3.2 Research Issues in Cultural Psychology

Research Issues in Cultural Psychology

Research methods are used in a psychological investigation (experiment) to describe and explain psychological phenomena and constructs. Research methods can also predict and control issues through objective and systematic analysis. Information, sometimes called data, for psychological research can be collected from different sources like human participants (e.g., surveys, interviews), animal studies (e.g., learning and behavior), and archival sources (e.g., tweets, social media posts). Research is done through observation, analysis, and comparison with the help of an experiment.

Considerations in Research

When conducting research within a culture (indigenous study) or across cultures (cross-cultural study), many things can go wrong, making conducting, analyzing, and interpreting data difficult. This section will review four common methodological issues in cultural research (He & van de Vijver, 2012):

- Sampling Bias

- Procedural Bias

- Instrument Bias

- Interpretation Bias

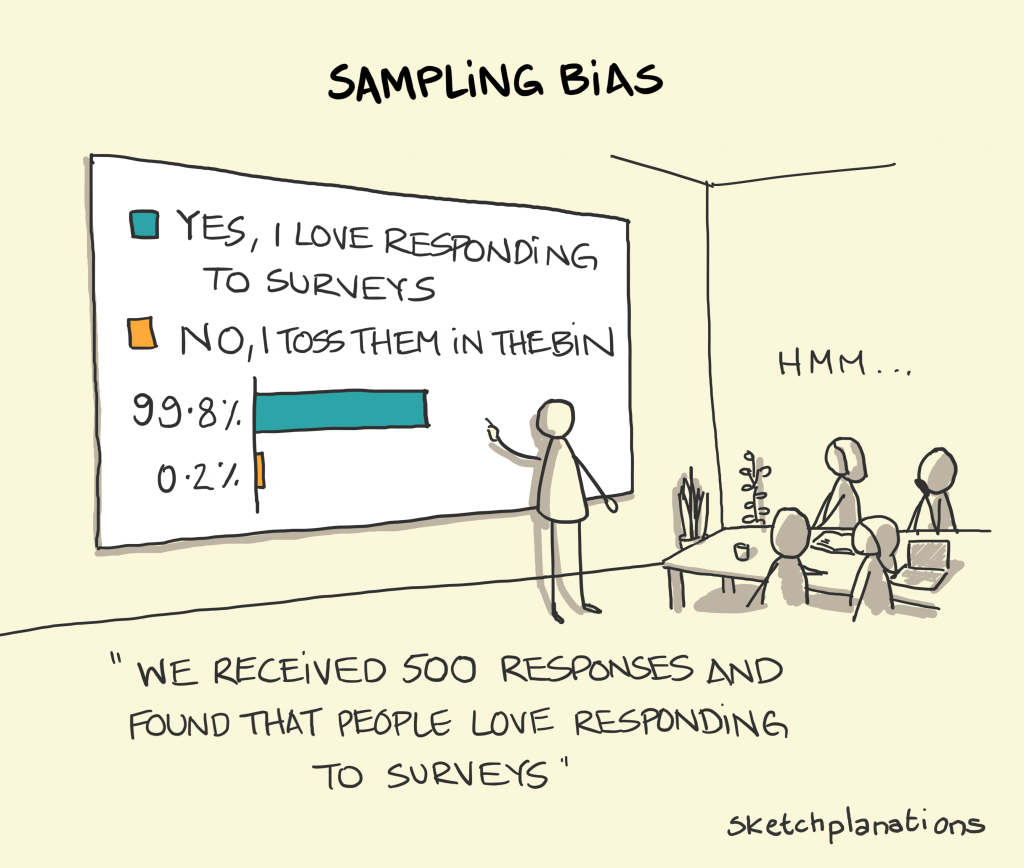

Sampling Bias

Recruiting undergraduate students to participate in psychological research studies is common in the United States and other Western countries. Using samples of convenience from this very thin slice of humanity presents a problem when trying to generalize to the larger public and across cultures. Aside from being an over-representation of young, middle-class Caucasians, college students may also be more compliant and more susceptible to attitude change, have less stable personality traits and interpersonal relationships, and possess stronger cognitive skills than samples reflecting a wider range of age and experience (Peterson & Merunka, 2014; Visser et al., 2000).

These traditional samples (college students) may not sufficiently represent the broader population. Furthermore, considering that 96% of participants in psychology studies come from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries (so-called WEIRD cultures; Henrich et al., 2010) and that most of these are also psychology students, the question of non-representativeness becomes even more serious.

How confident can we be that the results of social psychology studies generalize to the broader population if participants are primarily of the WEIRD variety?

A non-representative sample may not be a big deal when studying a fundamental cognitive process (e.g., working memory) or an aspect of social behavior that appears fairly universal (e.g., cooperation). Still, research has repeatedly demonstrated the critical role that individual differences (e.g., personality traits and cognitive abilities) and culture (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) play in shaping social behavior.

For instance, even if we only consider a tiny sample of research on aggression, we know that narcissists are more likely to respond to criticism with aggression (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998); conservatives, who have a low tolerance for uncertainty, are more likely to prefer aggressive actions against those considered to be “outsiders” (de Zavala et al., 2010); countries where men hold the bulk of power in society have higher rates of physical aggression directed against female partners (Archer, 2006); and males from the southern part of the United States are more likely to react with aggression following an insult (Cohen et al., 1996).

When conducting research across cultures, ensuring equivalence across samples from other cultures is essential to maintain the research study’s internal consistency (validity) (Harzing et al., 2013; Matsumoto & Juang, 2013). Asking middle-school students in the United States about their online shopping experiences may not be a representative sample of middle school students in Kenya. Even when trying to control for demographic differences, some experiences cannot be separated from culture (Matsumoto and Luang, 2013). For example, being Catholic in the United States does not have the same meaning as being Catholic in Japan or Brazil. Researchers must consider the experiences of the sample in addition to basic demographic information.

Example 1: Japanese mosaic of Madonna and Child in the upper-level chapel of the Church of the Annunciation, Nazareth, Israel. The depiction of Madonna and Child reflects their unique cultural differences and practices.

Example 2: Tuscan artwork of Madonna and Child. The depiction of Madonna and Child reflects their unique cultural differences and practices.

Procedural Bias

Another type of methodological bias is procedural bias, sometimes called administration bias. This bias is related to the study conditions, including the setting and how the instruments are administered across cultures (He & van de Vijver, 2012). The interaction between the research participant and interviewer is another type of procedural bias that can interfere with cultural comparisons. For example, a study comparing attitudes toward mental health treatment in different countries might encounter procedural bias if participants in one country are interviewed in person while participants in another country complete an online survey. Differences in response rates and comfort levels with these methods could influence the findings, making cross-cultural comparisons less reliable.

Reducing procedural bias requires careful planning, standardization of procedures, and cultural sensitivity to ensure that study conditions are as similar as possible across research sites.

Setting

Where the study is conducted can significantly influence how the data is collected, analyzed, and later interpreted. Settings can be small (e.g., home or community center), or settings can be significant (e.g., countries or regions). They can influence how a survey is administered or how participants might respond. In a sizeable cross-cultural health study, Steels and colleagues (2014) found that the postal system in Vietnam was unreliable and demanded a significant and unexpected change in survey methodology. Due to these challenges, the researchers were forced to use more participants from urban than rural areas. Harzing et al. (2013) found that their online survey was blocked in China due to Internet censoring practices of the Chinese government. Still, with minor changes, it was later made available for administration.

Problems with infrastructure and services may limit research participation.

Instrument Administration

In addition to the setting, how the data is collected (e.g., paper-and-pencil mode versus online survey) may influence different levels of social desirability and response rates. Dwight and Feigelson (2000) completed a computerized testing meta-analysis on socially desirable responses and found that impression management (one dimension of social desirability) was lower in online assessment. The impact was small, but it does have broad implications for how results are interpreted and compared across cultural groups when testing occurs online.

How you take a survey or test may influence how you respond to certain types of questions.

Harzing et al. (2013) found that paper/pencil surveys were overwhelmingly preferred by their participants, a sample of international human resource managers, and had much higher response rates when compared to the online survey. It is important to note that online survey response rates were likely higher in Japan and Korea primarily because of difficulties in photocopying and mailing paper versions of the survey.

Interviewer and Interviewee Issues

The interviewer effect can easily occur when there are communication problems between interviewers and interviewees, especially when they have different first languages and cultural backgrounds (van de Vijver and Tanzer, 2004). Interviewers unfamiliar with cultural norms and values may unintentionally offend participants or colleagues or compromise the integrity of the study. Davis and Silver (2003) summarized an example of the interviewer effect. The researchers found that when answering questions regarding political knowledge, African American respondents got fewer answers right when interviewed by a European American interviewer than by an African American interviewer.

Administrative conditions that can lead to bias should be considered before beginning the research, and researchers should exercise caution when interpreting and generalizing results. Using a translator is not a guarantee that interviewer bias will be reduced. Translators may unintentionally change the intent of a question or item by omitting, revising, or reducing content. These language changes can alter the intent or nuance of a survey item (Berman, 2011), which will alter the answer provided by the participant.

A translator or interpreter can unintentionally change a question, which may change how a participant responds.

Instrument Bias

A final type of method bias is called instrument bias. It does not have anything to do with the instrument, survey, or test; rather, it refers to the experience and familiarity of the participant with test-taking. There are two main types of instrument bias discussed in cross-cultural research (He & van de Vijver, 2012):

- Familiarity with the type of test (e.g., cognitive versus educational), and

- Familiarity with response methods (e.g., multiple choice or rating scales).

Demetriou and colleagues described an example of familiarity with test type (2005) when they compared Chinese and Greek children on visual-spatial tasks. The researchers found that Chinese children outperformed Greek children on the task, not because of cultural differences in visual-spatial performance, but because writing Chinese is a visual-spatial task. Chinese children performed better because learning to write (in all cultures) requires practice and writing. However, learning the Chinese language is a highly visual-spatial task.

Using a Scranton answer sheet assumes participants use the same lettering system.

An example of how instrument bias can be reduced comes from a study that included Zambian and British children (Serpell, 1979). The children were asked to reproduce a pattern using several different response methods, including paper-and-pencil, plasticine, configurations of hand positions, and iron wire. The British children scored significantly higher on the paper-and-pencil method, while the Zambians scored higher using iron wires (Serpell, 1979). These results make sense within cultural contexts. Paper-and-pencil testing is a common experience in formal Western education systems, and creating models with iron wire was a popular pastime among Zambian children. By using different response methods (i.e., paper/pencil, iron wire), the researchers could separate performance from bias related to response methods.

Whether or not someone is familiar with a type of test will influence how well the person performs.

Another issue related to instrument bias is response bias, which is the systematic tendency to respond in a certain way to items or questions. Many things may lead to response bias, including how survey questions are phrased, the researcher’s demeanor, or the participant’s desire to be a good participant and provide “the right’ answers. There are three common types of response bias:

- Socially desirable responding (SDR) is the tendency to respond in a way that makes you look good. Studies that examine sensitive topics (e.g., sexuality, sexual behaviors, mental health) or behaviors that violate social norms (e.g., fetishes, binge drinking, smoking, and drug use) are particularly susceptible to SDR.

- Acquiescence bias is the tendency to agree rather than disagree with items on a questionnaire. It can also mean agreeing with statements when unsure or in doubt. Studies have consistently shown that acquiescence response bias occurs more frequently among participants from low socioeconomic status and collectivist cultures (Harzing, 2006; Smith & Fischer, 2008). Additionally, work by Ross and Mirowsky (1984) found that Mexicans were more likely to engage in acquiescence and socially desirable responses than European Americans on a survey about mental health.

- Extreme response bias is the tendency to use the ends of the scale (all high or all low values) regardless of what the items are asking or measuring. A demonstration of extreme response bias can be found in the work of Hui and Triandis (1989). These authors found that Hispanics tended to choose extremes on a five-point rating scale more often than European Americans, although no significant cross-cultural differences were found for 10-point scales.

Interpretation Bias

One problem with cross-cultural studies is that they are vulnerable to ethnocentric bias. This means that the researcher who designs the study might be influenced by personal biases that could affect research outcomes without being aware of it. For example, a study on happiness across cultures might investigate how individual freedom is associated with feeling a sense of purpose in life. The researcher might assume that when people are free to choose their work and leisure, they are more likely to pick options they care deeply about. Unfortunately, this researcher might overlook that in much of the world, it is considered essential to sacrifice some personal freedom to fulfill one’s duty to the group (Triandis, 1995). Because of the danger of this type of bias, cultural psychologists must continue to improve their methodology.

Another problem with cross-cultural studies is that they are susceptible to the cultural attribution fallacy. This happens when the researcher concludes that there are fundamental cultural differences between groups without any actual support for this conclusion. Yoo (2013) explains that if a researcher concludes that two countries are different based on a psychological construct because one country is an individualistic (I) culture and the other is a collectivist (C) culture, without connecting differences to IC, then the researcher has made a cultural attribution fallacy.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- Interviewing_indigenous_woman_in_Guatemala © Jody Santos is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- sketchplanations-sampling-bias © Sketchplanations is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license

- 4223-20080119-0633UTC–nazareth-church-of-the-annunciation-japanese-madonna © adriatikus is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- ‘Madonna_and_Child’,_tempera_and_gold_on_wood_panel_by_a_master_of_the_School_of_Lucca,_ca._1200,_El_Paso_Museum_of_Art is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Transfeminine and non-binary colleagues talking in an office © Gender Spectrum Collection is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- pexels-shvets-production-7516574 © SHVETS Production is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- nguyen-dang-hoang-nhu-qDgTQOYk6B8-unsplash (1) © Nguyen Dang is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license