10.2 Universal Disorders

There’s no shame in taking care of your mental health | Sangu Delle (open YouTube video in new tab)

It is difficult to get a consensus on the definition of a disorder and whether it exists outside of a cultural context. Universal disorder refers to the incidence of a particular set of symptoms occurring across various cultures and circumstances. The identification of a mental health condition as “universal” tends to describe that condition as occurring in human nature across various contexts. It focuses on the genetic and biological factors contributing to the condition, in addition to cultural/contextual factors. While the debate about culture-specific versus universal conditions continues in regard to clinical diagnosis, most experts agree that viewing illness through the lens of culture is imperative when addressing symptoms, societal stigma, and treatment options.

In this module, we will explore the symptoms and diagnostic criteria of four mental health categories seen across the globe.

The four mental health categories observed globally are:

- Major Depressive Disorder

- Anxiety Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Psychosis

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

Everyone experiences brief periods of sadness, irritability, or euphoria. This is different from having a mood disorder, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder, which are characterized by a constellation of symptoms that cause people significant distress or impair their everyday functioning.

A major depressive episode (MDE) refers to symptoms that co-occur for at least two weeks and cause significant distress or impairment in functioning, such as interfering with work, school, or relationships. Core symptoms include feeling down or depressed, or experiencing anhedonia—loss of interest or pleasure in things that one typically enjoys. According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (APA, 2013), the criteria for an MDE require the presence of five or more of the following nine symptoms, including one or both of the first two symptoms, for most of the day, nearly every day:

- Depressed mood

- Diminished interest or pleasure in almost all activities

- Significant weight loss or gain, or an increase or decrease in appetite

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feeling worthless or excessive, or inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to concentrate or indecisiveness

- Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt

These symptoms cannot be caused by the physiological effects of substance abuse or a general medical condition, such as hypothyroidism, for example.

Major Depressive Disorder-Cross-Cultural Considerations

In a nationally representative sample, the lifetime prevalence rate for MDD is 16.6% (Kessler et al., 2005). This means that nearly one in five Americans will meet the criteria for MDD during their lifetime.

Although the onset of MDD can occur at any time throughout the lifespan, the average age of onset is mid-20s, with the age of onset decreasing with people born more recently (APA, 2000). Prevalence of MDD among older adults is much lower than it is for younger cohorts (Kessler, Birnbaum, Bromet, Hwang, Sampson, & Shahly, 2010). The duration of MDEs varies widely. MDD tends to be a recurrent disorder, with about 40%–50% of those who experience one MDE experiencing a second MDE (Monroe & Harkness, 2011). An earlier age of onset predicts a worse course.

Women experience two to three times higher rates of MDD than do men (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009). This gender difference emerges during puberty (Conley & Rudolph, 2009). Before puberty, boys exhibit similar or higher prevalence rates of MDD than do girls (Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). MDD is inversely correlated with socioeconomic status (SES), a person’s economic and social position based on income, education, and occupation. Higher prevalence rates of MDD are associated with lower SES (Lorant et al., 2003), particularly for adults over 65 years old (Kessler et al., 2010).

Independent of SES, results from a nationally representative sample found that European Americans had a higher prevalence rate of MDD than did African Americans and Hispanic Americans, whose rates were similar (Breslau et al., 2006). The course of MDD for African Americans is often more severe and less often treated than it is for European Americans, however (Williams et al., 2007). Native Americans have a higher prevalence rate than do European Americans, African Americans, or Hispanic Americans (Hasin et al., 2005). Depression is not limited to industrialized or Western cultures; it is found in all countries that have been examined, although the symptom presentation, as well as prevalence rates, vary across cultures (Chentsova Dutton & Tsai, 2009).

Suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one’s own death. While not everyone who is clinically depressed has suicidal ideation, it is important to recognize that depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, and substance abuse, including alcoholism and the use of benzodiazepines, are risk factors. Those who have previously attempted suicide are at a higher risk of future attempts. There are a number of treatments that may reduce the risk of suicide for individuals struggling with mental illness.

Black youth suicide rates and attempts have increased alarmingly during the last two decades (SAMHSA 2025). Factors influencing depressive episodes among Black youth include: race-based discrimination, poverty, racially based anticipatory stress due to police violence, history with child protective services, or with family incarceration. Suicide risk is exacerbated by the absence of sufficient healthcare services — either due to cost, lack of health insurance, healthcare facility location, or distrust of healthcare practitioners. However, promising research by Hollingsworth & Polanco-Roman (2022) suggests that African American young adults who strongly explore and commit to their ethnic identity might be less affected by feelings of defeat and being trapped, which can help protect them from thoughts of suicide.

The National 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline[New Tab] is a resource for anyone facing mental health struggles, emotional distress, alcohol or drug use concerns, or just needing someone to talk to. Resources are also commonly in place at most colleges. Consider searching your school website and/or talking with a trusted faculty/staff member to learn more about resources available to students.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is a natural part of life and, at normal levels, helps us to function at our best. However, for people with anxiety disorders, anxiety is overwhelming and hard to control.

Anxiety disorders develop out of a blend of biological and psychological factors that, when combined with stress, may lead to the development of ailments. Primary anxiety-related diagnoses include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), post-traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Anxiety can be defined as a negative mood state that is accompanied by bodily symptoms such as increased heart rate, muscle tension, a sense of unease, and apprehension about the future (APA, 2013; Barlow, 2002).

While many individuals experience some levels of worry throughout the day, individuals with anxiety disorders experience symptoms of greater intensity and for longer periods of time than the average person. Additionally, they are often unable to control their worry, tension, and/or predictive dread through various coping strategies, which directly interfere with their ability to engage in daily social and occupational tasks.

Characteristic symptoms of various anxiety conditions include:

- Negative mood state characterized by unease, worry, tension, and/or dread.

- Frequent doubts regarding self-worth and/or ability to handle problems.

- Future-based, “predicative” fears for events.

- Difficulty with cognitive rumination, racing thoughts, and inability to calm the mind.

- Physiological cues (racing heart, sweat, bodily tension, etc.), often accompanying cognitive symptoms, result in changing sleep/eating patterns.

Anxiety disorders often occur along with other mental disorders, in particular depression, which may occur in as many as 60% of people with anxiety disorders. The fact that there is considerable overlap between symptoms of anxiety and depression, and that the same environmental triggers can provoke symptoms in either condition, may help to explain this high rate of comorbidity, the simultaneous presence of two chronic diseases or conditions.

Anxiety Disorders: Cross-Cultural Considerations

About 12% of people are affected by an anxiety disorder in a given year, and between 5% and 30% are affected at some point in their lives. They occur about twice as often in females as males and generally begin before the age of 25. The most common are specific phobia, which affects nearly 12%, and social anxiety disorder, which affects 10% at some point in their life. Rates of anxiety appear to be higher in the United States and Europe than in other parts of the world.

Eating Disorders

While nearly two out of three US adults struggle with issues related to being overweight, a smaller, but significant, portion of the population has eating disorders that typically result in being normal weight or underweight.

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by the maintenance of a body weight well below average through starvation and/or excessive exercise. Individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa often have a distorted body image, referenced in literature as a type of body dysmorphia, persistent and intrusive preoccupations with an imagined defect in one’s appearance. Individuals who suffer from anorexia nervosa view themselves as overweight even though they are not. Anorexia nervosa is associated with a number of significant negative health outcomes: bone loss, heart failure, kidney failure, amenorrhea (cessation of the menstrual period), reduced function of the gonads, and in extreme cases, death. Furthermore, there is an increased risk for a number of psychological problems, which include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance abuse (Mayo Clinic, 2012a). The lifetime prevalence rates of anorexia nervosa are up to 4% among females and 0.3% among males. Regarding bulimia nervosa, up to 3% of females and more than 1% of males suffer from this disorder during their lifetime. While epidemiological studies in the past mainly focused on young females from Western countries, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are reported worldwide among males and females of all ages (van Eeden et al. 2021).

People suffering from bulimia nervosa engage in binge eating behavior that is followed by an attempt to compensate for the large amount of food consumed. Purging the food by inducing vomiting or through the use of laxatives is a common compensatory behavior, a behavior meant to compensate or “undo” eating and utilized to relieve guilt associated with eating and consuming more calories than intended. Some affected individuals engage in excessive amounts of exercise to compensate for their binges. Bulimia is associated with many adverse health consequences that can include kidney failure, heart failure, and tooth decay. In addition, these individuals often suffer from anxiety and depression, and they are at an increased risk for substance abuse (Mayo Clinic, 2012b). The lifetime prevalence rate for bulimia nervosa is estimated at around 1% for women and less than 0.5% for men (Smink et al., 2012).

The following video further explains eating disorders.

Eating Disorders – Akron Children’s Hospital (open YouTube video in new tab)

Eating Disorders: Cross-Cultural Considerations

While both anorexia and bulimia nervosa occur in men and women of many different cultures, Caucasian females from Western societies tend to be the most at-risk population. Recent research indicates that females between the ages of 15 and 19 are most at risk, and it has long been suspected that these eating disorders are culturally-bound phenomena that are related to messages of a thin ideal often portrayed in popular media and the fashion world (Smink et al., 2012). While social factors play an important role in the development of eating disorders, there is also evidence that genetic factors may predispose people to these disorders (Collier & Treasure, 2004). Sociocultural factors that emphasize thinness as a beauty ideal and a genetic predisposition contribute to the development of eating disorders in many young females, especially in Westernized cultures.

Psychosis

Most of you have probably had the experience of walking down the street in a city and seeing a person you thought was acting oddly. They may have been dressed in an unusual way, perhaps disheveled or wearing an unusual collection of clothes, makeup, or jewelry that did not seem to fit any particular group or subculture. They may have been talking to themselves or yelling at someone you could not see. If you tried to speak to them, they may have been difficult to follow or understand, or they may have acted paranoid or started telling a bizarre story about the people who were plotting against them. If so, chances are that you have encountered an individual with schizophrenia or another type of psychotic disorder.

Schizophrenia is a devastating psychological disorder that is characterized by major disturbances in thought, perception, emotion, and behavior. About 1% of the population experiences schizophrenia in their lifetime, and usually the disorder is first diagnosed during early adulthood (early to mid-20s). Schizophrenia and the other psychotic disorders are some of the most impairing forms of psychopathology, frequently associated with a profound negative effect on the individual’s educational, occupational, and social function. Sadly, these disorders often manifest right at the time of the transition from adolescence to adulthood, just as young people should be evolving into independent young adults.

The spectrum of psychotic disorders includes schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, as well as psychosis associated with substance use or medical conditions. Even when they receive the best treatments available, many with schizophrenia will continue to experience serious social and occupational impairment throughout their lives.

The main symptoms of schizophrenia include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking, disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms (APA, 2013).

A hallucination is a visual, verbal, or physical illusion that a person sees, hears, or feels and mistakes for reality. Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices) occur in roughly two-thirds of patients with schizophrenia and are by far the most common form of hallucination (Andreasen, 1987). The voices may be familiar or unfamiliar, they may have a conversation or argue, or the voices may provide a running commentary on the person’s behavior (Tsuang et al., 1999).

Delusions are false beliefs that are often fixed, hard to change even when the person is presented with conflicting information, and are often culturally influenced in their content (e.g., delusions involving Jesus in Judeo-Christian cultures, delusions involving Allah in Muslim cultures). They can be terrifying for the person, who may remain convinced that they are true even when loved ones and friends present them with clear information that they cannot be true. There are many different types of themes for delusions.

Talking with someone with schizophrenia is sometimes difficult, as their speech may be incoherent and difficult to follow, either because their answers do not clearly flow from your questions, or because one sentence does not logically follow from another. This is referred to as disorganized speech, and it can be present even when the person is writing. Disorganized behavior can include odd dress, odd makeup (e.g., lipstick outlining the lips by 1 inch), or unusual rituals (e.g., repetitive hand gestures).

Some of the most debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia are difficult for others to see. These include what people refer to as negative symptoms or the absence of certain behaviors or abilities we typically expect most people to demonstrate. For example, anhedonia or amotivation reflects a lack of apparent interest in or drive to engage in social or recreational activities. These symptoms can manifest as a great amount of time spent in physical immobility. Importantly, anhedonia and amotivation do not seem to reflect a lack of enjoyment in pleasurable activities or events (Cohen & Minor, 2010; Kring & Moran, 2008; Llerena et al., 2012) but rather a reduced drive or ability to take the steps necessary to obtain the potentially positive outcomes (Barch & Dowd, 2010). Flat affect and reduced speech (alogia) reflect a lack of showing emotions through facial expressions, gestures, and speech intonation, as well as a reduced amount of speech and increased pause frequency and duration.

Schizophrenia: Cross-Cultural Considerations

It is clear that there are important genetic contributions to the likelihood that someone will develop schizophrenia, with consistent evidence from family, twin, and adoption studies. (Sullivan et al., 2003). However, there is no “schizophrenia gene,” and it is likely that the genetic risk for schizophrenia reflects the summation of many different genes that each contribute something to the likelihood of developing psychosis (Gottesman & Shields, 1967; Owen et al., 2010). Further, schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous disorder, which means that two different people with “schizophrenia” may each have very different symptoms (e.g., one has hallucinations and delusions, the other has disorganized speech and negative symptoms).

About 0.3% to 0.7% of people are affected by schizophrenia during their lifetimes. In 2013, there were an estimated 23.6 million cases globally. Males are more often affected and, on average, experience more severe symptoms. About 20% of people eventually do well, and a few recover completely, while about 50% have lifelong impairment. Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty, and homelessness, are common. The average life expectancy of people with the disorder is ten to twenty-five years less than that of the general population. This is the result of increased physical health problems and a higher suicide rate (about 5%). In 2015, an estimated 17,000 people worldwide died from behavior related to or caused by schizophrenia. There is also a higher-than-average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia.

The term for schizophrenia in Japan was changed from “mind-split disease” to “integration disorder” to reduce stigma. The new name was inspired by the biopsychosocial model; it increased the percentage of people who were informed of the diagnosis from 37% to 70% over three years. A similar change was made in South Korea in 2012. A professor of psychiatry, Jim van Os, has proposed changing the English term to “psychosis spectrum syndrome”. In the United States, the cost of schizophrenia—including direct costs (outpatient, inpatient, drugs, and long-term care) and non-health care costs (law enforcement, reduced workplace productivity, and unemployment) doubled between 2013 and 2019 to $343.2 billion in 2019 (Kadakia et al. 2022) calling attention to the need for better strategies and treatments for this at-risk population.

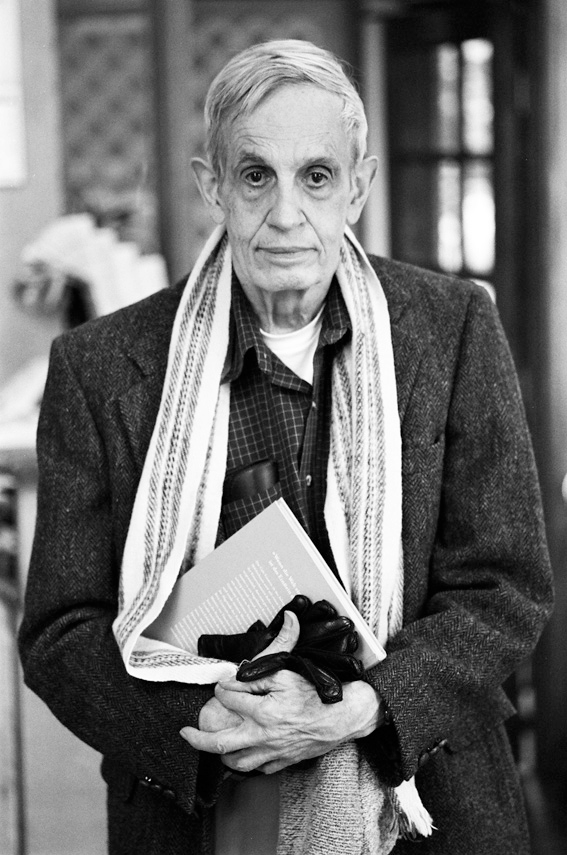

John Forbes Nash Jr., an American mathematician and joint recipient of the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics, had schizophrenia. His life was the subject of the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind.

Individuals with severe mental illness, including schizophrenia, are at a significantly greater risk of being victims of both violent and non-violent crimes. Schizophrenia has been associated with a higher rate of violent acts, but most appear to be related to associated substance abuse. Media coverage relating to violent acts by individuals with schizophrenia reinforces public perception of an association between schizophrenia and violence.

Mental Illness: Barriers to Treatment

Mental disorders are common, affecting tens of millions of people each year. Worldwide, more than one in three people in most countries report sufficient criteria for at least one at some point in their lives. In the United States, 46% qualify for a mental illness within their lifetime, with less than 1 out of 5 receiving a diagnosis. An ongoing survey indicates that anxiety disorders are the most common in all but one country, followed by mood disorders in all but two countries, while substance disorders and impulse-control disorders were consistently less prevalent. Estimates suggest that less than half of the people with mental illnesses in industrialized societies will receive treatment.

The World Health Organization (2025) updated guidance for countries on how to better address mental health. The WHO reports that globally, there is limited access to mental healthcare for the following reasons:

- Limited access to quality community-based mental health services, services are unavailable, inaccessible, unaffordable, or of poor quality

- Human rights violations, including coercive practices, denial of legal capacity, and institutionalization (includes overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate food physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and neglect)

- Over-reliance on the biomedical approach and psychotropic drugs

- Failure to address social and structural determinants to understand root causes of mental ill health

- Poor coordination between mental and physical health services people so those with mental health conditions have often had their physical health neglected for decades

- Underfunding of mental health services, including staffing, and inadequate training

Mental Illness: Cost to Society

This leads us to consider the cost of mental illness to society. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) indicates that depression is the number one cause of disability across the world, costing the global economy $1 trillion in lost productivity each year. Serious mental illness costs the United States an estimated $193 billion in lost earnings each year. NAMI also reports that suicide is the 12th leading cause of death in the U.S., and 90% of those who die from suicide have an underlying mental illness. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 10-14 and the third leading cause of death among those aged 15-24 in the U.S. Transgender adults are nearly 9x more likely to attempt suicide at some point in their lifetime compared to the general population, and 70% of youth in state and local juvenile justice systems have at least one mental disorder. In terms of worldwide impact, Arias et al. (2022) estimate that the economic cost of mental ill health and disability-adjusted life years will grow to nearly 5 trillion by 2030. Arias et al. also emphasize the need for research to incorporate the impact of evolving threats to global mental health, such as pandemics, wars, and climate change. In terms of worldwide impact, the costs of mental illness are greater than the combined costs of cancer, diabetes, and respiratory disorders (Whiteford et al., 2013).

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- image-9a73ac96-514c-40e1-9471-2683f6b2cd93 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- image-ba910e69-63e0-4dea-9878-3db0569ca594 © Peter Badge is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license