6.3 Sexuality and Sexual Orientation

Sex and gender are essential aspects of a person’s identity; however, they do not tell us about a person’s sexual orientation or sexuality (Rule & Ambady, 2008). Sexuality refers to the way people experience and express sexual feelings. Sexual attraction is part of human sexuality, and sexual orientation refers to enduring patterns of sexual attraction and is typically divided into four categories:

- heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the opposite sex;

- homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of one’s own sex;

- bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; and

- asexuality, no attraction to either sex.

Heterosexuals and homosexuals are informally referred to as “straight” and “gay,” respectively. North America is a heteronormative society, meaning it supports heterosexuality as the norm. While the majority of people identify as heterosexual, there is a sizable population of people in North America who identify as either homosexual or bisexual. According to the Williams Institute at UCLA, around 3.5% of Americans identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual; this means there are around 9 million LGBT people in the United States. It is widely accepted and determined that one’s sexual orientation is not a choice, but rather, it is a relatively stable characteristic of a person that cannot be changed.

Research has consistently demonstrated that there are no differences in the family backgrounds and experiences of heterosexuals and homosexuals (Bell et al., 1981; Ross & Arrindell, 1988). Genetic and biological mechanisms have also been proposed, and the balance of evidence suggests that sexual orientation has an underlying biological component. Over the past 25 years, research has identified genetics (Bailey & Pillard, 1991; Hamer et al., 1993; Rodriguez-Larralde & Paradisi, 2009) and brain structure and function (Allen & Gorski, 1992; Byne et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2008; LeVay, 1991; Ponseti et al., 2006; Rahman & Wilson, 2003a; Swaab & Hofman, 1990; Swaab, 2008) as biological explanations for sexual orientation.

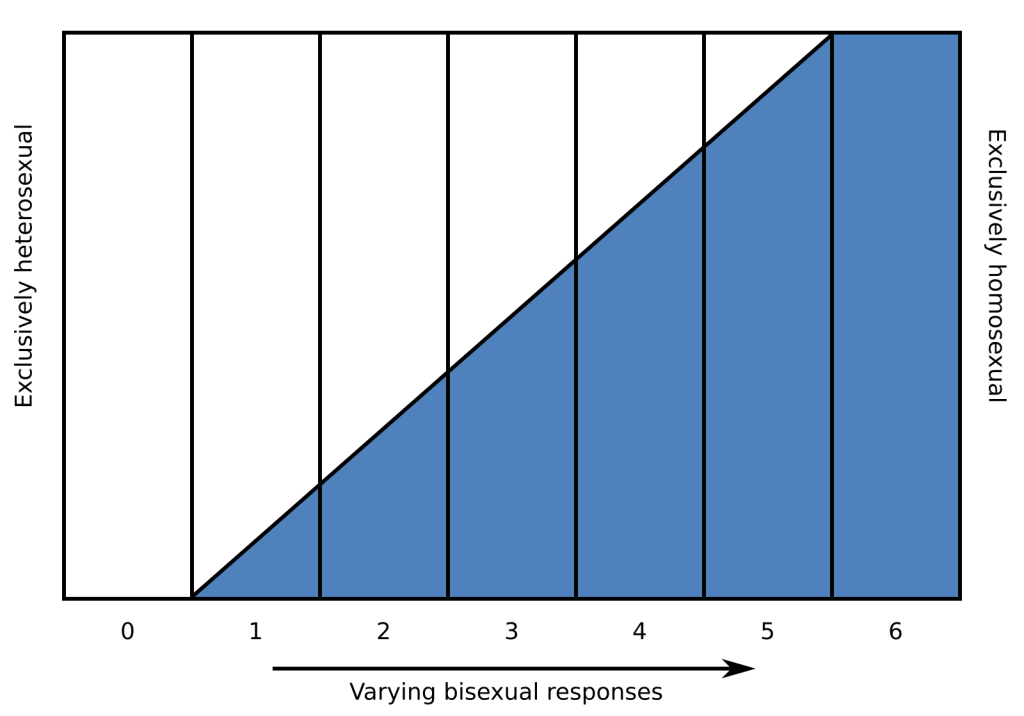

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association, 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual.

Cultural Influences on Sexuality

Three major cultural and social factors influence views on gender and sexuality:

- laws

- religion

- social norms

Let’s take a look at each factor separately.

Laws

Legal Protections and Rights: Laws can protect or restrict the rights of individuals based on gender and sexuality, such as marriage equality, adoption rights, anti-discrimination protections, or legal recognition of gender identity.

- Example: In the U.S., Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) legalized same-sex marriage nationwide.

- In Iceland, a pioneering Equal Pay Certification law requires companies to prove that they pay men and women equally for the same work.

- In Japan, despite laws promoting gender equality, women often face indirect discrimination, such as being overlooked for promotions due to cultural assumptions about their family roles.

Criminalization: In some countries, laws criminalize same-sex relationships or non-conforming gender identities.

- Example: As of 2025, over 60 countries still criminalize same-sex relationships.

Gender-based Legal Requirements: Some laws enforce traditional gender roles, such as requiring men to be primary breadwinners or restricting women’s participation in certain professions.

- Example: Saudi Arabia’s guardianship laws previously limited women’s rights to travel and work without male accompaniment and consent (reformed in 2019).

- On average, women earn about 77 cents for every dollar earned by men globally, according to the World Economic Forum (2022).

Religion

Moral Teachings: Religious doctrines often provide guidelines on acceptable gender roles and sexual behaviors.

- Example: Many Christian denominations oppose same-sex marriage based on biblical teachings.

- In Islam, traditional interpretations of the Quran emphasize distinct roles for men and women, such as men being providers and women as caregivers.

Cultural Variations in Religious Interpretations: The same religion can have different interpretations depending on the cultural context, leading to varying stances on gender and sexuality.

- Example: Hindu texts have historically recognized non-binary identities, but modern Hindu societies vary in their acceptance of LGBTQ+ rights.

- In Judaism, Orthodox traditions often separate roles along gender lines, with men primarily leading religious rituals, while Conservative and Reform Judaism practice gender neutrality, including the ordination of female rabbis.

Religious Influence on Policy: In some nations, religion directly influences laws and policies related to gender and sexuality.

- Example: Iran’s Islamic laws:

- Dress Code Enforcement: Women are legally mandated to wear hijabs and loose-fitting clothing to maintain modesty, while men face far fewer restrictions regarding attire. Failure to adhere to these laws can result in fines, imprisonment, or public chastisement for women. In contrast, violations by men, such as wearing shorts in public, generally draw less severe consequences.

- Legal Testimony and Inheritance Rights: A woman’s testimony in court is legally considered to hold half the weight of a man’s. Similarly, inheritance laws often allocate a smaller share to daughters and widows compared to sons and husbands, perpetuating gender disparities in wealth accumulation and financial independence.

- Freedom of Movement: Women require the permission of a male guardian, such as a father or husband, for certain actions, including travel. This restriction on autonomy does not apply to men.

Norms

Cultural Expectations: Societal norms shape what is considered acceptable behavior for men and women, as well as for individuals outside the gender binary.

- Example: In many cultures, women are expected to care for children, the elderly, and household responsibilities. For instance, in Japan, women are often called the “kyoiku mama,” or “education mothers,” responsible for their children’s academic success. Men, however, are seldom held to these expectations.

- Women in caregiving roles often face the “motherhood penalty” in hiring and promotion decisions, with employers perceiving them as less committed to their jobs. Conversely, men who take on caregiving roles may experience a “fatherhood bonus,” rewarding them for being considered responsible providers.

- In Sweden, while generous parental leave policies exist for both men and women, men still use significantly less of the leave due to societal expectations of them maintaining their roles as primary earners.

Media Representation: Media often reflect and reinforce societal norms, shaping public perceptions of gender and sexuality.

- Example: Television commercials and shows frequently depict women in domestic roles, such as cooking or cleaning, while portraying men as business professionals or leaders, perpetuating traditional gender stereotypes.

Generational Shifts: Younger generations often challenge traditional norms and push for greater acceptance of diverse gender identities and sexual orientations.

- Example: Gen Z individuals in many Western countries are significantly more likely to identify as LGBTQ+ compared to previous generations.

These disparities underscore how legal frameworks, rooted in specific interpretations of religious doctrine, can institutionalize gender inequalities, shaping the everyday experiences of men and women in distinct ways.

In the United States and other Western countries, cisgender women have greater legal protections than in other parts of the world. Globally, inequality is still enforced through laws in many parts of the world. For example, laws and policies prohibit women from equal access and ownership of land, property, and housing. Economic and social discrimination result in fewer life choices for women, rendering them vulnerable to poverty and human trafficking. Gender-based violence affects at least 30% of women globally. Some women who are victims of violence often have few legal protections or have limited legal recourse (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner, 2018). For example, in some cultures, a woman may not be able to have her attacker arrested or prosecuted.

Within the United States, there has been greater acceptance of homosexuality and gender questioning that has resulted in a rapid push for legal change. Laws such as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), both of which were enacted in the 1990s, have met severe resistance and legal challenges on the grounds of being discriminatory toward sexual minority groups. Globally, a significant number of governments have recognized and legalized same-sex marriages. As of 2017, over 24 countries have enacted national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry. These laws have primarily been enacted and enforced in Europe and North America. In Mexico, some jurisdictions allow same-sex couples to wed, while others do not (Pew, 2013).

Gender stereotypes and cultural norms maintain gender and sexual inequalities in society. Differential treatment based on gender is also referred to as gender discrimination or sexism and is an inevitable consequence of gender stereotypes. Sexism varies in its level of severity. In parts of the world where women are strongly undervalued, young girls may not be given the same access to nutrition, health care, and education as boys. Further, they will grow up believing they deserve to be treated differently from boys (Thorne, 1993; UNICEF, 2007). Gender stereotypes typically maintain gender inequalities in society. The concept of ambivalent sexism recognizes the complex nature of gender attitudes, in which women are often associated with positive and negative qualities (Glick & Fiske, 2001). It has two components. First, hostile sexism refers to the negative attitudes of women as inferior and incompetent relative to men. Second, benevolent sexism refers to the perception that women need to be protected, supported, and adored by men. There has been considerable empirical support for benevolent sexism, possibly because it is seen as more socially acceptable than hostile sexism.

With regard to sexuality, there is a substantial body of evidence showing that homosexuals and bisexuals are treated differently from heterosexuals in schools, the workplace, and the military. Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes, misinformation, and homophobia (an extreme or irrational aversion to homosexuals). In the United States, significant policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have not been enacted until recently and are primarily the result of local changes rather than national or federal policy.

Reducing Gender Bias and Inequality

Gender inequality based on gender bias is found in varying degrees in most societies around the world, and the United States is no exception. As an individualist culture, North Americans believe people should be free to pursue whatever family and career responsibilities they desire. Still, enculturation and stereotyping combine to limit the ability of girls and boys and women and men alike to imagine less traditional possibilities.

As we learned in earlier lessons, biased attributions lead to negative stereotyping and discrimination, but being aware of your personal biases and situations or contexts where you experience bias helps reduce cultural bias. It is important to remember that biases are not permanent and can be shaped and changed to limit their impact on our thoughts and behaviors (Dasgupta, 2013). In addition to self-awareness, demonstrating empathy (understanding and sharing the feelings of someone else) and taking a culturally relativist perspective is another way to reduce gender bias. When we consider different people’s experiences, we are less likely to make negative and hasty judgments. Challenging and correcting gender stereotypes in everyday activities is another way to reduce gender bias as individuals.

To further reduce gender inequality at a systemic or global level, cultures should work to reduce infant and mother mortality, close gaps in health care and education among girls, and increase employment opportunities and living wages for men and women (World Economic Forum, 2019). Increased enforcement of existing laws against gender-based employment discrimination and sexual harassment will also reduce gender and sexuality-based inequality in the workplace. Globalization and cultural transmission have facilitated improvements in gender inequality, but more can be done to challenge traditional possibilities and increase the opportunities for both females and males.

Educating Children About Gender Norms

Elvin Pederesen-Nielsen discusses the power of education and how having discussions with kids about gender norms can be beneficial to creating an open, safe environment. The challenge of being outside of gender norms is also discussed.

Educating kids about gender norms (open YouTube video in new tab)

As this video discusses, education can play a significant role in dispelling stereotypes and dismantling mechanisms that teach and allow prejudice in society. Classes like this one are designed with that as one of the goals.

Key Takeaways

We often make assumptions about how others should think and behave based on external appearance representing biological characteristics. Still, the process of defining gender and sexuality is complex and includes variations. There are some cultural universals and culturally specific ways of defining masculinity, femininity, and sexuality. Furthermore, variations of sex, gender, and sexual orientation occur naturally throughout the animal kingdom. More than 500 animal species have homosexual or bisexual orientations (Lehrer, 2006). Gender inequality and discrimination are reinforced across cultures and within cultures through stereotypes and misunderstandings, as well as social norms and legal statutes. The traditional binary ways of understanding human differences are insufficient for understanding the complexities of human culture. As gender roles fluctuate, societies will continue to change and adjust.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- Whitehead-link-alternative-sexuality-symbol.svg is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Kinsey_Scale.svg is licensed under a Public Domain license

- art-2101933_1280 © GDJ is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license