4.3 The Role of Parenting in Cultural Development

Differences in parenting reflect differences in parenting goals, values, resources, and experiences.

Culture is learned. Regardless of the specific choices parents make, caretakers play a pivotal role in exposing a child to early cultural learning. Many researchers believe parents/caretakers are the most crucial enculturation agents in any child’s life. While some parenting priorities are culturally universal (parents are expected to play a role in nurturing and raising their young), many more child-rearing values and habits are culture-specific. Culture-specific influences on care-taking choices can be subtle or overt and promote a narrative of what parents “ought” to do to raise their children successfully. For example, American parents are encouraged to enculturate a sense of independence and assertiveness in children, while Japanese parents prioritize self-control, emotional maturity, and interdependence (Bornstein, 2012). Undoubtedly, every society places expectations on caretakers as enculturation agents to raise their young in ways that promote culture-specific goals and expectations.

The Development of Parents

Psychologists have attempted to answer questions about the influences on parents and understand why parents behave the way they do. Because parents are critical to a child’s development, much research has focused on the impact of parents on children. Less is known, however, about the development of parents themselves and the impact of children on parents. Nonetheless, parenting plays a significant role in an adult’s life. Parenthood is often considered a normative developmental task of adulthood. Cross-cultural studies show that adolescents around the world plan to have children. Most men and women in the United States will become parents by the age of 40 (Martinez et al., 2018). People have children for many reasons, including emotional reasons (e.g., the emotional bond with children and the gratification the parent-child relationship brings), economic and utilitarian reasons (e.g., children provide help in the family and support in old age), and social-normative reasons (e.g., adults are expected to have children; children provide status) (Nauck, 2007).

Parenthood has a huge impact on a person’s identity, emotions, daily behaviors, and many other aspects of their lives.

Parenthood is undergoing changes in the United States and elsewhere in the world. Children are less likely to live with both parents, and women in the United States have fewer children than previously. The average fertility rate of women in the United States was about seven children in the early 1900s and has remained relatively stable at 2.1 since the 1970s (Hamilton et al., 2011; Martinez et al., 2012). In 2022, Census data shows the average number of children in US families is 1.94 (Osterman et al., 2024). Not only are parents having fewer children, but the context of parenthood has also changed. Parenting outside marriage has increased dramatically among most socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic groups (Osterman et al., 2024). However, college-educated women are substantially more likely to be married at the birth of a child than mothers with less education (Dye, 2010). Parenting is occurring outside of marriage for many economic and social reasons. People have children at later ages, too. Although young people are more often delaying childbearing, most 18- to 29-year-olds want to have children and say that being a good parent is one of the most essential things in life (Wang & Taylor, 2011). However, research notes that Millennials have been slower than previous generations to establish their own household. As of 2020, more than half of Millennials are unmarried, and those who married did so later in life (Barroso et al., 2020).

| Changes in Parenthood in the United States | 1960 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Average number of children (fertility rate) | 3.6 (*6) | 1.94 (*7) |

| Percent of births to unmarried women | 5% (*1) | 39.8% (*2) |

| Median age at first marriage for women | 20.8 years (*5) | 28.4 years (*3) |

| Percentage of adults ages 18 to 34 living with a spouse | 63% (*4) | 26% (*4) |

Influences on Parenting

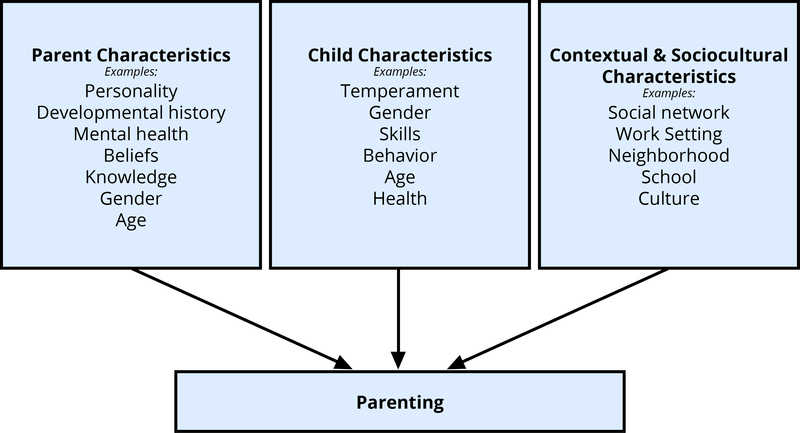

Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children influence one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parental behavior include 1) parent characteristics, 2) child characteristics, and 3) contextual and sociocultural characteristics (Belsky, 1984; Demick, 1999).

Many factors influence parenting decisions and behaviors. These factors include characteristics of the parent, such as gender and personality, as well as characteristics of the child, such as age. The context is also important. The interaction among all these factors creates many different patterns of parenting behavior. Furthermore, parenting influences not just a child’s development but also the development of the parent. As parents face new challenges, they change their parenting strategies and construct new aspects of their identity. The goals and tasks of parents change over time as their children develop.

Many contextual factors influence parenting. These include parent characteristics, child characteristics, and contextual and sociocultural characteristics.

Parent Characteristics

Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include the parents’ age, gender, beliefs, personality, developmental history, parenting and child development knowledge, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities affect parenting behaviors. Mothers and fathers who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more congenial, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable (Prinzie et al., 2009). Parents with these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment.

Parents’ developmental histories or experiences as children also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth were more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their children (Kerr et al., 2009). Patterns of hostile parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their parents’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods with their children.

Child Characteristics

Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children also influence their parents. Child characteristics, such as gender, birth order, temperament, and health status, affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an easy temperament infant may make parents feel more effective, as they can easily soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant elicits fewer positive reactions from his or her parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role (Eisenberg et al., 2008). Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children (Clark et al., 2000; Eisenberg et al., 1999; Kiff et al., 2011). Parents who have a fussy, difficult child are less satisfied with their marriages and have more significant challenges in balancing work and family roles (Hyde et al., 2004). Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the gender of the child. Parents respond differently to boys and girls. Parents often assign different household chores to their sons and daughters. Girls are frequently responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as lawn mowing (Grusec et al., 1996). Parents also talk differently with their sons and daughters, providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotional words with their daughters (Crowley et al., 2001).

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics

The parent-child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, also influence parenting. Parents who experience financial hardship are more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics affect their parenting skills (Conger & Conger, 2002). Culture also influences parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community is a universal goal of parenting, the required specific skills vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). For example, parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements, as well as goals involving maintaining harmonious relationships and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships. These differences in parental goals are influenced by culture and by immigration status. Other critical contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, also affect parenting, even though these settings don’t always include both the child and the parent (Bronfenbrenner, 1989). For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living in a threatening environment (Gonzales et al., 2011).

Parenting Styles & Attachment

As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to more significant parent-child conflict, and how parents manage conflict further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships. So, what can parents do to nurture a healthy self-concept in their children?

Attachment

This interaction can be observed in developing the earliest relationships between infants and their parents in the first year. Virtually all infants living in normal circumstances develop strong emotional attachments to those who care for them. Psychologists believe that developing these attachments is as biologically natural as learning to walk and not simply a byproduct of the parents’ provision of food or warmth. Rather, attachments have evolved in humans because they promote children’s motivation to stay close to those who care for them and, consequently, to benefit from the learning, security, guidance, warmth, and affirmation that close relationships provide (Cassidy, 2008).

Although nearly all infants develop emotional attachments to their caregivers–parents, relatives, nannies– their sense of security in those attachments varies. Infants become securely attached when their parents respond sensitively to them, reinforcing the infants’ confidence that their parents will provide support when needed. Infants become insecurely attached when care is inconsistent or neglectful; these infants tend to respond avoidantly, resistantly, or in a disorganized manner (Belsky & Pasco Fearon, 2008). Such insecure attachments are not necessarily the result of deliberately bad parenting but are often a byproduct of circumstances. For example, an overworked single mother may be overstressed and fatigued at the end of the day, making fully involved childcare very difficult. In other cases, some parents are poorly emotionally equipped to take on the responsibility of caring for a child.

Science Bulletins: Attachment Theory Understanding the Essential Bond (open YouTube video in new tab)

The different behaviors of securely- and insecurely-attached infants can be observed, especially when the infant needs the caregiver’s support. To assess the nature of attachment, researchers use a standard laboratory procedure called the “Strange Situation,” which involves brief separations from the caregiver (e.g., mother) (Solomon & George, 2008). In the Strange Situation, the caregiver is instructed to leave the child to play alone in a room for a short time, then return and greet the child while researchers observe the child’s response. Depending on the child’s level of attachment, he or she may reject the parent, cling to the parent, or welcome the parent, or, in some instances, react with an agitated combination of responses.

Infants can be securely or insecurely attached to mothers, fathers, and other regular caregivers, and they can differ in their security with different people. The security of attachment is an important cornerstone of social and personality development, because infants and young children who are securely attached have been found to develop stronger friendships with peers, more advanced emotional understanding and early conscience development, and more positive self-concepts, compared with insecurely attached children (Thompson, 2008). This is consistent with attachment theory’s premise that experiences of care, resulting in secure or insecure attachments, shape young children’s developing concepts of the self, what people are like, and how to interact with them.

The Strange Situation | Mary Ainsworth, 1969 | Developmental Psychology (open YouTube video in new tab)

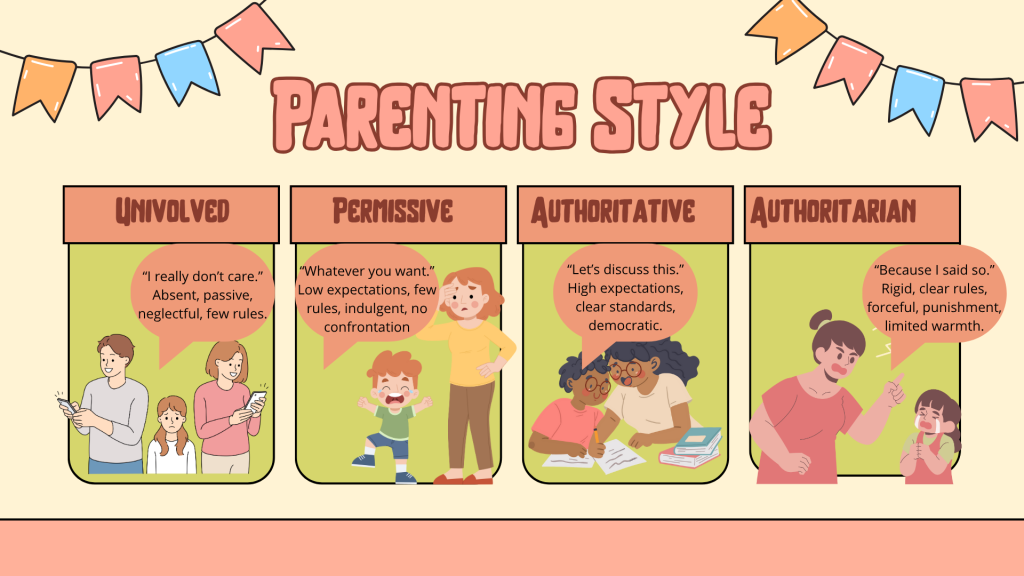

In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high (but reasonable) expectations for children’s behavior, communicate well with them, are warm and responsive, and use reasoning (rather than coercion) as preferred responses to children’s misbehavior. This parenting style has been described as authoritative (Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities, but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. By contrast, some less-constructive parent-child relationships result from authoritarian, uninvolved, or permissive parenting styles.

Parenting Styles

5 Parenting Styles and Their Effects on Life (open YouTube video in new tab)

Parenting styles are crucial in shaping a child’s emotional, social, and cognitive development. Developmental psychologists, including Diana Baumrind (1967), introduced a matrix to categorize parenting approaches based on two dimensions: responsiveness (warmth or supportiveness) and demandingness (control or discipline). This framework, later expanded by Maccoby and Martin (1983), outlines four primary parenting styles: authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful/uninvolved.

Authoritative Parenting

The authoritative parenting style is characterized by high responsiveness and high demandingness. Parents using this approach demonstrate warmth and responsiveness to their children’s needs while maintaining clear expectations and boundaries. They enforce rules consistently but remain flexible, allowing open communication and considering the child’s perspective. Discipline under authoritative parenting focuses on guiding behavior rather than punishment.

Research indicates that children raised by authoritative parents tend to develop high self-esteem, social competence, and emotional regulation and perform better academically (Baumrind, 1991). This style is often regarded as the most balanced and effective, fostering independence within a supportive environment.

Authoritarian Parenting

In contrast, authoritarian parenting exhibits low responsiveness and high demandingness. Parents adhering to this style impose strict rules and expect unwavering obedience, often resorting to punitive measures to enforce discipline. Communication is typically one-sided, with little consideration for the child’s input or emotional needs.

While this style may result in obedient and proficient children, it often leads to lower self-esteem, poor social skills, and heightened anxiety (Baumrind, 1967). In collectivist cultures, however, authoritarian parenting may align with cultural norms and yield positive outcomes, illustrating the influence of cultural context (Chao, 1994).

Permissive Parenting

Permissive parenting, defined by high responsiveness and low demandingness, is marked by indulgence and leniency. Parents prioritize their relationship with their children, often avoiding confrontation and enforcing few rules or boundaries.

While permissive parenting can create a warm and accepting environment, it may lead to challenges in self-regulation, poorer academic performance, and entitlement (Baumrind, 1991). Children in permissive households may struggle with authority and experience difficulties managing their behavior.

Neglectful/Uninvolved Parenting

Neglectful or uninvolved parenting combines low responsiveness with low demandingness. Parents using this style are disengaged, offering minimal guidance, support, or attention. This approach may stem from personal challenges, such as stress or mental health issues, which impede the parent’s ability to engage actively with their child.

Children raised in neglectful environments often experience poor academic and social outcomes, lower self-esteem, and behavioral and emotional problems (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). This style highlights the critical role of parental involvement in fostering healthy development.

Cultural and Contextual Considerations

Parenting styles are influenced by cultural norms and individual circumstances. For instance, authoritarian parenting may be more effective in collectivist cultures where obedience and family hierarchy are highly valued (Chao, 1994). Additionally, a parent’s style may evolve with time or vary between siblings based on factors such as the child’s temperament, environmental context, or life stressors.

In the years that have followed Ainsworth’s ground-breaking research, researchers have investigated various factors that may help determine whether children develop secure or insecure relationships with their primary attachment figures. As mentioned above, one of the key determinants of attachment patterns is the history of sensitive and responsive interactions between the caregiver and the child. In short, when the child is uncertain or stressed, the ability of the caregiver to provide support to the child is critical for his or her psychological development. It is assumed that such supportive interactions help the child learn to regulate his or her emotions, give the child the confidence to explore the environment, and provide the child with a safe haven during stressful circumstances.

Many longitudinal studies demonstrate prospective associations between early attachment experiences and adult attachment styles and/or interpersonal functioning in adulthood. For example, Fraley et al. (2013) found in a sample of more than 700 individuals studied from infancy to adulthood that maternal sensitivity across development prospectively predicted security at age 18.

Simpson et al. (2007) found that attachment security, assessed in infancy in the strange situation, predicted peer competence in grades 1 to 3, which, in turn, predicted the quality of friendship relationships at age 16, which, in turn, predicted the expression of positive and negative emotions in their adult romantic relationships at ages 20 to 23.

It is easy to come away from such findings with the mistaken assumption that early experiences “determine” later outcomes. Attachment theorists assume that the relationship between early experiences and subsequent outcomes is probabilistic, not deterministic. This means that having supportive and responsive experiences with caregivers early in life may set the stage for positive social development, but that doesn’t mean that attachment patterns are set in stone. Even if an individual has far from optimal caretaker experiences in early life, attachment theory suggests that that individual can develop well-functioning adult relationships through many corrective experiences, including relationships with siblings, other family members, teachers, and close friends.

Security is best viewed as a culmination of a person’s attachment history rather than a reflection of his or her early experiences alone. Those early experiences are important not because they determine a person’s fate but because they provide the foundation for later experiences.

It is essential to note that the attachment theory work of Bowlby and Ainsworth focused on Westernized caretaking ideals in determining healthy, secure attachment. As previously discussed, what is considered “ideal” in Westernized culture is not necessarily prioritized in other cultures. Sensitivity and caution is required in determining if observed attachment patterns are adaptive within the context of the child’s environment.

Peer and Sibling Relationships

Parent-child relationships are not the only significant relationships in a child’s life. Peer relationships are also meaningful. Social interaction with another child who is similar in age, skills, and knowledge provokes the development of many valuable social skills for the rest of life (Bukowski et al., 2011). In peer relationships, children learn how to initiate and maintain social interactions with other children. They learn skills for managing conflict, such as turn-taking, compromise, and bargaining. Play also involves the mutual, sometimes complex, coordination of goals, actions, and understanding. For example, as infants, children get their first encounter with sharing (of each other’s toys); during pretend play as preschoolers, they create narratives together, choose roles, and collaborate to act out their stories; and in primary school, they may join a sports team, learning to work together and support each other emotionally and strategically toward a common goal. Through these experiences, children develop friendships that provide additional sources of security and support to those offered by their parents.

Peer relationships are vital for children. They can be supportive but also challenging. Peer rejection may lead to behavioral problems later in life.

Sibling Dynamics: How Brothers and Sisters Affect Each Other (open YouTube video in new tab)

However, peer relationships can be challenging and supportive (Rubin et al., 2011). Being accepted by other children is an essential source of affirmation and self-esteem. Still, peer rejection can foreshadow later behavior problems (especially when children are rejected due to aggressive behavior). With increasing age, children confront the challenges of bullying, peer victimization, and managing conformity pressures. Social comparison with peers is a noteworthy means by which children evaluate their skills, knowledge, and personal qualities, but it may cause them to feel that they do not measure up well against others. For example, a boy who is not athletic may feel unworthy of his football-playing peers and revert to shy behavior, isolating himself and avoiding conversation. Conversely, athletes who don’t “get” Shakespeare may feel embarrassed and avoid reading altogether. Also, with the approach of adolescence, peer relationships become focused on psychological intimacy, involving personal disclosure, vulnerability, and loyalty (or its betrayal), significantly affecting a child’s outlook on the world. Each aspect of peer relationships requires developing very different social and emotional skills than those that emerge in parent-child relationships. They also illustrate how peer relationships influence the growth of personality and self-concept.

Education and Culture

Culture, education, and society are all interconnected concepts that work to enculturate a child. Education models are based on the ideals and principles of society, and then its educated citizens become influencers of that society’s culture. Researchers Markus and Kitayama (2010) refer to the systemic influence of culture and self as mutual constitution and point out that individuals are simultaneously being shaped by culture while also influencing it. Regardless of the method of education, schooling serves as both a reflection of the priorities and values of that society while also enculturating its young to contribute to that culture. For example, core American values of competition, choice, and independence can be seen in how we structure our formal education system. Parents and students often expect to play a role in choosing curriculum and classes, and competition for academic and athletic status is expected within schools. Similarly, in the United States, the government dictates larger educational goals and resources, while state and local districts pass mandates based on the democratic wishes of the larger society. In contrast to Westernized education systems, many East Asian education models are based on uniform standards of academic rigor, student conformity, and respect for authority.

How can the lack of social contact and appropriate environmental stimuli affect the individual? In this lesson, we have learned that parents and caregivers are the primary enculturation agents, that genetics and environment (nature and nurture) are influential in all human development, and that a child’s social network is also vital to the individual’s development. The implications related to deprivation of regular human contact and social interaction can have far-reaching and life-long effects.

Key Takeaways

There are many theories regarding how babies and children grow and develop into happy, healthy adults. Sigmund Freud suggested that we pass through a series of psychosexual stages in which our energy is focused on certain erogenous zones of the body. Eric Erikson modified Freud’s ideas and suggested a theory of psychosocial development. Erikson said that social interactions and successful completion of social tasks shape our sense of self. Jean Piaget proposed a theory of cognitive development that explains how children think and reason as they move through various stages. Finally, Lawrence Kohlberg turned his attention to moral development. He said that we pass through three levels of moral thinking that build on our cognitive development.

The process of enculturation is complex and culture-specific. Our caretakers and schooling method are two of childhood’s most essential enculturation agents. Differences in child-rearing choices, traditions, and expectations reflect differences in values and priorities. It is crucial to view child-raising decisions through a cultural context lens to avoid making ethnocentric evaluations. It is essential to recognize that what is “ideal” in some contexts and cultures may not be ideal in another context or a different culture.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- pexels-william-fortunato-6392925 © William Fortunato is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- family-320654_1280 © kim881231 is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- original © Noba project is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Uninvolved © P. Crossman is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license