Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

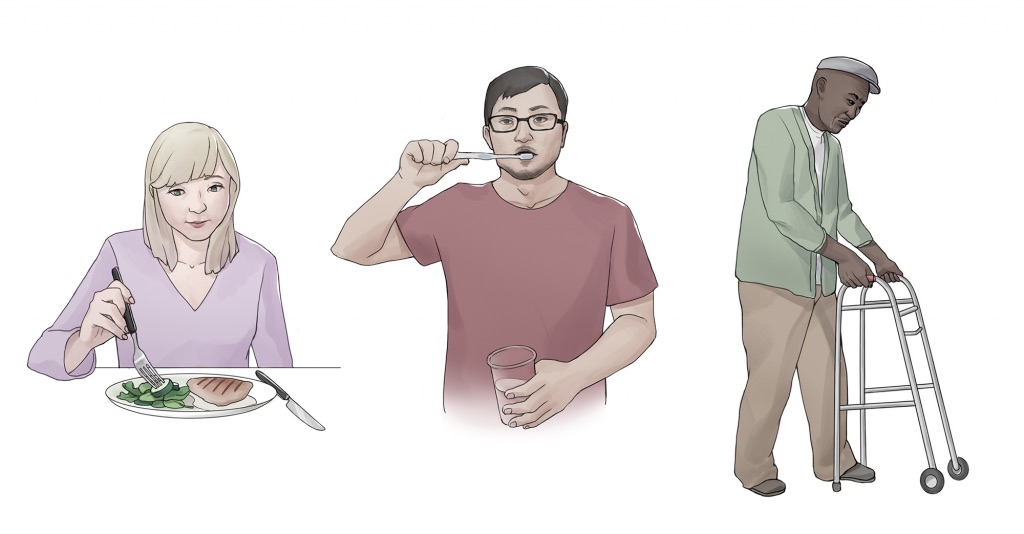

Functional health assessment collects data related to the patient’s functioning and their physical and mental capacity to participate in Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs). Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are daily basic tasks that are fundamental to everyday functioning (e.g., hygiene, elimination, dressing, eating, ambulating/moving). See Figure 2.2[1] for an illustration of ADLs.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) are more complex daily tasks that allow patients to function independently such as managing finances, paying bills, purchasing and preparing meals, managing one’s household, taking medications, and facilitating transportation. See Figure 2.3[2] for an illustration of IADLs. Assessment of IADLs is particularly important to inquire about with young adults who have just moved into their first place, as well as with older patients with multiple medical conditions and/or disabilities.

Information obtained when assessing functional health provides the nurse a holistic view of a patient’s human response to illness and life conditions. It is helpful to use an assessment framework, such as Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns,[3] to organize interview questions according to evidence-based patterns of human responses. Using this framework provides the patient and their family members an opportunity to identify health-related concerns to the nurse that may require further in-depth assessment. It also verifies patient understanding of conditions so that misperceptions can be clarified. This framework includes the following categories:

- Nutritional-Metabolic: Food and fluid consumption relative to metabolic need

- Elimination: Excretion including bowel and bladder

- Activity-Exercise: Activity and exercise

- Sleep-Rest: Sleep and rest

- Cognitive-Perceptual: Cognition and perception

- Role-Relationship: Roles and relationships

- Sexuality-Reproductive: Sexuality and reproduction

- Coping-Stress Tolerance: Coping and effectiveness of managing stress

- Value-Belief: Values, beliefs, and goals that guide choices and decisions

- Self-Perception and Self-Concept: Self-concept and mood state[4]

- Health Perception-Health Management: A patient’s perception of their health and well-being and how it is managed. This is an umbrella category of all the categories above and underlies performing a health history.

The functional health section can be started by saying, “I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.” Focused interview questions for each category are included in Table 2.8. Each category is further described below.

Nutrition

The nutritional category includes, but is not limited to, food and fluid intake, usual diet, financial ability to purchase food, time and knowledge to prepare meals, and appetite. This is also an opportune time to engage in health promotion discussions about healthy eating. Be aware of signs for malnutrition and obesity, especially if rapid and excessive weight loss or weight gain have occurred.

Life Span Considerations

When assessing nutritional status, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depend on the developmental age and health of the patient. Family members may also provide important information.

- Infants: Ask parents about using breast milk or formula, amount, frequency, supplements, problems, and introductions of new foods.

- Pregnant women: Include questions about the presence of nausea and vomiting and intake of folic acid, iron, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and calcium.

- Older adults or patients with disabling illnesses: Inquire about the ability to purchase and cook their food, decreased sense of taste, ability to chew or swallow foods, loss of appetite, and enough fiber and nutrients.[5]

Elimination

Elimination refers to the removal of waste products through the urine and stool. Health care professionals refer to urinating as voiding and stool elimination as having a bowel movement. Familiar terminology may need to be used with patients, such as “pee” and “poop.”

Constipation commonly occurs in hospitalized patients, so it is important to assess the date of their last bowel movement and monitor the frequency, color, and consistency of their stool.

Assess urine concentration, frequency, and odor, especially if concerned about urinary tract infection or incontinence. Findings that require further investigation include dysuria (pain or difficulty upon urination), blood in the stool, melena (black, tarry stool), constipation, diarrhea, or excessive laxative use.[6]

Life Span Considerations

When assessing elimination, the types of questions asked and the level of detail depends on the developmental age and health of the patient.

Toddlers: Ask parents or guardians about toilet training. Toilet training takes several months, occurs in several stages, and varies from child to child. It is influenced by culture and depends on physical and emotional readiness, but most children are toilet trained between 18 months and three years.

Older Adults: Constipation and incontinence are common symptoms associated with aging. Additional focused questions may be required to further assess these issues.[7]

Mobility, Activity, and Exercise

Mobility refers to a patient’s ability to move around (e.g., sit up, sit down, stand up, walk). Activity and exercise refer to informal and/or formal activity (e.g., walking, swimming, yoga, strength training). In addition to assessing the amount of exercise, it is also important to assess activity because some people may not engage in exercise but have an active lifestyle (e.g., walk to school or work in a physically demanding job).

Findings that require further investigation include insufficient aerobic exercise and identified risks for falls.[8]

Life Span Considerations

Mobility and activity depend on developmental age and a patient’s health and illness status. With infants, it is important to assess their ability to meet specific developmental milestones at each well-baby visit. Mobility can become problematic for patients who are ill or are aging and can result in self-care deficits. Thus, it is important to assess how a patient’s mobility is affecting their ability to perform ADLs and IADLs.[9]

Sleep and Rest

The sleep and rest category refers to a patient’s pattern of rest and sleep and any associated routines or sleeping medications used. Although it varies for different people and their life circumstances, obtaining eight hours of sleep every night is a general guideline. Findings that require further investigation include disruptive sleep patterns and reliance on sleeping pills or other sedative medications.[10]

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Disruption in sleep patterns can be especially troublesome for older adults. Assessing sleep patterns and routines will contribute to collaborative interventions for improved rest.[11]

Cognitive and Perceptual

The cognitive and perceptual category focuses on a person’s ability to collect information from the environment and use it in reasoning and other thought processes. This category includes the following:

- Adequacy of vision, hearing, taste, touch, feeling, and smell

- Any assistive devices used

- Pain level and pain management

- Cognitive functional abilities, such as orientation, memory, reasoning, judgment, and decision-making[12]

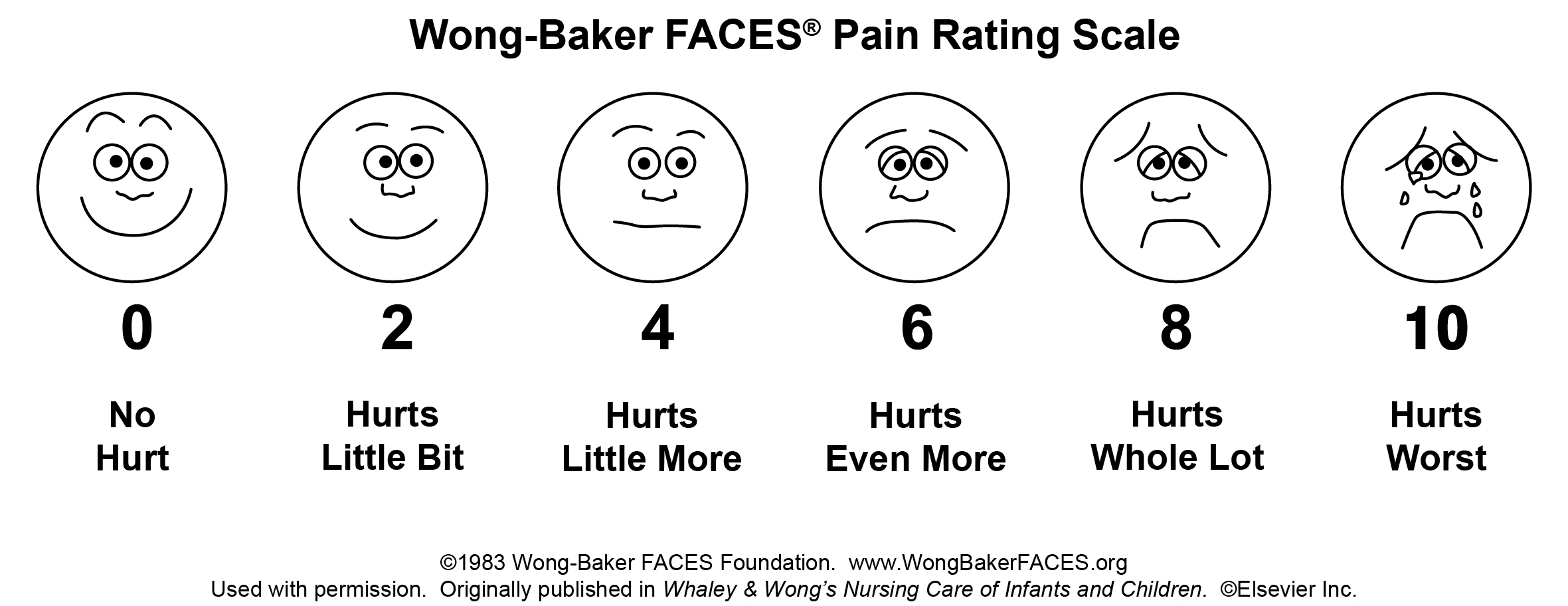

If a patient is experiencing pain, it is important to perform an in-depth assessment using the PQRSTU method described in the “Reason for Seeking Health Care” section of this chapter. It is also helpful to use evidence-based assessment tools when assessing pain, especially for patients who are unable to verbally describe the severity of their pain. See Figure 2.4[13] for an image of the Wong-Baker FACES tool that is commonly used in health care.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults: Older adults are especially at risk for problems in the cognitive and perceptual category. Be alert for cues that suggest deficits are occurring that have not been previously diagnosed.

Roles – Relationships

Quality of life is greatly influenced by the roles and relationships established with family, friends, and the broader community. Roles often define our identity. For example, a patient may describe themselves as a “mother of an 8-year-old.” This category focuses on roles and relationships that may be influenced by health-related factors or may offer support during illness.[14] Findings that require further investigation include indications that a patient does not have any meaningful relationships or has “negative” or abusive relationships in their lives.

Life Span Considerations

Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with any of the following characteristics: isolation from family and friends during crisis, language barriers, loss of a significant person or pet, loss of job, significant home care needs, prolonged caregiving, history of abuse, history of substance abuse, or homelessness.[15]

Sexuality – Reproduction

Sexuality and sexual relations are an aspect of health that can be affected by illness, aging, and medication. This category includes a person’s gender identity and sexual orientation, as well as reproductive issues. It involves a combination of emotional connection, physical companionship (holding hands, hugging, kissing) and sexual activity that impact one’s feeling of health.[16]

The Joint Commission has defined terms to use when caring for diverse patients. Gender identity is a person’s basic sense of being male, female, or other gender.[17] Gender expression are characteristics in appearance, personality, and behavior that are culturally defined as masculine or feminine.[18] Sexual orientation is the preferred term used when referring to an individual’s physical and/or emotional attraction to the same and/or opposite gender.[19] LGBTQ is an acronym standing for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer population. It is an umbrella term that generally refers to a group of people who are diverse in gender identity and sexual orientation. It is important to provide a safe environment to discuss health issues because the LGBTQ population experiences higher rates of smoking, alcohol use, substance abuse, HIV and other STD infections, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and attempts, and eating disorders as a result of stigma and marginalization.[20]

Life Span Considerations

Although sexuality is frequently portrayed in the media, individuals often consider these topics as private subjects. Use sensitivity when discussing these topics with different age groups across cultural beliefs while maintaining professional boundaries.

Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community.

Coping-Stress Tolerance

Individuals experience stress that can lead to dysfunction if not managed in a healthy manner. Throughout life, healthy and unhealthy coping strategies are learned. Coping strategies are behaviors used to manage anxiety. Effective strategies control anxiety and lead to problem-solving but ineffective strategies can lead to abuse of food, tobacco, alcohol, or drugs.[21] Nurses teach and reinforce effective coping strategies.

Substance Use and Abuse

Alcohol, tobacco products, marijuana, and drugs are often used as ineffective coping strategies. It is important to use a nonjudgmental approach when assessing a patient’s use of substances, so they do not feel stigmatized. Substance abuse can affect people of all ages. Make a distinction between use and abuse as you assess frequency of use and patterns of behavior. Substance abuse often causes disruption in everyday function (e.g., loss of employment, deterioration of relationships, or precarious living circumstances) because of dependence on a substance. Action is needed if patients indicate that they have a problem with substance use or show signs of dependence, addiction, or binge drinking.[22]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at increased risk for problems with coping strategies and stress management. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty in medical diagnosis or prognosis, financial problems, marital problems, poor job fit, or few close friends and family members.[23]

Value-Belief

This category includes values and beliefs that guide decisions about health care and can also provide strength and comfort to individuals. It is common for a person’s spirituality and values to be influenced by religious faith. A value is an accepted principle or standard of an individual or group. A belief is something accepted as true with a sense of certainty. Spirituality is a way of living that comes from a set of values and beliefs that are important to a person. The Joint Commission asks health care professionals to respect patients’ cultural and personal values, beliefs, and preferences and accommodate patients’ rights to religious and other spiritual services.[24] When performing an assessment, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to share values and beliefs they believe are important. For example, ask, “I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you during your stay?”

Self-Perception and Self-Concept

The focus of this category is on the subjective thoughts, feelings, and attitudes of a patient about themself. Self-concept refers to all the knowledge a person has about themself that makes up who they are (i.e., their identity). Self-esteem refers to a person’s self-evaluation of these items as being worthy or unworthy. Body image is a mental picture of one’s body related to appearance and function. It is best to assess these items toward the end of the interview because you will have already collected data that contributes to an understanding of the patient’s self-concept. Factors that influence a patient’s self-concept vary from person to person and include elements of life they value, such as talents, education, accomplishments, family, friends, career, financial status, spirituality, and religion.[25] The self-perception and self-concept category also focuses on feelings and mood states such as happiness, anxiety, hope, power, anger, fear, depression, and control.[26]

Life Span Considerations

Some individuals are at risk for problems with self-perception and self-concept. Be sensitive to cues when assessing individuals with characteristics such as uncertainty regarding a medical diagnosis or surgery, significant personal loss, history of abuse or neglect, loss of body part or function, or history of substance abuse.[27]

Violence and Trauma

There are many types of violence that a person may experience, including neglect or physical, emotional, mental, sexual, or financial abuse. You are legally mandated to report suspected cases of child abuse or neglect, as well as suspected cases of elder abuse. At any time, if you or the patient is in immediate danger, follow agency policy and procedure.

Trauma results from violence or other distressing events in a life. Collaborative intervention with the patient is required when violence and trauma are identified. People respond in different ways to trauma. It is important to use a trauma-informed approach when caring for patients who have experienced trauma. For example, a patient may respond to the traumatic situation in a way that seems unfitting (such as with laughter, ambivalence, or denial). This does not mean the patient is lying but can be a symptom of trauma. To reduce the effects of trauma, it is important to implement collaborative interventions to support patients who have experienced trauma.[28]

Loss of Body Part

A person can have negative feelings or perceptions about the characteristics, function, or limits of a body part as a result of a medical condition, surgery, trauma, or mental condition. Pay attention to cues, such as neglect of a body part or negative comments about a body part and use open-ended questions to obtain additional information.

Mental Health

Mental health is frequently underscreened and unaddressed in health care. The mental health of all patients should be assessed, even if they appear well or state they have no mental health concerns so that any changes in condition are quickly noticed and treatment implemented. Mental health includes emotional and psychological symptoms that can affect a patient’s day-to-day ability to function. The World Health Organization (2014) defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes their own potential, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to their community.”[29] Mental illness includes conditions diagnosed by a health care provider, such as depression, anxiety, addiction, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, and others. Mental illness can disrupt everyday functioning and affect a person’s employment, education, and relationships.

It is helpful to begin this component of a mental health assessment with a statement such as, “Mental health is an important part of our lives, so I ask all patients about their mental health and any concerns or questions they may have.”[30] Be attentive of critical findings that require intervention. For example, if a patient talks about feeling hopeless or depressed, it is important to screen for suicidal thinking. Begin with an open-ended question, such as, “Have you ever felt like hurting yourself?” If the patient responds with a “Yes,” then progress with specific questions that assess the immediacy and the intensity of the feelings. For example, you may say, “Tell me more about that feeling. Have you been thinking about hurting yourself today? Have you put together a plan to hurt yourself?” When assessing for suicidal thinking, be aware that a patient most at risk is someone who has a specific plan about self-harm and can specify how and when they will do it. They are particularly at risk if planning self-harm within the next 48 hours. The age of the patient is not a factor in this determination of risk. If you believe the patient is at high risk, do not leave the patient alone. Collaborate with them regarding an immediate plan for emergency care.[31]

Health Perception-Health Management

Health perception-health management is an umbrella term encompassing all of the categories described above, as well as environmental health.

Environmental Health

Environmental health refers to the safety of a patient’s physical environment, also called a social determinant of health. Examples of environmental health include, but are not limited to, exposure to violence in the home or community; air pollution; and availability of grocery stores, health care providers, and public transportation. Findings that require further investigation include a patient living in unsafe environments.[32]

See Table 2.8 for sample focused questions for all categories related to functional health.[33]

Table 2.8 Focused Interview Questions for Functional Health Categories[34]

Begin this section by saying, “I would like to ask you some questions about factors that affect your ability to function in your day-to-day life. Feel free to share any health concerns that come to mind during this discussion.”

| Category | Focused Questions |

|---|---|

| Nutrition | Tell me about your diet.

What foods do you usually eat? What fluids do you usually drink every day? What have you eaten in the last 24 hours? Is this typical of your usual eating pattern? Tell me about your appetite. Have you had any changes in your appetite? Do you have any goals related to your nutrition? Do you have any financial concerns about purchasing food? Are you able to prepare the meals you want to eat? |

| Elimination | When was your last bowel movement?

Do you have any problems with constipation, diarrhea, or incontinence? Do you take laxatives or stool softeners? Do you have any problems urinating, such as frequent urination or burning on urination? Do you ever experience leaking or dribbling of urine? |

| Mobility, Activity, and Exercise | Tell me about your ability to move around.

Do you have any problems sitting up, standing up, or walking? Do you use any mobility aids (e.g., cane, walker, wheelchair)? Tell me about the activity and/or exercise in which you engage. What type? How frequent? For how long? |

| Sleep and Rest | Tell me about your sleep routine. How many hours of sleep do you usually get?

Do you feel rested when you awaken? Do you do anything to wind down before you go to bed (e.g., watch TV, read)? Do you take any sleeping medication? Do you take any naps during the day? |

| Cognitive and Perceptual | Are you having any pain?

Note: If present, use the PQRSTU method to further assess pain. Are you having any issues with seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling things? Have you noticed any changes in memory or problems concentrating? Have you noticed any changes in the ability to make decisions? What is the easiest way for you to learn (e.g., written materials, explanations, or learning-by-doing)? |

| Roles and Relationships | Tell me about the most influential relationships in your life with family and friends.

How do these relationships influence your day-to-day life, health, and illness? Who are the people with whom you talk to when you require support or are struggling in your life? Do you have family or others dependent on you? Have you had any recent losses of someone important to you, a pet, or a job? Do you feel safe in your current relationship? |

| Sexuality-Reproduction | The expression of love and caring in a sexual relationship and creation of family are often important aspects in a person’s life. Do you have any concerns about your sexual health?

Tell me about the ways that you ensure your safety when engaging in intimate and sexual practices. |

| Coping-Stress | Tell me about the stress in your life.

Have you experienced a recent loss in your life that has impacted you? How do you cope with stress? |

| Values-Belief | I am interested in your spiritual and religious beliefs and how they relate to your health. Can you share with me any spiritual beliefs or religious practices that are important to you? |

| Self-Perception and Self-Concept |

Tell me what makes you who you are. How would you describe yourself? Have you noticed any changes in how you view your body or the things you can do? Are these a problem for you? Have you found yourself feeling sad, angry, fearful, or anxious? What helps you to feel better when this happens? Have you ever used any tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, pipes, vaporizers, hookah)? If so, how much? How much alcohol do you drink every week? Have you used cannabis products? If so, how often do you use them? Have you ever used drugs or prescription drugs that were not prescribed for you? If so, what type? Have you ever felt you had a problem with any of these substances because they affected your daily life? If so, tell me more. Do you want to quit any of these substances? Many patients have experienced violence or trauma in their lives. Have you experienced any violence or trauma in your life? How has it affected you? Would you like to talk with someone about it?

|

| Health Perception – Health Management |

Tell me about how you take care of yourself and manage your home. Have you had any falls in the past six months? Do you have enough finances to pay your bills and purchase food, medications, and other needed items? Do you have any current or future concerns about being able to function independently? Tell me about where you live. Do you have any concerns about safety in your home or neighborhood? Tell me about any factors in your environment that may affect your health. Do you have any concerns about how your environment is affecting your health? |

- “ADL-1024x534.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/healthassessment/chapter/functional-health/ ↵

- “iADL-1024x494.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/healthassessment/chapter/functional-health/ ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- Wong-Baker FACES Foundation. (2020). Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2011). Advancing effective communication, cultural competence, and patient- and family-centered care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community: A field guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/lgbtfieldguide_web_linked_verpdf.pdf downloaded from https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/patient-safety-topics/health-equity/#t=_Tab_StandardsFAQs&sort=relevancy ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- The Joint Commission. (2018). The source, 16(1). https://store.jcrinc.com/assets/1/14/ts_16_2018_01.pdf ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes nursing: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning for clinical practice. F. A. Davis Company. ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of The Complete Subjective Health Assessment by Lapum, St-Amant, Hughes, Petrie, Morrell, and Mistry licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

The period of a disease after the initial entry of the pathogen into the host but before symptoms develop.

The disease stage after the incubation period when the pathogen continues to multiply and the host begins to experience general signs and symptoms of illness that result from activation of the immune system, such as fever, pain, soreness, swelling, or inflammation.

Infections that develop rapidly and generally last only 10-14 days.

Blood glucose monitoring is performed on patients with diabetes mellitus and other conditions that cause elevated blood sugar levels. Diabetes mellitus is a common medical condition that affects the body’s ability to produce insulin in the pancreas and use insulin at the cellular level. There are two types of diabetes mellitus, type 1 and type 2. Type 1 diabetes mellitus is an autoimmune disease that damages the beta cells of the pancreas so they do not produce insulin; thus, synthetic insulin must be administered by injection or infusion. It typically begins in childhood or adolescence. Type 2 diabetes mellitus accounts for approximately 95 percent of all cases and is highly correlated with obesity and inactivity. During type 2 diabetes, the cells of the body become resistant to the effects of insulin, and the pancreas increases its production of insulin. However, over time, the pancreas may no longer be able to produce insulin. In many cases, type 2 diabetes can be managed by moderate weight loss, regular physical activity, and a healthy diet. However, if blood glucose levels cannot be controlled with healthy lifestyle choices, oral diabetic medication is prescribed and eventually, the administration of insulin may be required.[1] Prediabetes is a medical condition where blood sugar levels are higher than normal, but not high enough yet to be diagnosed as type 2 diabetes. Approximately one in three American adults have prediabetes. Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that occurs during pregnancy in women who did not have diabetes before they were pregnant.

Diabetic patients require frequent blood glucose monitoring to administer customized medication therapy to prevent long-term complications from occurring. Hospitalized patients who do not have diabetes may also require frequent blood glucose monitoring due to elevations that can occur as a result of the stress of hospitalization, surgical procedures, and side effects of medications. Additionally, patients receiving enteral feedings typically have their blood glucose monitored every six hours. Health care providers prescribe the frequency of blood glucose monitoring; testing is typically performed before meals and at bedtime. For some patients, a standardized sliding-scale insulin protocol may be prescribed with instructions on the medication administration record (MAR) for administration of insulin based on their blood glucose results.[2],[3] See Table 19.2 for an example of a sliding-scale insulin protocol.

Table 19.2 Sample Sliding-Scale Insulin Protocol

Instructions: Check patient’s blood sugar before meals, at bedtime, and as needed for symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Use the following table to administer insulin lispro PRN.

| Blood Sugar Range | Lispro Insulin Instructions |

|---|---|

| Less than 70 | Hold all insulin and initiate hypoglycemia protocol. |

| 70-150 | 0 units |

| 151-174 | 2 units |

| 175-199 | 4 units |

| 200-224 | 6 units |

| 225-249 | 8 units |

| 250-274 | 10 units |

| 275-299 | 12 units |

| Greater than 300 | Administer 14 units and call the provider. |

Hypoglycemia

When caring for patients with diabetes mellitus and monitoring their blood glucose readings, it is important to continually monitor for signs of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia is defined as blood sugar readings less than 70 and signs and symptoms such as the following:

- Shakiness

- Feeling nervous or anxious

- Sweating, chills, and clamminess

- Irritability or impatience

- Confusion

- Fast heartbeat

- Feeling light-headed or dizzy

- Hunger

- Nausea

- Color draining from the skin (pallor)

- Feeling sleepy

- Feeling weak or having no energy

- Blurred/impaired vision

- Tingling or numbness in the lips, tongue, or cheeks

- Headaches

- Coordination problems or clumsiness

- Nightmares or crying out during sleep

- Seizures[4]

A low blood sugar level triggers the release of epinephrine (adrenaline), the “fight-or-flight” hormone. Epinephrine causes the symptoms of hypoglycemia such as a rapid heartbeat, sweating, and anxiety. If a patient’s blood sugar level continues to drop, the brain has impaired functioning. This may lead to seizures and a coma.[5]

If a nurse suspects hypoglycemia is occurring, a blood sugar reading should be obtained, and appropriate actions taken. Most agencies have a hypoglycemia protocol based on the “15-15 Rule.” The 15-15 Rule is to provide 15 grams of carbohydrate and recheck the blood glucose after 15 minutes. If the reading is still below 70 mg/dL, another serving of 15 grams of carbohydrate should be provided and the process continued until the blood sugar is above 70 mg/dL. Fifteen grams of carbohydrate includes options like 4 ounces of juice or regular soda, hard candy, or glucose tablets. If a patient is experiencing severe hypoglycemia and cannot swallow, a glucagon injection or intravenous administration of dextrose may be required.[6]

Hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia is defined as elevated blood glucose and often causes signs and symptoms such as frequent urination and increased thirst. Hyperglycemia occurs when the patient’s body does not produce enough insulin or cannot use the insulin properly at the cellular level. There are many potential causes of hyperglycemia, such as not receiving enough medication to effectively control blood glucose, eating more than planned, exercising less than planned, or increased stress from an illness, surgery, hospitalization, or other life events.

If a patient's blood glucose is greater than 240 mg/dL, their urine is typically checked for ketones. Ketones indicate a condition called ketoacidosis may be occurring. Ketoacidosis occurs in patients whose pancreas is no longer creating insulin, so fats are broken down for energy and waste products called ketones are produced. If the kidneys cannot effectively eliminate ketones in the urine, they build up in the blood and cause ketoacidosis. Ketoacidosis is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate notification of the provider for treatment. Symptoms of ketoacidosis include fruity-smelling breath, nausea, vomiting, very dry mouth, and shortness of breath. Treatment of ketoacidosis often requires the administration of intravenous insulin while the patient is closely monitored in a critical care inpatient unit.[7]

For more information about diabetes mellitus, measuring blood sugar levels, and diabetic medications, visit the "Endocrine" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Glucometer Use

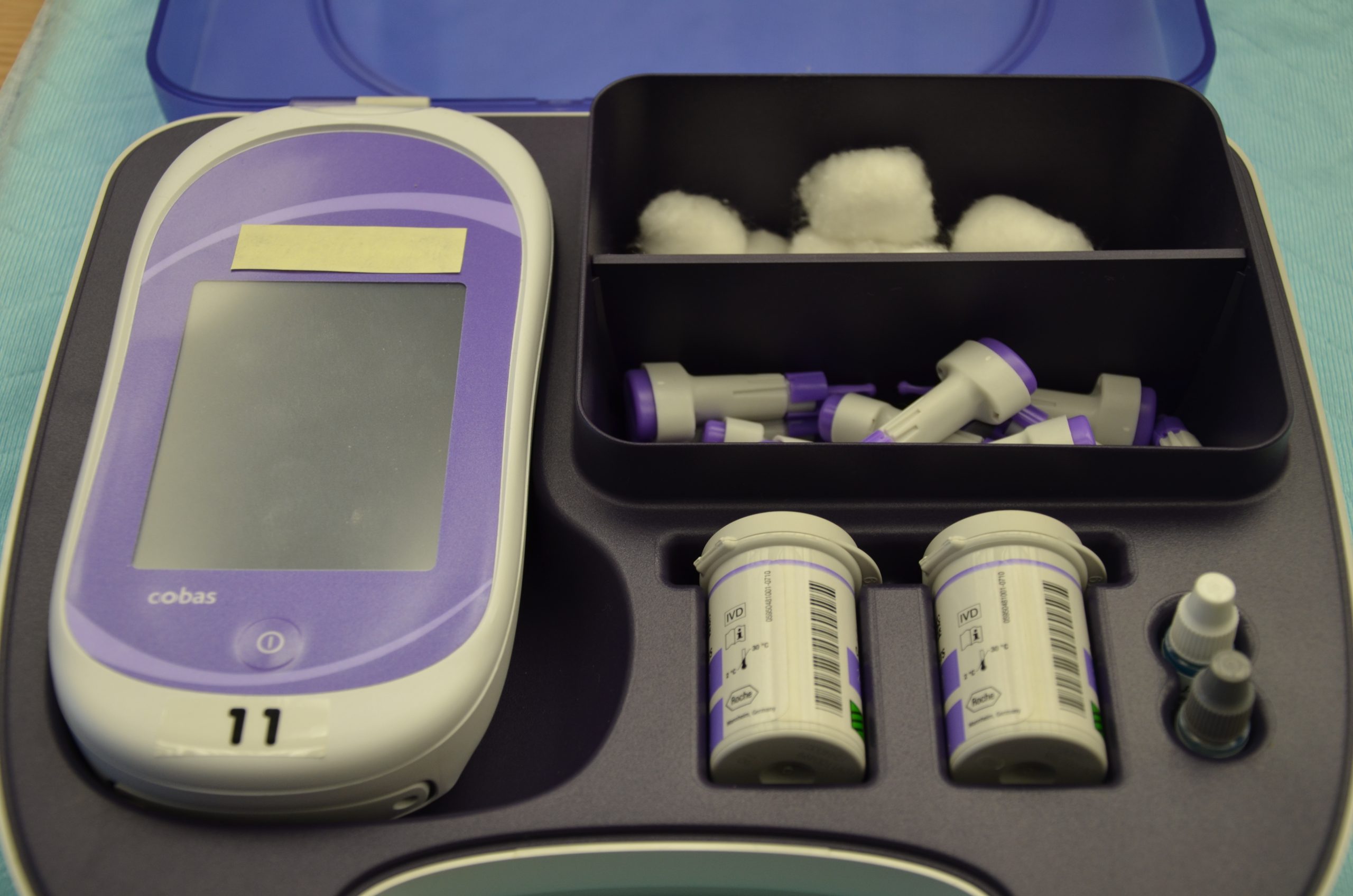

It is typically the responsibility of a nurse to perform bedside blood glucose readings, but in some agencies, this procedure may be delegated to trained nursing assistants or medical assistants. See Figure 19.1[8] for an image of a standard bedside glucometer kit that contains a glucometer, lancets, reagent strips, and calibration drops. Prior to performing a blood glucose test, read the manufacturer’s instructions and agency policy because they may vary across devices and sites. Ensure the glucometer has been calibrated per agency policy.[9]

Before beginning the procedure, determine if there are any conditions present that could affect the reading. For example, is the patient fasting? Has the patient already begun eating? Is the patient demonstrating any symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia? Keep your patient safe by applying your knowledge of diabetes, the medication being administered, and the uniqueness of the patient to make appropriate clinical judgments regarding the procedure and associated medication administration.[10]

See the “Checklist for Blood Glucose Monitoring” for details regarding the procedure. It is often important to keep the patient’s hand warm and in a dependent position to promote vasodilation and obtain a good blood sample. If necessary, warm compresses can be applied for 10 minutes prior to the procedure to promote vasodilation. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to prepare the glucometer for measurement. After applying clean gloves, clean the patient's skin with an alcohol wipe for 30 seconds, allow the site to dry, and then puncture the skin using the lancet. See Figure 19.2[11] for an image of performing a skin puncture using a lancet.

If needed, gently squeeze above the site to obtain a large drop of blood. Do not milk or massage the finger because it may introduce excess tissue fluid and hemolyze the specimen. Wipe away the first drop of blood and use the second drop for the blood sample. Follow agency policy and manufacturer instructions regarding placement of the drop of blood for absorption on the reagent strip. See Figure 19.3[12] for an image of a nurse absorbing the patient’s drop of blood on the reagent strip. Timeliness is essential in gathering an appropriate specimen before clotting occurs or the glucometer times out.

Cleanse the glucometer and document the blood glucose results according to agency policy. Report any concerns about patient symptoms or blood sugar results according to agency policy.

Life Span Considerations

Blood glucose samples should be taken from the heel of newborns and infants up to the age of six months. When obtaining a sample from the heel, the sample is taken from the medial or lateral plantar surface.

View a supplementary YouTube video on Obtaining a Bedside Blood Glucose[13]

Damage that occurs when tissue layers move over the top of each other, causing blood vessels to stretch and break as they pass through the subcutaneous tissue.

The healing of a wound that has had to remain open or has been reopened, often due to severe infection.

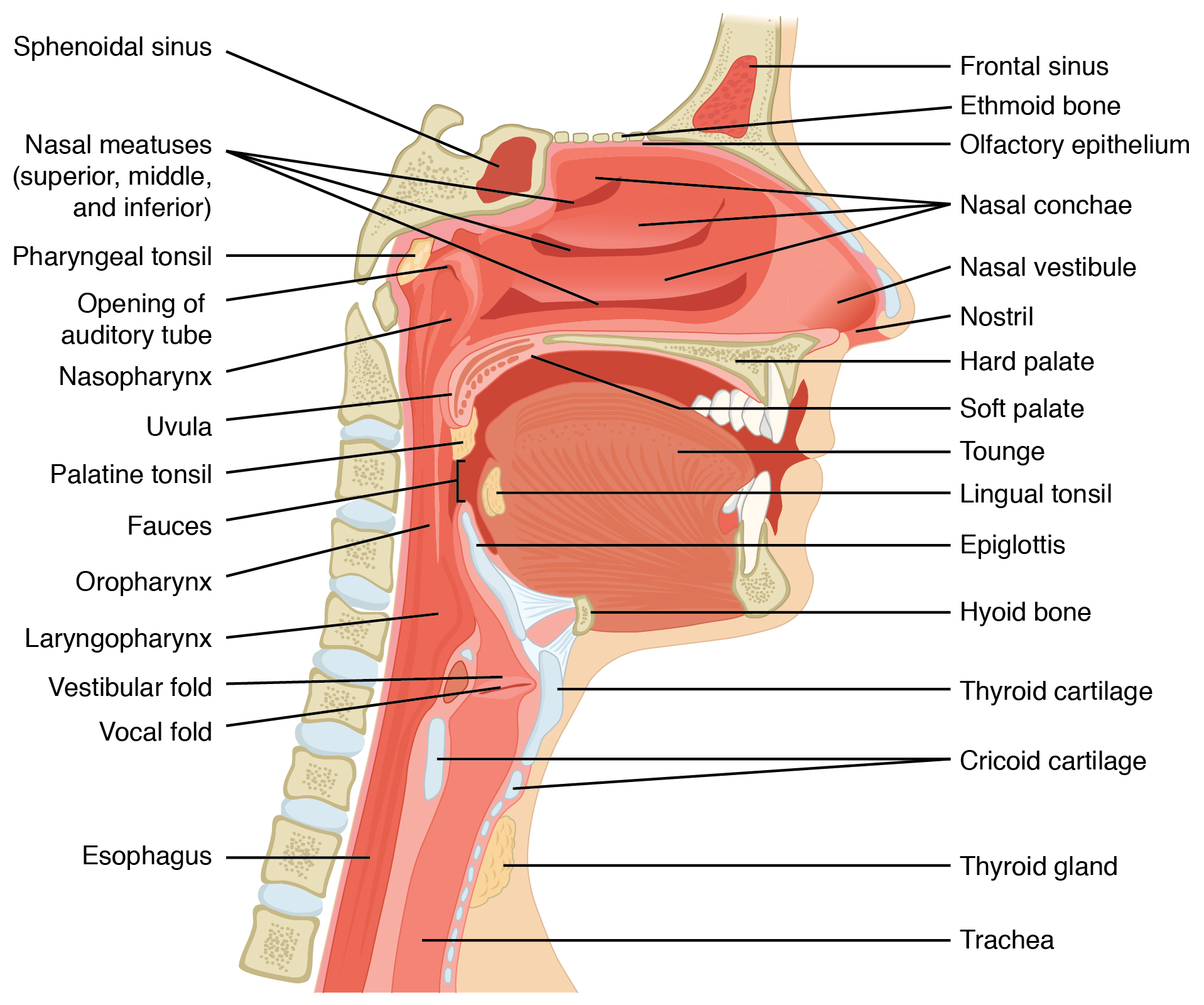

Specimen collections from a patient’s anterior nasal cavity and nasopharynx are used to test for multiple viral illnesses such as influenza and COVID-19. Nasal swabs can be performed by the nurse or the patient with proper education. It is vital to understand the anatomy of these areas to obtain an accurate sample so that patients receive the appropriate care they need. See Figure 19.4[14] for an image of the anatomy of the head and neck.

Review the “Checklist for Obtaining a Nasal Swab” for details about performing a nasal swab procedure.

15-15 Rule: A rule in an agency’s hypoglycemia protocols that includes providing 15 grams of carbohydrate, and then repeating the blood glucose reading in 15 minutes, and then repeating as needed until the patient’s blood glucose reading is above 70.

Hyperglycemia: Elevated blood glucose reading with associated signs and symptoms such as frequent urination and increased thirst.

Hypoglycemia: A blood glucose reading less than 70 associated with symptoms such as irritability, shakiness, hunger, weakness, or confusion. If not rapidly treated, hypoglycemia can cause seizures and a coma.

Ketoacidosis: A life-threatening complication of hyperglycemia that can occur in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus that is associated with symptoms such as fruity-smelling breath, nausea, vomiting, severe thirst, and shortness of breath.

Oropharynx: The part of the throat at the back of the mouth behind the oral cavity. It includes the back third of the tongue, the soft palate, the side and back walls of the throat, and the tonsils.

Standardized sliding-scale insulin protocol: Standardized instructions for administration of adjustable insulin dosages based on a patient’s premeal blood glucose readings.

The oropharynx is the part of the throat at the back of the mouth behind the oral cavity. It includes the back third of the tongue, the soft palate, the side and back walls of the throat, and the tonsils.[17] When obtaining a specimen from this area, it is important to avoid the tongue and teeth. Depending on the test ordered, the nurse may obtain the specimen from the tonsils alone or the posterior pharynx (throat) and the tonsils. Keep in mind that if you are ever unsure about how to accurately obtain a specimen, lab technicians are a great resource.

See the “Checklist for Oropharyngeal Testing” for additional details about performing the procedure.

Life Span Considerations

Infants and Children

Specimen collection on infants and children may require the support of another health care provider or a parent. Educate the patient and the parent about the procedure and the expectations if the parent decides to assist with the specimen collection. During specimen collection, it's important that the patient is immobile to prevent injury to the nasal cavity, nasopharyngeal, or oropharynx.

View a supplementary YouTube video from Medscape on How to Perform a Throat Swab[18].

Sputum specimens collected by expectoration are commonly used for cytology, culture and sensitivity, and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) testing. Cytologic examination identifies abnormal cells such as cancer. Culture and sensitivity testing identifies specific infectious microorganisms and their sensitivity to antibiotics. Optimally, sputum samples used for culture and sensitivity testing should be collected before initiating antibiotic therapy because antibiotics affect the results. AFB testing, along with culture and sensitivity testing, is used to diagnose tuberculosis (TB). When testing for TB, at least three consecutive samples are collected, with at least one being an early morning sample.

Prior to implementing the procedure, it is helpful to ensure the patient is well-hydrated. Hydration helps thin and loosen sputum and increases the likelihood of obtaining an adequate sample. If the patient is prescribed nebulizer treatments, it is helpful to administer this treatment prior to the procedure to help mobilize secretions. It is also important to assess if the patient is experiencing pain related to coughing. For example, pain following chest or abdominal surgery can inhibit the patient from taking deep breaths and expectorating. In this case, pain medication should be provided prior to performing the procedure. Patients can also be encouraged to support surgical wounds with a pillow while coughing to provide additional support and comfort.

It is best to obtain sputum samples in the early morning because secretions accumulate overnight. The patient can rinse their mouth with water prior to the procedure, but avoid mouthwash or toothpaste because these products can affect the microorganisms in the sample. Remove dentures if they are present.

Be aware that droplets and aerosols may be generated when collecting sputum specimens, so use appropriate personal protective equipment when entering the room and during the procedure based on the patient’s condition. Explain the procedure to the patient, the type of specimen required, and the difference between oral secretions and sputum. Position the patient in a seated position in a chair or at the side of the bed or place them in high Fowler’s position.

Instruct the patient to take three slow, deep breaths and then cough deeply. Repeat this process until the patient has produced sputum, with rest periods between each maneuver.

When the patient has mobilized sputum, instruct them to expectorate directly into a sterile specimen container without touching the inside or rim of the container. The specimen should be at least 5 mL (one teaspoon); ask the patient to continue producing and expectorating sputum until this amount is achieved. Assess the sputum specimen to ensure it is sputum and not saliva. Sputum appears thick and opaque, whereas saliva appears thin, clear, and watery.

Cap the specimen container tightly and ensure it is labeled with the patient's name. Place the specimen in a transport bag and send it to the laboratory for analysis. Document the time and date the sputum specimen was collected and the characteristics of the sputum, including amount and color.

If a patient is unable to expectorate a sputum sample, other interventions may be required to mobilize secretions. It is often helpful to collaborate with a respiratory therapist for assistance in this situation. Interventions may include nebulizers, hydration, deep-breathing exercises, chest percussion, and postural drainage. If these interventions are not successful, a sputum sample may be obtained via oropharyngeal or endotracheal suctioning.[19],[20]

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Obtaining a Nasal Swab.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: N95 respirator (or face mask if respirators are not available), gloves, gown, eye protection (goggles or disposable face shields that cover the front and sides of the face), nasal swab, biohazard bag, and physical barriers (e.g., plexiglass), if needed.

- Apply appropriate PPE: gown, N95 respirator (or face mask if a respirator is not available), gloves, and eye protection are needed for staff collecting specimens or working within 6 feet of the person being tested.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Open the sampling kit using clean technique on a clean surface. The kit should contain a biohazard bag, specimen container, and a nasal swab.

- Remove the swab from the container being careful not to touch the soft end with your gloved hand or any other surface, which could contaminate the swab and either obscure the results or infect the patient.

- Insert the swab into the nostril:

- Anterior Nasal Swab: Have the patient tilt their head back at a 70-degree angle. Do not insert the swab more than a half an inch into the nostril.

- Nasopharyngeal Swab: Insert until resistance is encountered or the distance is equivalent to that from the ear to the nostril of the patient, indicating contact with the nasopharynx.

- Leave the swab in place as directed:

- Anterior Nasal Swab: Leave in place for 10 to 15 seconds.

- Nasopharyngeal Swab: Leave the swab in place for several seconds to absorb secretions.

- Gently remove the swab:

- Anterior Nasal Swab: Gently remove the swab after repeating Steps 6 & 7 in the other nostril.

- Nasopharyngeal Swab: Slowly remove the swab while rotating it.

- Place the swab in the sterile tube and snap the end off the swab at the break line. Place the cap on the tube.

- Label the tube with the patient's name, date of birth, medical record number, today’s date, your initials, time, and specimen type.

- Place the specimen into the biohazard bag.

- Remove the nonsterile gloves and place them in the appropriate receptacle.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Follow agency policy regarding transportation of the specimen to the lab. Report results appropriately when they are received.

Stool samples are collected from patients to test for cancer, parasites, or for occult blood (i.e., hidden blood). Follow specific instructions from the laboratory for collecting the sample.

The Guaiac-Based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT) is a commonly used test to find hidden blood in the stool that is not visibly apparent. As a screening test for colon cancer, it is typically obtained by the patient in their home using samples from three different bowel movements. Nurses may assist in gFOBT specimen collection during inpatient care.

Before the test, the patient should avoid red meat for three days and should not take aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, for seven days prior to the test. (Blood from the meat can cause a false positive test, and aspirin and NSAIDS can cause bleeding, leading to a false positive result.) Vitamin C (more than 250 mg a day) from supplements, citrus fruits, or citrus juices should be avoided for 3 to 7 days before testing because it can affect the chemicals in the test and make the result negative, even if blood is present. If possible, avoid testing for occult blood during a female's menstrual cycle. The blood may contaminate the sample and cause a false positive.

To perform a gFOBT in an inpatient setting, perform the following steps.

- Verify the patient has not consumed red meat for three days, has not taken aspirin or NSAIDs for seven days prior to the test, and has not had vitamin C greater than 250 mg daily for the past 3-7 days because these substances can affect the results.

- Explain the procedure to the patient. Ensure collection container is placed within the toilet to collect specimen. Instruct them to flush the toilet before defecating to remove any potential chemicals and to not place toilet paper in the toilet after defecating. Request they notify you when they have had a bowel movement.

- Review the manufacturer's instructions because different test kits may have different instructions. Contact the laboratory with any questions.

- Label the card with the patient’s name and medical information per agency policy. Open the flap of the guaiac test card.

- Apply nonsterile gloves. Use the applicator stick to apply a thin smear of the stool specimen to one of the squares of filter paper on the card. Obtain a second specimen from a different part of the stool and apply it to the second square of filter paper on the card. (Occult blood isn’t typically equally dispersed throughout the stool.)

- Place the labeled test card in a transport bag and send it to the laboratory for analysis.

- If you are working in an agency where nurses apply the guaiac developer solution to the card, allow the specimen to dry for 3 to 5 minutes. Open the reverse side of the card and apply two drops of guaiac developer solution to each square. A blue reaction will occur within 60 seconds if the test is positive. The absence of a blue color after 60 seconds is considered a negative test.

- Document the date and time of the test and any unusual characteristics of the stool sample.[21],[22]

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Blood Glucose Monitoring.”

View an instructor demonstration of Blood Glucose Monitoring[23]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Prepare before completing the procedure:

- Review the patient’s medical history and current medications.

- Note if the patient is receiving anticoagulant therapy. Anticoagulant therapy may result in prolonged bleeding at the puncture site and require pressure to the site.

- Assess the patient for signs and symptoms of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia to correlate data to pursue acute action due to an onset of symptoms.

- Determine if the test requires special timing, for example, before or after meals.

- Blood glucose monitoring is typically performed prior to meals and the administration of antidiabetic medications.

- Review the patient’s medical history and current medications.

- Gather supplies: nonsterile gloves, alcohol swab, lancet, 2" x 2" gauze or cotton ball, reagent strips, and blood glucose meter.

- Determine if the blood glucose meter needs to be calibrated according to agency policy to ensure accuracy of readings.

- Read and understood the manufacturer’s instructions and agency policy for the blood glucose meters.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Have the patient wash their hands with soap and warm water, and position the patient comfortably in a semi-upright position in a bed or upright in a chair. Encourage the patient to keep their hands warm. Washing reduces transmission of microorganisms and increases blood flow to the puncture site.

- Agency policy may require use of an alcohol swab to clean the puncture site.

- Ensure that the puncture site is completely dry prior to skin puncture.

- Remove a reagent strip from the container and reseal the container cap to keep the strips free from damage from environmental factors. Do not touch the test pad portion of the reagent strip.

- Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to prepare the meter for measurement.

- Place the unused reagent strip in the glucometer or on a clean, dry surface (e.g., paper towel) with the test pad facing up, based on manufacturer recommendations.

- Apply nonsterile gloves.

- Keep the area to be punctured in a dependent position. Do not milk or massage the finger site:

- Dependent position will increase blood flow to the area.

- Do not milk or massage the finger because it may introduce excess tissue fluid and hemolyze the specimen.

- Warm water, dangling the hand for 15 seconds, and a warm towel stimulate the blood flow to the fingers.

- Avoid having the patient stand during the procedure to reduce the risk of fainting.

- Select the appropriate puncture site. Cleanse the site with an alcohol swab for 30 seconds and allow it to dry. Perform the skin puncture with the lancet, using a quick, deliberate motion against the patient’s skin:

- The patient may have a preference for the site used. For example, the patient may prefer not to use a specific finger for the skin puncture. However, keep in mind their preferred site may be contraindicated. For example, do not use the hand on the same side as a mastectomy.

- Avoid fingertip pads; use the sides of fingers.

- Avoid fingers that are calloused, have broken skin, or are bruised.

- Gently squeeze above the site to produce a large droplet of blood.

- Do not contaminate the site by touching it.

- The droplet of blood needs to be large enough to cover the test pad on the reagent strip.

- Wipe away the first drop of blood with gauze.

- Transfer the second drop of blood to the reagent strip per manufacturer’s instructions:

- The test pad must absorb the droplet of blood for accurate results. Smearing the blood will alter results.

- The timing and specific instructions for measurement will vary between blood glucose meters. Be sure to read the instructions carefully to ensure accurate readings.

- Apply pressure, or ask the patient to apply pressure, to the puncture site using a 2" x 2" gauze pad or clean tissue to stop the bleeding at the site.

- Read the results on the unit display.

- Turn off the meter and dispose of the test strip, 2" x 2" gauze, and lancet according to agency policy. Use caution with the lancet to prevent an unintentional sharps injury.

- Remove gloves.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, review test results with the patient, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Document the results and related assessment findings. Report critical values according to agency policy, such as values below 70 or greater than 300, and any associated symptoms. Read more about hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in the "Blood Glucose Monitoring" section of this chapter.

Sample Documentation of Expected Findings

Patient alert and oriented x 3, sitting in a wheelchair and awaiting breakfast. Patient denies symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Bedside blood glucose obtained with results of 135 mg/dL. 2 units of regular insulin given subcutaneously left abdomen per sliding scale. Breakfast delivered to the patient.

Sample Documentation of Unexpected Findings

0730: Patient alert and oriented x 3, sitting in a wheelchair and awaiting breakfast. Denies symptoms of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. Bedside blood glucose obtained with results of 185 mg/dL. 6 units of regular insulin given per sliding scale along with 34 units of scheduled NPH insulin given subcutaneously left abdomen as breakfast tray was delivered to patient.

0900: Patient ate 25% of breakfast and complains of headache, fatigue, and dizziness. Patient is shaking and irritable but alert and oriented x 3. Blood glucose was rechecked and results were 65 mg/dL. 4 ounces of orange juice was provided.

0915: Blood glucose rechecked and results were 95 mg/dL. Patient states, “I’m feeling much better and not dizzy anymore.” Shakiness has resolved. Provided a peanut butter sandwich per patient request. Will continue to monitor the patient for signs of hypoglycemia. Call light within reach.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Oropharyngeal Testing.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: testing kit or swab, gloves, tongue depressor, mask, and penlight or flashlight. Other PPE such as a face shield, respiratory, or gown may be required based on the patient condition.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Apply nonsterile gloves. Inform the patient the procedure may be uncomfortable and cause gagging.

- Open the supplies.

- Ask the patient to open their mouth wide and tilt their head back. Using a penlight, inspect oral cavity, pharynx, and tonsils for redness, swelling, pus, or red spots.

- Insert the tongue blade to depress the tongue. If the patient can depress their tongue so that it is out of the way of the swab, the tongue blade may not be needed. Some patients have a strong gag reflex and may resist swabbing. If gagging occurs, stop the procedure, and allow the patient to rest. Attempt again, but ask the patient to focus on the ceiling or close their eyes to facilitate swabbing.

- Insert the swab into the posterior pharynx and tonsillar areas. Rub the swab over both tonsillar pillars and posterior oropharynx and avoid touching the tongue, teeth, and gums.

- Place the swab in the sterile tube and snap the end off swab at the break line. Place the cap on the tube.

- Label the tube with the patient's name, date of birth, medical record number, today’s date, your initials, time, and specimen type.

- Place the specimen into the biohazard bag.

- Remove nonsterile gloves and place them in the appropriate receptacle.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Follow agency policy regarding transportation of the specimen to the lab. Report results appropriately when they are received.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 19, Assignment 1.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 19, Assignment 2.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 19, Assignment 3.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 19, Assignment 4.

![]()

Test your clinical judgment with an NCLEX Next Generation-style question: Chapter 19, Assignment 5.

Learning Objectives

- Assess tissue condition, wounds, drainage, and pressure injuries

- Cleanse and irrigate wounds

- Apply a variety of wound dressings

- Obtain a wound culture specimen

- Use appropriate aseptic or sterile technique

- Explain procedure to patient

- Adapt procedures to reflect variations across the life span

- Recognize and report significant deviations in wounds

- Document actions and observations

Wound healing is a complex physiological process that restores function to skin and tissue that have been injured. The healing process is affected by several external and internal factors that either promote or inhibit healing. When providing wound care to patients, nurses, in collaboration with other members of the health care team, assess and manage external and internal factors to provide an optimal healing environment.[24]

Complex wounds often require care by specialists. Certified wound care nurses assess, treat, and create care plans for patients with complex wounds, ostomies, and incontinence conditions. They act as educators and consultants to staff nurses and other health care professionals. This chapter will discuss wound care basics for entry-level nurses. Request a consultation by a certified wound care nurse when caring for patients with complex or nonhealing wounds.