Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that we have discussed basic concepts and the nursing process related to the grieving process, let’s discuss more details regarding providing palliative care. Nurses provide palliative care whenever caring for clients with chronic disease. As the disease progresses and becomes end-stage, the palliative care they provide becomes even more important. As previously discussed in the “Basic Concepts” section, palliative care is client and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care occurs throughout the continuum of care and involves the interdisciplinary team collaboratively addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and facilitating client autonomy, access to information, and choice.”[1]

Providing care at the end of life is similar for clients with a broad variety of medical diagnoses. It addresses multiple dimensions of care, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects:

- Physical: Functional ability, strength/fatigue, sleep/rest, nausea, appetite, constipation, and pain

- Psychological: Anxiety, depression, enjoyment/leisure, pain, distress, happiness, fear, and cognition/attention

- Social: Financial burden, caregiver burden, roles/relationships, affection, and appearance

- Spiritual: Hope, suffering, the meaning of pain, religiosity, and transcendence[2]

The interdisciplinary team manages pain and other symptoms, assists with difficult medical decisions, and provides additional support to clients, family members, and caregivers. Nurses have the opportunity to maintain hope for clients and family members by providing excellent physical, psychosocial, and spiritual palliative care. Nursing interventions begin immediately after the initial medical diagnosis and continue throughout the continuum of care until the end of life. As a client approaches end-of-life care, nursing interventions include the following:

- Eliciting the client’s goals for care

- Listening to the client and their family members

- Communicating with members of the interdisciplinary team and advocating for the client’s wishes

- Managing end-of-life symptoms

- Encouraging reminiscing

- Facilitating participating in religious rituals and spiritual practices

- Making referrals to chaplains, clergy, and other spiritual support[3]

While providing palliative care, it is important to remain aware that some things cannot be “fixed”:

- We cannot change the inevitability of death.

- We cannot change the anguish felt when a loved one dies.

- We must all face the fact that we, too, will die.

- The perfect words or interventions rarely exist, so providing presence is vital.[4]

The Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin contains excellent resources for nurses providing care for seriously ill clients.

View the “Fast Facts” page for extensive information about palliative care and end-of-life topics.

Management of Common Symptoms

Many clients with serious, life-limiting illnesses have common symptoms that the nurse can assess, prevent, and manage to optimize their quality of life. These symptoms include pain, dyspnea, cough, anorexia and cachexia, constipation, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, depression, anxiety, cognitive changes, fatigue, pressure injuries, seizures, and sleep disturbances. Good symptom management improves quality of life and functioning at all states of chronic illness. Nurses play a critical role in recognizing these symptoms and communicating them to the interdisciplinary team for optimal management. The plan of care should always be based on the client’s goals and their definition of quality of life.[5] These common symptoms are discussed in the following subsections.

Pain

Pain is frequently defined as “whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever they say it does.”[6] When a client is unable to verbally report their pain, it is important to assess nonverbal and behavioral indicators of pain. The goal is to balance the client’s desire for pain relief, along with their desire to manage side effects and oversedation. There are many options available for analgesics. Reassure a client that reaching their goal of satisfactory pain relief is achievable. Read more about pain management in the “Comfort” chapter. See Figure 17.18[7] for an image illustrating a client experiencing pain.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a subjective experience of breathing discomfort and is the most reported symptom by clients with life-limiting illness. Dyspnea can be extremely frightening. Assessing dyspnea can be challenging because the client’s respiratory rate and oxygenation status do not always correlate with the symptom of breathlessness.[8] See Figure 17.19[9] for an image of a client depicting chest pain and dyspnea.

When assessing dyspnea, include the following components[10]:

- Ask the client to rate the severity of their breathlessness on a scale of 0-10

- Assess their ability to speak in sentences, phrases, or words

- Assess the client’s anxiety

- Observe respiratory rate and effort

- Measure oxygenation status (i.e., pulse oximetry or ABG)

- Auscultate lung sounds

- Assess for the presence of chest pain or other pain

- Assess factors that improve or worsen breathlessness

- Evaluate the impact of dyspnea on functional status and quality of life

If you suspect that new dyspnea is caused by an acute condition, report assessment findings immediately to a health care provider. Remember that acute illnesses are still addressed and treated for clients receiving palliative care. However, in end-stage disease, dyspnea can be a chronic condition that is treated with pharmacological and nonpharmacological management. Relatively small doses of opioids can be used to improve dyspnea while having little impact on respiratory status or a client’s life expectancy. Opioids help dilate pulmonary blood vessels, allowing more blood to flow to the lungs and lessening the work of breathing. The dosage should be titrated to the client’s desired goals for relief of dyspnea without over sedation.

Nonpharmacological interventions for dyspnea include pursed-lip breathing, energy conservation techniques, fans and open windows to circulate air, elevation of the client bed, placing the client in a tripod position, and relaxation techniques such as music and a calm, cool environment. Health teaching can also reduce anxiety.[11] Read more about nonpharmacological interventions for dyspnea in the “Oxygenation” chapter.

Cough

A cough can be frustrating and debilitating for a client, causing pain, fatigue, vomiting, and insomnia. See Figure 17.20[12] for an image of a person depicting a chronic cough. Coughing is frequently present in advanced diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF), cancer, and AIDS. Medications that can be used to control a cough are opioids, dextromethorphan, and benzonatate. Guaifenesin can be used to thin thick secretions, and anticholinergics (such as scopolamine) can be used for high-volume secretions.

Anorexia and Cachexia

Anorexia (loss of appetite or loss of desire to eat) and cachexia (wasting of muscle and adipose tissue due to lack of nutrition) are commonly found in advanced disease. See Figure 17.21[13] for an image of a client with cachexia. Weight loss is present in both conditions and is associated with decreased survival. Unfortunately, aggressive nutritional treatment does not improve survival or quality of life and can actually create more discomfort for the client as body systems begin to shut down as death approaches.[14]

Assessment of anorexia and cachexia focuses on understanding the client’s experience and concerns, as well as determining potentially reversible causes. Referral to a dietician may be needed. Read more about nutritional assessment in the “Nutrition” chapter.

Interventions for anorexia and cachexia should be individualized for each client with the goal being eating for pleasure for those at the end of life. Clients should be encouraged to eat their favorite foods, as well as select foods that are high in calories and easy to chew. Small, frequent meals with pleasing food presentation are important. Family members should be aware that odors associated with cooking can inhibit eating. The client may need to be moved away from the kitchen or cooking times separated from eating times.[15]

Medication may be prescribed to increase intake, such as mirtazapine or olanzapine. Prokinetics such as metoclopramide may be helpful in increasing gastric emptying. Medical marijuana or dronabinol may also be useful to stimulate appetite and reduce nausea. In some cases, enteral nutrition is helpful for clients who continue to have an appetite but cannot swallow.[16]

Health teaching for clients and family members about anorexia at the end of life is important. Nurses should be aware that many family members perceive eating as a way to “get better” and are distressed to see their loved one not eat. After listening respectfully to their concerns, explain that the client may feel more discomfort when forcing themselves to eat.

Constipation

Constipation is a frequent symptom in many clients at the end of life for many factors, such as low intake of food and fluids, use of opioids, chemotherapy, and impaired mobility. Constipation is defined as having less than three bowel movements per week. The client may experience associated symptoms such as rectal pressure, abdominal cramps, bloating, distension, and straining. See Figure 17.22[17] for an image of a client depicting symptoms of constipation.

The goal is to establish what is considered normal for each client and to have a bowel movement at least every 72 hours regardless of intake. Treatment includes a bowel regimen such as oral stool softeners (i.e., docusate) and a stimulant (i.e., sennosides). Rectal suppositories (i.e., bisacodyl) or enemas should be considered when oral medications are not effective, or the client can no longer tolerate oral medications.[18]

Read more about managing constipation in the “Elimination” chapter.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined as having more than three unformed stools in 24 hours. Diarrhea can be especially problematic for clients receiving chemotherapy, pelvic radiation, or treatment for AIDS because diarrhea is a common side effect of these treatments. It can cause dehydration, skin breakdown, and electrolyte imbalances and dramatically affect a person’s quality of life. It can also be a burden for caregivers due to frequent bathroom use or incontinence episodes.[19]

Early treatment of diarrhea includes promoting hydration with water or fluids that improve electrolyte status (i.e., sports drinks). Intravenous fluids may be required based on the client’s disease stage and goals for care. Medications such as loperamide, psyllium, and anticholinergic agents may also be prescribed to decrease the incidence of diarrhea.

Read more about managing diarrhea in the “Elimination” chapter.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea is common in advanced disease and is a dreaded side effect of many treatments for cancer. Assessment of nausea and vomiting should include the client’s history, effectiveness of previous treatment, medication history, frequency and intensity of episodes of nausea and vomiting, and activities that precipitate or alleviate nausea and vomiting.[20]

Nonpharmacological interventions for nausea include eating meals and fluids at room temperature, avoiding strong odors, avoiding high-bulk meals, using relaxation techniques, and listening to music therapy.[21] Aromatherapy using essential oils such as peppermint oil has been shown to significantly decrease the incidence of nausea and vomiting in hospitalized clients and those receiving chemotherapy.[22] Antiemetic medications, such as prochlorperazine and ondansetron, may be prescribed.

Read more information about managing nausea in the “Antiemetics” section of the Gastrointestinal chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e.

Depression

Clients who have a serious life-threatening illness will normally experience sadness, grief, and loss, but there is usually some capacity for pleasure. Persistent feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation are not considered a normal part of the grief process and should be treated. Undertreated depression can cause a decreased immune response, decreased quality of life, and decreased survival time. Evaluation of depression requires interdisciplinary assessment and referrals to social work and psychiatry may be needed.[23]

Antidepressants like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, or citalopram, are generally prescribed as first-line treatment of depression. Other medication may be prescribed if these medications are not effective.

Nonpharmacological interventions for depression may include the following:

- Promoting and facilitating as much autonomy and control as possible.

- Encouraging client and family participation in care, thus promoting a sense of control and reducing feelings of helplessness.

- Reminiscing and life review to focus on life accomplishments and to promote closure and resolution of life events. See Figure 17.23[24] for an image of reminiscing with pictures.

- Grief counseling to assist clients and families in dealing with loss.

- Maximizing symptom management.

- Referring to counseling for those experiencing inability to cope.

- Assisting the client to draw on previous sources of strength, such as faith, religious rituals, and spirituality.

- Referring for cognitive behavioral techniques to assist with reframing negative thoughts into positive thoughts.

- Teaching relaxation techniques.

- Providing ongoing emotional support and “being present.”

- Reducing isolation.

- Facilitating spiritual support.[25]

A suicide assessment is critical for a client with depression. It is important for nurses to ask questions, such as these:

- Do you have interest or pleasure in doing things?

- Have you had thoughts of harming yourself?

- If yes, do you have a plan for doing so?

To destigmatize the questions, it is helpful to phrase them in the following way, “It wouldn’t be unusual for someone in your circumstances to have thoughts of harming themselves. Have you had thoughts like that?” Clients with immediate, precise suicide plans and resources to carry out this plan should be immediately evaluated by psychiatric professionals.[26]

Anxiety

Anxiety is a subjective feeling of apprehension, tension, insecurity, and uneasiness, usually without a known specific cause. It may be anticipatory. It is assessed along a continuum as mild, moderate, or severe. Clients with life-limiting illness will experience various degrees of anxiety due to various issues such as their prognosis, mortality, financial concerns, uncontrolled pain and other symptoms, and feelings of loss of control.[27]

Physical symptoms of anxiety include sweating, tachycardia, restlessness, agitation, trembling, chest pain, hyperventilation, tension, and insomnia. Cognitive symptoms include recurrent and persistent thoughts and difficulty concentrating. See Figure 17.24[28] for an illustration of anxiety.

Benzodiazepines (i.e., lorazepam) may be prescribed to treat anxiety. However, the nurse should assess for adverse effects such as oversedation, falls, and delirium, especially in the frail elderly.

Nonpharmacological interventions are crucial and include the following[29]:

- Maximizing symptom management to decrease stressors

- Promoting the use of relaxation and guided imagery techniques, such as breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and the use of audiotapes

- Referring for psychiatric counseling for those unable to cope with the experience of their illness

- Facilitating spiritual support by contacting chaplains and clergy

- Acknowledging client fears and using open-ended questions and active listening with therapeutic communication

- Identifying effective coping strategies the client has used in the past, as well as teaching new coping skills such as relaxation and guided imagery techniques

- Providing concrete information to eliminate fear of the unknown

- Encouraging the use of a stress diary that helps the client understand the relationship between situations, thoughts, and feelings

Cognitive Changes

Delirium is a common cognitive disorder in hospitals and palliative care settings. Delirium is an acute change in cognition and requires urgent management in inpatient care. Up to 90% of clients at the end of life will develop delirium in their final days and hours of life. Early detection of delirium can cause resolution if the cause is reversible.[30]

Symptoms of delirium include agitation, confusion, hallucinations, or inappropriate behavior. It is important to obtain information from the caregiver to establish a mental status baseline. The most common cause of delirium at end of life is medication, followed by metabolic insufficiency due to organ failure.[31]

Medications such as neuroleptics (i.e., haloperidol and chlorpromazine) or benzodiazepines may be prescribed to manage delirium symptoms, but it is important to remember that delirium can be caused by opioid toxicity. It may be helpful to request the presence of family to reorient the patient, as well as provide nonpharmacological interventions such as massage, distraction, and relaxation techniques.[32]

Read more about delirium in the “Cognitive Impairments” chapter.

Fatigue

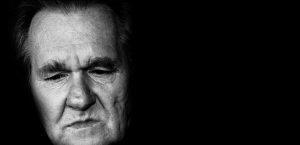

Fatigue has been cited as the most disabling condition for clients receiving a variety of treatments in palliative care. Fatigue is defined as a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion that is not proportional to activity and interferes with usual functioning.[33] See Figure 17.25[34] for an image of an older client depicting fatigue.

The primary cause of fatigue is metabolic alteration related to chronic disease, but it can also be caused by anemia, infection, poor sleep quality, chronic pain, and medication side effects. Nonpharmacological interventions include energy conservation techniques.

Pressure Injuries

Clients at end of life are at risk for quickly developing pressure injuries for a variety of reasons, including decreased nutrition and altered mobility. Prevention is key and requires interventions such as promoting mobility, frequent repositioning, reducing moisture, and encouraging nutrition as appropriate.

The Kennedy Terminal Ulcer is a type of pressure injury that some clients develop shortly before death resulting from multiorgan failure. It usually starts on the sacrum and is shaped like a pear, butterfly, or horseshoe. It is red, yellow, black, or purple in color with irregular borders and progresses quickly. For example, the injury may be identified by a nurse at the end of a shift who says, “That injury was not present when I assessed the client this morning.”[35]

Read more about assessing, preventing, and treating pressure injuries in the “Integumentary” chapter.

Seizures

Seizures are sudden, abnormal, excessive electrical impulses in the brain that alter neurological functions such as motor, autonomic, behavioral, and cognitive function. A seizure can be caused by infection, trauma, brain injury, brain tumors, side effects of medications, metabolic imbalances, drug toxicities, and withdrawal from medications.[36]

Seizures can have gradual or acute onset and include symptoms such as mental status changes, motor movement changes, and sensory changes. Treatment is focused on prevention and limiting trauma that may occur during the seizure. Medications such as phenytoin, phenobarbital, benzodiazepines, or levetiracetam may be prescribed to prevent or manage seizure activity.[37]

Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disturbances affect quality of life and can cause much suffering. It can be caused by poor pain and symptom management, as well as environmental disturbances. Nurses can promote improved sleep for inpatients by creating a quiet, calm environment, promoting sleep routines, and advocating for periods of uninterrupted rest without disruptions by the health care team.

Read more about promoting good sleep in the “Sleep and Rest” chapter.

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Pasero, C. (2018). In memoriam: Margo McCaffery, American Journal of Nursing, 118(3), 17. https://doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000530929.65995.42 ↵

- “a0dcf563-9393-4606-8302-c8f649e43895_rw_1200.jpg” by Flóra Borsi is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “1737708011-huge” by CGN089 is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- "1728210124-huge.jpg" by Pheelings media is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- “hospice-1794912_960_720.jpg” by truthseeker08 is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “abdominal-pain-2821941_960_720.jpg” by derneuemann is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Efe Ertürk, N., & Taşcı, S. (2021). The effects of peppermint oil on nausea, vomiting and retching in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: An open label quasi-randomized controlled pilot study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 56, 102587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102587. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “photos-256887_960_720.jpg” by jarmoluk is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “ANXIETY.jpg” by Jayberries is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- “fatigue_sleep_head_old_honey-454317.jpg” by danielam is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Care at the End of Life by Lowey and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

Before learning about cognitive impairment, it is important to understand the physiological processes of normal growth and development. Growth includes physical changes that occur during the development of an individual beginning at the time of conception. Development encompasses these biological changes, as well as social and cognitive changes that occur continuously throughout our lives. Cognition starts at birth and continues throughout the life span. See Figure 6.1[1] for an image of the human life cycle.

There are multiple factors that affect human cognitive development. While there are expected milestones along the way, cognitive development encompasses several different skills that develop at different rates. Cognition takes the form of many paths leading to unique developmental ends. Each human has their own individual experience that influences development of intelligence and reasoning as they interact with one another. With these unique experiences, everyone has a memory of feelings and events that is exclusive to them.[2]

Developmental Stages

As newborns, we learn behavior and communication to help us to interact with the world around us and to fulfill our needs. For example, crying provides communication to cue parents or caregivers about a newborn’s needs. The human brain undergoes tremendous development throughout the first year of life. As infants receive and experience input from the environment, they begin to interact with the individuals around them as they learn and grow.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development

Erikson’s psychosocial development theory emphasizes the social nature of our development rather than its sexual nature. It describes eight sequential stages of individual human development influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors throughout the life span that contribute to an individual's personality. Erikson’s stages of development are trust versus mistrust, autonomy versus shame, initiative versus guilt, industry versus inferiority, identity versus identity confusion, intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation, and integrity versus despair.[3],[4]

- Trust vs. Mistrust: The first stage that develops is trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met. Trust is the basis of our development during infancy (birth to 12 months). Infants are dependent upon their caregivers for their needs. Caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust, and the infant will perceive the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust, and the infant will perceive the world as unpredictable.[5]

- Autonomy vs. Shame: Toddlers begin to explore their world and learn that they can control their actions and act on the environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy versus shame and doubt by working to establish independence. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a two-year-old child who wishes to choose their own clothes and dress themselves. Although the outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, the input in basic decisions has an effect on the toddler’s sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on their environment, they may begin to doubt their abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.[6]

- Initiative vs. Guilt: After children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master a feeling of initiative and develop self-confidence and a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage may develop feelings of guilt.[7]

- Industry vs. Inferiority: During the elementary school stage (ages 7–11), children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they may feel inferior and inadequate if they feel they don’t measure up to their peers.[8]

- Identity vs. Identity Confusion: In adolescence (ages 12–18), children develop a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as, “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. Teens who do not make a conscious search for identity, or those who are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, may have a weak sense of self and experience role confusion as they are unsure of their identity and confused about the future.[9]

- Intimacy vs. Isolation: People in early adulthood (i.e., 20s through early 40s) are ready to share their lives and become intimate with others after they have developed a sense of self. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.[10]

- Generativity vs. Stagnation: When people reach their 40s, they enter a time period known as middle adulthood that extends to the mid-60s. The developmental task of middle adulthood is generativity versus stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. Adults who do not master this developmental task may experience stagnation with little connection to others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.[11]

- Integrity vs. Despair: The mid-60s to the end of life is a period of development known as late adulthood. People in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity and often look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” or “could have” been. They face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.[12]

Piaget's Theory of Development

Jean Piaget, a well-known cognitive development theorist, noted that children explore the world as they attempt to make sense of their experiences. His theory explains that humans move from one stage to another as they seek cognitive equilibrium and mental balance. There are four stages in Piaget’s theory of development that occur in children from all cultures:

- Sensorimotor: The first stage is the sensorimotor period. It extends from birth to approximately two years and is a period of rapid cognitive growth. During this period, infants develop an understanding of the world by coordinating sensory experiences (seeing, hearing) with motor actions (reaching, touching). The main development during the sensorimotor stage is the understanding that objects exist, and events occur in the world independently of one's own actions.[13] Infants develop an understanding of what they want and what they must do to have their needs met. They begin to understand language used by those around them to make needs met.

- Pre-Operational: Infants progress from the sensorimotor period to a pre-operational period in their toddler years that continues through early school age years. This is the time frame when children learn to think in images and symbols. Play is an important part of cognitive development during this period.

- Concrete Operations: Older school age children (age 7 years to 11 years) enter a concrete operations period. They learn to think in terms of processes and can understand that there is more than one perspective when discussing a concept.[14] This stage is considered a major turning point in the child's cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought.

- Formal Operations: Adolescents transition to the formal operations stage around age 12 as they become self-conscious and egocentric. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner by manipulating ideas in their head. Moving toward adulthood, this further develops into the ability to critically reason.[15],[16]

Cognitive Impairments in Children

Cognitive impairments in children range from mild impairment in these specific operations to profound intellectual impairments leading to minimal independent functioning. Cognitive impairment is a term used to describe impairment in mental processes that drive how an individual understands and acts in the world, affecting the acquisition of information and knowledge. The following areas are domains of cognitive functioning:

- Attention

- Decision-making

- General knowledge

- Judgment

- Language

- Memory

- Perception

- Planning

- Reasoning

- Visuospatial[17]

Intellectual disability (formerly referred to as mental retardation) is a diagnostic term that describes intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits identified during the developmental period. In the United States, the developmental period refers to the span of time prior to the age 18. Children with intellectual disabilities may demonstrate a delay in developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, speaking, walking) or demonstrate mild cognitive impairments that may not be identified until school age. Intellectual disability is typically nonprogressive and lifelong. It is diagnosed by multidisciplinary clinical assessments and standardized testing and is treated with a multidisciplinary treatment plan that maximizes quality of life.[18] See Figure 6.2[19] for an image of an adolescent with an intellectual disability participating in a Special Olympics event.

Cognitive Impairments in Adults and Older Adults

There are several physical changes that occur in the brain due to aging. The structure of neurons changes, including a decreased number and length of dendrites, loss of dendritic spines, a decrease in the number of axons, an increase in axons with segmental demyelination, and a significant loss of synapses. Loss of synapse is a key marker of aging in the nervous system. These physical changes occur in older adults experiencing cognitive impairments, as well as in those who do not.[20] See Figure 6.3[21] of an older adult experiencing typical physical changes of aging.

It is a common myth that all individuals experience cognitive impairments as they age. Many people are afraid of growing older because they fear becoming forgetful, confused, and incapable of managing their daily life leading to incorrect perceptions and ageism. Ageism refers to stereotyping older individuals because of their age. Losing language skills, becoming unable to make decisions appropriately, and being disoriented to self or surroundings are not normal aging changes.

Dementia, Delirium, and Depression

If cognitive changes in adults occur, a complete assessment is required to determine the underlying cause of the change and if it is caused by an acute or chronic condition. For example, dementia is a chronic condition that affects cognition whereas depression and delirium can cause acute confusion with a similar clinical appearance to dementia.

Dementia

Dementia is a chronic condition of impaired cognition, caused by brain disease or injury, and marked by personality changes, memory deficits, and impaired reasoning. Dementia can be caused by a group of conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, and Lewy body disease. Clinical manifestations of dementia include forgetfulness, impaired social skills, and impaired decision-making and thinking abilities that interfere with daily living. Dementia is gradual, progressive, and irreversible.[22] While dementia is not reversible, appropriate assessment and nursing care improve the safety and quality of life for those affected by dementia.

As dementia progresses and cognition continues to deteriorate, nursing care must be individualized to meet the needs of the client and family. Providing client safety and maintaining quality of life while meeting physical and psychosocial needs are important aspects of nursing care. Unsafe behaviors put individuals with dementia at increased risk for injury. These unsafe or inappropriate behaviors often occur due to the client having a need or emotion without the ability to express it, such as pain, hunger, anxiety, or the need to use the bathroom. The client’s family/caregivers require education and support to recognize that behaviors are often a symptom of dementia and/or a communication of a need and to help them to best meet the needs of their family member.[23]

Delirium

Delirium is an acute state of cognitive impairment that typically occurs suddenly due to a physiological cause, such as infection, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances, drug effects, or other acute brain injury. Sensory overload, excess stress, and sleep deprivation can also cause delirium. Hospitalized older adults are at increased risk for developing delirium, especially if they have been previously diagnosed with dementia. One third of clients aged 70 years or older exhibit delirium during their hospitalization. Delirium is the most common surgical complication for older adults, occurring in 15 to 25% of clients after major elective surgery and up to 50% of clients experiencing hip-fracture repair or cardiac surgery.[24]

The symptoms of delirium usually start suddenly, over a few hours or a few days, and they often come and go. Common symptoms include the following:

- Changes in alertness (usually most alert in the morning and decreased at night)

- Changing levels of consciousness

- Confusion

- Disorganized thinking or talking in a way that does not make sense

- Disrupted sleep patterns or sleepiness

- Emotional changes: anger, agitation, depression, irritability, overexcitement

- Hallucinations and delusions

- Incontinence

- Memory problems, especially with short-term memory

- Trouble concentrating[25]

Delirium and dementia have similar symptoms, so it can be hard to tell them apart. They can also occur together.

Nurses must closely monitor the cognitive function of all clients and promptly report any changes in mental status to the health care provider. The provider will take a medical history, perform a physical and neurological examination, perform mental status testing, and may order diagnostic tests based on the client’s medical history. After the cause of delirium is determined, treatment is targeted to the cause to reverse the effects. See Figure 6.4[26] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing delirium.

General interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older adults are as follows:

- Control the environment. Make sure that the room is quiet and well-lit, have clocks or calendars in view to provide time orientation, and encourage family members to visit.

- Ensure a safe environment with the call light within reach and side rails up as indicated.

- Administer prescribed medications, including those that control aggression or agitation, and pain relievers if there is pain.

- Ensure the client has their glasses, hearing aids, or other assistive devices for communication in place. Lack of assistive sensory devices can worsen delirium.

- Avoid sedatives. Sedatives can worsen delirium.

- Assign the same staff for client care when possible.[28]

Depression

Depression is a brain disorder with a variety of causes, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. It is a commonly untreated condition in older adults and can result in impaired cognition and difficulty in making decisions. It is likely to occur in response to major life events involving health and loved ones. Having other chronic health problems, such as diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease, increases the likelihood for depression in older adults and can cause the loss of their ability to maintain independence.[29] See Figure 6.5[30] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing symptoms of depression.

Symptoms of depression include the following:

- Feeling sad or "empty"

- Loss of interest in favorite activities

- Overeating or not wanting to eat at all

- Not being able to sleep or sleeping too much

- Feeling very tired

- Feeling hopeless, irritable, anxious, or guilty

- Aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems

- Thoughts of death or suicide[31]

Depression is treatable with medication and psychotherapy. However, older adults have an increased risk for suicide, with the suicide rates for individuals over age 85 years the second highest rate overall. Nurses should provide appropriate screening to detect potential signs of depression as an important part of promoting health for older adults.

Comparison of Three Conditions

When an older adult presents with confusion, determining if it is caused by delirium, dementia, depression, or a combination of these conditions can pose many challenges to the health care team. It is helpful to know the client’s baseline mental status from a family member, caregiver, or previous health care records. If a client’s baseline mental status is not known, it is an important safety consideration to assume that confusion is caused by delirium with a thorough assessment for underlying causes.[32] See Table 6.2 for a comparison of symptoms of dementia, delirium, and depression.[33]

Table 6.2 Comparison of Dementia, Delirium, and Depression[34]

| Dementia | Delirium | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Vague, insidious onset; symptoms progress slowly | Sudden onset over hours and days with fluctuations | Onset often rapid with identifiable trigger or life event such as bereavement |

| Symptoms | Symptoms may go unnoticed for years. May attempt to hide cognitive problems or may be unaware of them. Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening (referred to as "sundowning") | Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory loss and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening | Obvious at early stages and often worse in the morning. Can include subjective complaints of memory loss |

| Consciousness | Normal | Impaired attention/alertness | Normal |

| Mental State | Possibly labile mood. Consistently decreased cognitive performance | Emotional lability with anxiety, fear, depression, aggression. Variable cognitive performance | Distressed/unhappy. Variable cognitive performance |

| Delusions/Hallucinations | Common | Common | Rare |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | Psychomotor disturbance in later stages | Psychomotor disturbance present - hyperactive, purposeless, or apathetic | Slowed psychomotor status in severe depression |