Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Three major concepts associated with grieving are loss, grief, and mourning. Loss is the absence of a possession or future possession with the response of grief and the expression of mourning. The feeling of loss can be associated with the loss of health, changes in relationships and roles, and eventually the loss of life. After a client dies, the family members and other survivors experience loss.[1]

Grief is the emotional response to a loss, defined as the individualized and personalized feelings and responses that an individual makes to real, perceived, or anticipated loss. These feelings may include anger, frustration, loneliness, sadness, guilt, regret, and peace. Grief affects survivors physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually. The grief process is not orderly and predictable. Emotional fluctuation is normal and expected. There are times when the person experiencing the loss feels in control and accepting, and there are other times when the loss feels unbearable and they feel out of control.[2] See Figure 17.1[3] for an image of an individual in a cemetery who may be experiencing grief.

Mourning is the outward, social expression of loss. Individuals outwardly express loss based on their cultural norms, customs, and practices, including rituals and traditions. Some cultures may be very emotional and verbal in their expression of loss, such as wailing or crying loudly. Other cultures are stoic and show very little reaction to loss. Culture also dictates how long one mourns and how the mourners “should” act. The expression of loss is also affected by an individual’s personality and previous life experiences.[4]

Types of Grief

There are five different categories of grief: anticipatory grief, acute grief, normal grief, disenfranchised grief, and complicated grief.

Anticipatory Grief

Anticipatory grief is defined as grief before a loss, associated with diagnosis of an acute, chronic, and/or terminal illness experienced by the client, family, or caregivers. Examples of anticipatory grief include actual or fear of potential loss of health, independence, body part, financial stability, choice, or mental function.[5]

Sometimes anticipatory grief starts at the time of a terminal diagnosis and can proceed until the person dies. Clients and their family members can feel anticipatory loss. The client often anticipates the loss of independence, function, or comfort, which can cause significant pain and anxiety if not given the proper support. A client may also have concrete fears such as the loss of the ability to drive, live independently, or maintain their current body image. They may also have grief regarding the loss of anticipated family experiences, such as celebrating the marriage of a child, the birth of a grandchild, an anniversary, or another significant life event. The family often starts grieving for the loss of their loved one before they die as they envision their life without their loved one in it. This type of grief has been shown to help cushion a person’s bereavement reaction.[6]

Acute Grief

Acute grief begins immediately after the death of a loved one and includes the separation response and response to stress. During this period of acute grief, the bereaved person may be confused and/or uncertain about their identity or social role. They may disengage from their usual activities and experience disbelief and shock that their loved one is gone.[7] See Figure 17.2[8] for an image of a sculpture depicting acute grief.

Normal Grief

Normal grief includes the common feelings, behaviors, and reactions to loss. Normal grief reactions to a loss can include the following:

- Physical symptoms such as hollowness in the stomach, tightness in the chest, weakness, heart palpitations, sensitivity to noise, breathlessness, tension, lack of energy, and dry mouth

- Emotional symptoms such as numbness, sadness, fear, anger, shame, loneliness, relief, emancipation, yearning, anxiety, guilt, self-reproach, helplessness, and abandonment

- Cognitive symptoms such as a state of depersonalization, confusion, inability to concentrate, dreams of the deceased, idealization of the deceased, or a sense of presence of the deceased

- Behavioral signs such as impaired work performance, crying, withdrawal, overreactivity, changed relationships, or avoidance of reminders of the deceased[9]

Acute grieving may take months and but can also take years, depending on the loss. No one ever truly gets over the loss, but there is an eventual reconnection with the world of the living as the relationship with the deceased changes.[10]

Disenfranchised Grief

Disenfranchised grief is grief over any loss that is not validated or recognized. Those affected by this type of grief do not feel the freedom to openly acknowledge their grief. Individuals at risk for disenfranchised grief are those who have lost loved ones to stigmatized illnesses or events, such as AIDS. Mothers and/or fathers may grieve over terminated pregnancies or stillborn babies. The loss of a previously severed relationship or divorce can contribute to this type of grief because the individual may not be able to mourn openly due to the circumstances surrounding the relationship.

Complicated Grief

Complicated grief occurs when there is interference in the grieving process leading to a prolonged, more intense grieving. There is often preoccupation with the circumstances of the loss, which may manifest as feelings of guilt regarding the situation around the loss. There is generally a negative focus on the loss, which overrides any positive emotions the person may feel. Complicated grieving can cause significant distress, impaired functioning, and suicidal thinking.[11] Complicated grief is seen in 10-20% of individuals experiencing the death of a romantic partner and with higher estimates for parents who have lost a child. According to the ELNEC, there are four types of complicated grief, including chronic grief, delayed grief, exaggerated grief, and masked grief. Risk factors for developing complicated grief include sudden or traumatic death, suicide, homicide, a dependent relationship with the deceased, chronic illness, death of a child, multiple losses, unresolved grief from prior losses, concurrent stressors, witnessing a difficult dying process such as pain and suffering, lack of support systems, and lack of a faith system. Complicated grief may require professional assistance depending on its severity. Factors that contribute to complicated grief in older adults include lack of a support network, concurrent losses, poor coping skills, and loneliness.[12]

- Chronic Grief: Normal grief reactions that do not subside and continue over very long periods of time.

- Delayed Grief: Normal grief reactions that are suppressed or postponed by the survivor consciously or unconsciously to avoid the pain of the loss.

- Exaggerated Grief: An intense reaction to grief that may include nightmares, delinquent behaviors, phobias, and thoughts of suicide.

- Masked Grief: Grief that occurs when the survivor is not aware of behaviors that interfere with normal functioning as a result of the loss. For example, an individual cancels lunch with friends so they can go to the cemetery daily to visit their loved one’s grave.[13]

Stages of Grief

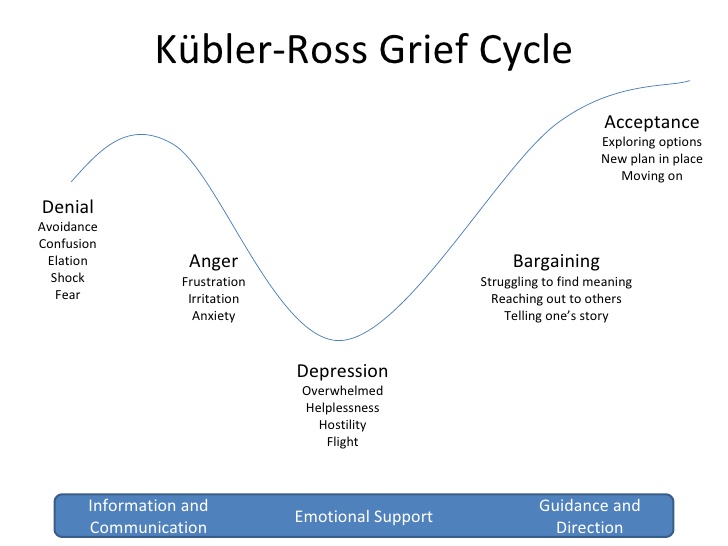

There are several stages of grief that may occur following a loss. It can be helpful for nurses to have an understanding of these stages to recognize the emotional reactions as symptoms of grief so they can support clients and families as they cope with loss. Famed Swiss psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross identified five main stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying.[14] Clients and families may experience these stages along a continuum, move randomly and repeatedly from stage to stage, or skip stages altogether. There is no one correct way to grieve, and an individual’s specific needs and feelings must remain central to care planning.

Kuber-Ross identified that clients and families demonstrate various characteristic responses to grief and loss. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, commonly referred to by the mnemonic “DABDA.” See Figure 17.3[15] for an illustration of the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle. Keep in mind that these stages of grief not only occur due to loss of life, but also occur due to significant life changes such as divorce, loss of friendships, loss of a job, or diagnosis with a chronic or terminal illness.[16]

View the beginning of this YouTube video clip[17] from the movie Steel Magnolias that shows a mother demonstrating stages of the grieving process.

Denial

Denial occurs when the individual refuses to acknowledge the loss or pretends it isn’t happening. This stage is characterized by an individual stating, “This can’t be happening.” The feeling of denial is self-protective as an individual attempts to numb overwhelming emotions as they process the information. The denial process can help to offset the immediate shock of a loss. Denial is commonly experienced during traumatic or sudden loss or if unexpected life-changing information or events occur. For example, a client who presents to the physician for a severe headache and receives a diagnosis of terminal brain cancer may experience feelings of denial. See Figure 17.4[18] for an image of a person depicting reaction to unexpected news with denial.

Anger

Anger in the grief process often masks pain and sadness. The subject of anger can be quite variable; anger can be directed to the individual who was lost, internalized to self, or projected toward others. Additionally, an individual may lash out at those uninvolved with the situation or have bursts of anger that seemingly have no apparent cause. Health care professionals should be aware that anger may often be directed at them as they provide information or provide care. It is important that health care team members, family members, and others who become the target of anger recognize that the anger and emotion are not a personal attack, but rather a manifestation of the challenging emotions that are a part of the grief process. If possible, the nurse can provide supportive presence and allow the client or family member time to vent their anger and frustration while still maintaining boundaries for respectful discussion. Rather than focusing on what to say or not to say, allowing a safe place for a client or family member to verbalize their frustration, sorrow, and anger can offer great support. See Figure 17.5[19] for an image of a child depicting anger.

Bargaining

Bargaining can occur during the grief process in an attempt to regain control of the loss. When individuals enter this phase, they are looking to find ways to change or negotiate the outcome by making a deal. Some may try to make a deal with God or their higher power to take away their pain or to change their reality by making promises to do better or give more of themselves if only the circumstances were different. For example, a client might say, “I promised God I would stop smoking if He would heal my wife’s lung cancer.”

Depression

Feelings of depression can occur with intense sadness over the loss of a loved one or the situation. Depression can cause loss of interest in activities, people, or relationships that previously brought one satisfaction. Additionally, individuals experiencing depression may experience irritability, sleeplessness, and loss of focus. It is not uncommon for individuals in the depression phase to experience significant fatigue and loss of energy. Simple tasks such as getting out of bed, taking a shower, or preparing a meal can feel so overwhelming that individuals simply withdraw from activity. In the depression phase, it can be difficult for individuals to find meaning, and they may struggle with identifying their own sense of personal worth or contribution. Depression can be associated with ineffective coping behaviors, and nurses should watch for signs of self-medicating through the use of alcohol or drugs to mask or numb depressive feelings. See Figure 17.6[20] for an image of a person depicting feelings of depression.

Acceptance

Acceptance refers to an individual understanding the loss and knowing it will be hard but acknowledging the new reality. The acceptance phase does not mean absence of sadness but is the acknowledgement of one’s capabilities in coping with the grief experience. In the acceptance phase, individuals begin to reengage with others, find comfort in new routines, and even experience happiness with life activities again. See Figure 17.7[21] of an image of a person depicting acceptance.

Grief Tasks

Kubler-Ross’s grief stages describe many feelings that individuals commonly experience while grieving loss. Other experts also describe the grieving process in terms of tasks that one must accomplish. These tasks include notification and shock, experiencing the loss, and reintegration.[22]

- Notification and shock: This phase occurs when a person first learns of the loss and experiences feelings of numbness or shock. The person may isolate themselves from others while processing this information. The first task for the person to complete is to acknowledge the reality of the loss by assessing and recognizing the loss.

- Experiencing the loss: The second task involves experiencing the loss emotionally and cognitively. The person must work through the pain by reacting to, expressing, and experiencing the pain of separation and grief.

- Reintegration: The third task involves reorganization and restructuring of family systems and relationships by adjusting to the environment without the deceased. The person must form a new reality without the deceased and adapt to a new role while also retaining memories of the deceased.[23]

As a nurse, you can greatly assist clients and family members as they move through the grieving process by being willing and committed to spending time with them. Listen to their stories, be present, and bear witness to their pain. Remember that you cannot fix everything, but taking time to assess their symptoms of grief helps you identify other resources for support.

Palliative Care and Hospice

Palliative care and hospice care are specialty care areas related to the care of clients and their families experiencing loss and the grieving process.

Palliative care is a broad philosophy of care defined by the World Health Organization as improving the quality of life of clients, as well as their family members, who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual.[24] In the United States, palliative care is further described as, “Patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care occurs throughout the continuum of care and involves the interdisciplinary team collaboratively addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and facilitating patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.”[25] Palliative care focuses on comfort and quality of life but also includes continuing curative treatment such as dialysis, chemotherapy, and surgery.

Hospice care is a type of palliative care that addresses care for clients who are terminally ill when a health care provider has determined they are expected to live six months or less. Like palliative care, hospice provides comprehensive comfort care and support for the family, but in hospice, curative treatments are stopped. It is based on the idea that dying is part of the normal life cycle and supports the client and family through the dying and grief process. It also supports the surviving family members through the bereavement process. Hospice care does not hasten death but focuses on providing comfort while allowing a natural death. Symptoms control, including pain relief, and quality of life are of utmost importance.

Many clients decide to receive hospice care at home with the support of family, nurses, and hospice staff, but hospice services are also available across a variety of settings such as long-term care, assisted living facilities, hospitals, and prisons. In the United States, older adults enrolled in Medicare can choose to receive hospice care and stop receiving curative treatment. It is important to remember that stopping curative treatment does not mean discontinuing all medical treatment. For example, a client with cancer who is no longer responding to chemotherapy can decide to enter hospice care and focus on comfort and quality of life. The chemotherapy treatment will stop, but other medical care, such as blood pressure medications or antibiotics to treat infection, will continue as long as they are helpful in promoting quality of life. Medicare will also pay for all related home durable medical equipment (such as a hospital bed and home oxygen therapy equipment) and all medications related to the terminal diagnosis (including pain medications).[26],[27] See Figure 17.8[28] for an image of a client receiving hospice care.

Unfortunately, instead of viewing hospice as a care option to promote quality of life and reduce suffering, many clients and their families associate hospice care with “giving up,” or as a “death sentence,” and are resistant to this type of care. For this reason, many health care teams advocate the implementation of palliative care until clients and their family members are ready to discuss hospice care.

When a client and their family members make the decision to implement home hospice, their desire is for the client to comfortably spend their final days in their home environment. However, if the client’s condition later becomes challenging for family members to manage at home, it can be very difficult to consider transferring the client to a hospice inpatient unit at that time. It is often helpful to encourage clients and family members to tour alternative care agencies when considering hospice and be prepared if this decision is later warranted.

Comfort Care

Comfort care is a term commonly used in the acute care setting that is similar to palliative care and hospice. Comfort care occurs when the clients and medical team’s goals shift from curative intervention to symptom control, pain relief, and quality of life. However, there is no formal admission to hospice or palliative care that can impact insurance coverage. Rather than focusing on aggressive medical intervention, the focus changes to symptom control to provide the client with the greatest degree of comfort possible as they approach their end of life. When comfort care is ordered by the provider, many interventions are eliminated to promote comfort, such as administering medications (with the exception of analgesics or antianxiety medications), monitoring vital sign monitoring, or performing blood draws or other invasive procedures.

Read more about the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care’s Palliative Care Guidelines.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

End-of-life care often includes unique complexities for the client, family, and nurse. There may be times when what the physician or nurse believes to be the best treatment conflicts with what the client desires. There may also be challenges related to decision-making that cause disagreements within a family or cause conflict with the treatment plan. Additional challenging factors include availability of resources and insurance company policies and programs.

Despite these complexities, it is important for the nurse to honor and respect the wishes of the client. Despite any conflicts in decision-making among health care providers, family members, and the client, the nurse must always advocate for the client’s wishes. Nurses should also be aware of the practice guidelines for ethical dilemmas stated in the American Nurses Association’s Standards of Professional Nursing Practice and Code of Ethics.[29],[30] These resources assist the nurse in implementing expected behaviors according to their professional role as a nurse.

If complex ethical dilemmas occur, many organizations have dedicated ethics committees that offer support, guidance, and resources for complex ethical decisions. These committees can serve as support systems, share resources, provide legal insight, and make recommendations for action. The nurse should feel supported in raising concerns within their health care organization if they believe an ethical dilemma is occurring.

Review ANA’s Code of Ethics.

Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Advance Directives

Additional legal considerations when providing care at the end of life are do-not-resuscitate orders (DNR) orders and advance directives. A do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is a medical order that instructs health care professionals not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a client’s breathing stops or their heart stops beating. The order is only written with the permission of the client (or the client’s health care power of attorney, if activated.) Ideally, a DNR order is set up before a critical condition occurs. CPR is emergency treatment provided when a client’s blood flow or breathing stops that may involve chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, electric shocks to stop lethal cardiac rhythms, breathing tubes to open the airway, or cardiac medications. The DNR order only refers to not performing CPR and is recorded in a client’s medical record. It is crucial to understand that with a DNR order, clients are still entitled to medical treatment, such as antibiotics, IVs, and medications, and as such, treatment should be rendered when abnormalities are noted or anticipated. Wallet cards, bracelets, or other DNR documents are also available to have at home or in nonhospital settings. The decision to implement a DNR order is typically very difficult for a client and their family members to make.[31] Many people have unrealistic ideas regarding the success rates of CPR and the quality of life a client experiences after being revived, especially for clients with multiple chronic diseases or those receiving palliative care. For example, a recent study found the overall rate of survival leading to hospital discharge for someone who experiences cardiac arrest is about 10.6 percent.[32] Nurses can provide up-to-date health teaching regarding CPR and its effectiveness based on the client’s current condition and facilitate discussion about a DNR order.

Advance directives are legal documents that direct care when the client can no longer speak for themselves and include a health care power of attorney and a living will. The health care power of attorney legally identifies a trusted individual to serve as a decision maker for health issues when the client is no longer able to speak for themselves. It is the responsibility of this designated individual to carry out care actions in accordance with the client’s wishes. A health care power of attorney can be a trusted family member, friend, or colleague who is of sound mind and is over the age of 18. They should be someone who the client is comfortable expressing their wishes to and someone who will enact those desired wishes on the client’s behalf.

The health care power of attorney should also have knowledge of the client’s wishes outlined in their living will. A living will is a legal document that describes the client’s wishes if they are no longer able to speak for themselves due to injury, illness, or a persistent vegetative state. The living will addresses issues like ventilator support, feeding tube placement, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and intubation. It is a vital means of ensuring that the health care provider has a record of one’s wishes. However, the living will cannot feasibly cover every possible potential circumstance, so the health care power of attorney is vital when making decisions outside the scope of the living will document.

Read more about advance care planning at the National Institute on Aging and at Honoring Choices Wisconsin.

![]() Nurses must understand the health care practice legalities for the state in which they practice nursing. There can be practice issues in various states that raise additional ethical complexities for the practicing nurse. For example, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and New Mexico all have laws that allow clients to participate in assisted dying practices involving assisted suicide or active euthanasia. In assisted suicide, the client is provided the means to carry out suicide such as a lethal dose of medication. Active euthanasia involves someone other than the client carrying out action to end a person’s life. Most nursing organizations prevent a nurse from participating in assisted dying practices. Nurses must be aware of the Nurse Practice Act in their state and the legalities and ethical challenges of nursing actions surrounding complex issues such as assisted suicide, active euthanasia, and abortion.

Nurses must understand the health care practice legalities for the state in which they practice nursing. There can be practice issues in various states that raise additional ethical complexities for the practicing nurse. For example, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and New Mexico all have laws that allow clients to participate in assisted dying practices involving assisted suicide or active euthanasia. In assisted suicide, the client is provided the means to carry out suicide such as a lethal dose of medication. Active euthanasia involves someone other than the client carrying out action to end a person’s life. Most nursing organizations prevent a nurse from participating in assisted dying practices. Nurses must be aware of the Nurse Practice Act in their state and the legalities and ethical challenges of nursing actions surrounding complex issues such as assisted suicide, active euthanasia, and abortion.

Caring for the Family of a Dying Client

When caring for a client who is nearing the end of life, the family members require nursing care as well. Fading away is a transition that families make when they realize their seriously ill family member is dying. Although they may have been previously told by a health care provider that their loved one would die from the illness, there is often a sudden realization their family member “is not going to get any better” when their health begins to significantly decline. With this realization comes the transition of fading away.[33]

There are various dimensions that both clients and family members experience during this fading away process:

- Redefining: There is a shift for both clients and families from “what used to be” to “what is now.”

- Burdening: As clients become more dependent, they may feel as if they are a burden to their family–physically, financially, emotionally, socially, and spiritually. Yet, family members typically do not feel the care they are providing is a burden, but rather, “something you do for someone you love.”

- Searching for Meaning: Clients journey inward, seek spiritual reflection, and become more connected to important family members and friends. Family members may search for meaning inwardly through spiritual reflection or explore for meaning with family members and friends.

- Living Day to Day: Clients who eventually find meaning in their illness live each day with a more positive attitude. Family members who try to “make the best of it” make efforts to enjoy the limited time left with their loved one.

- Preparing for Death: Clients often want to leave a legacy. Spouses often want to meet every need of their ill spouse. Clients and family members may begin to make prearrangements for the funeral, as well as get their will and other financial matters in order.

- Contending with Change: Clients and their family members change roles, social patterns, and work patterns. They know the life they used to have will soon be gone.[34]

Nurses can assist clients and family members during the fading away transition by being present and actively listening.

Caregiver Support

Most clients with chronic illness have family caregivers that are an extension of the health care team and work around the clock, all days of the week. They typically provide 70-80% of the care at home. It is important for nurses to assess the caregiver when seeing them with the client in the home, clinic, hospital, or long-term setting and provide encouragement. It is helpful to acknowledge their work is very difficult and to praise them for their efforts.[35] See Figure 17.9[36] for an image of a mother acting as caregiver and supporting her son’s health.

Research shows caregivers often have the following needs[37]:

- Support, assistance, and practical help (e.g., finding others to assist with grocery shopping, going to the pharmacy, and food preparation)

- Honest conversations with the health care team

- Assurance their loved one is being honored

- Inclusion in decision-making

- Desire to be listened to and their concerns heard

- Remembrance as a good and compassionate caregiver

- Assurance that they did all they possibly could for their loved one

Assess the caregiver’s needs for further assistance, as well as their social support network. Assess their physical needs, sleep patterns, and ability to perform other responsibilities. Watch for signs of declining health, clinical depression, or signs of increased use of alcohol and drugs. Listen to the caregiver’s stories and provide presence, active listening, and touch. Assist them in identifying and using support systems and refer them to resources and support groups in the community as needed.[38]

Cultural Considerations Regarding Death

When assessing clients, family members, and caregivers, it is important to respect their values, beliefs, and traditions related to health, illness, family caregiver roles, and decision-making. Information gathered through this comprehensive assessment is used to develop a nursing care plan that incorporates culturally sensitive resources and strategies to meet the needs of clients and their family members.[39] See Figure 17.10[40] for an image depicting a community grieving.

Nurses can acquire knowledge about how different cultural beliefs influence a client and their family members’ decision-making, approach to illness, pain, spirituality, grief, dying, death, and bereavement. See Table 17.2 for a brief comparison of various spiritual beliefs about death.[41],[42]

To learn more about holistic nursing care that addresses the spiritual needs of clients and their significant others, refer to the “Spirituality” chapter.

Table 17.2 Comparison of Spiritual Beliefs about Death[43]

| Religion | Beliefs Pertaining to Death | Preparation of the Body | Funeral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian

(Catholic and Protestant) |

Belief in Jesus Christ, the Bible, and an afterlife are central, although differences in interpretation exist in the various denominations. Catholics receive a sacrament called “anointing of the sick” when approaching the end of life. | Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. | Individuals are buried in cemeteries. Some denominations accept cremation as an alternative. Funerals or celebration of life services are typically held in a funeral home or church. |

| Jewish | Tradition cherishes life but death itself is not viewed as a tragedy. Views on an afterlife vary with the denomination (Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox). | Autopsy and embalming are forbidden under ordinary circumstances. Open caskets are not permitted. | Funeral is held as soon as possible after death. Dark clothing is worn at the funeral and after burial. It is forbidden to bury the deceased on the Sabbath or during festivals. Three mourning periods may be held after the burial, with Shiva being the first that occurs seven days after burial. |

| Buddhist | Both a religion and way of life with the goal of enlightenment. Life is believed to be a cycle of death and rebirth. | Goal is a peaceful death. Statue of Buddha may be placed at the bedside as the person is dying. Organ donation is not permitted. Incense is lit in the room following death. | Family washes and prepares the body after death. Cremation is preferred, but if buried, deceased are typically dressed in regular daily clothes instead of fancy clothing. Monks may be present at the funeral and lead the chanting. |

| Native American | Beliefs vary among tribes. Sickness is thought to mean that one is out of balance with nature. It is thought that ancestors can guide the deceased. Death is perceived as a journey to another world. Family may or may not be present for death. | Preparation of the body may be done by family. Organ donation is generally not preferred. | Various practices differ with tribes. Among the Navajo, hearing an owl or coyote is a sign of impending death, and the casket is left slightly open so the spirit can escape. Navajo and Apache tribes believe that spirits of the deceased can haunt the living. The Comanche tribe buries the dead in the place of death when possible or in a cave. |

| Hindu | Beliefs include reincarnation where a deceased person returns in the form of another, as well as Karma. | Organ donation and autopsy are acceptable. Death and dying must be peaceful. It is customary for the body to not be left alone until cremated. | Prefer cremation within 24 hours after death. Ashes are often scattered in sacred rivers. |

| Muslim | Believe in an afterlife and that the body must be quickly buried so that the soul may be freed. | Embalming and cremation are not permitted. Autopsy is permitted for legal or medical reasons only. After death, the body should face Mecca or the East. The body should be prepared by a person of the same gender. | Burial takes place as soon as possible. Women and men sit separately at the funeral. Flowers and excessive mourning are discouraged. The body is usually buried in a shroud and is buried with the head pointing toward Mecca. |

Read more about funeral traditions around the globe: Death is not the end: Fascinating funeral traditions from around the globe.

A Good Death

Death is a physical, psychological, social, and spiritual event. Family members who witness the last weeks, days, hours, and minutes of their loved one’s life will remember the death for all their lives. Although death is often perceived negatively in the American culture, research has found several themes that define a “good death” when nurses and the interdisciplinary team are caring for dying clients and their families:[44]

- Client preferences are met, including preferences for the dying process (i.e., where and with whom) and preparation for death (i.e., advanced directives, funeral arrangements).

- The client is pain-free with emotional well-being.

- The family is prepared for death and supportive of client’s preferences.

- Dignity and respect are demonstrated for the client.

- The client has a sense of life completion (i.e., saying goodbye and feeling life was well-lived).

- Spirituality and religious comfort are provided.

- Quality of life was maintained (i.e., maintaining hope, pleasure, gratitude).

- There is a feeling of trust/support/comfort from the nurse and interdisciplinary team.[45]

Nurses are often present during these final days and moments with clients during this difficult and sacred time.[46] Read more about nursing care performed during this time in the “Nursing Care During the Final Hours of Life” section.

Bereavement

The bereavement period includes grief (the inner feelings) and mourning (the outward reactions) after a loved one has died. A bereavement period is the time it takes for the mourner to feel the pain of the loss, mourn, grieve, and adjust to the world without the presence of the deceased. Bereavement can take a physical toll on a survivor. It is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy for survivors, and widows and widowers have an increased chance of dying after their spouses die.[47] See Figure 17.11[48] for an image depicting bereavement by family members.

A bereaved person should be encouraged to talk about the death and understand their feelings are normal. They should allow for sufficient time for expression of grief and should postpone significant decisions such as changing jobs or moving. It is also important to encourage them to focus on their spirituality to enhance coping during this difficult time.[49] See Figure 17.12[50] for an image a person depicting one type of spirituality.

Americans often deny the need to express grief or feel the pain that accompanies a loss. However, although painful, both are beneficial to healing. As part of the interdisciplinary health team, nurses are often at the front line of helping clients and family members cope with their feelings of loss and grief. The nursing role during the bereavement period includes the following[51]:

- Assisting with enhanced coping mechanisms

- Assessing and facilitating spirituality

- Facilitating the grieving process by supporting the client and survivors to feel the loss, express the loss, and move through the tasks of grief

- Communicating assessments and interventions with the interdisciplinary team

Children

Children who have experienced the loss of a parent, sibling, grandparent, or friend experience grief based on their developmental stage. It can be normal grief or complicated grief. Children may be limited in their ability to verbalize and describe their feelings and grief. See Figure 17.13[52] for an image of a child depicting grief.

Symptoms of grief in younger children include nervousness, uncontrollable rages, frequent illness, incontinence, rebellious behavior, hyperactivity, nightmares, depression, compulsive behavior, memories fading in and out, excessive anger, overdependence on the remaining parent, denial, and/or disguised anger. Children may not understand that death is permanent until they are in preschool or older. It is important to use the word “death” and not euphemisms like “gone to sleep” or “gone away,” which can be confusing or ambiguous to children. Additionally, using these euphemisms may cause children to fear sleep.[53]

Symptoms of grief in older children include difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, decreased academic performance, insomnia or sleeping too much, compulsiveness, social withdrawal, antisocial behavior, resentment of authority, overdependence, regression, resistance to discipline, suicidal thoughts or actions, nightmares, symbolic dreams, frequent sickness, accident proneness, overeating or undereating, truancy, experimentation with alcohol or drugs, depression, secretiveness, sexual promiscuity, or running away from home.[54]

Play is the universal language of children, so nurses should use it therapeutically when possible. Encouraging children that their grief is “normal” gives them comfort. Refer children, parents, and families to grief specialists as indicated. Make sure families are aware of local support groups.[55]

Parents and Grandparents

For parents, the death of a child can be devastating with a great need for bereavement support. For grandparents, the grief can be twofold as they experience their own grief, in addition to witnessing the grief of their child (the parent). Studies have shown that grandparents’ grief is seldom acknowledged.[56] See Figure 17.14[57] for an image of a sculpture depicting mourning for a child.

For more information on support for parents experiencing infant loss, go to http://nationalshare.org/

Spouses

The death of a husband or wife is well recognized as an emotionally devastating event, being ranked on life event scales as the most stressful of all possible losses. The intensity and persistence of the pain associated with this type of bereavement is thought to be due to the emotional marital bonds linking husbands and wives to each other. Spouses are co-managers of home and family, companions, sexual partners, and fellow members of larger social units.

Therapeutic Communication Tips

When communicating with the bereaved, it is more important to listen and be present rather than say the “right words.” It is also helpful to simply encourage silence. However, certain phrases should be avoided because they can create barriers in therapeutic communication:

- Avoid statements like, “I know/can imagine/understand how you feel.” Even if you have been through a similar situation, you don’t know how the survivor feels. Instead say, “This must be very difficult for you. Would you like to talk about it?”

- Don’t minimize the individual’s grief reaction with a statement like, “You should be over this by now.” Instead, say, “This process takes time, so don’t feel as if you need to rush through it.”

- Avoid statements that minimize the significance of the loss, such as, “At least you had a good life with them,” or “They’re in a better place now.” Instead, focus on exploring their feelings related to the loss, such as, “Tell me what your relationship was like.”[58]

Completion of the Grieving Process

Grief work is never completely finished because there will always be times when a memory, object, song, or anniversary of the death will cause feelings of loss for the survivor. However, healing occurs and is characterized by the following:

- The pain of the loss is lessened.

- The survivor has adapted to life without the deceased.

- The survivor has physically, psychologically, and socially “let go.”[59]

Letting go is a difficult process. One can let go and still find love and true meaning in the relationship they had with their loved one. Letting go does not mean cutting oneself off from the memories, but adapting to the loss and the continued bonds with the deceased.[60] See Figure 17.15[61] for a depiction of letting go by lighting a candle in memory of the deceased.

Self-Care

It is important for nurses to recognize that providing end-of-life care can have a significant impact on them. A nurse’s grief might be exacerbated when client loss is unexpected or is the result of a traumatic experience. For example, an emergency room nurse who provides care for a child who died as a result of a motor vehicle accident may find it difficult to cope with the loss and resume their normal work duties.

Grief can also be compounded when loss occurs repeatedly in one’s work setting or after providing care for a client for a long period of time. In some health care settings, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses do not have time to resolve grief from a loss before another loss occurs. Compassion fatigue and burnout occur frequently with nurses and other health care professionals who experience cumulative losses that are not addressed therapeutically.

Compassion fatigue is a state of chronic and continuous self-sacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that affect a health care professional’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. This can lead to a person being unable to care for or empathize with someone’s suffering. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation. It can be triggered by workplace demands, lack of resources to do work professionally and safely, interpersonal relationship stressors, or work policies that can lead to diminished caring and cynicism.[62] See Figure 17.16[63] for an image depicting a nurse at home experiencing burnout due to exposure to multiple competing demands of work, school, and family responsibilities.

Self-care is important to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. It is important for nurses to recognize the need to take time off, seek out individual healthy coping mechanisms, or voice concerns within their workplace. Prayer, meditation, exercise, art, and music are examples of healthy coping mechanisms that nurses can use to progress through their individual grief experience. Additionally, many organizations sponsor employee assistance programs that provide counseling services. These programs can be of great value and benefit in allowing individuals to voice their individual challenges with client loss. In times of traumatic client loss, many organizations hold debriefing sessions to allow individuals who participated in the care to come together to verbalize their feelings. These sessions are often held with the support of chaplains to facilitate individual coping and verbalization of feelings. (Read more about the role of chaplains in the “Spirituality” chapter.)

Throughout your nursing career, there will be times to stop and pay attention to warning signs of compassion fatigue and burnout. Here are some questions to consider:

- Has my behavior changed?

- Do I communicate differently with others?

- What destructive habits tempt me?

- Do I project my inner pain onto others?[64]

By becoming self-aware, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection prevents you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.[65]

In addition to self-care strategies, it is helpful for nurses to obtain additional education in end-of-life care. See the following for more information about obtaining a palliative care certificate for your portfolio.

Read more about online end-of-life curriculum available on the American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s End-of-Life-Care Curriculum web page.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Grief_and_loss_(16755561105).jpg” by Thomas8047 is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. The Macmillan Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “WWStoryRome.jpg” by Carptrash is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Shear, M. K. (2012). Grief and mourning gone awry: Pathway and course of complicated grief. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 119-28. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/mshear. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Kubler-ross-grief-cycle-1-728.jpg” by U3173699 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Oates & Maani and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Movieclips. (2014, February 5). Steel Magnolias (8/8) movie CLIP - I wanna know why (1989) HD [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/iZx1W6cHw-g ↵

- “Young-indian-with-disgusting-expression-showing-denial-with-hands-42509-pixahive.jpg” by Sukhjinder is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Child%27s_Angry_Face.jpg” by Babyaimeesmom is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Depressed_(4649749639).jpg” by Sander van der Wel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- “Contentment_at_its_best.jpg” by Neha Bhamburdekar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- World Health Organization. (2020). Palliative care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care ↵

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. (2021). Explanation of palliative care. https://www.nhpco.org/palliative-care-overview/explanation-of-palliative-care/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “hospice-1761276_1280.jpg” by truthseeker08 is licensed under CC0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2017, May 17). What are palliative care and hospice care? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2021. Do-not-resuscitate order; [updated 2021, June 9].https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000473.htm ↵

- Ouellette, L., Puro, A., Weatherhead, J., Shaheen, M., Chassee, T., Whalen, D., & Jones, J.. (2018). Public knowledge and perceptions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR): Results of a multicenter survey. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 36(10), 1900-1901. https://doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.103. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “140305-M-KL110-002_(13063045524).jpg” by U.S. Department of Defense Current Photos is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). End-of-life-care (ELNEC). https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC ↵

- “Mourning_in_Shanghai_(1).jpg” by Medalofdead is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Pasero, C., & MacCaffery, M. (2010). Pain assessment and pharmacological management (1st ed.). Mosby. ↵

- Pasero, C., & MacCaffery, M. (2010). Pain assessment and pharmacological management (1st ed.). Mosby. ↵

- Karnes, B. (2009). Gone from my sight: The dying experience. Barbara Karnes Books. ↵

- Karnes, B. (2009). Gone from my sight: The dying experience. Barbara Karnes Books. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Mourning,_Lette_Valeska.jpg” by Lette Valeska is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “meditation-1350599_960_720.jpg” by brenkee is licensed under CC0. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “sad-72217_960_720.jpg” by PublicDomainPictures is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Sarcophagus,_marble,_mourning_for_child,_100-200_AD,_AM_Agrigento,_121062.jpg” by Zde is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Candle_burning.jpg” by NCCo at English Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Burnout_At_Work_-_Occupational_Burnout.jpg” by Microbiz Mag is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

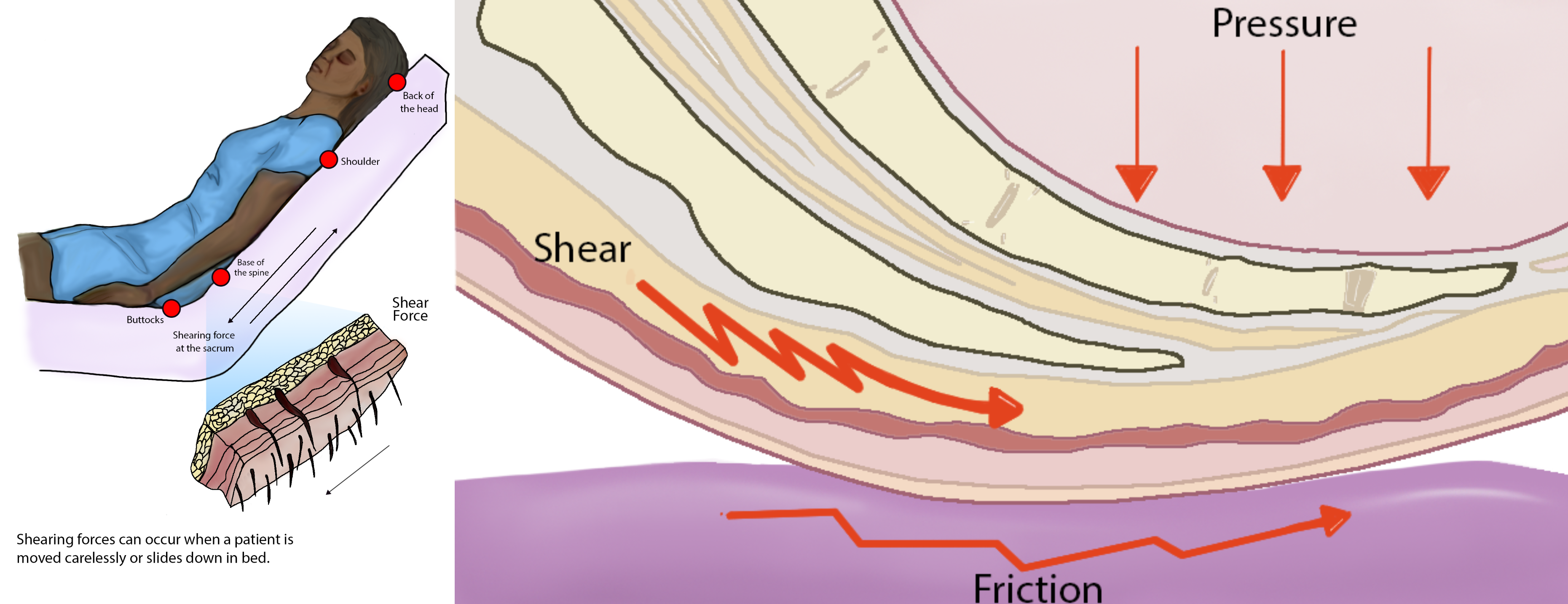

The remainder of this chapter will focus on applying the nursing process to a specific type of wound called a pressure injury. Pressure injuries are defined as, “Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.” (Note that the 2016 NPUAP Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of the historic term “pressure ulcer” because a pressure injury can occur without an ulcer present.) Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischia, and coccyx and form when the skin layer of tissue gets caught between an external hard surface, such as a bed or chair, and the internal hard surface of a bone.

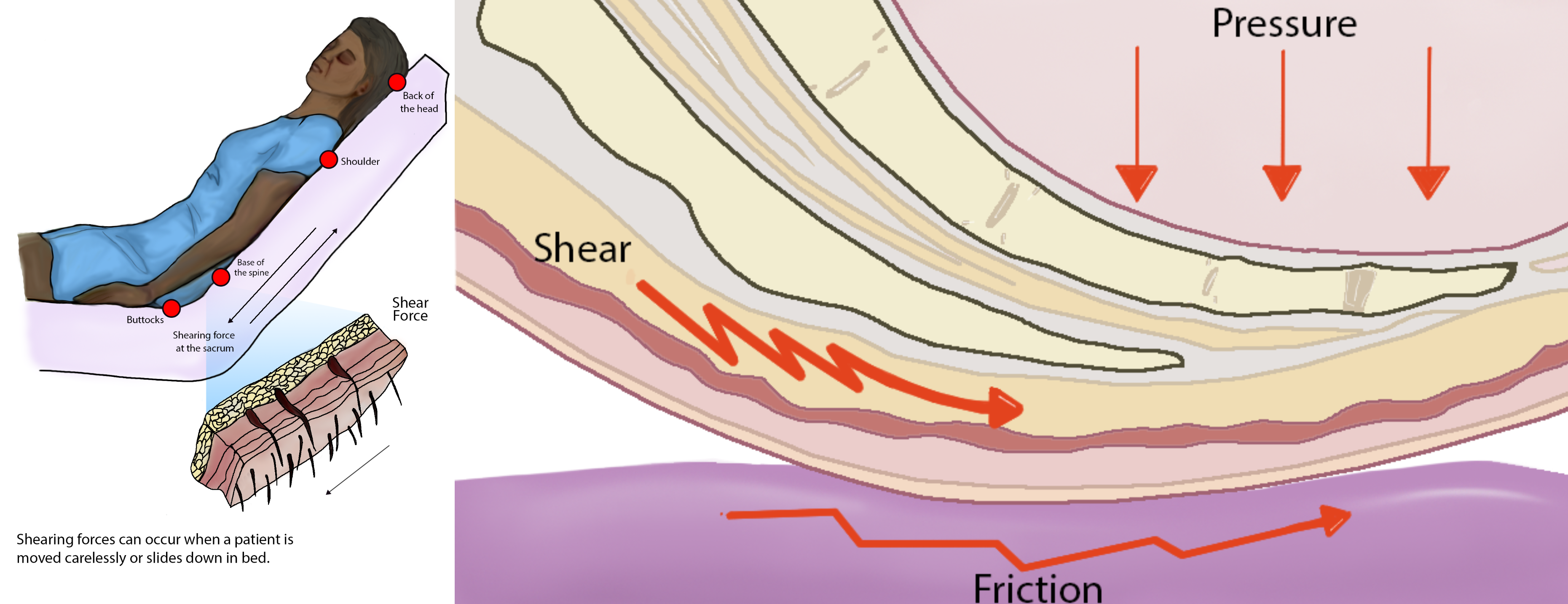

Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a client slides down in bed, the outer layer of skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction. However, the deeper layer of tissue (attached to bone) moves as the client slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then causes decreased blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues resulting in a pressure injury.[1]

Friction refers to rubbing the skin against a hard object, such as the bed or the arm of a wheelchair. This rubbing causes heat, which can remove the top layer of skin and often results in skin damage. See Figure 10.13[2] for an illustration of shear and friction forces in the development of pressure injuries.

Hospital-acquired or worsening pressure injuries during hospitalization are considered "never events," meaning they are a serious, preventable medical errors that should never occur and require reporting to The Joint Commission. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and many private insurers will no longer pay for additional costs associated with "never events."[3],[4] Pressure injuries can be prevented with diligent assessment and nursing interventions such as frequent repositioning and providing good skin care.

Staging

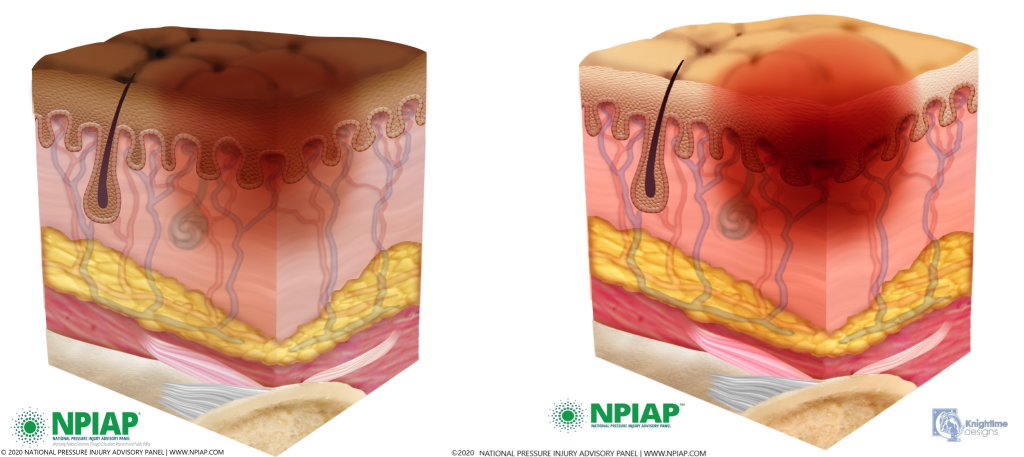

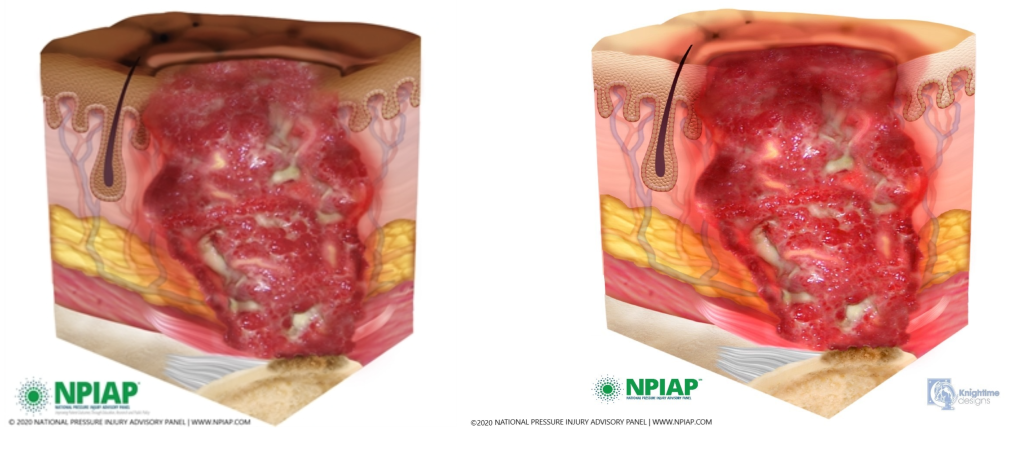

When assessed, pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have the least amount of tissue damage as evidenced by reddened, intact skin, whereas Stage 4 pressure injuries have the greatest amount of damage with deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue, muscle, ligaments, or tendons. See Figure 10.14[5] for images of four stages of pressure injuries.[6] Each stage is further described in the following subsections.

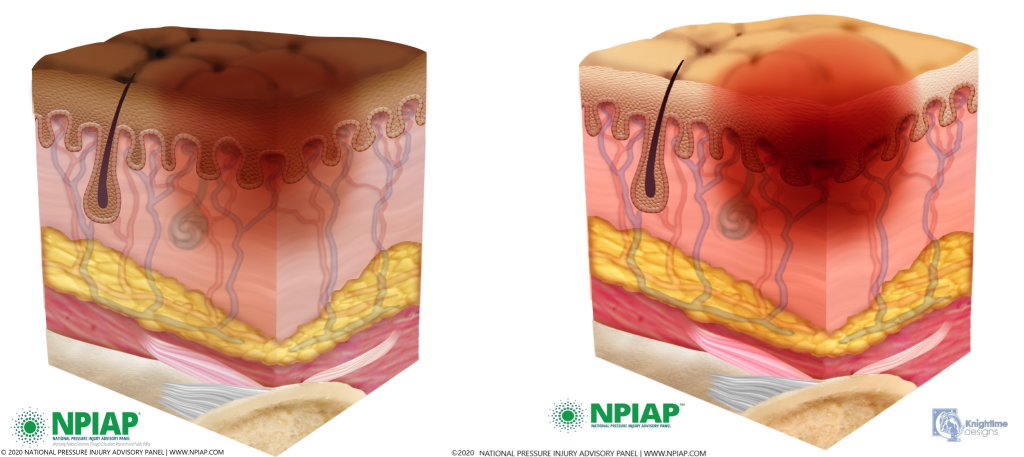

Stage 1 Pressure Injuries

Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe an area of reddened skin that does not turn white when pressed. Nonblanchable erythema is an early sign of damage to underlying tissue caused by poor blood flow, ischemia, and damage to blood vessels in the area. Because damage is already present, there is a greater risk for Stage 1 pressure injuries to develop into worse pressure injuries if interventions to relieve pressure and not implemented. Skin with dark pigmentation may not demonstrate visible blanching, so it can be challenging to detect Stage 1 pressure injuries. For clients with dark pigmentation, nurses should assess for pain, firmness, softness, changes in temperature, or changes in color compared to surrounding areas.[7],[8]

See Figure 10.15[9] for an illustration of a Stage 1 pressure injury.

Stage 2 Pressure Injuries

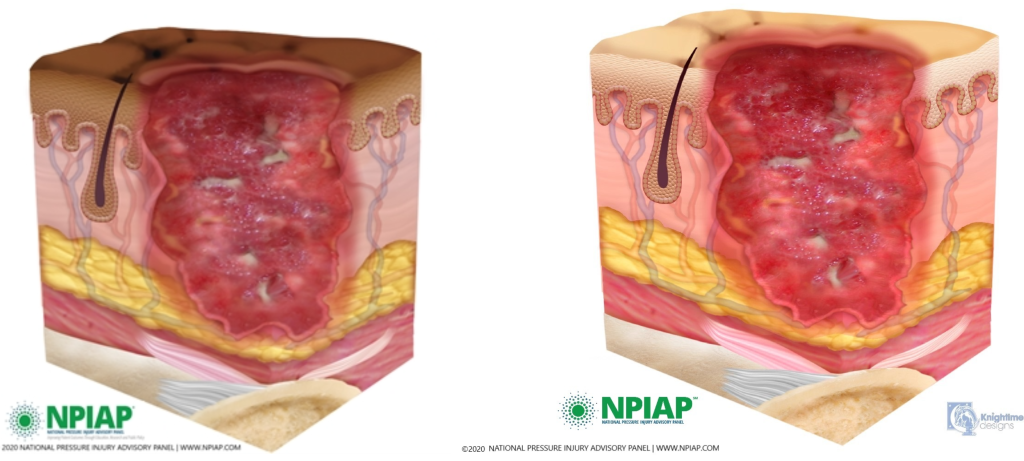

Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound has completely broken through the top layer of skin, and partly through the second layer, resulting in a shallow wound. The wound is shallow and generally open. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister.[10] The wound area may be painful and the surrounding tissue may be swollen or discolored.[11] See Figure 10.16[12] for an illustration of a Stage 2 pressure injury.

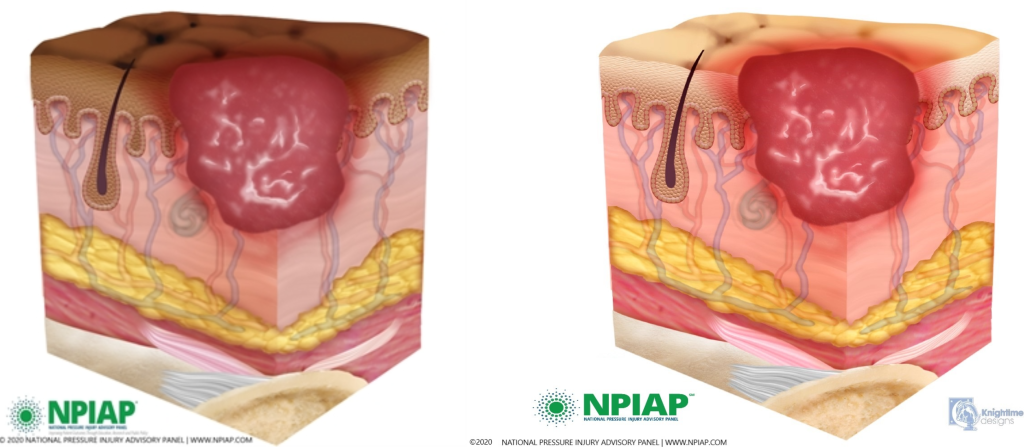

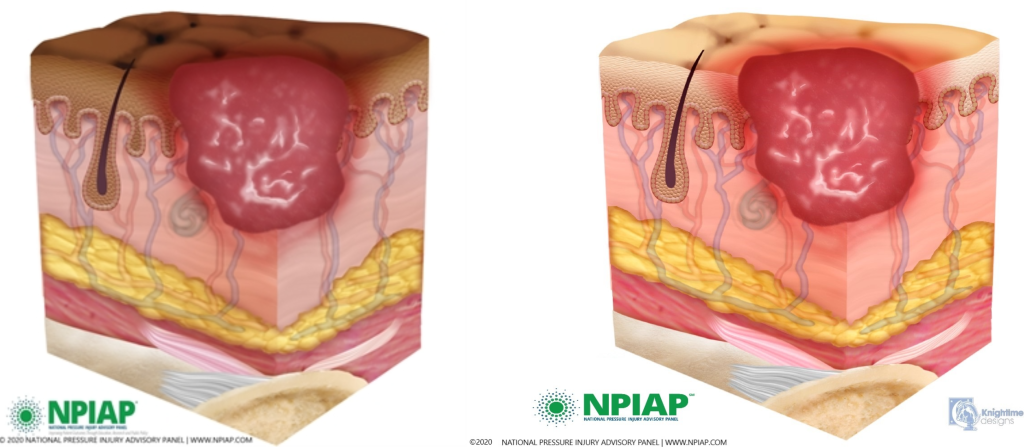

Stage 3 Pressure Injuries

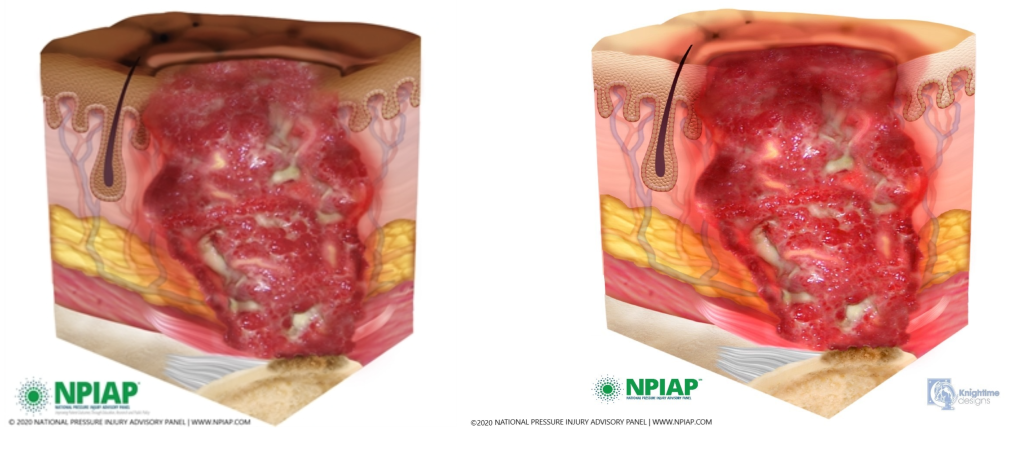

Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Because the wound extends through all skin layers, there is increased risk of infection in Stage 3 pressure injuries. There may be pus draining from the wound, tissue necrosis, pain, or fever, especially in the presence of an infection.[13] See Figure 10.17[14] for an illustration of a Stage 3 pressure injury.

Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edge becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the skin surface that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns.

Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[15] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for accurate wound staging and for healing to occur. Removed of slough or eschar is surgically performed by specially trained health care providers. Nurses may apply prescribed chemical debridement agents or wet-to-dry dressings for mechanical debridement per provider orders.

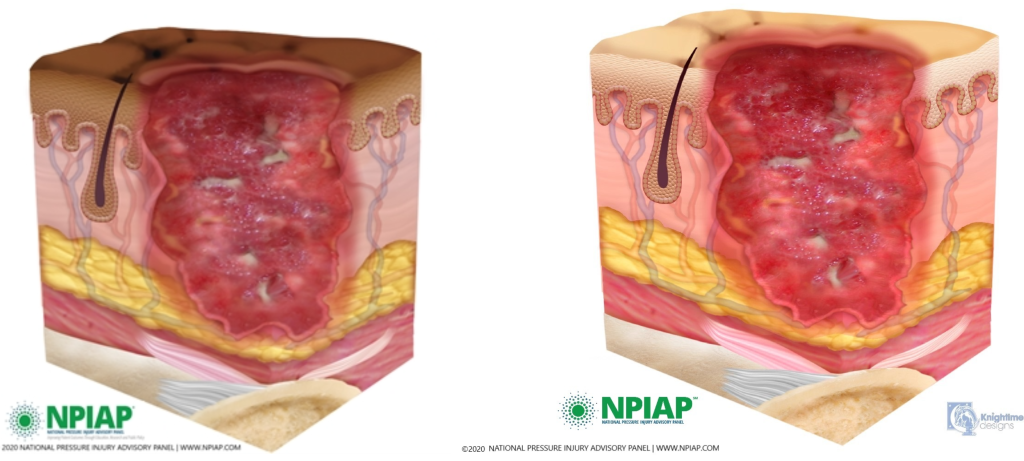

Stage 4 Pressure Injuries

Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss, like in Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Stage 4 pressure injuries are at an increased risk of infection because their depth goes through all skin layers. There may be pain associated with Stage 4 pressure ulcers, although they are often less painful because the wound damages nerve endings. There also at be firm or mushy texture at the site, discoloration, or necrosis to the wound. Because the wound often extends to the bone, thus exposing the bone to infectious agents in the environment, osteomyelitis (bone infection) may also be present. Osteomyelitis is a serious bone infection that may require amputation or cause death if not promptly treated aggressively with antibiotics.[16],[17]

See Figure 10.18[18] for an illustration of a Stage 4 pressure injury.

View images of different stages of pressure injuries on people with dark skin tones on the PPPIA Pressure Ulcers in People With Dark Skin Tones poster.

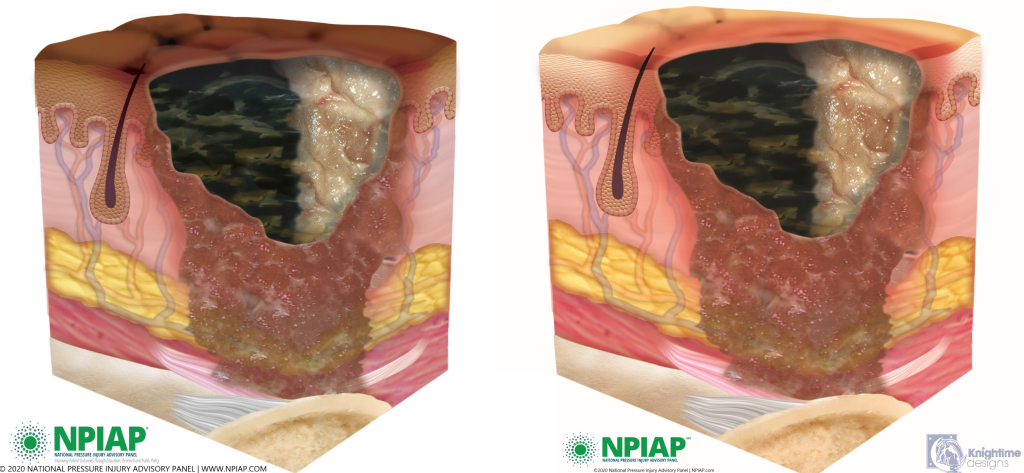

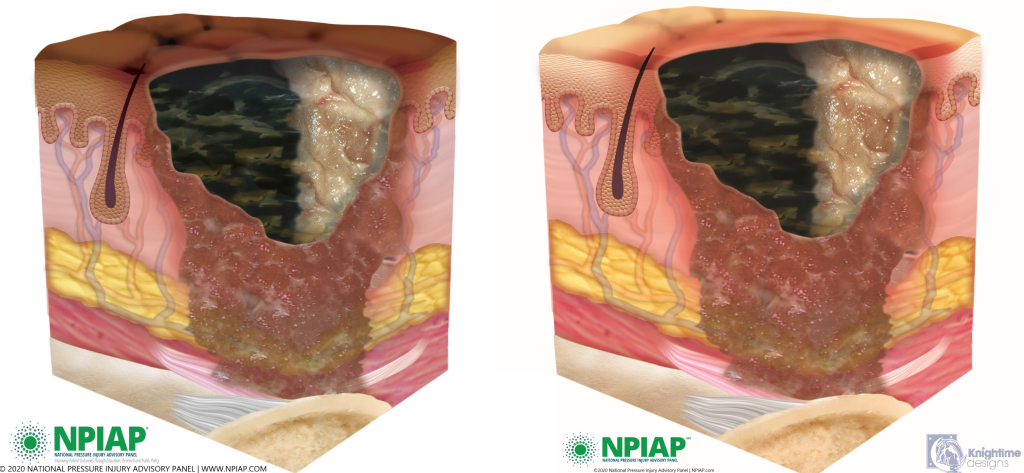

Unstageable Pressure Injuries

Unstageable pressure injuries are full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which the extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If slough or eschar were to be removed, a Stage 3 or Stage 4 pressure injury would likely be revealed. However, dry and adherent eschar on the heel or ischemic limb is not typically removed.[19] See Figure 10.19[20] for an illustration of an unstageable pressure ulcer due to the presence of eschar (on the left side of the wound) and slough (on the right side of the wound).

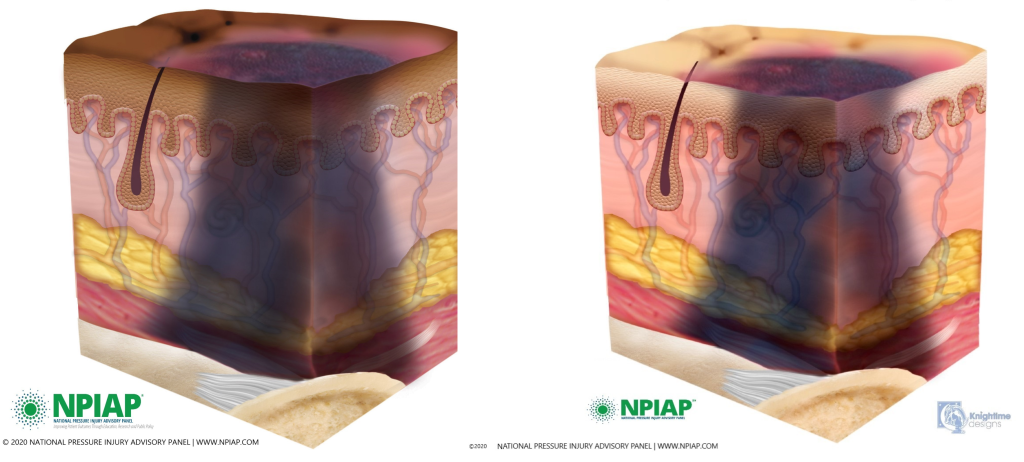

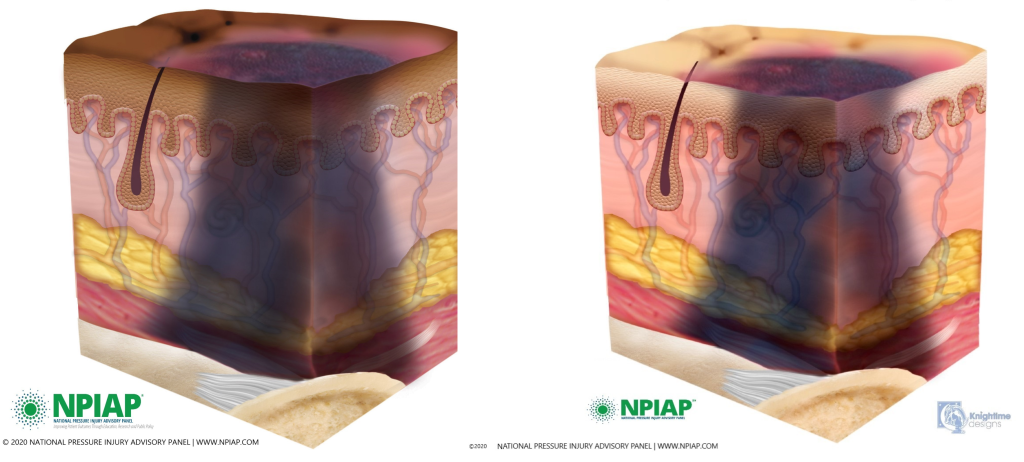

Deep Tissue Pressure Injuries

Deep tissue pressure injuries consist of persistent nonblanchable and deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration of an area. These discolorations typically reveal a dark wound bed or blood-filled blister. Be aware that the discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Deep tissue injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure, as well as shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or it may resolve without tissue loss.[21],[22] See Figure 10.20 for an illustration of a deep tissue injury.

Video Review of Assessing Pressure Injuries[23]

The remainder of this chapter will focus on applying the nursing process to a specific type of wound called a pressure injury. Pressure injuries are defined as, “Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.” (Note that the 2016 NPUAP Pressure Injury Staging System now uses the term “pressure injury” instead of the historic term “pressure ulcer” because a pressure injury can occur without an ulcer present.) Pressure injuries commonly occur on the sacrum, heels, ischia, and coccyx and form when the skin layer of tissue gets caught between an external hard surface, such as a bed or chair, and the internal hard surface of a bone.

Shear occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue. For example, when a client slides down in bed, the outer layer of skin remains immobile because it remains attached to the sheets due to friction. However, the deeper layer of tissue (attached to bone) moves as the client slides down. This opposing movement of the outer layer of skin and the underlying tissues causes the capillaries to stretch and tear, which then causes decreased blood flow and oxygenation of the surrounding tissues resulting in a pressure injury.[24]

Friction refers to rubbing the skin against a hard object, such as the bed or the arm of a wheelchair. This rubbing causes heat, which can remove the top layer of skin and often results in skin damage. See Figure 10.13[25] for an illustration of shear and friction forces in the development of pressure injuries.

Hospital-acquired or worsening pressure injuries during hospitalization are considered "never events," meaning they are a serious, preventable medical errors that should never occur and require reporting to The Joint Commission. Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and many private insurers will no longer pay for additional costs associated with "never events."[26],[27] Pressure injuries can be prevented with diligent assessment and nursing interventions such as frequent repositioning and providing good skin care.

Staging

When assessed, pressure injuries are staged from 1 through 4 based on the extent of tissue damage. For example, Stage 1 pressure injuries have the least amount of tissue damage as evidenced by reddened, intact skin, whereas Stage 4 pressure injuries have the greatest amount of damage with deep, open ulcers affecting underlying tissue, muscle, ligaments, or tendons. See Figure 10.14[28] for images of four stages of pressure injuries.[29] Each stage is further described in the following subsections.

Stage 1 Pressure Injuries

Stage 1 pressure injuries are intact skin with a localized area of nonblanchable erythema where prolonged pressure has occurred. Nonblanchable erythema is a medical term used to describe an area of reddened skin that does not turn white when pressed. Nonblanchable erythema is an early sign of damage to underlying tissue caused by poor blood flow, ischemia, and damage to blood vessels in the area. Because damage is already present, there is a greater risk for Stage 1 pressure injuries to develop into worse pressure injuries if interventions to relieve pressure and not implemented. Skin with dark pigmentation may not demonstrate visible blanching, so it can be challenging to detect Stage 1 pressure injuries. For clients with dark pigmentation, nurses should assess for pain, firmness, softness, changes in temperature, or changes in color compared to surrounding areas.[30],[31]

See Figure 10.15[32] for an illustration of a Stage 1 pressure injury.

Stage 2 Pressure Injuries

Stage 2 pressure injuries are partial-thickness loss of skin with exposed dermis. The wound has completely broken through the top layer of skin, and partly through the second layer, resulting in a shallow wound. The wound is shallow and generally open. The wound bed is viable and may appear like an intact or ruptured blister.[33] The wound area may be painful and the surrounding tissue may be swollen or discolored.[34] See Figure 10.16[35] for an illustration of a Stage 2 pressure injury.

Stage 3 Pressure Injuries

Stage 3 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss in which fat is visible, but cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, and bone are not exposed. The depth of tissue damage varies by anatomical location. Because the wound extends through all skin layers, there is increased risk of infection in Stage 3 pressure injuries. There may be pus draining from the wound, tissue necrosis, pain, or fever, especially in the presence of an infection.[36] See Figure 10.17[37] for an illustration of a Stage 3 pressure injury.

Undermining and tunneling may occur in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edge becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin. Tunneling refers to passageways underneath the skin surface that extend from a wound and can take twists and turns.

Slough and eschar may also be present in Stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries. Slough is inflammatory exudate that is usually light yellow, soft, and moist. Eschar is dark brown/black, dry, thick, and leathery dead tissue. If slough or eschar obscures the wound so that tissue loss cannot be assessed, the pressure injury is referred to as unstageable.[38] In most wounds, slough and eschar must be removed by debridement for accurate wound staging and for healing to occur. Removed of slough or eschar is surgically performed by specially trained health care providers. Nurses may apply prescribed chemical debridement agents or wet-to-dry dressings for mechanical debridement per provider orders.

Stage 4 Pressure Injuries

Stage 4 pressure injuries are full-thickness tissue loss, like in Stage 3 pressure injuries, but also have exposed cartilage, tendon, ligament, muscle, or bone. Stage 4 pressure injuries are at an increased risk of infection because their depth goes through all skin layers. There may be pain associated with Stage 4 pressure ulcers, although they are often less painful because the wound damages nerve endings. There also at be firm or mushy texture at the site, discoloration, or necrosis to the wound. Because the wound often extends to the bone, thus exposing the bone to infectious agents in the environment, osteomyelitis (bone infection) may also be present. Osteomyelitis is a serious bone infection that may require amputation or cause death if not promptly treated aggressively with antibiotics.[39],[40]

See Figure 10.18[41] for an illustration of a Stage 4 pressure injury.

View images of different stages of pressure injuries on people with dark skin tones on the PPPIA Pressure Ulcers in People With Dark Skin Tones poster.

Unstageable Pressure Injuries

Unstageable pressure injuries are full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which the extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar. If slough or eschar were to be removed, a Stage 3 or Stage 4 pressure injury would likely be revealed. However, dry and adherent eschar on the heel or ischemic limb is not typically removed.[42] See Figure 10.19[43] for an illustration of an unstageable pressure ulcer due to the presence of eschar (on the left side of the wound) and slough (on the right side of the wound).

Deep Tissue Pressure Injuries

Deep tissue pressure injuries consist of persistent nonblanchable and deep red, maroon, or purple discoloration of an area. These discolorations typically reveal a dark wound bed or blood-filled blister. Be aware that the discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. Deep tissue injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure, as well as shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury, or it may resolve without tissue loss.[44],[45] See Figure 10.20 for an illustration of a deep tissue injury.

Video Review of Assessing Pressure Injuries[46]

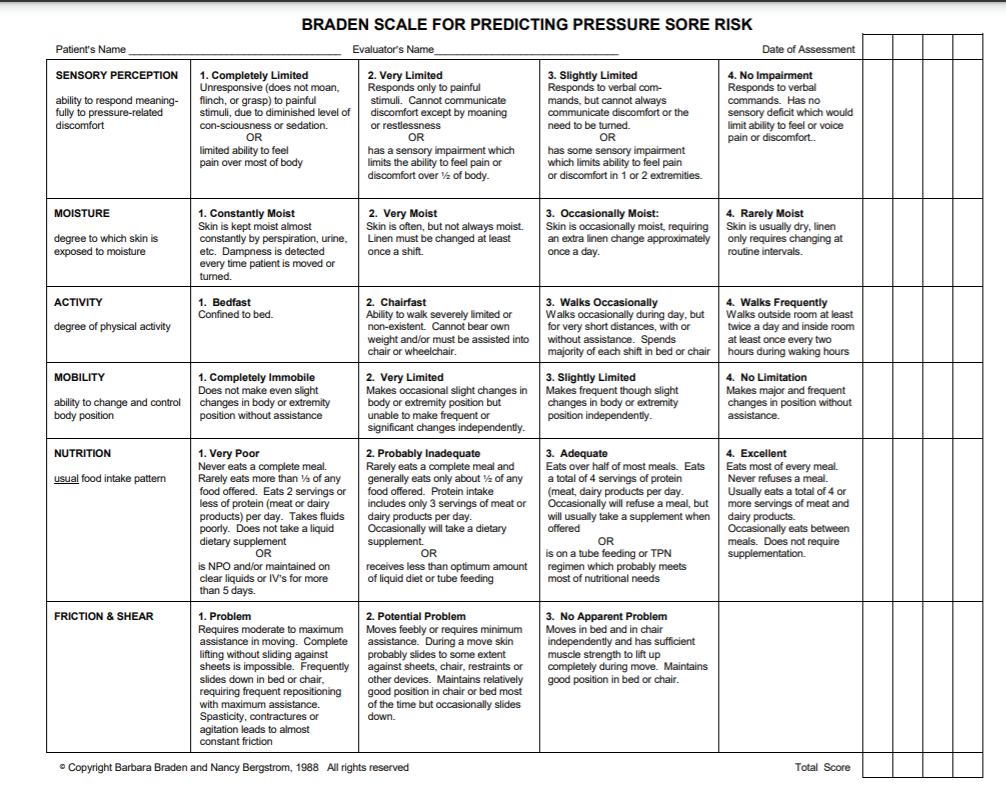

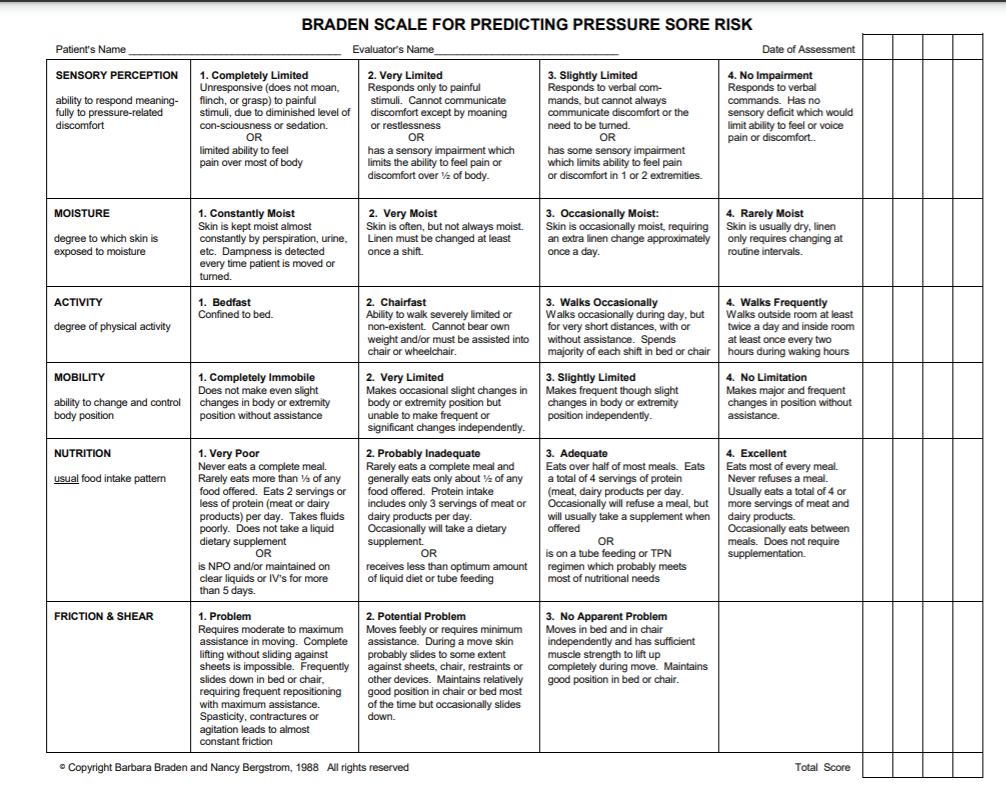

Several factors place a client at risk for developing a pressure injury, in addition to shear and friction. These factors include decreased sensory perception, increased moisture, decreased activity, impaired mobility, and inadequate nutrition. The Braden Scale is a standardized, evidence-based assessment tool commonly used in health care to assess and document a client’s risk for developing pressure injuries. See Figure 10.21[47] for an image of a Braden Scale. Risk factors are rated on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 being “completely limited” and 4 being “no impairment.” The scores from the six categories are added, and the total score indicates a client’s risk for developing a pressure injury based on these ranges:

- Mild risk: 15-18

- Moderate risk: 13-14

- High risk: 10-12

- Severe risk: less than 9

How to Score the Braden Scale

Each risk factor on the Braden Scale is rated from 1 to 4 based on the client’s assessment findings. When using the Braden Scale, start with the first category and review each description listed across the row for each of the ratings from 1 to 4, and choose the one that best describes the client’s current status. Continue this process for all rows. Add all six numbers to determine a total score, and then use the total score to determine if the client is at mild, moderate, high, or severe risk for developing a pressure injury. The lower the score, the higher the risk of developing a pressure injury. Additionally, customized nursing interventions are implemented based on the rating in each category. The lower the score, the more aggressive actions are taken to prevent or heal a pressure injury. Descriptions of the ratings from 1-4 for each risk factor, along with targeted interventions for each rating, are further described in the following subsections.

Sensory Perception

The sensory perception risk factor is defined as the ability to respond meaningfully to pressure-related discomfort. If a client is unable to feel pressure-related discomfort and respond to it appropriately by moving or reporting pain, they are at high risk of developing a pressure injury. This risk category describes two different issues that affect sensory perception. The first description refers to the client’s level of consciousness, and the second description refers to the client’s ability to feel cutaneous sensation. See Table 10.5a for a description of each level of risk from 1-4 with associated interventions for each level.[48]

Table 10.5a Descriptions and Interventions by Level of Risk for Sensory Perception

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory Perception | 4--No Impairment

Responds to verbal commands. Has no sensory deficit that would limit ability to feel or voice pain or discomfort. |

|

| Sensory Perception | 3--Slightly Limited

Responds to verbal commands but cannot always communicate discomfort or the need to be turned. OR Has some sensory impairment that limits ability to feel pain or discomfort in 1 or 2 extremities. |

|

| Sensory Perception | 2--Very Limited

Responds only to painful stimuli. Cannot communicate discomfort except by moaning or restlessness. OR Has a sensory impairment that limits the ability to feel pain or discomfort over half of the body. |

All interventions mentioned in 3--Slightly Limited plus:

|

| Sensory Perception | 1--Completely Limited

Unresponsive (does not moan, flinch, or grasp) to painful stimuli, due to diminished level of consciousness or sedation. OR Limited ability to feel pain over most of the body. |

All interventions mentioned in 2--Very Limited plus:

|

Moisture

The moisture risk factor is defined as the degree to which skin is exposed to moisture. Prolonged exposure to moisture increases the probability of skin breakdown. Moisture can come from several sources, such as perspiration, urine incontinence, stool incontinence, or wound drainage. Frequent surveillance, removal of wet or soiled linens, and use of protective skin barriers greatly reduce this risk factor. See Table 10.5b for specific interventions for each level of risk.[49]

Table 10.5b Interventions by Level of Risk for Moisture

| Rating Description | Interventions | |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture

|

4--Rarely Moist

Skin is usually dry; linen only requires changing at routine intervals. |

|

| Moisture

|

3--Occasionally Moist

Skin is occasionally moist, requiring an extra linen change approximately once per day. |

All interventions mentioned in 4--Rarely Moist plus:

|

| Moisture

|

2--Often Moist

Skin is often but not always moist. Linen must be changed at least once per shift. |

All interventions mentioned in 3--Occasionally Moist plus:

|

| Moisture

|

1--Constantly Moist

Skin is kept moist almost constantly by perspiration, urine, etc. Dampness is detected every time the client is moved or turned. |

All interventions mentioned in 2--Often Moist plus:

|

Activity

The activity risk factor is defined as the degree of physical activity. For example, walking or moving from a bed to a chair reduces a client’s risk of developing a pressure injury by redistributing pressure points and increasing blood and oxygen flow to areas at risk.

Level of activity is defined by how frequently the client is able to get out of bed, move into a chair, or ambulate with or without help. See Table 10.5c for a description of each level of risk from 1-4 with associated interventions for each.[50]

Table 10.5c Descriptions and Interventions by Level of Risk for Activity[51]

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Activity

|

4--Walks Frequently

Walks outside the room at least twice a day and inside the room at least once every two hours during waking hours. |

|

| Activity

|

3--Walks Occasionally

Walks occasionally during the day, but for very short distances, with or without assistance. Spends the majority of each shift in bed or chair. |

|

| Activity

|

2--Chair Fast

Ability to walk is severely limited or nonexistent. Cannot bear their own weight and/or must be assisted into chair or wheelchair. |

|

| Activity

|

1--Bedfast

Confined to bed. |

|

Mobility

The mobility risk factor is defined as the client’s ability to change or control their body position. For example, healthy people frequently change body position by rolling over in bed, shifting weight in a chair after sitting too long, or by moving their extremities. However, tissue damage will occur if a client is unable to reposition on their own power unless caregivers frequently change their position. See Table 10.5d for interventions for each level of risk from 1-4.[52]

Table 10.5d Interventions by Level of Risk for Mobility[53]

| Assessment Category | Rating Description | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility

|

4--No Limitations

Makes major and frequent changes in position without assistance. |

|

| Mobility

|

3--Slightly Limited

Makes frequent though slight changes in body or extremity position independently. |

|

| Mobility

|

2--Very Limited

Makes occasional slight changes in body or extremity position but unable to make frequent or significant changes independently. |

|

| Mobility

|

1-Completely Immobile

Does not make even slight changes in body or extremity position without assistance. |

Same interventions as for 2--Very Limited |

Nutrition