13.1 Motivation Theories and the Workplace

Organizational behavior studies how individuals, groups, and structures impact human behavior within organizations. It is an interdisciplinary field that includes sociology, psychology, communication, and management. Organizational behavior complements organizational theory, which focuses on organizational and intra-organizational topics, and complements human-resource studies, which focuses on everyday business practices.

Why should we care about job satisfaction? Or, more specifically, why should an employer care about job satisfaction? Measures of job satisfaction are somewhat correlated with job performance; in particular, they appear to relate to organizational citizenship or discretionary behaviors on the part of an employee that further the organization’s goals (Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012). Job satisfaction is related to general life satisfaction. However, there has been limited research on how the two influence each other or whether personality and cultural factors affect job and general life satisfaction. This lesson will discuss how organizational behavior, the workplace, and culture impact our motivation to succeed.

Learning Objectives

- Define diversity and inclusion and their role in the workplace.

- Describe the steps needed to have a diverse and inclusive workforce.

- Outline the differences between hygiene factors and motivators.

Motivation

The earliest studies of motivation involved an examination of individual needs. Specifically, early researchers thought that employees try hard and demonstrate goal-driven behavior to satisfy needs. For example, an employee always walking around the office talking to people may need companionship, and his behavior may be a way of satisfying this need. At the time, researchers developed theories to understand what people need and grouped those theories under the following categories:

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

- ERG Theory

- Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

- McClelland’s Acquired Needs Theory

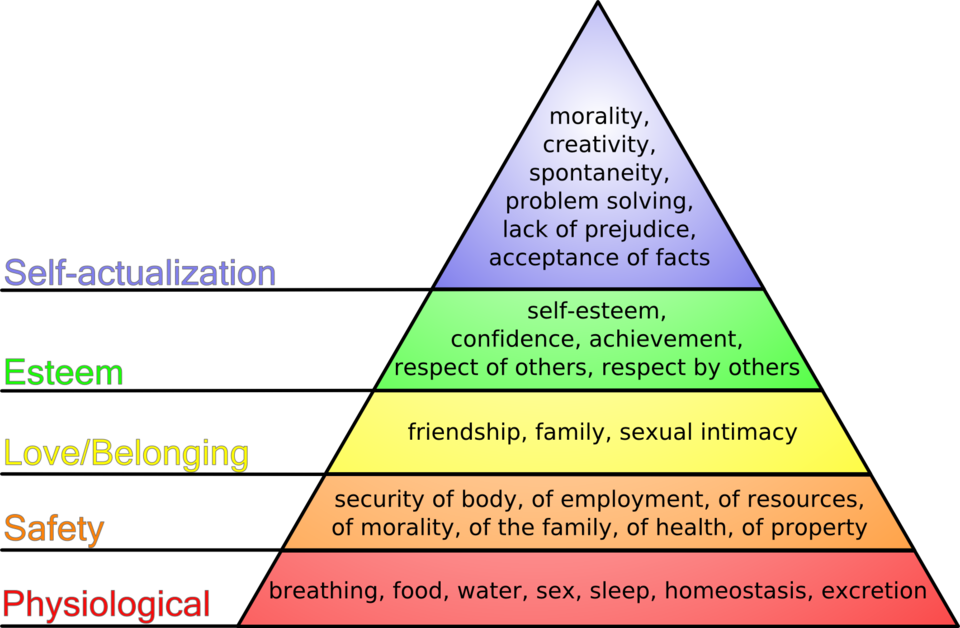

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (open YouTube video in new tab)

Abraham Maslow is among the most prominent psychologists of the twentieth century. His hierarchy of needs is an image familiar to most business students and managers. The theory is based on a simple premise: human beings have hierarchically ranked needs (Maslow, 1943; Maslow, 1954). Some needs are basic to all human beings, and in their absence, nothing else matters. As we satisfy these basic needs, we seek higher-order needs. In other words, once a lower-level need is satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator.

The most basic of Maslow’s needs are physiological needs — those that refer to the need for food, water, shelter, etc. These needs are basic because when they are lacking, the search for them may overpower all other urges. Imagine being very hungry. At that point, all your behavior may be directed at finding food. Once you eat, though, the search for food ceases, and the promise of food no longer serves as a motivator. Once physiological needs are satisfied, people tend to become concerned about safety needs. Are they free from the threat of danger, pain, or an uncertain future? On the next level up, social needs refer to the need to bond with other human beings, to be loved, and to form lasting attachments with others. In fact, attachments, or lack thereof, are associated with our health and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). The satisfaction of social needs makes esteem needs more salient. Esteem refers to the desire to be respected by one’s peers, one’s importance, and to be appreciated. Finally, at the highest level of the hierarchy, the need for self-actualization refers to “becoming all you are capable of becoming.” This need manifests itself in the desire to acquire new skills, take on new challenges, and behave in a way that will lead to attaining one’s life goals.

Maslow was a clinical psychologist whose theory was not originally designed for work settings. It was based on his observations of individuals in clinical settings; some of the individual components of the theory found little empirical support. One criticism relates to the order in which the needs are ranked. It is possible to imagine that individuals who go hungry and are in fear for their lives might retain strong bonds with others, suggesting a different order of needs. Moreover, researchers failed to support the arguments that once a need is satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator and that only one need is dominant at a given time (Neher, 1991; Rauschenberger et al., 1980).

Despite lacking strong research support, Maslow’s theory has obvious applications in business settings. Understanding what people need gives us clues to understanding them. The hierarchy is a systematic way of thinking about the different needs employees may have at any given point and explains different reactions to similar treatment. An employee who is trying to satisfy esteem needs may feel gratified when her supervisor praises an accomplishment. However, another employee trying to satisfy social needs may resent being praised by upper management in front of peers if the praise sets the individual apart from the rest of the group.

How can an organization satisfy its employees’ various needs? In the long run, physiological needs may be satisfied by the person’s paycheck, it is important to remember that pay may also satisfy other needs, such as safety and esteem. Providing generous benefits that include health insurance and company-sponsored retirement plans, and offering a measure of job security, will help satisfy safety needs. Social needs may be satisfied by having a friendly environment and providing a workplace conducive to collaboration and communication with others. Company picnics and other social get-togethers may also be helpful if most employees are motivated primarily by social needs (but may cause resentment if they are not and if they have to sacrifice a Sunday afternoon for a company picnic). Providing promotion opportunities at work, recognizing a person’s accomplishments verbally or through more formal reward systems, and conferring job titles that communicate to the employee that one has achieved high status within the organization are among the ways of satisfying esteem needs. Finally, self-actualization needs may be satisfied by the provision of development and growth opportunities on or off the job, as well as by interesting and challenging work. By attempting to satisfy each employee’s needs, organizations may ensure a highly motivated workforce.

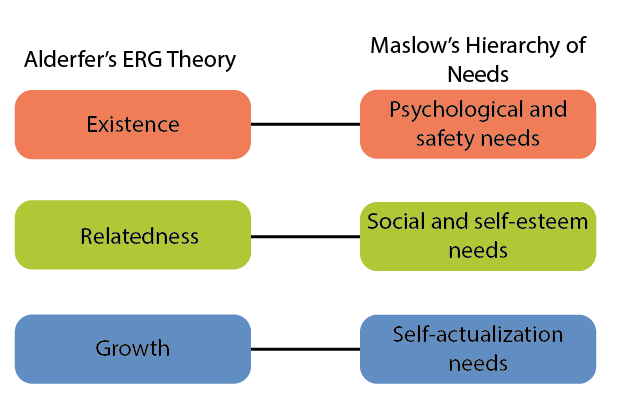

ERG Theory

ERG theory, developed by Clayton Alderfer, is a modification of Maslow’s Hierarchy (Alderfer, 1969). Instead of the five needs that are hierarchically organized, Alderfer proposed that basic human needs may be grouped under three categories, namely, existence, relatedness, and growth. Existence corresponds to Maslow’s physiological and safety needs, relatedness corresponds to social needs, and growth refers to Maslow’s self-actualization.

ERG theory’s main contribution to the literature is its relaxation of Maslow’s assumption. For example, ERG theory does not rank needs in any particular order and explicitly recognizes that more than one need may operate at a given time. Moreover, the theory has a “frustration-regression” hypothesis suggesting that individuals who are frustrated in their attempts to satisfy one need may regress to another. For example, someone who is frustrated by the growth opportunities in his job and progress toward career goals may regress to the relatedness need and start spending more time socializing with coworkers. This theory implies that we need to recognize the multiple needs that may be driving individuals at a given point to understand their behavior and properly motivate them.

Two-Factor Theory

Frederick Herzberg approached the question of motivation differently by asking workers to share their motivation. By asking individuals what satisfies them on the job and what dissatisfies them, Herzberg came to the conclusion that aspects of the work environment that satisfy employees are very different from aspects that dissatisfy them (Herzberg et al., 1959; Herzberg, 1965). Herzberg labeled factors causing dissatisfaction among workers as “hygiene” factors because they were part of the context in which the job was performed, as opposed to the job itself. Hygiene factors included company policies, supervision, working conditions, salary, safety, and security on the job. To illustrate, imagine that you are working in an unpleasant work environment. Your office is too hot in the summer and too cold in the winter. You are being harassed and mistreated. You would certainly be miserable in such a work environment. However, if these problems were solved (your office temperature is just right, and you are not harassed at all), would you be motivated? Most likely, you would take the situation for granted. In fact, many factors in our work environment are things we miss when they are absent but take for granted if they are present.

In contrast, motivators are factors that are intrinsic to the job, such as achievement, recognition, interesting work, increased responsibilities, advancement, and growth opportunities. According to Herzberg’s motivators are the conditions that truly encourage employees to try harder.

| Hygiene Factor | Motivators |

|---|---|

| Company policy | Achievement |

| Supervision and relationships | Recognition |

| Working conditions | Increased responsibility |

| Salary | Advancement |

| Security | Growth |

Herzberg’s research is far from being universally accepted (Cummings & Elsalmi, 1968; House & Wigdor, 1967). One criticism relates to the primary research methodology employed when arriving at hygiene versus motivators. When people are asked why they are satisfied, they may attribute the causes of satisfaction to themselves, whereas when explaining what dissatisfies them, they may blame the situation. Classifying the factors as hygiene or motivator is not that simple either. For example, the theory views pay as a hygiene factor. However, pay may have symbolic value by showing employees that they are being recognized for their contributions and communicating that they are advancing within the company. Similarly, the quality of supervision or the types of relationships employees form with their supervisors may determine whether they are assigned interesting work, are recognized for their potential, and take on more responsibilities.

Despite its limitations, the theory can be a valuable aid to managers because it points out that improving the environment in which the job is performed goes only so far in motivating employees. Undoubtedly, contextual factors matter because their absence causes dissatisfaction. However, solely focusing on hygiene factors will not be enough, and managers should also enrich jobs by giving employees opportunities for challenging work, greater responsibilities, advancement opportunities, and a job in which their subordinates can feel successful.

Among the need-based approaches to motivation, David McClelland’s Acquired Needs theory is the one that has received the greatest amount of support. According to this theory, individuals acquire three types of needs due to their life experiences. These needs are the need for achievement, the need for affiliation, and the need for power. All individuals possess a combination of these needs, and the dominant needs are thought to drive employee behavior.

McClelland used a unique method called the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to assess the dominant need (Spangler, 1992). This method entails presenting research subjects with an ambiguous picture and asking them to write a story based on it. Take a look at the following picture. Who is this person? What are they doing? Why are they doing it? Trained experts would then analyze the story you tell about the woman in the picture. The idea is that the stories the photo evokes would reflect how the mind works and what motivates the person.

The type of story you tell by looking at this picture may give away the dominant need that motivates you.

If the story you come up with contains themes of success, meeting deadlines, or coming up with brilliant ideas, you may be high in the need for achievement. Those with a high need for achievement have a strong need to succeed. As children, they may be praised for their hard work, which forms the foundation of their persistence (Mueller & Dweck, 1998). As adults, they are preoccupied with doing things better than they did in the past. These individuals are constantly striving to improve their performance. They relentlessly focus on goals, particularly stretch goals that are challenging in nature (Campbell, 1982). They are particularly suited to positions such as sales, where there are explicit goals, feedback is immediately available, and their effort often leads to success. In fact, they are more attracted to organizations that are merit-based and reward performance rather than seniority. They also do particularly well as entrepreneurs, scientists, and engineers (Harrell & Stahl, 1981; Trevis & Certo, 2005; Turban & Keon, 1993).

Are individuals who are high in the need for achievement effective managers? Because of their success in lower-level jobs where their individual contributions matter the most, those with a high need for achievement are often promoted to higher-level positions (McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982). However, a high need for achievement has significant disadvantages in management positions. Management involves getting work done by motivating others. When a salesperson is promoted to sales manager, the job description changes from actively selling to recruiting, motivating, and training salespeople. Those who are high in the need for achievement may view managerial activities such as coaching, communicating, and meeting with subordinates as a waste of time and may neglect these aspects of their jobs. Moreover, those high in need for achievement enjoy doing things themselves and may find it difficult to delegate any meaningful authority to their subordinates. These individuals often micromanage, expecting others to approach tasks in a particular way, and may become overbearing bosses by expecting everyone to display high levels of dedication (McClelland & Burnham, 1976).

If the story you created in relation to the picture you are analyzing contains elements of making plans to be with friends or family, you may have a high need for affiliation. Individuals with a high need for affiliation want to be liked and accepted by others. When given a choice, they prefer interacting with others and being with friends (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). Their emphasis on harmonious interpersonal relationships may be advantageous in jobs and occupations requiring frequent interpersonal interaction, such as social workers or teachers. In managerial positions, a high need for affiliation may again serve as a disadvantage because these individuals tend to be overly concerned about how others perceive them. They may find it difficult to perform some aspects of a manager’s job such as giving employees critical feedback or disciplining poor performers. Thus, the work environment may be characterized by mediocrity and may even lead to high performers leaving the team.

Finally, if your story contains elements of getting work done by influencing other people or desiring to impact the organization, you may have a high need for power. Those with a high need for power want to influence others and control their environment. A need for power may be a destructive element in relationships with colleagues if it takes the form of seeking and using power for one’s own good and prestige. However, when it manifests itself in more altruistic forms, such as changing how things are done so that the work environment is more positive or negotiating more resources for one’s department, it tends to lead to positive outcomes. In fact, the need for power is viewed as an important trait for effectiveness in managerial and leadership positions (McClelland & Burnham, 1976; Spangler & House, 1991; Spreier, 2006).

McClelland’s Acquired Needs theory has important implications for the motivation of employees. Managers need to understand the dominant needs of their employees to be able to motivate them. While people with a high need for achievement may respond to goals, those with a high need for power may attempt to gain influence over those they work with, and individuals high in their need for affiliation may be motivated to gain the approval of their peers and supervisors. Finally, those who have a high drive for success may experience difficulties in managerial positions, and making them aware of common pitfalls may increase their effectiveness.

Key Takeaways

Need-based theories describe motivated behavior as individual efforts to meet their needs. According to this perspective, the manager’s job is to identify what people need and make the work environment a means of satisfying these needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy categorizes five basic human needs into: physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization. These needs are hierarchically ranked, and as a lower-level need is satisfied, it no longer serves as a motivator.

ERG theory is a modification of Maslow’s hierarchy in which the five needs are collapsed into three categories (existence, relatedness, and growth). The theory recognizes that when employees are frustrated while attempting to satisfy higher-level needs, they may regress.

The two-factor theory differentiates between factors that make people dissatisfied on the job (hygiene factors) and factors that truly motivate employees (motivators).

Finally, acquired-needs theory argues that individuals possess stable and dominant motives to achieve, acquire power, or affiliate with others. The type of need that is dominant will drive behavior.

Each of these theories explains the characteristics of a work environment that motivates employees. These theories paved the way for process-based theories that explain employees’ motivations to decide how to behave.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- pexels-rethaferguson-3810753 (1) © RF._.studio is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 960px-Maslow’s_hierarchy_of_needs © J. Finkelstein is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- ERGandMaslow1 © Lumen Learning is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Barack_Obama_looking_JFK_portrait (1) © Pete Souza is licensed under a Public Domain license