Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Routine assessment of a patient’s mental status by registered nurses includes evaluating their level of consciousness, as well as their overall appearance, general behavior, affect and mood, general speech, and cognitive performance.[1],[2] See the “General Survey Assessment” chapter for more information about an overall mental status assessment.

Level of Consciousness

Level of consciousness refers to a patient’s level of arousal and alertness.[3] Assessing a patient’s orientation to time, place, and person is a quick indicator of cognitive functioning. Level of consciousness is typically evaluated on admission to a facility to establish a patient’s baseline status and then frequently monitored every shift for changes in condition.[4] To assess a patient’s orientation status, ask, “What is your name? Where are you? What day is it?” If the patient is unable to recall a specific date, it may be helpful to ask them the day of the week, the month, or the season to establish a baseline of their awareness level.

A normal level of orientation is typically documented as, “Patient is alert and oriented to person, place, and time,” or by the shortened phrase, “Alert and oriented x 3.”[5] If a patient is confused, an example of documentation is, “Patient is alert and oriented to self, but disoriented to time and place.”

There are many screening tools that can be used to further objectively assess a patient’s mental status and cognitive impairment. Common screening tools used frequently by registered nurses to assess mental status include the Glasgow Coma Scale, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), and the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).

Glasgow Coma Scale

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a standardized tool used to objectively assess and continually monitor a patient’s level of consciousness when damage has occurred, such as after a head injury or a cerebrovascular accident (stroke). See Figure 6.9[6] for an image of the Glasgow Coma Scale. Three primary areas assessed in the GCS include eye opening, verbal response, and motor response. Scores are added from these three categories to assign a patient’s level of responsiveness. Scores ranging from 15 or higher are classified as the best response, less than 8 is classified as comatose, and 3 or less is classified as unresponsive.

![]"glasgow-coma-scale-gcs-600w-309293585.jpg" by joshya on Shutterstock. All rights reserved. Imaged used with purchased permission Chart, with illustrations and labels, listing the glasgow coma scale](https://open.maricopa.edu/app/uploads/sites/683/2024/08/thumbnail_309293585-huge-1024x980.jpg)

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a standardized tool that is commonly used to assess patients suspected of experiencing an acute cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke).[7] The three most predictive findings that occur during an acute stroke are facial drooping, arm drift/weakness, and abnormal speech. Use the box below to view the stroke scale.

A commonly used mnemonic regarding assessment of individuals suspected of experiencing a stroke is “BEFAST.” BEFAST stands for Balance, Eyes, Face, Arm, and Speech Test.

- B: Does the person have a sudden loss of balance?

- E: Has the person lost vision in one or both eyes?

- F: Does the person’s face look uneven?

- A: Is one arm weak or numb?

- S: Is the person’s speech slurred? Are they having trouble speaking or seem confused?

- T: Time to call for assistance immediately

View the NIH Stroke Scale at the National Institutes of Health.

Mini-Mental Status Exam

The Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) is commonly used to assess a patient’s cognitive status when there is a concern of cognitive impairment. The MMSE is sensitive and specific in detecting delirium and dementia in patients at a general hospital and in residents of long-term care facilities.[8] Delirium is acute, reversible confusion that can be caused by several medical conditions such as fever, infection, and lack of oxygenation. Dementia is chronic, irreversible confusion and memory loss that impacts functioning in everyday life.

Prior to administering the MMSE, ensure the patient is wearing their glasses and/or hearing aids, if needed.[9] A patient can score up to 30 points by accurately responding and following directions given by the examiner. A score of 24-30 indicates no cognitive impairment, 18-23 indicates mild cognitive impairment, and a score less than 18 indicates severe cognitive impairment. See Figure 6.10[10] for an image of one of the questions on the MMSE regarding interlocking pentagons.

Visit the Oxford Medical Education website for more information about the Mini-Mental Status Exam.

!["InterlockingPentagons.svg" by Jfdwolff [2] is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 Illustration of two overlapping pentagon shapes](https://open.maricopa.edu/app/uploads/sites/683/2024/09/InterlockingPentagons.svg-3.png)

- Martin, D. C. The mental status examination. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK320/ ↵

- Giddens, J. F. (2007). A survey of physical examination techniques performed by RNs: Lessons for nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 83-87. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20070201-09 ↵

- Huntley, A. (2008). Documenting level of consciousness. Nursing, 38(8), 63-64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000327505.69608.35 ↵

- McDougall, G. J. (1990). A review of screening instruments for assessing cognition and mental status in older adults. The Nurse Practitioner, 15(11), 18–28. ↵

- Huntley, A. (2008). Documenting level of consciousness. Nursing, 38(8), 63-64. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000327505.69608.35 ↵

- “glasgow-coma-scale-gcs-600w-309293585.jpg” by joshya on Shutterstock. All rights reserved. Imaged used with purchased permission. ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). NIH stroke scale. https://www.stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm ↵

- McDougall, G. J. (1990). A review of screening instruments for assessing cognition and mental status in older adults. The Nurse Practitioner, 15(11), 18–28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6751405/ ↵

- Koder-Anne, D., & Klahr, A. (2010). Training nurses in cognitive assessment: Uses and misuses of the mini-mental state examination. Educational Gerontology, 36(10/11), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2010.485027 ↵

- “InterlockingPentagons.svg” by Jfdwolff[2] is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

Sutures are tiny threads, wire, or other material used to sew body tissue and skin together. They may be placed deep in the tissue and/or superficially to close a wound. The most commonly seen suture is the intermittent suture.

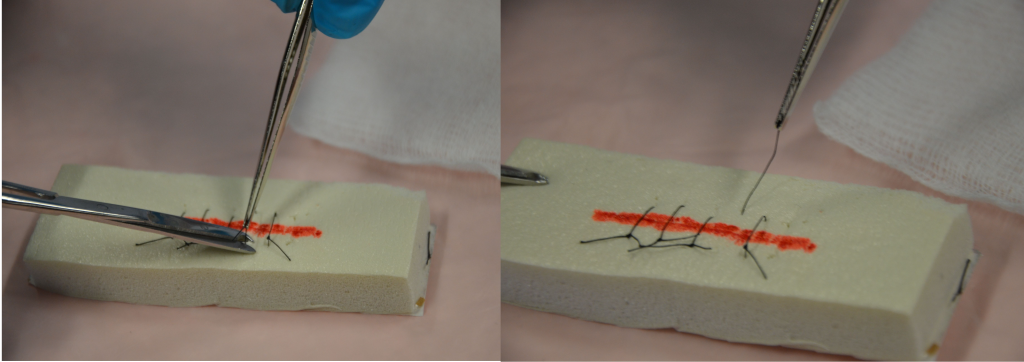

Sutures may be absorbent (dissolvable) or nonabsorbent (must be removed). Nonabsorbent sutures are usually removed within 7 to 14 days. Suture removal is determined by how well the wound has healed and the extent of the surgery. See Figure 20.32[1] for an example of suture removal. Sutures must be left in place long enough to establish wound closure with enough strength to support internal tissues and organs. If sutures are removed too early in the wound healing process, dehiscence can occur. The wound line must be observed for separations during the process of suture removal and the procedure stopped if there are any concerns.

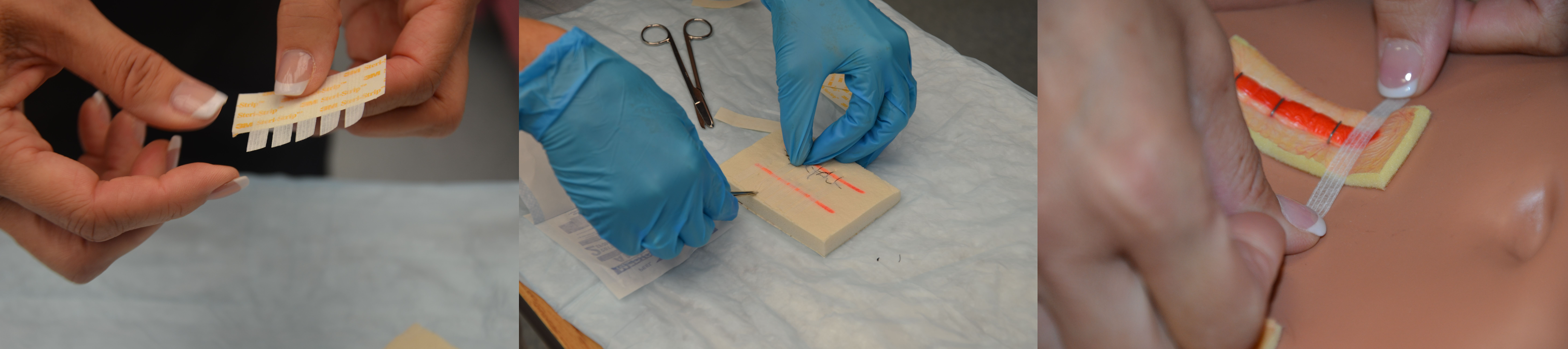

The health care provider must assess the wound to determine whether or not to remove the sutures and provide an order for the removal of sutures. Alternate sutures (every second suture) may be removed first, and then the remaining sutures removed after adequate approximation of the skin tissue is determined. If the wound is well-healed, all the sutures may be removed at the same time, but if there are concerns about approximation, the removal of the remaining sutures may be delayed for several days to avoid dehiscence. Steri-Strips may be applied prior to suture removal to lessen the chance of wound dehiscence. See Figure 20.33.[2]

Checklist for Intermittent Suture Removal

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Intermittent Suture Removal.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: sterile suture scissors, sterile dressing tray (to clean incision site prior to suture removal), nonsterile gloves, normal saline, Steri-Strips, and sterile outer dressing.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Confirm provider order and explain procedure to patient. Inform the patient that the procedure is not painful, but they may feel some pulling of the skin during suture removal.

- Prepare the environment, position the patient, adjust the height of the bed, and turn on the lights. Ensuring proper lighting allows for good visibility to assess the wound. Ensure proper body mechanics for yourself and create a comfortable position for the patient.

- Perform hand hygiene and put on nonsterile gloves.

- Place a clean, dry barrier on the bedside table. Add necessary supplies.

- Remove dressing and inspect the wound. Visually assess the wound for uniform closure of the wound edges, absence of drainage, redness, and swelling. After assessing the wound, decide if the wound is sufficiently healed to have the sutures removed. If there are concerns, discuss the order with the appropriate health care provider.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Put on a new pair of nonsterile or sterile gloves, depending on the patient's condition and the type, location, and depth of the wound.

- Irrigate the wound with sterile normal saline solution to remove surface debris or exudate and to help prevent specimen contamination. Alternatively, commercial wound cleanser may be used. This step reduces risk of infection from microorganisms on the wound site or surrounding skin. Cleaning also loosens and removes any dried blood or crusted exudate from the sutures and wound bed.

- To remove intermittent sutures, hold the scissors in your dominant hand and the forceps in your nondominant hand for dexterity with suture removal.

- Place a sterile 2" x 2" gauze close to the incision site to collect the removed suture pieces.

- Grasp the knot of the suture with the forceps and gently pull up the knot while slipping the tip of the scissors under the suture near the skin. Examine the knot.

- Cut under the knot as close as possible to the skin at the distal end of the knot:

- Never snip both ends of the knot as there will be no way to remove the suture from below the surface.

- Do not pull the contaminated suture (suture on top of the skin) through tissue.

- Grasp the knotted end of the suture with forceps, and in one continuous action pull the suture out of the tissue and place it on the sterile 2" x 2" gauze.

- Remove every second suture until the end of the incision line. Assess wound healing after removal of each suture to determine if each remaining suture will be removed. If the wound edges are open, stop removing sutures, apply Steri-Strips (using tension to pull wound edges together), and notify the appropriate health care provider. Remove remaining sutures on the incision line if indicated.

- Using the principles of no-touch technique, cut and place Steri-Strips along the incision line:

- Cut Steri-Strips so that they extend 1.5 to 2 inches on each side of the incision.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings of the incision. Report any concerns according to agency policy.