14.2 Acculturation

Acculturation is the process of social, psychological, and cultural change that occurs as a result of blending between cultures. Immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and sojourners are typically the people we think of as having to adapt to a new culture (Schwartz et al., 2010), but it can happen to anyone who enters a new culture and must adjust to new norms, values, and systems. We learned earlier that enculturation is the process through which we first learn about a culture, and we can think of acculturation as the process of learning about a second culture.

The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels in both the original (native) and newly adopted (host) cultures. At the group level, acculturation often results in changes to culture, customs, religious practices, diet, healthcare, and other social institutions. Some of the most noticeable group-level effects of acculturation include changes in food, clothing, and language. At the individual level, the process of acculturation refers to the socialization process by which people adopt the values, customs, norms, attitudes, and behaviors of a host culture. This process has been linked to changes in daily behavior, as well as numerous changes in psychological and physical well-being.

Four Effects of Diffusion (open YouTube video in new tab)

As part of the acculturation process, individuals may experience culture shock, which can be defined as the personal disorientation a person may feel when experiencing an unfamiliar way of life due to immigration or a visit to a new country, or due to a move between social environments. One of the most common causes of culture shock involves individuals in a foreign country. There is no true way to entirely prevent culture shock, as individuals in any society are personally affected by cultural contrasts differently.

Commonly associated issues of culture shock include: loss of status (e.g., going from provider to unemployed), unfamiliar social systems and social norms (e.g., agencies rather than extended kin networks), distance from family and friends, information overload, language barriers, generation gap, and possible technology gap.

The Four Phases of Culture Shock

There is no way to prevent culture shock because everyone experiences and reacts to the contrasts between cultures differently. Culture shock can be described as consisting of at least one of four distinct phases: honeymoon, negotiation, adjustment, and mastery.

The Honeymoon Phase

During the honeymoon phase, the differences between the old and new cultures are seen in a romantic light. During the first few weeks, most people are fascinated by the new culture. They associate with nationals who speak their language and who are polite to foreigners. This period is full of observations and new discoveries. Like most honeymoon periods, this stage eventually ends.

The Negotiation Phase

After some time (usually around three months, depending on the individual), differences between the old and new culture become apparent and may create anxiety. This is the mark of the negotiation phase. Excitement may eventually give way to unpleasant feelings of frustration and anger as one continues to experience unfavorable events that may be perceived as strange and offensive to one’s cultural attitude. Language barriers, stark differences in public hygiene, traffic safety, food accessibility, and quality may heighten the feelings of disconnection from the surroundings.

Living in a different environment can have a negative, although usually short-term, effect on our health. While negotiating culture shock, we may have insomnia because of circadian rhythm disruption, problems with digestion because of gut flora due to different bacteria levels and concentrations in food and water, and difficulty in accessing healthcare or treatment (e.g., medicines with different names or active ingredients).

During the negotiation phase, people adjusting to a new culture often feel lonely and homesick because they are not yet used to the new environment and encounter unfamiliar people, customs, and norms every day. The language barrier may become a major obstacle in creating new relationships. Some individuals find that they must pay special attention to culturally specific body language (e.g., arms crossed, smiling), conversation tone, and linguistic nuances and customs (e.g, handshake, turn-taking, ending a conversation). International students often feel anxious and feel more pressure while adjusting to new cultures because there is special emphasis on their reading and writing skills

The Adjustment Phase

Again, after some time, one grows accustomed to the new culture and develops routines, marking the adjustment phase. One knows what to expect in most situations, and the host country no longer feels all that new. One becomes concerned with basic living again, and things become more normal. One starts to develop problem-solving skills for dealing with the culture and begins to accept the culture’s ways with a positive attitude. The culture begins to make sense, and negative reactions and responses to the culture are reduced.

The Mastery Phase

In the mastery stage, individuals are able to participate fully and comfortably in the host culture. Mastery does not mean total conversion. People often keep many traits from their earlier culture, such as accents and languages. It is often referred to as the biculturalism stage.

Berry’s Model of Acculturation

Culture shock and the stages of culture shock are part of the acculturation process. Scholars in different disciplines have developed more than 100 different theories of acculturation (Rudiman, 2003); however, contemporary research has primarily focused on different strategies and how acculturation affects individuals, as well as interventions to make the process easier (Berry, 1997).

Berry proposed a model of acculturation that categorizes individual adaptation strategies along two dimensions (Berry, 1997).

- The first dimension concerns the retention or rejection of an individual’s native culture (i.e., “Is it considered to be of value to maintain one’s identity and characteristics?”).

- The second dimension concerns the adoption or rejection of the host culture. (“Is it considered to be of value to maintain relationships with the larger society?”)

The second dimension concerns the adoption or rejection of the host culture. (“Is it considered to be of value to maintain relationships with the larger society?”) From these two questions, four acculturation strategies emerge:

- Assimilation occurs when individuals adopt the cultural norms of a dominant or host culture over their original culture.

- Separation occurs when individuals reject the dominant or host culture in favor of preserving their culture of origin. Separation is often facilitated by immigration to ethnic enclaves.

- Integration occurs when individuals are able to adopt the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture while maintaining their culture of origin. Integration leads to, and is often synonymous with, biculturalism.

- Marginalization occurs when individuals reject both their culture of origin and the dominant host culture.

Studies suggest that the acculturation strategy people use can differ between their private and public areas of life (Arends-Tóth & van de Vijver, 2004). For instance, an individual may reject the values and norms of the host culture in his private life (separation), but he might adapt to the host culture in public parts of his life (i.e., integration or assimilation). Moreover, attitudes towards acculturation and the different acculturation strategies available have not been consistent over time. For example, for most of American history, policies and attitudes have been based around established ethnic hierarchies with an expectation of one-way assimilation for predominantly white European immigrants (Fredrickson, 1999).

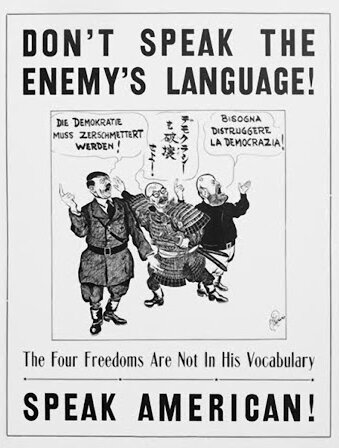

The history of immigration in the United States is also tied to the way that race has been constructed. The metaphor of the melting pot has been used to describe the immigration history of the United States, but it doesn’t capture the experiences of many immigrant groups. Generally, immigrant groups who were white, or light-skinned, and spoke English were better able to assimilate or melt into the melting pot. But immigrant groups that we might think of as white today were not always considered so. Irish immigrants were discriminated against and even portrayed as black in cartoons that appeared in newspapers. In some Southern states, Italian immigrants were forced to go to black schools, and it wasn’t until 1952 that Asian immigrants were allowed to become citizens of the United States. All this history is important because it continues to influence communication among races today.

Around the globe, monolingual speakers are the minority. Yet those who do not speak English when immigrating to the U.S. may struggle to acculturate until the language is learned.

Within the United States, separation as an acculturation strategy can still be seen today in some religious communities such as the Amish and the Hutterites. An integration strategy for acculturation can be observed within Deaf culture. Individuals who are deaf use a different language to communicate, learn about their culture and language from institutions and not their family (most deaf children have hearing parents), and are united by shared experiences as persons with disabilities. Deaf individuals in the United States live within the dominant culture and share the same cultural values, but are separated by language and disability (Maxwell-McCaw et al., 2000). Members of the Deaf culture have created their own unique cultural and social norms for communicating, interacting, and experiencing the world around them.

Immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and sojourners are typically the individuals we think of as having to adapt to a new culture, but individuals within the United States may also acculturate.

Some acculturation research suggests that the integrated acculturation strategy has the most favorable psychological outcomes (Nguyen et al., 2007; Okasaki et al., 2009) for individuals adjusting to a host culture, and marginalization has the least favorable outcomes (Berry et al., 2006). Additionally, marginalization has been described as a maladaptive acculturation and coping strategy (Knust et al., 2013). Other researchers have argued that the four strategies have very little predictive validity because people do not always fall neatly into the four categories (Kunst et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2010). Situational determinants (e.g., traveling with family, familiarity with language) and environmental factors also impact the availability, advantage, and selection of different acculturation strategies (Zhou, 1997).

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- Statue of Liberty at Sunset by Line Knipst is licensed CC BY from Pexels © Line Knipst is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- USMC-090804-M-4453-002 © Lance Cpl. Noel Gonzalez is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Don’t_Speak_the_Enemy’s_Language,_Speak_American © US Government is licensed under a Public Domain license

- pexels-simon-hurry-50614850-9459922 © Simon Hurry is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license