Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Pharmacokinetics – Examining the Interaction of Body and Drug

Overview

Pharmacokinetics is the term that describes the four stages of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of drugs. Drugs are medications or other substances that have a physiological effect when introduced to the body. There are four basic stages a medication goes through within the human body: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. This entire process is sometimes abbreviated ADME.

Absorption is the first stage of pharmacokinetics and occurs after medications enter the body and travel from the site of administration into the body’s circulation. Distribution is the second stage of pharmacokinetics. It is the process by which medication is spread throughout the body. Metabolism is the third stage of pharmacokinetics and involves the breakdown of a drug molecule. Excretion is the final stage of pharmacokinetics and refers to the process in which the body eliminates waste. Each of these stages is described separately in the following sections of this chapter.

Research scientists who specialize in pharmacokinetics must also pay attention to another dimension of drug action within the body: time. Scientists do not have the ability to visualize where a drug is going or how long it is active. To compensate, they use mathematical models and precise measurements of blood and urine to determine where a drug goes and how much of the drug (or breakdown product) remains after the body processes it. Other indicators, such as blood levels of liver enzymes, can help predict how much of a drug is going to be absorbed.

Principles of chemistry are also applied while studying pharmacokinetics because the interactions between drugs and body molecules represent a series of chemical reactions. Understanding the chemical encounters between drugs and biological environments, such as the bloodstream and the oily surfaces of cells, is necessary to predict how much of a drug will be metabolized by the body.

Pharmacodynamics refers to the effects of drugs in the body and the mechanism of their action. As a drug travels through the bloodstream, it exhibits a unique affinity for a drug-receptor site, meaning how strongly it binds to the site. Drugs and receptor sites create a lock and key system (see Figure 1.1[1]) that affect how drugs work and the presence of a drug in the bloodstream after it is administered. This concept is broadly termed as drug bioavailability.

The bioavailability of drugs is an important feature that chemists and pharmaceutical scientists keep in mind when designing and packaging medicines. However, no matter how effectively a drug works in a laboratory simulation, the performance in the human body will not always produce the same results, and individualized responses to drugs have to be considered. Although many responses to medications may be anticipated, a person’s unique genetic makeup may significantly impact their response to a drug. Pharmacogenetics is defined as the study of how people’s genes affect their response to medicines.[2]

- “Drug and Receptor Binding” by Dominic Slausen at Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medicines by Design by US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences and is available in the Public Domain. ↵

Evaluating the Effects

The nurse is responsible for assessing the client, monitoring lab values, and recognizing side effects and/or adverse effects of medications. Drug dosages should be verified to ensure all are within recommended safe ranges according to the client's current status, as well as for their potency.

Potency refers to the amount of the drug required to produce the desired effect. A drug that is highly potent may require only a minimal dose to produce a desired therapeutic effect, whereas a drug that has low potency may need to be given at much higher concentrations to produce the same effect. Consider the example of opioid versus nonopioid medications for pain control. Opioid medications often have a much higher potency in smaller doses to produce pain relief; therefore, the overall dose required to produce a therapeutic effect may be much less than that for other analgesics.

The nurse preparing to administer medications must also be cognizant of drug selectivity and monitor for potential side effects and adverse effects. Selectivity refers to the separation between the desired and undesired effects of a drug. Drugs that are selective will search out target sites to create a specific drug action, whereas nonselective drugs may impact many other types of cells and tissues, thus increasing the risk for unintended side effects and/or adverse effects. For example, in Chapter 4 selective and nonselective beta-blockers will be discussed. Selective beta-1 blockers search out specific receptors on the heart to create their effect, whereas nonselective beta-blockers may affect receptors in the lungs in addition to those in the heart, causing potential respiratory side effects like a cough.

A side effect occurs when the drug produces effects other than the intended effect. A side effect, although often unintended, is generally anticipated by the provider and is a known potential consequence of the medication therapy. Examples of common side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and drowsiness. In some situations, however, side effects may have a beneficial impact. For example, a side effect of hydrocodone is drowsiness. A client who is having difficulty sleeping due to pain and takes hydrocodone at bedtime may find the drowsiness beneficial in helping them fall asleep.

Conversely, unanticipated effects can occur from medications that are harmful to the client. These harmful occurrences are known as adverse effects. Adverse effects are relatively unpredictable, severe, and are reason to discontinue the medication.[1] For example, an adverse effect of ciprofloxacin is tendon rupture. Adverse effects should be reported to the pharmacy and tracked as a client safety concern according to agency policy.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario A

You are a nurse providing care for Mrs. Lyn, a 47-year-old client admitted with metastatic lung cancer receiving hospice care. The client's condition has declined significantly over the past week; she is actively dying. Over the last 24 hours, Mrs. Lyn has declined rapidly and is now unresponsive but appears to be resting comfortably. You enter the client's room and find Mr. Lyn weeping at the client's bedside.

- What actions would you take to comfort Mr. Lyn?

- Mrs. Lyn develops labored breathing. What medication is helpful to administer to treat dyspnea at end of life?

- Mrs. Lyn's breathing becomes less labored with medication, but her respiratory rate becomes irregular. Mr. Lyn tells the nurse, "My daughter lives six hours away and would like to be here when the time comes. How much longer does she have to live?" What is the nurse's best response?

- The daughter arrives and seems hesitant to talk to or touch her mother. What tasks can the nurse coach family members to do at the end of a client's life?

- Mrs. Lyn dies the following evening. What postmortem care should the nurse provide?

Scenario B

Terry, a 42-year-old male client, was recently diagnosed with advanced colon cancer and underwent a colon resection a few days ago. While changing his colostomy bag, he comments to the nurse, “I still can’t believe this is happening to me.”

- According to Kubler-Ross’ theory of grief/loss, what stage of grief is Terry currently experiencing?

- The nurse responds, “This is a difficult time for you.” Terry replies, “Yes, it is. My parents want me to do every kind of experimental treatment possible, but I just want to live my life until the time comes.” The nurse asks, “You have some tough decisions to make. Has anyone talked to you about palliative care yet?” Terry asks, “I’ve never heard of palliative care. What is it?” How would you explain palliative care to him?

- Terry states, “I don’t want my parents telling my doctor what to do. It is my decision.” The nurse asks, “Do you have any advance directives in place?” Terry responds, “What are advance directives?” How would you explain advance directives to Terry?

- The nurse identifies “Grieving related to anticipatory loss as evidenced by disbelief and feeling of shock” as a nursing diagnosis for Terry. Identify a SMART outcome.

- The nurse plans interventions to enhance Terry’s coping. List sample nursing interventions that may help Terry to cope with this new diagnosis.

Test your knowledge using this NCLEX Next Generation-style bowtie question. You may reset and resubmit your answers to this question an unlimited number of times.[2]

Provide objective data by using number values to explain outcomes.

Acute grief: Grief that begins immediately after the death of a loved one and includes the separation response and response to stress. (Chapter 17.2)

Advance directives: Legal documents that direct care when the client can no longer speak for themselves, including the living will and the health care power of attorney. (Chapter 17.2)

Anorexia: Loss of appetite or loss of desire to eat. (Chapter 17.4)

Anticipatory grief: Grief before a loss, associated with diagnosis of an acute, chronic, and/or terminal illness experienced by the client, family, and caregivers. Examples of anticipatory grief include actual or fear of potential loss or health, independence, body part, financial stability, choice, or mental function. (Chapter 17.2)

Bereavement period: The time it takes for the mourner to feel the pain of the loss, mourn, grieve, and adjust to the world without the presence of the deceased. (Chapter 17.2)

Burnout: A caregiver's diminished caring and cynicism that can be triggered by workplace demands, lack of resources to do work professionally and safely, interpersonal relationship stressors, or work policies that can lead to diminished caring and cynicism. Burnout may be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation. (Chapter 17.2)

Cachexia: Wasting of muscle and adipose tissue due to lack of nutrition. (Chapter 17.4)

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): Emergency treatment initiated when a client's breathing stops or their heart stops beating. It may involve chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, electric shocks to stop lethal cardiac rhythms, breathing tubes to open the airway, or cardiac medications. (Chapter 17.2)

Comfort care: Care that occurs when the client’s and medical team’s goals shift from curative interventions to symptom control, pain relief, and quality of life. (Chapter 17.2)

Compassion fatigue: A state of chronic and continuous self-sacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that affect a health care professional’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. (Chapter 17.2)

Complicated grief: Chronic grief, delayed grief, exaggerated grief, and masked grief are types of complicated grief. (Chapter 17.2)

Disenfranchised grief: Any loss that is not validated or recognized. (Chapter 17.2)

Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order: A medical order that instructs health care professionals not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a client's breathing stops or if the client's heart stops beating. (Chapter 17.2)

Fading away: A transition that families make when they realize their seriously ill family member is dying. (Chapter 17.2)

Grief: The emotional response to a loss, defined as the individualized and personalized feelings and responses that an individual makes to real, perceived, or anticipated loss. (Chapter 17.2)

Health care power of attorney: A legal document that identifies a trusted individual to serve as a decision maker for health issues when the client is no longer able to speak for themselves. (Chapter 17.2)

Hospice care: A type of palliative care that addresses care for clients who are terminally ill when a health care provider has determined they are expected to live six months or less. (Chapter 17.2)

Living will: A legal document that describes the client’s wishes if they are no longer able to speak for themselves due to injury, illness, or a persistent vegetative state. The living will addresses issues like ventilator support, feeding tube placement, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and intubation. (Chapter 17.2)

Loss: The absence of a possession or future possession with the response of grief and the expression of mourning. (Chapter 17.2)

Mourning: The outward, social expression of loss. Individuals outwardly express loss based on their cultural norms, customs, and practices, including rituals and traditions. (Chapter 17.2)

Normal grief: The common feelings, behaviors, and reactions to loss. (Chapter 17.2)

Palliative care: A broad philosophy of care defined by the World Health Organization as improving the quality of life of clients, as well as their family members, who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual.[3] (Chapter 17.2)

Rule of Double Effect: If the intent is good (i.e., relief of pain and suffering), then the act is morally justifiable even if it causes an unintended result of hastening death. (Chapter 17.5)

The American Nurses Association (ANA) is a professional organization that represents the interests of the nation's four million registered nurses and is at the forefront of improving the quality of health care for all.[4] The ANA establishes ethical and professional standards for nurses that also guide safe administration of medications. These code of ethics and professional standards are described in ANA publications titled Code of Ethics for Nurses and Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice.

Code of Ethics for Nurses

The ANA developed the Code of Ethics for Nurses as a guide for carrying out nursing responsibilities in a manner consistent with quality in nursing care and the ethical obligations of the profession.[5] Several provisions from the Code of Ethics impact how nurses should administer medication in an ethical manner. A summary of each provision from the Code of Ethics and how it pertains to medication administration is outlined below:

- Provision 1 focuses on respect for human dignity and the right for self-determination: “The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.”

- Provision 2 states, “The nurse's primary commitment is to the client…”[6] In health care settings, nurses often experience several competing loyalties, such as to their employer, to the doctor(s), to their supervisor, or to others on the health care team. However, the client should always receive the primary commitment of the nurse. Additionally, the client has the right to accept, refuse, or terminate any treatment, including medications.

- Provision 3 states, “The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient...”[7] This provision includes a nurse's responsibility to promote a culture of safety for clients. If errors occur, they must be reported, and nurses should ensure responsible disclosure of errors to clients. This also includes proper disclosure of questionable practices, such as drug diversion or impaired practice by any professional.

- Provision 4 involves authority, accountability, and responsibility by a nurse to follow legal requirements, such as state practice acts and professional standards of care.

- Provision 5 includes the responsibility of the nurse to promote health and safety.

- Provision 6 focuses on virtues that make a nurse a morally good person. For example, nurses are held accountable to use their clinical judgment to avoid causing harm to clients (maleficence) and to do good (beneficence). When administering medications, nurses should validate the medication is doing more “good” than “harm” (adverse or side effects).

- Provision 7 focuses on a nurse practicing within the professional standards set forth by their state nurse practice act, as well as standards established by professional nursing organizations.

- Provision 8 explains that a nurse must address the social determinants of health, such as poverty, education, safe medication, and health care disparities.[8]

Whenever a nurse provides client care, the ANA's Code of Ethics should be used as a guide for professional ethical behavior.

View the ANA's Code of Ethics for Nurses.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.2a

A nurse is preparing to administer medications to a client. While reviewing the chart, the nurse notices two medications with similar mechanisms of action have been prescribed by two different providers.

What is the nurse's best response?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

Standards and Scope of Practice

The ANA publishes Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. This resource establishes national standards for nurses and is updated regularly.[9]

The ANA defines the scope of nursing as “the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, facilitation of healing, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations.” A registered nurse (RN) is defined as an individual who is educationally prepared and licensed by a state to practice as a registered nurse. Nursing practice is characterized by the following tenets[10]:

- Caring and health are central to the practice of the registered nurse.

- Nursing practice is individualized to the unique needs of the health care consumer.

- Registered nurses use the nursing process to plan and provide individualized care for health care consumers.

- Nurses coordinate care by establishing partnerships to reach a shared goal of delivering safe, quality health care.

The ANA establishes Standards of Practice and Standards of Professional Performance in the Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice publication. State nurse practice acts further define the scope of practice of RNs and Licensed Practical Nurses/Vocational Nurses (LPNs/VNs) within each state. Nurse practice acts are further discussed in the “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration” section of this chapter.

The ANA's Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice publication can be purchased on the nursingworld.org website or borrowed from many libraries.

Standards of Practice

The ANA's Standards of Practice are authoritative statements of duties that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, or specialty, are expected to perform competently. Standards of Practice include assessment, diagnosis, outcome identification, planning, implementation, and evaluation (ADOPIE) components of providing client care, also known as the "nursing process." When nurses safely administer medication, all components of ADOPIE are addressed.

Assessment

The "Assessment" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.”[11] A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze client data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, when a nurse assesses multiple pieces of data for a hospitalized client with pain, this is considered part of a comprehensive pain assessment.

Diagnosis

The "Diagnosis" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[12] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the client's response to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are used to create the nursing care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.[13]

Outcomes Identification

The "Outcomes Identification" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.”[14] The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the client based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

Planning

The "Planning" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.”[15] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each client’s needs and concerns. Goals, expected outcomes, and nursing interventions are documented in the client’s nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, have access to it for continuity of care.[16]

Implementation

The "Implementation" Standard of Practice is defined as, "The nurse implements the identified plan.”[17] Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated to licensed practical nurses/vocational nurses (LPNs/VNs) or unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) with supervision. Interventions are also documented in the client’s electronic medical record as they are completed.[18]

The "Implementation" Standard of Professional Practice also includes the subcategories "Coordination of Care" and "Health Teaching and Health Promotion" to promote health and a safe environment.[19]

Coordination of Care

The ANA standard for coordination of care states, “The registered nurse coordinates care delivery.”[20] When ensuring medications are administered safely, the nurse collaborates with the client and the interprofessional health care team to meet mutually agreed upon outcomes. The nurse also engages the client in self-care to achieve their preferred goals for quality of life. For example, one client with chronic pain may have a pain management goal of "5" with their quality of life preference of having the ability to participate in social activities with friends but not experiencing burdensome side effect of medication. Another client with chronic pain may have a pain management goal of "0" with a quality of life preference of having no pain no matter what the side effects. The nurse advocates for these clients' goals and preferences with the interprofessional team.

Nurses also serve vital roles in ensuring safe transitions and continuity of care regarding clients' use of medications. Additional information about safe medication use and transitions of care is discussed in the "Preventing Medication Errors" section of this chapter.

Health Teaching and Health Promotion

When administering medications, nurses teach clients about the medications and potential side effects to promote optimal health. The ANA standard for health teaching and health promotion states, “The registered nurse employs strategies to teach and promote health and wellness.”[21] Specific behaviors related to teaching about medication are as follows[22]:

- Use health teaching and health promotion methods in collaboration with the client's values, beliefs, health practices, developmental level, learning needs, readiness and ability to learn, language preference, spirituality, culture, and socioeconomic status.

- Provide clients with information and education about intended effects and potential adverse effects of the plan of care.

- Provide anticipatory guidance to clients to promote health and prevent or reduce risk.

In the book Preventing Medication Errors by the Institute of Medicine (2007), the following are additional key national guidelines when teaching clients about safe use of their medications:

- Clients should maintain an active list of all prescription drugs, over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, and dietary supplements they are taking, the reasons for taking them, and any known drug allergies. Every provider involved in the medication-use process for a client should have access to this list.

- Clients should be provided information about side effects, contraindications, methods for handling adverse reactions, and sources for obtaining additional objective, high-quality information.[23]

Evaluation

The "Evaluation" Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[24] During evaluation, nurses assess the client and compare the findings against the initial assessment to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. Both the client’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care must be continuously evaluated and modified as needed.[25]

Read additional information about the nursing process in the "Nursing Process" chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Standards of Professional Performance

ANA's Standards of Professional Performance describe a competent level of behavior for nurses, including activities related to ethics, culturally congruent practice, communication, collaboration, leadership, education, evidence-based practice, and quality of practice.[26]

The ANA defines culturally congruent practice as the application of evidence-based nursing that is in agreement with the preferred cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of the health care consumer and other stakeholders. Cultural competence represents the process by which nurses demonstrate culturally congruent practice. Nurses must assess the cultural beliefs and practices of their clients and implement culturally congruent interventions when administering medications and teaching about them. Additional information about cultural implications for medication administration is further discussed in the “Cultural and Social Determinants Related to Medication Administration” section later in this chapter.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.2b

A nurse is preparing to administer metoprolol, a cardiac medication, to a client and implements the nursing process:

ASSESSES the vital signs prior to administration and discovers the heart rate is 48.

DIAGNOSES that the heart rate is too low to safely administer the medication per the parameters provided. Establishes the OUTCOME to keep the client's heart rate within normal range of 60-100.

PLANS to call the provider, as well as report this incident in the shift handoff report.

Implements INTERVENTIONS by withholding the metoprolol at this time, documenting the incident that the medication is withheld, and notifying the provider.

Continues to EVALUATE the client status throughout the shift after not receiving the metoprolol.

The nurse is providing health teaching to a client about the medication before discharge. The nurse provides a handout with instructions, as well as a list of the current medications.

What other information should be provided to the client?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” sections at the end of the book.

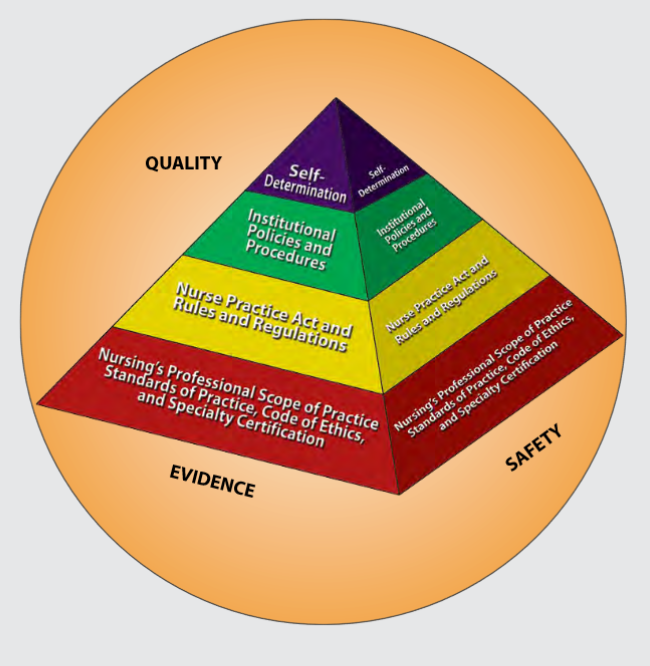

Figure 2.1 is an image from Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice by the ANA that illustrates how the scope of practice, standards of practice, and code of ethics form the “base” of nursing practice.[27] Nursing practice is further guided by the Nurse Practice Act in the state in which a nurse works, federal and state rules and regulations, institutional policies and procedures, and self-determination by the individual nurse. All these components are required to provide quality, safe client care that is evidence-based. These components will be further discussed in the remaining sections of this chapter.

NCLEX and the Clinical Judgment Model

The National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) is the national exam that graduates must pass successfully to obtain their nursing license after graduating from a nursing program of study. The NCLEX-PN is taken to become a licensed practical/vocational nurse (LPN/VN), and the NCLEX-RN is taken to become a licensed registered nurse (RN). The purpose of the NCLEX is to evaluate if a nursing graduate demonstrates the ability to provide safe, competent, entry-level nursing care. The NCLEX is developed by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN), an independent, nonprofit organization composed of the 50 state boards of nursing and other regulatory agencies.[28]

A new edition of the NCLEX was launched in April 2023 that contains “Next Generation” questions. The Next Generation NCLEX (NGN) assesses how well the candidate can think critically and use clinical judgment. The NCSBN defines clinical judgment as "the observed outcome of critical thinking and decision-making. It is an iterative process with multiple steps that uses nursing knowledge to observe and assess presenting situations, identify a prioritized client concern and generate the best possible evidence-based solutions in order to deliver safe client care."

The NCLEX uses the NCSBN's Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) to assess the candidate's ability to use safe clinical judgment when providing nursing care. Exam questions used to assess clinical judgment may be contained in a case study or as individual stand-alone items. A case study contains six questions that are associated with the same client scenario and addresses the following steps in clinical judgment[29]:

- Recognize cues: Identify relevant and important information from different sources (e.g., medical history, vital signs).

- Analyze cues: Organize and connect the recognized cues to the client’s clinical presentation.

- Prioritize hypotheses: Evaluate and prioritize hypotheses (based on urgency, likelihood, risk, difficulty, time constraints, etc.).

- Generate solutions: Identify expected outcomes and use hypotheses to define a set of interventions for the expected outcomes.

- Take action: Implement the solution(s) that address the highest priority.

- Evaluate outcomes: Compare observed outcomes to expected outcomes.

Throughout this book, learning activities are provided to assist students in learning how to apply the nursing process (i.e., ANA's Standards of Care) to answer NGN-style questions that evaluate clinical judgment. Some of these activities are written, with answers in the Answer Key at the end of the book, and others are interactive and require use of the online book.

Learning Objectives

- Identify cues related to alteration in comfort across the life span

- Identify standards of care for the client experiencing pain

- Identify interventions to increase client comfort

- Contribute to a plan of care for clients with comfort alterations

Pain is a universal sensation that everyone experiences, and acute pain is a common reason why clients seek medical care. Nurses work with the interdisciplinary team to assess and manage pain in a multidimensional approach to provide comfort and prevent suffering. This chapter will review best practices and standards of care for the assessment and management of pain.

Preventing medication errors has been a key target for improving safety since the 1990s. Despite error reduction strategies, implementing new technologies, and streamlining processes, medication errors remain a significant concern with error rates of 8%-25% during medication administration.[30] Furthermore, a substantial proportion of errors occur in hospitalized children due to the complexity of weight-based pediatric dosing.[31]

Several prevention initiatives have been developed to ensure safe medication administration such as the following strategies[32]:

- Routinely checking the rights of medication administration

- Standardizing communication such as "tall man lettering," alerts to "look alike-sound alike" drug names, avoidance of abbreviations, and standards for expressing numerical dosages

- Focusing on high-alert medications that have a higher likelihood of resulting in patient harm if involved in an administration error, such as anticoagulants, insulins, opioids, and chemotherapy agents

- Standardizing labelling of medication using visual cues as safeguards

- Optimizing nursing workflow to minimize errors, such as minimizing interruptions and double checking high alert medications

- Implementing technology like barcode medication administration and smart infusion pumps

Read the article "Medication Administration Errors" on the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) website.[33]

The Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals related to mediation administration were previously discussed in the "Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration" section of this chapter. This section will further discuss additional safety initiatives established by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), World Health Organization (WHO), Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), and Quality and Safe Education for Nurses (QSEN) to prevent medication errors.

Institute of Medicine

To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System Report

The national focus on reducing medical errors has been in place since the 1990s. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a historic report in 1999 titled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The report stated that errors caused between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths every year in American hospitals and over one million injuries. The IOM report called for a 50% reduction in medical errors over five years. Its goal was to break the cycle of inaction regarding medical errors by advocating for a comprehensive approach to improving patient safety. The IOM 1999 report changed the focus of patient safety from dispensing blame to improving systems.[34]

Preventing Medication Errors Report

In 2007 the IOM published a follow-up report titled Preventing Medication Errors, reporting that more than 1.5 million Americans are injured every year in American hospitals, and the average hospitalized client experiences at least one medication error each day. This report emphasized actions that health care systems, providers, funders, and regulators could take to improve medication safety. These recommendations included actions such as having all U.S. prescriptions written and dispensed electronically, promoting widespread use of medication reconciliation, and performing additional research on drug errors and their prevention. The report also emphasized actions that client can take to prevent medication errors, such as maintaining active medication lists and bringing their medications to appointments for review.[35]

The Preventing Medication Errors report included specific actions for nurses to improve medication safety. The box below summarizes key actions.[36]

Improving Medication Safety: Actions for Nurses

- Establish safe work environments for medication preparation, administration, and documentation; for instance, reduce distractions and provide appropriate lighting.

- Maintain a culture of rigorous commitment to principles of safety in medication administration (for example, consistently checking the rights of medication administration and also performing double checks with colleagues as recommended).

- Remove barriers and facilitate the involvement of client surrogates in checking the administration and monitoring the medication effects.

- Foster a commitment to clients’ rights as co-consumers of their care.

- Develop aids for clients or their surrogates to support self-management of medications.

- Enhance communication skills and team training to be prepared and confident in questioning medication orders and evaluating client responses to drugs.

- Actively advocate for the development, testing, and safe implementation of electronic health records.

- Work to improve systems that address "near misses" in the work environment.

- Realize they are part of a system and do their part to evaluate the efficacy of new safety systems and technology.

- Contribute to the development and implementation of error reporting systems and support a culture that values accurate reporting of medication errors.

World Health Organization: Medication Without Harm

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified “Medication Without Harm” as the theme for the third Global Patient Safety Challenge with the goal of reducing severe, avoidable medication-related harm by 50% over the next five years. As part of the Global Patient Safety Challenge: Medication Without Harm, the WHO has prioritized three areas to protect clients from harm while maximizing the benefit from medication[37]:

- Medication safety in high-risk situations

- Medication safety in polypharmacy

- Medication safety in transitions of care

Read more information about the WHO initiative called Medication Without Harm.

View the follow YouTube video explaining how to avoid harm from medications.

Medication Without Harm[38]

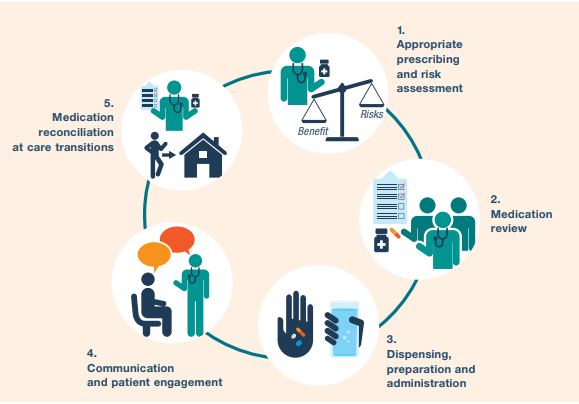

A summary of strategies to reduce harm and ensure medication safety is provided in Figure 2.3.[39]

Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations

The first priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative, medication safety in high-risk situations, includes the components of high-risk medications, provider-client relations, and systems factors.

High-Risk (High-Alert) Medications

High-risk medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant client harm when they are used in error.[40]

High-risk medication can be remembered using the mnemonic “A PINCH.” The information in the box below describes these medications included with the “A PINCH” mnemonic.

High-Risk Medication Group Examples of Medication

A: Anti-infective Amphotericin, aminoglycosides

P: Potassium & other electrolytes Injections of potassium & other electrolytes

I: Insulin All types of insulin

N: Narcotics & other sedatives Opioids, such as morphine; Benzodiazepines

C: Chemotherapeutic agents Methotrexate and vincristine

H: Heparin & anticoagulants Warfarin and enoxaparin

Note: Based on research, the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has expanded this list of high-risk medications. The updated list can be viewed in the box below.

Strategies for safe administration of high-alert medication include the following:

- Standardizing the ordering, storage, preparation, and administration of these products

- Improving access to information about these drugs

- Employing clinical decision support and automated alerts

- Using redundancies such as automated or independent double-checks when necessary

Provider-Patient Relations

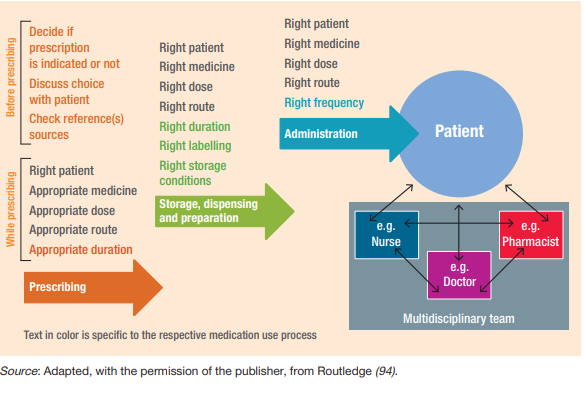

In addition to high-risk medications, a second component of medication safety in high-risk situations includes provider and client factors. This component relates to either the health care professional providing care or the client being treated. Even the most dedicated health care professional is fallible and can make errors. The act of prescribing, dispensing, and administering a medicine is complex and involves several health care professionals. The client should be the center of what should be a "prescribing partnership."[41] See Figure 2.4 for an illustration of the prescribing partnership.[42]

Life Span Considerations

Other risk factors can exist in specific clients across the life span. For example, adverse drug events occur most often at the extremes of life (in the very young and very old). In the older adult population, frail clients are likely to receive several medications concurrently, which adds to the risk of adverse drug events. In addition, the harm of some of these medication combinations may be synergistic, meaning the risk is greater when medications are taken together than the sum of the risks of individual agents. In neonates (particularly premature neonates), elimination routes through the kidney or liver may not be fully developed. The very young and very old are also less likely to tolerate adverse drug reactions, either because their homeostatic mechanisms are not yet fully developed, or they may have deteriorated. Medication errors in children, where doses may have to be calculated in relation to body weight or age, are also a source of major concern. Additionally, certain medical conditions predispose clients to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions, particularly renal or hepatic dysfunction and cardiac failure. Interprofessional strategies to address these potential harms are based on a systems approach with a "prescribing partnership" between the client, the prescriber, the pharmacist, and the nurse that includes verifying orders when concerns exist.

Systems Factors

In addition to high-risk medications and provider-patient relations, systems factors also contribute to medication safety in high-risk situations. Systems factors can contribute to error-provoking conditions for several reasons. The unit may be busy or understaffed, which can contribute to inadequate supervision or failure to remember to check important information. Interruptions during critical processes (e.g., administration of medicines) can also occur, which can have significant implications for patient safety. Tiredness and the need to multitask when busy or flustered can also contribute to error and can be compounded by poor electronic medical record design. Preparing and administering intravenous medications are also particularly error prone. Strategies for reducing errors include checking at each step of the medication administration process; preventing interruptions; using electronic provider order entry; and utilizing prescribing assessment tools, such as the Beers Criteria, to evaluate for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults.[43] The Beers Criteria is a list of potentially harmful medications or medications with side effects that outweigh the benefit of taking the medication.

Read additional information about the updated Beers Criteria by the American Geriatrics Society.

Medication Safety in Polypharmacy

The second priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety in polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is the concurrent use of multiple medications. Although there is no standard definition, polypharmacy is often defined as the routine use of five or more medications including over-the-counter, prescription, and complementary medicines.

As people age, they are more likely to suffer from multiple chronic illnesses and take multiple medications. It is essential to use a person-centered approach to ensure their medications are appropriate to gain the most benefits without harm and to ensure the client is part of the decision-making process. Appropriate polypharmacy is present when all medicines are prescribed for the purpose of achieving specific therapeutic objectives that have been agreed with the client; therapeutic objectives are actually being achieved or there is a reasonable chance they will be achieved in the future; medication therapy has been optimized to minimize the risk of adverse drug reactions; and the client is motivated and able to take all medicines as intended.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is present when one or more medications are prescribed that are no longer needed. One or more medications may no longer be needed because there is no evidence-based indication, the indication has expired or the dose is unnecessarily high, they fail to achieve the therapeutic objectives they were intended to achieve, one or the combination of several medications put the client at a high risk of adverse drug reactions, or the client is not willing or able to take the medications as intended.[44]

When clients transition across health care settings, medication review by nurses is essential to prevent harm caused by inappropriate polypharmacy. [45]

Review questions to address during a medication review in Chapter 2 of WHO's Medication Safety in Polypharmacy Technical Report.[46]

Medication Safety in Transitions of Care

The third priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety during transitions of care. View the interactive activity below to see how medications are reconciled during transitions of care from admission to discharge in a hospital setting.

Interactive Activity

"Medication Reconciliation Process" by E. Christman for Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0

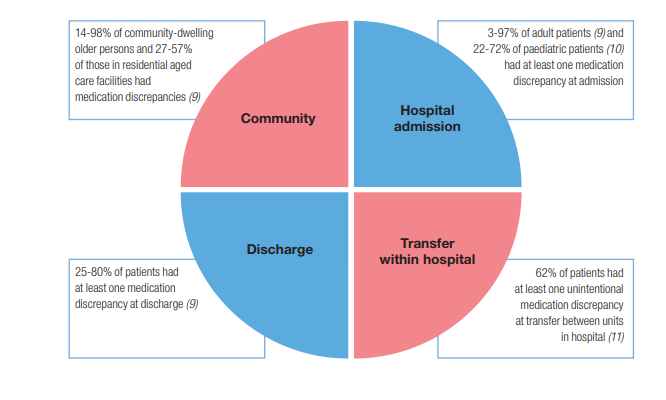

Medication errors can occur during transitions across settings. Figure 2.5[47] is an image from the World Health Organization showing ranges of percentage of errors that occur during common transitions of care.

Key strategies for improving medication safety during transitions of care include the following:

- Implementing formal structured processes for medication reconciliation at all transition points of care. Steps of effective medication reconciliation are to build the best possible medication history by interviewing the client and verifying with at least one reliable information source, reconciling and updating the medication list, and communicating with the client and future health care providers about changes in their medications.

- Partnering with clients, families, caregivers, and health care professionals to agree on treatment plans, ensuring clients are equipped to manage their medications safely, and ensuring clients have an up-to-date medication list.

- Where necessary, prioritizing clients at high risk of medication-related harm for enhanced support such as post-discharge contact by a nurse.[48]

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5a

A nurse is performing medication reconciliation for an elderly client admitted from home. The client does not have a medication list and cannot report the names, dosages, and frequencies of the medication taken at home.

What other sources can the nurse use to obtain medication information?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is respected as the gold standard for medication safety information. It is a nonprofit organization devoted entirely to preventing medication errors. ISMP collects and analyzes thousands of medication error and adverse event reports each year through its voluntary reporting program and then issues alerts regarding errors happening across the nation. The ISMP has established several prevention strategies for safe medication administration, including lists of high-alert medications, error-prone abbreviations to avoid, do not crush medications, look-alike and sound-alike drugs, and error-prone conditions that lead to error by nurses and student nurses. Each of these initiatives is further described below.[49]

Error-Prone Abbreviations

ISMP's List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations contains abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations that have been reported through the ISMP National Medication Errors Reporting Program as being frequently misinterpreted and involved in harmful medication errors. These abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations should never be used when communicating medical information. Note that this list has additional abbreviations than those contained in The Joint Commission's Do Not Use List of Abbreviations. Review the information below for the ISMP list of error-prone abbreviations to avoid. Some examples of abbreviations that were commonly used that should now be avoided are qd, qod, qhs, BID, QID, D/C, subq, and APAP.[50]

Strategies to avoid mistakes related to error-prone abbreviations include not using these abbreviations in medical documentation. Furthermore, if a nurse receives a prescription containing an error-prone abbreviation, it should be clarified with the provider and the order rewritten without the abbreviation.

Download the ISMP List of Error-Prone Abbreviations to Avoid PDF.

Do Not Crush List

The IMSP maintains a list of oral dosage medication that should not be crushed, commonly referred to as the “Do Not Crush” list. These medications are typically extended-release formulations.[51] Strategies for preventing harm related to oral medication that should not be crushed include requesting an order for a liquid form or a different route if the client cannot safely swallow the pill form.

Look-Alike and Sound-Alike (LASA) Drugs

ISMP maintains a list of drug names containing look-alike and sound-alike name pairs such as Adderall and Inderal. These medications require special safeguards to reduce the risk of errors and minimize harm.

Safeguards may include the following:

- Using both the brand and generic names on prescriptions and labels

- Including the purpose of the medication on prescriptions

- Changing the appearance of look-alike product names to draw attention to their dissimilarities

- Configuring computer selection screens to prevent look-alike names from appearing consecutively[52]

Download the ISMP's List of Confused Drug Names PDF.

Error-Prone Conditions That Lead to Student Nurse Related Error

When analyzing errors involving student nurses reported to the USP-ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program and the PA Patient Safety Reporting System, it appears that many errors arise from a distinct set of error-prone conditions or medications. Some student-related errors are similar in origin to those that seasoned licensed health care professionals make, such as misinterpreting an abbreviation, misidentifying drugs due to look-alike labels and packages, misprogramming a pump due to a pump design flaw, or simply making a mental slip when distracted. Other errors stem from system problems and practice issues that are rather unique to environments where students and hospital staff are caring together for clients. View the list of error-prone conditions that should be avoided using the following box.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5b

A nurse is preparing to administer insulin to a client. The nurse is aware that insulin is a medication on the ISMP list of high-alert medications.

What strategies should the nurse implement to ensure safe administration of this medication to the client?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project's vision is to “inspire health care professionals to put quality and safety as core values to guide their work.” QSEN began in 2005 and is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Based on the Institute of Medicine (2003) competencies for nursing, QSEN further defined these quality and safety competencies for educating nursing students:

- Patient-Centered Care

- Teamwork & Collaboration

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Quality Improvement

- Safety

- Informatics[53]

View the QSEN website.

Below are supplementary QSEN learning resources related to patient safety and preventing errors during medication administration.

The Josie King Story and Medical Errors[54]

Summary of Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

Medication administration by nurses is not just a task on a daily task list; it is a system-wide process in collaboration with other health care team members to ensure safe and effective treatment. As part of the medication administration process, the nurse must consider ethics, laws, national guidelines, and cultural/social determinants before administering medication to a client. The nurse is the vital “last stop” for preventing errors and potential harm from medications before they reach the client. A list of nursing considerations whenever administering medications is outlined below.

Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

BEFORE Administering Medication

Ethics

- Will this medication do more good than harm for this client at this point in time?

- Has the client (or the client's decision maker) had a voice in the decision-making process regarding use of this medication? Have they been informed about this medication and the potential risks/benefits to consider?

- If there are any ethical concerns, advocate for client rights and autonomy and contact the provider and/or pursue the proper chain of command.

Laws and National Guidelines

- Be sure the prescription/order contains the proper information according to CMS guidelines.

- Are there any FDA Boxed Warnings for this drug? If so, is the client aware of the risks and what to do if they occur? This discussion should be documented.

- Is this a controlled substance? If so, follow guidelines and agency policy for controlled substances in terms of counting, wasting, and disposal. For prescriptions for outpatient use, advocate that Prescription Drug Monitoring Program guidelines are followed.

- Be aware of signs of drug diversion in other health care team members and follow up appropriately in the chain of command. You can also directly submit an online tip to the DEA at Rx Abuse Online Reporting.

- Follow the Joint Commission “SPEAK UP” guidelines if you have any concerns about the safe use of this medication, including, but not limited to:

- Unclear or “do not use” abbreviations

- Strategies for look alike-sound alike medications

- Any other concerns for error

- Follow your state's practice act regarding Scope of Practice and Rules of Conduct. Is administering this medication appropriate for your scope of practice and for this client? If not, protect your client from harm and your nursing license by notifying the appropriate contacts within your agency.

- Is this medication administration occurring during a transition of care from unit to unit, home to agency, or in preparation for discharge? If so, be sure proper medication reconciliation has been completed.

DURING Administration

- Use the nursing process as you ASSESS if this drug is appropriate to administer at this time and PLAN continued monitoring. Consider life span and disease process implications. If you NOTICE any findings that this medication may not be appropriate at this time for this client, withhold the medication and contact the provider.

- Assess if there are any cultural or social determinants that will impact the client's ability to use these medications safely and effectively. IMPLEMENT appropriate accommodations as needed and notify the provider.

- Follow The Joint Commission's National Patient Safety Goals as you correctly identify the client and follow guidelines to use medicines safely.

- If this is a high-alert medication, follow recommendations for safe administration (such as adding a second RN check, etc.).

- Reduce distractions in your environment as you prepare and administer medications.

- Do not crush medications unless safe to do so.

- Follow standards set by The Joint Commission and CMS:

- Checking rights of medication administration before administering any medication to a client

- Educate the client about their medication

- Dispose of unused controlled substances appropriately

- Document appropriately

AFTER Administration

- Continue to EVALUATE the client for potential side effects/adverse effects, as well as therapeutic effects of the medications.

- Document and verbally share your findings during handoff reports for safe continuity of care.

- If an error occurs, file an incident report and participate in root cause analysis to determine how to prevent it from happening again.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss federal and state laws, regulations, and guidelines for safe medication administration

- Identify drug administration guidelines within the State Nurse Practice Act

- Identify ethical responsibilities related to medication administration

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with controlled substances

- Identify nursing responsibilities to prevent and respond to medication errors

- Explain how nursing response reflects respect for a client's rights and responsibilities with drug therapy

- Outline nursing actions within the scope of nursing practice as they relate to the administration of medication

- Demonstrate patient-centered care during medication administration by respecting a client's gender, psychosocial, and cultural needs

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with safe medication administration

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with health teaching and health promotion[55]

Medication administration is an essential task nurses perform while providing client care. However, safe medication administration is more than just a nursing task; it is a process involving several members of the health care team, as well as legal, ethical, social, and cultural issues. The primary focus of effective medication administration by all health professionals is patient safety. Although many measures have been put into place over the past few decades to promote improved patient safety, medication errors and adverse effects continue to be a common event. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that unsafe medication practices and medication errors are a leading cause of injury and avoidable harm in health care systems across the world. Globally, the cost associated with medication errors has been estimated at $42 billion USD annually.[56] This chapter will examine the legal and ethical foundations of medication administration by nurses, as well as the practice standards and cultural and social issues that must be considered to ensure safe and effective administration of medication.

Learning Objectives

- Discuss federal and state laws, regulations, and guidelines for safe medication administration

- Identify drug administration guidelines within the State Nurse Practice Act

- Identify ethical responsibilities related to medication administration

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with controlled substances

- Identify nursing responsibilities to prevent and respond to medication errors

- Explain how nursing response reflects respect for a client's rights and responsibilities with drug therapy

- Outline nursing actions within the scope of nursing practice as they relate to the administration of medication

- Demonstrate patient-centered care during medication administration by respecting a client's gender, psychosocial, and cultural needs

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with safe medication administration

- Identify nursing responsibilities associated with health teaching and health promotion[57]

Medication administration is an essential task nurses perform while providing client care. However, safe medication administration is more than just a nursing task; it is a process involving several members of the health care team, as well as legal, ethical, social, and cultural issues. The primary focus of effective medication administration by all health professionals is patient safety. Although many measures have been put into place over the past few decades to promote improved patient safety, medication errors and adverse effects continue to be a common event. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that unsafe medication practices and medication errors are a leading cause of injury and avoidable harm in health care systems across the world. Globally, the cost associated with medication errors has been estimated at $42 billion USD annually.[58] This chapter will examine the legal and ethical foundations of medication administration by nurses, as well as the practice standards and cultural and social issues that must be considered to ensure safe and effective administration of medication.