44 4.6 POLICY STREAMS AND “WINDOWS” OF OPPORTUNITY

- POLICY STREAMS AND “WINDOWS” OF OPPORTUNITY

John Kingdon was working on health care and transportation policy for the federal government in the 1970s and 80s when he observed a pattern in the way that topics came to the attention of policy makers. Kingdon proposed three “streams” that must unite for a “policy window” to open and place a potential policy on the public agenda. The model that Kindgon created, called the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF), continues to be an influential model in policy literature. While the MSF was primarily developed to better explain how policy problems and solutions attain prominence during the agenda setting process (Kingdon, 2011), MSF is also considered a stand-alone theory of policy making and often compared to the stages heuristic model discussed in chapter 3.

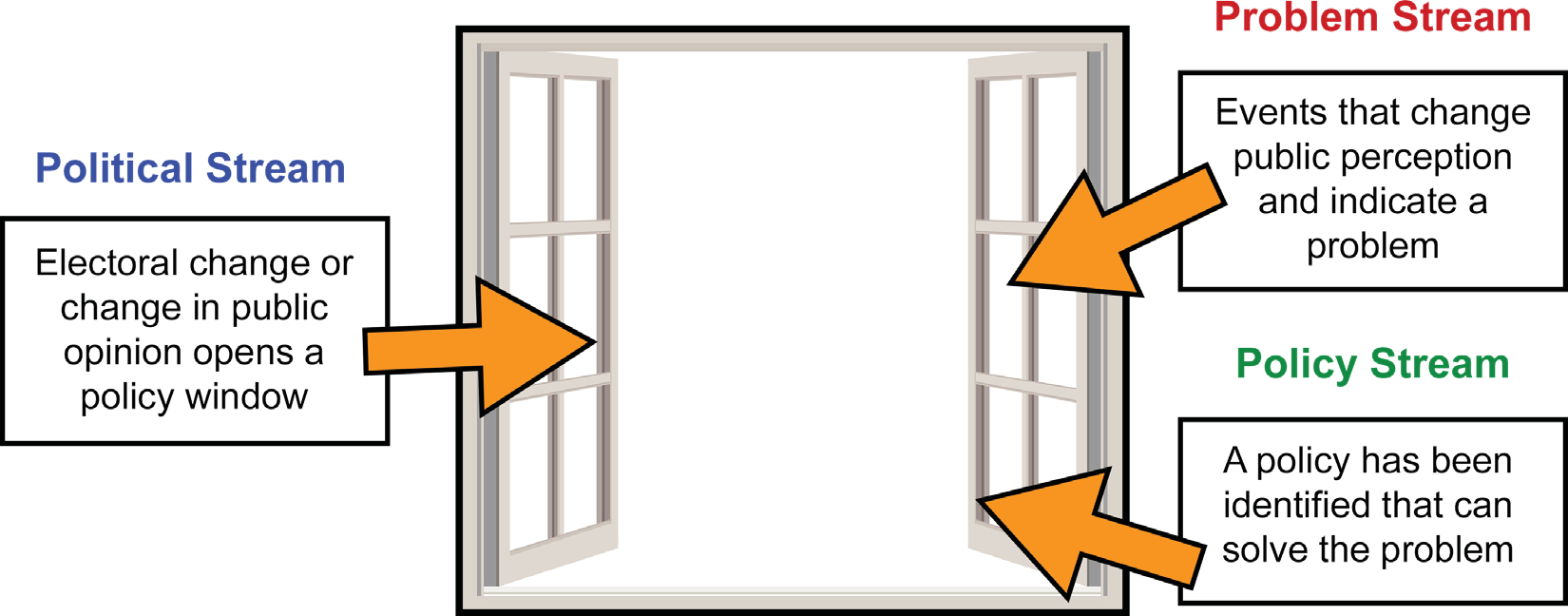

If the context aligns and a policy idea has support from policymakers, the issue is considered “ripe” for a policy solution (Kingdon, 2003; Stewart, Hedge, Lester, 2008). How do we know when a policy is “ripe?” John Kingdon (2011) argues that three conditions must be satisfied before an idea gains traction. He describes these conditions as the three “streams” of the agenda setting process: (1) the problem stream, (2) the policy stream, and (3) the political stream. If the conditions laid out in the various streams are met, a brief “window of opportunity” will open, and the policy has a greater likelihood of becoming law. However, policy windows only stay open for a short time: “If participants cannot or do not take advantage of these opportunities, they must bide their time until the next opportunity comes along” (Kingdon, 2003).

The problem stream is an event that changes our perception of a problem and indicates that something is wrong. For instance, employment rates may drop, crime rates increase, or doctors begin to notice a sudden increase in the number of people becoming sick from vaping. The statistical data connected to the previous examples are considered indicators. Extreme fluctuations in common indicators suggest that a problem is forthcoming, and government action may be necessary. For example, analysts in the financial sector began to see alarming trends in foreclosure rates that eventually led to the 2008 recession. In the early 2000s, doctors began to report an increase in deaths due to opioid addiction. In both instances, changes over time to financial and medical indicators resulted in increased attention from policymakers. In the case of the financial crisis, legislation was passed to regulate the banking industry.

Not every fluctuating indicator will lead to public policy. Often statistical changes go ignored or are not deemed significant enough for action. Instead, “interest groups, government agencies, and policy entrepreneurs use these numbers to advance their preferred policy ideas” (Birkland, 2018). Sometimes they are successful, and sometimes they are not. As mentioned, government simply does not have the ability to address every problem.

While indicators typically illustrate slow changes, focusing events are “sudden and rare events that spark intense media and public attention because of their sheer magnitude or because of the harm they reveal” (Birkland, 2018). Events such as the September 11 attacks, violent protests and rallies, a nuclear disaster, an oil spill, or an unexpected epidemic can all trigger action from policymakers. At the very least, such events cause public outcry and embolden the public to pay more attention to undiscovered issues.

When Hurricane Katrina made landfall as a category 5 hurricane in 2005, it quickly became apparent that all levels of government (local, state, and federal) were woefully unprepared for such levels of devastation. As a result of Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), along with state and local emergency services, have undergone numerous changes. New technology and procedures were adopted to quickly and efficiently connect state and local first responders. Also, Congress gave FEMA greater authority to move resources before a storm rather than wait until other government levels request aid (Roberts, 2017).

When Hurricane Katrina made landfall as a category 5 hurricane in 2005, it quickly became apparent that all levels of government (local, state, and federal) were woefully unprepared for such levels of devastation. As a result of Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), along with state and local emergency services, have undergone numerous changes. New technology and procedures were adopted to quickly and efficiently connect state and local first responders. Also, Congress gave FEMA greater authority to move resources before a storm rather than wait until other government levels request aid (Roberts, 2017).

Kingdon’s policy stream includes any proposals that have been developed to address a particular issue (Stewart et al., 2008). Customarily, the policy stream consists of a viable policy option or even concrete legislation, but it can also incorporate technology or even public perception. For example, immigration reform is a frequent topic on the public agenda. Immigration experts and lawmakers have considered various solutions to curb illegal immigration including building a wall on the southern border, reforming the Visa system, aiding South American countries to improve their economy and fight crime, and even closing the border or canceling such immigration programs as the Diversity Immigrant Visa. However, aside from efforts to obtain support from Congress to build a border wall, Congress has not proposed any policy options to reform the current immigration system. As the debate surrounding immigration reform has become exceptionally partisan in nature, proposed policy options are unlikely to gain support from both parties.

The final stage in the policy streams approach is the political stream. The political stream comes into play when electoral change or change in public opinion leads to reform. For instance, a change in political regime or increasing support for an issue can generate conditions favorable for policy change. President Trump came into office promising tax reform, including measures to simplify the tax code. With a Republican majority in both chambers of Congress, the President was able to pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Likewise, changes in public opinion can also influence the political stream. Public support for same-sex marriage is a good example of public opinion galvanizing policy changes. A 2010 Gallup Poll found that only 44% of adults supported same-sex marriage. In roughly five years, the number of supportive adults increased from 44% to over 60%. Increased public support for same-sex marriage led to legalization in individual states prior to the Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) that expanded the right to all fifty states (Pew Research).

Do policymakers use public opinion to guide their decisions and actions?

The rather complicated answer is, sometimes. For example, the public became outraged after it was revealed that migrant children were held without their parents in deten- tion centers across the southern U.S. border. At the height of public con- troversy over child separations, polls from CBS, CNN, and Quinnipiac Uni- versity found that 66% of Americans opposed the separations (Smith and Phillips, 2018). The combination of public outcry and negative public opinion led President Trump to sign an executive order that ended the practice of child separation.

The rather complicated answer is, sometimes. For example, the public became outraged after it was revealed that migrant children were held without their parents in deten- tion centers across the southern U.S. border. At the height of public con- troversy over child separations, polls from CBS, CNN, and Quinnipiac Uni- versity found that 66% of Americans opposed the separations (Smith and Phillips, 2018). The combination of public outcry and negative public opinion led President Trump to sign an executive order that ended the practice of child separation.

Figure 4.3: Kingdon’s Policy Streams and Windows of Opportunity

Source: Original Work Attribution: Kimberly Martin License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Gerston (1997) argues that the scope and intensity of public support determine whether a policy issue comes to the attention of policymakers. When taking into account scope, policymakers consider how widespread the problem has become. According to Gerston, “If only a small percentage of the population is worried, then the issue will fail the scope test because of its inability to generate enough attention” (Gerston, 1997). This does not mean that a small group cannot get an item on the agenda; it simply means that issues that reach the broader public consciousness are more likely to attract immediate attention. Likewise, intensity refers to the strength and depth of reactions from the public. Is the public’s response to a problem lukewarm and disinterested, or are protestors lining the streets and calling congressional offices? It will come as no surprise that the issue with protestors lining the streets will receive more immediate attention from policymakers.

Alternatively, many examples exist in which the scope and intensity of the American public’s opinions on an issue were highly supportive yet Congress still failed to act. The ongoing debate surrounding gun control is one of those issues. A 2019 Gallup poll found that 63% of American adults believe that laws covering the sale of firearms should be “more strict.” Moreover, policies such as universal background checks have garnered over 90% support; however, this support does not necessarily translate into actual policy (Cohn & Sanger-Katz, 2019).

Gerston (1997) also notes that intensity is not always enough to draw the attention of lawmakers. Sometimes the duration of the intensity determines whether a policy will make it onto an agenda. As with most focusing events, support for gun control measures increases after mass shootings (Gallup Poll, 2018). While support for stricter laws remains steady, after a shooting such as the one in Parkland, Florida, or El Paso, Texas, public support for new laws can spike by up to 20% (New York Times, 2019). However, public interest generally fades within a month of a mass shooting event (Parker et al., 2017). You will recall from earlier chapters, and your American government courses, that the policy process takes time and effort. If interest fades while legislation meanders through the process, it takes the pressure off policymakers to follow through with legislation that aligns with public opinion. Often interest groups and activists create strategies to maintain public pressure because they know that increased public support over long periods will more likely lead to success (Gerston, 1997).

Finally, resources determine whether an issue will generate more or less attention. Policy problems that cost more to fix will generate more attention than will less costly problems (Gerston, 1997). Consider the debates surrounding health care and education spending. Congressional proposals for universal health care or free college education are regularly met by critics who argue that the cost to implement these policies is simply too high. High costs do not automatically prevent policies from being enacted, but supporters will need to craft an argument that highlights the beneficial outcomes of the program over the costs. In the end, if a public problem receives widespread attention, generates an intense reaction, keeps the public’s attention for a long period of time, and has identified resources to support a solution, the problem has a much greater chance of ending up on the agenda.