56 5.3 – INPUTS, OUTPUTS, AND OUTCOMES

INPUTS, OUTPUTS, AND OUTCOMES

Policymakers can and do improve efficiency in public programs by applying measures that were once thought of use only to private businesses. Increases in productivity are useful to both the public and private sectors and can be determined by measuring policy outputs in relation to the resources used to achieve those outputs. Does productivity always lead to efficiency in public policy? Policymakers can apply what scholars refer to as a results chain logic model as a guide to identifying the components of a successful policy. A results chain model is a “linear process with inputs and activities at the front and long-term outcomes at the end” (Funnell & Rogers, 2011). Developing these benchmarks makes it much easier to assess whether a policy is implemented correctly, is meeting desired goals, or needs adjustments or changes.

Inputs are resources dedicated to a policy or public program. These could be money, staff, facilities, time, or anything of value that provides the foundation for the policy to function. Students can learn to apply the results chain logic model through the input outcomes “sandwich” example. For this example, imagine you are hungry and that your goal is to construct a sandwich. Inputs would include any- thing you might use to make a sandwich: two slices of bread, cheese, turkey, lettuce, tomato, and/or mustard. Activities are actions taken by implementers and policymakers to meet policy objectives. Activities are what implementors do with the inputs to fulfill the policy’s mission. The activities required to make a sandwich are straightforward. Put one piece of bread on a plate and add the desired amount of toppings, then add the remaining piece of bread. Outputs are “the immediate, easily measurable effects of a policy, whereas outcomes are the ultimate changes that a policy will yield” (Tieghi, 2017). Outcomes also convey the benefits the policy is designed to deliver. The immediate, and obvious, outputs of sandwich making are that a sandwich is now made. The outcomes are where the actual effects of creating a sandwich begin to take shape. Now that a sandwich is created, it can be eaten, and the person who eats it is no longer hungry; because their body receives nourishment, they can continue their day. The impacts are the higher-level goals and long-term consequences of a policy that lead to mea- surable improvements in people’s lives. The person who has eaten the sandwich can now contribute more fully to society or excel at their job or school because they are no longer hungry. Perhaps they will go on to produce new or innovative policies themselves now that their bodies are nourished and minds have been fed. And to think, all these amazing things happened because someone decided to make a sandwich!

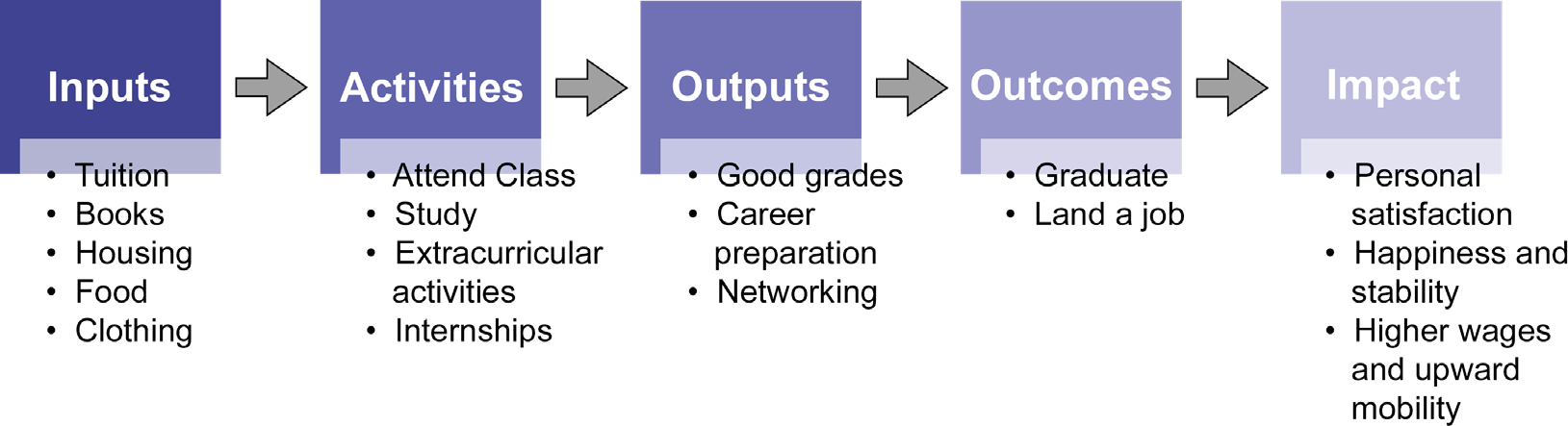

This humorous example is simplistic in its design but a valuable way to emphasize the results chain process. Students can easily apply the results chain to their own experiences. For instance, most students would claim the outcome of their college career is to graduate and obtain a well-paying job. The logic model in Figure 5.2 outlines that process. Inputs are all the resources the student puts into obtaining a college degree, such as tuition, books, and housing costs.

Students must attend class and study to receive good grades and prepare for the workforce. The outcome may be to graduate, but the impact of years of hard work is much broader. Students who graduate from college are more likely to achieve financial stability, gain a sense of personal satisfaction and happiness, and become a more productive citizen overall (Carnevale et al., 2016).

Figure 5.2: Results Chain Logic Model Applied to College Degree Attainment

Source: Original Work Attribution: Kimberly Martin License: CC BY SA 4.0

The results chain can be applied to a wide range of policy issues. Designing ef- ficient public policy requires the same level of planning and dedication as that used to create the results chain model. However, policymakers often make the mistake of focusing on outputs rather than on outcomes or impacts. Outcomes, as the most immediate result of a policy, are easy to identify. Despite their similarities, outputs and outcomes are not identical. For instance, policymakers might be intent on lessening crime in a city. Local leaders often discuss the need for additional police officers as a means of achieving this goal. By adding more officers to the force (input), the output would be a higher number of officers patrolling the city. However, having more officers does not necessarily mean the outcome will be less crime or the impact will be a safer city. Perhaps the city has an unusually high rate of gang violence, or, because few job opportunities exist, most citizens live in poverty. If that is the case, the city will need to change their inputs to meet stated goals.