72 6.1 – WHO IMPLEMENTS POLICY?

WHO IMPLEMENTS POLICY?

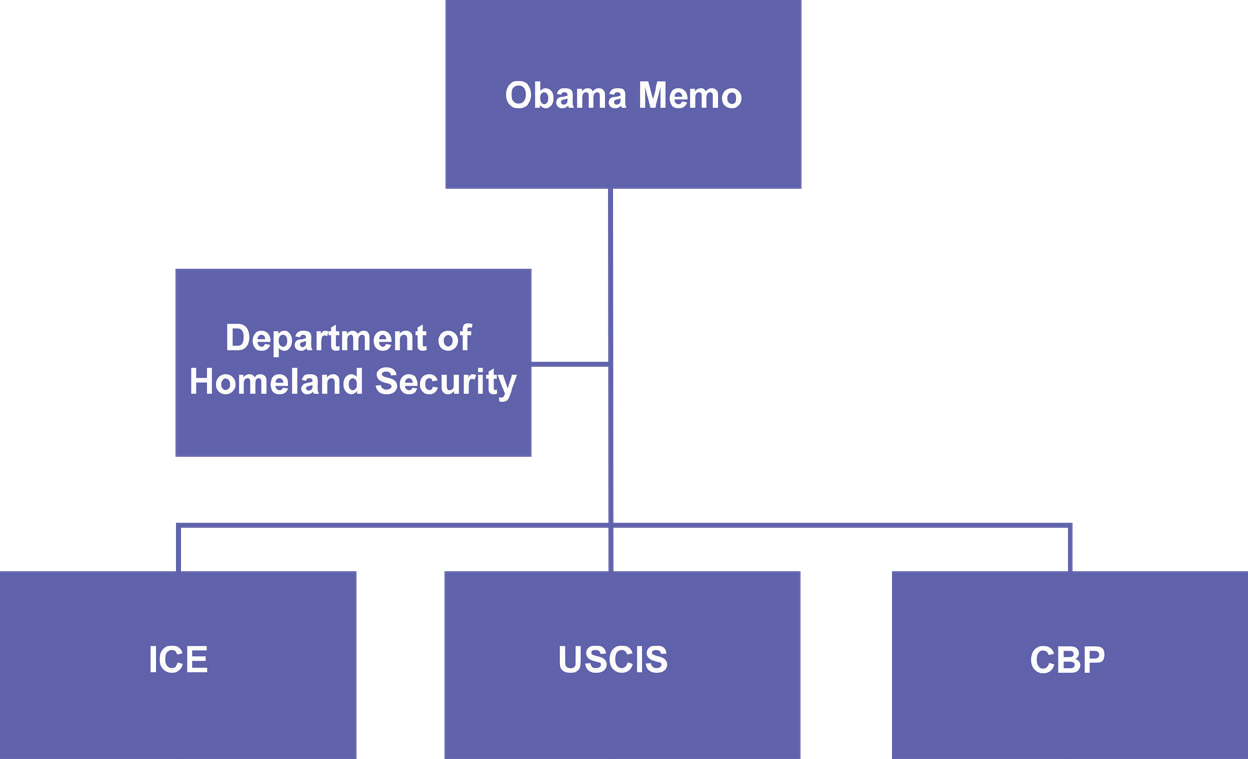

According to Weimer and Vining (2017), the implementation process involves managers, doers, and fixers. Managers assemble the policy machine and direct doers on how to implement the policy. They include senior supervisors and mid-level bureaucrats. Managers are directed by agency officials—like cabinet officials—to carry out policy and oversee the work of doers in the implementation process. It is important that managers favor the policy, or they may not be willing to expend personal or organizational resources to effectively implement the policy. Furthermore, when policy is ambiguous, managers who do not favor the policy may apply an interpretation that does not align with the intent of the policy maker. Assuming the manager favors the policy and is capable of working with other managers when required, that manager must have the capacity to incentivize the doers. This capacity relies on various resources, most notably “authority, political support, and treasure” (Weimer and Vining, 2017). Managers must be able to assemble a policy machine with enough structure that the policy can be successfully implemented but remain flexible enough to adapt to change. Managers are also responsible for coordinating with other agencies if the policy requires horizontal coordination, whereby the policy relies on a number of agencies across one level of government to successfully execute the program. For example, President Obama issued the executive branch memorandum Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) on June 15, 2012. DACA required the coordination of the Department of Homeland Security, which oversaw the implementation; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS); and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). For its successful implementation, DACA required not only buy-in from subordinate bureaucrats but also the successful coordination of agency leaders.

Figure 6.1: Horizontal Coordination Source: Original Work Attribution: Keith Lee Source: CC BY-SA 4.0 6.2.1.

Doers

Doers, on the other hand, often deal directly with clients at the street level and are called street-level bureaucrats. Street-level bureaucrats are directly responsible for service delivery and are those of whom most people think when they think of the bureaucracy. One major complaint many have with bureaucracy is unnecessary and burdensome red tape. The red tape is often seen at the street- level. Teachers and police officers commonly exemplify street-level bureaucrats; other examples include case workers, public defenders, and health department employees. Generally speaking, anyone responsible for delivering public services directly to the public is a street-level bureaucrat. According to Lipsky (1980), street-level bureaucrats are at the heart of political debate involving service delivery for two primary reasons: (1) “debates over proper scope and focus of governmental services are essentially debates over the scope and function of these public employees,” and (2) “street-level bureaucrats have considerable impact over people’s lives.” Furthermore, they “determine eligibility” and “oversee the treatment citizens receive.”

In order to effectively implement policy, doers rely on resources provided by managers, including staff, time, and money. These resources can be used to incentivize doers who do not favor a specific policy and so do not want to comply. Much like managers, doers can hinder policy implementation in a variety of ways, most notably through tokenism, massive resistance, and social entropy (Bardach, 1977). Tokenism occurs when implementation appears to be going as planned publicly, while behind the scenes doers are only pushing a small, or “token,” contribution. An example of this type of situation would be a policy requiring agencies to hire more women in certain departments to ensure even representation in the agency. However, rather than completing the requirement as defined, the agency may simply promote a woman or a number of women to higher ranks to create the appearance of equality in the agency. Tokenism can also be seen when doers delay compliance or provide inferior service. Tokenism in practice allows opponents of the policy an opening to point out the poor implementation, which could lead to policy overhaul or termination. Doers engage in massive resistance when they withhold specific program elements until administrators sanction their behavior. However, if agency heads, fixers, and/or managers are unable to quell the resistance fast enough, the policy could fail, particularly if there is political opposition, competing policy alternatives, or lack of constituent support. In essence, tokenism can be resolved with carrots, or incentives, whereas massive resistance relies on sticks, or sanctions.

According to Bardach (1977), social entropy manifests itself in three distinct problems: incompetence, variability, and coordination. Incompetence involves the inability of perfectly compliant doers to successfully implement policy, even when policy directives are clear. Organizational turnover is a primary contributor to incompetent bureaucrats, as they are unable to develop the skills necessary for successful policy implementation. This concept rings true particularly among street-level bureaucrats who are new to their positions and who may not be familiar with organizational norms or policies. Furthermore, bureaucrats at all levels may lack an understanding of the vast number of policies the organization is responsible for carrying out. All of these factors cripple well-timed policy execution.

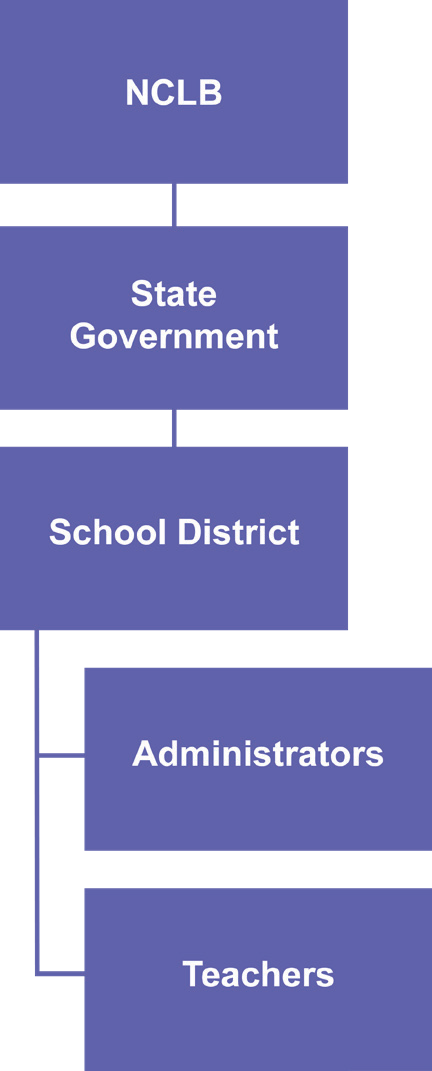

Variability, on the other hand, stems from a systematic approach to policy- making that is not equipped to handle various societal issues that affect parties responsible for executing the policy. This is particularly true when vertical coordination is required. Vertical coordination, unlike horizontal coordination, does not rely on agencies or other units across a single level to work together for policy implementation. Rather, the policy calls for top-down coordination whereby a senior official works with subordinate organizations, individuals, or agencies to implement a policy. Furthermore, the top-down approach can consist of more than two levels of government. For example, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) relied on vertical coordination at more than two levels. The act required states to develop standards that could be assessed and that would demonstrate improved education outcomes for individual students in order to receive federal funding. States were then responsible for holding individual school districts accountable for performing assessments and demonstrating Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) by meeting “high standards.” High standards, in this case, is an ambiguous term that was left up to the states to define. Critics of the policy argued that the law reduced teacher freedom in the classroom and required educators to teach to the test. Furthermore, critics argued that states and school districts lacked adequate control to alter their curriculum and standards based on community needs. At its core, NCLB relied on doers—for example, school board officials and teachers—to pursue high standards and quality assessment. The criticism from parents, teachers, and officials required the policy machine to be overhauled to better deliver a policy that would in turn provide better educational outcomes. President Obama granted exemptions to 32 states in 2012, and the law was replaced in 2015 by the Every Student Succeeds Act, which reduced the federal government’s role by allowing more flexibility within states.

Figure 6.2: Vertical Coordination Source: Original Work Attribution: Keith Lee License: CC BY-SA 4.0  Finally, coordination problems arise when individuals responsible for carrying out the policy within different organizations interpret the policy differently or vary in their level of support for the policy. The term generally refers to horizontal coordination, mentioned above, regarding the role of managers to work well with others, but could also refer to vertical coordination. For the sake of simplicity, we will only consider horizontal coordination which requires parallel cooperation, since vertical coordination relies on a manager-subordinate relationship that can force cooperation.

Finally, coordination problems arise when individuals responsible for carrying out the policy within different organizations interpret the policy differently or vary in their level of support for the policy. The term generally refers to horizontal coordination, mentioned above, regarding the role of managers to work well with others, but could also refer to vertical coordination. For the sake of simplicity, we will only consider horizontal coordination which requires parallel cooperation, since vertical coordination relies on a manager-subordinate relationship that can force cooperation.

Conversely, horizontal coordination relies on mutually accepted goals that are deemed efficient and cost effective. The process requires agency heads, managers, and doers to agree on an outcome favorable to all parties. Furthermore, doers are those most burdened by coordination requirements. Policy makers may provide resources at different levels to coordinating agencies, which could result in one or more agencies lacking the necessary resources to perform their duties effectively. In sum, poor coordination among agencies, particularly among doers, may result in tokenism or massive resistance. In these cases, fixers may be asked to step in to rectify coordination problems to ensure policy success.

Fixers

As noted by Rhodes (2016), the shift in public administration to the New Public Governance (NPG) model calls on public servants to become agents who manage “complex, non-routing issues, policies, and relationships.” Fixers exemplify this call as they are the individuals called up to work within the policy arena to alleviate tension between managers and doers or to alleviate tensions that develop when coordination problems arise. Fixers can be directly involved with policy creation, as can, for example, a legislative staff member, or on the ground level supporting a policy and ensuring its successful implementation, as can a manager or doer who favors the policy and needs agency coordination for policy implementation. The former will likely work between managers and doers to determine what resources are needed for successful implementation, whereas the latter will serve as the eyes and ears for managers to assist in getting non-compliant or reluctant doers in line. Fixers may also be required to work with policy makers, at the recommendation of managers and doers, to add a new policy dimension for successful implementation. Fixers, to be successful, must be capable of anticipating problems before they develop. As we will discuss in the next section, fixers are better suited for developing contingency plans based on alternative scenario planning. Additionally, fixers must be coalition builders, particularly when working with multiple agencies. Majority coalition building requires the fixer to find common ground among the most receptive agencies in order to get the least receptive agencies on board. Lastly, fixers need to be familiar with the various factors that hinder policy implementation and work with policy makers in addressing those factors.