5.1 Sensation and Perception

Cognition is involved in everything we do, experience, and believe. Learning, processing information, and reacting to the world requires cognition and cognitive processes. The way an individual is raised and the beliefs, values, and morals instilled in him or her may change over time, and this is due to cognitive processes that evolve throughout our lifetime. Until this point in the course, we’ve briefly covered the work of Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development. This chapter will delve further into the concept of cognition, the cognitive processes of the brain, and how cognition affects behavior.

We will learn that the brain is central to sensing and perceiving our world, but culture is at the heart of thinking. Culture shapes how we perceive information, evaluate the information, and use the information in our daily lives. We organize the world into networks of information that are stored and used to interpret new experiences. This knowledge can be represented into hierarchical concepts with superordinate, basic, and subordinate categories. We hold information in short-term memory and process it using networks of information in long-term memory, some from episodic experiences and some from more formal semantic knowledge. Intelligence is among the oldest and longest-studied topics in all of psychology. The development of assessments to measure this concept is at the core of the development of psychological science itself. The way we perceive, remember, and think about the world we live in is influenced by our culture.

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between sensation, attention, and perception in describing how humans use these to derive meaning.

- Summarize how humans use attention to filter information from sensation into perception.

- Describe how culture influences our perception and attention.

- Describe the theories of intelligence and cross-cultural differences related to the cognitive process of intelligence.

Sensation and Perception

“What we see changes what we know. What we know changes what we see.” Jean Piaget

Cognition and Culture

Cognition has been discussed throughout the course, as it plays a central role in how individuals are formed by their culture; in turn, they form and transform their culture. We represent the world using cognitive processes. The keyword, representation, implies that the world is first presented to us, and we then organize the information into new or already existing representations or schemas. We never experience the world outside of our brain in a perfect, objective, or pure way. Instead, our representation of the world relies on subjective and imperfect processes, including sensation, perception, attention, memory, thinking, judging, and problem-solving. We will cover many of these concepts in this lesson.

Sensation and Perception Mental Processes

Sensation and perception are two separate yet closely related processes. Sensation is input about the physical world obtained by our sensory receptors. Perception is how the brain selects, organizes, and interprets these sensations. Sensation and perception are among the oldest and most important in all psychology. People are equipped with senses such as sight, hearing, and taste, which help us to take in the world around us. Amazingly, our senses can convert real-world information into electrical information that the brain can process. How we interpret this information—our perceptions—leads to our experiences of the world. In this module, you will learn about the biological processes of sensation and how these can be combined to create perceptions.

Sensation

Sensation is the process of receiving information or stimulation (stimuli) from the environment and the initial encoding of that stimulation into our nervous system. In other words, sensation is the physiological processing of external stimuli on our senses (sight, sound, taste, smell, touch). What does it mean to sense something? Sensory receptors are specialized neurons that respond to specific types of stimuli. When a sensory receptor detects sensory information, the sensation occurs. For example, light that enters the eye causes chemical changes in cells that line the back of the eye. These cells relay messages as action potentials to the central nervous system. An action potential occurs when a neuron sends information down an axon away from the cell body. The conversion from sensory stimulus energy to action potential is known as transduction.

You have probably known since elementary school that we have five senses:

- vision

(optics) - hearing

(audition) - smell

(olfaction) - taste

(gustation) - touch

(somatosensation)

It turns out that this notion of the five senses is oversimplified.

We also have sensory systems that provide information about:

- balance

(vestibular) - body position

(proprioceptive) - movement

(kinesthetic) - pain

(nociception) - temperature

(thermoception)

The sensitivity of a given sensory system to the relevant stimuli can be expressed as an absolute threshold. Absolute threshold refers to the minimum amount of stimulus energy that must be present for the stimulus to be detected 50% of the time. Another way to think about this is by asking how dim a light can be or how soft a sound can be and still be detected half the time. The sensitivity of our sensory receptors can be pretty remarkable. It has been estimated that on a clear night, the most sensitive sensory cells in the back of the eye can detect a candle flame 30 miles away (Okawa & Sampath, 2007). Under quiet conditions, the hair cells (the receptor cells of the inner ear) can detect the tick of a clock 20 feet away (Galanter, 1962).

It is also possible for us to get messages that are presented below the absolute threshold for conscious awareness—these are called subliminal messages. A stimulus reaches a physiological threshold when it is strong enough to excite sensory receptors and send nerve impulses to the brain. This is an absolute threshold. A message below that threshold is said to be subliminal: We receive it but are not consciously aware of it. Over the years, there has been much speculation about the use of subliminal messages in advertising, rock music, and self-help audio programs. Research shows that in laboratory settings, people can process and respond to information outside of awareness. But this does not mean that we obey these messages like zombies; in fact, hidden messages have little effect on behavior outside the laboratory (Kunst-Wilson & Zajonc, 1980; Rensink, 2004; Nelson, 2008; Radel et al., 2009; Loersch et al., 2013).

Absolute thresholds are generally measured under incredibly controlled conditions in situations optimal for sensitivity. Sometimes, we are more interested in how much difference in stimuli is required to detect a difference between them. This is the just noticeable difference (JND) or difference threshold. Unlike the absolute threshold, the difference threshold changes depending on the stimulus intensity. As an example, imagine yourself in a very dark movie theater. If an audience member received a text message on her cell phone that caused her screen to light up, chances are that many people would notice the change in illumination in the theater. However, very few people would notice if the same thing happened in a brightly lit arena during a basketball game. The cell phone brightness does not change, but its ability to be detected as a change in illumination varies dramatically between the two contexts.

The Sensory System (open YouTube video in new tab)

Perception

While our sensory receptors are constantly collecting information from the environment, how we interpret that information affects how we interact with the world. Perception refers to how sensory information is organized, analyzed, and consciously experienced. Perception involves both bottom-up and top-down processing. Bottom-up processing refers to the fact that perceptions are built from sensory input. On the other hand, how we interpret those sensations is influenced by our available knowledge, our experiences, and our thoughts. This is called top-down processing.

One way to think of this concept is that sensation is a physical process, whereas perception is psychological. For example, upon walking into a kitchen and smelling the scent of baking cinnamon rolls, the sensation is the scent receptors detecting the odor of cinnamon. Still, the perception may be, “Mmm, this smells like the bread Grandma used to bake when the family gathered for holidays.”

Although our perceptions are built from sensations, not all sensations result in perception. We often don’t perceive stimuli that remain relatively constant over prolonged periods, known as sensory adaptation. Imagine entering a classroom with an old analog clock. Upon first entering the room, you can hear the clock ticking; as you begin conversing with classmates or listening to your professor greet the class, you are no longer aware of the ticking. The clock is still ticking, and that information still affects sensory receptors of the auditory system. The fact that you no longer perceive the sound demonstrates sensory adaptation and shows that sensation and perception are different, while closely associated.

Sensation & Perception: Top-Down & Bottom-Up Processing (open YouTube video in new tab)

Check your understanding of Sensation vs. Perception

How Culture Influences What We Perceive

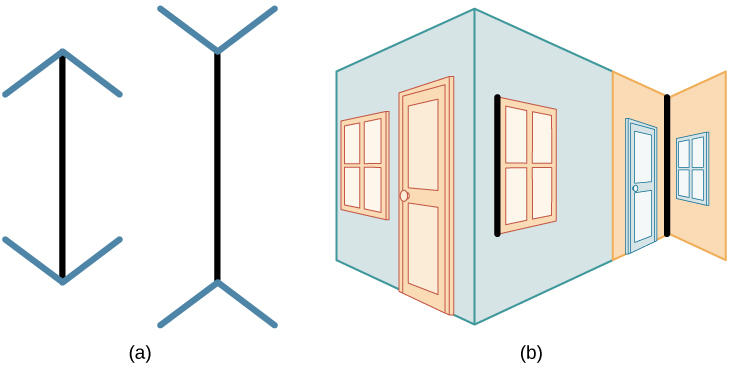

Our beliefs, values, prejudices, expectations, and life experiences can also affect our perceptions. The shared experiences of people within a given cultural context can have pronounced effects on perception. For example, Segall et al. (1963) published the results of a multinational study in which they demonstrated that individuals from Western cultures were more prone to experience certain types of visual illusions than individuals from non-Western cultures, and vice versa. One such illusion that Westerners were more likely to experience was the Müller-Lyer illusion (below): The lines appear to be different lengths but are actually the same length.

Although both lines are the same length, they appear different in this illusion.

(a) Arrows at the ends of lines make the line on the right appear longer.

(b) When applied to a three-dimensional image, the line on the right appears longer.

These perceptual differences were consistent with differences in the types of environmental features experienced regularly by people in a given cultural context. People in Western cultures, for example, have a perceptual context of buildings with straight lines, which Segall’s study called a carpentered world (Segall et al., 1966). In contrast, people from certain non-Western cultures with an uncarpentered view, such as the Zulu of South Africa, whose villages are made up of round huts arranged in circles, are less susceptible to this illusion (Segall et al., 1999). It is not just vision that is affected by cultural factors. Indeed, research has demonstrated that the ability to identify an odor and rate its pleasantness and intensity varies cross-culturally (Ayabe-Kanamura et al., 1998).

Children described as thrill seekers are likelier to show taste preferences for intense sour flavors (Liem et al., 2004), suggesting that fundamental aspects of personality might affect perception. Furthermore, individuals with positive attitudes toward reduced-fat foods are more likely to rate foods labeled as reduced-fat as tasting better than those with less positive attitudes about these products (Aaron et al., 1994).

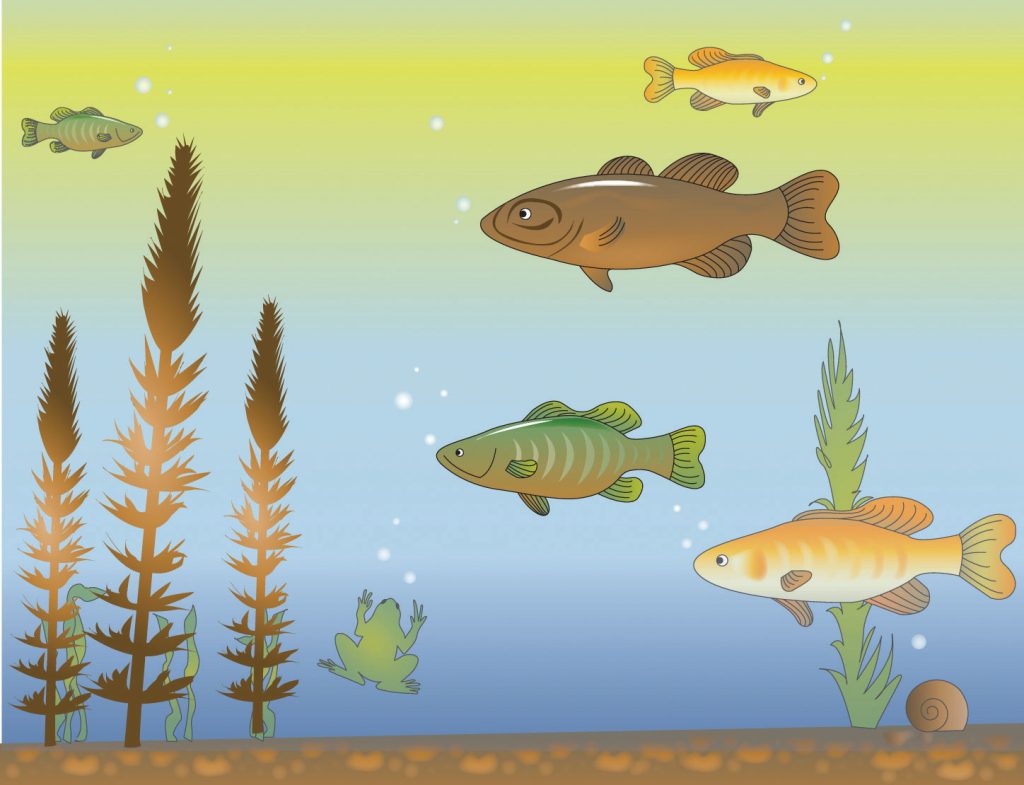

Culture can also influence and shape how we attend to the world around us. Masuda and Nisbett (2001) asked American and Japanese students to describe what they saw in images like the one below. They found that while both groups talked about the most salient objects (the fish, which were brightly colored and swimming around), the Japanese students also tended to speak and remember more about the images in the background (they remembered the frog and the plants as well as the fish).

In these types of studies, North Americans and Western Europeans were more likely to pay attention to salient and central parts of the pictures, while Japanese, Chinese, and South Koreans were more likely to consider the context as a whole.

Categorization of Concepts

The way concepts are formed can vary significantly across cultures. For example, Western cultures often emphasize analytical thinking, focusing on individual objects and their attributes. In contrast, East Asian cultures tend to use holistic thinking, considering the context and relationships between objects. This difference affects how categories are created and understood. Researchers described this as holistic perception and analytic perception.

Holistic Perception: A pattern or perception characterized by processing information as a whole.

This pattern makes it more likely to pay attention to relationships among all elements. Holistic perception promotes holistic cognition: a tendency to understand the gist, the big idea, or the general meaning. Eastern medicine is traditionally holistic; it emphasizes health in general terms as the result of the connection and balance between mind, body, and spirit.

Analytic Perception: A pattern of perception characterized by processing information as a sum of the parts.

Analytic perception promotes analytic thinking, a tendency to understand the parts and details of a system. This pattern makes it more likely to pay attention and remember salient, central, and individual elements. Western medicine is traditionally analytic; it emphasizes specialized subdisciplines, and it focuses on particular symptoms and body parts.

How we attend to and perceive our world has implications for how we evaluate and explain the world around us, including the actions of others. In summary, sensation occurs when sensory receptors detect sensory stimuli. Perception involves the organization, interpretation, and conscious experience of those sensations. All sensory systems have both absolute and difference thresholds, which refer to the minimum amount of stimulus energy or the minimum amount of difference in stimulus energy required to be detected about 50% of the time, respectively. Sensory adaptation, selective attention, and signal detection theory can help explain what is perceived and what is not. In addition, our perceptions are affected by several factors, including beliefs, values, prejudices, culture, and life experiences.

In summary, the brain is central to sensing and perceiving our world, but culture shapes how we perceive information, evaluate the information, and use the information in our daily lives.

Categories

The information we sense and perceive is continuously organized and reorganized into concepts that belong to categories. Most concepts cannot be strictly defined but are organized around the best examples or prototypes, which have the properties most common in the category or might be considered the ideal example of a category. Different cultures may have different prototypes for the same category. For instance, a “bird” prototype in one culture might be a sparrow, while in another, it might be a parrot. These prototypes shape how people in different cultures perceive and categorize their world.

Concepts are abstract ideas or general notions that occur in the mind, speech, or thought. Concepts are at the core of intelligent behavior. We expect people to be able to know what to do in new situations and when confronted with new objects. If you enter a new classroom and see chairs, a blackboard, a projector, and a screen, you know what these things are and how they will be used. You’ll sit on one of the chairs and expect the instructor to write on the blackboard or project something onto the screen. You’ll do this even if you have never seen any of these objects before because you have concepts of classrooms, chairs, projectors, and so forth that tell you what they are and what you’re supposed to do with them. Objects fall into many different categories, but there is usually a hierarchy to help us organize our mental representations.

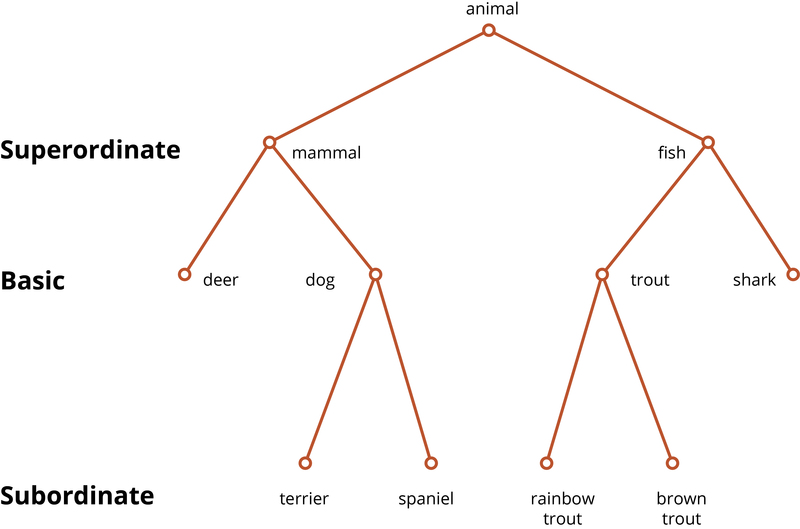

- A concept at the superordinate level of categories is at the top of a taxonomy, and it has a high degree of generality (e.g., animal, fruit).

- A concept at the basic level categories is found at the generic level which contains the most salient differences (e.g., dog, apple).

- A concept at the subordinate level of categories is a specific degree and has little generality (e.g., Labrador retriever, Gala).

The hierarchical structure of categories (superordinate, basic, subordinate) can also be influenced by cultural factors. For example, the basic level category might differ between cultures based on what is most commonly encountered or most significant in daily life. In some cultures, the basic level for fruit might be “apple,” while in others, it might be “mango.” Social and cultural norms play a crucial role in shaping concepts and categories. These norms dictate what is considered important or relevant within a culture, influencing the formation and use of concepts. For example, the concept of “family” can vary widely between cultures, affecting how family members are categorized and perceived. Understanding these cultural influences is essential for appreciating the diversity in human cognition and behavior. It highlights the importance of considering cultural context in psychological research and practice.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- markus-spiske-ipYwpFUwC-I-unsplash © Markus Spiske is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- pexels-yankrukov-7695391 © Yan Krukau is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- CNX_Psych_05_01_MullerLyer8 is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- 6c3ce111c477677570ae12c5c8230554 © Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani and Dr. Hammond Tarry is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Hierarchal Levels © Gregory Murphy adapted by The Noba Project is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license