Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Preventing medication errors has been a key target for improving safety since the 1990s. Despite error reduction strategies, implementing new technologies, and streamlining processes, medication errors remain a significant concern with error rates of 8%-25% during medication administration.[1] Furthermore, a substantial proportion of errors occur in hospitalized children due to the complexity of weight-based pediatric dosing.[2]

Several prevention initiatives have been developed to ensure safe medication administration such as the following strategies[3]:

- Routinely checking the rights of medication administration

- Standardizing communication such as “tall man lettering,” alerts to “look alike-sound alike” drug names, avoidance of abbreviations, and standards for expressing numerical dosages

- Focusing on high-alert medications that have a higher likelihood of resulting in patient harm if involved in an administration error, such as anticoagulants, insulins, opioids, and chemotherapy agents

- Standardizing labelling of medication using visual cues as safeguards

- Optimizing nursing workflow to minimize errors, such as minimizing interruptions and double checking high alert medications

- Implementing technology like barcode medication administration and smart infusion pumps

Read the article “Medication Administration Errors” on the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) website.[4]

The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals related to mediation administration were previously discussed in the “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration” section of this chapter. This section will further discuss additional safety initiatives established by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), World Health Organization (WHO), Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), and Quality and Safe Education for Nurses (QSEN) to prevent medication errors.

Institute of Medicine

To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System Report

The national focus on reducing medical errors has been in place since the 1990s. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a historic report in 1999 titled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The report stated that errors caused between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths every year in American hospitals and over one million injuries. The IOM report called for a 50% reduction in medical errors over five years. Its goal was to break the cycle of inaction regarding medical errors by advocating for a comprehensive approach to improving patient safety. The IOM 1999 report changed the focus of patient safety from dispensing blame to improving systems.[5]

Preventing Medication Errors Report

In 2007 the IOM published a follow-up report titled Preventing Medication Errors, reporting that more than 1.5 million Americans are injured every year in American hospitals, and the average hospitalized client experiences at least one medication error each day. This report emphasized actions that health care systems, providers, funders, and regulators could take to improve medication safety. These recommendations included actions such as having all U.S. prescriptions written and dispensed electronically, promoting widespread use of medication reconciliation, and performing additional research on drug errors and their prevention. The report also emphasized actions that client can take to prevent medication errors, such as maintaining active medication lists and bringing their medications to appointments for review.[6]

The Preventing Medication Errors report included specific actions for nurses to improve medication safety. The box below summarizes key actions.[7]

Improving Medication Safety: Actions for Nurses

- Establish safe work environments for medication preparation, administration, and documentation; for instance, reduce distractions and provide appropriate lighting.

- Maintain a culture of rigorous commitment to principles of safety in medication administration (for example, consistently checking the rights of medication administration and also performing double checks with colleagues as recommended).

- Remove barriers and facilitate the involvement of client surrogates in checking the administration and monitoring the medication effects.

- Foster a commitment to clients’ rights as co-consumers of their care.

- Develop aids for clients or their surrogates to support self-management of medications.

- Enhance communication skills and team training to be prepared and confident in questioning medication orders and evaluating client responses to drugs.

- Actively advocate for the development, testing, and safe implementation of electronic health records.

- Work to improve systems that address “near misses” in the work environment.

- Realize they are part of a system and do their part to evaluate the efficacy of new safety systems and technology.

- Contribute to the development and implementation of error reporting systems and support a culture that values accurate reporting of medication errors.

World Health Organization: Medication Without Harm

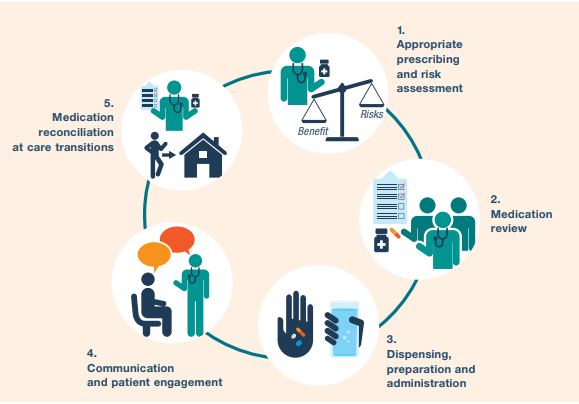

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified “Medication Without Harm” as the theme for the third Global Patient Safety Challenge with the goal of reducing severe, avoidable medication-related harm by 50% over the next five years. As part of the Global Patient Safety Challenge: Medication Without Harm, the WHO has prioritized three areas to protect clients from harm while maximizing the benefit from medication[8]:

- Medication safety in high-risk situations

- Medication safety in polypharmacy

- Medication safety in transitions of care

Read more information about the WHO initiative called Medication Without Harm.

View the follow YouTube video explaining how to avoid harm from medications.

Medication Without Harm[9]

A summary of strategies to reduce harm and ensure medication safety is provided in Figure 2.3.[10]

Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations

The first priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative, medication safety in high-risk situations, includes the components of high-risk medications, provider-client relations, and systems factors.

High-Risk (High-Alert) Medications

High-risk medications are drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant client harm when they are used in error.[11]

High-risk medication can be remembered using the mnemonic “A PINCH.” The information in the box below describes these medications included with the “A PINCH” mnemonic.

High-Risk Medication Group Examples of Medication

A: Anti-infective Amphotericin, aminoglycosides

P: Potassium & other electrolytes Injections of potassium & other electrolytes

I: Insulin All types of insulin

N: Narcotics & other sedatives Opioids, such as morphine; Benzodiazepines

C: Chemotherapeutic agents Methotrexate and vincristine

H: Heparin & anticoagulants Warfarin and enoxaparin

Note: Based on research, the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has expanded this list of high-risk medications. The updated list can be viewed in the box below.

Strategies for safe administration of high-alert medication include the following:

- Standardizing the ordering, storage, preparation, and administration of these products

- Improving access to information about these drugs

- Employing clinical decision support and automated alerts

- Using redundancies such as automated or independent double-checks when necessary

Provider-Patient Relations

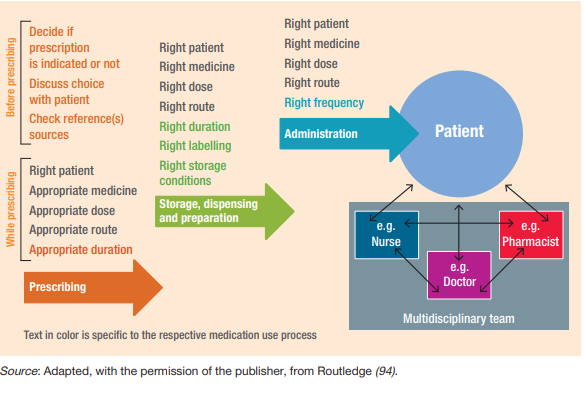

In addition to high-risk medications, a second component of medication safety in high-risk situations includes provider and client factors. This component relates to either the health care professional providing care or the client being treated. Even the most dedicated health care professional is fallible and can make errors. The act of prescribing, dispensing, and administering a medicine is complex and involves several health care professionals. The client should be the center of what should be a “prescribing partnership.”[12] See Figure 2.4 for an illustration of the prescribing partnership.[13]

Life Span Considerations

Other risk factors can exist in specific clients across the life span. For example, adverse drug events occur most often at the extremes of life (in the very young and very old). In the older adult population, frail clients are likely to receive several medications concurrently, which adds to the risk of adverse drug events. In addition, the harm of some of these medication combinations may be synergistic, meaning the risk is greater when medications are taken together than the sum of the risks of individual agents. In neonates (particularly premature neonates), elimination routes through the kidney or liver may not be fully developed. The very young and very old are also less likely to tolerate adverse drug reactions, either because their homeostatic mechanisms are not yet fully developed, or they may have deteriorated. Medication errors in children, where doses may have to be calculated in relation to body weight or age, are also a source of major concern. Additionally, certain medical conditions predispose clients to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions, particularly renal or hepatic dysfunction and cardiac failure. Interprofessional strategies to address these potential harms are based on a systems approach with a “prescribing partnership” between the client, the prescriber, the pharmacist, and the nurse that includes verifying orders when concerns exist.

Systems Factors

In addition to high-risk medications and provider-patient relations, systems factors also contribute to medication safety in high-risk situations. Systems factors can contribute to error-provoking conditions for several reasons. The unit may be busy or understaffed, which can contribute to inadequate supervision or failure to remember to check important information. Interruptions during critical processes (e.g., administration of medicines) can also occur, which can have significant implications for patient safety. Tiredness and the need to multitask when busy or flustered can also contribute to error and can be compounded by poor electronic medical record design. Preparing and administering intravenous medications are also particularly error prone. Strategies for reducing errors include checking at each step of the medication administration process; preventing interruptions; using electronic provider order entry; and utilizing prescribing assessment tools, such as the Beers Criteria, to evaluate for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults.[14] The Beers Criteria is a list of potentially harmful medications or medications with side effects that outweigh the benefit of taking the medication.

Read additional information about the updated Beers Criteria by the American Geriatrics Society.

Medication Safety in Polypharmacy

The second priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety in polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is the concurrent use of multiple medications. Although there is no standard definition, polypharmacy is often defined as the routine use of five or more medications including over-the-counter, prescription, and complementary medicines.

As people age, they are more likely to suffer from multiple chronic illnesses and take multiple medications. It is essential to use a person-centered approach to ensure their medications are appropriate to gain the most benefits without harm and to ensure the client is part of the decision-making process. Appropriate polypharmacy is present when all medicines are prescribed for the purpose of achieving specific therapeutic objectives that have been agreed with the client; therapeutic objectives are actually being achieved or there is a reasonable chance they will be achieved in the future; medication therapy has been optimized to minimize the risk of adverse drug reactions; and the client is motivated and able to take all medicines as intended.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is present when one or more medications are prescribed that are no longer needed. One or more medications may no longer be needed because there is no evidence-based indication, the indication has expired or the dose is unnecessarily high, they fail to achieve the therapeutic objectives they were intended to achieve, one or the combination of several medications put the client at a high risk of adverse drug reactions, or the client is not willing or able to take the medications as intended.[15]

When clients transition across health care settings, medication review by nurses is essential to prevent harm caused by inappropriate polypharmacy. [16]

Review questions to address during a medication review in Chapter 2 of WHO’s Medication Safety in Polypharmacy Technical Report.[17]

Medication Safety in Transitions of Care

The third priority of the WHO Medications Without Harm initiative relates to medication safety during transitions of care. View the interactive activity below to see how medications are reconciled during transitions of care from admission to discharge in a hospital setting.

Interactive Activity

“Medication Reconciliation Process” by E. Christman for Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0

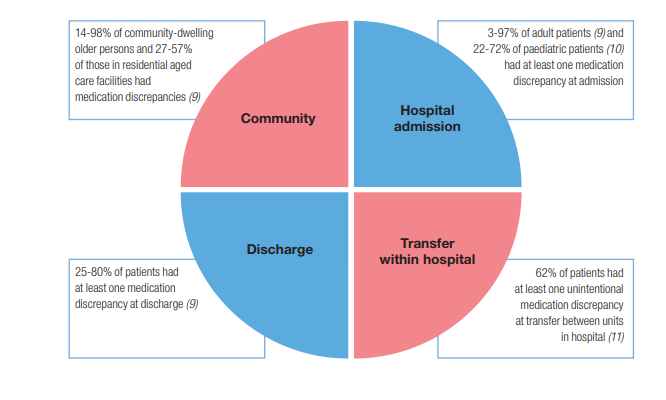

Medication errors can occur during transitions across settings. Figure 2.5[18] is an image from the World Health Organization showing ranges of percentage of errors that occur during common transitions of care.

Key strategies for improving medication safety during transitions of care include the following:

- Implementing formal structured processes for medication reconciliation at all transition points of care. Steps of effective medication reconciliation are to build the best possible medication history by interviewing the client and verifying with at least one reliable information source, reconciling and updating the medication list, and communicating with the client and future health care providers about changes in their medications.

- Partnering with clients, families, caregivers, and health care professionals to agree on treatment plans, ensuring clients are equipped to manage their medications safely, and ensuring clients have an up-to-date medication list.

- Where necessary, prioritizing clients at high risk of medication-related harm for enhanced support such as post-discharge contact by a nurse.[19]

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5a

A nurse is performing medication reconciliation for an elderly client admitted from home. The client does not have a medication list and cannot report the names, dosages, and frequencies of the medication taken at home.

What other sources can the nurse use to obtain medication information?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Institute for Safe Medication Practices

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) is respected as the gold standard for medication safety information. It is a nonprofit organization devoted entirely to preventing medication errors. ISMP collects and analyzes thousands of medication error and adverse event reports each year through its voluntary reporting program and then issues alerts regarding errors happening across the nation. The ISMP has established several prevention strategies for safe medication administration, including lists of high-alert medications, error-prone abbreviations to avoid, do not crush medications, look-alike and sound-alike drugs, and error-prone conditions that lead to error by nurses and student nurses. Each of these initiatives is further described below.[20]

Error-Prone Abbreviations

ISMP’s List of Error-Prone Abbreviations, Symbols, and Dose Designations contains abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations that have been reported through the ISMP National Medication Errors Reporting Program as being frequently misinterpreted and involved in harmful medication errors. These abbreviations, symbols, and dose designations should never be used when communicating medical information. Note that this list has additional abbreviations than those contained in The Joint Commission’s Do Not Use List of Abbreviations. Review the information below for the ISMP list of error-prone abbreviations to avoid. Some examples of abbreviations that were commonly used that should now be avoided are qd, qod, qhs, BID, QID, D/C, subq, and APAP.[21]

Strategies to avoid mistakes related to error-prone abbreviations include not using these abbreviations in medical documentation. Furthermore, if a nurse receives a prescription containing an error-prone abbreviation, it should be clarified with the provider and the order rewritten without the abbreviation.

Download the ISMP List of Error-Prone Abbreviations to Avoid PDF.

Do Not Crush List

The IMSP maintains a list of oral dosage medication that should not be crushed, commonly referred to as the “Do Not Crush” list. These medications are typically extended-release formulations.[22] Strategies for preventing harm related to oral medication that should not be crushed include requesting an order for a liquid form or a different route if the client cannot safely swallow the pill form.

Look-Alike and Sound-Alike (LASA) Drugs

ISMP maintains a list of drug names containing look-alike and sound-alike name pairs such as Adderall and Inderal. These medications require special safeguards to reduce the risk of errors and minimize harm.

Safeguards may include the following:

- Using both the brand and generic names on prescriptions and labels

- Including the purpose of the medication on prescriptions

- Changing the appearance of look-alike product names to draw attention to their dissimilarities

- Configuring computer selection screens to prevent look-alike names from appearing consecutively[23]

Download the ISMP’s List of Confused Drug Names PDF.

Error-Prone Conditions That Lead to Student Nurse Related Error

When analyzing errors involving student nurses reported to the USP-ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program and the PA Patient Safety Reporting System, it appears that many errors arise from a distinct set of error-prone conditions or medications. Some student-related errors are similar in origin to those that seasoned licensed health care professionals make, such as misinterpreting an abbreviation, misidentifying drugs due to look-alike labels and packages, misprogramming a pump due to a pump design flaw, or simply making a mental slip when distracted. Other errors stem from system problems and practice issues that are rather unique to environments where students and hospital staff are caring together for clients. View the list of error-prone conditions that should be avoided using the following box.

Critical Thinking Activity 2.5b

A nurse is preparing to administer insulin to a client. The nurse is aware that insulin is a medication on the ISMP list of high-alert medications.

What strategies should the nurse implement to ensure safe administration of this medication to the client?

Note: Answers to the Critical Thinking activities can be found in the “Answer Key” section at the end of the book.

Quality and Safety Education for Nurses

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project’s vision is to “inspire health care professionals to put quality and safety as core values to guide their work.” QSEN began in 2005 and is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Based on the Institute of Medicine (2003) competencies for nursing, QSEN further defined these quality and safety competencies for educating nursing students:

- Patient-Centered Care

- Teamwork & Collaboration

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Quality Improvement

- Safety

- Informatics[24]

View the QSEN website.

Below are supplementary QSEN learning resources related to patient safety and preventing errors during medication administration.

The Josie King Story and Medical Errors[25]

Summary of Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

Medication administration by nurses is not just a task on a daily task list; it is a system-wide process in collaboration with other health care team members to ensure safe and effective treatment. As part of the medication administration process, the nurse must consider ethics, laws, national guidelines, and cultural/social determinants before administering medication to a client. The nurse is the vital “last stop” for preventing errors and potential harm from medications before they reach the client. A list of nursing considerations whenever administering medications is outlined below.

Nursing Considerations for Safe and Effective Medication Administration

BEFORE Administering Medication

Ethics

- Will this medication do more good than harm for this client at this point in time?

- Has the client (or the client’s decision maker) had a voice in the decision-making process regarding use of this medication? Have they been informed about this medication and the potential risks/benefits to consider?

- If there are any ethical concerns, advocate for client rights and autonomy and contact the provider and/or pursue the proper chain of command.

Laws and National Guidelines

- Be sure the prescription/order contains the proper information according to CMS guidelines.

- Are there any FDA Boxed Warnings for this drug? If so, is the client aware of the risks and what to do if they occur? This discussion should be documented.

- Is this a controlled substance? If so, follow guidelines and agency policy for controlled substances in terms of counting, wasting, and disposal. For prescriptions for outpatient use, advocate that Prescription Drug Monitoring Program guidelines are followed.

- Be aware of signs of drug diversion in other health care team members and follow up appropriately in the chain of command. You can also directly submit an online tip to the DEA at Rx Abuse Online Reporting.

- Follow the Joint Commission “SPEAK UP” guidelines if you have any concerns about the safe use of this medication, including, but not limited to:

- Unclear or “do not use” abbreviations

- Strategies for look alike-sound alike medications

- Any other concerns for error

- Follow your state’s practice act regarding Scope of Practice and Rules of Conduct. Is administering this medication appropriate for your scope of practice and for this client? If not, protect your client from harm and your nursing license by notifying the appropriate contacts within your agency.

- Is this medication administration occurring during a transition of care from unit to unit, home to agency, or in preparation for discharge? If so, be sure proper medication reconciliation has been completed.

DURING Administration

- Use the nursing process as you ASSESS if this drug is appropriate to administer at this time and PLAN continued monitoring. Consider life span and disease process implications. If you NOTICE any findings that this medication may not be appropriate at this time for this client, withhold the medication and contact the provider.

- Assess if there are any cultural or social determinants that will impact the client’s ability to use these medications safely and effectively. IMPLEMENT appropriate accommodations as needed and notify the provider.

- Follow The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals as you correctly identify the client and follow guidelines to use medicines safely.

- If this is a high-alert medication, follow recommendations for safe administration (such as adding a second RN check, etc.).

- Reduce distractions in your environment as you prepare and administer medications.

- Do not crush medications unless safe to do so.

- Follow standards set by The Joint Commission and CMS:

- Checking rights of medication administration before administering any medication to a client

- Educate the client about their medication

- Dispose of unused controlled substances appropriately

- Document appropriately

AFTER Administration

- Continue to EVALUATE the client for potential side effects/adverse effects, as well as therapeutic effects of the medications.

- Document and verbally share your findings during handoff reports for safe continuity of care.

- If an error occurs, file an incident report and participate in root cause analysis to determine how to prevent it from happening again.

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- MacDowell, P., Cabri, A., & Davis, M. (2021). Medication administration errors. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer/medication-administration-errors ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728 ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623 ↵

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Medication without harm. https://www.who.int/initiatives/medication-without-harm ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017, October 17). WHO: Medication without harm [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/MWUM7LIXDeA ↵

- This image is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325131 page 7, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2018). ISMP List of High-Alert Medications for Acute Care Settings. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-08/highAlert2018-Acute-Final.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This image is a derivative of (2019) Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325131 page 24, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in High-Risk Situations by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Medication Safety in Polypharmacy by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of (2019) Medication Safety in Transition of Care by World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325453/WHO-UHC-SDS-2019.9-eng.pdf?ua=1 page 15, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- This image is a derivative of Medication Safety in Transition of Care by World Health Organization licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2007, October 18). Error-prone conditions that lead to student nurse-related errors. https://www.ismp.org/resources/error-prone-conditions-lead-student-nurse-related-errors ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2017, October 2). List of error-prone abbreviations. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/error-prone-abbreviations-list ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2020, February 21). Oral dosage forms that should not be crushed. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/do-not-crush ↵

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. (2019, February 28). List of confused drug names. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list ↵

- QSEN Institute. (n.d.). Project overview. http://qsen.org/about-qsen/project-overview/ ↵

- Healthcare.gov. (2011, May 25). Introducing the partnerships for patients with Sorrel King [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ak_5X66V5Ms ↵

Before every patient interaction, the nurse must perform hand hygiene and consider the use of additional personal protective equipment, introduce themselves, and identify the patient using two different identifiers. It is also important to provide a culturally safe space for interaction and to consider the developmental stage of the patient.

Hand Hygiene and Infection Prevention

Before initiating care with a patient, hand hygiene is required, and a risk assessment should be performed to determine the need for personal protective equipment (PPE). This is important for protection of both patient and nurse.

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is a simple but effective way to prevent infection when performed correctly and at the appropriate times when providing patient care. See Figure 1.3.[1] for an image about hand hygiene from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).[2] Use the information below to learn more and watch a video about effective handwashing.

Key points from the CDC about hand hygiene include the following[3]:

- In general, hand sanitizers are as effective as washing with soap and water and are less drying to the skin. When using hand sanitizer, use enough gel to cover both hands and rub for approximately 20 seconds, coating all surfaces of both hands until your hands feel dry. Go directly to the patient without putting your hands into pockets or touching anything else.[4]

- Be sure to wash with soap and water if your hands are visibly soiled or the patient has diarrhea from suspected or confirmed C. Difficile (C-diff).

- Clean all areas of the hands, including the front and back, the fingertips, the thumbs, and between fingers.

- Gloves are not a substitute for cleaning your hands. Wash your hands after removing gloves.

- Hand hygiene should be performed at these times:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task (e.g., placing an indwelling device) or handling invasive medical devices

- Before moving from working on a soiled body site to a clean body site on the same patient

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces

- Before donning gloves and immediately after glove removal

- When leaving the area after touching a patient or their immediate environment

Checklists for performing handwashing and using hand sanitizer are located in Appendix A.

Visit the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's website to read more about Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings.

Download a PDF factsheet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called Clean Hands Count.

View supplementary videos on hand hygiene:

Clean Hands Count on YouTube[5]

Hand Washing Technique on YouTube[6]

Hand Sanitizing Technique on YouTube[7]

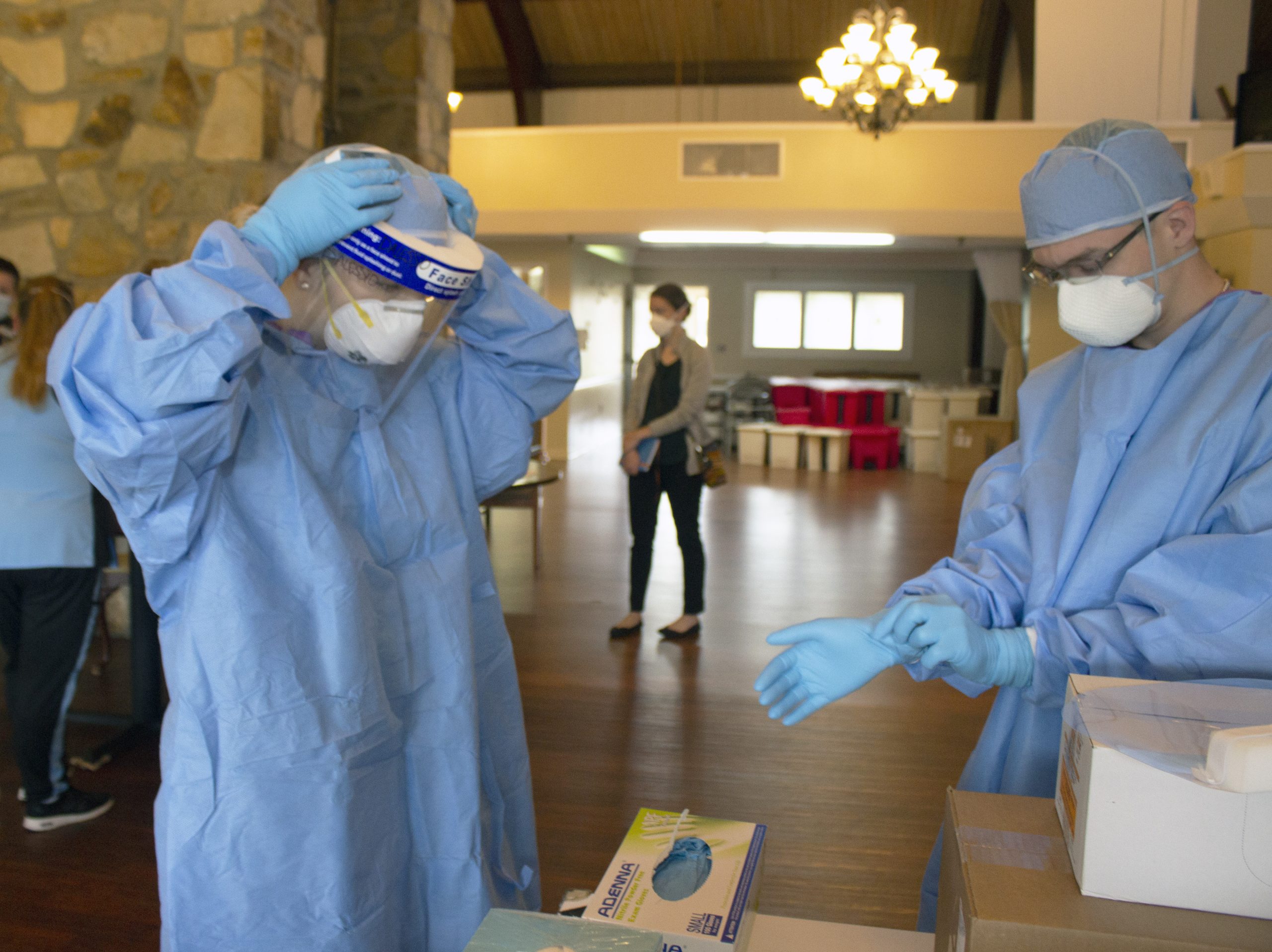

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Medical asepsis is a term used to describe measures to prevent the spread of infection in health care agencies. Performing hand hygiene at appropriate times during patient care and applying gloves when there is potential risk for exposure to body fluids are examples of using medical asepsis. Additional precautions are implemented by health care team members when a patient has, or is suspected of having, an infectious disease. These additional precautions are called personal protective equipment (PPE) and are based on how an infection is transmitted, such as by contact, droplet, or airborne routes. Personal protective equipment (PPE) includes gowns, eyewear or goggles, face shields, gloves, and masks. PPE is used along with environmental controls, such as surface cleaning and disinfecting to prevent the transmission of infection.[8] See Figure 1.4[9] for an image of health care team members applying PPE. These precautions are further discussed in the “Aseptic Technique” chapter. For the purpose of this chapter, be sure to perform a general risk assessment before entering a patient’s room and apply the appropriate PPE as needed. This risk assessment includes the following:

- Is there signage posted on the patient’s door that contact, droplet, enhanced barrier, or airborne precautions are in place? If so, follow the instructions provided.

- Does this patient have a confirmed or suspected infection or communicable disease?

- Will your face, hands, skin, mucous membranes, or clothing be potentially exposed to blood or body fluids by spray, coughing, or sneezing?

Introducing Oneself

When initiating care with patients, it is essential to first provide privacy, and then introduce yourself and explain what will be occurring. Providing privacy means taking actions such as talking with the patient privately in a room with the door shut or privacy curtain drawn around the bed. A common framework used to communicate with patients is AIDET, a mnemonic for Acknowledge, Introduce, Duration, Explanation, and Thank You.[10]

- Acknowledge: Greet the patient by the name documented in their medical record. Make eye contact, smile, and acknowledge any family or friends in the room. Ask the patient their preferred way of being addressed (for example, "Mr. Doe," "Jonathon," or "Johnny") and their preferred pronouns (i.e., he/him, she/her, or they/them), as appropriate.

- Introduce: Introduce yourself by your name and role. For example, “I’m John Doe and I am a nursing student working with your nurse to take care of you today.”

- Duration: Estimate a timeline for how long it will take to complete the task you are doing. For example, “I am here to obtain your blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation levels. This should take about 5 minutes.”

- Explanation: Explain step by step what to expect next and answer questions. For example, “I will be putting this blood pressure cuff on your arm and inflating it. It will feel as if it is squeezing your arm for a few moments.”

- Thank You: At the end of the encounter, thank the patient and ask if anything is needed before you leave. In an acute or long-term care setting, ensure the call light is within reach and the patient knows how to use it. If family members are present, thank them for being there to support the patient as appropriate. For example, “Thank you for taking time to talk with me today. Is there anything I can get for you before I leave the room? Here is the call light (Place within reach). Press the red button if you would like to call the nurse.”

For more information about AIDET, visit AIDET Patient Communication.

Patient Identification

Use at least two patient identifiers before performing assessments, obtaining vital signs, or providing care.

Use two patient identifiers:

- Ask the patient to state their name and date of birth. If they have an armband, compare the information they are stating to the information on the armband and verify they match. See Figure 1.5[11] for an image of an armband.

- If the patient doesn’t have an armband, confirm the information they are stating to information provided in the chart.

- If the patient is unable to state their name and date of birth, scan their armband or ask another staff member or family member to identify them.

Confirm "two identifiers" with a second source:

- Scan the wristband.

- Compare the name and date of birth to the patient’s chart.

- Ask staff to verify the patient in a long-term care setting.

- Compare the picture on the medication administration record (MAR) to the patient.

- If present, ask a family member to confirm the patient’s name.

Cultural Safety

When initiating patient interaction, it is important to establish cultural safety. Cultural safety refers to the creation of safe spaces for patients to interact with health professionals without judgment or discrimination. See Figure 1.6[12] for an image representing cultural safety. Recognizing that you and all patients bring a cultural context to interactions in a health care setting is helpful when creating cultural safe spaces. If you discover you need more information about a patient’s cultural beliefs to tailor your care, use an open-ended question that allows the patient to share what they believe to be important. For example, you may ask, “I am interested in your cultural background as it relates to your health. Can you share with me what is important about your cultural background that will help me care for you?”[13]

For more information about caring for diverse patients, visit the "Diverse Patients" chapter in the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook.

Adapting to Variations Across the Life Span

It is important to adapt your interactions with patients in accordance with their developmental stage. Developmentalists break the life span into nine stages[14]:

- Prenatal Development

- Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Early Childhood

- Middle Childhood

- Adolescence

- Early Adulthood

- Middle Adulthood

- Late Adulthood

- Death and Dying

A brief overview of the characteristics of each stage of human development is provided in Table 1.2. When caring for infants, toddlers, children, and adolescents, parents or guardians are an important source of information, and family dynamics should be included as part of the general survey assessment. When caring for older adults or those who are dying, other family members may be important to include in the general survey assessment. See Figure 1.7[15] for an image representing patients in various developmental stages of life.

Visit the Human Development Life Span e-book at LibreTexts to read additional information about human development across the life span.

Table 1.2 Variations Across the Life Span

| Stage of Development | Common Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Prenatal Development | Conception occurs, and development begins. All major structures of the body are forming, and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns for the mother. |

| Infancy and Toddlerhood | The first year and a half to two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child. |

| Early Childhood | Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years, consisting of the years that follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three- to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly however, and preschoolers may have initially interesting conceptions of size, time, space, and distance, such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for doing something that brings the disapproval of others. |

| Middle Childhood | The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood, and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Their world becomes filled with learning and testing new academic skills, assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments, and making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down, and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. Children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students. |

| Adolescence | The World Health Organization defines adolescence as a person between the age of 10 and 19. Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of injury from high-risk behaviors such as car accidents, drug and alcohol abuse, or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences or result in death. |

| Early Adulthood | The twenties and thirties are often thought of as early adulthood. It is a time of physiological peak but also highest risk for involvement in violent crimes and substance abuse. It is a time of focusing on the future and putting a lot of energy into making choices that will help one earn the status of a full adult in the eyes of others. Love and work are primary concerns at this stage of life. |

| Middle Adulthood | The late thirties through the mid-sixties is referred to as middle adulthood. This is a period in which aging processes that began earlier become more noticeable but also a time when many people are at their peak of productivity in love and work. It can also be a time of becoming more realistic about possibilities in life previously considered and of recognizing the difference between what is possible and what is likely to be achieved in their lifetime. |

| Late Adulthood | This period of the life span has increased over the last 100 years. For nurses, patients in this period are referred to as “older adults.” The term “young old” is used to describe people between 65 and 79, and the term “old old” is used for those who are 80 and older. One of the primary differences between these groups is that the young old are very similar to midlife adults because they are still working, still relatively healthy, and still interested in being productive and active. The “old old” may remain productive, active, and independent, but risks of heart disease, lung disease, cancer, and cerebral vascular disease (i.e., strokes) increase substantially for this age group. Issues of housing, health care, and extending active life expectancy are only a few of the topics of concern for this age group. A better way to appreciate the diversity of people in late adulthood is to go beyond chronological age and examine whether a person is experiencing optimal aging (when they are in very good health for their age and continue to have an active, stimulating life), normal aging (when the changes in health are similar to most of those of the same age), or impaired aging (when more physical challenges and diseases occur compared to others of the same age). |

| Death and Dying | Death is the final stage of life. Dying with dignity allows an individual to make choices about treatment, say goodbyes, and take care of final arrangements. When caring for patients who are actively dying, nurses can advocate for care that allows that person to die with dignity according to their wishes. |