10.3 Trauma

“After all, when a stone is dropped into a pond, the water continues quivering even after the stone has sunk to the bottom.”

Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha

In psychology, trauma is a type of damage to the psyche that occurs as a result of a severely distressing event. Trauma is often the result of an overwhelming amount of stress that exceeds one’s ability to cope or integrate the emotions involved with that experience. A traumatic event can involve one experience or repeated events or experiences over time.

Traumatic, stressful events can have a long-term impact on mental and physical health. Individuals exposed to a severely stressful experience involving threat of death, injury, or sexual violence may develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). With this disorder, the trauma experienced is severe enough to cause stress responses for months or even years after the initial incident. The trauma overwhelms the victim’s ability to cope psychologically, and memories of the event trigger anxiety and physical stress responses, including the release of cortisol. People with PTSD may experience flashbacks, panic attacks, anxiety, and hypervigilance (extreme attunement to stimuli that remind them of the initial incident).

Stress and the Immune System

In a sense, the immune system is the body’s surveillance system. It consists of various structures, cells, and mechanisms that protect the body from invading toxins and microorganisms that can harm or damage the body’s tissues and organs. When the immune system works as it should, it keeps us healthy and disease-free by eliminating bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that have entered the body (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Whether stress and negative emotional states can influence immune function has captivated researchers for over three decades, and discoveries made over that time have dramatically changed the face of health psychology (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2009). Psychoneuroimmunology is the field that studies how psychological factors, such as stress, influence the immune system and immune functioning. The term psychoneuroimmunology was first coined in 1981, when it appeared as the title of a book that reviewed available evidence for associations between the brain, endocrine, and immune systems (Zacharie, 2009). To a large extent, this field evolved from discovering a connection between the central nervous system and the immune system.

Some of the most compelling evidence for a connection between the brain and the immune system comes from studies in which researchers demonstrated that animal immune responses could be classically conditioned (Everly & Lating, 2002). For example, Ader and Cohen (1975) paired flavored water (the conditioned stimulus) with the presentation of an immunosuppressive drug (the unconditioned stimulus), causing sickness (an unconditioned response). Not surprisingly, rats exposed to this pairing developed a conditioned aversion to the flavored water. However, the taste of the water itself later produced immunosuppression (a conditioned response), indicating that the immune system itself had been conditioned. Many subsequent studies have further demonstrated that immune responses can be classically conditioned in both animals and humans (Ader & Cohen, 2001). Thus, if classical conditioning can alter immunity, other psychological factors should also be capable of altering it.

Hundreds of studies involving tens of thousands of participants have tested many kinds of brief and chronic stressors and their effect on the immune system (e.g., public speaking, medical school examinations, unemployment, marital discord, divorce, death of spouse, burnout and job strain, caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s disease, and exposure to the harsh climate of Antarctica). Research has repeatedly demonstrated that many stressors are associated with poor or weakened immune functioning (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

When evaluating these findings, it is essential to remember that there is a tangible physiological connection between the brain and the immune system. For example, the sympathetic nervous system innervates immune organs such as the thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes (Maier et al., 1994). Also, stress hormones released during hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation can adversely impact immune function. One way they do this is by inhibiting the production of lymphocytes, white blood cells that circulate in the body’s fluids and are important in the immune response (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Some more dramatic examples demonstrating the link between stress and impaired immune function involve studies in which volunteers were exposed to viruses. The rationale behind this research is that because stress weakens the immune system, people with high stress levels should be more likely to develop an illness compared to those under little stress. In one memorable experiment using this method, researchers interviewed 276 healthy volunteers about recent stressful experiences (Cohen et al., 1998). Following the interview, these participants were given nasal drops containing the cold virus (in case you are wondering, researchers paid participants $800 to be involved). When examined later, participants who reported experiencing chronic stressors for more than one month, especially enduring difficulties involving work or relationships, were considerably more likely to have developed colds than were participants who reported no chronic stressors.

Toxic Stress Derails Healthy Development (open YouTube video in new tab)

How Trauma Affects The Brain

There is no shortage of information regarding how trauma affects brain development, but very basically, “when a stressful experience (such as abuse, neglect, or bullying) overwhelms the child’s natural ability to cope,” this can cause a “fight, flight, or freeze” response. This response results in changes in the body, including an accelerated heart rate and higher blood pressure. This physiological response also changes how the brain “perceives and responds to the world”. The result of this can be that the “trauma interferes with normal development and can have long-lasting effects” (above information from Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014, p. 2).

Stress in Early Childhood

What is the impact of stress on child development? The answer to that question is complex and depends on several factors, including the number of stressors, the duration of the stress, and the child’s ability to cope.

Children experience different types of stressors that could be manifested in various ways. Every day stress can allow young children to build coping skills and poses little risk to development. Children can even manage long-lasting stressful events (e.g., changing schools or losing a loved one).

Some experts have theorized that there is a point where prolonged or excessive stress becomes harmful and can lead to serious health effects. When stress builds up in early childhood, neurobiological factors are affected; in turn, levels of the stress hormone cortisol exceed normal ranges. Due in part to the biological consequences of excessive cortisol, children can develop physical, emotional, and social symptoms. Physical conditions include cardiovascular problems, skin conditions, susceptibility to viruses, headaches, or stomach aches in young children. Emotionally, children may become anxious or depressed, violent, or feel overwhelmed. Socially, they may become withdrawn, act out towards others, or develop new behavioral tics such as biting nails or picking at skin. Young children exposed to toxic stress are at risk of developing physical, emotional, and social symptoms.

Types of Stress

Researchers have proposed three distinct types of responses to stress in young children: positive, tolerable, and toxic. Positive stress (also called eustress) is necessary and promotes resilience, or the ability to function competently under threat. Such stress arises from brief, mild to moderate stressful experiences, buffered by the presence of a caring adult who can help the child cope with the stressor. This type of stress causes minor, temporary physiological and hormonal changes in the young child, such as an increased heart rate and a change in the hormone cortisol levels. The first day of school, a family wedding, or making new friends are all examples of positive stressors. Tolerable stress comes from adverse experiences that are more intense but short-lived and can usually be overcome. Some examples of tolerable stressors are family disruptions, accidents, or the death of a loved one. The body’s stress response is more intensely activated due to severe stressors; however, the response is still adaptive and temporary.

Toxic stress is a term coined by pediatrician Jack P. Shonkoff of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University to refer to chronic, excessive stress that exceeds a child’s ability to cope, especially in the absence of supportive care-giving from adults.

Extreme, long-lasting stress in the absence of supportive relationships to buffer the effects of a heightened stress response can produce damage and weakening of bodily and brain systems, which can lead to diminished physical and mental health throughout a person’s lifetime. Exposure to such toxic stress can result in the stress response system becoming more highly sensitized to stressful events, producing increased wear and tear on physical systems through over-activation of the body’s stress response. This wear and tear increases the later risk of various physical and mental illnesses.

Intergenerational Trauma

Intergenerational trauma is trauma that can be transferred from the first generation of trauma survivors to the second and further generations of offspring of the survivors via complex post-traumatic stress disorder mechanisms.

Soon after descriptions of concentration camp syndrome (also known as survivor syndrome) appeared, clinicians observed in 1966 that large numbers of children of Holocaust survivors were seeking treatment in clinics in Canada (Fossion et al., 2003). The grandchildren of Holocaust survivors were overrepresented by 300% among the referrals to a child psychiatry clinic in comparison with their representation in the general population.

The phenomenon of children of traumatized parents being affected directly or indirectly by their parents’ post-traumatic symptoms has been described by some authors as secondary traumatization (in reference to the second generation). To include the third generation, as well, the term intergenerational transmission of trauma was introduced.

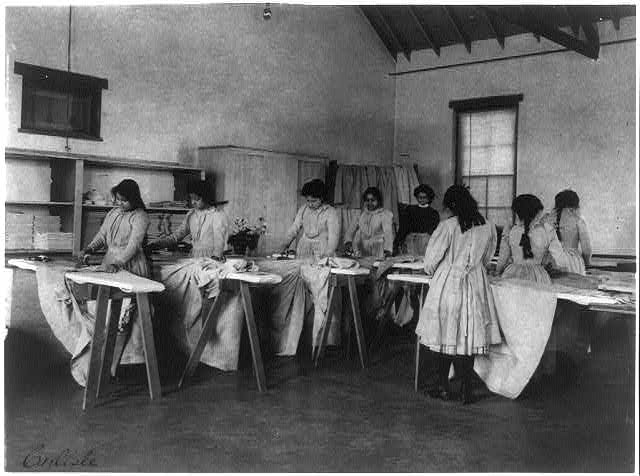

Symptoms of transgenerational trauma have in recent years been identified among African Americans, concerning the effects of slavery and racial discrimination, and by Native Americans, concerning the impact of cultural genocide experienced by their ancestors and current discrimination and marginalization from mainstream society. This passing of trauma can be rooted in the family unit itself or found in society via current discrimination and oppression. The traumatic event does not need to be individually experienced by all family members; the lasting effects can remain and impact descendants from external factors.

Instances of transgenerational trauma where the trauma affects a large population of people and their role in society can be identified as cultural trauma. This form of trauma results in a greater loss of identity and meaning, which in turn affects generations upon generations as the trauma is ingrained into society. This passing of psychological and emotional trauma from slavery, for example, has also been identified as post-traumatic slave syndrome (PTSS). According to Dr. Joy DeGruy Leary, PTSS is when a population experiences intergenerational trauma from centuries of psychological and emotional enslavement and continues to face institutionalized oppression and racism. Black Americans who are descendants of formerly enslaved people, when faced with racism and oppression, have reactions that mirror those of PTSD. DeGruy theorizes that PTSS is directly responsible for other dangers and origins of harm in the Black community. The internalized harm caused by PTSS is manifested in external behaviors, allowing the rest of society to use the effects and symptoms of PTSS as stereotypes against Black people, thus exacerbating the racial trauma and moving forward the cycle.

Enslavement and slavery, civil and domestic violence, sexual abuse, and extreme poverty are also sources of trauma that can be transferred to subsequent generations. For instance, survivors of child sexual abuse may negatively influence future generations due to past untreated or unresolved trauma. This trauma can lead to increased feelings of mistrust, isolation, and loneliness. Descendants of enslaved people, when faced with racism-motivated violence, microaggressions, or outward racism, react as if they were faced with the original trauma that was generationally transmitted to them. There are a variety of stressors in one’s life that lead to this PTSD-like reaction, such as varying racist experiences, daily microstressors, major race-related life events, or collective racism or traumas. This also presents itself in parenting styles. Parents who not only receive the trauma genetically but also experience stressors frequently may create a home environment that deflects the stress they experience, adding to the inherent stress of the child. Goodman and West-Olatunji (2008) proposed potential transgenerational trauma in the aftermath of natural disasters. In a post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, residents have seen a dramatic increase in interpersonal violence with higher mortality rates.

This phenomenon has been reported in the descendants of Native American students at residential schools, who were removed from their parents and extended family and lacked models for parenting as a result. Being punished for speaking their native language and forbidden from practicing traditional rituals had a traumatic effect on many students, and child abuse was rampant in the schools as well.

Treatment

A number of psychotherapies have demonstrated usefulness in the treatment of PTSD and other trauma-related problems. Basic counseling practices common to many treatment responses for PTSD include education about the condition and provision of safety and support. The psychotherapy programs with the strongest demonstrated efficacy include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), variants of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training (SIT), variants of cognitive therapy (CT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and many combinations of these procedures.

EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) were recommended as first-line treatments for trauma victims in a 2007 review (Bisson et al., 2007). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) seeks to change the way a trauma victim feels and acts by changing the patterns of thinking and/or behavior responsible for negative emotions. In CBT, individuals learn to identify thoughts that make them feel afraid or upset and replace them with less distressing thoughts. The goal is to understand how certain thoughts about events cause PTSD-related stress.

A variety of medications have shown adjunctive benefit in reducing PTSD symptoms; however, there is no clear drug treatment for PTSD. Positive symptoms (those that most individuals do not normally experience but are present in people with PTSD, such as re-experiencing or increased arousal) generally respond better to medication than negative symptoms (deficits of normal emotional responses or thought processes, such as avoidance or withdrawal)

Key Takeaways

Psychological disorders are conditions characterized by abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Although challenging, it is essential for psychologists and mental health professionals to agree on what kinds of inner experiences and behaviors constitute the presence of a psychological disorder. Inner experiences and behaviors that are atypical or violate social norms could signify the presence of a disorder; however, each of these criteria alone is inadequate. Harmful dysfunction describes the view that psychological disorders result from the inability of an internal mechanism to perform its natural function. Many of the features of harmful dysfunction conceptualization have been incorporated in the APA’s formal definition of psychological disorders. According to this definition, the presence of a psychological disorder is signaled by significant disturbances in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; these disturbances must reflect some kind of dysfunction (biological, psychological, or developmental), must cause significant impairment in one’s life, and must not reflect culturally expected reactions to certain life events.

Media Attributions

- pexels-alex-green-5700155 © Alex Green is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- pexels-matvalina-18744639 © Alina Matveycheva is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- pexels-aadil-1764445 (1) © Aa Dil is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- pexels-pixabay-236215

- pexels-theerl-14105480 © Erlan is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- carlisle-indian-school-carlisle-pa-ironing-class (1) is licensed under a Public Domain license