Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Gastrointestinal Function

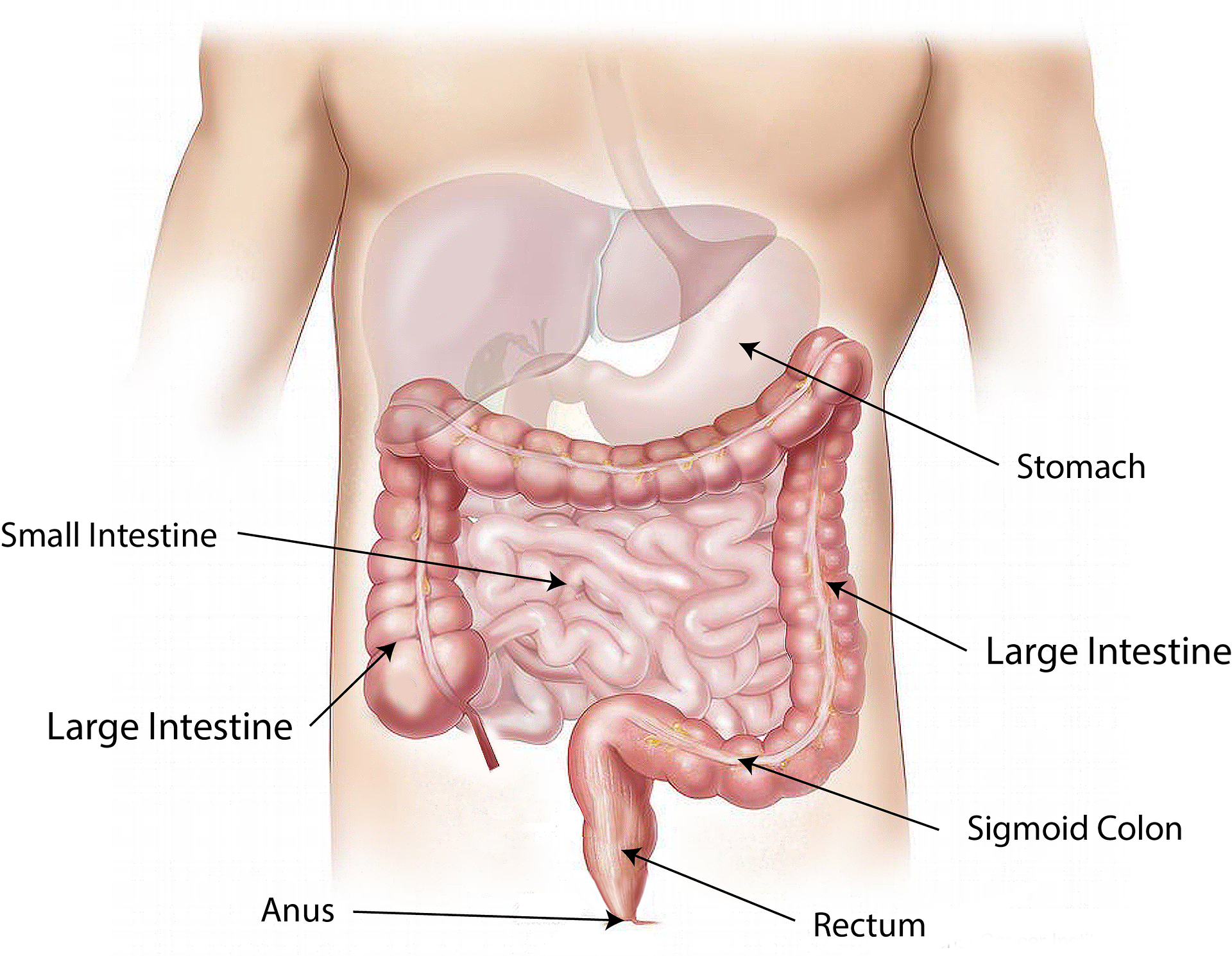

It is important to understand the anatomy and functioning of the gastrointestinal system before administering feedings or medications through an enteral tube. See Figure 17.1[1] for an illustration of the anatomy of the gastrointestinal system.

For more information about the digestive function of the gastrointestinal system, visit the “Gastrointestinal System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Enteral Nutrition

Enteral nutrition is indicated for patients who need nutritional supplementation and have a functioning gastrointestinal tract, but cannot swallow food safely. Feedings can be administered via enteral tubes placed into the stomach or into the small intestine (usually the jejunum). For example, enteral feeding is commonly used for patients with the following conditions:

- Impaired swallowing (such as from a stroke or Parkinson’s disease)

- Decreased level of consciousness

- Respiratory distress requiring mechanical ventilation

- Oropharyngeal or esophageal obstruction (such as in head or neck cancer)

- Hypercatabolic states (such as in severe burns)[2]

For short-term feeding, NG tubes are used. If the duration of feeding is longer than four weeks or if access through the nose is contraindicated, a surgery is performed to place the tube directly through the gastrointestinal wall (for example, PEG or PEJ tubes).

Patients who are not candidates for enteral nutrition are prescribed parenteral nutrition. Parenteral nutrition is a concentrated intravenous solution containing glucose, amino acids, minerals, electrolytes, and vitamins. A lipid solution is typically administered as a separate infusion. This combination of solutions is called total parenteral nutrition because it supplies complete nutritional support. Parenteral nutrition is administered via a large central intravenous line, typically the subclavian or internal jugular vein, because it is irritating to the blood vessels.

Types of Enteral Tubes

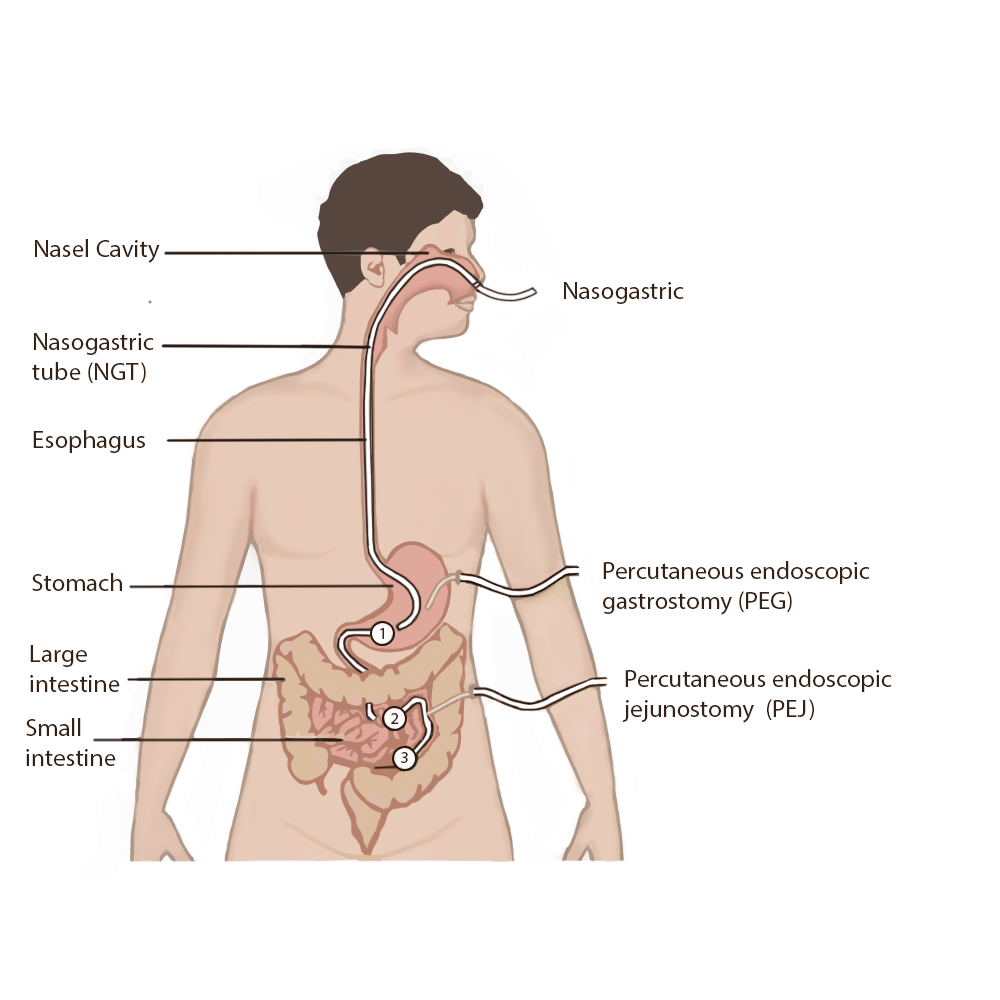

There are several different types of enteral tubes based on their location in the gastrointestinal system, as well as their function. Three commonly used enteral tubes are the nasogastric tube, the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, and the percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) tube. See Figure 17.2[3] for an illustration of common enteral tubes. NG tubes are typically used for a short period of time (less than four weeks), whereas PEG and PEJ tubes are inserted for long-term enteral nutrition. Some institutions also place nasoduodenal (ND) tubes to provide long-term enteral nutrition.[4]

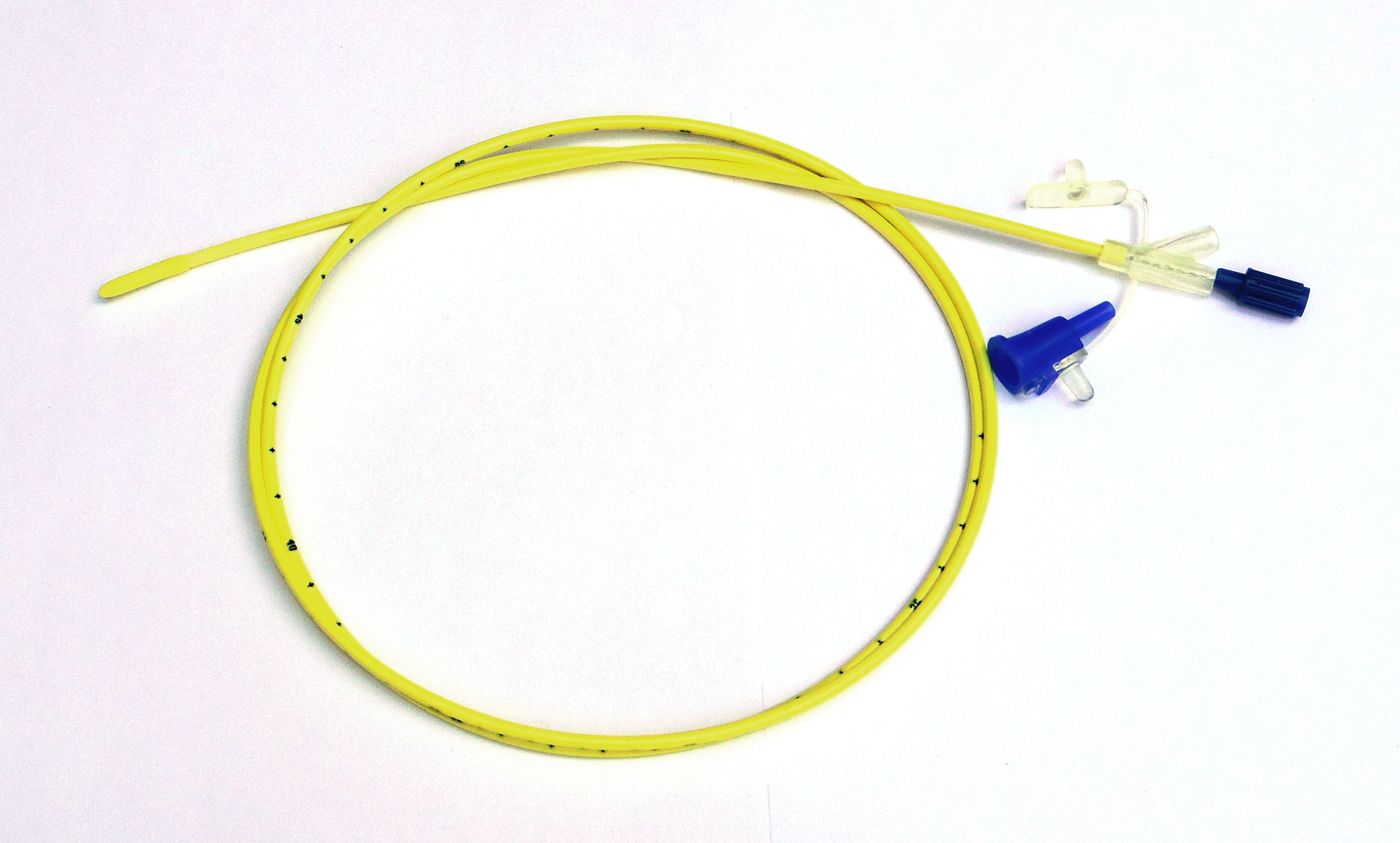

A nasogastric (NG) tube is a single- or double-lumen tube that is inserted into the nasopharynx through the esophagus and into the stomach. NG tubes can be used for feeding, medication administration, and suctioning. NG tubes used for feeding and medication administration are small and flexible, whereas NG tubes used for suctioning are larger and more rigid. NG tubes are secured externally on the patient’s nose or cheek by adhesive tape or a fixation device, so this area should be assessed daily for signs of pressure damage. See Figure 17.3[5] for an image of a small-bore feeding tube.

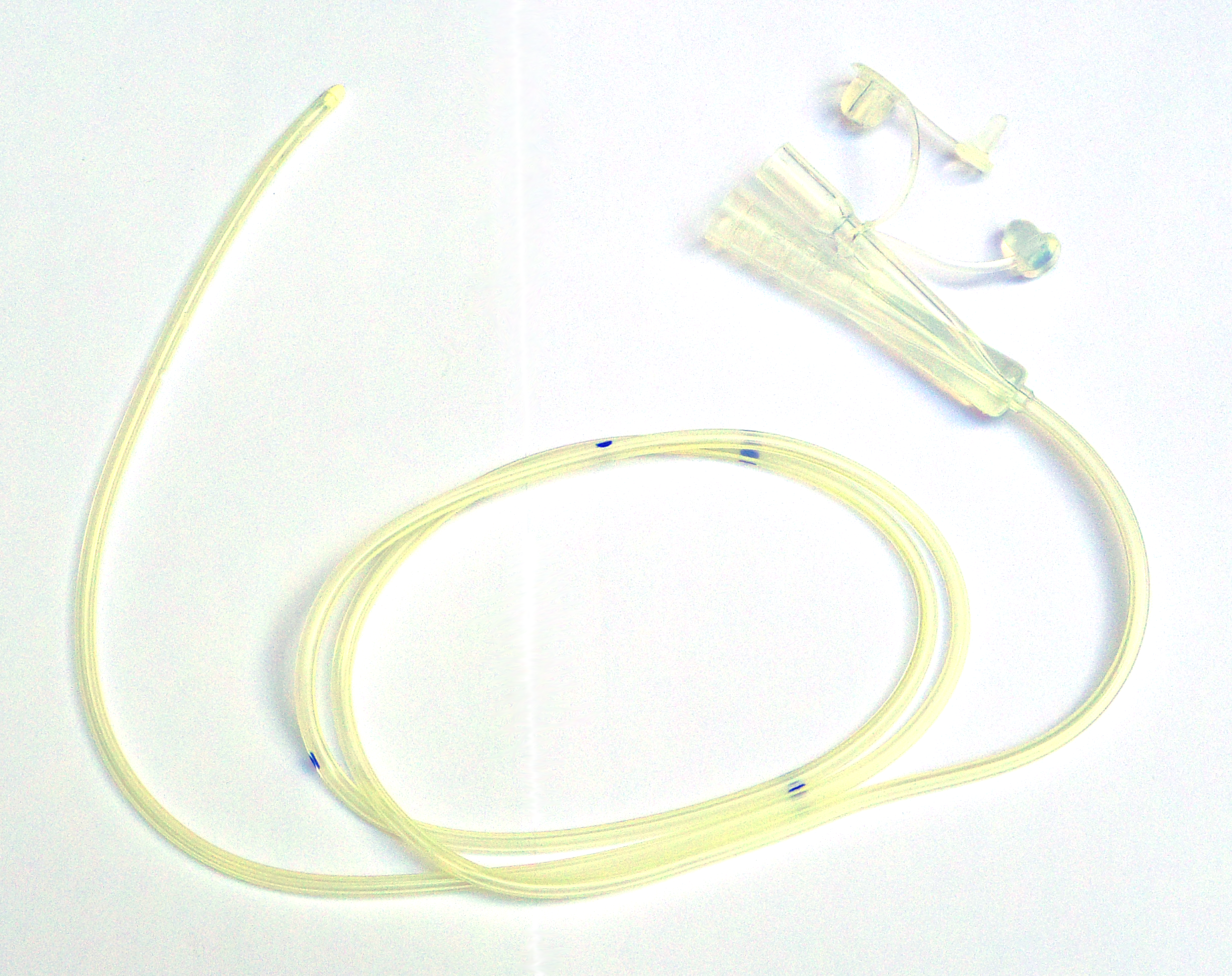

An example of a large-bore nasogastric tube is the Salem Sump. Large-bore nasogastric tubes, such as the Salem Sump, are used for gastric decompression. The Salem Sump has a double-lumen that includes a venting system. One lumen is used to empty the stomach, and the other lumen is used to provide a continuous flow of air. The continuous flow of air reduces negative pressure and prevents gastric mucosa from being drawn into the catheter, which causes mucosal damage. This terminal end also has an anti-reflux valve to prevent gastric secretions from traveling through the wrong lumen. See Figure 17.4[6] for an example of a double-lumen enteral tube.

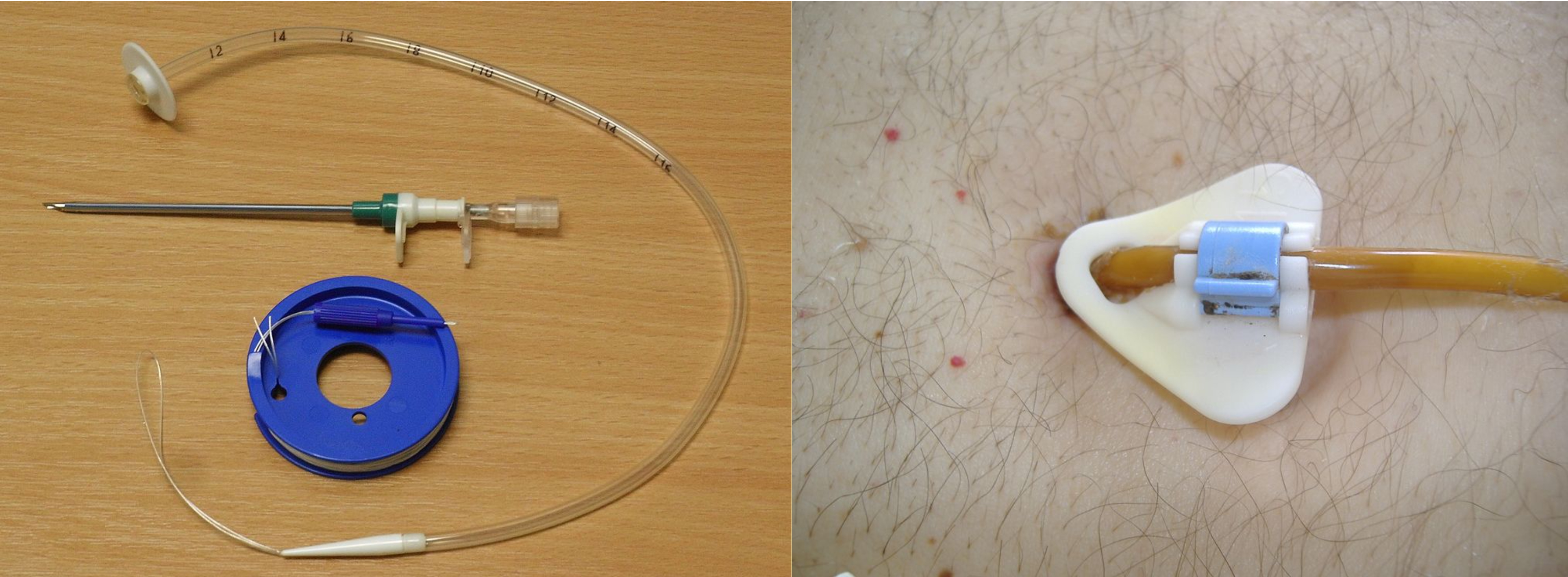

Other types of tubes are placed through the patient’s abdominal wall and are used for long-term enteral feeding. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is placed via an endoscopic procedure into the stomach. Alternatively, a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) tube is placed in the jejunum of the small intestine for patients who cannot tolerate the administration of enteral formula or medications into the stomach due to medical conditions such as delayed gastric emptying. See Figure 17.5[7] for an image of a PEG tube insertion kit and the appearance of an enteral tube as it exits from a patient’s abdomen.

Assessing Tube Placement

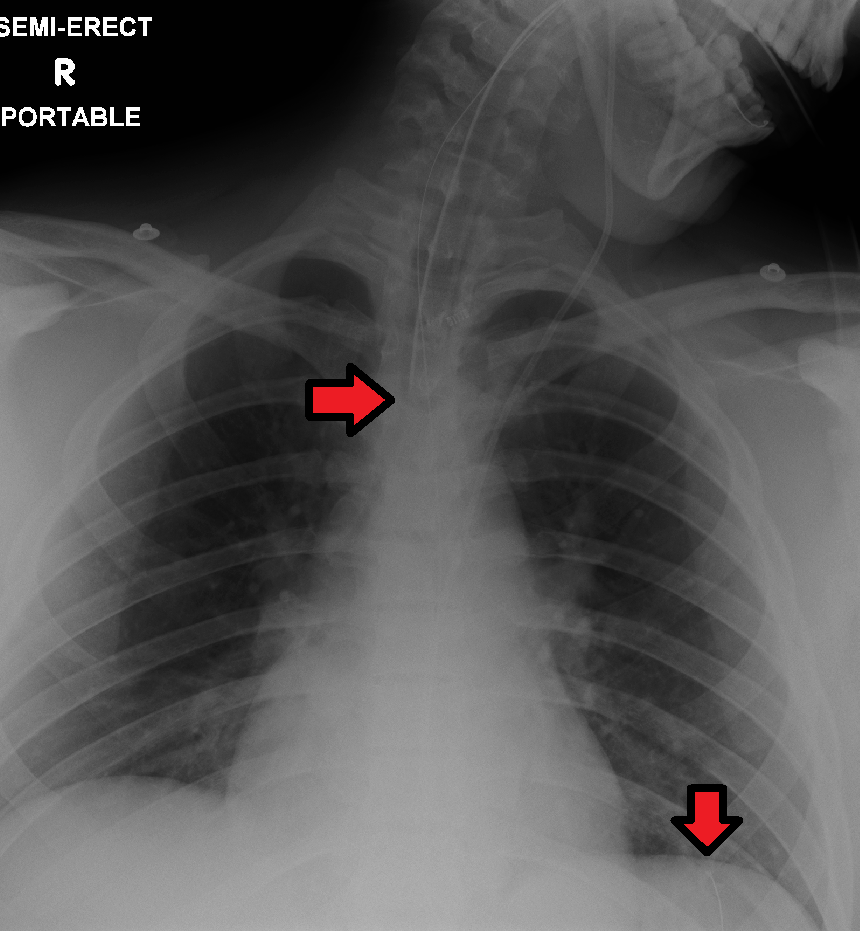

Feedings or medications administered into an incorrectly placed enteral tube result in life-threatening aspiration pneumonia. The placement of an enteral tube is immediately verified after insertion by an X-ray to ensure it has not been inadvertently placed into the trachea and down into the bronchi. See Figure 17.6[8] for an image of an X-ray demonstrating correct placement of an enteral tube in the stomach as indicated by the lower red arrow. (This X-ray also demonstrates an endotracheal tube correctly placed in the trachea as indicated by the top arrow.) After X-ray verification, the tube should be marked with adhesive tape and/or a permanent marker to indicate the point on the tube where the feeding tube enters the nares or penetrates the abdominal wall. This number on the tube at the entry point should be documented in the medical record and communicated during handoff reports. At the start of every shift, nurses evaluate if the incremental marking or external tube length has changed. If a change is observed, bedside tests such as visualization or pH testing of tube aspirate can help determine if the tube has become dislocated. If in doubt, a radiograph should be obtained to determine tube location.[9]

After the initial verification of tube placement by X-ray, it is possible for the tube to migrate out of position due to the patient coughing, vomiting, and moving. For this reason, the nurse must routinely check tube placement before every use. The American Association of Critical‐Care Nursing recommends that the position of a feeding tube should be checked and documented every four hours and prior to the administration of enteral feedings and medications by measuring the visible tube length and comparing it to the length documented during X-ray verification.[10],[11],[12]

Older methods of checking tube placement included observing aspirated GI contents or the administration of air with a syringe while auscultating (commonly referred to as the “whoosh test”). However, research has determined these methods are unreliable and should no longer be used to verify placement.[13],[14]

Checking the pH of aspirated gastric contents is an alternative method to verify placement that may be used in some agencies. Gastric aspirate should have a pH of less than or equal to 5.5 using pH indicator paper that is marked for use with human aspirate. However, caution should be used with this method because enteral formula and some medications alter the gastric pH.[15]

Follow agency policy for assessing and documenting tube placement. Additionally, if the patient develops respiratory symptoms that indicate potential aspiration, immediately notify the provider and withhold enteral feedings and medications until the placement is verified.

Assessing and Cleaning the Tube Insertion Site

The area of tube insertion should be assessed daily for signs of pressure damage. For NG tubes, the adhesive used to secure the tube can be irritating and cause skin breakdown. PEG and PEJ tubes may have fluid seepage around the insertion point that can cause skin breakdown if not cleaned regularly. Follow agency policy for cleansing the external insertion site for PEG and PEJ tubes. Cleansing is typically performed using gauze moistened with water or saline and then allowed to air dry before the fixation plate is repositioned. Because skin surrounding the insertion site is prone to breakdown, barrier cream or dressings may be prescribed to prevent breakdown.[16],[17]

Tube Feeding

Enteral nutrition (EN) refers to nutrition provided directly into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through an enteral route that bypasses the oral cavity. Each year in the United States, over 250,000 hospitalized patients from infants to older adults receive EN. It is also used widely in rehabilitation, long‐term care, and home settings. EN requires a multidisciplinary team approach, including a registered dietician, health care provider, pharmacist, and bedside nurses. The registered dietician performs a nutrition assessment and determines what type of enteral nutrition is appropriate to promote improved patient outcomes. The health care provider writes the order for the enteral nutrition. Prescriptions for enteral nutrition should be reviewed by the nurse for the following components: type of enteral nutrition formula, amount and frequency of free water flushes, route of administration, administration method, and rate. Any concerns about the components of the prescription should be verified with the provider before tube feeding is administered.[18]

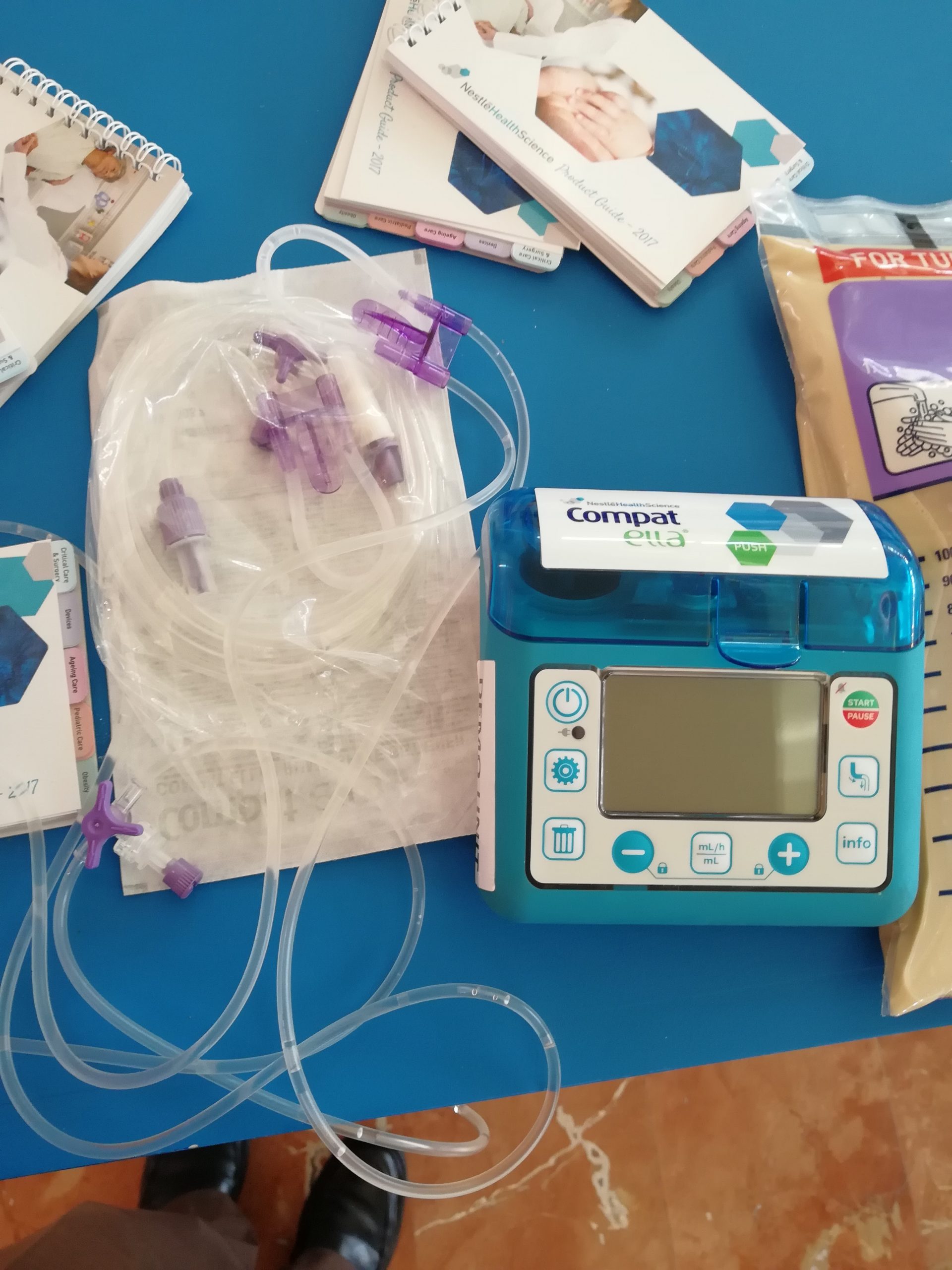

Tube feeding can be administered using gravity to provide a bolus feeding or via a pump to provide continuous or intermittent feeding. Feedings via a pump are set up in mL/hr, with the rate prescribed by the health care provider. See Figure 17.7[19] for an image of an enteral tube feeding pump and the associated tubing. Note that tubing used for enteral feeding is indicated by specific colors (such as purple in Figure 17.7). A global safety initiative, referred to as “EnFit,” is in progress to ensure all devices used with enteral feeding, such as extension sets, syringes, PEG tubes, and NG tubes have specific EnFit ends that can only be used with tube feeding sets. This new safety design will avoid inadvertent administration of enteral feeding into intravenous tubing that can cause life-threatening adverse effects.

Review the “Checklist for NG Tube Enteral Feeding by Gravity With Irrigation” section for additional information regarding administering bolus feedings by gravity.

Life Span Considerations

Enteral feeding is administered to infants and children via a syringe, gravity feeding set, or feeding pump. The method selected is dependent on the nature of the feeding and clinical status of the child.[20]

Complications of Enteral Feeding

The most serious complication of enteral feeding is inadvertent respiratory aspiration of gastric contents, causing life-threatening aspiration pneumonia. Other complications include tube clogging, tubing misconnections, and patient intolerance of enteral feeding.[21]

Reducing Risk of Aspiration

In addition to verifying tube placement as discussed in an earlier section, nurses perform additional interventions to prevent aspiration. The American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses recommends the following guidelines to reduce the risk for aspiration:

- Maintain the head of the bed at 30°-45° unless contraindicated

- Use sedatives as sparingly as possible

- Assess feeding tube placement at four‐hour intervals

- Observe for change in the amount of external length of the tube

- Assess for gastrointestinal intolerance at four‐hour intervals[22]

Measurement of gastric residual volume (GRV) is performed by using a 60-mL syringe to aspirate stomach contents through the tube. It has traditionally been used to assess aspiration risk with associated interventions such as slowing or stopping the enteral feeding. GRVs in the range of 200–500 mL cause interventions such as slowing or stopping the feeding to reduce risk of aspiration. However, according to recent research, it is not appropriate to stop enteral nutrition for GRVs less than 500 mL in the absence of other signs of intolerance because of the impact on the patient’s overall nutritional status. Additionally, the aspiration of gastric residual volumes can contribute to tube clogging.[23] Follow agency policy regarding measuring gastric residual volume and implementing interventions to prevent aspiration.

Managing Tube Clogging

Feeding tubes are prone to clogging for a variety of reasons. The risk of clogging may result from tube properties (such as narrow tube diameter), the tube tip location (stomach vs. small intestine), insufficient water flushes, aspiration for gastric residual volume (GRV), contaminated formula, and incorrect medication preparation and administration. A clogged feeding tube can result in decreased nutrient delivery or delayed administration of medication, and, if not corrected, the patient may require additional surgical intervention to replace the tube.[24]

Research supports using water as the best choice for initial declogging efforts. Instill warm water into the tube using a 60‐mL syringe and apply a gentle back‐and‐forth motion with the plunger of the syringe. Research shows that the use of cranberry juice and carbonated beverages to flush the tube can worsen tube occlusions because the acidic pH of these fluids can cause proteins in the enteral formula to precipitate within the tube. If water does not work, a pancreatic enzyme solution, an enzymatic declogging kit, or mechanical devices for clearing feeding tubes are the best second‐line options.[25]

To prevent enteral tubes from clogging, it is important to follow these guidelines:

- Flush feeding tubes at a minimum of once a shift.

- Flush feeding tubes immediately before and after intermittent feedings. During continuous feedings, flush at standardized, scheduled intervals.

- Flush feeding tubes before and after medication administration and follow appropriate medication administration practices.

- Limit gastric residual volume checks because the acidic gastric contents may cause protein in enteral formulas to precipitate within the lumen of the tube.[26]

Preventing Tubing Misconnections

In April 2006, The Joint Commission issued a Sentinel Event Alert on tubing misconnections due to enteral feedings being inadvertently infused into intravenous lines with life-threatening results. A color-coded enteral tubing connection design was developed to visually communicate the difference between enteral tubing and intravenous tubing. In addition to tubing design, follow these guidelines to prevent tubing misconnection errors:

- Make tubing connections under proper lighting.

- Do not modify or adapt IV or feeding devices because doing so may compromise the safety features incorporated into their design.

- When making a reconnection, routinely trace lines back to their origins and then ensure that they are secure.

- As part of a hand‐off process, recheck connections and trace all tubes back to their origins.[27]

Managing Intolerances and Imbalances

Patients should be monitored daily for signs of tube feeding intolerance, such as abdominal bloating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramping, and constipation. If cramping occurs during bolus feedings, it can be helpful to administer the enteral nutritional formula at room temperature to prevent symptoms.[28] Notify the provider of signs of intolerance with anticipated changes in the prescription regarding the type of formula or the rate of administration. Electrolytes and blood glucose levels should also be monitored, as ordered, for signs of imbalances.[29],[30]

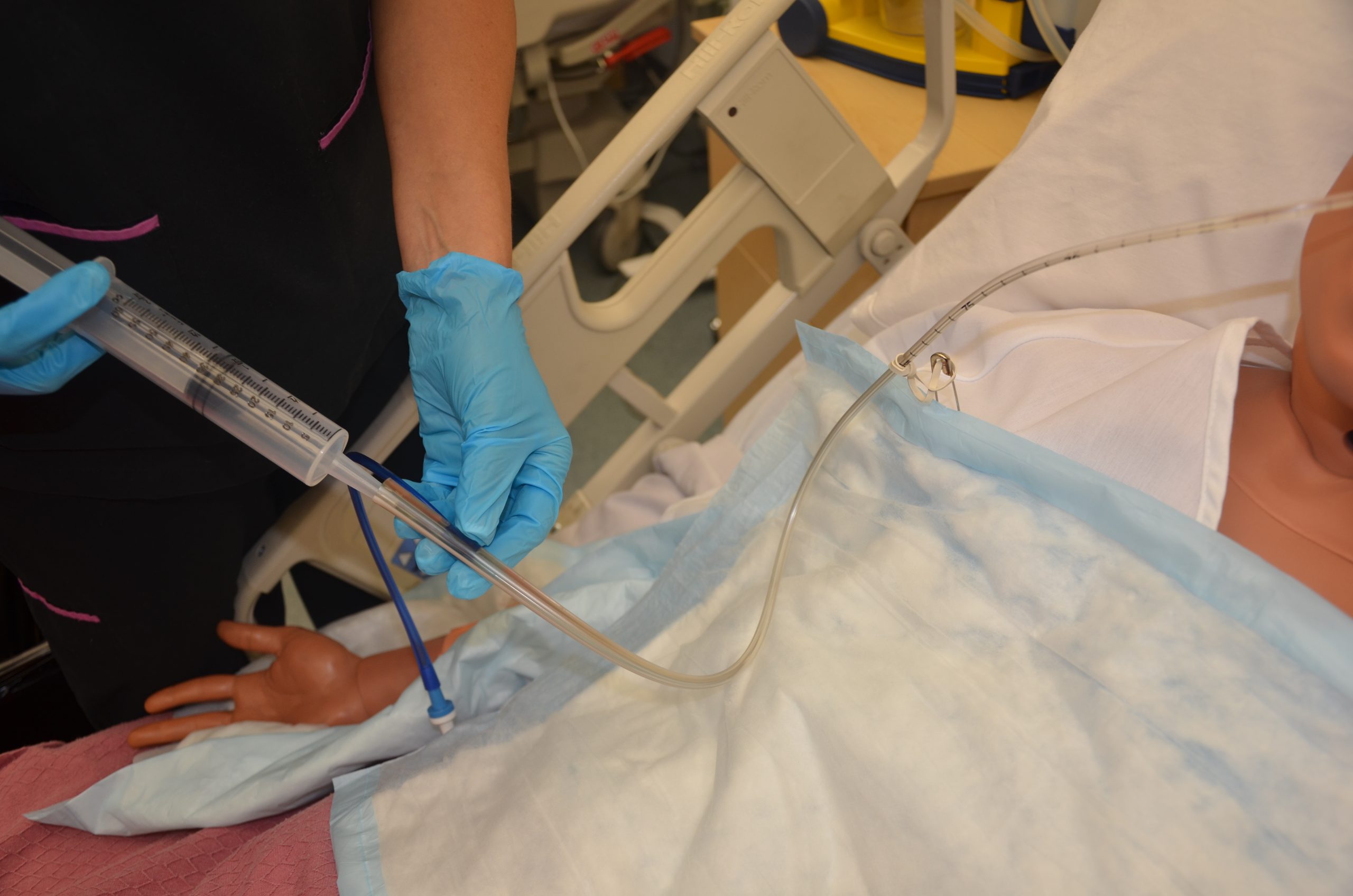

Tube Irrigation

Enteral tubes are routinely flushed to maintain patency. Follow agency policy when flushing a tube. Typically, tap water and a 60-mL syringe are used to flush enteral tubes.[31] See Figure 17.8[32] for an image of a nurse irrigating an NG tube.

The steps for irrigating enteral tubes are typically the following:

- Draw the required amount of water into the 60-mL syringe and dispel excess air.

- If the tube has a clamp, close it.

- Open the distal end of the tube and connect the syringe.

- Open the clamp.

- Administer the water.

- Close the clamp.

- Remove the syringe and refill it with water if indicated.

- Repeat as needed to obtain the desired flushing volume.

- Once completed, remove the syringe, close the tube cap, and reopen the clamp.[33]

Tube Suctioning

NG tubes may be used to remove gastric content, referred to as gastric decompression. In these situations, the stomach is drained by gravity or by connection to a suction pump to prevent nausea, vomiting, gastric distension, or to wash the stomach of toxins. This procedure is commonly used for postoperative patients who have not yet regained peristalsis or for patients with a small bowel obstruction to remove the accumulation of stomach bile. It is also used in the emergency department for patients with some types of poisonings or overdoses and is commonly referred to as “pumping out the stomach.”

For patients receiving suctioning via enteral tubes, the drainage amount and color should be documented every shift.

View a supplementary YouTube video on Tube Feeding Calculations[34]

- “abdomen-intestine-large-small-1698565” by bodymybody is licensed under CCO ↵

- Wireko, B. M., & Bowling, T. (2010). Enteral tube feeding. Clinical Medicine, 10(6), 616–619. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.10-6-616 ↵

- “Types and Placement of Enteral Tubes.png” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- “Enteral_feeding_tube_stylet_retracted.png” by Tenbergen is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Silicone_dual_lumen_stomach_tube_with_plug_removed.png” by Tenbergen is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “PEG_tube_kit.jpg” by Gilo1969 and “Percutaneous_endoscopic_gastrostomy-tube.jpg” by Pflegewiki-User HoRaMi are licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “ETTubeandNGtubeMarked.png” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Lemyze, M. (2010). The placement of nasogastric tubes. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(8), 802. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.091099 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Simons, S. R., & Abdallah, L. M. (2012). Bedside assessment of enteral tube placement: Aligning practice with evidence. American Journal of Nursing, 112(2), 40-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000411178.07179.68 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- “Open_system_enteral_feeding.jpg” by Ashashyou is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. (2017, December). Enteral feeding and medication administration. https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Enteral_feeding_and_medication_administration/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne. (2017, December). Enteral feeding and medication administration. https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Enteral_feeding_and_medication_administration/ ↵

- Blumenstein, I., Shastri, Y. M., & Stein, J. (2014). Gastroenteric tube feeding: Techniques, problems and solutions. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 20(26), 8505–8524. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505 ↵

- Boullata, J. I., Carrera, A. L., Harvey, L., Escuro, A. A., Hudson, L., Mays, A., McGinnis, C., Wessel, J. J., Bajpai, S., Beebe, M. L., Kinn, T. J., Klang, M. G., Lord, L., Martin, K., Pompeii‐Wolfe, C., Sullivan, J., Wood, A., Malone, A., & Guenter, P. (2017). ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 41(1), 15-103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148607116673053 ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- “DSC_1667.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/10-2-nasogastric-tubes ↵

- Best, C. (2019). Selection and management of commonly used enteral feeding tubes. Nursing Times, 15(3), 43-47. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/nutrition/selection-and-management-of-commonly-used-enteral-feeding-tubes-18-02-2019/ ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, May 18). Tube feeding nursing calculations problems dilution enteral [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/CwfJ-sQ-xOQ ↵

The first IPEC competency is related to values and ethics and states, “Work with individuals of other professions to maintain a climate of mutual respect and shared values.”[1] See the box below for the components related to this competency. Notice how these interprofessional competencies are very similar to the Standards of Professional Performance established by the American Nurses Association related to Ethics, Advocacy, Respectful and Equitable Practice, Communication, and Collaboration.[2]

Components of IPEC’s Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice Competency[3]

- Place interests of clients and populations at the center of interprofessional health care delivery and population health programs and policies, with the goal of promoting health and health equity across the life span.

- Respect the dignity and privacy of patients while maintaining confidentiality in the delivery of team-based care.

- Embrace the cultural diversity and individual differences that characterize patients, populations, and the health team.

- Respect the unique cultures, values, roles/responsibilities, and expertise of other health professions and the impact these factors can have on health outcomes.

- Work in cooperation with those who receive care, those who provide care, and others who contribute to or support the delivery of prevention and health services and programs.

- Develop a trusting relationship with patients, families, and other team members.

- Demonstrate high standards of ethical conduct and quality of care in contributions to team-based care.

- Manage ethical dilemmas specific to interprofessional patient/population-centered care situations.

- Act with honesty and integrity in relationships with patients, families, communities, and other team members.

- Maintain competence in one’s own profession appropriate to scope of practice.

Nursing, medical, and other health professional programs typically educate students in “silos” with few opportunities to collaboratively work together in the classroom or in clinical settings. However, after being hired for their first job, these graduates are thrown into complex clinical situations and expected to function as part of the team. One of the first steps in learning how to function as part of an effective interprofessional team is to value each health care professional’s contribution to quality, patient-centered care. Mutual respect and trust are foundational to effective interprofessional working relationships for collaborative care delivery across the health professions. Collaborative care also honors the diversity reflected in the individual expertise each profession brings to care delivery.[4]

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among clients, family members, and health care team members. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique, and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[5] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, “A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.”[6] It is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice and interprofessional collaborative practice.

Read more about cultural diversity, cultural humility, and integrating culturally responsive care in the “Diverse Patients” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Nurses value the expertise of interprofessional team members and integrate this expertise when providing patient-centered care. Some examples of valuing and integrating the expertise of interprofessional team members include the following:

- A nurse is caring for a patient admitted with chronic heart failure to a medical-surgical unit. During the shift the patient’s breathing becomes more labored and the patient states, “My breathing feels worse today.” The nurse ensures the patient’s head of bed is elevated, oxygen is applied according to the provider orders, and the appropriate scheduled and PRN medications are administered, but the patient continues to complain of dyspnea. The nurse calls the respiratory therapist and requests a STAT consult. The respiratory therapist assesses the patient and recommends implementation of BiPAP therapy. The provider is notified and an order for BiPAP is received. The patient reports later in the shift the dyspnea is resolved with the BiPAP therapy.

- A nurse is working in the Emergency Department when an adolescent patient arrives via ambulance experiencing a severe asthma attack. The paramedic provides a handoff report with the patient's current vital signs, medications administered, and intravenous (IV) access established. The paramedic also provides information about the home environment, including information about vaping products and a cat in the adolescent’s bedroom. The nurse thanks the paramedic for sharing these observations and plans to use information about the home environment to provide patient education about asthma triggers and tobacco cessation after the patient has been stabilized.

- A nurse is working in a long-term care environment with several assistive personnel (AP) who work closely with the residents providing personal cares and have excellent knowledge regarding their baseline status. Today, after helping Mrs. Smith with her morning bath, one of the APs tells the nurse, “Mrs. Smith doesn’t seem like herself today. She was very tired and kept falling asleep while I was talking to her, which is not her normal behavior.” The nurse immediately assesses Mrs. Smith and confirms her somnolescence and confirms her vital signs are within her normal range. The nurse reviews Mrs. Smith’s chart and notices that a new prescription for furosemide was started last month but no potassium supplements were ordered. The nurse notifies the provider of the patient’s change in status and receives an order for lab work including an electrolyte panel. The results indicate that Mrs. Smith’s potassium level has dropped to an abnormal level, which is the likely cause of her fatigue and somnolescence. The provider is notified, and an order is received for a potassium supplement. The nurse thanks the AP for recognizing and reporting Mrs. Smith’s change in status and successfully preventing a poor patient outcome such as a life-threatening cardiac dysrhythmia.

Effective patient-centered, interprofessional collaborative practice improves patient outcomes. View supplementary material and reflective questions in the following box.[7]

View the “How does interprofessional collaboration impact care: The patient’s perspective?” video on YouTube regarding patients' perspectives about the importance of interprofessional collaboration.

Read Ten Lessons in Collaboration. Although this is an older publication, it provides ten lessons to consider in collaborative relationships and practice. The discussion reflects many components of collaboration that have been integral to nursing practice in interprofessional teamwork and leadership.

Reflective Questions

- What is the difference between patient-centered care and disease-centered care?

- Why is it important for health professionals to collaborate?

The third IPEC competency focuses on interprofessional communication and states, “Communicate with patients, families, communities, and professionals in health and other fields in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the promotion and maintenance of health and the prevention and treatment of disease.”[8] See Figure 7.1[9] for an image of interprofessional communication supporting a team approach. This competency also aligns with The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goal for improving staff communication.[10] See the following box for the components associated with the Interprofessional Communication competency.

Components of IPEC’s Interprofessional Communication Competency[11]

- Choose effective communication tools and techniques, including information systems and communication technologies, to facilitate discussions and interactions that enhance team function.

- Communicate information with patients, families, community members, and health team members in a form that is understandable, avoiding discipline-specific terminology when possible.

- Express one’s knowledge and opinions to team members involved in patient care and population health improvement with confidence, clarity, and respect, working to ensure common understanding of information, treatment, care decisions, and population health programs and policies.

- Listen actively and encourage ideas and opinions of other team members.

- Give timely, sensitive, constructive feedback to others about their performance on the team, responding respectfully as a team member to feedback from others.

- Use respectful language appropriate for a given difficult situation, crucial conversation, or conflict.

- Recognize how one’s uniqueness (experience level, expertise, culture, power, and hierarchy within the health care team) contributes to effective communication, conflict resolution, and positive interprofessional working relationships.

- Communicate the importance of teamwork in patient-centered care and population health programs and policies.

Transmission of information among members of the health care team and facilities is ongoing and critical to quality care. However, information that is delayed, inefficient, or inadequate creates barriers for providing quality of care. Communication barriers continue to exist in health care environments due to interprofessional team members’ lack of experience when interacting with other disciplines. For instance, many novice nurses enter the workforce without experiencing communication with other members of the health care team (e.g., providers, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, surgical staff, dieticians, physical therapists, etc.). Additionally, health care professionals tend to develop a professional identity based on their educational program with a distinction made between groups. This distinction can cause tension between professional groups due to diverse training and perspectives on providing quality patient care. In addition, a health care organization’s environment may not be conducive to effectively sharing information with multiple staff members across multiple units.

In addition to potential educational, psychological, and organizational barriers to sharing information, there can also be general barriers that impact interprofessional communication and collaboration. See the following box for a list of these general barriers.[12]

General Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[13]

- Personal values and expectations

- Personality differences

- Organizational hierarchy

- Lack of cultural humility

- Generational differences

- Historical interprofessional and intraprofessional rivalries

- Differences in language and medical jargon

- Differences in schedules and professional routines

- Varying levels of preparation, qualifications, and status

- Differences in requirements, regulations, and norms of professional education

- Fears of diluted professional identity

- Differences in accountability and reimbursement models

- Diverse clinical responsibilities

- Increased complexity of patient care

- Emphasis on rapid decision-making

There are several national initiatives that have been developed to overcome barriers to communication among interprofessional team members. These initiatives are summarized in Table 7.5a.[14]

Table 7.5a. Initiatives to Overcome Barriers to Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration[15]

| Action | Description |

|---|---|

| Teach structured interprofessional communication strategies | Structured communication strategies, such as ISBARR, handoff reports, I-PASS reports, and closed-loop communication should be taught to all health professionals. |

| Train interprofessional teams together | Teams that work together should train together. |

| Train teams using simulation | Simulation creates a safe environment to practice communication strategies and increase interdisciplinary understanding. |

| Define cohesive interprofessional teams | Interprofessional health care teams should be defined within organizations as a cohesive whole with common goals and not just a collection of disciplines. |

| Create democratic teams | All members of the health care team should feel valued. Creating democratic teams (instead of establishing hierarchies) encourages open team communication. |

| Support teamwork with protocols and procedures | Protocols and procedures encouraging information sharing across the whole team include checklists, briefings, huddles, and debriefing. Technology and informatics should also be used to promote information sharing among team members. |

| Develop an organizational culture supporting health care teams | Agency leaders must establish a safety culture and emphasize the importance of effective interprofessional collaboration for achieving good patient outcomes. |

Communication Strategies

Several communication strategies have been implemented nationally to ensure information is exchanged among health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to promote safe patient care. Examples of these initiatives are ISBARR, handoff reports, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS. Documentation that promotes sharing information interprofessionally to promote continuity of care is also essential. These strategies are discussed in the following subsections.

ISBARR

A common format used by health care team members to exchange client information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.[16],[17]

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the client’s name and location, the reason you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the client.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the client such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current client situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the client, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the client’s chart.

Nursing Considerations

Before using ISBARR to call a provider regarding a changing client condition or concern, it is important for nurses to prepare and gather appropriate information. See the following box for considerations when calling the provider.

Communication Guidelines for Nurses[18]

- Have I assessed this client before I call?

- Have I reviewed the current orders?

- Are there related standing orders or protocols?

- Have I read the most recent provider and nursing progress notes?

- Have I discussed concerns with my charge nurse, if necessary?

- When ready to call, have the following information on hand:

- Admitting diagnosis and date of admission

- Code status

- Allergies

- Most recent vital signs

- Most recent lab results

- Current meds and IV fluids

- If receiving oxygen therapy, current device and L/min

- Before calling, reflect on what you expect to happen as a result of this call and if you have any recommendations or specific requests.

- Repeat back any new orders to confirm them.

- Immediately after the call, document with whom you spoke, the exact time of the call, and a summary of the information shared and received.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane Smith, RN from the Med-Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96% on room air, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site, and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Her lungs are clear, and her heart rate is regular. She has no allergies. I think she has developed a wound infection.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.”[19] In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors.[20]

The Joint Commission encourages the standardization of critical content to be communicated by interprofessional team members during a handoff report both verbally (preferably face to face) and in written form. Critical content to communicate to the receiver in a handoff report includes the following components[21]:

- Sender contact information

- Illness assessment, including severity

- Patient summary, including events leading up to illness or admission, hospital course, ongoing assessment, and plan of care

- To-do action list

- Contingency plans

- Allergy list

- Code status

- Medication list

- Recent laboratory tests

- Recent vital signs

Several strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented nationally, such as the Bedside Handoff Report Checklist, closed-loop communication, and I-PASS.

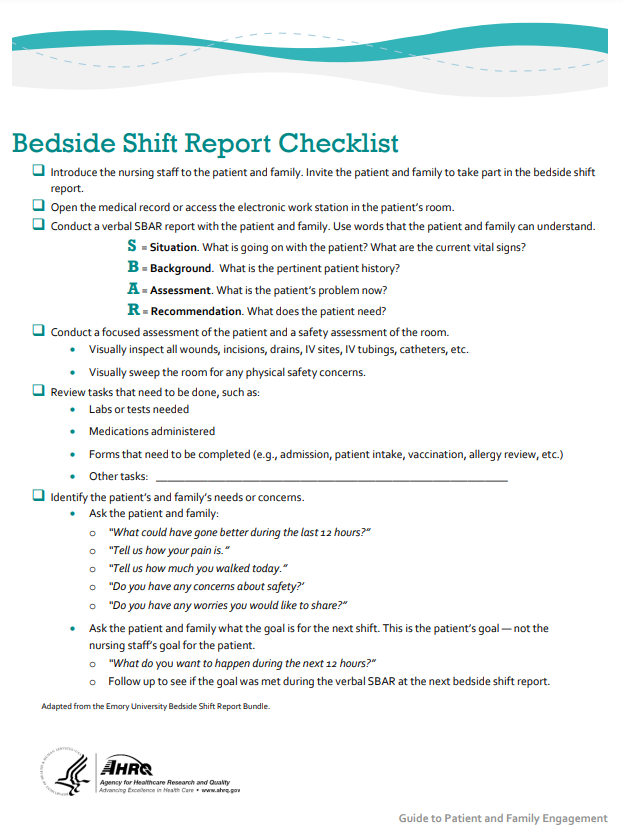

Bedside Handoff Report Checklist

See Figure 7.2[22] for an example of a Bedside Handoff Report Checklist to improve nursing handoff reports by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).[23] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts.

Print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist.[24]

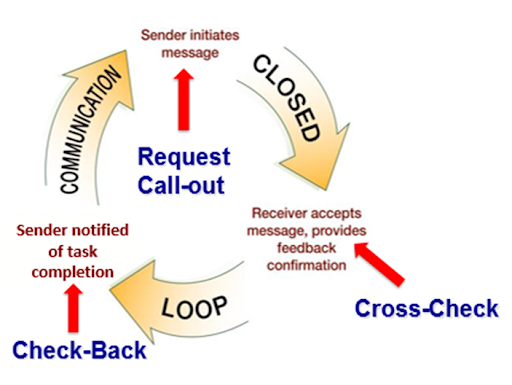

Closed-Loop Communication

The closed-loop communication strategy is used to ensure that information conveyed by the sender is heard by the receiver and completed. Closed-loop communication is especially important during emergency situations when verbal orders are being provided as treatments are immediately implemented. See Figure 7.3[25] for an illustration of closed-loop communication.

- The sender initiates the message.

- The receiver accepts the message and repeats back the message to confirm it (i.e., “Cross-Check”).

- The sender confirms the message.

- The receiver notified the sender the task was completed (i.e., “Check-Back”).

See an example of closed-loop communication during an emergent situation in the following box.

Closed-Loop Communication Example

Doctor: "Administer 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT."

Nurse: "Give 25 mg Benadryl IV push STAT?"

Doctor: "That's correct."

Nurse: "Benadryl 25 mg IV push given at 1125."

I-PASS

I-PASS is a mnemonic used to provide structured communication among interprofessional team members. I-PASS stands for the following components[26]:

I: Illness severity

P: Patient summary

A: Action list

S: Situation awareness and contingency plans

S: Synthesis by receiver (i.e., closed-loop communication)

See a sample I-PASS Handoff in Table 7.5b.[27]

Table 7.5b. Sample I-PASS Verbal Handoff[28]

| I | Illness Severity | This is our sickest patient on the unit, and he's a full code. |

|---|---|---|

| P | Patient Summary | AJ is a 4-year-old boy admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to left lower lobe pneumonia. He presented with cough and high fevers for two days before admission, and on the day of admission to the emergency department, he had worsening respiratory distress. In the emergency department, he was found to have a sodium level of 130 mg/dL likely due to volume depletion. He received a fluid bolus, and oxygen administration was started at 2.5 L/min per nasal cannula. He is on ceftriaxone. |

| A | Action List | Assess him at midnight to ensure his vital signs are stable. Check to determine if his blood culture is positive tonight. |

| S | Situations Awareness & Contingency Planning | If his respiratory distress worsens, get another chest radiograph to determine if he is developing an effusion. |

| S | Synthesis by Receiver | Ok, so AJ is a 4-year-old admitted with hypoxia and respiratory distress secondary to a left lower lobe pneumonia receiving ceftriaxone, oxygen, and fluids. I will assess him at midnight to ensure he is stable and check on his blood culture. If his respiratory status worsens, I will repeat a radiograph to look for an effusion. |

Listening Skills

Effective team communication includes both the delivery and receipt of the message. Listening skills are a fundamental element of the communication loop. For nursing staff, this involves listening to clients, families, and coworkers. Active listening involves not just hearing the individual words that someone states, but also understanding the emotions and concerns behind the words. Employing active listening reflects an empathetic approach and can improve client outcomes and foster teamwork.

Nurses often serve as the communication bridge between clients, families, and other health care team members. By listening attentively to colleagues, nurses can ensure that important information is accurately conveyed, reducing the risk of misunderstandings and enhancing the overall efficiency of care delivery. This collaborative environment fosters a culture of mutual respect and support, ultimately leading to better health care outcomes.

In order to develop active listening skills, individuals should practice mindfulness and practice their communication techniques. Listening skills can be cultivated with eye contact, actions such as nodding, and demonstration of other nonverbal strategies to demonstrate engagement. Maintaining an open posture, smiling, and attentiveness are all nonverbal strategies that can facilitate communication. It is important to take measures to avoid distractions, offer a summation of the communication, and ask clarifying questions to further develop the communication.

Documentation

Accurate, timely, concise, and thorough documentation by interprofessional team members ensures continuity of care for their clients. It is well-known by health care team members that in a court of law the rule of thumb is, “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Any type of documentation in the electronic health record (EHR) is considered a legal document. Abbreviations should be avoided in legal documentation and some abbreviations are prohibited. Please see a list of error prone abbreviations in the box below.

Read the current list of error-prone abbreviations by the Institute of Safe Medication Practices. These abbreviations should never be used when communicating medical information verbally, electronically, and/or in handwritten applications. Abbreviations included on The Joint Commission’s “Do Not Use” list are identified with a double asterisk (**) and must be included on an organization’s “Do Not Use” list.

Nursing staff access the electronic health record (EHR) to help ensure accuracy in medication administration and document the medication administration to help ensure patient safety. Please see Figure 7.4[29] for an image of a nurse accessing a client’s EHR.

Electronic Health Record

The electronic health record (EHR) contains the following important information:

- History and Physical (H&P): A history and physical (H&P) is a specific type of documentation created by the health care provider when the client is admitted to the facility. An H&P includes important information about the client’s current status, medical history, and the treatment plan in a concise format that is helpful for the nurse to review. Information typically includes the reason for admission, health history, surgical history, allergies, current medications, physical examination findings, medical diagnoses, and the treatment plan.

- Provider orders: This section includes the prescriptions, or medical orders, that the nurse must legally implement or appropriately communicate according to agency policy if not implemented.

- Medication Administration Records (MARs): Medications are charted through electronic medication administration records (MARs). These records interface the medication orders from providers with pharmacists and are also the location where nurses document medications administered.

- Treatment Administration Records (TARs): In many facilities, treatments are documented on a treatment administration record.

- Laboratory results: This section includes results from blood work and other tests performed in the lab.

- Diagnostic test results: This section includes results from diagnostic tests ordered by the provider such as X-rays, ultrasounds, etc.

- Progress notes: This section contains notes created by nurses, providers, and other interprofessional team members regarding client care. It is helpful for the nurse to review daily progress notes by all team members to ensure continuity of care.

- Nursing care plans: Nursing care plans are created by registered nurses (RNs). Documentation of individualized nursing care plans is legally required in long-term care facilities by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and in hospitals by The Joint Commission. Nursing care plans are individualized to meet the specific and unique needs of each client. They contain expected outcomes and planned interventions to be completed by nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. As part of the nursing process, nurses routinely evaluate the client’s progress toward meeting the expected outcomes and modify the nursing care plan as needed. Read more about nursing care plans in the “Planning” section of the “Nursing Process” chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Read the American Nurses Association’s Principles for Nursing Documentation.