory alkalosis is caused by hyperventilation that can occur due to anxiety, panic attacks, pain, fear, head injuries, or mechanical ventilation. Overdoses of salicylates and other toxins can also cause respiratory alkalosis initially and then often progress to metabolic acidosis in later stages. Acute asthma exacerbations, pulmonary embolisms, or other respiratory disorders can initially cause respiratory alkalosis as the lungs breathe faster in an attempt to increase oxygenation, which decreases the PaCO2. After a while, however, these hypoxic disorders cause respiratory acidosis as respiratory muscles tire, breathing slows, and CO2 builds up in the blood.

Clients experiencing respiratory alkalosis often report feelings of shortness of breath, dizziness or light-headedness, chest pain or tightness, paresthesias, and palpitations as a result of decreased carbon dioxide levels.[8] Respiratory alkalosis is not fatal, but it is important to recognize that underlying conditions such as an asthma exacerbation or pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening, so treatment of these underlying conditions is essential. As the pH level increases, the kidneys will attempt to compensate for the shortage of H+ ions by reabsorbing HCO3 before it can be excreted in the urine. This is a slow process, so additional treatment may be necessary.

Treatment of respiratory alkalosis involves treating the underlying cause of the hyperventilation. Acute management of clients who are hyperventilating should focus on client reassurance, an explanation of the symptoms the client is experiencing, removal of any stressors, and initiation of breathing retraining. Breathing retraining attempts to focus the client on abdominal (diaphragmatic) breathing. Read more about breathing retraining in the following box.

Breathing Retraining

While sitting or lying supine, the client should place one hand on their abdomen and the other on the chest, and then be asked to observe which hand moves with greater excursion. In hyperventilating clients, this will almost always be the hand on the chest. Ask the client to adjust their breathing so that the hand on the abdomen moves with greater excursion and the hand on the chest barely moves at all. Assure the client that this is hard to learn and will take some practice to fully master. Ask the client to breathe in slowly over four seconds, pause for a few seconds, and then breathe out over a period of eight seconds. After 5 to 10 such breathing cycles, the client should begin to feel a sense of calmness with a reduction in anxiety and an improvement in hyperventilation. Symptoms should ideally resolve with continuation of this breathing exercise.

If the breathing retraining technique is not successful in resolving a hyperventilation episode and severe symptoms persist, the client may be prescribed a small dose of a short-acting benzodiazepine (e.g., lorazepam 0.5 to 1 mg orally or 0.5 to 1 mg intravenously). Current research indicates that instructing clients who are hyperventilating to rebreathe carbon dioxide (CO2) by breathing into a paper bag can cause significant hypoxemia with significant complications, so this intervention is no longer recommended. If rebreathing is used, oxygen saturation levels should be continuously monitored.[9]

Metabolic Acidosis

Metabolic acidosis occurs when there is an accumulation of acids (hydrogen ions) and not enough bases (HCO3) in the body. Under normal conditions, the kidneys work to excrete acids through urine and neutralize excess acids by increasing bicarbonate (HCO3) reabsorption from the urine to maintain a normal pH. When the kidneys are not able to perform this buffering function to the level required to excrete and neutralize the excess acid, metabolic acidosis results.

Metabolic acidosis is characterized by a pH level below 7.35 and an HCO3 level below 22 when reviewing ABGs. It is important to notice that both the pH and HCO3 decrease with metabolic acidosis (i.e., the pH and HCO3 move in the same downward direction). A common cause of metabolic acidosis is diabetic ketoacidosis, where acids called ketones build up in the blood when blood sugar is extremely elevated. Another common cause of metabolic acidosis in hospitalized clients is lactic acidosis, which can be caused by impaired tissue oxygenation. Metabolic acidosis can also be caused by increased loss of bicarbonate due to severe diarrhea or from renal disease that causes decreased acid elimination. Additionally, toxins such as salicylate excess can cause metabolic acidosis.[10]

Nurses may first suspect that a client has metabolic acidosis due to rapid breathing that occurs as the lungs try to remove excess CO2 in an attempt to resolve the acidosis. Other symptoms of metabolic acidosis include confusion, decreased level of consciousness, hypotension, and electrolyte disturbances that can progress to circulatory collapse and death if not treated promptly. It is important to quickly notify the provider of suspected metabolic acidosis so that an ABG can be drawn, and treatment prescribed (based on the cause of the metabolic acidosis) to allow acid levels to improve. Treatment includes IV fluids to improve hydration status, glucose management, and circulatory support. When pH drops below 7.1, IV sodium bicarbonate is often prescribed to help neutralize the acids in the blood.[11],[12]

Metabolic Alkalosis

Metabolic alkalosis occurs when there is too much bicarbonate (HCO3) in the body or an excessive loss of acid (H+ ions). Metabolic alkalosis is defined by a pH above 7.45 and an HCO3 level above 26 on ABG results. Note that both pH and HCO3 are elevated in metabolic alkalosis.

Metabolic alkalosis can be caused by gastrointestinal loss of hydrogen ions, excessive urine loss, excessive levels of bicarbonate, or a shift of hydrogen ions from the bloodstream into cells.

Prolonged vomiting or nasogastric suctioning can also cause metabolic alkalosis. Gastric secretions have high levels of hydrogen ions (H+), so as acid is lost, the pH level of the bloodstream increases.

Excessive urinary loss (due to diuretics or excessive mineralocorticoids) can cause metabolic alkalosis due to loss of hydrogen ions in the urine. Intravenous administration of sodium bicarbonate can also cause metabolic alkalosis due to increased levels of bases introduced into the body. Although it was once thought that excessive intake of calcium antacids could cause metabolic alkalosis, it has been found that this only occurs if they are administered concurrently with Kayexelate.[13]

Hydrogen ions may shift into cells due to hypokalemia, causing metabolic alkalosis. When hypokalemia occurs (i.e., low levels of potassium in the bloodstream), potassium shifts out of cells and into the bloodstream in an attempt to maintain a normal level of serum potassium for optimal cardiac function. However, as the potassium (K+) molecules move out of the cells, hydrogen (H+) ions then move into the cells from the bloodstream to maintain electrical neutrality. This transfer of ions causes the pH in the bloodstream to drop, causing metabolic alkalosis.[14]

A nurse may first suspect that a client has metabolic alkalosis due to a decreased respiratory rate (as the lungs try to retain additional CO2 to increase the acidity of the blood and resolve the alkalosis). The client may also be confused due to the altered pH level. The nurse should report signs of suspected metabolic alkalosis because uncorrected metabolic alkalosis can result in hypotension and cardiac dysfunction.[15]

Treatment is prescribed based on the ABG results and the suspected cause. For example, treat the cause of the vomiting, stop the gastrointestinal suctioning, or stop the administration of diuretics. If hypokalemia is present, it should be treated. If bicarbonate is being administered, it should be stopped. Clients with kidney disease may require dialysis.[16]

Analyzing ABG Results

Now that we’ve discussed the differences between the various acid-base imbalances, let’s review the steps to systematically interpret ABG results. Table 15.5b outlines the steps of ABG interpretation.

Table 15.5b Analyzing ABG Results[17],[18]

| Step | Action |

|---|---|

| Step 1: pH (normal 7.35-7.45) | If pH is out of range, determine if it is acidosis or alkalosis:

|

| Step 2: PaCO2 (normal 35-45 mmHg) |

**If the imbalance does not appear to be caused by a respiratory problem, move on to evaluate the HCO3. |

| Step 3: HCO3 (normal 22-26) |

|

| Step 4: Determine level of compensation | After determining the cause of the pH imbalance, determine if compensation is occurring.

|

Laws that govern the relationships between private entities.