9.2 Global Indicators of Health

Health indicators are quantifiable characteristics of a population that researchers use to describe the health of a population. Adopting a standard system with reliable measures for defining health is important for global monitoring of changes in health. Researchers using data collected from around the world look for patterns in identifying, preventing, and treating disease. There are three common global health indicators identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) that directly and indirectly measure and monitor global health:

- Life expectancy

- Infant mortality

- Subjective well-being

Life Expectancy

We are currently living in an aging society (Rowe, 2009). Indeed, by 2030, when the last of the Baby Boomers reach age 65, the U.S. older population will be double that of 2010. Furthermore, because of increases in average life expectancy, each new generation can expect to live longer than their parents’ generation and certainly longer than their grandparents’ generation. As a consequence, it is time for individuals of all ages to rethink their personal life plans and consider prospects for long life. When is the best time to start a family? Will the education gained up to age 20 be sufficient to cope with future technological advances and marketplace needs? What is the right balance between work, family, and leisure throughout life? What’s the best age to retire? How can I age successfully and enjoy life to the fullest when I’m 80 or 90?

Life expectancy is not the same in all parts of the world, however. Differences in access to medical care, clean food and water, public health, and trauma contribute to the great variations in life expectancy throughout the world. Additionally, there are differing definitions of live birth versus stillbirth even among more developed countries, and less developed countries often have poor reporting. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, global life expectancy increased by more than 6 years between 2000 and 2019, from 66.8 years in 2000 to 73.1 years in 2019 (WHO, 2024). While healthy life expectancy (HALE) has also increased by 9% from 58.1 in 2000 to 63.5 in 2019, this was primarily due to declining mortality rather than reduced years lived with disability. In other words, the increase in HALE (5.3 years) has not kept pace with the increase in life expectancy (6.4 years). However, in just two years, the COVID-19 pandemic reversed about a decade of gains in life expectancy at birth. By 2020, both global life expectancy and HALE had rolled back to 2016 levels (72.5 years and 62.8 years, respectively). The following year saw further declines, with both retreating to 2012 levels (71.4 years and 61.9 years, respectively).

Just as young adults differ from one another, older adults are also not all the same. In each decade of adulthood, we observe substantial heterogeneity in cognitive functioning, personality, social relationships, lifestyle, beliefs, and satisfaction with life. Heterogeneity refers to the inter-individual and subgroup differences in level and rate of change over time, and it reflects differences in rates of biogenetic and psychological aging and the sociocultural contexts and history of people’s lives (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Fingerman et al., 2011). Theories of aging describe how these multiple factors interact and change over time. They describe why functioning differs on average between young, middle-aged, young-old, and very old adults and why there is heterogeneity within these age groups.

Life-course theories highlight the effects of social expectations and the normative timing of life events and social roles (e.g., becoming a parent, retirement). They also consider the lifelong cumulative effects of membership in specific cohorts (generations) and sociocultural subgroups (e.g., race, gender, socioeconomic status) and exposure to historical events (e.g., war, revolution, natural disasters; Elder et al., 2003; Settersten, 2005).

Lifespan theories complement the life-course perspective with a greater focus on processes within the individual (e.g., the aging brain). This approach emphasizes the patterning of lifelong intra- and inter-individual differences in the shape (gain, maintenance, loss), level, and rate of change (Baltes, 1987, 1997). Both life-course and lifespan researchers generally rely on longitudinal studies to examine hypotheses about different patterns of aging associated with the effects of biogenetic, life history, social, and personal factors.

Cross-sectional studies provide information about age-group differences, but these are confounded with cohort, time of study, and historical effects.

Infant Mortality

In peripheral nations with low per capita income, it is not the cost of healthcare that is the most pressing concern. Rather, low-income countries must manage such problems as infectious disease, high infant mortality rates, scarce medical personnel, and inadequate water and sewer systems. Such issues, which high-income countries rarely even think about, are central to the lives of most people in low-income nations. Due to such health concerns, low-income nations have higher rates of infant mortality and lower average life spans. UNICEF estimates that in 2021, the global under-five mortality rate was 38 deaths per 1,000 live births.

One of the biggest contributors to medical issues in low-income countries is the lack of access to clean water and basic sanitation resources. While access to safe drinking water and sanitation has improved, billions still lack these basic necessities. According to the World Bank (May 2024), over 2 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, and 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation facilities.

The U.S. Infant Mortality Crisis

According to the Centers for Disease Control, “over 20,500 infants died in the United States in 2022. The five leading causes of infant death in 2022 were: birth defects, preterm birth and low birth weight, maternal pregnancy complications, sudden infant death syndrome, and unintentional injuries (e.g., suffocation). Unfortunately, in the United States, babies born to black mothers died at a rate of 10.9 per 1,000 births—more than twice the rate for white, Asian, or Hispanic women. So, while infant mortality rates have fallen overall across the US, the black-white disparity is still present. Understanding why black babies die at more than twice the rate of other babies means we have to examine the role that racism plays in our society.

Obeng et al. (2024) note that the leading causes of Black infant mortality in the US are “low birthweight, congenital malformations, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), accidental/unintentional injuries, and maternal complications. Some additional risk factors related to the mothers for increased IMR are obesity, smoking, not receiving Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits, receiving late or no postnatal care, and having Medicaid compared to private insurance.”

Tribal communities in the US are also disproportionately affected by infant mortality. A recent study (Thyden, 2024) found that the high infant mortality rate among Native American and Alaska Native infants is exacerbated by inadequate investigations into sudden unexpected infant deaths, often conducted by law enforcement rather than medical examiners, leading to a lack of critical data for prevention efforts. Many rural native communities have strained relationships with law enforcement, and additionally, police may not ask caregivers to show the position in which the deceased infant was found. These reenactments help investigators determine if poor housing and sleeping conditions are factors in these deaths. Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of the Urban Indian Health Institute, suggests that there is a need for birthing clinics that offer reproductive care, lactation education, and support groups that understand tribal cultural practices (Hassanein, 2024).

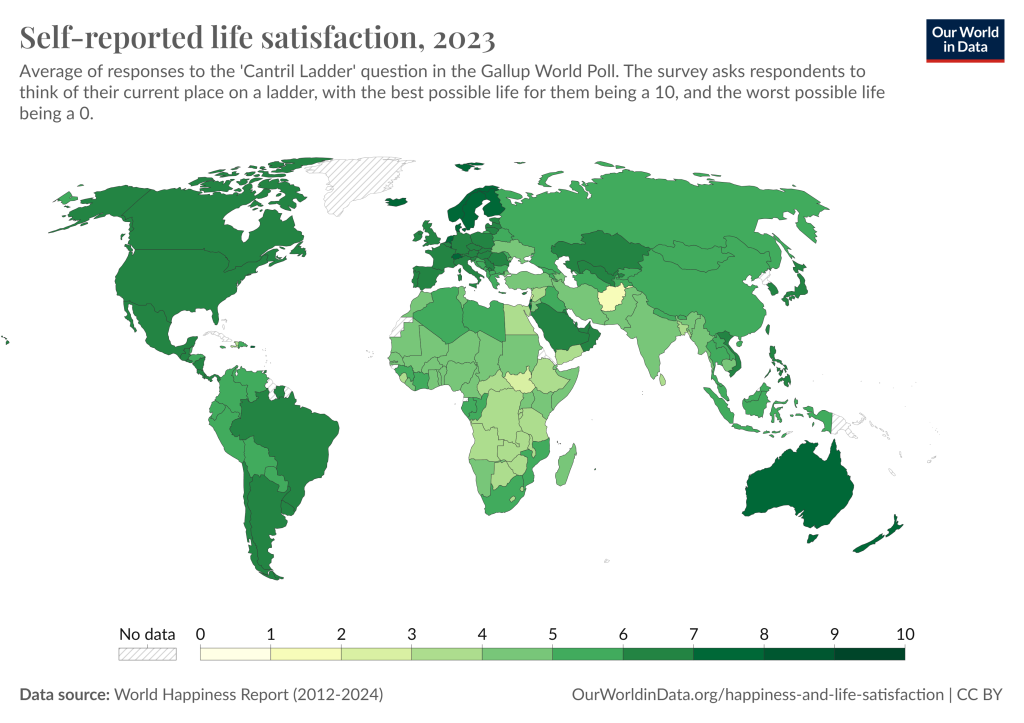

Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being (SWB) is the scientific term for happiness and life satisfaction, thinking and feeling that your life is going well, rather than badly. Levels of subjective well-being are influenced by both internal factors, such as personality and outlook, and external factors, such as the society in which a person lives. Some of the major determinants of SWB are a person’s inborn temperament, the quality of their social relationships, the societies they live in, and their ability to meet their basic needs. Although there are additional forms of SWB, the three in the table below have been studied extensively. The table also shows that the causes of the different types of happiness can be somewhat different.

| Three Types of Happiness | Examples | Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction |

|

|

| Positive feelings |

|

|

| Low negative feelings |

|

|

As you can see in the table above, there are different causes of happiness, and these causes are not identical for the various types of SWB. High SWB is achieved by combining several different important elements (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2008). People who promise to know the key to happiness are oversimplifying. Some people experience all three elements of happiness and are very satisfied, enjoy life, and have only a few worries or other unpleasant emotions. Other unfortunate people are missing all three. For example, imagine an elderly person who is completely satisfied with her life—she has done most everything she ever wanted—but is not currently enjoying life that much because of the infirmities of age. There are others who show a different pattern who are having fun, but who are dissatisfied and believe they are wasting their lives.

Societal Influences on Happiness

When people consider their own happiness, they tend to think of their relationships, successes and failures, and other personal factors. But a very important influence on how happy people are is the society in which they live. It is easy to forget how important societies and neighborhoods are to people’s happiness or unhappiness.

Is the state of happiness truly a good thing? Is happiness simply a feel-good state that leaves us unmotivated and ignorant of the world’s problems? Should people strive to be happy, or are they better off to be grumpy but “realistic”? Some have argued that happiness is actually a bad thing, leaving us superficial and uncaring. Most of the evidence so far suggests that happy people are healthier, more sociable, more productive, and better citizens (Diener & Tay, 2012; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). Research shows that the happiest individuals are usually very sociable. The table below summarizes some of the major findings. In other words, people high in SWB seem to be healthier and function more effectively compared to people who are chronically stressed, depressed, or angry. Happiness does not just feel good in the moment, but it is good for people over time and for those around them.

| Positive outcomes | Description of some of the benefits |

|---|---|

| Health and longevity | Happy and optimistic people have stronger immune systems and fewer cardiovascular diseases. Happy people are more likely to perform healthy behaviors, such as wearing seat belts and adhering to medical regimes. They also seem, on average, to live longer. |

| Social relationships | Happy people are more popular, and their relationships are more stable and rewarding. For example, they get divorced less and are fired from work less. They support others more, and receive more support from others in return. |

| Productivity | Organizations in which people are positive and satisfied seem to be more successful. Work units with greater subjective well-being are more productive, and companies with happy workers tend to earn more money and develop higher stock prices. |

| Citizenship | Happy people are more likely to donate their time and money to charitable causes and to help others at work. |

Money and Happiness

A certain level of income is needed to meet our needs, and very poor people are frequently dissatisfied with life (Diener & Seligman, 2004); however, having more and more money has diminishing returns. This means that higher and higher incomes make less and less difference to happiness. Wealthy nations tend to have higher average life satisfaction than poor nations, but the United States has not experienced a rise in life satisfaction over the past decades, even as income has doubled. The goal is to find a level of income that you can live with and earn.

It is important to always keep in mind that high materialism seems to lower life satisfaction—valuing money over other things, such as relationships, can make us dissatisfied. When people think money is more important than everything else, they seem to have a harder time being happy. And unless they make a great deal of money, they are not, on average, as happy as others. Perhaps in seeking money, they sacrifice other important things too much, such as relationships, spirituality, or following their interests. Or it may be that materialists just can never get enough money to fulfill their dreams—they always want more.

Self-Examination

Although it is beneficial generally to be happy and satisfied, this does not mean that people should be in a constant state of euphoria. In fact, it is appropriate and helpful sometimes to be sad or to worry. At times, a bit of worry mixed with positive feelings makes people more creative. Most successful people in the workplace seem to be those who are mostly positive but sometimes a bit negative. You do not need to be a happiness superstar in order to be a superstar in life. What is not helpful is to be chronically unhappy. If you feel mostly positive and satisfied, and yet occasionally worry and feel stressed, this is probably fine as long as you feel comfortable with this level of happiness. If you are a person who is chronically unhappy much of the time, changes are needed, which may include some professional support.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- 291476988.jpg © RIBI is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- happiness-cantril-ladder © OurWorldinData.org is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- image-8fe54c0b-92da-4b19-9b2c-053faf3bb692 © streetwindy is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license