Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[1]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[2]

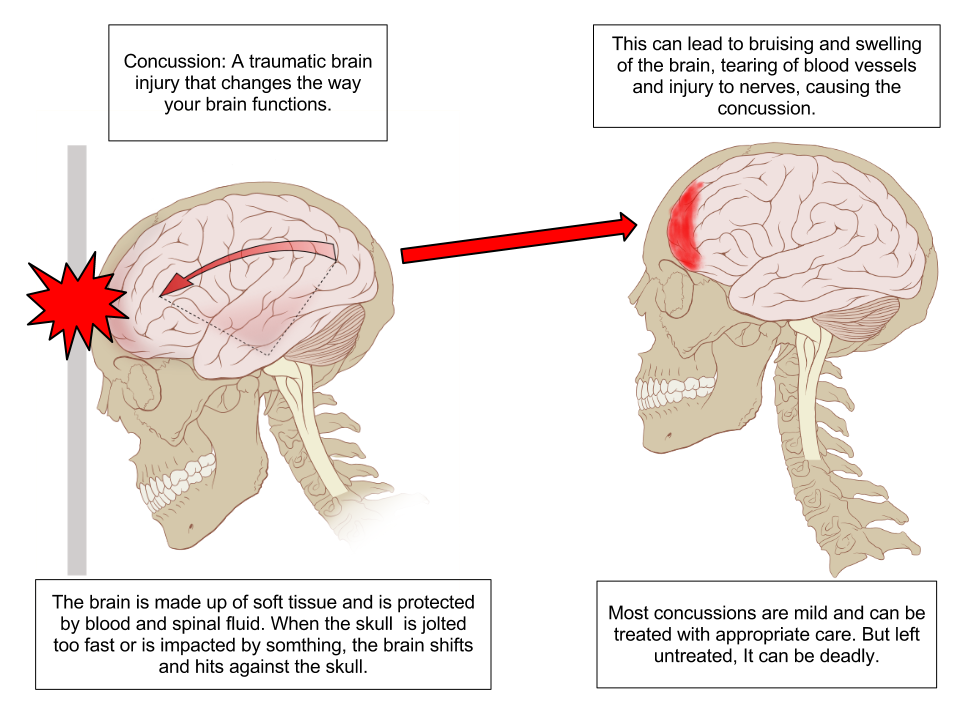

Concussion

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[3] See Figure 7.14[4] for an illustration of a concussion.

Review of Concussions on YouTube[5]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[6]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[7]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Read more information about concussion signs and symptoms on the CDC’s Concussion Signs and Symptoms webpage.

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[8]

See Figure 7.15[9] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[10]

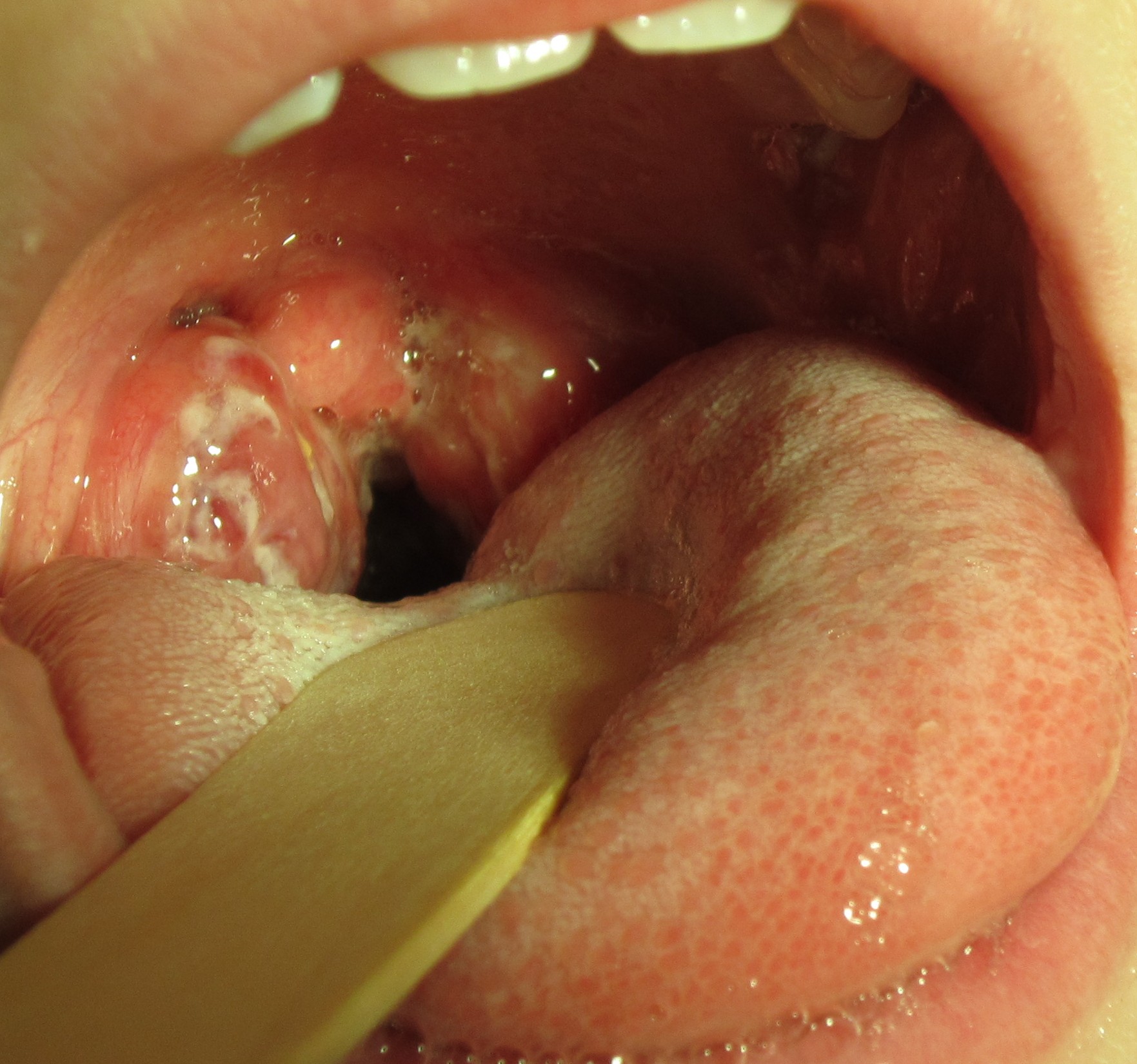

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[11] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[12]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nosebleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[13] See Figure 7.17[14] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[15]

To treat a nosebleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[16] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

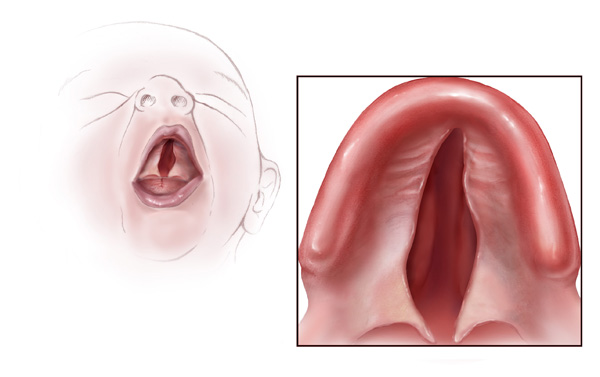

Cleft Lip and Palate

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[17] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[18] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[19]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[20] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[21] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[22]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[23] See Figure 7.21[24] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[25]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- HIV/AIDS

- Taking antibiotics or corticosteroids including inhaled corticosteroids for conditions like asthma

- Taking medications that cause dry mouth or have medical conditions that cause dry mouth

- Smoking

The treatment for mild to moderate cases of candidiasis infections in the mouth or throat is typically an antifungal medicine applied to the inside of the mouth for 7 to 14 days, such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or nystatin.

“Meth Mouth”

The use of methamphetamine (i.e., meth), a strong stimulant drug, has become an alarming public health issue in the United States. A common sign of meth abuse is extreme tooth and gum decay often referred to as “Meth Mouth.” See Figure 7.22[26] for an image of Meth Mouth.

Signs of Meth Mouth include the following:

- Dry Mouth. Methamphetamines dry out the salivary glands, and the acid content in the mouth will start to destroy the enamel on the teeth. Eventually this will lead to cavities.

- Cracked Teeth. Methamphetamine can make the user feel anxious, hyper, or nervous, so they clench or grind their teeth. You may see severe wear patterns on their teeth.

- Tooth Decay. Methamphetamine users crave beverages high in sugar while they are “high.” The bacteria that feed on the sugars in the mouth will secrete acid, which can lead to more tooth destruction. With methamphetamine users, tooth decay will start at the gum line and eventually spread throughout the tooth. The front teeth are usually destroyed first.

- Gum Disease. Methamphetamine users do not seek out regular dental treatment. Lack of oral health care can contribute to periodontal disease. Methamphetamines also cause the blood vessels that supply the oral tissues to shrink in size, reducing blood flow, causing the tissues to break down.

- Lesions. Users who smoke methamphetamine may present with lesions and/or burns on their lips or gingival inside the cheeks or on the hard palate. Users who snort may present with burns in the back of their throats.[27]

Nurses who notice possible signs of “Meth Mouth” should report their concerns to the health care provider, not only for a referral for dental care, but also for treatment of suspected substance abuse.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing that can be caused by many medical conditions. Nurses are often the first health care professionals to notice a patient’s difficulty swallowing as they administer medications or monitor food intake. Early identification of dysphagia, especially after a patient has experienced a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) or other head injury, helps to prevent aspiration pneumonia.[28] Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs and can be life-threatening.

Signs of dysphagia include the following:

- Coughing during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet or gurgly sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort or time required to chew or swallow

- Food or liquid leaking from mouth

- Food getting stuck in the mouth

- Difficulty breathing after meals[29]

The Barnes-Jewish Hospital-Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS) is an example of a simple, evidence-based bedside screening tool that can be used by nursing staff to efficiently identify swallowing impairments in patients who have experienced a stroke. See internet resource below for an image of the dysphagia screening tool. The result of the screening test is recorded as a “fail” if any of the five items tested are abnormal (Glasgow Coma Scale < 13, facial/tongue/palatal asymmetry or weakness, or signs of aspiration on the 3-ounce water test) or “pass” if all five items tested were normal. Patients with a failed screening result are placed on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until further evaluation is completed by a speech therapist. For more information about using the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the “Assessing Mental Status” section in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

View a PDF sample of a Nursing Bedside Swallow Screen.

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Lymphadenopathy is the medical term for swollen lymph nodes. In a child, a node is considered enlarged if it is more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch) wide. See Figure 7.23[30] for an image of an enlarged cervical lymph node.

Common infections such as a cold, pharyngitis, sinusitis, mononucleosis, strep throat, ear infection, or infected tooth often cause swollen lymph nodes. However, swollen lymph nodes can also signify more serious conditions. Notify the health care provider if the patient’s lymph nodes have the following characteristics:

- Do not decrease in size after several weeks or continue to get larger

- Are red and tender

- Feel hard, irregular, or fixed in place

- Are associated with night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Are larger than 1 centimeter in diameter

The health care provider may order blood tests, a chest X-ray, or a biopsy of the lymph node if these signs occur.[31]

Thyroid

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck that controls many of the body’s important functions. The thyroid gland makes hormones that affect breathing, heart rate, digestion, and body temperature. If the thyroid makes too much or not enough thyroid hormone, many body systems are affected. In hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough hormone and many body functions slow down. When the thyroid makes too much hormone, a condition called hyperthyroidism, many body systems speed up.[32]

A goiter is an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland that can occur with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. If you find a goiter when assessing a patient’s neck, notify the health care provider for additional testing and treatment. See Figure 7.24[33] for an image of a goiter.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019, December 31). Headache information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Headache-Information-Page ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2019, December 31). Headache information page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Headache-Information-Page ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- “Concussion Anatomy.png” by Max Andrews is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013, October 24). What is a concussion? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/Sno_0Jd8GuA ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, February 12). Concussion signs and symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/basics/concussion_symptoms.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “EpiduralHeatoma.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Sinusitis; [updated 2020, Jun 10; reviewed 2016, Oct 26]; [cited 2020, Sep 4]; https://medlineplus.gov/sinusitis.html ↵

- “Strep throat2010.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, May 1). Disparities in oral health. https://www.cdc.gov/OralHealth/oral_health_disparities/ ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- “Epstaxis1.jpg” by Welleschik is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Fatakia, A., Winters, R., & Amedee, R. G. (2010). Epistaxis: A common problem. The Ochsner Journal, 10(3), 176–178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096213/ ↵

- American Heart Association. (2000). Part 5: New guidelines for first aid. Circulation, 102(supplement 1). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.102.suppl_1.I-77 ↵

- “Cleftlipandpalate.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Cleft palate.jpg” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is licensed under CC0 1.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Bencosme, J. (2018). Periodontal disease: What nurses need to know. Nursing, 48(7), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000534088.56615.e4 ↵

- “Periodontal Disease.png” by Warren Schnider is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Bencosme, J. (2018). Periodontal disease: What nurses need to know. Nursing, 48(7), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000534088.56615.e4. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 15). Candida infections of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/index.html ↵

- “Human tongue infected with oral candidiasis.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, June 15). Candida infections of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/candidiasis/thrush/index.html ↵

- “Suspectedmethmouth09-19-05closeup.jpg” by Dozenist is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Meth mouth. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/population-health/odh/documents/meth-mouth.pdf ↵

- Edmiaston, J., Connor, L. T., Steger-May, K., & Ford, A. L. (2014). A simple bedside stroke dysphagia screen, validated against videofluoroscopy, detects dysphagia and aspiration with high sensitivity. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases: The Official Journal of National Stroke Association, 23(4), 712–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.030 ↵

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Swallowing disorders in adults. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/swallowing/Swallowing-Disorders-in-Adults/ ↵

- “Cervical lymphadenopathy right neck.png” by Coronation Dental Specialty Group is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Johns Creek (GA): Ebix, Inc., A.D.A.M.; c1997-2020. Swollen lymph nodes; [updated 2020, Aug 25; cited 2020, Sep 4]; https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003097.htm ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2015). Thinking about your thyroid. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2015/09/thinking-about-your-thyroid ↵

- “Struma 00a.jpg” by Drahreg01 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

Sample Documentation for Expected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication: Prolonged urinary retention. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. Balloon inflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient verbalized no discomfort or pain with balloon inflation or during the procedure. Peri-care provided before and after procedure. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level on bed frame. Urine drained with procedure 375 mL. Urine is clear, amber in color, no sediment. Patient resting comfortably; instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or spasms. Patient verbalized understanding.

Sample Documentation for Unexpected Findings

A size 14F Foley catheter inserted per provider prescription. Indication is for oliguria with accurate output measurements required. Procedure and purpose of Foley catheter explained to patient. Patient denies allergies to iodine, orthopedic limitations, or previous genitourinary surgeries. As the balloon was being inflated with sterile water, patient began to report discomfort. Water removed, catheter advanced one inch and balloon reinflated with 10 mL of sterile water. Patient denied discomfort after the catheter advancement. Catheter tubing secured to right upper thigh with stat lock. Drainage bag attached, tubing coiled loosely with no kinks, bag is below bladder level. Urine drained with procedure 100 mL. Urine is dark amber, noticeable sediment in tubing, with foul odor. Patient resting comfortably, denies any bladder pain or discomfort. Instructed the patient to notify the nurse if develops any bladder pain, discomfort, or urinary spasms. Patient verbalized understanding. Notify the health care provider of urine assessment. Continue monitoring patient for any new or worsening symptoms such as change in mental status, fever, chills, or hematuria.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Foley Catheter Insertion (Male).”

See Figure 21.20[1] for an image of a Foley catheter kit.

View an instructor demonstration of Male Foley Catheter Insertion[2]:

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: peri-care supplies, clean nonsterile gloves, Foley catheter kit, extra pair of sterile gloves, VelcroTM catheter securement device to secure Foley catheter to leg, wastebasket, and light source (i.e., goose neck lamp or flashlight).

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Assess for latex/iodine allergies, enlarged prostate, joint limitations for positioning, and any history of previous issues with catheterization.

- Prepare the area for the procedure:

- Place hand sanitizer for use during/after procedure on the table near the bed.

- Place the catheter kit and peri-care supplies on the over-the-bed table.

- Secure the wastebasket near the bed for disposal.

- Ensure adequate lighting. Enlist assistance for positioning if needed.

- Raise the opposite side rail. Set the bed to a comfortable height.

- Position the male patient supine with legs extended. Uncover the patient, exposing the patient’s groin, legs, and feet for positioning and sterile field.

- Apply clean nonsterile gloves and perform peri-care.

- Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Open the outer package wrapping. Remove the sterile wrapped box with the paper label facing upward to avoid spilling contents and place it on the bedside table or, if possible, between the patient’s legs. Place the plastic package wrapping at the end of the bed or on the side of the bed near you, with the opening facing you or facing upwards for waste.

- Open the kit to create and position a sterile field (if on bedside table):

- Open first flap away from you.

- Open second flap toward you.

- Open side flaps.

- Only touch the outer 1” edge of the field to position the sterile field on the table.

- Carefully remove the sterile drape from the kit. Touching only the outermost edges of the drape, unfold and place the touched side of the drape closest to linen, under the patient. Vertically position the drape between the patient’s legs to allow space for the sterile box and sterile tray. Do not reach over the drape as it is placed.

- Wash your hands and apply sterile gloves.

- OPTIONAL: Place the fenestrated drape over the patient’s perineal area with gloves on inside of the drape, away from the patient's gown, with peri-area visible through the opening. Maintain sterility.

- Empty the syringe or package of lubricant into the plastic tray. Place the empty syringe/package on the sterile outer package.

- Simulate application (do not open) of the iodine cleanser to the cotton. Place package on sterile outer package.

- Remove the sterile urine specimen container and cap and set them aside.

- Remove the tray from the top of the box and place on sterile drape.

- Carefully remove the plastic catheter covering, while keeping the catheter in the container. Attach the syringe filled with sterile water to the balloon port of the catheter; keep the catheter sterile.

- Lubricate the tip of the catheter by dipping it in lubricant and replace it in the box. Maintain sterility.

- If preparing the kit on a bedside table, place the plastic tray on top of the sterile box and carry it as one unit to the sterile drape between the patient’s legs, taking care not to touch your gloves on the patient's legs or bed linens.

- Place the top plastic tray on the sterile drape nearest to the patient.

- Tell the patient that you are going to clean the catheterization area and they will feel a cold sensation.

- With your nondominant hand, grasp the penis and retract the foreskin if present; position at a 90-degree angle. Your nondominant hand will now be nonsterile. This hand must remain in place throughout the procedure.

- With your sterile dominant hand, use the forceps to pick up a cotton ball. Cleanse the glans penis with a saturated cotton ball in a circular motion from the center of the meatus outward. Discard the cotton ball after use into the plastic outer wrap, not crossing the sterile field. Repeat for a total of three times using a new cotton ball each time. Discard the forceps in the plastic bag without touching your sterile gloved hand to the bag.

- Pick up the catheter with your sterile dominant hand. Instruct the patient to take a deep breath and exhale or “bear down” as if to void, as you steadily insert the catheter, maintaining sterility of the catheter, until urine is noted in the tube.

- Once urine is noted, continue inserting to the catheter bifurcation.

- With your nondominant/nonsterile hand, continue to hold the penis, and use your thumb and index finger to stabilize the catheter. With the dominant hand, inflate the retention balloon with the water-filled syringe to the level indicated on the balloon port of the catheter. With the plunger still pressed, remove the syringe and set it aside. Pull back on the catheter slightly until resistance is met, confirming the balloon is in place. Replace the foreskin, if retracted, for the procedure.

If the patient experiences pain during balloon inflation, deflate the balloon and insert the catheter farther into the bladder. If pain continues with the balloon inflation, remove the catheter and notify the patient’s provider.

If the patient experiences pain during balloon inflation, deflate the balloon and insert the catheter farther into the bladder. If pain continues with the balloon inflation, remove the catheter and notify the patient’s provider. - Remove the sterile draping and supplies from the bed area and place them on the bedside table. Remove the bath blanket and reposition the patient.

- Remove your gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Apply new gloves. Secure the catheter with the securement device, allowing room to not pull on the catheter.

- Place the drainage bag below the level of the bladder and attach the bag to the bed frame.

- Perform peri-care as needed.

- Dispose of waste and used supplies.

- Remove your gloves and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and periwound skin

- Signs of infection

- Pain[3]

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

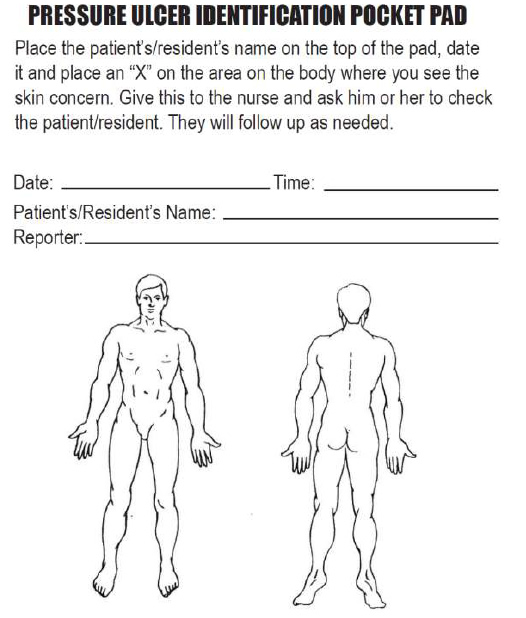

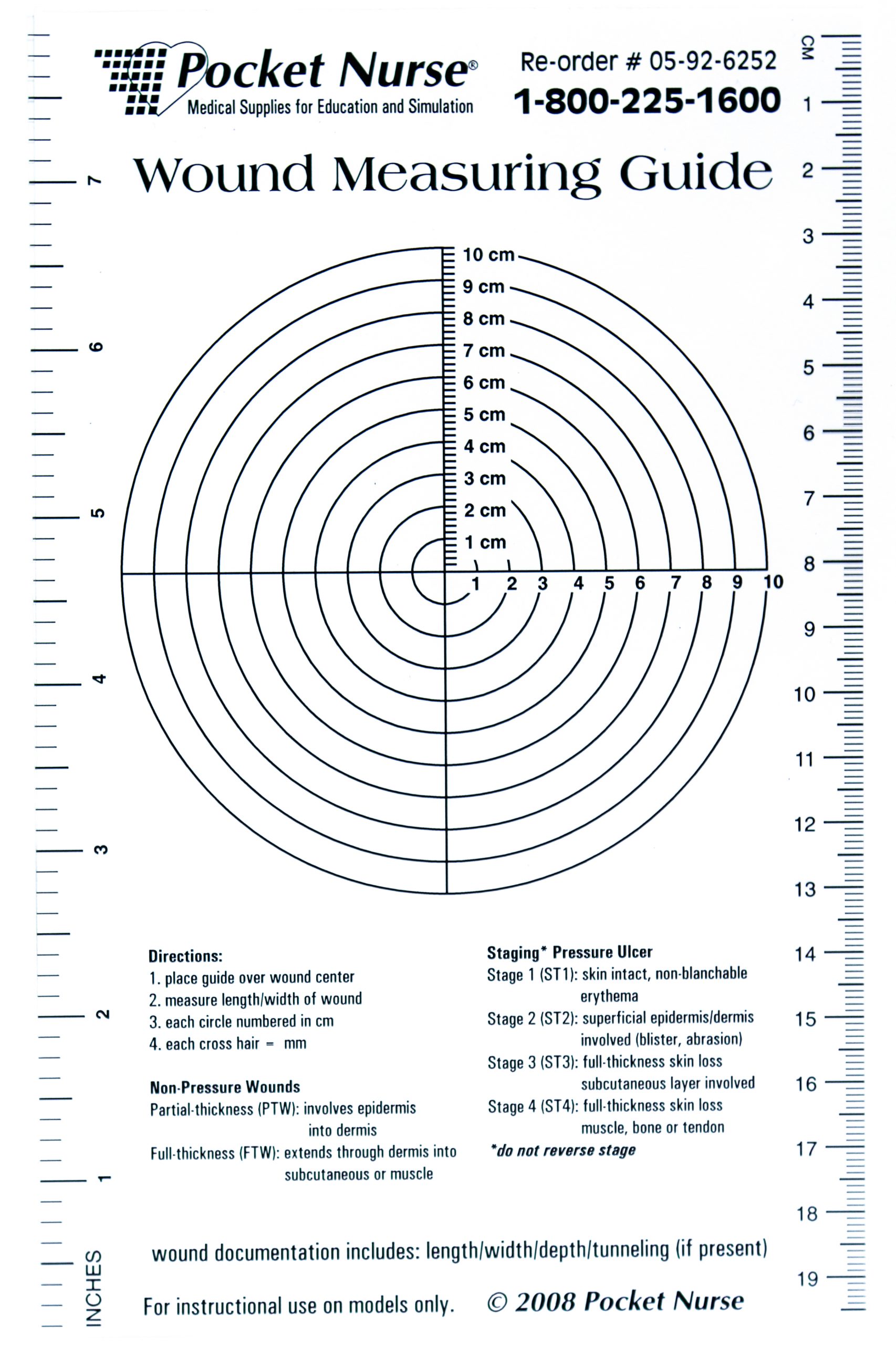

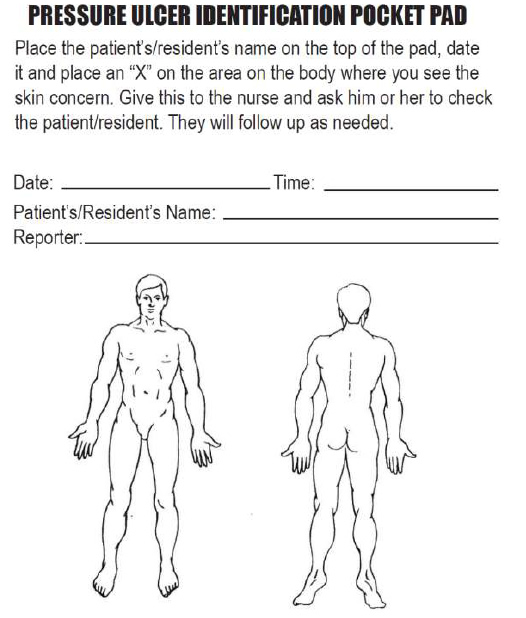

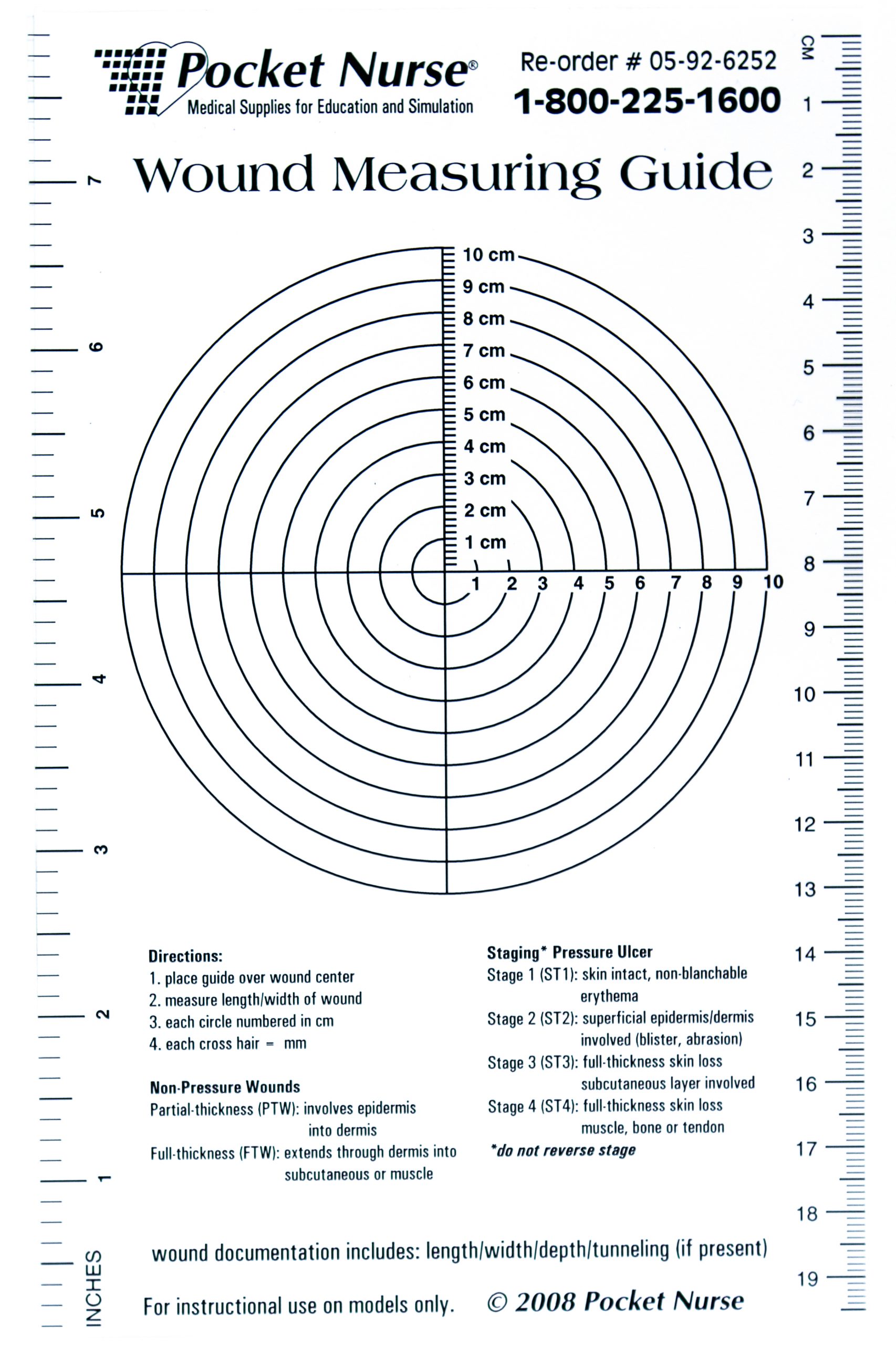

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

The location of the wound should be documented clearly using correct anatomical terms and numbering. This will ensure that if more than one wound is present, the correct one is being assessed and treated. Many agencies use images to facilitate communication regarding the location of wounds among the health care team. See Figure 20.16[4] for an example of facility documentation that includes images to indicate wound location.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Degree of Tissue Damage

It is important to continually assess the degree of tissue damage in pressure injuries because the level of damage can worsen if they are not treated appropriately. Refer to the “Staging” subsection of “Pressure Injuries” in the “Basic Concepts Related to Wounds” section for more information about tissue damage.

Wound Base

Assess the color of the wound base. Recall that healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing. Tunneling and undermining should also be assessed, documented, and communicated.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorized as scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms[5]:

- No exudate: The wound base is dry.

- Scant amount of exudate: The wound is moist, but no measurable amount of exudate appears on the dressing.

- Minimal amount of exudate: Exudate covers less than 25% of the size of the bandage.

- Moderate amount of drainage: Wound tissue is wet, and drainage covers 25% to 75% of the size of the bandage.

- Large or copious amount of drainage: Wound tissue is filled with fluid, and exudate covers more than 75% of the bandage.[6]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

- Sanguineous: Sanguineous exudate is fresh bleeding.[7]

- Serous: Serous drainage is clear, thin, watery plasma. It’s normal during the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and small amounts are considered normal wound drainage.[8]

- Serosanguinous: Serosanguineous exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.[9]

- Purulent: Purulent exudate is thick and opaque. It can be tan, yellow, green, or brown. It is never considered normal in a wound bed, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.[10] See Figure 20.17[11] for an image of purulent drainage.

Wound Size

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how consistently to measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Many facilities use disposable, clear plastic measurement tools to measure the area of a wound healing by secondary intention. Measurements are typically documented in centimeters. See Figure 20.18[12] for an image of a wound measurement tool.

Tunneling can occur in a full-thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of a tunneling can be measured by gently probing the tunneled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.[13]

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. Clock terms are also used to identify the area of undermining.[14]

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound, called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, a venous ulcer often has excess wound drainage that macerates the periwound skin, giving it a wet, waterlogged appearance that is soft and grayish white in color.[15] See Figure 20.19[16] for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localized wound infection include erythema (redness), induration (area of hardened tissue), pain, edema, purulent exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odor.[17] New signs of infection should be reported to the health care provider with an anticipated order for a wound culture.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.[18]

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and periwound skin

- Signs of infection

- Pain[19]

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

The location of the wound should be documented clearly using correct anatomical terms and numbering. This will ensure that if more than one wound is present, the correct one is being assessed and treated. Many agencies use images to facilitate communication regarding the location of wounds among the health care team. See Figure 20.16[20] for an example of facility documentation that includes images to indicate wound location.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Degree of Tissue Damage

It is important to continually assess the degree of tissue damage in pressure injuries because the level of damage can worsen if they are not treated appropriately. Refer to the “Staging” subsection of “Pressure Injuries” in the “Basic Concepts Related to Wounds” section for more information about tissue damage.

Wound Base

Assess the color of the wound base. Recall that healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing. Tunneling and undermining should also be assessed, documented, and communicated.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorized as scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms[21]:

- No exudate: The wound base is dry.

- Scant amount of exudate: The wound is moist, but no measurable amount of exudate appears on the dressing.

- Minimal amount of exudate: Exudate covers less than 25% of the size of the bandage.

- Moderate amount of drainage: Wound tissue is wet, and drainage covers 25% to 75% of the size of the bandage.

- Large or copious amount of drainage: Wound tissue is filled with fluid, and exudate covers more than 75% of the bandage.[22]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

- Sanguineous: Sanguineous exudate is fresh bleeding.[23]

- Serous: Serous drainage is clear, thin, watery plasma. It’s normal during the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and small amounts are considered normal wound drainage.[24]

- Serosanguinous: Serosanguineous exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.[25]

- Purulent: Purulent exudate is thick and opaque. It can be tan, yellow, green, or brown. It is never considered normal in a wound bed, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.[26] See Figure 20.17[27] for an image of purulent drainage.

Wound Size

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how consistently to measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Many facilities use disposable, clear plastic measurement tools to measure the area of a wound healing by secondary intention. Measurements are typically documented in centimeters. See Figure 20.18[28] for an image of a wound measurement tool.

Tunneling can occur in a full-thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of a tunneling can be measured by gently probing the tunneled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.[29]

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. Clock terms are also used to identify the area of undermining.[30]

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound, called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, a venous ulcer often has excess wound drainage that macerates the periwound skin, giving it a wet, waterlogged appearance that is soft and grayish white in color.[31] See Figure 20.19[32] for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localized wound infection include erythema (redness), induration (area of hardened tissue), pain, edema, purulent exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odor.[33] New signs of infection should be reported to the health care provider with an anticipated order for a wound culture.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.[34]

Localized damage to the skin or underlying soft tissue, usually over a bony prominence, as a result of intense and prolonged pressure in combination with shear.