Chapter 9 Human Population and Sustainability

Chapter 9 Outline:

9.1 Overview – Rapid Human Population Growth and its Effect on the Earth

9.2 Age Structure and Population Growth

9.3 Human Population Growth Variations Among Countries

9.4 Methods for Controlling Human Population Growth

9.5 Sustainability and Environmental Equity Across the Planet

9.6 Indicators of Global Environmental Stress due to Human Population Growth

9.8 Questions and Answers About Human Population Growth

9.9 Case Study: Human Population Growth

Learning Outcomes:

After studying this chapter, each student should be able to:

- 9.1 Describe how the rapid rise in human numbers has affected the earth

- 9.2 Explain how age structure of a human population affects future population growth

- 9.3 Describe the differences in human population growth among various countries

- 9.4 Describe the major ways that human population growth can be controlled

- 9.5 Identify issues related to environmental equity across the planet, and ways to measure this equity, such as the ecological (or carbon) footprint

- 9.6 Describe measurable changes (indicators) for the earth that identify its condition in relation to human populations

- 9.7 Describe how the changes wrought by humans relates to historical rates of evolutionary and ecological changes

- 9.8 Be able to answer major questions about human population growth

- 9.9 Be able to summarize the current situation regarding human population growth

9.1 Overview- Rapid Human Population Growth and its Effect on the Earth

Concepts of animal population dynamics can be applied to human populations as well. Humans are not unique in their ability to alter their environment in a way that allows for higher populations, but no other organism has made such dramatic changes to our earth and worldwide ecosystems. We have converted large areas of the terrestrial biomes to cultivated fields, covered enormous swaths of our planet with cities, homes, and businesses, and altered the very geology of our planet with dammed rivers and mining operations that have removed mountains. All of these changes have allowed for human populations to expand to unprecedented numbers, since there is enough food, clothing, and other basic necessities to populate and dramatically alter the far reaches of our planet.

Beavers are well known for their ability to alter their local environment, turning streams into ponds with their dams, allowing the beavers and many other aquatic organisms to better survive and reproduce. However, these changes are not nearly as far reaching as changes rendered by humans, and do not have the massive detrimental effects on other species that human changes have wrought.

As earth’s human population increases rapidly, so does the extraction of earth’s resources, some of which are non-renewable, such as fossil fuels. The ability of the Earth to continue to sustain this human population is in question. Long-term exponential growth of the human population carries with it the potential risks of famine, disease, extreme competition for food, water, and shelter, and the ever present risk of large-scale death. Human technology and particularly the use of fossil fuels has caused unprecedented changes to Earth’s environment, altering ecosystems and changing the atmosphere in a way that may be detrimental to all life on our planet.

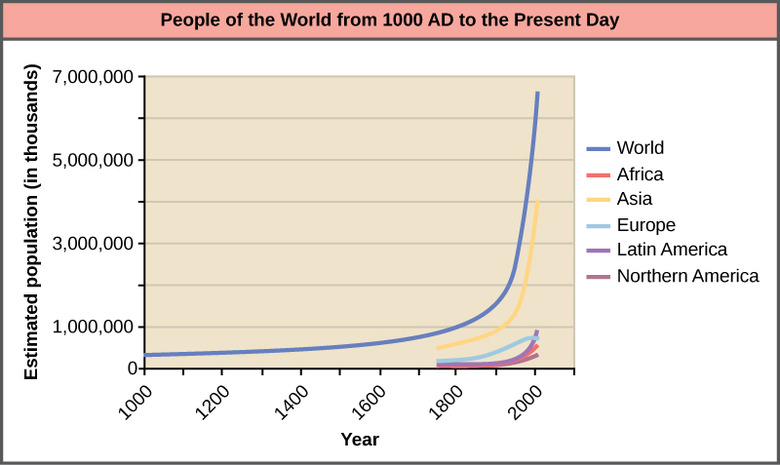

The fundamental cause of the acceleration of growth rate for humans in the past 200 years has been the reduced death rate due to changes in public health and sanitation, along with vastly more productive agricultural practices. The ability to supply humans with clean drinking water and the proper disposal of sewage and other wastes has drastically improved health in many nations. Medical innovations such as antibiotics and vaccines have also decreased mortality by infectious diseases, one limit on human population growth. Bubonic plague in the fourteenth century killed between 30 and 60 percent of Europe’s population and reduced the overall world population by as many as one hundred million people. Infectious disease continues to have an impact on human population growth, especially in poorer and less medically effective nations. The Covid-19 pandemic, although widespread sometimes tragically deadly, has not put even a detectable dent into the rapid rise in the earth’s human population. Modern science and societal actions have done much to limit the kind of dramatic loss of human life noted during the bubonic plague years. Life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa declined after 1985 as a result of HIV/AIDS mortality, but the overall human population in that region has continued its relentless rise. Figure 1 show the overall human population growth during the past 1000 years, and differences in growth rate by region of the world:

Figure 1. Changes in the human population over the last 1000 years. Both China and India have populations that have surpassed 1.4 billion, as illustrated for Asia. (Credit: OER Commons – Population and Community Ecology)

Many dire predictions have been made about the world’s human population growth leading to a major crisis called the “population explosion.” In the 1968 book Population Bomb, biologist Paul R. Ehrlich wrote, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” While these predictions were fortunately false in most parts of the world, exponential human population growth has led to suffering and deaths in resource poor areas such as sub-Saharan Africa. The population explosion continues unabated, with more people each year using the earth’s limited resources. The most populous country on earth, the People’s Republic of China, imposed a “one child policy” to help limit population growth. This policy was fairly effective, eventually slowing China’s growth rate to a manageable rate, to the point where this policy has been suspended. The availability of family planning methods, and the increase in educated and working females in other countries have both had positive effects on limiting population growth rates and increasing standards of living.

In spite of greater access to birth control methods and improvements in the education of girls (two of the most effective methods in curbing rapid population growth!) in many countries of the world , the human population continues to grow. The United Nations estimates the future world population size to be over 11 billion people by the year 2100. There is no way to know whether human population growth will moderate to the point where the crisis described by Dr. Ehrlich will be averted. Important and far-reaching consequence of population growth has been the loss of natural habitats and the degradation of the natural environment. Many countries have attempted to reduce the human impact on climate change by limiting their emissions of greenhouse gases, as formalized in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, signed by virtually every country in 2016. Although the United States backed out of this agreement under the Trump administration, based on political rather than scientific reasons, the Biden administration rejoined this agreement. We do enter the future with considerable uncertainty about our ability to curb human population growth and protect our environment.

9.2 Age Structure and Population Growth

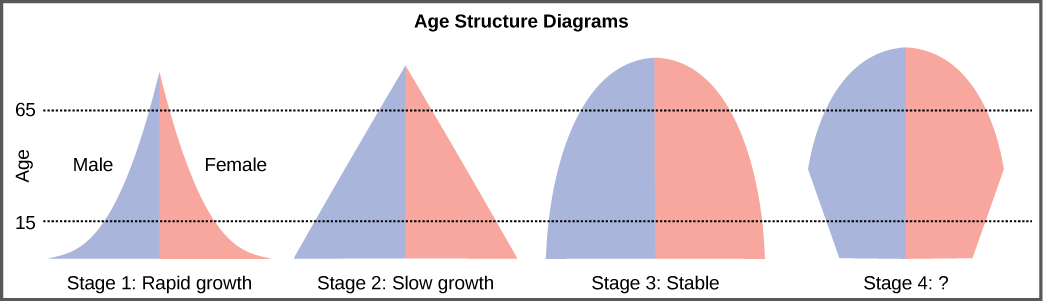

The age structure of a particular human population can be graphed in terms of the proportion of people in different age groups. This information is very informative for predicting future changes in that population. Countries with rapid population growth have a pyramidal shape in their age structure diagrams, showing a preponderance of younger individuals, most of whom will soon reach reproductive age and have more children (Figure 2). This pattern is most often observed in less developed and poorer countries where individuals often have many children, because of economic and social factors, such as the (1) lack of social security income, (2) few educational and career related opportunities for females, and (3) the lack of easily obtained birth control methods.

Age structures of areas with slow or stable growth, including developed countries such as the United States, have a less pyramidal structure, with less young and reproductive-aged individuals in proportion to older individuals. Some countries, such as Japan, Italy and Russia, have not shown an increase in population in recent years, and their population age structure is more cylindrical than pyramidal.

Figure 2. Typical age structure diagrams are shown. The rapid growth diagram narrows to a point, indicating that the number of individuals decreases rapidly with age. In the slow growth model, the number of individuals decreases steadily with age. Stable population diagrams are rounded on the top, showing that the number of individuals per age group decreases gradually, and then increases for the older part of the population. Decreasing human populations show less young people than older people (Credit: OER Commons – Population and Community Ecology)

Figure 2. Typical age structure diagrams are shown. The rapid growth diagram narrows to a point, indicating that the number of individuals decreases rapidly with age. In the slow growth model, the number of individuals decreases steadily with age. Stable population diagrams are rounded on the top, showing that the number of individuals per age group decreases gradually, and then increases for the older part of the population. Decreasing human populations show less young people than older people (Credit: OER Commons – Population and Community Ecology)

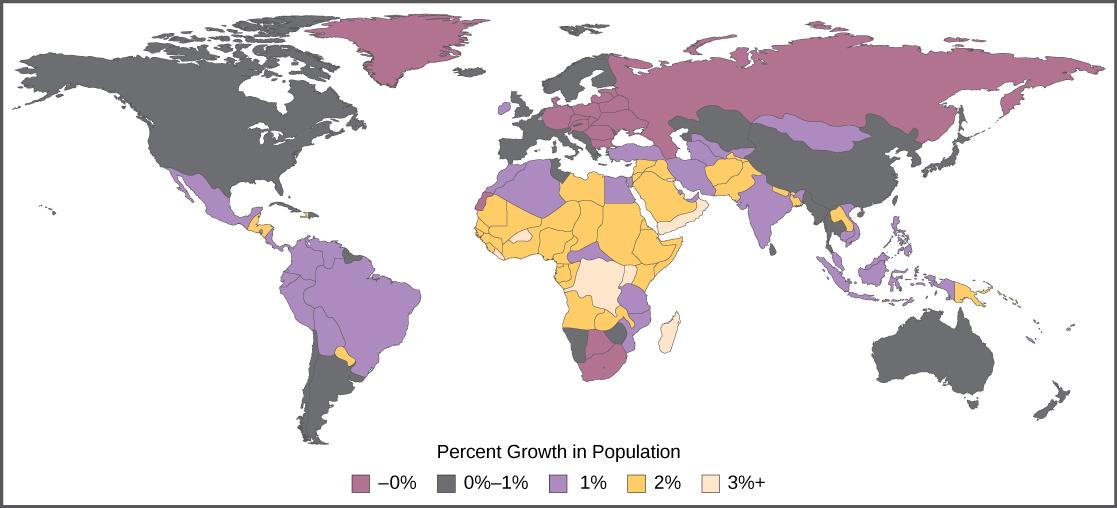

The actual growth rates in different countries are shown in Figure 3, with the highest population growth rates in less economically developed countries of Africa and Asia.

Figure 3. The percent growth rate of population in different countries is shown. Notice that the highest growth is occurring in less economically developed countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. (Credit: OER Commons – Population and Community Ecology)

Figure 3. The percent growth rate of population in different countries is shown. Notice that the highest growth is occurring in less economically developed countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. (Credit: OER Commons – Population and Community Ecology)

Link to Learning: Click through this interactive view of how human populations have changed over time

9.3 Human Population Growth Variations Among Countries

Human population growth rates are quite variable between the nations of the Earth. In general, these variations are related to economic development. With a few exceptions, most nations can be categorized into one of two groups according to their rate of population growth:

(1) The first group consists of countries which have highly developed industrial economies like Japan, Canada, USA, Australia, New Zealand, and the nations of Europe and the former Soviet Union. In these countries the rate of natural increase is less than 1% per year. The population of some of these nations are, in fact, declining (Hungary) or not growing at all (Denmark, Germany, Australia, Greece, and Italy). Finally, it is predicted by demographers that within the next few decades the majority of these nations will be experiencing zero population growth, or even a dip in total population.

(2) The second group consists of less developed nations whose rate of natural increase is greater than 1% per year. These nations are generally found in Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. The demographic graphs shown below illustrate these differences (Figure 4 ). Many African and Middle Eastern nations such as the Democratic Republic of Congo have growth rates that exceed 3.5 %. Demographers estimate that 90% or more of the increase in the world’s population over the next 50-60 years will occur in this second group of nations. As a result, world leaders and environmentalists have targeted these nations for greater control of population growth.

9.4 Methods for Controlling Human Populations

Populations stop expanding when either (a) the death rate rises to equal the birth rate, or (b) the birth rate declines to the level of the death rate. Artificially increasing death rates is not a humane approach to population control. Countries can, however, support policies to reduce their birth rates. Today, more than 90% of the world’s populations live in countries with programs to reduce birth rates. But according to the World Health organization, as of 2022, only 65% of women across the globe have the ability to utilize some form of birth control.

Demographers have generally recognized three different methods for achieving a reduction in the growth of a population. These methods are:

1. Economic Development 2. Family Planning 3. Socioeconomic Change

1. Economic Development – Demographers have noticed that economic development usually leads to a reduction in a nation’s population growth rate. This reduction is the result of many different factors that are tied to economic prosperity. In general, a higher standard of living reduces the desire for couple to have children because: (1) both sexes are usually actively engaged in the workforce (2) advanced economies offer some type of retirement income (3) the cost of raising children is high (4) children are not considered a part of the family labor force, and (5) education and employment training delays the time period when couples are able to bear children.

2. Family Planning – This method involves any program that provides educational and technological services that help individuals plan the timing of the birth of children. The nature of family planning varies from country to country because of differences in economic development, religion, and culture. Family planning has been very important in reducing birth rates in less developed countries such as China, Indonesia, Brazil, Barbados, Cuba, Columbia, Costa Rica, Fiji, Hong Kong, Jamaica, Mauritius, Mexico, Thailand, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Venezuela.

In many other less developed countries, family planning programs have not been successful because of economic, religious or cultural reasons. For example, India started to provide family planning programs beginning in 1952 when its population was about 400 million. However, these programs generally failed because of family resistance, especially from the parents of new couples, who wanted as many grandchildren as possible, and could sometimes prevent access to birth control methods. India also lacks a dependable system of social security, making children an important source of support for aging parents. The general lack of female rights, especially in rural communities, and low rates of education for girls, also made controlling family size more difficult. Lastly family planning services were greatly underfunded by state and local agencies. Since 1952 India’s population has tripled to over 1.2 billion, and unless changes occur, will probably surpass China’s large population.

Socioeconomic Changes – Some nations have used economic incentives to reduce fertility rates. China’s “one child policy” gave couples economic rewards for having fewer children. These rewards included salary bonuses, extra food, bigger pensions, improved housing, increased medical care, and free school tuition for the single child. Presently, most countries have lower taxes for families with many children, even though those children are costly to society in terms of educational and health care needs. Couples who decide not to have children or have small families pay more taxes. Changing this financial system, so that there are economic incentives to have fewer children, would encourage a more sustainable future human population.

In conclusion, the many problems related to the rapid increase in human populations can be avoided, if some or all of the above policies are put into place. For societies, these problems include a lack of food and clean water, substandard housing, high unemployment rates, traffic jams, higher rates of disease and crime, and lack of sanitary disposal of human waste. These challenges do not even begin to address the many negative effects of having so many humans on our earth’s ecosystems, including destruction of natural habitats and consequent species extinction, and the lowering of the quality of our air and water.

The following video describes changes in the human population and ways to reduce this rapid growth:

Bozeman Science (2015, Oct 8). Human Population Size [Video – YouTube]. https://youtu.be/QShgk6FrlX0

9.5 Sustainability and Environmental Equity

“Our Common Future”, a report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, published in 1987, is widely credited with having popularized the concept of sustainability, or living in a way that can be “sustained” for the foreseeable future. But for humans to live in a sustainable fashion is very difficult when human population growth increases the daily demand for earth’s limited resources.

The general idea of leaving the earth undamaged for future generations has been noted in many cultures. For example, the principle of “intergenerational equity” is captured in the Inuit saying, “We do not inherit the Earth from our parents, we borrow it from our children”. The Native American ‘Law of the Seventh Generation” states that before any major action was to be undertaken, its potential consequences on the seventh generation had to be considered. For the species Homo sapiens that at present is only 6,000 generations old, is increasing in number rapidly, and whose current political decision makers often operate on time scales of months or a few years at most, the thought that other human cultures have based their decision-making systems on time scales of many decades seems very wise.

A common current definition of “sustainable development” comes from the UN World Commission on Environment and Development: “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the orientation of the technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs.” Sustainability, therefore, refers to the sociopolitical, scientific, and cultural practices that will allow for living on this earth without significantly impairing its function for future use.

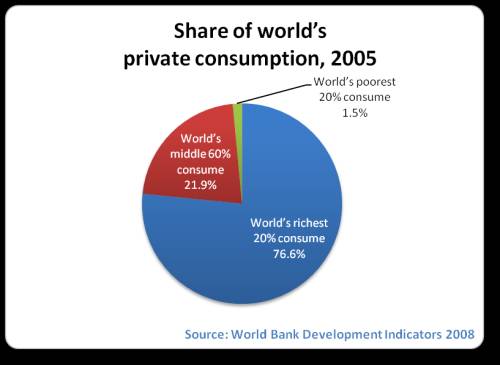

If the poorer four-fifths of the world population were to exercise their right to grow to the level of the richest one-firth, it would result in ecological devastation. So far, global income inequalities and lack of purchasing power have prevented poorer countries from reaching the standard of living (and also resource consumption and waste emission) of the industrialized countries. But countries such as China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia are catching up fast in their use of resources. If consumption must be reduced for the planet to be sustainable, who will do the reducing? Poorer nations want to produce and consume more and the economies of richer countries promote ever greater consumption-based expansion. Such stalemates have prevented any meaningful progress towards equitable and sustainable resource distribution at the international level.

Figure 5. Share of the world’s consumption of natural resources. The poorest 10% of humans accounted for just 0.5% of consumption while and the wealthiest 10% of humans account for 59% of all the consumption. (Credit: World Bank Development Indicators , 2008)

Ecological Footprint

The concept of an “ecological footprint” (EF) was developed by Canadian ecologist and planner William Rees, and uses land as the unit of measurement to assess per capita consumption, production, and the need to discharge wastes. It starts from the assumption that every category of energy and material consumption and waste discharge requires the productive or absorptive capacity of a finite area of land or water. If we add up all the land requirements for all categories of consumption and waste discharge by a defined population, the total area needed represents the Ecological Footprint of that population (whether or not this area coincides with the population’s home region!).

Land is used as the unit of measurement for the simple reason that, according to Rees, “Land area not only captures planet Earth’s finiteness, it can also be seen as a proxy for numerous essential life support functions from gas exchange to nutrient recycling … land supports photosynthesis, the energy conduit for the web of life. Photosynthesis sustains all important food chains and maintains the structural integrity of ecosystems.” Ecological footprint analysis can tell us in a vivid, ready-to-grasp manner how much of the Earth’s environmental functions are needed to support human activities. This analysis also makes visible the extent to which consumer lifestyles and behaviors are ecologically sustainable.

Using the idea of ecological footprint, it has been calculated that the average American needs (conservatively) 5.1 hectares per capita of productive land. If the current global population were to adopt American consumer lifestyles, we would need at least three additional planets to produce the resources, absorb the wastes, and provide general life-support functions to allow the world’s population to function like an American! (with 7.4 billion hectares of the planet’s surface available for human consumption).

While much progress is being made to improve the efficiency of resource use, far less progress has been made to improve resource distribution across the planet. Currently, just one-fifth of the global population is consuming three-quarters of the earth’s resources, as shown by the distorted sizes of various countries (based on resource use) in Figure 6. This illustration shows graphically how regions of the world differ in their per capita ecological footprint.

Figure 6. World-wide patterns in resource consumption by country or region. Country sizes are enlarged or shrunken, based on amount of resource use. This map is based on per capita ecological footprints, a common measure of human demand on the earth’s ecosystems. (Source: Geography – WorldPress.com)

The precautionary principle is an important concept in environmental sustainability. A 1998 consensus statement characterized the precautionary principle this way: “when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically”. For example, if a new pesticide chemical is created, the precautionary principle would dictate that we presume, for the sake of safety, that the chemical may have potential negative consequences for the environment and/or human health, even if such consequences have not been proven yet. In other words, it is best to proceed cautiously in the face of incomplete knowledge about something’s potential harm. In the same way, it is possible to note some of the indicators of global environmental stress, caused by the current human population of over 8 billion people

9.6 Indicators of Global Environmental Stress due to Human Population Growth:

Forests – Deforestation remains a major issue. Over one million hectares of forest have been lost every year in the last few decades. The largest losses of forest area are taking place in the tropical moist deciduous forests, a zone with some of the poorest communities on earth with high rates of human population growth. Recent estimates suggest that nearly two-thirds of tropical deforestation is due to farmers clearing land for agriculture. There is increasing concern about the decline in forest quality associated with intensive use of forests and unregulated access for damaging activities such as gold mining (Figure 7).

Figure 7. An aerial view shows a deforested area during an operation to combat deforestation near Uruara, Para State, Brazil, Jan. 21, 2023. (Credit: Voice of America – Climate Change – Steve Baragona)

Soil – As much as 10% of the earth’s vegetated surface soil is now at least moderately degraded. Trends in soil quality and management of irrigated land raise serious questions about longer-term sustainability. It is estimated that about 20% of the world’s 250 million hectares of irrigated land are already degraded to the point where crop production is seriously reduced. As human populations continue to increase, more land is coming under cultivation, with further risks of degradation.

Fresh Water – Some 20% of the world’s population lack access to safe water and 50% lack access to safe sanitation, a situation that becomes more problematic as human populations increase. If current trends in water use persist, two-thirds of the world’s population could be living in countries experiencing moderate or high water stress in the near future, especially as climate change increases temperatures and reduces precipitation in areas of the world.

Marine fisheries – Over 25% of the world’s marine fisheries are being fished at their maximum level of productivity and 35% are overfished at an unsustainable rate (yields are declining). In order to maintain current per capita consumption of fish with a rising global human population, fish harvests must be somehow increased. Much of this needed increase might come through aquaculture which is a known source of water pollution, wetland loss and mangrove swamp destruction.

Biodiversity — Biodiversity is increasingly coming under threat from development as human populations expand in area, degrading or destroying natural habitats. Pollution from a variety of sources can also reduce biodiversity. A comprehensive global assessment of biodiversity put the total number of species at close to 14 million and found that between 1 – 11% of the world’s species may be threatened by extinction. Coastal ecosystems, which host a very large proportion of marine species, are at great risk with 30% of the world’s coasts at high potential risk of degradation and another 17% at moderate risk.

Atmosphere – The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has established that human activities are having a discernible influence on global climate, warming the earth as more greenhouse gases are released from an increasing human population. Carbon dioxide emissions in most industrialized countries have risen during the past decades and countries have generally failed to stabilize their greenhouse gas emissions, despite efforts to do so.

Toxic chemicals – About 100,000 chemicals are now in commercial use and their potential impacts on human health and ecological function represent largely unknown risks. Persistent organic pollutants released by a rising human population are being widely distributed by air and ocean currents – they are found in the tissues of people and wildlife everywhere, even in artic regions and Antarctica. These pollutants are of particular concern because of their high levels of toxicity and persistence in the environment.

Hazardous wastes – Pollution from heavy metals and other hazardous wastes, especially from their use in industry and mining, is also creating serious health consequences and ecological damage in many parts of the world. This is especially true as developing countries with ever larger populations seek new economic opportunities. Incidents and accidents involving uncontrolled radioactive materials continue to increase, and particular risks are posed by the legacy of contaminated areas left from military activities involving nuclear materials.

Domestic and Industrial Waste — Domestic and industrial waste production continues to increase in both absolute and per capita terms as world populations rise. In the developed world, per capita waste generation has increased threefold over the past 20 years, In developing countries waste generation will likely double during the next decade. The level of awareness regarding the health and environmental impacts of inadequate waste disposal remains rather poor. Inadequate sanitation and a general lack of waste management infrastructure is still one of the principal causes of death and disability for the urban poor.

9.7 Taking The Long View: Human Population Growth and Sustainability from an Evolutionary and Ecological Perspective

Of the different forms of life (species) that have inhabited the Earth in its 4.5 billion year history, 99.9% are now extinct. Against this backdrop, the rise of humans with a roughly 200,000-year history barely merits attention. As the American novelist Mark Twain once remarked, “If our planet’s history were to be compared to the Eiffel Tower, human history would be a mere smear on the very tip of the tower”.

But while modern humans (Homo sapiens) might be insignificant in geologic time, we are by no means insignificant in terms of our recent planetary impact. Over 40% of the product of terrestrial plant photosynthesis – the basis of the food chain for most animal and bird life – is being appropriated by humans for their use. In addition, over 25% of photosynthesis on continental shelves (coastal areas) is ultimately being used to satisfy human demand. An ever expanding population of humans has appropriated natural resources to an extent that is having profound impacts upon the wide diversity of other species that also depend on them.

Evolution normally results in the generation of new lifeforms at a rate that outstrips the extinction of other species, resulting in continued biological diversity. However, scientists have evidence that, for the first observable time in evolutionary history, one species – Homo sapiens – has upset this balance to the degree that the rate of species extinction is now estimated at 10,000 times the rate of species renewal. Human beings, just one species among millions, are crowding out the other species we share the planet with. Evidence of human interference with the natural world is visible in practically every ecosystem from the presence of pollutants in the stratosphere to the artificially changed courses of the majority of river systems on the planet. It is argued that ever since we abandoned nomadic, gatherer-hunter ways of life for settled societies some 12,000 years ago, humans have continually manipulated their natural world to meet their needs. While this observation is a correct one, the rate, scale, and the nature of human-induced global change — particularly in the post-industrial period — is unprecedented in the history of life on Earth.

There are three primary reasons for this human induced global change:

(1) Mechanization: First, mechanization of both industry and agriculture in the last century resulted in vastly improved labor productivity which enabled the creation of goods and services. Since then, scientific advance and technological innovation – powered by ever-increasing inputs of fossil fuels and their derivatives as populations increased – have revolutionized every industry and created many new ones. The subsequent development of western consumer culture, and the satisfaction of the accompanying disposable mentality, has generated material flows of an unprecedented scale. The Wuppertal Institute estimates that humans are now responsible for moving greater amounts of matter across the planet than all natural occurrences (earthquakes, storms, etc.) put together.

(2) Size of Human Population. The sheer size of the human population is unprecedented. Every passing year adds another 100 million people to the planet. Even though the environmental impact varies significantly between countries (and within them), the exponential growth in human numbers, coupled with rising material expectations in a world of limited resources, has catapulted the issue of distribution to a prominent position. Global inequalities in resource consumption and purchasing power mark the clearest dividing line between the haves and the have-nots. It has become apparent that present patterns of production and consumption are unsustainable for a global population that is projected to reach between 12 billion by the year 2050. If ecological crises and rising social conflict are to be countered, the present rates of over-consumption by a rich minority, and under-consumption by a large majority, will have to be brought into balance.

(3) Chemicals and Materials. Beyond the rate and the scale of change is the nature of that change, which is unprecedented. Human inventiveness across the globe has introduced chemicals and materials into the environment which either do not occur naturally at all or do not occur in the ratios in which we have introduced them. These persistent chemical pollutants are believed to be causing alterations in the environment, the effects of which are only slowly manifesting themselves, and the full scale of which is beyond calculation. CFCs and PCBs are but two examples of the approximately 100,000 chemicals currently in global circulation. (Between 500 and 1,000 new chemicals are being added to this list annually.) The majority of these chemicals have not been tested for their toxicity on humans and other life forms, let alone tested for their effects in combination with other chemicals. These issues are now the subject of special UN and other intergovernmental working groups.

The following video provides ways that our current population can attempt to live more sustainably:

9.8 Human Population – Some Questions and Answers

1, Why is human population an important topic?

The human race has an enormous impact on this planet! We control and modify the Earth more than any other species. How do we meet the needs of human beings and also preserve Earth’s finite resources, biodiversity, and natural beauty? This is the fundamental question of our time, and the challenge is becoming more problematic as we add more people. Meanwhile, in every locality, it’s important to know how fast the human population is growing, so that we can build sufficient sewers, roads, power plants, and schools.

2. Do we know exactly how many people there are in the world today?

No. There are so many people on this planet that counting them up, exactly, is impossible. However, experts believe there are more than 8.1 billion people in the world today. This is a fairly reliable estimate. World population in 2017 is more than 2 times greater than it was in 1960,4 times greater than 1900, and 10 times greater than 1700. After growing very slowly for tens of thousands of years, world population has grown very rapidly in the last few centuries and continues to do so.

3. How fast is the world’s population growing?

In terms of net gain (births minus deaths), we are adding over 200,000 people to this planet every day (which equates to 140 more people EVERY MINUTE). That equates to 70 million more people every year, about the same as the combined population of California, Texas, and New York. Although we have made encouraging progress in slowing the growth rate, any rate of growth is unsustainable in the long term, so we must stabilize the human population soon for the good of future generations.

4. Are there any parts of the world where the human population is not growing?

Yes. Roughly speaking, populations are holding stable in Japan, Western Europe, and North America. Populations are decreasing somewhat in Russia and some Eastern European countries. But the human population is growing either rapidly or very rapidly in almost every other part of the world right now, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, South and Central America and most of the Middle East and Africa. In other words, human populations have stabilized where about 2 billion people live and are still increasing very rapidly where 5 billion people live – those who can least afford it. Result: the annual net gain of over 70 million people!

5. I have heard some say the world population crisis is over and that it’s not a problem anymore. Is this true?

No, absolutely not. First of all, 8.1 billion people may well be too many already. Cornell University professor David Pimentel’s research shows that about 2 billion people is the number the planet can sustainably support, if everyone consumes the same amount of resources as the average European (which is less than the average American). Secondly, U.N. experts predict that world population will increase for at least the next 50 years, with a “most likely” prediction of 10 billion people by the year 2050. There probably will be additional growth beyond that.

There’s no doubt that the worldwide average number of children per woman has come down tremendously over the last 50 years – from more than 5 children per woman to about 2.5 per woman. However, (1) the current average is still well above replacement level, which would be 2.1 children per woman, and (2) the number of women having children is about TWICE what it was in 1960. There is also huge “demographic momentum,” since half the world’s population is age 24 or younger – either having children now, or poised to have them in the next 10 to 15 years – so that any changes we make today may not have a visible effect until a generation has passed!

Finally, people are living longer all over the world and will continue to do so, with a resultant slowdown in death rates. Thus, there’s a big imbalance in the birth to death ratio: currently about 5 births for every 2 deaths worldwide.

6. So much of the world is still empty space – can’t people just move to less crowded places?

A lot of that space isn’t empty: vast tracts of farmland are necessary to feed the people who live in cities and towns, and forests are necessary to produce wood and oxygen. Much of the land that hasn’t been settled by people simply isn’t habitable: it’s too dry, too cold, or too rocky. Besides, the people who are most overcrowded are struggling to exist on less than a dollar a day… they don’t have the money to move!

7. The United States and other countries with low birth rates let in millions of immigrants each year. Doesn’t this act as a “safety valve” to relieve the population pressure of the faster-growing countries?

Not really. Think of it this way. Each year the U.S. currently allows about a million people to immigrate legally (About 0.5 to 1 million come in illegally.) But each year most countries of the developing world add almost 70 million more people to their numbers, net gain! The one to two million coming into the U.S. hardly makes a dent to relieve the crushing problems created by the almost 70 million more people into these resource-stressed countries – each year!

If we continue letting in as many immigrants for the next 50 years as we have for the past 25, we will absorb only about 4 percent of the population growth from the less-developed countries! Although migration can greatly improve the lives of the immigrants themselves, it is not an effective way to relieve the population growth of the countries they come from.

8. I’ve heard that as population growth slows, countries like the U.S. are going to have to support increasing numbers of dependent elderly people. Don’t we need to have more kids and increase immigration so that we’ll have enough workers to support all these retired people?

No. First of all, people are dependent in their retirement years for only a fraction of the time they’re dependent in their childhood. Right now retirement lasts only half as long as the dependent period before a young person enters the workforce. If trends continue, it may decrease to a third or even a quarter of that youthful dependency. So children are far more expensive to the economy than the elderly! Secondly, population growth has to stop sooner or later, so bringing in more people is not a long-term solution. The long-term solution is to restructure our system so that we don’t need a constant influx of more people. The sooner we stop the increase in numbers, the more intact we leave our resource base for our children of the future.

9. What is meant by “humane” population stabilization?

Controlling birth rates is humane and helpful for families. Population continues increasing because the death rate worldwide dropped much farther than the birth rate. Of course no one wants to see death rates rise. That would be an unthinkably inhumane way to stop population growth! The humane way to reduce population growth is for birth rates to drop and balance with today’s lower death rates. Repeated studies in countries all around the world show that the longer children stay in school, the fewer children they will have. Smaller families can provide more resources for each child, and entire nations benefit when they have fewer children to drain their limited, declining resources. So education is the key to humane population stabilization. (Figure 8)

One highly successful educational approach involves the use of specially-created soap operas, both on TV and radio that communicate – even to illiterate people – the benefits of having fewer children. These special soaps are currently running on every continent (except Antarctica) and are having an incredible impact to help reduce people’s expectations about their “desired family size.”

Figure 8. Family sizes vary but giving all couples the ability to plan their desired family size is an important factor in reducing overall human population growth. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

9.9 Case Studies in Human Population Growth

The growth in our planet’s human population can be mind boggling. Twelve thousand years ago there were about four million humans across the entire planet, less than the current population of Maricopa County in central Arizona. In 1803, the human population reached its first billion. More recently, we have been adding about a billion people to the planet every 12 years. In 2024 the number of humans is about 8.1 billion and continues to rise.

When the People’s Republic of China was approaching a population of one billion in 1979, an official government policy was put into place that limited families to one child (Figure 9). Even with this policy in place, the country added almost a half billion more people between 1979 and 2019. This is because in 1979 most families had many children, and as these children went through their reproductive years, the one child from each family still added to the total number. But this increase was about 400 million less than what would have happened without the one-child policy. As population growth began to level off in recent years, the rules were relaxed to allow 2 children per family.

Figure 9. Poster promoting the “one child” policy in the People’s Republic of China. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Most countries do not have the political and social will to impose such a policy to limit population growth. Yet in many developed countries, such as Japan, Germany, and Italy, population size has stabilized. Many relate this change to social factors, such as the preponderance of both men and women in the workforce, the decrease in marriages, and the generally higher level of education that women have achieved today. The developed countries of the world have fairly stable populations, and do not generally add to world population growth.

In many countries that are making the change from “developing” to “developed”, such as South Korea, Brazil, and Mexico, population growth rates have decreased as well. Most attribute this to several factors, such as greater educational and career opportunities for women, better systems of social security for retirees so that large families are not needed economically, and easier access to family planning methods. Although the populations of these countries continue to grow, the trend is toward smaller and smaller families. Educating girls as long as possible is closely tied to reduced family sizes.

Today the greatest population growth is noted in some of the poorest countries of the world, primarily in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia. These areas have the lowest levels of education for girls, have cultures that encourage large families and discourage women from working, lack forms of social security for older adults (who must then depend on their family), and often ban or greatly limit birth control methods. Many of these countries, such as Sudan, Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, and Yemen, have populations suffering from starvation already, with limited resources to feed their burgeoning populations.

Counterintuitively, many aid organizations have been working hard to immunize babies and lower the childhood death rate. Although this might seem like it just exacerbates the population problem, studies have shown that women are more willing to have smaller families if they can be more sure that their children will survive to adulthood.

How will human population growth change in the future? Will growth continue until the carrying capacity for humans is exceeded, resulting in starvation, suffering and death? Some biologists point with hope to the lowering of the human population growth rate overall, believing that if this trend continues populations may level off. But most also note that unless social, pollical, and cultural practices change in the near future, many of the earth’s poorest countries are on the way to severe population challenges, with more people than available food and other essential resources.

Attribution

Content in this chapter includes original work created by Lauren Roberts and Paul Bosch as well as from the following sources, with some modifications:

“Biology, 2nd edition” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 / A derivative from the original work

Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from the original by Matthew R. Fisher.