Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Before learning about cognitive impairment, it is important to understand the physiological processes of normal growth and development. Growth includes physical changes that occur during the development of an individual beginning at the time of conception. Development encompasses these biological changes, as well as social and cognitive changes that occur continuously throughout our lives. Cognition starts at birth and continues throughout the life span. See Figure 6.1[1] for an image of the human life cycle.

There are multiple factors that affect human cognitive development. While there are expected milestones along the way, cognitive development encompasses several different skills that develop at different rates. Cognition takes the form of many paths leading to unique developmental ends. Each human has their own individual experience that influences development of intelligence and reasoning as they interact with one another. With these unique experiences, everyone has a memory of feelings and events that is exclusive to them.[2]

Developmental Stages

As newborns, we learn behavior and communication to help us to interact with the world around us and to fulfill our needs. For example, crying provides communication to cue parents or caregivers about a newborn’s needs. The human brain undergoes tremendous development throughout the first year of life. As infants receive and experience input from the environment, they begin to interact with the individuals around them as they learn and grow.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development

Erikson’s psychosocial development theory emphasizes the social nature of our development rather than its sexual nature. It describes eight sequential stages of individual human development influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors throughout the life span that contribute to an individual’s personality. Erikson’s stages of development are trust versus mistrust, autonomy versus shame, initiative versus guilt, industry versus inferiority, identity versus identity confusion, intimacy versus isolation, generativity versus stagnation, and integrity versus despair.[3],[4]

- Trust vs. Mistrust: The first stage that develops is trust (or mistrust) that basic needs, such as nourishment and affection, will be met. Trust is the basis of our development during infancy (birth to 12 months). Infants are dependent upon their caregivers for their needs. Caregivers who are responsive and sensitive to their infant’s needs help their baby to develop a sense of trust, and the infant will perceive the world as a safe, predictable place. Unresponsive caregivers who do not meet their baby’s needs can engender feelings of anxiety, fear, and mistrust, and the infant will perceive the world as unpredictable.[5]

- Autonomy vs. Shame: Toddlers begin to explore their world and learn that they can control their actions and act on the environment to get results. They begin to show clear preferences for certain elements of the environment, such as food, toys, and clothing. A toddler’s main task is to resolve the issue of autonomy versus shame and doubt by working to establish independence. For example, we might observe a budding sense of autonomy in a two-year-old child who wishes to choose their own clothes and dress themselves. Although the outfits might not be appropriate for the situation, the input in basic decisions has an effect on the toddler’s sense of independence. If denied the opportunity to act on their environment, they may begin to doubt their abilities, which could lead to low self-esteem and feelings of shame.[6]

- Initiative vs. Guilt: After children reach the preschool stage (ages 3–6 years), they are capable of initiating activities and asserting control over their world through social interactions and play. By learning to plan and achieve goals while interacting with others, preschool children can master a feeling of initiative and develop self-confidence and a sense of purpose. Those who are unsuccessful at this stage may develop feelings of guilt.[7]

- Industry vs. Inferiority: During the elementary school stage (ages 7–11), children begin to compare themselves to their peers to see how they measure up. They either develop a sense of pride and accomplishment in their schoolwork, sports, social activities, and family life, or they may feel inferior and inadequate if they feel they don’t measure up to their peers.[8]

- Identity vs. Identity Confusion: In adolescence (ages 12–18), children develop a sense of self. Adolescents struggle with questions such as, “Who am I?” and “What do I want to do with my life?” Along the way, adolescents try on many different selves to see which ones fit. Adolescents who are successful at this stage have a strong sense of identity and are able to remain true to their beliefs and values in the face of problems and other people’s perspectives. Teens who do not make a conscious search for identity, or those who are pressured to conform to their parents’ ideas for the future, may have a weak sense of self and experience role confusion as they are unsure of their identity and confused about the future.[9]

- Intimacy vs. Isolation: People in early adulthood (i.e., 20s through early 40s) are ready to share their lives and become intimate with others after they have developed a sense of self. Adults who do not develop a positive self-concept in adolescence may experience feelings of loneliness and emotional isolation.[10]

- Generativity vs. Stagnation: When people reach their 40s, they enter a time period known as middle adulthood that extends to the mid-60s. The developmental task of middle adulthood is generativity versus stagnation. Generativity involves finding your life’s work and contributing to the development of others through activities such as volunteering, mentoring, and raising children. Adults who do not master this developmental task may experience stagnation with little connection to others and little interest in productivity and self-improvement.[11]

- Integrity vs. Despair: The mid-60s to the end of life is a period of development known as late adulthood. People in late adulthood reflect on their lives and feel either a sense of satisfaction or a sense of failure. People who feel proud of their accomplishments feel a sense of integrity and often look back on their lives with few regrets. However, people who are not successful at this stage may feel as if their life has been wasted. They focus on what “would have,” “should have,” or “could have” been. They face the end of their lives with feelings of bitterness, depression, and despair.[12]

Piaget’s Theory of Development

Jean Piaget, a well-known cognitive development theorist, noted that children explore the world as they attempt to make sense of their experiences. His theory explains that humans move from one stage to another as they seek cognitive equilibrium and mental balance. There are four stages in Piaget’s theory of development that occur in children from all cultures:

- Sensorimotor: The first stage is the sensorimotor period. It extends from birth to approximately two years and is a period of rapid cognitive growth. During this period, infants develop an understanding of the world by coordinating sensory experiences (seeing, hearing) with motor actions (reaching, touching). The main development during the sensorimotor stage is the understanding that objects exist, and events occur in the world independently of one’s own actions.[13] Infants develop an understanding of what they want and what they must do to have their needs met. They begin to understand language used by those around them to make needs met.

- Pre-Operational: Infants progress from the sensorimotor period to a pre-operational period in their toddler years that continues through early school age years. This is the time frame when children learn to think in images and symbols. Play is an important part of cognitive development during this period.

- Concrete Operations: Older school age children (age 7 years to 11 years) enter a concrete operations period. They learn to think in terms of processes and can understand that there is more than one perspective when discussing a concept.[14] This stage is considered a major turning point in the child’s cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought.

- Formal Operations: Adolescents transition to the formal operations stage around age 12 as they become self-conscious and egocentric. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner by manipulating ideas in their head. Moving toward adulthood, this further develops into the ability to critically reason.[15],[16]

Cognitive Impairments in Children

Cognitive impairments in children range from mild impairment in these specific operations to profound intellectual impairments leading to minimal independent functioning. Cognitive impairment is a term used to describe impairment in mental processes that drive how an individual understands and acts in the world, affecting the acquisition of information and knowledge. The following areas are domains of cognitive functioning:

- Attention

- Decision-making

- General knowledge

- Judgment

- Language

- Memory

- Perception

- Planning

- Reasoning

- Visuospatial[17]

Intellectual disability (formerly referred to as mental retardation) is a diagnostic term that describes intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits identified during the developmental period. In the United States, the developmental period refers to the span of time prior to the age 18. Children with intellectual disabilities may demonstrate a delay in developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, speaking, walking) or demonstrate mild cognitive impairments that may not be identified until school age. Intellectual disability is typically nonprogressive and lifelong. It is diagnosed by multidisciplinary clinical assessments and standardized testing and is treated with a multidisciplinary treatment plan that maximizes quality of life.[18] See Figure 6.2[19] for an image of an adolescent with an intellectual disability participating in a Special Olympics event.

Cognitive Impairments in Adults and Older Adults

There are several physical changes that occur in the brain due to aging. The structure of neurons changes, including a decreased number and length of dendrites, loss of dendritic spines, a decrease in the number of axons, an increase in axons with segmental demyelination, and a significant loss of synapses. Loss of synapse is a key marker of aging in the nervous system. These physical changes occur in older adults experiencing cognitive impairments, as well as in those who do not.[20] See Figure 6.3[21] of an older adult experiencing typical physical changes of aging.

It is a common myth that all individuals experience cognitive impairments as they age. Many people are afraid of growing older because they fear becoming forgetful, confused, and incapable of managing their daily life leading to incorrect perceptions and ageism. Ageism refers to stereotyping older individuals because of their age. Losing language skills, becoming unable to make decisions appropriately, and being disoriented to self or surroundings are not normal aging changes.

Dementia, Delirium, and Depression

If cognitive changes in adults occur, a complete assessment is required to determine the underlying cause of the change and if it is caused by an acute or chronic condition. For example, dementia is a chronic condition that affects cognition whereas depression and delirium can cause acute confusion with a similar clinical appearance to dementia.

Dementia

Dementia is a chronic condition of impaired cognition, caused by brain disease or injury, and marked by personality changes, memory deficits, and impaired reasoning. Dementia can be caused by a group of conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, and Lewy body disease. Clinical manifestations of dementia include forgetfulness, impaired social skills, and impaired decision-making and thinking abilities that interfere with daily living. Dementia is gradual, progressive, and irreversible.[22] While dementia is not reversible, appropriate assessment and nursing care improve the safety and quality of life for those affected by dementia.

As dementia progresses and cognition continues to deteriorate, nursing care must be individualized to meet the needs of the client and family. Providing client safety and maintaining quality of life while meeting physical and psychosocial needs are important aspects of nursing care. Unsafe behaviors put individuals with dementia at increased risk for injury. These unsafe or inappropriate behaviors often occur due to the client having a need or emotion without the ability to express it, such as pain, hunger, anxiety, or the need to use the bathroom. The client’s family/caregivers require education and support to recognize that behaviors are often a symptom of dementia and/or a communication of a need and to help them to best meet the needs of their family member.[23]

Delirium

Delirium is an acute state of cognitive impairment that typically occurs suddenly due to a physiological cause, such as infection, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances, drug effects, or other acute brain injury. Sensory overload, excess stress, and sleep deprivation can also cause delirium. Hospitalized older adults are at increased risk for developing delirium, especially if they have been previously diagnosed with dementia. One third of clients aged 70 years or older exhibit delirium during their hospitalization. Delirium is the most common surgical complication for older adults, occurring in 15 to 25% of clients after major elective surgery and up to 50% of clients experiencing hip-fracture repair or cardiac surgery.[24]

The symptoms of delirium usually start suddenly, over a few hours or a few days, and they often come and go. Common symptoms include the following:

- Changes in alertness (usually most alert in the morning and decreased at night)

- Changing levels of consciousness

- Confusion

- Disorganized thinking or talking in a way that does not make sense

- Disrupted sleep patterns or sleepiness

- Emotional changes: anger, agitation, depression, irritability, overexcitement

- Hallucinations and delusions

- Incontinence

- Memory problems, especially with short-term memory

- Trouble concentrating[25]

Delirium and dementia have similar symptoms, so it can be hard to tell them apart. They can also occur together.

Nurses must closely monitor the cognitive function of all clients and promptly report any changes in mental status to the health care provider. The provider will take a medical history, perform a physical and neurological examination, perform mental status testing, and may order diagnostic tests based on the client’s medical history. After the cause of delirium is determined, treatment is targeted to the cause to reverse the effects. See Figure 6.4[26] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing delirium.

General interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older adults are as follows:

- Control the environment. Make sure that the room is quiet and well-lit, have clocks or calendars in view to provide time orientation, and encourage family members to visit.

- Ensure a safe environment with the call light within reach and side rails up as indicated.

- Administer prescribed medications, including those that control aggression or agitation, and pain relievers if there is pain.

- Ensure the client has their glasses, hearing aids, or other assistive devices for communication in place. Lack of assistive sensory devices can worsen delirium.

- Avoid sedatives. Sedatives can worsen delirium.

- Assign the same staff for client care when possible.[28]

Depression

Depression is a brain disorder with a variety of causes, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. It is a commonly untreated condition in older adults and can result in impaired cognition and difficulty in making decisions. It is likely to occur in response to major life events involving health and loved ones. Having other chronic health problems, such as diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease, increases the likelihood for depression in older adults and can cause the loss of their ability to maintain independence.[29] See Figure 6.5[30] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing symptoms of depression.

Symptoms of depression include the following:

- Feeling sad or “empty”

- Loss of interest in favorite activities

- Overeating or not wanting to eat at all

- Not being able to sleep or sleeping too much

- Feeling very tired

- Feeling hopeless, irritable, anxious, or guilty

- Aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems

- Thoughts of death or suicide[31]

Depression is treatable with medication and psychotherapy. However, older adults have an increased risk for suicide, with the suicide rates for individuals over age 85 years the second highest rate overall. Nurses should provide appropriate screening to detect potential signs of depression as an important part of promoting health for older adults.

Comparison of Three Conditions

When an older adult presents with confusion, determining if it is caused by delirium, dementia, depression, or a combination of these conditions can pose many challenges to the health care team. It is helpful to know the client’s baseline mental status from a family member, caregiver, or previous health care records. If a client’s baseline mental status is not known, it is an important safety consideration to assume that confusion is caused by delirium with a thorough assessment for underlying causes.[32] See Table 6.2 for a comparison of symptoms of dementia, delirium, and depression.[33]

Table 6.2 Comparison of Dementia, Delirium, and Depression[34]

| Dementia | Delirium | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Vague, insidious onset; symptoms progress slowly | Sudden onset over hours and days with fluctuations | Onset often rapid with identifiable trigger or life event such as bereavement |

| Symptoms | Symptoms may go unnoticed for years. May attempt to hide cognitive problems or may be unaware of them. Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening (referred to as “sundowning”) | Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory loss and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening | Obvious at early stages and often worse in the morning. Can include subjective complaints of memory loss |

| Consciousness | Normal | Impaired attention/alertness | Normal |

| Mental State | Possibly labile mood. Consistently decreased cognitive performance | Emotional lability with anxiety, fear, depression, aggression. Variable cognitive performance | Distressed/unhappy. Variable cognitive performance |

| Delusions/Hallucinations | Common | Common | Rare |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | Psychomotor disturbance in later stages | Psychomotor disturbance present – hyperactive, purposeless, or apathetic | Slowed psychomotor status in severe depression |

- “shutterstock_149010437.jpg” by Robert Adrian Hillman is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- Vallotton, C. D., & Fischer, K. W. (2008). Cognitive development. Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012370877-9.00038-4 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Orenstein & Lewis and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Psychology 2e by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- McLeod, S. (2020, December 7). Piaget’s theory and stages of development. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html ↵

- Ginsburg, H. P., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget's theory of intellectual development (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc. ↵

- Ginsburg, H. P., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget's theory of intellectual development (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc. ↵

- McLeod, S. (2020, December 7). Piaget’s theory and stages of development. SimplyPsychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html ↵

- Schofield, D. W. (2018, December 26). Cognitive deficits. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/917629-overview ↵

- Schofield, D. W. (2018, December 26). Cognitive deficits. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/917629-overview ↵

- “22605761265_9f8e65a7ad_k.jpg” by Special Olympics 2017 is in the Public Domain ↵

- Murman, D. L. (2015). The impact of age on cognition. Seminars in Hearing, 36(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555115 ↵

- “3546874802_8b4cf9c822_o.jpg” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2021). https://www.alz.org/ ↵

- Downing, L. J., Caprio, T. V., & Lyness, J. M. (2013). Geriatric psychiatry review: Differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D’s - delirium, dementia, and depression. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(6), 365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0365-4 ↵

- Marcantonio, E. R. (2017). Delirium in hospitalized older adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(15), 1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1605501 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Feb 12]. Delirium; [reviewed 2016, May 13; cited 2021, Feb 17]. https://medlineplus.gov/delirium.html ↵

- “old-peoples-home-524234_960_720.jpg” by mikegi is licensed under CC0 ↵

- The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York University, Rory Meyers School of Nursing. (n.d.). Assessment tools for best practices of care for older adults. https://hign.org/consultgeri-resources/try-this-series ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Feb 12]. Delirium; [reviewed 2016, May 13; cited 2021, Feb 17]. https://medlineplus.gov/delirium.html ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- “man-416470_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2021, Feb 6]. Depression; [reviewed 2016, Nov 4; cited 2021, Feb 17]. https://medlineplus.gov/depression.html ↵

- Marcantonio, E. R. (2017). Delirium in hospitalized older adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(15), 1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1605501 ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

A permit issued by the State Board of Nursing (SBON) that allows the applicant to practice practical nursing under the direct supervision of a registered nurse until their RN license is granted.

Three major concepts associated with grieving are loss, grief, and mourning. Loss is the absence of a possession or future possession with the response of grief and the expression of mourning. The feeling of loss can be associated with the loss of health, changes in relationships and roles, and eventually the loss of life. After a client dies, the family members and other survivors experience loss.[1]

Grief is the emotional response to a loss, defined as the individualized and personalized feelings and responses that an individual makes to real, perceived, or anticipated loss. These feelings may include anger, frustration, loneliness, sadness, guilt, regret, and peace. Grief affects survivors physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually. The grief process is not orderly and predictable. Emotional fluctuation is normal and expected. There are times when the person experiencing the loss feels in control and accepting, and there are other times when the loss feels unbearable and they feel out of control.[2] See Figure 17.1[3] for an image of an individual in a cemetery who may be experiencing grief.

Mourning is the outward, social expression of loss. Individuals outwardly express loss based on their cultural norms, customs, and practices, including rituals and traditions. Some cultures may be very emotional and verbal in their expression of loss, such as wailing or crying loudly. Other cultures are stoic and show very little reaction to loss. Culture also dictates how long one mourns and how the mourners “should” act. The expression of loss is also affected by an individual’s personality and previous life experiences.[4]

Types of Grief

There are five different categories of grief: anticipatory grief, acute grief, normal grief, disenfranchised grief, and complicated grief.

Anticipatory Grief

Anticipatory grief is defined as grief before a loss, associated with diagnosis of an acute, chronic, and/or terminal illness experienced by the client, family, or caregivers. Examples of anticipatory grief include actual or fear of potential loss of health, independence, body part, financial stability, choice, or mental function.[5]

Sometimes anticipatory grief starts at the time of a terminal diagnosis and can proceed until the person dies. Clients and their family members can feel anticipatory loss. The client often anticipates the loss of independence, function, or comfort, which can cause significant pain and anxiety if not given the proper support. A client may also have concrete fears such as the loss of the ability to drive, live independently, or maintain their current body image. They may also have grief regarding the loss of anticipated family experiences, such as celebrating the marriage of a child, the birth of a grandchild, an anniversary, or another significant life event. The family often starts grieving for the loss of their loved one before they die as they envision their life without their loved one in it. This type of grief has been shown to help cushion a person’s bereavement reaction.[6]

Acute Grief

Acute grief begins immediately after the death of a loved one and includes the separation response and response to stress. During this period of acute grief, the bereaved person may be confused and/or uncertain about their identity or social role. They may disengage from their usual activities and experience disbelief and shock that their loved one is gone.[7] See Figure 17.2[8] for an image of a sculpture depicting acute grief.

Normal Grief

Normal grief includes the common feelings, behaviors, and reactions to loss. Normal grief reactions to a loss can include the following:

- Physical symptoms such as hollowness in the stomach, tightness in the chest, weakness, heart palpitations, sensitivity to noise, breathlessness, tension, lack of energy, and dry mouth

- Emotional symptoms such as numbness, sadness, fear, anger, shame, loneliness, relief, emancipation, yearning, anxiety, guilt, self-reproach, helplessness, and abandonment

- Cognitive symptoms such as a state of depersonalization, confusion, inability to concentrate, dreams of the deceased, idealization of the deceased, or a sense of presence of the deceased

- Behavioral signs such as impaired work performance, crying, withdrawal, overreactivity, changed relationships, or avoidance of reminders of the deceased[9]

Acute grieving may take months and but can also take years, depending on the loss. No one ever truly gets over the loss, but there is an eventual reconnection with the world of the living as the relationship with the deceased changes.[10]

Disenfranchised Grief

Disenfranchised grief is grief over any loss that is not validated or recognized. Those affected by this type of grief do not feel the freedom to openly acknowledge their grief. Individuals at risk for disenfranchised grief are those who have lost loved ones to stigmatized illnesses or events, such as AIDS. Mothers and/or fathers may grieve over terminated pregnancies or stillborn babies. The loss of a previously severed relationship or divorce can contribute to this type of grief because the individual may not be able to mourn openly due to the circumstances surrounding the relationship.

Complicated Grief

Complicated grief occurs when there is interference in the grieving process leading to a prolonged, more intense grieving. There is often preoccupation with the circumstances of the loss, which may manifest as feelings of guilt regarding the situation around the loss. There is generally a negative focus on the loss, which overrides any positive emotions the person may feel. Complicated grieving can cause significant distress, impaired functioning, and suicidal thinking.[11] Complicated grief is seen in 10-20% of individuals experiencing the death of a romantic partner and with higher estimates for parents who have lost a child. According to the ELNEC, there are four types of complicated grief, including chronic grief, delayed grief, exaggerated grief, and masked grief. Risk factors for developing complicated grief include sudden or traumatic death, suicide, homicide, a dependent relationship with the deceased, chronic illness, death of a child, multiple losses, unresolved grief from prior losses, concurrent stressors, witnessing a difficult dying process such as pain and suffering, lack of support systems, and lack of a faith system. Complicated grief may require professional assistance depending on its severity. Factors that contribute to complicated grief in older adults include lack of a support network, concurrent losses, poor coping skills, and loneliness.[12]

- Chronic Grief: Normal grief reactions that do not subside and continue over very long periods of time.

- Delayed Grief: Normal grief reactions that are suppressed or postponed by the survivor consciously or unconsciously to avoid the pain of the loss.

- Exaggerated Grief: An intense reaction to grief that may include nightmares, delinquent behaviors, phobias, and thoughts of suicide.

- Masked Grief: Grief that occurs when the survivor is not aware of behaviors that interfere with normal functioning as a result of the loss. For example, an individual cancels lunch with friends so they can go to the cemetery daily to visit their loved one’s grave.[13]

Stages of Grief

There are several stages of grief that may occur following a loss. It can be helpful for nurses to have an understanding of these stages to recognize the emotional reactions as symptoms of grief so they can support clients and families as they cope with loss. Famed Swiss psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross identified five main stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying.[14] Clients and families may experience these stages along a continuum, move randomly and repeatedly from stage to stage, or skip stages altogether. There is no one correct way to grieve, and an individual’s specific needs and feelings must remain central to care planning.

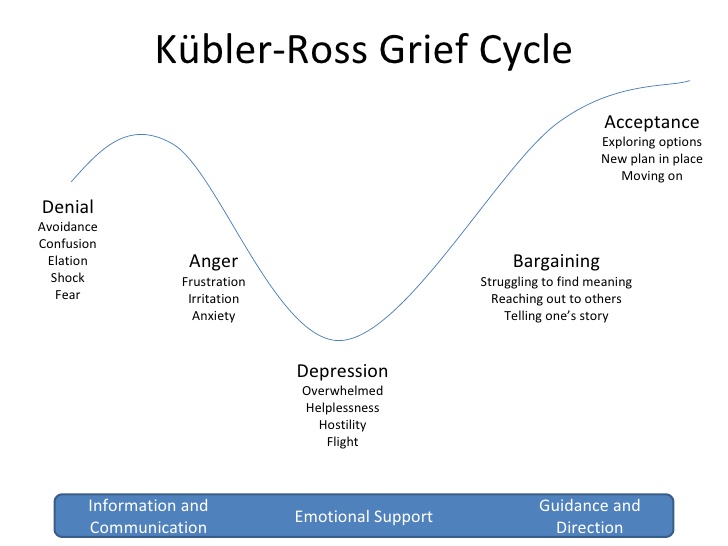

Kuber-Ross identified that clients and families demonstrate various characteristic responses to grief and loss. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, commonly referred to by the mnemonic "DABDA." See Figure 17.3[15] for an illustration of the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle. Keep in mind that these stages of grief not only occur due to loss of life, but also occur due to significant life changes such as divorce, loss of friendships, loss of a job, or diagnosis with a chronic or terminal illness.[16]

View the beginning of this YouTube video clip[17] from the movie Steel Magnolias that shows a mother demonstrating stages of the grieving process.

Denial

Denial occurs when the individual refuses to acknowledge the loss or pretends it isn’t happening. This stage is characterized by an individual stating, “This can’t be happening.” The feeling of denial is self-protective as an individual attempts to numb overwhelming emotions as they process the information. The denial process can help to offset the immediate shock of a loss. Denial is commonly experienced during traumatic or sudden loss or if unexpected life-changing information or events occur. For example, a client who presents to the physician for a severe headache and receives a diagnosis of terminal brain cancer may experience feelings of denial. See Figure 17.4[18] for an image of a person depicting reaction to unexpected news with denial.

Anger

Anger in the grief process often masks pain and sadness. The subject of anger can be quite variable; anger can be directed to the individual who was lost, internalized to self, or projected toward others. Additionally, an individual may lash out at those uninvolved with the situation or have bursts of anger that seemingly have no apparent cause. Health care professionals should be aware that anger may often be directed at them as they provide information or provide care. It is important that health care team members, family members, and others who become the target of anger recognize that the anger and emotion are not a personal attack, but rather a manifestation of the challenging emotions that are a part of the grief process. If possible, the nurse can provide supportive presence and allow the client or family member time to vent their anger and frustration while still maintaining boundaries for respectful discussion. Rather than focusing on what to say or not to say, allowing a safe place for a client or family member to verbalize their frustration, sorrow, and anger can offer great support. See Figure 17.5[19] for an image of a child depicting anger.

Bargaining

Bargaining can occur during the grief process in an attempt to regain control of the loss. When individuals enter this phase, they are looking to find ways to change or negotiate the outcome by making a deal. Some may try to make a deal with God or their higher power to take away their pain or to change their reality by making promises to do better or give more of themselves if only the circumstances were different. For example, a client might say, “I promised God I would stop smoking if He would heal my wife’s lung cancer.”

Depression

Feelings of depression can occur with intense sadness over the loss of a loved one or the situation. Depression can cause loss of interest in activities, people, or relationships that previously brought one satisfaction. Additionally, individuals experiencing depression may experience irritability, sleeplessness, and loss of focus. It is not uncommon for individuals in the depression phase to experience significant fatigue and loss of energy. Simple tasks such as getting out of bed, taking a shower, or preparing a meal can feel so overwhelming that individuals simply withdraw from activity. In the depression phase, it can be difficult for individuals to find meaning, and they may struggle with identifying their own sense of personal worth or contribution. Depression can be associated with ineffective coping behaviors, and nurses should watch for signs of self-medicating through the use of alcohol or drugs to mask or numb depressive feelings. See Figure 17.6[20] for an image of a person depicting feelings of depression.

Acceptance

Acceptance refers to an individual understanding the loss and knowing it will be hard but acknowledging the new reality. The acceptance phase does not mean absence of sadness but is the acknowledgement of one’s capabilities in coping with the grief experience. In the acceptance phase, individuals begin to reengage with others, find comfort in new routines, and even experience happiness with life activities again. See Figure 17.7[21] of an image of a person depicting acceptance.

Grief Tasks

Kubler-Ross's grief stages describe many feelings that individuals commonly experience while grieving loss. Other experts also describe the grieving process in terms of tasks that one must accomplish. These tasks include notification and shock, experiencing the loss, and reintegration.[22]

- Notification and shock: This phase occurs when a person first learns of the loss and experiences feelings of numbness or shock. The person may isolate themselves from others while processing this information. The first task for the person to complete is to acknowledge the reality of the loss by assessing and recognizing the loss.

- Experiencing the loss: The second task involves experiencing the loss emotionally and cognitively. The person must work through the pain by reacting to, expressing, and experiencing the pain of separation and grief.

- Reintegration: The third task involves reorganization and restructuring of family systems and relationships by adjusting to the environment without the deceased. The person must form a new reality without the deceased and adapt to a new role while also retaining memories of the deceased.[23]

As a nurse, you can greatly assist clients and family members as they move through the grieving process by being willing and committed to spending time with them. Listen to their stories, be present, and bear witness to their pain. Remember that you cannot fix everything, but taking time to assess their symptoms of grief helps you identify other resources for support.

Palliative Care and Hospice

Palliative care and hospice care are specialty care areas related to the care of clients and their families experiencing loss and the grieving process.

Palliative care is a broad philosophy of care defined by the World Health Organization as improving the quality of life of clients, as well as their family members, who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual.[24] In the United States, palliative care is further described as, “Patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care occurs throughout the continuum of care and involves the interdisciplinary team collaboratively addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and facilitating patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.”[25] Palliative care focuses on comfort and quality of life but also includes continuing curative treatment such as dialysis, chemotherapy, and surgery.

Hospice care is a type of palliative care that addresses care for clients who are terminally ill when a health care provider has determined they are expected to live six months or less. Like palliative care, hospice provides comprehensive comfort care and support for the family, but in hospice, curative treatments are stopped. It is based on the idea that dying is part of the normal life cycle and supports the client and family through the dying and grief process. It also supports the surviving family members through the bereavement process. Hospice care does not hasten death but focuses on providing comfort while allowing a natural death. Symptoms control, including pain relief, and quality of life are of utmost importance.

Many clients decide to receive hospice care at home with the support of family, nurses, and hospice staff, but hospice services are also available across a variety of settings such as long-term care, assisted living facilities, hospitals, and prisons. In the United States, older adults enrolled in Medicare can choose to receive hospice care and stop receiving curative treatment. It is important to remember that stopping curative treatment does not mean discontinuing all medical treatment. For example, a client with cancer who is no longer responding to chemotherapy can decide to enter hospice care and focus on comfort and quality of life. The chemotherapy treatment will stop, but other medical care, such as blood pressure medications or antibiotics to treat infection, will continue as long as they are helpful in promoting quality of life. Medicare will also pay for all related home durable medical equipment (such as a hospital bed and home oxygen therapy equipment) and all medications related to the terminal diagnosis (including pain medications).[26],[27] See Figure 17.8[28] for an image of a client receiving hospice care.

Unfortunately, instead of viewing hospice as a care option to promote quality of life and reduce suffering, many clients and their families associate hospice care with “giving up,” or as a “death sentence,” and are resistant to this type of care. For this reason, many health care teams advocate the implementation of palliative care until clients and their family members are ready to discuss hospice care.

When a client and their family members make the decision to implement home hospice, their desire is for the client to comfortably spend their final days in their home environment. However, if the client's condition later becomes challenging for family members to manage at home, it can be very difficult to consider transferring the client to a hospice inpatient unit at that time. It is often helpful to encourage clients and family members to tour alternative care agencies when considering hospice and be prepared if this decision is later warranted.

Comfort Care

Comfort care is a term commonly used in the acute care setting that is similar to palliative care and hospice. Comfort care occurs when the clients and medical team’s goals shift from curative intervention to symptom control, pain relief, and quality of life. However, there is no formal admission to hospice or palliative care that can impact insurance coverage. Rather than focusing on aggressive medical intervention, the focus changes to symptom control to provide the client with the greatest degree of comfort possible as they approach their end of life. When comfort care is ordered by the provider, many interventions are eliminated to promote comfort, such as administering medications (with the exception of analgesics or antianxiety medications), monitoring vital sign monitoring, or performing blood draws or other invasive procedures.

Read more about the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care's Palliative Care Guidelines.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

End-of-life care often includes unique complexities for the client, family, and nurse. There may be times when what the physician or nurse believes to be the best treatment conflicts with what the client desires. There may also be challenges related to decision-making that cause disagreements within a family or cause conflict with the treatment plan. Additional challenging factors include availability of resources and insurance company policies and programs.

Despite these complexities, it is important for the nurse to honor and respect the wishes of the client. Despite any conflicts in decision-making among health care providers, family members, and the client, the nurse must always advocate for the client’s wishes. Nurses should also be aware of the practice guidelines for ethical dilemmas stated in the American Nurses Association’s Standards of Professional Nursing Practice and Code of Ethics.[29],[30] These resources assist the nurse in implementing expected behaviors according to their professional role as a nurse.

If complex ethical dilemmas occur, many organizations have dedicated ethics committees that offer support, guidance, and resources for complex ethical decisions. These committees can serve as support systems, share resources, provide legal insight, and make recommendations for action. The nurse should feel supported in raising concerns within their health care organization if they believe an ethical dilemma is occurring.

Review ANA's Code of Ethics.

Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders and Advance Directives

Additional legal considerations when providing care at the end of life are do-not-resuscitate orders (DNR) orders and advance directives. A do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is a medical order that instructs health care professionals not to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if a client's breathing stops or their heart stops beating. The order is only written with the permission of the client (or the client's health care power of attorney, if activated.) Ideally, a DNR order is set up before a critical condition occurs. CPR is emergency treatment provided when a client's blood flow or breathing stops that may involve chest compressions and mouth-to-mouth breathing, electric shocks to stop lethal cardiac rhythms, breathing tubes to open the airway, or cardiac medications. The DNR order only refers to not performing CPR and is recorded in a client's medical record. It is crucial to understand that with a DNR order, clients are still entitled to medical treatment, such as antibiotics, IVs, and medications, and as such, treatment should be rendered when abnormalities are noted or anticipated. Wallet cards, bracelets, or other DNR documents are also available to have at home or in nonhospital settings. The decision to implement a DNR order is typically very difficult for a client and their family members to make.[31] Many people have unrealistic ideas regarding the success rates of CPR and the quality of life a client experiences after being revived, especially for clients with multiple chronic diseases or those receiving palliative care. For example, a recent study found the overall rate of survival leading to hospital discharge for someone who experiences cardiac arrest is about 10.6 percent.[32] Nurses can provide up-to-date health teaching regarding CPR and its effectiveness based on the client's current condition and facilitate discussion about a DNR order.

Advance directives are legal documents that direct care when the client can no longer speak for themselves and include a health care power of attorney and a living will. The health care power of attorney legally identifies a trusted individual to serve as a decision maker for health issues when the client is no longer able to speak for themselves. It is the responsibility of this designated individual to carry out care actions in accordance with the client’s wishes. A health care power of attorney can be a trusted family member, friend, or colleague who is of sound mind and is over the age of 18. They should be someone who the client is comfortable expressing their wishes to and someone who will enact those desired wishes on the client’s behalf.

The health care power of attorney should also have knowledge of the client’s wishes outlined in their living will. A living will is a legal document that describes the client’s wishes if they are no longer able to speak for themselves due to injury, illness, or a persistent vegetative state. The living will addresses issues like ventilator support, feeding tube placement, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and intubation. It is a vital means of ensuring that the health care provider has a record of one’s wishes. However, the living will cannot feasibly cover every possible potential circumstance, so the health care power of attorney is vital when making decisions outside the scope of the living will document.

Read more about advance care planning at the National Institute on Aging and at Honoring Choices Wisconsin.

![]() Nurses must understand the health care practice legalities for the state in which they practice nursing. There can be practice issues in various states that raise additional ethical complexities for the practicing nurse. For example, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and New Mexico all have laws that allow clients to participate in assisted dying practices involving assisted suicide or active euthanasia. In assisted suicide, the client is provided the means to carry out suicide such as a lethal dose of medication. Active euthanasia involves someone other than the client carrying out action to end a person’s life. Most nursing organizations prevent a nurse from participating in assisted dying practices. Nurses must be aware of the Nurse Practice Act in their state and the legalities and ethical challenges of nursing actions surrounding complex issues such as assisted suicide, active euthanasia, and abortion.

Nurses must understand the health care practice legalities for the state in which they practice nursing. There can be practice issues in various states that raise additional ethical complexities for the practicing nurse. For example, Oregon, Washington, Vermont, and New Mexico all have laws that allow clients to participate in assisted dying practices involving assisted suicide or active euthanasia. In assisted suicide, the client is provided the means to carry out suicide such as a lethal dose of medication. Active euthanasia involves someone other than the client carrying out action to end a person’s life. Most nursing organizations prevent a nurse from participating in assisted dying practices. Nurses must be aware of the Nurse Practice Act in their state and the legalities and ethical challenges of nursing actions surrounding complex issues such as assisted suicide, active euthanasia, and abortion.

Caring for the Family of a Dying Client

When caring for a client who is nearing the end of life, the family members require nursing care as well. Fading away is a transition that families make when they realize their seriously ill family member is dying. Although they may have been previously told by a health care provider that their loved one would die from the illness, there is often a sudden realization their family member “is not going to get any better” when their health begins to significantly decline. With this realization comes the transition of fading away.[33]

There are various dimensions that both clients and family members experience during this fading away process:

- Redefining: There is a shift for both clients and families from “what used to be” to “what is now.”

- Burdening: As clients become more dependent, they may feel as if they are a burden to their family--physically, financially, emotionally, socially, and spiritually. Yet, family members typically do not feel the care they are providing is a burden, but rather, “something you do for someone you love.”

- Searching for Meaning: Clients journey inward, seek spiritual reflection, and become more connected to important family members and friends. Family members may search for meaning inwardly through spiritual reflection or explore for meaning with family members and friends.

- Living Day to Day: Clients who eventually find meaning in their illness live each day with a more positive attitude. Family members who try to “make the best of it” make efforts to enjoy the limited time left with their loved one.

- Preparing for Death: Clients often want to leave a legacy. Spouses often want to meet every need of their ill spouse. Clients and family members may begin to make prearrangements for the funeral, as well as get their will and other financial matters in order.

- Contending with Change: Clients and their family members change roles, social patterns, and work patterns. They know the life they used to have will soon be gone.[34]

Nurses can assist clients and family members during the fading away transition by being present and actively listening.

Caregiver Support

Most clients with chronic illness have family caregivers that are an extension of the health care team and work around the clock, all days of the week. They typically provide 70-80% of the care at home. It is important for nurses to assess the caregiver when seeing them with the client in the home, clinic, hospital, or long-term setting and provide encouragement. It is helpful to acknowledge their work is very difficult and to praise them for their efforts.[35] See Figure 17.9[36] for an image of a mother acting as caregiver and supporting her son’s health.

Research shows caregivers often have the following needs[37]:

- Support, assistance, and practical help (e.g., finding others to assist with grocery shopping, going to the pharmacy, and food preparation)

- Honest conversations with the health care team

- Assurance their loved one is being honored

- Inclusion in decision-making

- Desire to be listened to and their concerns heard

- Remembrance as a good and compassionate caregiver

- Assurance that they did all they possibly could for their loved one

Assess the caregiver's needs for further assistance, as well as their social support network. Assess their physical needs, sleep patterns, and ability to perform other responsibilities. Watch for signs of declining health, clinical depression, or signs of increased use of alcohol and drugs. Listen to the caregiver's stories and provide presence, active listening, and touch. Assist them in identifying and using support systems and refer them to resources and support groups in the community as needed.[38]

Cultural Considerations Regarding Death

When assessing clients, family members, and caregivers, it is important to respect their values, beliefs, and traditions related to health, illness, family caregiver roles, and decision-making. Information gathered through this comprehensive assessment is used to develop a nursing care plan that incorporates culturally sensitive resources and strategies to meet the needs of clients and their family members.[39] See Figure 17.10[40] for an image depicting a community grieving.

Nurses can acquire knowledge about how different cultural beliefs influence a client and their family members’ decision-making, approach to illness, pain, spirituality, grief, dying, death, and bereavement. See Table 17.2 for a brief comparison of various spiritual beliefs about death.[41],[42]

To learn more about holistic nursing care that addresses the spiritual needs of clients and their significant others, refer to the “Spirituality” chapter.

Table 17.2 Comparison of Spiritual Beliefs about Death[43]

| Religion | Beliefs Pertaining to Death | Preparation of the Body | Funeral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian

(Catholic and Protestant) |

Belief in Jesus Christ, the Bible, and an afterlife are central, although differences in interpretation exist in the various denominations. Catholics receive a sacrament called “anointing of the sick” when approaching the end of life. | Organ donation and autopsy are permitted. | Individuals are buried in cemeteries. Some denominations accept cremation as an alternative. Funerals or celebration of life services are typically held in a funeral home or church. |

| Jewish | Tradition cherishes life but death itself is not viewed as a tragedy. Views on an afterlife vary with the denomination (Reform, Conservative, or Orthodox). | Autopsy and embalming are forbidden under ordinary circumstances. Open caskets are not permitted. | Funeral is held as soon as possible after death. Dark clothing is worn at the funeral and after burial. It is forbidden to bury the deceased on the Sabbath or during festivals. Three mourning periods may be held after the burial, with Shiva being the first that occurs seven days after burial. |

| Buddhist | Both a religion and way of life with the goal of enlightenment. Life is believed to be a cycle of death and rebirth. | Goal is a peaceful death. Statue of Buddha may be placed at the bedside as the person is dying. Organ donation is not permitted. Incense is lit in the room following death. | Family washes and prepares the body after death. Cremation is preferred, but if buried, deceased are typically dressed in regular daily clothes instead of fancy clothing. Monks may be present at the funeral and lead the chanting. |

| Native American | Beliefs vary among tribes. Sickness is thought to mean that one is out of balance with nature. It is thought that ancestors can guide the deceased. Death is perceived as a journey to another world. Family may or may not be present for death. | Preparation of the body may be done by family. Organ donation is generally not preferred. | Various practices differ with tribes. Among the Navajo, hearing an owl or coyote is a sign of impending death, and the casket is left slightly open so the spirit can escape. Navajo and Apache tribes believe that spirits of the deceased can haunt the living. The Comanche tribe buries the dead in the place of death when possible or in a cave. |

| Hindu | Beliefs include reincarnation where a deceased person returns in the form of another, as well as Karma. | Organ donation and autopsy are acceptable. Death and dying must be peaceful. It is customary for the body to not be left alone until cremated. | Prefer cremation within 24 hours after death. Ashes are often scattered in sacred rivers. |

| Muslim | Believe in an afterlife and that the body must be quickly buried so that the soul may be freed. | Embalming and cremation are not permitted. Autopsy is permitted for legal or medical reasons only. After death, the body should face Mecca or the East. The body should be prepared by a person of the same gender. | Burial takes place as soon as possible. Women and men sit separately at the funeral. Flowers and excessive mourning are discouraged. The body is usually buried in a shroud and is buried with the head pointing toward Mecca. |

Read more about funeral traditions around the globe: Death is not the end: Fascinating funeral traditions from around the globe.

A Good Death

Death is a physical, psychological, social, and spiritual event. Family members who witness the last weeks, days, hours, and minutes of their loved one’s life will remember the death for all their lives. Although death is often perceived negatively in the American culture, research has found several themes that define a “good death” when nurses and the interdisciplinary team are caring for dying clients and their families:[44]

- Client preferences are met, including preferences for the dying process (i.e., where and with whom) and preparation for death (i.e., advanced directives, funeral arrangements).

- The client is pain-free with emotional well-being.

- The family is prepared for death and supportive of client’s preferences.

- Dignity and respect are demonstrated for the client.

- The client has a sense of life completion (i.e., saying goodbye and feeling life was well-lived).

- Spirituality and religious comfort are provided.

- Quality of life was maintained (i.e., maintaining hope, pleasure, gratitude).

- There is a feeling of trust/support/comfort from the nurse and interdisciplinary team.[45]

Nurses are often present during these final days and moments with clients during this difficult and sacred time.[46] Read more about nursing care performed during this time in the “Nursing Care During the Final Hours of Life” section.

Bereavement

The bereavement period includes grief (the inner feelings) and mourning (the outward reactions) after a loved one has died. A bereavement period is the time it takes for the mourner to feel the pain of the loss, mourn, grieve, and adjust to the world without the presence of the deceased. Bereavement can take a physical toll on a survivor. It is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiomyopathy for survivors, and widows and widowers have an increased chance of dying after their spouses die.[47] See Figure 17.11[48] for an image depicting bereavement by family members.

A bereaved person should be encouraged to talk about the death and understand their feelings are normal. They should allow for sufficient time for expression of grief and should postpone significant decisions such as changing jobs or moving. It is also important to encourage them to focus on their spirituality to enhance coping during this difficult time.[49] See Figure 17.12[50] for an image a person depicting one type of spirituality.

Americans often deny the need to express grief or feel the pain that accompanies a loss. However, although painful, both are beneficial to healing. As part of the interdisciplinary health team, nurses are often at the front line of helping clients and family members cope with their feelings of loss and grief. The nursing role during the bereavement period includes the following[51]:

- Assisting with enhanced coping mechanisms

- Assessing and facilitating spirituality

- Facilitating the grieving process by supporting the client and survivors to feel the loss, express the loss, and move through the tasks of grief

- Communicating assessments and interventions with the interdisciplinary team

Children

Children who have experienced the loss of a parent, sibling, grandparent, or friend experience grief based on their developmental stage. It can be normal grief or complicated grief. Children may be limited in their ability to verbalize and describe their feelings and grief. See Figure 17.13[52] for an image of a child depicting grief.

Symptoms of grief in younger children include nervousness, uncontrollable rages, frequent illness, incontinence, rebellious behavior, hyperactivity, nightmares, depression, compulsive behavior, memories fading in and out, excessive anger, overdependence on the remaining parent, denial, and/or disguised anger. Children may not understand that death is permanent until they are in preschool or older. It is important to use the word “death” and not euphemisms like “gone to sleep” or “gone away,” which can be confusing or ambiguous to children. Additionally, using these euphemisms may cause children to fear sleep.[53]

Symptoms of grief in older children include difficulty concentrating, forgetfulness, decreased academic performance, insomnia or sleeping too much, compulsiveness, social withdrawal, antisocial behavior, resentment of authority, overdependence, regression, resistance to discipline, suicidal thoughts or actions, nightmares, symbolic dreams, frequent sickness, accident proneness, overeating or undereating, truancy, experimentation with alcohol or drugs, depression, secretiveness, sexual promiscuity, or running away from home.[54]

Play is the universal language of children, so nurses should use it therapeutically when possible. Encouraging children that their grief is “normal” gives them comfort. Refer children, parents, and families to grief specialists as indicated. Make sure families are aware of local support groups.[55]

Parents and Grandparents

For parents, the death of a child can be devastating with a great need for bereavement support. For grandparents, the grief can be twofold as they experience their own grief, in addition to witnessing the grief of their child (the parent). Studies have shown that grandparents' grief is seldom acknowledged.[56] See Figure 17.14[57] for an image of a sculpture depicting mourning for a child.

For more information on support for parents experiencing infant loss, go to http://nationalshare.org/

Spouses

The death of a husband or wife is well recognized as an emotionally devastating event, being ranked on life event scales as the most stressful of all possible losses. The intensity and persistence of the pain associated with this type of bereavement is thought to be due to the emotional marital bonds linking husbands and wives to each other. Spouses are co-managers of home and family, companions, sexual partners, and fellow members of larger social units.

Therapeutic Communication Tips

When communicating with the bereaved, it is more important to listen and be present rather than say the “right words.” It is also helpful to simply encourage silence. However, certain phrases should be avoided because they can create barriers in therapeutic communication:

- Avoid statements like, “I know/can imagine/understand how you feel.” Even if you have been through a similar situation, you don’t know how the survivor feels. Instead say, “This must be very difficult for you. Would you like to talk about it?”

- Don’t minimize the individual’s grief reaction with a statement like, “You should be over this by now.” Instead, say, “This process takes time, so don’t feel as if you need to rush through it.”

- Avoid statements that minimize the significance of the loss, such as, “At least you had a good life with them,” or "They're in a better place now." Instead, focus on exploring their feelings related to the loss, such as, “Tell me what your relationship was like.”[58]

Completion of the Grieving Process

Grief work is never completely finished because there will always be times when a memory, object, song, or anniversary of the death will cause feelings of loss for the survivor. However, healing occurs and is characterized by the following:

- The pain of the loss is lessened.

- The survivor has adapted to life without the deceased.

- The survivor has physically, psychologically, and socially “let go.”[59]

Letting go is a difficult process. One can let go and still find love and true meaning in the relationship they had with their loved one. Letting go does not mean cutting oneself off from the memories, but adapting to the loss and the continued bonds with the deceased.[60] See Figure 17.15[61] for a depiction of letting go by lighting a candle in memory of the deceased.

Self-Care

It is important for nurses to recognize that providing end-of-life care can have a significant impact on them. A nurse’s grief might be exacerbated when client loss is unexpected or is the result of a traumatic experience. For example, an emergency room nurse who provides care for a child who died as a result of a motor vehicle accident may find it difficult to cope with the loss and resume their normal work duties.

Grief can also be compounded when loss occurs repeatedly in one’s work setting or after providing care for a client for a long period of time. In some health care settings, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses do not have time to resolve grief from a loss before another loss occurs. Compassion fatigue and burnout occur frequently with nurses and other health care professionals who experience cumulative losses that are not addressed therapeutically.

Compassion fatigue is a state of chronic and continuous self-sacrifice and/or prolonged exposure to difficult situations that affect a health care professional’s physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being. This can lead to a person being unable to care for or empathize with someone’s suffering. Burnout can be manifested physically and psychologically with a loss of motivation. It can be triggered by workplace demands, lack of resources to do work professionally and safely, interpersonal relationship stressors, or work policies that can lead to diminished caring and cynicism.[62] See Figure 17.16[63] for an image depicting a nurse at home experiencing burnout due to exposure to multiple competing demands of work, school, and family responsibilities.

Self-care is important to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. It is important for nurses to recognize the need to take time off, seek out individual healthy coping mechanisms, or voice concerns within their workplace. Prayer, meditation, exercise, art, and music are examples of healthy coping mechanisms that nurses can use to progress through their individual grief experience. Additionally, many organizations sponsor employee assistance programs that provide counseling services. These programs can be of great value and benefit in allowing individuals to voice their individual challenges with client loss. In times of traumatic client loss, many organizations hold debriefing sessions to allow individuals who participated in the care to come together to verbalize their feelings. These sessions are often held with the support of chaplains to facilitate individual coping and verbalization of feelings. (Read more about the role of chaplains in the "Spirituality" chapter.)

Throughout your nursing career, there will be times to stop and pay attention to warning signs of compassion fatigue and burnout. Here are some questions to consider:

- Has my behavior changed?

- Do I communicate differently with others?

- What destructive habits tempt me?

- Do I project my inner pain onto others?[64]

By becoming self-aware, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection prevents you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.[65]

In addition to self-care strategies, it is helpful for nurses to obtain additional education in end-of-life care. See the following for more information about obtaining a palliative care certificate for your portfolio.

Read more about online end-of-life curriculum available on the American Association of Colleges of Nursing's End-of-Life-Care Curriculum web page.

Experienced and competent RNs who serve as a role model and a resource to a newly hired nurse.

Grieving a loss is a normal process that has implications for both client and family well-being. NANDA formally recognizes the dimensions of grief with the nursing diagnoses of Grieving and Complicated Grieving. Recall that grief can be experienced due to many types of loss, in addition to death. For example, when clients receive a diagnosis of breast cancer, they may demonstrate signs of various stages of grief, such as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. When undergoing mastectomy and chemotherapy, the client may grieve over the loss of prior body image.

Communities can also experience grief. For example, when a town experiences a significant tragedy, such as a devastating flood or a tornado, there can be widespread community grief as families grieve the loss of life, property, or a previous way of life. In these situations, nurses must be cognizant of the multiple factors that may impact an individual’s health and grieving process. Identifying these factors can help ensure that appropriate resources are mobilized to facilitate coping and progression through the grief process.

Assessment

Grief assessment includes the client, family members, and significant others. It begins when a client is diagnosed with an acute, chronic, or terminal illness and/or when the client is admitted to a hospital, nursing facility, or assisted living facility. It continues throughout the course of a terminal illness for the client, family members, and significant others and then continues through the bereavement period for the survivors. During the bereavement period, the nurse monitors for symptoms of complicated grief.[66]

Grief can be manifested by physical, emotional, and cognitive symptoms. Physical symptoms can occur, such as feeling ill, headaches, tremors, muscle aches, exhaustion, insomnia, loss of appetite, or weight loss or gain. Cognitive symptoms may occur, such as lack of concentration, confusion, and hallucinations. Emotional symptoms, such as anxiety, guilt, anger, fear, sadness, helplessness, or feelings of relief may occur. These symptoms of grief and loss can be manifested in many different ways and can vary from day to day. Manifestations of grief are unique to the individual and may be influenced by one’s age, culture, resources, and previous experiences with loss. Additionally, as clients cope with grief and loss, it is important for the nurse to recognize that support is often needed by their family members.[67]

Any behavior that may endanger the client or family should be reported to the health care provider, such as symptoms of depression, suicidal ideation, or symptoms lasting greater than six months.

Diagnoses

Consult a nursing care planning resource when selecting nursing diagnoses for clients and their family members experiencing grief. See Table 17.3 for definitions and selected defining characteristics of the NANDA-I diagnoses Grieving and Complicated Grieving while also keeping in mind the previous discussion in this chapter regarding stages and tasks of normal grief.

Table 17.3 NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses Related to Grieving[68]

| NANDA-I Diagnosis | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Grieving | A normal, complex process that includes emotional, physical, spiritual, social, and intellectual responses and behaviors by which individuals, families, and communities incorporate an actual, anticipated, or perceived loss into their daily lives. |

|

| Complicated Grieving | A disorder that occurs after the death of a significant other, in which the experience of distress accompanying bereavement fails to follow normative expectations and manifests in functional impairment. |

|

Examples

See the following for examples of PES statements related to Grieving and Complicated Grieving:

- A client diagnosed with metastatic cancer is advised they have less than six months to live. They begin to move through the stages of grief as they assimilate this information. A sample NANDA-I diagnosis in current PES format is: “Grieving related to anticipatory loss as evidenced by detachment, disorganization, and alteration in activity level.” The nurse would plan and implement interventions to enhance coping for this client.

- A clients husband died two years ago, and she continues to be preoccupied with thoughts about her husband. Her grown children live several hours away, and she becomes isolated and unable to complete daily activities, such as cleaning the house and grocery shopping. A sample PES statement is: “Complicated Grieving related to insufficient social support as evidenced by decreased functioning andpreoccupation with thoughts about her deceased husband.” The nurse would plan interventions to facilitate grief work while also arranging for assistance with ADLs in the client’s home.

Outcome Identification

Goal setting and outcome identification for clients and family members experiencing grief are customized to the specific situation and focus on grief resolution. Grief resolution is evidenced by the following indicators:

- Resolves feelings about the loss

- Verbalizes reality and acceptance of loss

- Maintains living environment

- Seeks social support[69]

For the nursing diagnosis of Grieving and Complicated Grieving, a sample goal is, “The client will experience grief resolution.”

A sample SMART outcome is, “The client will discuss the meaning of the loss to their life in the next two weeks.”[70]

Planning and Implementing Interventions

Nurses are in the ideal position to assist clients with identifying and expressing their feelings related to loss. The most important intervention that nurses can provide is active listening and offering a supportive presence. Actively listening to the bereaved helps them express their feelings and relate the emotions and feelings related to the loss. Interventions to facilitate grief resolution focus on coping enhancement, anticipatory grieving interventions, and grief work facilitation.

Coping Enhancement

Interventions to enhance coping can be implemented for clients and families experiencing any type of actual, anticipated, or perceived loss. Sample interventions include the following[71]:

- Assist the client in identifying short- and long-term goals.

- Assist the client in examining available resources to meet the goals.

- Assist the client in breaking down complex steps into small, manageable steps.

- Encourage relationships with others who have common interests and goals.

- Assist the client to solve problems in a constructive manner.

- Appraise the effect of a client’s life situation on roles and relationships.

- Appraise and discuss alternative responses to the situation.

- Use a calm, reassuring approach.

- Provide an atmosphere of acceptance.

- Help the client identify information they are most interested in obtaining.

- Provide factual information regarding medical diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Provide the client with realistic choices about certain aspects of care.