Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

What is Blood Pressure?

A blood pressure reading is the measurement of the force of blood against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps blood through the body. It is reported in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). This pressure changes in the arteries when the heart is contracting compared to when it is resting and filling with blood. Blood pressure is typically expressed as the reflection of two numbers, systolic pressure and diastolic pressure. The systolic blood pressure is the maximum pressure on the arteries during systole, the phase of the heartbeat when the ventricles contract. This is the top number of a blood pressure reading. Systole causes the ejection of blood out of the ventricles and into the aorta and pulmonary arteries. The diastolic blood pressure is the resting pressure on the arteries during diastole, the phase between each contraction of the heart when the ventricles are filling with blood. This is the bottom number of the blood pressure reading.[1] Therefore, 120/80 indicates the systolic blood pressure is 120 mm Hg and the diastolic blood pressure is 80 mm Hg.

Blood pressure measurements are obtained using a stethoscope and a sphygmomanometer, also called a blood pressure cuff. To obtain a manual blood pressure reading, the blood pressure cuff is placed around a patient’s extremity, and a stethoscope is placed over an artery. For most blood pressure readings, the cuff is usually placed around the upper arm, and the stethoscope is placed over the brachial artery. The cuff is inflated to constrict the artery until the pulse is no longer palpable, and then it is deflated slowly. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that the blood pressure cuff be inflated at least 30 mmHg above the point at which the radial pulse is no longer palpable. The first appearance of sounds, called Korotkoff sounds, are noted as the systolic blood pressure reading. Korotkoff sounds are named after Dr. Korotkoff, who first discovered the audible sounds of blood pressure when the arm is constricted.[2] The blood pressure cuff continues to be deflated until Korotkoff sounds disappear. The last Korotkoff sounds reflect the diastolic blood pressure reading.[3] It is important to deflate the cuff slowly at no more than 2-3 mmHg per second to ensure that the absence of pulse is noted promptly and that the reading is accurate. Blood pressure readings are documented as systolic blood pressure/diastolic pressure, for example, 120/80 mmHg.

Abnormal blood pressure readings can signify an area of concern and a need for intervention. Normal adult blood pressure is less than 120/80 mmHg. Hypertension is the medical term for elevated blood pressure readings of 130/80 mmHg or higher. See Table 3.2 for blood pressure categories according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines.[4] Prior to diagnosing a person with hypertension, the health care provider will calculate an average blood pressure based on two or more blood pressure readings obtained on two or more occasions.

For more information about hypertension and blood pressure medications, visit the “Cardiovascular and Renal System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Hypotension is the medical term for low blood pressure readings less than 90/60 mmHg.[5] Hypotension can be caused by dehydration, bleeding, cardiac conditions, and the side effects of many medications. Hypotension can be of significant concern because of the potential lack of perfusion to critical organs when blood pressures are low. Orthostatic hypotension is a drop in blood pressure that occurs when moving from a lying down (supine) or seated position to a standing (upright) position. When measuring blood pressure, orthostatic hypotension is defined as a decrease in blood pressure by at least 20 mmHg systolic or 10 mmHg diastolic within three minutes of standing. When a person stands, gravity moves blood from the upper body to the lower limbs. As a result, there is a temporary reduction in the amount of blood in the upper body for the heart to pump, which decreases blood pressure. Normally, the body quickly counteracts the force of gravity and maintains stable blood pressure and blood flow. In most people, this transient drop in blood pressure goes unnoticed. However, some patients with orthostatic hypotension can experience light-headedness, dizziness, or fainting. This is a significant safety concern because of the increased risk of falls and injury, particularly in older adults.[6] Orthostatic hypotension is also commonly referred to a postural hypotension. When obtaining orthostatic vital signs, the pulse rate may also be collected. If the pulse increases by 30 beats/minute or more while the patient stands (or sits if unable to stand), this indicates a significant change.

Perform the following actions when obtaining orthostatic vital signs:

- Have the patient stand upright for 1 minute if able.

- Obtain the blood pressure measurement while the patient stands using the same arm and the same equipment as the previous measurement that was taken with patient lying or sitting.

- Obtain the radial pulse again.

- Repeat the blood pressure and radial pulse measurements again at 3 minutes. Waiting several minutes before repeating the measurements allows time for the autonomic nervous system to compensate for blood volume shifts after position change in the patient without orthostatic hypotension.

- If the patient has symptoms that suggest orthostatic hypotension but doesn’t have documented orthostatic hypotension, repeat blood pressure measurement.

Tip: Some patients may not demonstrate significant decreases in blood pressure until they stand for more than 3 minutes.

Table 3.2 Blood Pressure Categories[7]

| Blood Pressure Category | Systolic mm Hg | Diastolic mm Hg |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | Less than 120 | Less than80 |

| Elevated | 120-129 | Less than 80 |

| Stage 1 | 130-139 | 80-89 |

| Stage 2 | 140 or higher | Greater or equal to 90 |

| Hypertensive Crisis | Greater than 180 | Greater than 120 |

View Ahmend Alzawi’s Korotkoff sounds video on YouTube.[8]

Equipment to Measure Blood Pressure

Manual Blood Pressure

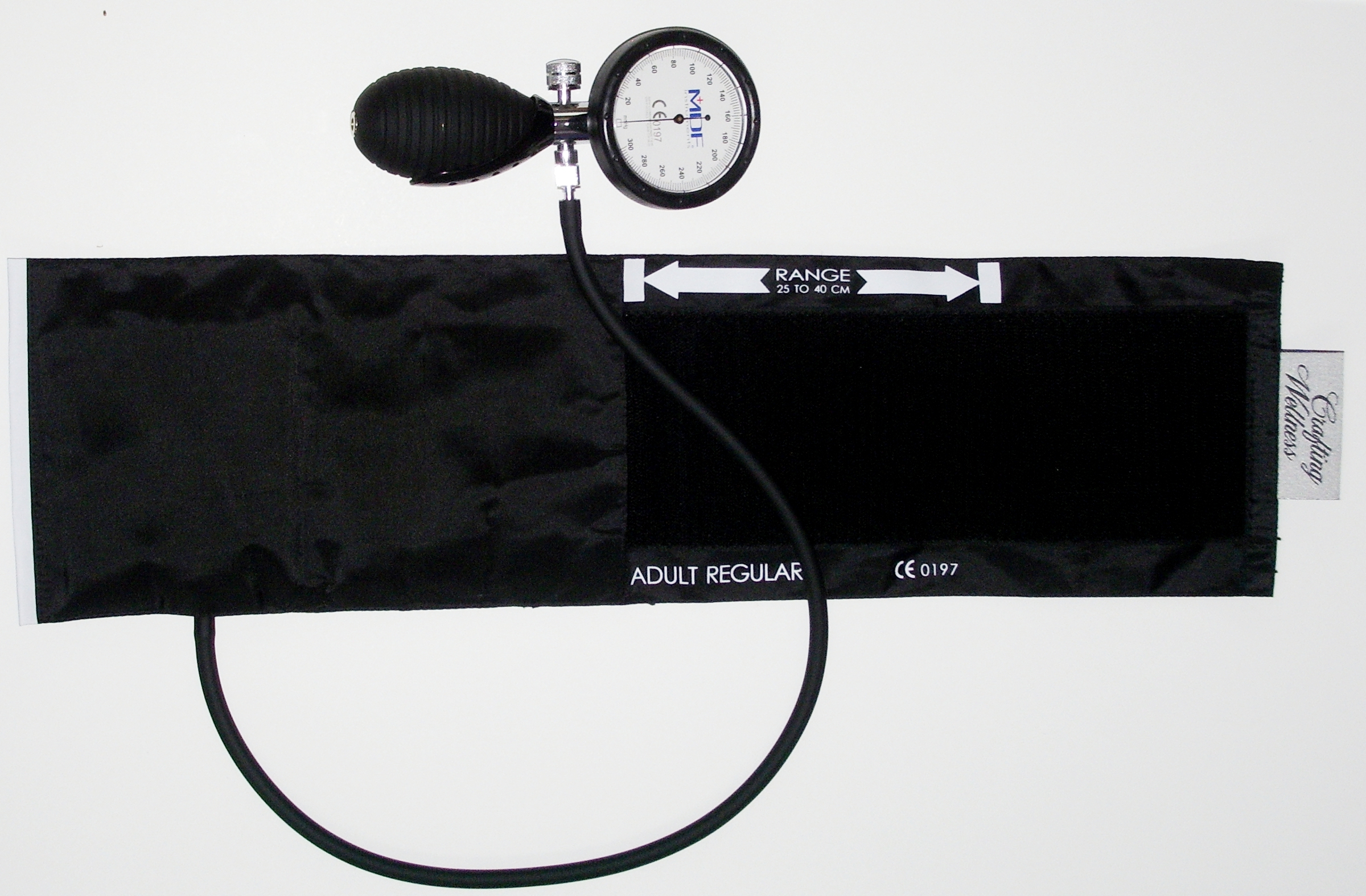

A sphygmomanometer, commonly called a blood pressure cuff, is used to measure blood pressure while Korotkoff sounds are auscultated using a stethoscope. See Figure 3.1[9] for an image of a sphygmomanometer.

There are various sizes of blood pressure cuffs. It is crucial to select the appropriate size for the patient to obtain an accurate reading. An undersized cuff will cause an artificially high blood pressure reading, and an oversized cuff will produce an artificially low reading. See Figure 3.2[10] for an image of various sizes of blood pressure cuffs ranging in size for a large adult to an infant.

The width of the cuff should be 40% of the person’s arm circumference, and the length of the cuff’s bladder should be 80–100% of the person’s arm circumference. Keep in mind that only about half of the blood pressure cuff is the bladder and the other half is cloth with a hook and loop fastener to secure it around the arm.

View Ryerson University’s accurate blood pressure cuff sizing video on YouTube.[11]

Automatic Blood Pressure Equipment

Automatic blood pressure monitors are often used in health care settings to efficiently measure blood pressure for multiple patients or to repeatedly measure a single patient’s blood pressure at a specific frequency such as every 15 minutes. See Figure 3.3[12] for an image of an automatic blood pressure monitor. To use an automatic blood pressure monitor, appropriately position the patient and place the correctly sized blood pressure cuff on their bare arm or other extremity. Press the start button on the monitor. The cuff will automatically inflate and then deflate at a rate of 2 mmHg per second. The monitor digitally displays the blood pressure reading when done. If the blood pressure reading is unexpected, it is important to follow up by obtaining a reading using a manual blood pressure cuff. Additionally, automatic blood pressure monitors should not be used if the patient has a rapid or irregular heart rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation, or has tremors as it may lead to an inaccurate reading.

- This work is a derivative of Vital Sign Measurement Across the Lifespan - 1st Canadian Edition by Ryerson University licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Campbell and Pillarisetty licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American College of Cardiology. Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S.., et al. (2018, May 7). 2017 guidelines for high blood pressure in adults. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2017/11/09/11/41/2017-guideline-for-high-blood-pressure-in-adults ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Low blood pressure. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/low-blood-pressure ↵

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2020, June 23). Orthostatic hypotension. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/orthostatic-hypotension ↵

- American College of Cardiology. Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S.., et al. (2018, May 7). 2017 guidelines for high blood pressure in adults. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2017/11/09/11/41/2017-guideline-for-high-blood-pressure-in-adults ↵

- Alzawi, A. (2015, November 19). Korotkoff+blood+pressure+sights+and+sounds SD [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/UfCr_wUepxo ↵

- “Sphygmomanometer&Cuff.JPG” by ML5 is in the Public Domain. ↵

- “BP-Multiple-Cuff-Sizes.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/vitalsign/chapter/how-is-blood-pressure-measured/ ↵

- Ryerson University. (2018, March 21). Blood pressure - Accurate cuff sizing [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/uNTMwoJTfFE ↵

- “Automatische bloeddrukmeter (0).jpg” by Harmid is in the Public Domain. ↵

Since the days of Florence Nightingale, sleep has been recognized as beneficial to health and of great importance during nursing care due to its restorative function. It is common for sleep disturbances and changes in sleep pattern to occur in connection with hospitalization, especially among surgical clients. Clients in medical and surgical units often report disrupted sleep, not feeling refreshed by sleep, wakeful periods during the night, and increased sleepiness during the day. Illness and the stress of being hospitalized are causative factors, but other reasons for insufficient sleep in hospitals may be due to an uncomfortable bed, being too warm or too cold, environmental noise such as IV pump alarms, disturbance from health care personnel and other clients, and pain. The presence of intravenous catheters, a urinary catheter, and drainage tubes can also impair sleep. Increased daytime sleepiness, a consequence of poor-quality sleep at night, can cause decreased mobility and slower recovery from surgery. Research indicates that postoperative sleep disturbances can last for months. Therefore, it is important to provide effective nursing interventions to promote sleep.[1]

Assessment

Begin a focused assessment on a client’s sleep patterns by asking an open-ended question such as, “Do you feel rested upon awakening?” From there, five key sleep characteristics should be assessed: sleep duration, sleep quality, sleep timing, daytime alertness, and the presence of a sleep disorder. Examples of focused interview questions are included in Table 12.3a. These questions have been selected from sleep health questionnaires from the National Sleep Foundation's Sleep Health Index and the National Healthy Sleep Awareness Project.[2]

Table 12.3a Focused Interview Questions Regarding Sleep[3]

| Questions | Normal Findings |

|---|---|

| How many hours do you sleep on an average night? | 7-8 hours for adults (See Table 12.3b for recommended sleep by age range.) |

| During the past month, how would you rate your sleep quality overall? | Very good or fairly good |

| Do you go to bed and wake up at the same time every day, even on weekends? | Yes, they generally maintain a consistent sleep schedule |

| How likely is it for you to fall asleep during the daytime without intending to? Do you struggle to stay awake while you are doing things? | Unlikely |

| How often do you have trouble going to sleep or staying asleep? | Never, rarely, or sometimes |

| During the past two weeks, how many times did you have loud snoring while sleeping?

Note: It is helpful to ask the client’s sleep partner this question. |

Never |

It is also helpful to determine the effects of caffeine intake and medications on a client’s sleep pattern. If a client provides information causing a concern for impaired sleep patterns or a sleep disorder, it is helpful to encourage them to create a sleep diary to share with a health care provider. Use the following information to view a sample sleep diary.

Download a Sleep Diary from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Additional subjective assessment questions can be used to gather information about a clients typical sleep routine so that it can be mirrored during inpatient care, when feasible.

Nurses also perform objective assessments of a client’s sleep patterns during inpatient care. The number of hours slept, wakefulness during the night, and episodes of loud snoring or apnea should be documented. Note physical (e.g., sleep apnea, pain, and urinary frequency) or psychological (e.g., fear or anxiety) circumstances that interrupt sleep, as well as sleepiness and napping during the day.[4],[5]

Concerns about signs of sleep disorders should be communicated to the health care provider for follow-up.

Life Span Considerations

The amount of sleep needed changes over the course of a person’s lifetime. Although sleep needs vary from person to person, Table 12.3b shows general recommendations for different age groups based on recommendations from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).[6]

Table 12.3b Recommended Amounts of Sleep by Age Group[7]

| Age | Recommended Amount of Sleep |

|---|---|

| Infants aged 4-12 months | 12-16 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 1-2 years | 11-14 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 3-5 years | 10-13 hours a day (including naps) |

| Children aged 6-12 years | 9-12 hours a day |

| Teens aged 13-18 years | 8-10 hours a day |

| Adults aged 18 years or older | 7–8 hours a day |

If an older adult has Alzheimer’s disease, it often changes their sleeping habits. Some people with Alzheimer’s disease sleep too much; others don’t sleep enough. Some people wake up many times during the night; others wander or yell at night. The person with Alzheimer’s disease isn’t the only one who loses sleep. Caregivers may have sleepless nights, leaving them tired for the challenges they face. Educate caregivers about these steps to promote safety for their loved one and help them and the client sleep better at night:

- Make sure the floor is clear of objects.

- Lock up any medications.

- Attach grab bars in the bathroom.

- Place a gate across the stairs.[8]

Diagnostic Tests

A sleep study may be ordered for a client suspected of having a sleep disorder. A sleep study monitors and records data during a client’s full night of sleep. A sleep study may be performed at a sleep center or at home with a portable diagnostic device. If done at a sleep center, the client will sleep in a bed at the sleep center for the duration of the study. Removable sensors are placed on the person’s scalp, face, eyelids, chest, limbs, and a finger to record brain waves, heart rate, breathing effort and rate, oxygen levels, and muscle movements before, during, and after sleep. There is a small risk of irritation from the sensors, but this will resolve after they are removed.[9] See Figure 12.10[10] of an image of a client with sensors in place for a sleep study.

Diagnoses

NANDA-I nursing diagnoses related to sleep include Disturbed Sleep Pattern, Insomnia, Readiness for Enhanced Sleep, and Sleep Deprivation.[11] When creating a nursing care plan for a client, review a nursing care planning source for current NANDA-I approved nursing diagnoses and interventions related to sleep. See Table 12.3c for the definition and selected defining characteristics of Sleep Deprivation.[12]

Table 12.3c Sample NANDA-I Nursing Diagnosis Related to Sleep Deprivation[13]

| NANDA-I Diagnosis | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Deprivation | Prolonged periods of time without sustained natural, periodic suspension of relative consciousness that provides rest. | Agitation

Alteration in concentration Anxiety Apathy Combativeness Decrease in functional ability Decrease in reaction time Drowsiness Fatigue Hallucinations Heightened sensitivity to pain Irritability Restlessness |

A sample nursing diagnostic statement is, “Sleep Deprivation related to an overstimulating environment as evidenced by irritability, difficulty concentrating, and drowsiness.”

Outcome Identification

An overall goal related to sleep is, “The client will awaken refreshed once adequate time is spent sleeping.”[14]

A sample SMART outcome is, “The client will identify preferred actions to ensure adequate sleep by discharge.”[15]

Planning Interventions

Evidence-based nursing interventions to enhance sleep are summarized in the following box.

Sleep Enhancement Interventions[16],[17]

- Adjust the environment (e.g., light, noise, temperature, mattress, and bed) to promote sleep

- Encourage the client to establish a bedtime routine to facilitate wakefulness to sleep

- Facilitate maintenance of the client’s usual bedtime routines during inpatient care

- Encourage elimination of stressful situations before bedtime

- Instruct the client to avoid bedtime foods and beverages that interfere with sleep

- Encourage the client to limit daytime sleep and participate in activity, as appropriate

- Bundle care activities to minimize the number of awakenings by staff to allow for sleep cycles of at least 90 minutes

- Consider sleep apnea as a possible cause and notify the provider for a possible referral for a sleep study when daytime drowsiness occurs despite adequate periods of undisturbed night sleep

- Educate the client regarding sleep-enhancing techniques

Transforming Hospitals Into Restful Environments to Promote Healing

Nurses nationwide have been researching innovative ways to transform hospitals into more restful environments that promote healing. As reported in the American Nurse, strategies include using red lights at night to reduce light exposure, reducing environmental noise, bundling care, offering sleep aids, and providing clienteducation[18]:

- Switching to Red Lights: Nurses can use red lights when providing care at night. Adult and pediatric clients were found to sleep better with reduced white lights.

- Reduce Environmental Noise: Clients were surveyed regarding factors that affected their ability to sleep, and results indicated bed noises, alarms, squeaking equipment, and sounds from other clients. Noise can be reduced by replacing the wheels on the trash cans and squeaky wheels on chairs, repairing malfunctioning motors on beds, switching automatic paper towel machines in the hallways with manual ones, and altering the times floors are buffed. Visitor rules can be implemented, such as no overnight stays in semiprivate rooms and overnight visitors in private rooms were asked to not use their cell phones, turn on the TV, or use bright lights at night.

- Bundling Care: Nurses reinforce bundling care by interdisciplinary team members to reduce sleep interruptions. For example, a “Quiet Time” policy can be set from midnight to 5 a.m. Quiet Time includes dimming lights, closing client room doors, and talking in lower voices.

- Offering Sleep Aids: Nurses can ask clients about what aids they use at home to help them sleep, such as extra pillows or listening to music. On admission, sleep kits can be provided with ear plugs and eye masks and at bedtime, warm washcloths can be offered to clients for comfort.

- Client Education: Clients and families can be provided with printed materials on the benefits of sleep and rest for optimal healing, participating in rehabilitative therapies, and prevention of delirium.

Pharmacological Interventions

See specific information about medications used to facilitate sleep in the previous “Sleep Disorders” section of this chapter.

Implementing Interventions

When implementing interventions to promote sleep, it is important to customize them according to the specific client’s needs and concerns. If medications are administered to promote sleep, fall precautions should be implemented, and the nurse should monitor for potential side effects, such as dizziness, drowsiness, worsening of depression or suicidal thoughts, or unintentionally walking or eating while asleep.

Evaluation

When evaluating the effectiveness of interventions, start by asking the client how rested they feel upon awakening. Determine the effectiveness of interventions based on the established SMART outcomes customized for each client situation.