9.3 Health in American Culture

“Our bodies are our gardens, our wills are our gardeners.” William Shakespeare

Given that the United States spends more on health care than most (if not all) industrialized nations in the world, one could reasonably expect the American people to be some of the healthiest citizens in the world. How is it then that modern Americans are significantly less healthy than other societies and may even be expected to live shorter lives than previous generations? In this module, aspects of Western culture will be viewed through the lens of their impact on our physical health, including our perceptions of health, desire to be healthy, and access to health education and resources. Here we will explore the impact of American culture on four aspects of health.

American Diet

Numerous studies have attempted to identify contributing factors for poor health habits in the United States that have contributed to rising rates of obesity and diseases related to obesity. These studies have resulted in numerous hypotheses as to what those key factors are. A common theme is that of too much food, too little exercise, and a sedentary schedule; however, these themes are increasingly viewed as overly simplistic and lacking in awareness of the complex approaches that are needed to improve healthy living for all Americans. For example, while dieting, people tend to consume more low-fat or fat-free products, even though those items can be just as damaging to the body as those with fat. According to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), more than 80% of Americans have dietary patterns low in vegetables, fruits, and dairy.

Other factors not directly related to caloric intake and activity levels are also believed to contribute to lowered physical fitness and higher body mass index (BMI) rates. These include careers that involve long hours of sitting, decreased ability to delay gratification, and heavy marketing to promote unhealthy foods. Genetics are also believed to be a factor that contributes to higher BMI. In a 2018 study at Tufts University, researchers stated that the presence of the human gene APOA2 could result in a higher BMI in individuals. Also, the probability of obesity can even start before birth due to things that the mother does, such as smoking and gaining a lot of weight. Among the complex factors impacting eating habits in American culture are two key enculturated trends:

- Consumer culture

- Mixed media messaging

Consumer culture focuses on the spending of the customer’s money on material goods to attain a lifestyle in a capitalist economy. Over the years, people of different age groups have been employed by marketing companies to help understand the beliefs, attitudes, values, and past behaviors of the targeted consumers. As consumers grow increasingly removed from food production, the role of product creation, advertising, and publicity becomes the primary vehicles for information about food. With processed food as the dominant category, marketers have almost infinite possibilities in developing their products for mass appeal.

Today’s American citizens are inundated with marketing messages that food choices should be fast, bring us pleasure, and meet our emotional needs over physiological needs. Of the food advertised to children on television, 73% is fast or convenience foods (Kunkel, 2009). Additionally, Americans are often enculturated to pursue personal satisfaction while also adhering to unrealistic standards of fitness and attractiveness. Our consumer culture promotes these conflicting standards with mixed media messaging in various formats.

Movement

Due to much of what has been discussed in this module regarding marketing, the abundant availability of calorie-dense foods, the increase of sedentary jobs, and technological advances, obesity in the U.S. is on the upswing.

Some schools are trying to mitigate these things by starting early and creating inspiring projects to impart movement culture to their students. Exercise can be physiologically beneficial to the human body and has similar beneficial impacts as medicine. Of course, if an individual is suffering from a diagnosable medical condition, it is recommended that they work with a credentialed treatment provider and receive proper clearance to start an exercise program. Whether an individual has a medical condition or not, the discussion about the medical and physiological benefits of exercise is important, and the literature continues to support it.

On a governmental level, the Surgeon General has made a call to action for Americans to include regular movement practice in their lives and has also put out data and details regarding its benefits. Read the Surgeon General’s call to action here: Executive Summary from Step It Up!: Surgeon General’s Call to Action [New Tab].

The Centers for Disease Control is also on board and has put out several pieces of information and statistics: Physical Activity Basics [New Tab]

Movement and Dance

While there are many other creative ways to create healthy movement habits, due to the scope of this course, we will focus on dance. There are formal fitness programs such as Salsa Aerobics, Zumba, and BollyX, and there is simply dancing for joy, during social gatherings, and celebrations such as weddings and graduations.

Dance itself has had several historical evolutions and iterations over the years. There is slow dance, tap, jazz, swing, line, hip hop, and ballroom. Eastern influences have also been embraced in the U.S., such as belly dancing. There is the martial art style of capoeira that hails from Brazil, blending dance with combat and performance. There are many creative ways to impart healthy movement in an enjoyable manner into daily life. While there are formal ways to incorporate dance and movement into an active lifestyle, there is also the simple enjoyment of dance. Culturally, people will dance for joy during social gatherings and celebrations such as weddings and graduations.

Sleep Hygiene

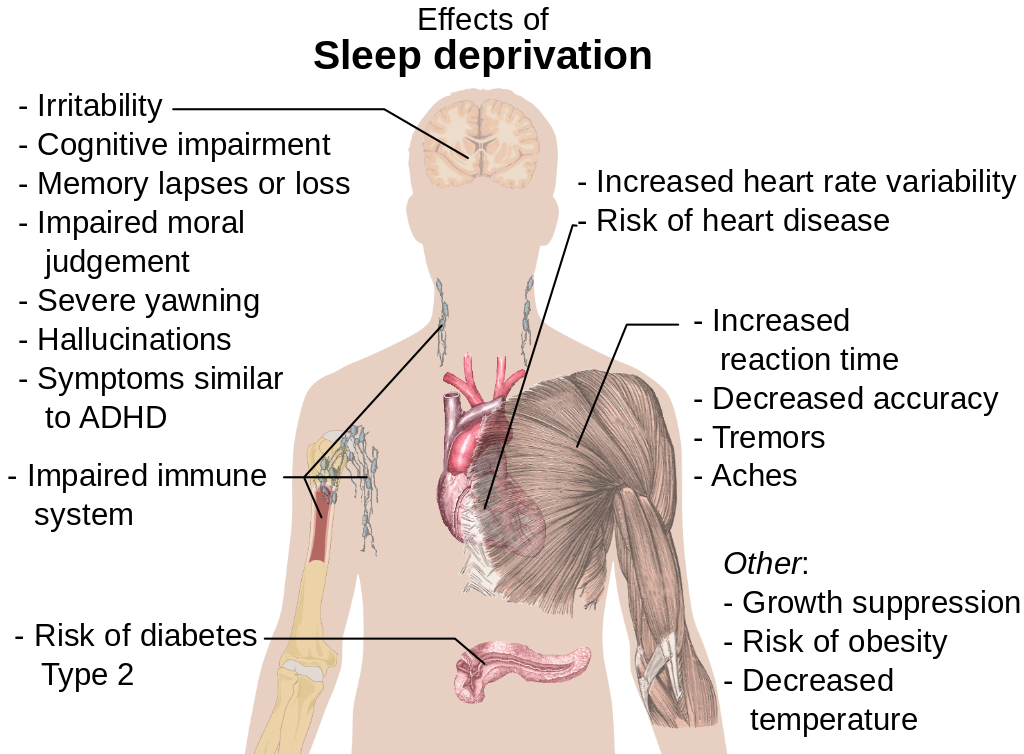

Along with food and water, sleep is one of the human body’s most important physiological needs—we cannot live without it. Extended sleeplessness (i.e., lack of sleep for longer than a few days) has severe psychological and physical effects. Research on rats has found that a week of no sleep leads to loss of immune function, and two weeks of no sleep leads to death.

Despite its clear importance to psychological and physiological functioning, researchers have struggled for centuries to answer the question of why we sleep. On the surface, we know that sleep helps our body recuperate from a day’s physical exertions. It also aids in recovery from illnesses and infections. We also know that extended sleeplessness can lead to hallucinations, delusions, loss of immune function, and in extreme cases, death. Modern research has also uncovered that sleep has a major role in maintaining our mental and emotional health.

Though scientists are still learning about the concept of basal sleep need (just how much sleep we need), research has demonstrated that sleeping too little can inhibit your productivity and your ability to remember and consolidate information. Lack of sleep can also lead to serious health consequences, jeopardizing individual safety and the safety of others.

For example, sleep deprivation is related to:

- Higher rates of motor vehicle accidents;

- Higher BMI, an increased likelihood of obesity, and increased risk of diabetes and heart problems;

- Higher risk for depression and substance abuse;

- Decreased attention, slower reaction times, and the inability to remember new information.

When we do not sleep enough, we accumulate a sleep debt. Sleep debt occurs as the result of not getting enough sleep, and a large debt causes mental, emotional, and physical fatigue. Sleep debt results in diminished abilities to perform high-level cognitive functions.

According to a 2023 Gallup poll, only 26% of Americans report getting eight or more hours of sleep. The United States experiences some of the highest rates of sleep deprivation and sleep disorders in the industrialized world; it is worth examining aspects of American culture that contribute to this trend.

Researchers examining health trends in the United States have highlighted our time-sensitive culture, emphasis on technology, and general attitudes toward sleep as contributing factors to our sleep hygiene. The average worker worked 1,868 hours in 2007, an increase of 181 hours from the 1979 work year of 1,687 hours (Mishel et al., 2012). Overall, the United States labor force is one of the most productive in the world, largely due to its workers working more than those in any other post-industrial country (excluding South Korea). Americans generally hold working and being productive in high regard. Being busy and working extensively is a source of pride for many and, as they say in America, “time is money.”

Additionally, while there is little dispute that technology has enhanced our daily lives, studies show it is also negatively impacting our sleep habits. The increased stimulation of our devices can make it more difficult to unwind at the end of the night, while the unique light put off by these devices also blocks key sleep hormones. The National Sleep Foundation convened a panel of experts (2025), who found that screen use and the content viewed on screens disrupts the sleep health of both children and teens

Overall health is correlated with the quantity and quality of our sleep. Studies have shown that those who engaged in protective habits (e.g., getting 7–8 hours of sleep regularly, not smoking or drinking excessively, exercising) had fewer illnesses, felt better, and were less likely to die over a 9-12-year follow-up period (Belloc & Breslow 1972; Breslow & Enstrom 1980). For college students, health behaviors can even influence academic performance. Poor sleep quality and quantity are related to weaker learning capacity and academic performance (Curcio et al., 2006). Overall, people who sleep less are more likely to be obese, report higher levels of stress, and/or report symptoms of a mood disorder than those who obtain optimal levels of sleep each night (CDC, 2014).

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Social class in the United States is a controversial issue, with social scientists disagreeing over models, definitions, and even the basic question of whether or not distinct classes exist. Many Americans believe in a simple three-class model that includes the rich or upper class, the middle class, and the poor or working class. More complex models that have been proposed by social scientists describe as many as a dozen class levels. Regardless of which model of social classes is used, it is clear that socioeconomic status (SES) is tied to particular opportunities and resources. SES refers to a person’s position in the social hierarchy and is determined by their income, wealth, occupational prestige, and educational attainment. Most definitions of the social classes in the United States, however, entirely ignore the existence of parallel black, Hispanic, and other non-white communities.

While social class may be an amorphous and diffuse concept, with scholars disagreeing over its definition, tangible advantages are associated with high socioeconomic status. People in the highest SES bracket, generally referred to as the upper class, likely have better access to healthcare, marry people of higher social status, attend more prestigious schools, and are more influential in politics than people in the middle class or working class. People in the upper class are members of elite social networks, effectively meaning that they have access to people in powerful positions who have specialized knowledge. These social networks confer benefits ranging from advantages in seeking education and employment to leniency by police and the courts. Sociologists may dispute exactly how to model the distinctions between socioeconomic statuses, but the higher up the class hierarchy one is in America, the better health, educational, and professional outcomes one is likely to have.

Education in higher socioeconomic families is typically stressed as more important, both within the household and the local community. In poorer areas, where food, shelter, and safety take priority, education often takes a backseat and becomes less of a priority. American youth are particularly at risk for many health and social problems in the United States. Overall, lower socioeconomic status has been linked to chronic stress, heart disease, ulcers, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, certain types of cancer, and premature aging.

SES differences in health have long been associated by many Americans as related to poor impulse control, unhealthy habits, and an overall lack of motivation (Braveman et al., 2010). One difficulty with this oversimplification is that these attitudes reduce poverty (and related problems associated with lower SES) as a problem with the individual rather than a reflection of complex societal components that contribute to poor health and lower life expectancy. The assumption that individual choices and internal control are enough to overcome the impact of poverty further adds to the difficulty impoverished people have in overcoming economic hardships. Educational, economic, and health care inequity within lower SES groups have each been shown to correlate with poor health must be addressed in order to create meaningful change in the health of Americans (Braveman et al., 2010). Given the ranking of the United States across global indicators, we might do well to address the poor health of Americans as a social problem and not a personal problem.

Ethnic/Racial Disparity (SES)

The Role of Race in Health in the U.S.

Health disparities refer to gaps in the quality of health and healthcare across racial and ethnic groups. Race and health research, often done in the United States, has found both current and historical racial differences in the frequency, treatments, and availability of treatments for several diseases. This can add up to significant group differences in variables such as life expectancy. Many explanations for such differences have been argued, including socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, social environment, and access to preventive health-care services, among other environmental differences.

In multiracial societies such as the United States, racial groups differ greatly in regard to social and cultural factors such as socioeconomic status, healthcare, diet, and education. There is also the presence of racism, which some see as a very important explanatory factor. Some argue that for many diseases, racial differences would disappear if all environmental factors could be controlled. Race-based medicine is the term for medicines that are targeted at specific ethnic clusters, which are shown to have a propensity for a certain disorder. Critics are concerned that the trend of research on race-specific pharmaceutical treatments will result in inequitable access to pharmaceutical innovation, and smaller minority groups may be ignored.

Health disparities based on race also exist. Similar to the difference in life expectancy found between the rich and the poor, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (2021), white women live about 10 years longer in the U.S. (80.4 years) than black men (70.8 years). There is also evidence that blacks receive less aggressive medical care than whites, similar to what happens with women compared to men. Black men describe their visits to doctors as stressful and report that physicians do not provide them with adequate information to implement the recommendations they are given.

Another contributor to the overall worse health of blacks is the incidence of HIV/AIDS; the rate of new AIDS cases is ten times higher among blacks than whites, and blacks are 20 times as likely to have HIV/AIDS as are whites. Health disparities are well documented in minority populations such as African Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos. When compared to European Americans, these minority groups have a higher incidence of chronic diseases, higher mortality, and poorer health outcomes.

World-ranked tennis professional Serena Williams developed a blood clot in her lung after giving birth to her daughter.

Minorities also have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS, and infant mortality than whites. American ethnic groups can exhibit substantial average differences in disease incidence, disease severity, disease progression, and response to treatment.

Minority populations have increased exposure to environmental hazards that include a lack of neighborhood resources, structural and community factors, as well as residential segregation that result in a cycle of disease and stress (Gee, 2004). Racial segregation is another environmental factor that occurs through the discriminatory action of those organizations and working individuals within the real estate industry, whether in the housing market or rentals. Even though residential segregation is noted in all minority groups, blacks tend to be segregated regardless of income level when compared to Latinos and Asians. Thus, segregation results in minorities clustering in poor neighborhoods that have limited employment, medical care, and educational resources, which is associated with high rates of criminal behavior (Williams, 2005). In addition, segregation affects the health of individual residents because the environment is not conducive to physical exercise due to unsafe neighborhoods that lack recreational facilities and have nonexistent recreational space.

Racial and ethnic discrimination adds an additional element to the environment that individuals have to interact with daily. Individuals who report discrimination have been shown to have an increased risk of hypertension in addition to other physiological stress-related effects (Mujahid, 2011). The high magnitude of environmental, structural, and socioeconomic stressors leads to further compromise of the psychological and physical being, which leads to poor health and disease (Gee, 2004).

There is a controversy regarding race as a method for classifying humans. The continued use of racial categories has been criticized. Apart from the general controversy regarding race, some argue that the continued use of racial categories in health care and as risk factors could result in increased stereotyping and discrimination in society and health services. There is general agreement that a goal of health-related genetics should be to move past the weak surrogate relationships of racial health disparity and get to the root causes of health and disease. This includes research that strives to analyze human genetic variation in smaller groups across the world.

Health Equity- Changing Systems Not Victims | Dr. Alvin Powell | TEDxRaleigh (open YouTube video in new tab)

Global Health Cross-Cultural Comparisons

Many of the factors explored in American health also relate to global health, such as:

- Access to health education and care

- Socioeconomic and racial disparities

- Food or housing scarcity

Health disparities are also due in part to cultural factors that involve practices based not only on sex, but also gender status. For example, in China, health disparities have distinguished medical treatment for men and women due to the cultural phenomenon of preference for male children. Additionally, a girl’s chances of survival are impacted by the presence of a male sibling. Girls do have the same chance of survival as boys if they are the oldest girl, but they have a higher probability of being aborted or dying young if they have an older sister.

In India, SES and gender-based health inequities are apparent in early childhood. Many families provide better nutrition for boys in the interest of maximizing future productivity, given that boys are generally seen as breadwinners. In addition, boys receive better care than girls and are hospitalized at a greater rate. The magnitude of these disparities increases with the severity of poverty in a given population.

Additionally, the cultural practice of female genital mutilation (FGM) is known to impact women’s health, though it is difficult to know the worldwide extent of this practice. FGM, also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is the ritual cutting or removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. While generally thought of as a Sub-Saharan African practice, it may have roots in the Middle East as well. The estimated 3 million girls who are subjected to FGM each year potentially suffer both immediate and lifelong negative effects. Long-term consequences include urinary tract infections, bacterial vaginosis, pain during intercourse, and difficulties in childbirth that include prolonged labor, vaginal tears, and excessive bleeding (“Female Genital Mutilation”, 2019).

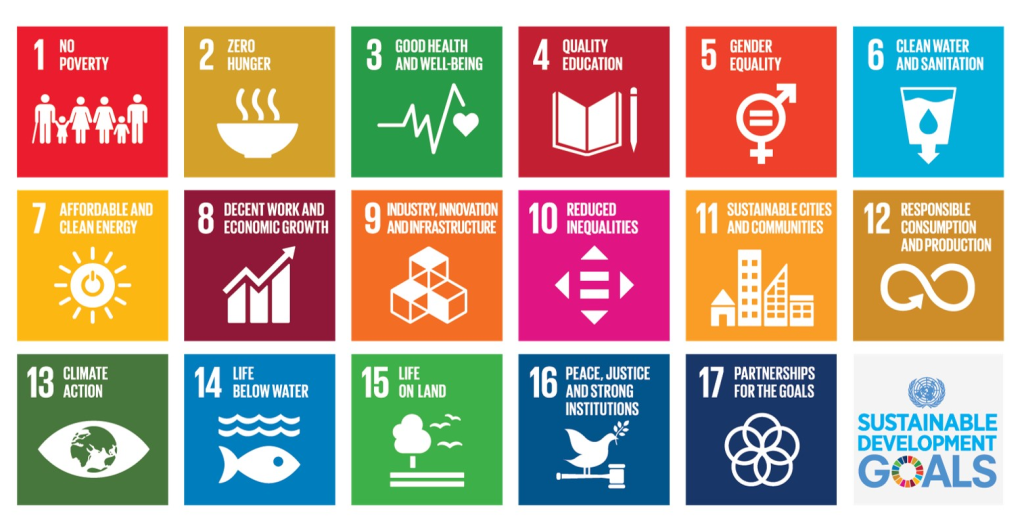

Globally, the poorest countries in the world remain the least healthy (CDC, 2013). In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) released “Key Facts” regarding human rights and health, which identified the need for multiple countries to unify in targeting health disparities and basic rights/needs. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a collection of 17 global goals set by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in 2015 for the year 2030. According to the United Nations, the long-term target is to reach the communities farthest behind and most in need.

There are 169 targets for the 17 goals shown above. Each target has between one and three indicators used to measure progress toward reaching the targets. The UN Development Reports (2023) state that 824–991 million of the 1.1 billion poor people lack adequate sanitation, housing, or cooking fuel. More than half of poor people are deprived of nutrition, electricity, or years of schooling. Almost 80 percent of poor people who lack access to electricity—444 million—live in Sub-Saharan Africa and are being left behind in an increasingly digital world.

There are many obstacles to realizing this global call to end human suffering, improve the environment, and ensure access to basic needs. Critics of SDGs highlight the high cost of achieving even the initial target goals and suggest the plan is overly complex. Currently, world leaders continue to work with the United Nations in pursuit of global peace and prosperity to improve human health and well-being.

Key Takeaways

There is considerable cultural variation in what it means to be healthy. The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a widely adopted definition of health to include a biopsychosocial approach to well-being. For many, the identification of health versus illness often depends on subjective labeling of how a person feels in the moment, but in reality, overall health is determined by a complex set of variables.

There is a great deal of intracultural variability in the United States when it comes to health and well-being. In particular, disparity exists in groups based on socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity when it comes to access to health resources and care. Additionally, enculturated experiences, perceptions, and values further influence American health in regard to diet and sleep hygiene. The future of health in the United States and globally will be shaped by the ability of future generations to tackle the complex challenges faced within each culture.

Test your understanding

Media Attributions

- pexels-rollz-19971194 © Rollz International is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Wedding_Dance_Ceremony © Dinesh Mendhe is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- image-df32a442-5e2c-44f4-86ae-1e7b5c108bbc © Mikael Häggström is licensed under a Public Domain license

- image-df7d2079-affe-4876-8f9e-40febd70026b © Gina Hughes is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- image-9ab86570-dc28-4d10-9e7f-daf4da859cad © United Nations is licensed under a Public Domain license