Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and periwound skin

- Signs of infection

- Pain[1]

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

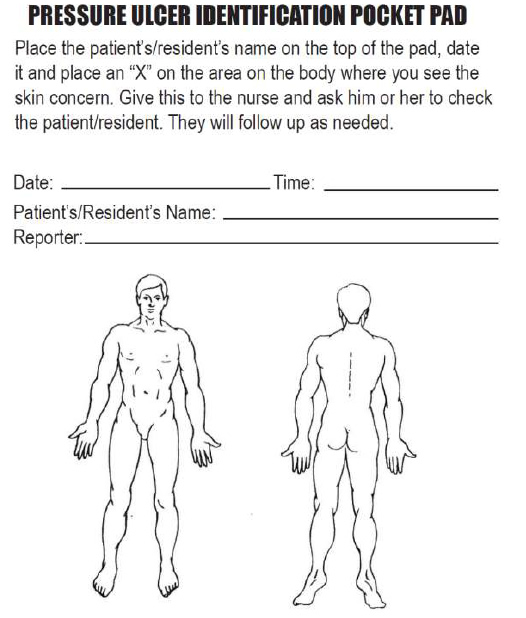

The location of the wound should be documented clearly using correct anatomical terms and numbering. This will ensure that if more than one wound is present, the correct one is being assessed and treated. Many agencies use images to facilitate communication regarding the location of wounds among the health care team. See Figure 20.16[2] for an example of facility documentation that includes images to indicate wound location.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Degree of Tissue Damage

It is important to continually assess the degree of tissue damage in pressure injuries because the level of damage can worsen if they are not treated appropriately. Refer to the “Staging” subsection of “Pressure Injuries” in the “Basic Concepts Related to Wounds” section for more information about tissue damage.

Wound Base

Assess the color of the wound base. Recall that healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing. Tunneling and undermining should also be assessed, documented, and communicated.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorized as scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms[3]:

- No exudate: The wound base is dry.

- Scant amount of exudate: The wound is moist, but no measurable amount of exudate appears on the dressing.

- Minimal amount of exudate: Exudate covers less than 25% of the size of the bandage.

- Moderate amount of drainage: Wound tissue is wet, and drainage covers 25% to 75% of the size of the bandage.

- Large or copious amount of drainage: Wound tissue is filled with fluid, and exudate covers more than 75% of the bandage.[4]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

- Sanguineous: Sanguineous exudate is fresh bleeding.[5]

- Serous: Serous drainage is clear, thin, watery plasma. It’s normal during the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and small amounts are considered normal wound drainage.[6]

- Serosanguinous: Serosanguineous exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.[7]

- Purulent: Purulent exudate is thick and opaque. It can be tan, yellow, green, or brown. It is never considered normal in a wound bed, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.[8] See Figure 20.17[9] for an image of purulent drainage.

Wound Size

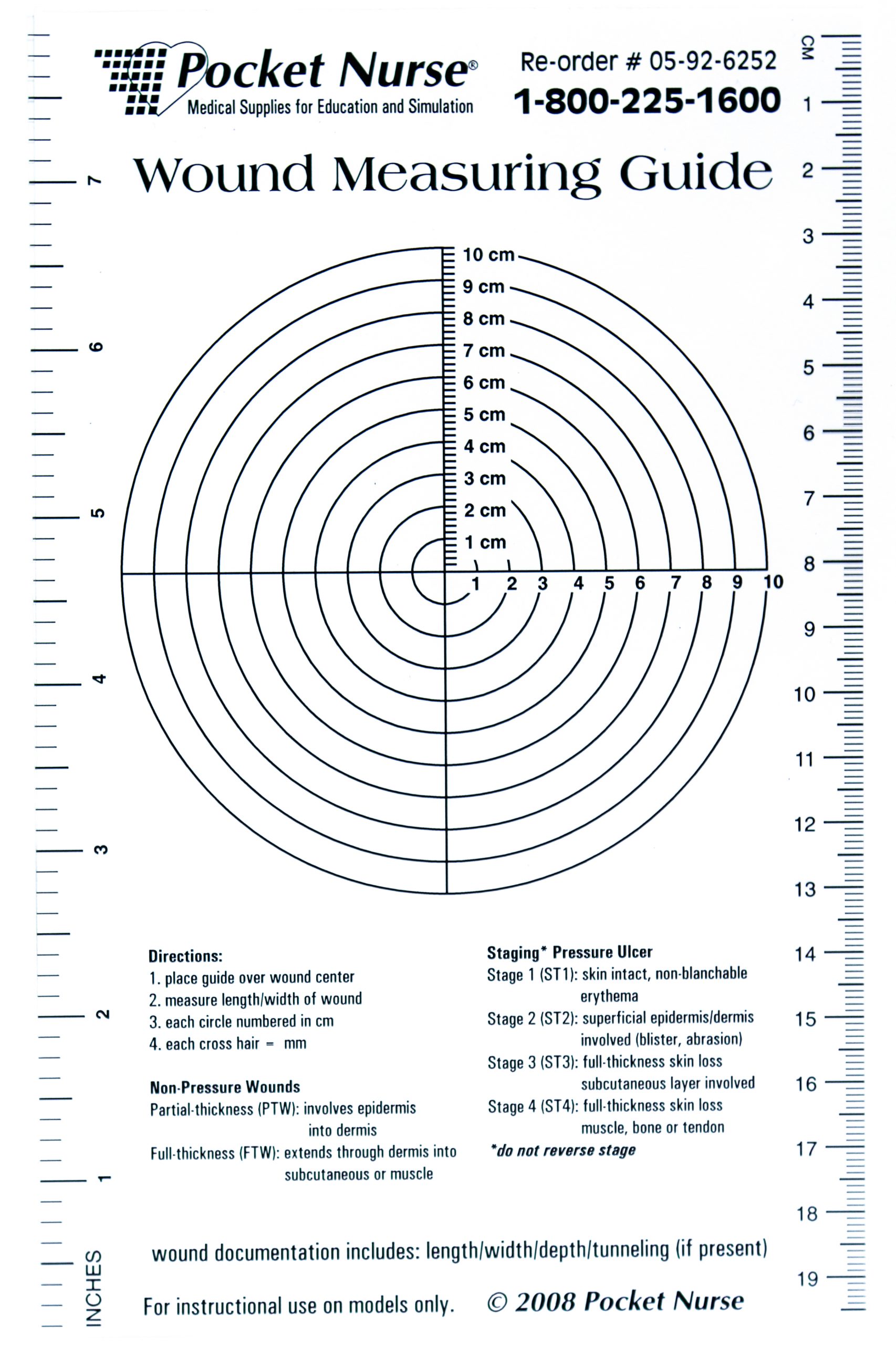

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how consistently to measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Many facilities use disposable, clear plastic measurement tools to measure the area of a wound healing by secondary intention. Measurements are typically documented in centimeters. See Figure 20.18[10] for an image of a wound measurement tool.

Tunneling can occur in a full-thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of a tunneling can be measured by gently probing the tunneled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.[11]

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound’s edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. Clock terms are also used to identify the area of undermining.[12]

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound, called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, a venous ulcer often has excess wound drainage that macerates the periwound skin, giving it a wet, waterlogged appearance that is soft and grayish white in color.[13] See Figure 20.19[14] for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localized wound infection include erythema (redness), induration (area of hardened tissue), pain, edema, purulent exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odor.[15] New signs of infection should be reported to the health care provider with an anticipated order for a wound culture.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.[16]

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- “putool7bfig.jpg” by unknown is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/settings/hospital/resource/pressureulcer/tool/pu7b.html ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- Wound Care Advisor. (n.d.). Exudate amounts. https://woundcareadvisor.com/exudate-amounts/#:~:text=Small%20or%20minimal%20amount%20of,than%2075%25%20of%20the%20bandage ↵

- “Purulant knee aspirate.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Sample Wound Measuring Guide.jpg” by Deanna Hoyord, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- WoundEducators.com. (2016, July 1). Wound undermining. https://woundeducators.com/measure-wound-undermining/#:~:text=Wound%20undermining%20occurs%20when%20the,surface%20until%20resistance%20is%20felt ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- “Post operative wound.JPG” by Intermedichbo is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

- Cox, J. (2019). Wound care 101. Nursing, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000580632.58318.08 ↵

Rigid device used to suction secretions from the mouth.

A soft, flexible, sterile catheter used for nasopharyngeal and tracheostomy suctioning.

A container for collecting suctioned secretions that is attached to a suction source.

Suction of secretions through the mouth, often using a Yankauer device.

A measurement of body size based on your height and weight.

Nurses access patients' veins to collect blood (i.e., perform phlebotomy) and to administer intravenous (IV) therapy. This section will describe several methods for collecting blood, as well as review the basic concepts of IV therapy.

Blood Collection

Nurses collect blood samples from patients using several methods, including venipuncture, capillary blood sampling, and blood draws from venous access devices. Blood may also be drawn from arteries by specially trained professionals for certain laboratory testing.

Venipuncture

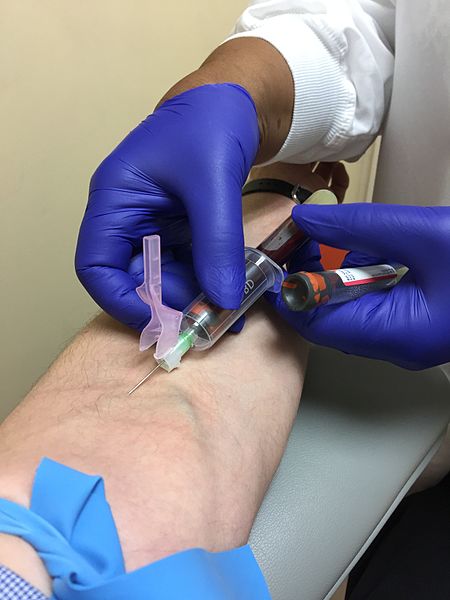

Venipuncture involves the process of introducing a needle into a patient’s vein to collect a blood sample or insert an IV catheter. See Figure 23.1[1] for an image of venipuncture. Blood sampling with venipuncture may be initiated by nurses, phlebotomists, or other trained personnel. Venipuncture for collection of a blood sample is an important part of data collection to assess a patient’s health status. It is commonly performed to examine hematologic and immune issues such as the body’s oxygen-carrying capacity, infection, and clotting function. It is also useful for assessing metabolic and nutrition issues such as electrolyte status and kidney functioning.

Blood collection is commonly performed via venipuncture from veins in the arms or hands. The most common sites for venipuncture are the large veins located on the antecubital fossa (i.e., the inner side of the elbow). These veins are often preferred for venipuncture because their larger size increases their ability to withstand repetitive blood sampling. However, these veins are not preferred for intravenous therapy due to the mechanical obstruction that can occur in the IV catheter when the elbow joint is contracted.

To perform the skill of venipuncture, the nurse performs many similar steps that occur with IV cannulation. The process of venipuncture for blood sample collection is outlined in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Perform Venipuncture Blood Draw" checklist.

Blood Samples From Central Venous Access Devices

Blood may also be collected by nurses from a patient's existing central venous access device (CVAD). A CVAD is a type of vascular access that involves the insertion of a catheter into a large vein in the arm, neck, chest, or groin.[2]

CVADs are discussed in more detail in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Manage Central Lines" chapter that also contains the "Obtain a Blood Sample From a CVAD" checklist.

Capillary Blood Sampling

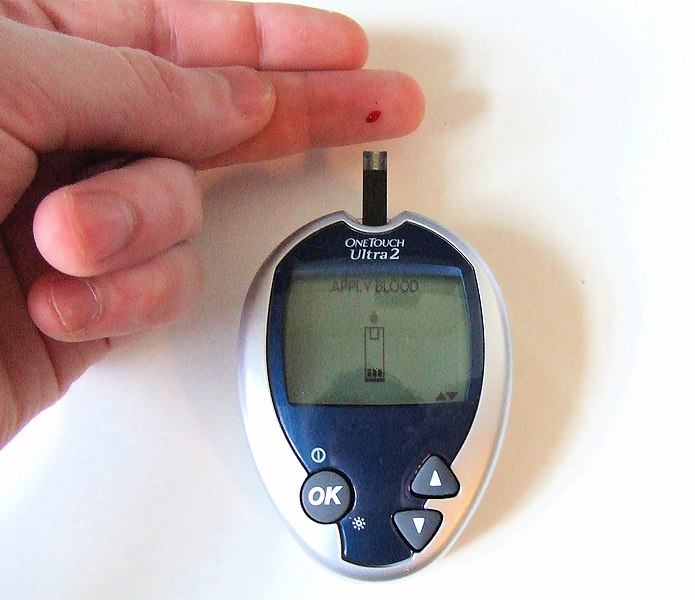

Nurses also collect small amounts of blood for testing via capillary blood sampling. Capillary blood testing occurs when blood is collected from capillaries located near the surface of the skin. Capillaries in the fingers are used for testing in adults whereas capillaries in the heels are used for infants. An example of capillary blood testing is bedside glucose testing. See Figure 23.2[3] for an image of capillary blood glucose testing.

Capillary blood testing is typically used when repetitive sampling is needed. However, not all blood tests can be performed on capillary blood, and some clinical conditions make capillary blood testing inappropriate, such as when a patient is hypotensive with limited venous return.

Review how to perform capillary blood glucose testing in the "Blood Glucose Monitoring" section of the "Specimen Collection" chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Arterial Blood Sampling

Arterial blood sampling occurs when blood is obtained via puncture into an artery by specially trained registered nurses and other health care personnel, such as respiratory therapists, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Arterial blood collection is most commonly performed to assess the body’s acid-base balance in a diagnostic test called an arterial blood gas. (For more information on arterial blood gas interpretation, please review Open RN Nursing Fundamentals Chapter 15). The most common access site for arterial blood sampling is the radial artery. See Figure 23.3[4] for an image of arterial blood sampling. Arterial blood tests are known to be more painful for the patient than venipuncture and have a higher risk of complications such as bleeding and arterial occlusion with subsequent ischemia to the area distal to the puncture.

Arterial Lines

For patients who require repetitive arterial blood sampling or are hemodynamically unstable, an arterial line may be inserted by specially trained personnel. Arterial lines are specialized tubes that are inserted and maintained in an artery to assist with continuous blood pressure monitoring. They also allow for repeated blood sampling without repetitive puncture, thus decreasing the amount of discomfort for the patient. The radial artery is the most common site used for arterial lines. Nurses must not confuse arterial lines with peripheral or central vein access devices. Arterial lines can be distinguished from venous lines by their specialized pressure tubing, which is firm and non-pliable and is connected to a pressure bag to maintain constant pressurized fluid in the tubing. Medications, fluid boluses, and maintenance IV fluids must never be infused through an arterial line. See Figure 23.3[5] for an image of arterial lines. The condition of the arterial access site, as well as perfusion of the patient's hand, is continually monitored when an arterial line is in place to prevent complications.

Intravenous Therapy

In addition to collecting blood samples, nurses also access patients' veins to administer intravenous therapy.Intravenous therapy (IV therapy) involves the administration of substances such as fluids, electrolytes, blood products, nutrition, or medications directly into a patient's vein. The intravenous route is preferred to administer fluids and medications when rapid onset of the medication or fluid is needed. The direct administration of medication into the bloodstream allows for a more rapid onset of medication actions, restoration of hydration, and correction of nutritional deficits. IV therapy is often used to restore fluids and/or resolve electrolyte imbalances more efficiently than what would be achieved via the oral route.

Fluid Balance

Fluid balance is an important part of optimal cellular functioning, and administration of fluids via the venous system provides an efficient way to quickly correct fluid imbalances. Additionally, many individuals who are physically unwell may not be able to tolerate fluids administered through their gastrointestinal tract, so IV administration is necessary. When administering IV therapy, the nurse needs to understand the nature of the solution being administered and how it will affect the patient's condition.

When patients experience deficient fluid volume, intravenous (IV) fluids are often used to restore fluid to the intravascular compartment or to facilitate the movement of fluid between compartments through the process of osmosis. There are three types of IV fluids: isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic.[6]

Review movement of fluid between compartments of the body in the "Basic Fluid and Electrolyte Concepts" section of the "Fluids and Electrolytes" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Isotonic Solutions

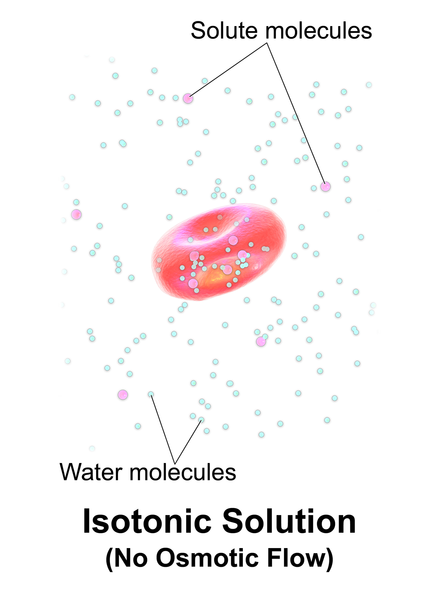

Isotonic solutions are IV fluids that have a similar concentration of dissolved particles as found in the blood. Examples of isotonic IV solutions are 0.9% normal saline (0.9% NaCl) or lactated ringers (LR). Because the concentration of isotonic IV fluid is similar to the concentration of blood, the fluid stays in the intravascular space, and osmosis does not cause fluid movement between cells. See Figure 23.4[7] for an illustration of isotonic IV solution administration that does not cause osmotic movement of fluid.

Isotonic solutions are used to treat fluid volume deficit (also called hypovolemia) to replace extracellular fluid that has been lost due to bleeding, dehydration, shock, burns, trauma, and gastrointestinal tract fluid loss (such as diarrhea). IV therapy with isotonic fluids will increase a patient's blood pressure. However, infusion of too much isotonic fluid can cause excessive fluid volume (also referred to as hypervolemia) and must be used with caution in patients with hypertension, heart failure, and renal disease due to the potential for fluid overload.[8]

Hypotonic Solutions

Hypotonic solutions have a lower concentration of dissolved solutes than blood. An example of a hypotonic IV solution is 0.45% normal saline (0.45% NaCl). Another example of hypotonic fluid is dextrose 5% in water (D5W). D5W is isotonic in the bag but becomes hypotonic after the dextrose is rapidly metabolized by the body.

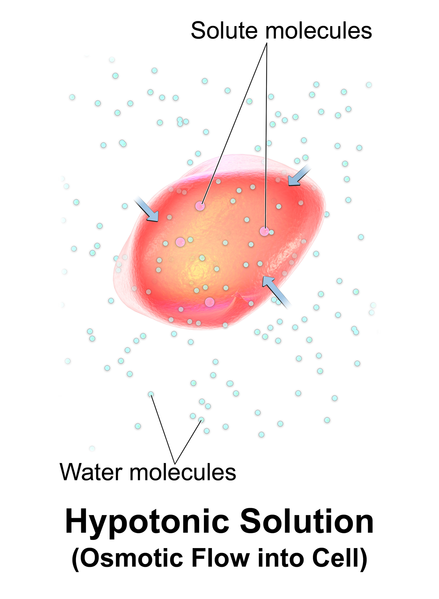

When hypotonic IV solutions are infused, it results in a decreased concentration of dissolved solutes in the blood as compared to the intracellular space. This imbalance causes osmotic movement of water from the intravascular compartment into the intracellular space. For this reason, hypotonic fluids are used to treat cellular dehydration. See Figure 23.5[9] for an illustration of the osmotic movement of fluid into a cell when a hypotonic IV solution is administered, causing lower concentration of solutes (pink molecules) in the bloodstream compared to within the cell.[10]

Hypotonic solutions are used for patients whose cells have become dehydrated, such as during diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or hyperosmolar hyperglycemia, and fluids must be pushed back into the cells. However, if too much fluid moves out of the intravascular compartment into the cells, cerebral edema, worsening hypovolemia, and hypotension can occur. Therefore, patient status should be monitored carefully when hypotonic solutions are infused.[11]

Hypertonic Solutions

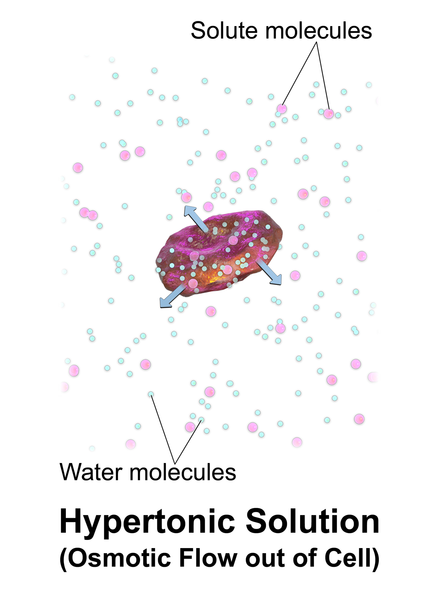

Hypertonic solutions have a higher concentration of dissolved particles than blood. An example of hypertonic IV solution is 3% normal saline (3% NaCl). When infused, hypertonic fluids cause an increased concentration of dissolved solutes in the intravascular space compared to the cells. This causes the osmotic movement of water out of the cells and into the intravascular space to dilute the solutes in the blood. See Figure 23.6[12] for an illustration of osmotic movement of fluid out of a cell when hypertonic IV fluid is administered due to a higher concentration of solutes (pink molecules) in the bloodstream compared to the cell.

Hypertonic solutions move water out of the cells of the body and into the bloodstream. They are commonly used for patients with cerebral edema, severe hyponatremia, or some types of post-op patients. Hypertonic solutions must be used very cautiously due to potentially rapid side effects of fluid overload resulting in pulmonary edema, so they are typically administered in intensive care units (ICU). Hypertonic fluids should not be administered to patients with DKA because it will worsen their cellular dehydration.

When administering hypertonic fluids, it is essential to monitor for signs of fluid overload, such as significantly elevated blood pressure and difficulties breathing. Additionally, if hypertonic solutions with sodium are given, the patient's serum sodium level should be closely monitored.[13]

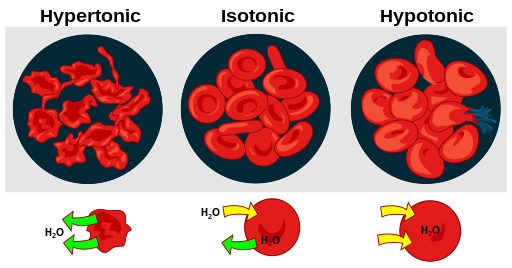

See Figure 23.7[14] for an illustration comparing how different types of IV solutions affect red blood cell size.

IV fluids are considered medications. As with all medications, nurses must check the rights of medication administration according to agency policy before administering IV fluids. What began as five rights of medication administration has been extended to eight rights according to the American Nurses Association. These eight rights include the following[15]:

- Right Patient

- Right Medication

- Right Dose

- Right Time

- Right Route

- Right Documentation

- Right Reason

- Right Response

Nurses also check for patient allergies, expiration date of the fluid, and compatibility of the fluid with any other fluids, medications, or blood products being administered intravenously. With any IV infusion, it is important for the nurse to pay close attention to the provider's order and make sure that it contains the specific type of fluid, any additives or medications, amount to be infused, rate of infusion, and the length of time that the therapy should continue. The nurse should also carefully assess a patient's hydration status and oral intake to ensure that IV fluids are stopped appropriately as a patent's condition changes. For example, weight should be assessed daily for patients receiving IV fluids to monitor for fluid overload.

Review how to check the rights of medication administration in the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Electrolyte Imbalance

In addition to rapidly improving hydration status, IV fluids may also be administered to rapidly correct electrolyte imbalances. Infusing fluids with electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium can correct electrolyte imbalances more rapidly and effectively than by oral supplementation. However, nurses must collaborate with the interprofessional team to identify medications that should and should not be given through peripheral veins. Current standards of care consider continuous peripheral infusion therapy of electrolytes to be inappropriate because of potential vascular endothelial damage. Ideally, peripheral IV therapy should be isotonic and consistent with physiological pH; otherwise, central venous access should be used.[16]

Electrolytes administered via the IV route must always be administered cautiously at the correct infusion rate because over supplementation can be deadly. For example, potassium infusions administered too rapidly into a patient's system can cause sudden cardiac arrest.

Blood Administration

Blood and blood components are administered by registered nurses via IV infusion, typically through larger sized IV catheters. Blood and blood components are transfused through a special transfusion administration set that has a filter designed to retain potentially harmful particles. Specific procedures for verifying the correct patient and correct blood product are performed prior to transfusion to prevent transfusion reactions that can be life-threatening. Administration of blood and blood components, including the use of infusion devices and ancillary equipment, and the identification, evaluation, and reporting of adverse events related to transfusion are established in agency policies, procedures, and/or practice guidelines. Read more information about blood administration in the "Administer Blood Products" chapter in Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

Nutrition

Nutritional therapy can be administered through an intravenous route for patients who do not have an adequately functioning gastrointestinal tract and/or are unable to take in food or fluids appropriately. Peripheral nutrition may be ordered through a peripheral IV site for nutritional needs such as albumin replacement.

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) may be ordered for a patient based on their specific electrolyte and/or nutritional needs. TPN is a very concentrated solution that must be administered via a central line. Central lines are placed in a larger vessel rather than a smaller, peripheral vessel. Accessing a central vessel requires additional training and expertise to prevent complications with insertion and is further discussed in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Manage Central Lines” chapter. If a nurse receives an order for TPN therapy for a patient who does not have central line access, the order should be clarified with the prescribing provider.

Medications

The IV route is preferred for the administration of many medications when immediate onset is required. For example, many types of pain medications can be given directly into the bloodstream with a much more rapid onset of action than if they were to be administered orally. Rapid relief of pain can be achieved in minutes rather than hours required for oral medications to reach their peak. Rapid onset can also be achieved with other medications such as those used to treat cardiac emergencies or severe allergic reactions to quickly restore patients to optimal body functioning. Additional information about IV administration of medications is discussed in the Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills "Administer IV Push Medications” chapter.

IV Administration Equipment

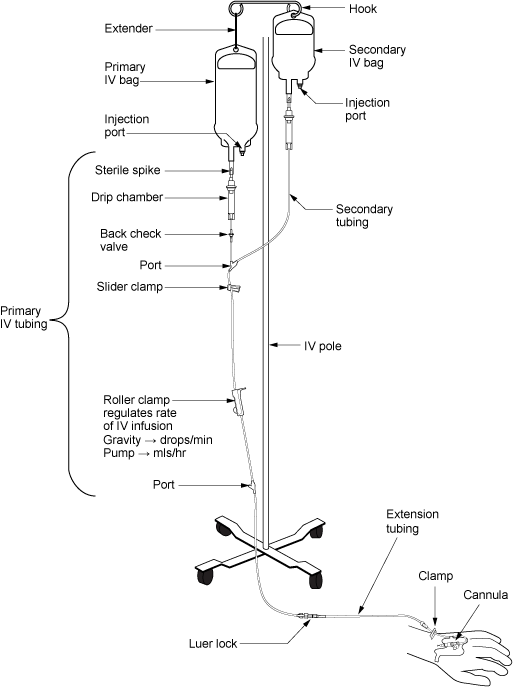

Intravenous (IV) substances are administered through flexible plastic tubing called an IV administration set. The IV administration set connects the bag of solution to the patient’s IV access site. There are two major types of IV administration sets: primary administration sets and secondary administration sets. Administration sets require routine replacement to prevent infection. Follow agency policy regarding tubing changes before initiating a new bag of fluid or medications. See a summary of general guidelines for IV therapy and administration equipment in the box at the end of this section.

Primary Administration Sets

Primary administration sets can be used to infuse continuous or intermittent fluids, electrolytes, or medications. These substances may be administered by infusion pump or by gravity, and each method requires its own type of administration set.

Primary fluids are typically administered using an IV pump. An IV pump is the safest method of administration to ensure specific amounts of fluid are administered. The rate of infusion through an IV pump is typically calculated in mL/hour.

For infusion by gravity, a primary IV administration set can be a macro-drip or a micro-drip solution set. Macro-drip sets are used for routine primary infusions for adults. Micro-drip IV tubing is used in pediatric or neonatal care where small amounts of fluids are administered over a long period of time. A macro-drip infusion set delivers fluid at 10, 15, or 20 drops per milliliter, whereas a micro-drip infusion set delivers 60 drops per milliliter. The drop factor is located on the packaging of the IV tubing and is important to verify when calculating medication administration rates.

Primary IV administration sets consist of the following parts:

- Sterile spike: Used to spike the IV fluid bag and must be kept sterile.

- Roller clamp: Used to regulate the speed or stop an infusion by gravity.

- Drip chamber: Allows air to rise out from a fluid so that it is not passed onto the patient. The drip chamber should be kept ¼ to ½ full of solution. When setting a rate by gravity to "drops per minute," the dripping from this chamber is counted.

- Backcheck valve: Prevents fluid or medication from travelling up into the primary IV bag.

- Access ports: Used to infuse secondary medications and to administer IV push medications. These may also be referred to as “Y ports.”

Secondary Administration Sets

Secondary IV administration sets are used to intermittently administer a secondary medication, such as an antibiotic, while the primary IV is also running. Secondary IV tubing is shorter in length than primary tubing and is connected to a primary line via an access port above the infusion pump. The infusion pump is then set at the prescribed secondary infusion rate while the secondary medication is administered. By hanging the secondary medication bag higher than the primary bag, gravity pulls fluid from the secondary bag until it is empty rather than the primary bag.

Secondary medications may be “piggybacked” into primary infusion lines so the solution from the primary fluid line can be used to prime the secondary tubing. To prime the secondary tubing, after the secondary tubing is connected to the primary tubing, the bag connected to the secondary tubing is held lower than the primary bag, causing fluid from the primary tubing to backflow up the secondary tubing. This eliminates air from the secondary tubing.

See Figure 23.8[17] for an illustration of the setup of primary and secondary administration sets for primary administration of fluids and secondary administration of medication by gravity. See Figure 23.9[18] for an image of an IV infusion pump.

Priming IV Tubing

Primary administration sets, secondary administration sets, and extension tubing must be primed with IV solution to prevent air from entering the patient's circulatory system and causing an air embolism. Priming refers to the process of filling the IV tubing with IV solution prior to attaching it to the patient. Review steps for setting up and priming primary and secondary administration sets using the information in the following box.

Review checklists of steps for "Primary IV Solution Administration" and "Secondary IV Solution Administration" in the "IV Therapy Management" chapter of Open RN Nursing Skills.

Infection Control

Aseptic technique must be maintained throughout all IV therapy procedures, including initiation of IV access, preparing and maintaining IV equipment, administering IV fluids and medications, and discontinuing an IV system. Hand hygiene and strict aseptic technique must be performed when handling all IV equipment. These standards can be reviewed in the “Aseptic Technique” chapter. Additionally, if an IV catheter or IV administration set should become contaminated by contact with a nonsterile surface, it should be replaced with a new one to prevent introducing bacteria or other contaminants into the system.

Types of Venous Access

There are several types of venous access devices used to administer IV therapy that are categorized as peripheral devices or central devices. Venous access device selection is tailored to each patient's needs and to the type, duration, and frequency of infusion.

Peripheral Devices

Peripheral venous access devices are commonly used for short-term IV therapy in the hospital setting. A peripheral IV is an intravenous catheter inserted by percutaneous venipuncture into a peripheral vein and held in place with a sterile transparent dressing. The transparent dressing helps to keep the site sterile, prevents accidental dislodgement, and allows the nurse to visualize the insertion site through the dressing. A securement device may be added to prevent accidental dislodgement.

The patient’s upper extremities (hands and arms) are the preferred sites for insertion. However, a potential limitation of using the hand veins is they are smaller than the cephalic, basilic, or brachial veins in the arm. If the patient requires rapid infusions where a larger gauge IV is warranted, the larger veins in the upper arm should be considered.

Peripheral IVs are used for short-term infusions of fluids, medications, or blood. Peripheral IVs are easy to monitor and can be inserted at the bedside by nurses and other trained professionals. After IV access has been obtained, the hub of an intravenous catheter is attached to a short extension set or a primary IV administration set. Luer lock connectors on the extension tubing and/or administration sets permit syringes to be attached to administer medications or fluid flushes.

Saline lock refers to the use of a short extension set that allows IV access without requiring ongoing IV infusions. When not in use, the lock is flushed with saline according to agency policy and clamped to ensure the site remains sterile and blood does not flow out of the extension tubing. See Figure 23.10[19] for an image of a saline lock.

If the patient requires continuous infusion of IV fluids, the extension tubing from the IV catheter is connected to a primary IV administration set. The IV tubing can be run through an infusion pump to administer fluids or medications at a programmed rate of infusion (typically calculated in mL/hour) or via gravity by setting a drip rate with the roller clamp (typically calculated at drops/minute). Manufacturers list the drop rate on the IV packaging. Because of the risk of error that can occur with infusion by gravity, many agencies require the use of an infusion pump to ensure correct flow rate.

Contraindications to Peripheral IV Access Sites

Before inserting a peripheral IV, the patient should be assessed for contraindications related to insertion sites in the upper extremities. For example, patients who have a history of lumpectomy or mastectomy, an arteriovenous fistula, or current lymphedema often have restrictions that prohibit venipuncture into the affected extremity.[20] Additionally, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), fractures, contractures, or extensive scarring may also prohibit the placement of a peripheral IV. Hospitalized patients may have signage or a bracelet stating "limb alert" to alert heath care professionals to these conditions.

Midline Peripheral Catheters

Midline peripheral catheters have a larger catheter (i.e., 16-18 gauge) that allows for rapid infusions. Insertion is ultrasound-guided and can be inserted by RNs with additional training or other trained professionals. Midline catheters are typically inserted into the basilic, cephalic, or brachial veins of the upper arm with the tip placed near the level of the axilla. They are much longer and inserted deeper than a peripheral IV, but do not extend into a central vessel, so they are not considered a central line. Therefore, they have a lower risk of infection than central venous access. Any medication that can be administered through a peripheral line can be administered via a midline peripheral catheter. They can also be used for longer duration than traditional peripheral venous access, which is ideal for patients needing extended hospital stays or IV access. Based on agency policy, midline catheters may also be used for blood sample collection, thus limiting the number of venipunctures a patient receives. Site care for a midline peripheral catheter is similar to a peripheral IV dressing change.[21],[22]

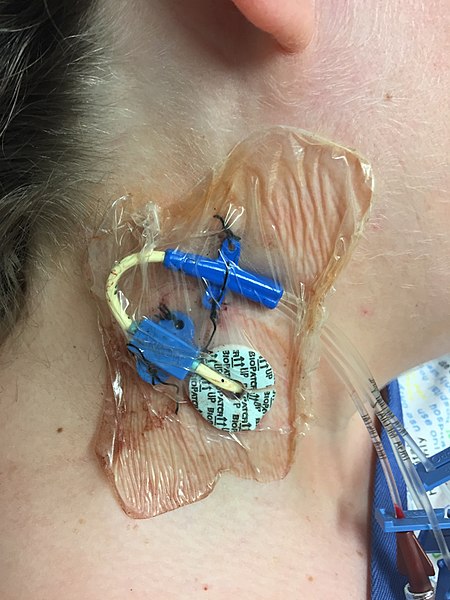

Central Venous Access Devices

A central venous access device (CVAD) is a type of vascular access established by specially trained registered nurses and other health care personnel. It involves the insertion of a tube into a vein in the neck, chest, or groin and threaded into a central vein (most commonly the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral) and advanced until the tip of the catheter resides within the inferior vena cava, superior vena cava, or right atrium.[23] Only specially trained health professionals may insert central venous access devices, but nurses provide routine care of CVADs, including dressing changes. See Figure 23.11[24] for an image of a central line requiring a dressing change.

A central venous access device can be left in for longer periods of time and is useful for administering concentrated medications and fluids, such as TPN or hyperosmotic fluids, that would be otherwise irritating to smaller peripheral veins. However, central venous access devices have an increased risk for the development of bloodstream infections, so strict sterile technique is required during insertion, and aseptic technique is used for maintenance. Central venous access devices are further discussed in the "Manage Central Lines" chapter of Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

Peripheral Inserted Central Catheters

A peripheral inserted central catheter (PICC) is a thin, flexible tube inserted into a vein in the upper arm and guided into the superior vena cava. It is used to give intravenous fluids, blood transfusions, chemotherapy, and other medications requiring a central line. It can also be used for blood sampling. A PICC may stay in place for weeks or months and helps avoid the need for repeated needlesticks. PICC lines are further discussed in the "Manage Central Lines" chapter of Open RN Nursing Advanced Skills.

General Guidelines for IV Therapy

The following are general guidelines for peripheral IV therapy[25]:

- IV fluid therapy is ordered by a provider. The order must include the type of solution or medication, total amount of fluid, rate of infusion, duration, date, and time.

- IV therapy is an invasive procedure. Significant complications can occur if the wrong amount of IV fluids or incorrect medication is given or if aseptic technique is not strictly followed.

- Nurses must understand the indications and duration for IV therapy for each patient. Practice guidelines recommend that patients receiving IV therapy for more than six days should be assessed for an intermediate or long-term device such as a central venous access device (CVAD).

- Hospitalized patients may have an order for a small hourly infusion rate, such as 10-20 mL/hour, historically referred to in practice as a "to keep open" (TKO) or "keep vein open" (KVO) rate.

- IV administration sets require routine replacement to promote patient safety and reduce the risk of infection. Primary and secondary continuous administration sets used to administer solutions other than lipids, blood, or blood products are typically changed every 96 hours, or up to every 7 days, as directed by agency policy and/or the manufacturer’s instructions. Administration sets should also be changed if contamination or compromise in the integrity of the product or system is suspected. Secondary administration sets that are detached from a primary administration set are typically changed every 24 hours or as directed by agency policy. Administration sets should be labelled according to agency policy with the date of initiation or the date of change indicated.[26]

Patterns of interactions between family members that influence family structure, hierarchy, roles, values, and behaviors.