5.3 Intelligence as a Cognitive Process

Thinking and Intelligence

The way we represent the world influences the degree of success we experience in our lives. For example, if we represent yellow traffic lights as the time to hit the accelerator, the world might give us tickets, scares, or accidents. If we represent our diet as a way to maximize refined sugar intake, then we might wind up experiencing heart disease. Mental representations and intelligence go hand in hand. Some mental representations are more intelligent because they are more adaptive and support outcomes such as well-being, safety, and success. In this section, we will cover other elements of thinking, like categorization, memory, and intelligence, and how culture shapes these processes.

Intelligence as a Cognitive Process

Psychologists have long debated how to best conceptualize and measure intelligence (Sternberg, 2003). These questions include how many types of intelligence there are, the role of nature vs. nurture on intelligence, how intelligence is represented in the brain, and the meaning of group differences in intelligence. The concept of intelligence relates to abstract thinking, which includes our abilities to acquire knowledge, reason abstractly, adapt to novel situations, and benefit from instruction and experience (Gottfredson, 1997; Sternberg, 2003). The brain processes underlying intelligence are not fully understood, but current research has focused on four potential factors:

- Brain size

- Sensory ability

- Speed and efficiency of neural transmission

- Working memory capacity

There is some truth to the idea that more intelligent people have bigger brains. Studies that have measured brain volume using neuroimaging techniques find that larger brain size is correlated with intelligence (McDaniel, 2005).

Intelligence has also been correlated with the number of neurons in the brain and the thickness of the cortex (Haier, 2004; Shaw et al., 2006).

It is important to remember that these correlational findings do not mean that having more brain volume causes higher intelligence. It is possible that growing up in a stimulating environment that rewards thinking and learning may lead to more significant brain growth (Garlick, 2003), and it is also possible that a third variable, such as better nutrition, causes both brain volume and intelligence.

There is some evidence that the brains of more intelligent people operate more efficiently than the brains of people with less intelligence. Haier et al. (1992) analyzed data showing that more intelligent people showed less brain activity than those with lower intelligence when they worked on a task. Researchers suggested that more intelligent brains need to use less capacity. Brains of more intelligent people also seem to operate faster than the brains of those who are less intelligent. Research has found that the speed with which people can perform simple tasks, like determining which of two lines is longer or quickly pressing one of eight lighted buttons, was predictive of intelligence (Deary et al., 2001). Intelligence scores also correlate with measures of working memory (Ackerman et al., 2005), and working memory is now used to measure intelligence on many tests.

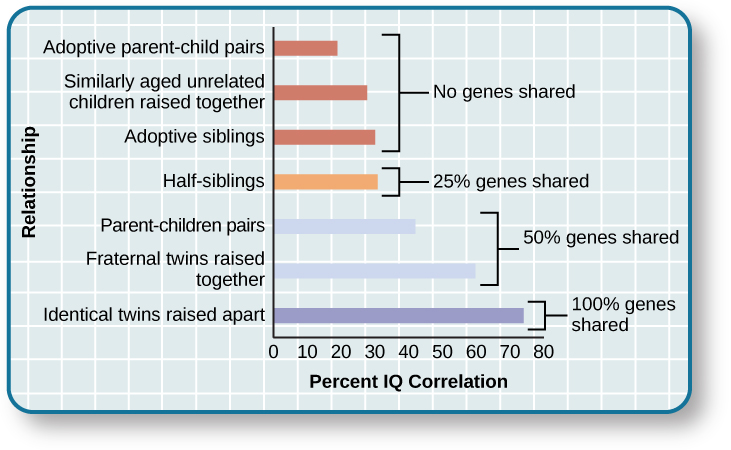

The correlations of intelligence scores of unrelated versus related persons raised apart or together suggest a genetic component to intelligence.

Research using twin and adoption studies found that intelligence has genetic and environmental causes (Neisser et al., 1996; Plomin et al., 2003). It appears that 40%-80% of the variability (difference) in intelligence is due to genetics (Plomin & Spinath, 2004). The intelligence of identical twins correlates very highly, much higher than the scores of fraternal twins, who are less genetically similar. The correlation between parents’ intelligence and their biological children is significantly higher than between parents and adopted children. The intelligence of very young children (less than 3 years old) does not predict adult intelligence. Still, by age 7, intelligence scores (as measured by a standard test) remain very stable in adulthood (Deary et al., 2004).

There is also strong evidence for the role of nurture, which indicates that individuals are not born with fixed, unchangeable levels of intelligence. Twins raised together in the same home have more similar intelligence scores than twins raised in different homes, and fraternal twins have more similar intelligence scores than non-twin siblings, which is likely since they are treated more similarly than siblings. Additionally, intelligence becomes more stable as we age, proving that early environmental experiences matter more than later ones.

Environmental factors also explain a more significant proportion of the variance in intelligence, and social and economic deprivation can adversely affect intelligence. Children from impoverished households have lower intelligence scores than those with more resources, even when factors such as education, race, and parenting are controlled (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997). Poverty may contribute to diets that undernourish the brain or lack appropriate vitamins. Poor children are more likely to be exposed to toxins such as lead in drinking water, dust, or paint chips (Bellinger & Needleman, 2003). Both of these factors can slow brain development and reduce intelligence.

Intelligence is improved by education and the number of years a person has spent in school (Ceci, 1991). There is a word of caution when interpreting this result. The correlation may be because people with higher intelligence scores enjoy taking classes more than people with lower intelligence scores and may be more likely to stay in school. Children’s intelligence scores tend to drop significantly during summer vacations (Huttenlocher et al., 1998), a finding that suggests a causal effect on intelligence and education. A more extended school year, as is used in Europe and East Asia, may be beneficial for maintaining intelligence scores for school-aged children.

Important Considerations Regarding Culture

It is important to note that the research findings on intelligence covered thus far are based mainly on standardized tests. According to some researchers, intelligence or IQ tests ignore culturally specific considerations, making the tests biased toward the environments in which they were developed, namely, white, Western societies. This makes them potentially problematic in culturally diverse settings.

Controversy of Intelligence: Crash Course (open YouTube video in new tab)

Theories of Intelligence

The G Factor

Intelligence is associated with the brain, includes abstract thinking, adapting to new situations, and the ability to benefit from instruction and experience (Gottfredson, 1997; Sternberg, 2003), and is primarily determined by genetics. Psychologist Charles Spearman (1863–1945) hypothesized that a single underlying construct must link these concepts, abilities, and skills. He called this construct the general intelligence factor (g), and there is strong empirical support for a single dimension of intelligence.

Other psychologists believe intelligence is a collection of distinct abilities instead of a single factor. Raymond Cattell proposed a theory of intelligence that divided general intelligence into crystallized and fluid intelligence (Cattell, 1963).

- Crystallized intelligence is characterized as acquired knowledge and the ability to retrieve it. When you learn, remember, and recall information, you use crystallized intelligence. You use crystallized intelligence all the time in your coursework by demonstrating that you have mastered the information covered in the course.

- Fluid intelligence encompasses the ability to see complex relationships and solve problems. Navigating your way home after being detoured onto an unfamiliar route because of road construction would draw upon your fluid intelligence. Fluid intelligence helps you tackle complex, abstract challenges daily, whereas crystallized intelligence helps you overcome concrete, straightforward problems (Cattell, 1963).

Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence (open YouTube video in new tab)

Other theorists and psychologists believe intelligence should be defined more practically. For example, what types of behaviors help you get ahead in life? Which skills promote success? Think about this for a moment. Being able to recite all 45 presidents of the United States in order is an excellent party trick, but will knowing this make you a better person?

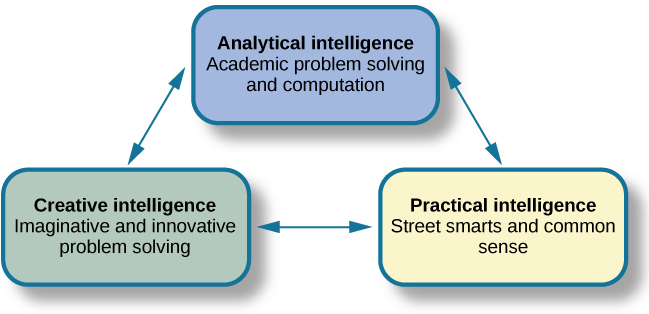

Robert Sternberg developed another theory of intelligence, the triarchic theory of intelligence. He proposed that intelligence consists of three parts (Sternberg, 1988): creative, analytical, and practical intelligence (CAP).

- Creative intelligence is marked by inventing or imagining a solution to a problem or situation. Creativity in this realm can include finding a novel solution to an unexpected problem or producing a beautiful work of art or a well-developed short story.

- Analytical intelligence is closely aligned with academic problem-solving and computations. Sternberg says that analytical intelligence is demonstrated by an ability to analyze, evaluate, judge, compare, and contrast. For example, in a science course such as anatomy, you must study how the body uses various minerals in different human systems. In developing an understanding of this topic, you are using analytical intelligence.

- Practical intelligence is sometimes compared to “street smarts.” Being practical means you find solutions that work in your everyday life by applying knowledge based on your experiences.

Diagram: Sternberg’s theory identifies three types of intelligence: practical, creative, and analytical.

Multiple Intelligences Theory

Multiple Intelligences Theory was developed by Howard Gardner, a Harvard psychologist and former student of Erik Erikson. Gardner’s theory, which has been refined for more than 30 years, is a more recent development among theories of intelligence. In Gardner’s theory, each person possesses at least eight intelligences. Among these eight intelligences, a person typically excels in some and falters in others (Gardner, 1983). The following table describes each type of intelligence.

| Intelligence Type | Characteristics | Representative Career |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistic intelligence | Perceives different functions of language, various sounds, and meanings of words, and may easily learn multiple languages | Journalist, novelist, poet, teacher |

| Logical-mathematical intelligence | Capable of seeing numerical patterns, strong ability to use reason and logic | Scientist, mathematician |

| Musical intelligence | Understands and appreciates rhythm, pitch, and tone; may play multiple instruments or perform as a vocalist | Composer, performer |

| Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence | High ability to control the movements of the body and use the body to perform various physical tasks | Dancer, athlete, athletic coach, yoga instructor |

| Spatial intelligence | Ability to perceive the relationship between objects and how they move in space | Choreographer, sculptor, architect, aviator, sailor |

| Interpersonal intelligence | Ability to understand and be sensitive to the various emotional states of others | Counselor, social worker, salesperson |

| Intrapersonal intelligence | Ability to access personal feelings and motivations and use them to direct behavior and reach personal goals | Key component of personal success over time |

| Naturalist intelligence | High capacity to appreciate the natural world and interact with the species within it | Biologist, ecologist, environmentalist |

Gardner’s theory is relatively new and needs additional research to establish empirical support better. At the same time, his ideas challenge the traditional concept of intelligence to include a wider variety of abilities. However, it has been suggested that Gardner relabeled what other theorists called “cognitive styles” as “intelligences” (Morgan, 1996). Furthermore, developing traditional measures of Gardner’s intelligences is extremely difficult (Furnham, 2009; Gardner & Moran, 2006; Klein, 1997).

Emotional Intelligence

Gardner’s inter- and intrapersonal intelligences are often combined into one type: emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence encompasses understanding the emotions of yourself and others, showing empathy, understanding social relationships and cues, regulating emotions, and responding in culturally appropriate ways (Parker et al., 2009). People with high emotional intelligence typically have well-developed social skills. Some researchers, including Daniel Goleman, the author of Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ, argue that emotional intelligence is a better predictor of success than traditional intelligence (Goleman, 1995). However, emotional intelligence has been widely debated, with researchers pointing out inconsistencies in how it is defined and described and questioning the results of studies on a subject that is difficult to measure and study empirically (Locke, 2005; Mayer et al., 2004).

Check your understanding of the different theories of intelligence

Intelligence and Culture

Intelligence can also have different meanings and values in other cultures. If you live on a small island, where most people get their food by fishing from boats, knowing how to fish and repair a boat would be essential. If you were an exceptional angler, your peers would consider you intelligent. If you were also skilled at repairing boats, your intelligence might be known across the island. Think about your own family’s culture. What values are important for Latino families? Italian families? In Irish families, hospitality and telling an entertaining story are marks of the culture. If you are a skilled storyteller, other members of Irish culture are likely to consider you intelligent.

Some cultures place a high value on working together as a collective. In these cultures, the importance of the group supersedes the importance of individual achievement. When you visit such a culture, how well you relate to the values of that culture exemplifies your cultural intelligence, sometimes referred to as cultural competence.

The Social Brain and Its Superpowers (open YouTube video in new tab)

Culture and Categorization

Some universal categories include emotions, facial expressions, shape, and color, but culture can shape how we organize information. Chiu (1972) was the first to examine cultural differences in categorization using Chinese and American children. Participants were presented with three pictures (e.g., a tire, a car, and a bus) and were asked to group the two pictures they thought best belonged together. Participants were also asked to explain their choices (e.g., “Because they are both large”). Results showed that Chinese children tend to categorize by identifying relationships among pictures, but American children were more likely to categorize by identifying similarities among pictures.

Later research reported no cultural differences in categorization between Western and East Asian participants; however, among similarity categorizations, the East Asian participants were more likely to make decisions on holistic aspects of the images, and Western participants were more likely to make decisions based on individual components of the photos (Norenzayan et al., 2002). Unsworth, Sears, and Pexman (2005) also found cultural differences in categorizing across three experiments. However, when the experiment task was timed, there were differences in category selection. These results suggest that the nature (timed or untimed) of the categorization task determines the extent to which cultural differences are observed.

The results of these categorization studies support the differences in thinking between individualist and collectivist cultures. Western cultures are more individualist and engage in more analytic thinking, and East Asian cultures engage in more holistic thinking (Choi, Nisbett, & Smith, 1997; Masuda & Nisbett, 2001; Nisbett et al., 2001; Peng & Nisbett, 1999). You might remember from the earlier section that holistic thought is characterized by a focus on context and environmental factors, so categorizing by relationships can be explained by referencing how objects relate to their environment. Analytic thought is characterized by separating an object from its context, so categorizing by similarity means that objects can be divided into different groups. A major limitation of these studies is the emphasis on East Asia, specifically the use of Chinese participants and Western cultures. There have been no replications using participants from other non-Asian collectivist cultures.

Key Takeaways

Earlier in the lesson, we learned that the brain is central to sensing and perceiving our world, but culture is at the heart of thinking. Culture shapes how we perceive information, evaluate information, and use the information in our daily lives. We organize the world into networks of information that are stored and used to interpret new experiences. This knowledge can be represented in hierarchical concepts with superordinate, basic, and subordinate categories. We hold information in short-term memory and process it using networks of information in long-term memory, some from episodic experiences and some from more formal semantic knowledge. Intelligence is among the oldest and longest-studied topics in all of psychology. The development of assessments to measure this concept is at the core of the development of psychological science itself. The way we perceive, remember, and think about the world we live in is influenced by our culture.

Media Attributions

- pexels-cottonbro-4691560-1 © cottonbro studio is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Neural_signaling-human_brain is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 001071e67e7f0cc757471bf4acbfee65296eb206 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- CNX_Psych_07_04_Triachic1 © OpenStax is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license