61 5.8 RATIONAL COMPREHENSIVE MODEL

RATIONAL COMPREHENSIVE MODEL

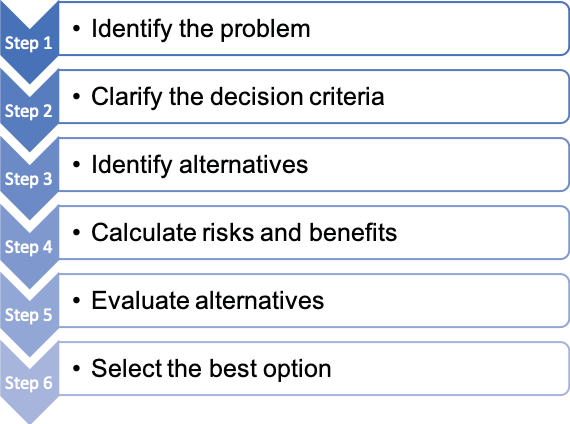

The American public would like to think that our representatives make rational policy decisions. The rational comprehensive model assumes that decisions are made after an individual rationally considers all options while estimating the trade-offs between costs and benefits. This model of decision making typically includes some combination of the following steps:

Figure 5.4: Rational Comprehensive Model Decision Making Steps

Source: Original Work Attribution: Kimberly Martin License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Proving that you have a problem worthy of government action requires evidence in the form of data collection, indicators, or focusing events. Sometimes identifying a problem is relatively easy. Take, for example, the high cost of student loan debt. The U.S. Department of Education reported that outstanding student loan debt topped $1.4 trillion in 2018, and the average student owed $29,200. These changing indicators are clear; loan debt is increasing. Furthermore, the effects of student loan debt can be seen in the economy. Young people are delaying homeownership, marriage, and family to pay off their loans (Hembree, 2018). In this case, the problem is clear; student loan debt is crippling individuals and the economy.

Next, we need to choose the variables that will help us evaluate options. In other words, clarify the decision criteria. What goals, values, or objectives will guide you as a decision maker? Determining what criteria is relevant and what is not usually depends on individual values and beliefs. For instance, say that you believe a college education is a necessity that has become far too expensive for the average person. Often, the only way a young person can afford that necessary degree is by taking out student loans. At this point, you have already identified values and beliefs that will guide your decision. First, college is necessary, and, second, it is too expensive for the average person. By extension, if someone wants to better themselves through attaining a college degree, their ability to pay for it should not be a barrier to that decision.

Step 3 in the rational model requires policymakers to identify alternatives. If your decision criteria necessitates access to a college degree, the alternatives that you choose will also encompass those values. For example, many policymakers and candidates for public office have proposed policies that would deliver a free college education. Others have proposed canceling student debt up to a certain amount or eliminating debt entirely.

If you value a college degree for everyone who chooses to pursue one, your alternatives will include a list of proposals similar to those mentioned above. If you believe that college is a choice and choosing not to go to college is a viable option or that students should not rely on government to pay off their debts, you will likely choose different alternatives. Perhaps your options will include holding colleges accountable for lowering the cost of tuition or educating borrowers about job prospects and starting pay for degree programs.

Once you have identified all alternatives, calculate their risks and benefits. Is one alternative likely to yield better results but is far too expensive to consider? Will specific options yield unintended consequences? As an example, if we choose to cancel student loan debt, how much will it cost taxpayers? Is this a sustainable option and will eliminating student debt help us reach the policy goal? Once the risks and benefits of each option have been established, move to step 5 where decision makers will measure each alternative against the other, comparing and evaluating their advantages and disadvantages. Finally, after each alternative is evaluated, the decision maker “chooses the alternative that maximizes the attainment of his or her goals, values, or objectives” (Stewart, Hedge & Lester, 2008). The result of this process should be a rational decision that is both efficient and achieves the desired goal.

Like most theoretical models, the rational comprehensive model is not immune to criticism. Many criticisms stem from the assumptions implied by the model. The first assumption is that decision makers can define a problem and identify all aspects of it; for example, think about how difficult it is to identify the root cause of crime. Is crime a direct result of environmental factors, such as poverty, unemployment, and low educational attainment? Is crime a result of societal and political factors, such as discriminatory policies or systemic racism? Alternatively, is crime caused by individuals with a tendency toward violence, alcohol and drug abuse, etc.? Unless decision makers can genuinely identify what causes a problem, they will be unable to identify and evaluate alternative solutions.

Second, the rational comprehensive model assumes that decision makers have complete knowledge of the alternatives for dealing with a problem and that it is “possible to predict the consequences with complete accuracy” (Stewart, Hedge, Lester, 2008). In truth, neither policymakers nor researchers will ever have complete information or be able to predict consequences with perfect accuracy. Decision makers can predict some outcomes, but policy making is inherently a “trial and error” process.

Herbert Simon (1947, 1956) famously wrote that rational behaviors are an unrealistic description of the decision-making process. Instead, Simon argued that people are more likely to “satisfice,” which is a term derived from the terms satisfy and suffice. In his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Economics, Simon explained that “decision makers can satisfice either by finding optimum solutions for a simplified world, or by finding satisfactory solutions for a more realistic world.” While he preferred to call this approach satisficing, what he described is what economists now refer to as bounded rationality. The central argument of bounded rationality is that no one makes completely rational decisions. We can easily observe this concept in real world situations. For instance, while policy makers may believe they are behaving rationally, they have actually developed short cuts or rules of thumb that help them make simplified and quicker decisions. The outcome of bounded rational decision making may not be optimal, but it is good enough.

Finally, even the most intelligent decision makers fall prey to their own self- interest. The greatest barrier to rational decision making is often human nature. Decision makers, especially in politics, often inevitably make decisions based on their own goals rather than on serving the greater good. Moreover, the rational decision-making process assumes there is only one decision maker, which is rarely the case. Multiple groups and many people often develop policies. Imagine considering the preferences of not one person but a group when deciding which alternative to choose.